Abstract

Competence-questioning communication at work has been described as gender-linked (e.g., mansplaining) and as impacting the way women perceive and experience the workplace. Three studies were conducted to investigate how the specific communication behaviors of condescending explanation (i.e., mansplaining), voice nonrecognition, and interruption can be viewed as gender-biased in intention by receivers. The first study was a critical incident survey to describe these competence-questioning behaviors when enacted by men toward women in the workplace and how women react toward them. Studies 2 and 3 used experimental paradigms (in online and laboratory settings, respectively) to investigate how women and men perceive and react to these behaviors when enacted by different genders. Results demonstrated that when faced with condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, or interruption, women reacted more negatively and were more likely to see the behavior as indicative of gender bias when the communicator was a man. Implications for improving workplace communications and addressing potential gender biases in communication in organizations are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

“The men in charge of running the meeting that day didn’t acknowledge what I said…and made a big show of looking up the information we needed on the internet in the middle of the meeting. I felt embarrassed that I was ignored and overlooked, and angry when it turned out that my information would have been right.” - quote from a woman participant in Study 1 describing an incident of voice nonrecognition

Stereotypes of women as less competent (e.g., Biernat & Kobrynowicz, 1997; Hebl et al., 2008) may lead others to downgrade, ignore, and question the importance of their contributions. These challenges to women’s full participation at work have become increasingly described in public discourse as the difficulties of “speaking while female” (Sandberg & Grant, 2015) due to behaviors like being interrupted and lack of acknowledgement when voicing suggestions. Such competence-questioning communication behaviors have been portrayed in the popular press as sexist, with various neologisms such as “mansplaining” (a man explains to a woman something she knows more about than he does; McNamara, 2017; Solnit, 2014) and “manterrupting” (a man interrupts a woman when she is speaking; Bennett, 2015).

Of highest prominence is “mansplaining.” Bridges (2017) dissects the term as metapragmatics (“speech about what language is doing in a particular context,” p. 96) and discusses how it contributes to discourse on women’s experiences, gender equality, and institutional sexism. Indeed, “mansplaining” is now prolific on news and social media platforms. From Twitter, Lutzky and Lawson (2019) collected over 17,000 tweets and retweets containing #mansplaining in a span of 6 months in 2016 to 2017. Underscoring the potential harm of the behavior, Dular (2021) writes that mansplaining is a “dysfunctional subversion of the epistemic roles of speaker and hearer” (p. 9)—that is, the hearer of knowledge (i.e., the man) forcefully reverses the role of speaker and hearer, silencing the true speaker and precluding them as a giver of knowledge (i.e., the woman). Still, there is relatively little research on why and how the behavior occurs, as well as reactions to it.

We investigate “mansplaining” and related behaviors here, and subsequently contribute to theory and research on gender at work in several ways. First, we draw upon Status Characteristics Theory (SCT; Berger et al., 1977) which explicates why gender may be related to ascribed status at work. Specifically, we examine behaviors linked to questioning, doubting, or downgrading another’s competence, evaluating whether these behaviors are perceived as linked to gender and viewed differently depending upon who engages in them. While gender is not dichotomous, in this paper, we focus on men and women as the two most common identity groups. Second, we expand on the Power as Control model (PAC; Goodwin et al., 2000) and the Shifting Standards Model (Biernat & Fuegen, 2001; Biernat et al., 2010) by naming and investigating specific, competence-questioning behaviors these models suggest occur, but that have heretofore been uninvestigated. Further, our research has the potential to directly contribute to practice in that competence-questioning behaviors may have a significant impact on employee self-efficacy and work attitudes. Research has demonstrated that lower self-efficacy will negatively impact engagement, job satisfaction, and job performance (Judge & Bono, 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

To address these aims, we define competence-questioning communication behaviors and provide theoretical rationale regarding their greater enactment by men toward women. We present critical workplace incidents to delineate greater context for these interactions, and examine women’s emotional, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to these competence-questioning behaviors by assessing feelings, attributions, and behaviors of women who have experienced such communication directed toward them. We then use an experimental paradigm in two studies to assess whether differences in perceptions and affective responses to competence-questioning behavior are dependent on the gender of the recipient, while also considering the gender of the communicator. In the following sections, we briefly review the small bodies of literature associated with whether these behaviors are gender-linked, followed by the description of three studies aimed at further understanding these behaviors and the reactions they elicit.

Competence-Questioning Communication Behaviors

In day-to-day workplace conversations, individuals may address another’s performance while executing various tasks (e.g., making a correction to something that was said or done, suggesting a better way of doing something). Such feedback behavior contributes to workplace productivity and can be helpful to individual skill development and efficacy (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). However, some forms of communication can imply that one’s competence is in doubt or directly challenge that one is competent. We define competence-questioning communication behaviors as those communication actions that indicate one doubts, questions, or challenges another’s competence. We derived this concept of competence-questioning from theory on how power and status can lead to differential treatment and different standards at work (SCT, Berger et al., 1977; PAC, Goodwin et al., 2000; Shifting Standards Model, Biernat et al., 2010).

Before discussing these theoretical frameworks, it is useful to note how competence-questioning behaviors fit into broader literature on workplace incivility and microaggressions. Microaggressions have been defined as indignities communicating racial slights and insults; hence, the literature focuses on race not gender, and few studies have attempted to expand the concept to gender (Costa et al., 2022; Lui & Quezada, 2019). However, definitionally, one might see competence-questioning behaviors as exemplars of microinsults and microinvalidations (Sue et al., 2007). Note that the microaggressions literature has been heavily critiqued because of the definitional confounding of behavior and attribution (e.g., Lilienfeld, 2020; Mekawi & Todd, 2021; Spanierman et al., 2021); one of the primary aims of our studies is to disentangle these by separating the attribution to sexism (inherent in the term mansplaining) from the behavior of questioning competence itself. That is, a questioning of another’s competence can be motivated by many reasons (e.g., a concern for quality of the work, a desire to provide helpful advice); confounding attribution and behavior does not allow for an accurate evaluation of when such behaviors may be rooted in sexism and when they are seen as due to other factors. Further, Lui et al. (2020) noted that consideration of deliverer intent was key to how discriminatory various forms of microaggressions were viewed, and Mekawi and Todd (2021) advocated for microaggression research to look at events independent of intention and impact as necessary given the misunderstanding and minimization of this research stream. In addition to a conceptual distinction, our work also focuses on the behavior- or episode-level, rather than an aggregation across time, contexts, and sources, as is the typical approach in the microaggressions literature. This further allows us to address critiques of the microaggression literature as being insufficiently clear about different types of events that fit within an umbrella construct (Lui et al., 2020; Mekawi & Todd, 2021), as well as allowing us to consider specific actor variables as influencing perceptions (i.e., actor gender).

Competence-Questioning as Sexism

SCT (Berger et al., 1977) posits that one’s categorization into a social group will signal one’s ascribed status in a workgroup. Status characteristics are categorized as more or less socially desirable, and those that are more desirable signal status and competence for individuals who possess them. For much of modern history, men have been ascribed greater status and competence than women (Bruckmüller et al., 2014; Eagly & Karau, 2002). Although recent research by Eagly and colleagues (Eagly et al., 2019) suggests gender stereotypes have shifted over the years and women are no longer seen as less competent than men among US adults, stereotypical perceptions regarding women as less agentic persist (Eagly et al., 2019) and women do not attain high-status positions at the same rate as men. Position, pay, and evaluation differences are likely to continue to fuel gender as a status characteristic (e.g., Heilman et al., 2019; PayScale, 2019; Warner et al., 2018).

SCT falls under the umbrella of expectation states theories, meaning that the characteristics an individual possesses not only affect observers’ perceptions of status, but also how individuals themselves behave because of expectations that are created (Berger et al., 1977; Wagner & Berger, 1997). Berger and colleagues (Berger et al., 1977; Wagner et al., 1997) state that these expectations result in hierarchies within groups, such that those possessing characteristics labeled as high status (i.e., creating expectations for high performance) find themselves at the top of the hierarchy, while those possessing characteristics labeled as low status are pushed to the bottom. We first discuss how status expectations may lead members of the social group with higher ascribed status (men) to question the competence of those in the social group with lower ascribed status (women). We follow this with a discussion of how SCT suggests the lower status group (women) might interpret such behaviors.

Competence-Questioning Behavior by Men

Competence-questioning behaviors may be a manifestation of bias by those with higher ascribed status. The PAC model (Goodwin et al., 2000) suggests those in power attend more to stereotype consistent information and ignore individuating information. The model suggests that this occurs both by default (i.e., those in power are too busy, too self-focused) and by design (e.g., to justify one’s superior position). While the model is focused on the biasing effects of power in supervisor-subordinate relationships, it indicates that those in societally privileged positions (i.e., men) might ignore or downplay competence displays by those of lower status (i.e., women). Additionally, research on the Shifting Standards Model (Biernat & Fuegen, 2001; Biernat et al., 2010) indicates that suspicion of incompetence is triggered more quickly when there exists a stereotype about competence. That is, women who display a behavior that is counter-stereotypic (i.e., competent), are likely to have their behavior questioned, downplayed, or penalized. This is supported by research indicating penalties for mistakes (i.e., incompetent actions) are greater for women behaving counter-stereotypically (such as being agentic in voicing thoughts, taking actions, etc.), as well as research showing recognition of improved performance (i.e., competent actions) is less for women than men (Brescoll et al., 2010; Heilman et al., 2019). Doubting, questioning, or challenging competence can be a way of “pushing back” against a display of competence. Blair-Loy et al. (2017) labeled this the “prove it again” bias associated with shifting standards for women.

Note that the questioning of competence may not be limited to being reactive as positioned in this research on penalties, recognitions, and judgments of women’s performance; we would argue that the pervasiveness of stereotypes regarding women and competence (Fiske et al., 2002) can mean that competence is questioned or doubted before it is even displayed. That is, we see competence-questioning behaviors as deriving from both penalty (i.e., penalized for displaying competence) and deficiency (i.e., viewed as lacking competence) biases on the part of the questioner (i.e., men), in line with the work of Smith et al. (2019) on leadership performance evaluations of women.

Interpretation of Competence-Questioning Behavior by Women

SCT also can explain why a competence-questioning behavior might be interpreted as a gendered phenomenon (i.e., attributed to bias against one’s gender). Under SCT, status characteristics can be activated by a diffuse characteristic like gender (i.e., different levels of competence are associated with different genders historically), such that an individual in a workgroup will become aware of certain expectations for both their and others’ performance based on that characteristic (Berger et al., 1977; Wagner et al., 1997). On the part of the receiver of a competence-questioning behavior (particularly when that behavior is more of a subtle than direct question of competence), the behavior alerts the receiver to the social expectations stemming from salient status characteristics, such as gender. Thus, we expect those women on the receiving end of a competence-questioning behavior by someone different-gender (e.g., men) will be more likely to have negative reactions compared to men in the same situation, because it alerts women to the expectation of lower competence and status than men. A woman being condescended to, unacknowledged by, or interrupted by a man fits status superiority and inferiority expectations in society (Wagner & Berger, 1997), while this is not so for a man being treated similarly by a woman. Specifically, women receivers may see competence-questioning behaviors as reflecting sexism, whereas men receivers will be less likely to view the behavior as gendered. Joyce et al. (2020) echo this, noting that accusing someone of mansplaining rather than accusing them of being condescending is pointing directly to an underlying sexist assumption that women are less knowledgeable.

To conclude this section, we can apply SCT to explain why women receivers of competence-questioning interactions interpret such behavior as stemming from gender bias when performed by men.Footnote 1 This interpretation is not merely an attribution bias by women receivers, as these interactions may in fact be fueled by the unconscious bias of communication partners who are men, as explained by the PAC and Shifting Standards models.

Competence-Questioning Behaviors of Focus

As noted earlier, competence-questioning communication behaviors indicate doubt about another’s competence. These behaviors are distinct from overtly sexist communication behavior (e.g., sexist humor, Mitchell et al., 2004; or sexist remarks, e.g., making degrading statements about women in general; Swim & Hyers, 1999) because they are not direct statements about gender, but are instead reflecting a stereotyped expectation based on ascribed status. While there may be many ways competence can be questioned, in this paper we focus on three behaviors that have been described anecdotally as prevalent ways of subtly questioning the competence of women employees: condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, and interrupting behaviors. We highlight these behaviors as they are common examples acknowledged in corporate culture today as evidenced by media attention in outlets such as Harvard Business Review, Forbes, and Business Insider (e.g., Bain et al., 2021; Minor, 2021; Rath, 2017).

Condescending Explanation

Condescending explanations occur when an individual provides an explanation in a manner that conveys one believes that they are more intelligent or better than others (i.e., conveys a feeling of patronizing superiority). Thus, the behavior is labeled as condescending because of its assumed intent by the actor. These competence-questioning behaviors have been presented in the popular literature as often linked to gender.

The portmanteau “mansplaining” has proliferated on social media and Internet forums since its description in a 2008 essay by Rebecca Solnit (Bates, 2016; McNamara, 2017). Typically defined as “a man talking condescendingly to a woman” (Reagle, 2016), women have shared stories of mansplaining involving men explaining concepts of which the women already have knowledge, seeming to assume the women are unfamiliar with the topic (e.g., a client who is a man explaining muscle groups to a woman physical therapist; a news anchor who is a man explaining how COVID-19 is transmitted to a woman epidemiologist). In news articles, blogposts, and opinion pieces (e.g., Manne, 2020), mansplaining is presented as a gendered phenomenon which positions men as higher status and questioning the competence of women. However, the concept has been the focus of only a handful of scholarly articles spread across disciplines (e.g., Daddis, 2018; Imperatori-Lee, 2015; Preda, 2017; Reagle, 2016; Smith et al., 2022).

While there is a lack of research literature specifically on condescending explanations as a gender-linked phenomenon in the sense of them occurring more frequently from men toward women, one can surmise that condescending explanations are likely to elicit negative reactions from recipients. Additionally, such competence questioning in the presence of others can have subtle but deleterious effects on how an individual is viewed by others in the workplace.

Voice Nonrecognition

A second form of competence-questioning behavior is voice nonrecognition. Employee voice is discretionary employee expression of work- or organization-related content (e.g., speaking up; individual-level; Chamberlin et al., 2017) and can also refer broadly to processes that affect justice in the workplace (i.e., processes that empower employees to voice; organizational-level processes; Morrison, 2011). In contrast, voice recognition and nonrecognition has to do with how individual employee voice is received by individuals (e.g., supervisors, coworkers). While there is considerable research on gender differences in the extent to which individuals voice their ideas (see Eibl et al., 2020 for summary), the focus here is on recognition of voice that has occurred. According to Howell and colleagues (Howell et al., 2015, p. 1765), “voice recognition occurs when supervisors judge how much to acknowledge the pattern of discretionary input they have received from each of their employees;” voice nonrecognition would be ignoring or downplaying input. Voice nonrecognition may be considered a specific form of workplace incivility, which includes rude and discourteous behavior (Andersson & Pearson, 1999), or could be an element of abusive supervision (i.e., subordinate perceptions of supervisors’ repeated hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, Tepper, 2000, p. 178). However, those constructs address a broader range of repeated patterns of behavior, not necessarily targeted toward women.

Howell et al. (2015) found evidence that supervisors use employees’ peripheral features (e.g., ethnicity, gender) to determine the value of employee voice contribution, and that such judgments can result in less recognition of minority or disadvantaged employees (i.e., ignoring or failing to give credit). While Howell and colleagues did not find less recognition of voice from women than men, the organization examined in their study was majority-women. Others have found that ideas offered by men get more attention than those voiced by women (Simpson & Lewis, 2005). Guarana et al. (2017) demonstrated that managers responded more favorably to voice from those of the opposite gender if they were high in social comparison orientation (i.e., “inclination to compare one’s accomplishments, one’s situation, and one’s experiences with those of others,” Buunk & Gibbons, 2007, p. 16), but less favorably if they had weak social comparison orientation, perhaps because of greater outgroup distrust.

Research on voice nonrecognition has typically focused on upward voice, or voicing to supervisors, but it is important to address the potential implications of speaking up and being ignored by others, including coworkers and clients. Tannen (1994) examined gender in more general conversation contexts, finding women’s contributions are often ignored or not recognized. Being ignored, despite attempting to exercise voice, may have deleterious effects on participation in the workplace. Individuals likely will withhold their ideas and contributions (i.e., stop enacting voice) if they are continuously barred by others from expressing their ideas, their ideas are ignored, or their ideas are appropriated by others (e.g., Sandberg & Grant, 2015; Saunders et al., 1992). Morrison et al. (2011) found that shared beliefs regarding how acceptable it is to give thoughts and suggestions in a group (i.e., group voice climate) enhanced the relationship between how closely an individual identifies with the group and the likelihood of expressing their thoughts and opinions. Thus, if the voices of women in a workgroup are not registered or taken seriously (i.e., voice nonrecognition), then women may both be perceived as contributing less and may subsequently choose to voice or contribute less in future interactions.

Interruption

Interruption involves the deliberate stop** or hindering of another’s speech such that there is a break in the continuity, or the speaker’s turn is disrupted (Smith-Lovin & Brody, 1989). Interruption has also been described as a subtle, gender-linked behavior (under the term manterrupting; Bennett, 2015) meant to convey that one’s point of view is not as valuable (i.e., one is less competent). Farley (2008) conducted two experiments demonstrating that interrupting behaviors have clear implications for ascribed status. She found that overall, interrupters were perceived as possessing higher status compared to those who were interrupted, and participants even rated themselves as lower status and less competent if they were the ones being interrupted. If individuals are seen as targets of interruption, then they may also be viewed as less competent by others and themselves.

Some research evidence suggests that men are more likely to interrupt women than women are to interrupt men. For example, Smith-Lovin and Brody (1989) found that the odds of men attempting to interrupt women (0.163) were higher than women attempting to interrupt men (0.146; p. 430). Their results also indicated that women attempt to interrupt men and women speakers at similar rates, while men were twice as likely to interrupt a woman speaking compared to a man speaking. Examining conversation dyads, Zimmerman and West (1975) found that cross-gender dyads demonstrated a greater number of interruptions with nearly all interruptions initiated by the man. At the same time, same-gender dyads had far fewer interruptions, which were nearly equal between speaking partners.

Other research cautions against claiming gender differences in interrupting behavior and calls for a focus on the nature and context of the interruption (Dindia, 1987; Hancock & Rubin, 2015; Karakowsky et al., 2004; Kitzinger, 2007; Marche & Peterson, 1993). Indeed, James and Clarke (1993) reviewed studies from 1965 to 1991 and concluded there was no unambiguous evidence that men used interruptions to dominate interactions more so than women. Their research suggests that interrupting can occur for many reasons (e.g., support, clarification seeking), and not all would be seen as competence-questioning. Those who interrupt may be viewed more negatively and those who are interrupted viewed as less assertive and more vulnerable, but these perceptions were not associated with gender (Robinson & Reis, 1989).

In summary, competence-questioning behaviors performed by men and directed toward women have been of keen focus in popular press and social media outlets. These behaviors have popularly been labeled to convey that they are gendered in nature; however, research on whether or when these behaviors are reflective of sexism is either scant or mixed. In the next sections, we present several studies to consider that possibility.

Study 1

The goal of Study 1 was to gather critical incidents focusing on woman workers’ experience of receiving condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, and interruption, as perpetrated by men. In doing so, we document that these competence-questioning behaviors seen as linked to gender stereotypes do occur in the workplace and provide some comparison across the three behaviors. We specifically chose to ask women about instances where men were the initiators of the three types of competence-questioning behaviors, as the gendered nature of the context was what we wished to describe. We also explored potential antecedents of gender bias attributions.

Study 1 Method

Transparency and Openness

We describe here, in the appendices, and/or in the supplementary materials our sampling plan, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study. We adhered to the Journal of Applied Psychology methodological checklist. Research materials are available by emailing the corresponding author. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS (v26 and v27) and Mplus (v8). This study’s design and its analysis were not preregistered.

Participants

A total of 385 women were recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform, a source for participants comparable in quality to traditional data samples (Buhrmester et al., 2011; Paolacci et al., 2010). Our study incorporated several best practices for online data collection (Aguinis et al., 2021) including the use of screener items (Appendix 1), approving/denying submissions in a timely manner, providing explanations when rejecting submissions, and prompt responses to worker concerns. All participants were US residents, at least 18 years old, currently employed, and were able to identify and describe a condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, or interruption behavior by a man directed toward them while in a work-related context in the past six months. Participants who failed to follow directions or provided an incident that did not fit the behavior definition were removed (n = 21), leaving a final sample of 364 for analyses (Mage = 33.49, SD = 8.98; 72% White; 84% heterosexual).

Participants’ average length of tenure at the workplace where the incident occurred was 5.10 years (SD = 4.90), and 89% of respondents currently worked in the same organization as where the described incident occurred. Job titles held by participants ranged widely from accountant to sommelier to sign language interpreter. When asked for type of workplace (industry), the top five multiple choice responses were Other Services (18.4%), Retail (16.5%), Technology (15.9%), Other-Specify (13.7%; some examples mentioned multiple times included finance, legal/law, government), and Education (10.7%).

Procedure

Three versions of the survey were developed for each communication behavior type (condescending explanation, n = 117; voice nonrecognition, n = 122; interruption, n = 125), with the intention of relative equivalency in number of instances across the three examined behaviors. Following the conclusion of the survey, each participant read a debriefing page and received $1.50 in exchange for participation lasting for a median of 14.05 min (excluding 8 outliers). Participants were not given a time limit on how long they took to complete the survey and could take breaks during the survey if desired.

Measures

Incident Description

Participants were asked to describe in four to five sentences an incidence of condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, or interruption by a man in the workplace within the last six months (Appendix 2). Other open-ended items asked participants to write in one to two sentences how they responded to the incident, how they felt, the setting of the incident, the topic of conversation at the time, and why they thought the other individual behaved in such a way. Multiple-choice questions prompted participants to give more detail about the incident, including whether the topic of communication was work-related, the extent of their knowledge on this topic, whether others witnessed the incident, and the gender of witnesses.

Clarity of Intent

Using a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = “Agree” to 5 = “Disagree”) comprised of four items developed for Study 1 (Appendix 3), participants rated how clear the intent of the communicator appeared (α = 0.76).

Metacompetence Perceptions

A five-point (1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”) Likert-type scale comprised of four items was developed for this study (Appendix 3) to assess the extent to which the participant perceived the other individual viewed the participant as competent (α = 0.82). To address construct validity of both newly developed scales (i.e., clarity of intent and metacompetence perceptions), a confirmatory factor analysis in Mplus 8 was conducted across the eight total items as loading onto the respective two predicted factors, with model fit indices largely in line with or close to standard conventional cut-offs (CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.87, RMSEA = 0.12, SRMR = 0.06).

Workplace Incivility

Cortina et al. (2001; α = 0.91) seven item measure of workplace incivility was assessed via a five-point (1 = “Never” to 5 = “A great deal”) frequency scale. An example item is “Within the last year at work, have you been in a situation where anyone in the workplace made unwanted attempts to draw you into a discussion of personal matters?” Workplace incivility was measured as a contextual variable, as past research has linked gender biased behavior such as harassment with greater workplace incivility (Lim & Cortina, 2005).

Other Items

Participants were asked their hierarchical status at work in comparison to the communicator. Eleven percent reported being senior in status to the other person, 37.1% reported being equal in rank, 45.6% reported being junior in status, and 3% reported “Other” (e.g., other person was a customer, service provider, etc.). A planned contrast of incident type and rank did not indicate differences in proportions of ranks for different incident types, F(2, 338) = 1.12, p = 0.331. However, specifically for the behavior of condescending explanation, a plurality of respondents indicated that they were equal in job status to the communicator (44.4%), and for voice nonrecognition, most respondents indicated they were junior in work status to the communicator (62.3%). For interrupting, a plurality of respondents indicated they were junior in work status (43.7%).

Participants also rated how close their relationship was to the communicator on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = “complete stranger,” 7 = “a good friend”) for one item (M = 4.11, SD = 1.19). A plurality of respondents indicated that they worked regularly with this person, but they are not friends (41.2%).

Additionally, 51.4% of respondents indicated that they felt the communicator did not know how they felt about the incident. Most respondents indicated the topic of conversation was directly work-related (82.7%), that they were knowledgeable about the topic (M = 5.61, SD = 1.12; 1 = “Novice,” 7 = “Expert scale”), and that at least one other person was present during the incident (72.3%). Of those who reported others being present, 34.9% indicated that those present were all men or mostly men, 30% indicated that others present were all women or mostly women, and 35% indicated that the group was about equally men and women.

The percentage of men in the entire organization where the incident took place, as reported by each participant, was an average of 54.1% with wide variability (SD = 21.82). Finally, 55.8% reported that they have pointed this type of behavior out in the workplace before, though this did not necessarily mean that they pointed out this incident specifically, nor did this specify to whom they pointed this behavior out.

Results

Table 1 provides exemplar incidents of condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, or interrupting. Table 2 presents bivariate correlations, means, standard deviations, and reliabilities for measures. Missing data was treated with listwise deletion.

Two research assistants trained by the authors coded responses to open-ended questions regarding the incident according to inductively, iteratively derived themes, feelings in reaction to the incident, setting of the incident, and why the respondent thought the perpetrator behaved the way he did. Overall rater agreement was 73%, and agreement for individual variables within each incident category varied from 66 to 85%. Consensus of 70% or higher has been considered acceptable (e.g., Stemler, 2004). Discrepancies between coders were resolved with a third rater (one of the authors). Most participants described their feelings in relation to the incident as anger or annoyance (50.5%), sadness or hurt (21.7%), or embarrassment (13.2%). Most incidents occurred either in a formal meeting/conference (34.3%) or at the participant’s desk/office (28.3%). The third most common incident setting was informal work conversation (i.e., watercooler, breakroom, lunch; 14.0%). The remaining incidents occurred at someone else’s desk/office, some “Other” setting, or missing.

Participants’ qualitative answers were also coded for the main attribution made for the communicator’s behavior. Most attributions were categorized as one of two themes: being sexist/biased against women (28.3%) or being a jerk/rude person (39.3%). Other attributions included feeling the communicator was uninterested in the participant’s suggestion or idea (9.1%) or the communicator was unaware of themselves/just trying to help (9.6%). The remaining attributions were categorized as other (11.5%; e.g., “He…didn't want to make any changes which would be time consuming.”) or missing.

Coders also categorized the topical content for condescending explanation incidents specifically. Topics ranged from stereotypically masculine topics (e.g., sports, cars, construction, equipment; 21.4%) to stereotypically feminine topics (e.g., parenting, cooking, women’s health; 5.1%). However, the most prevalent topic was “my job or my tasks at work” (47.6%), with an additional 22.2% regarding computers/technology specifically. Sexist attributions were lower (Mwork = 0.21, SD = 0.41; Mnonwork = 0.41, SD = 0.50; t(114) = − 2.32, p = 0.011) and meta-competence perceptions were higher (Mwork topic = 2.00, SD = 0.89; Mnonwork = 1.63, SD = 0.70, t(111) = 2.50, p = 0.014) for work-related topics as compared to non-work topics.

To explore potential antecedents of gender bias attributions, a logistic regression was conducted in SPSS with attributions to bias as the outcome (coded as 1 = sexist/biased against women, 0 = nonsexist; see Table 3). Step 1 included communication behavior type (i.e., condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, or interruption) as a predictor. Step 2 included respondents’ ratings of clarity of intentions (around the perpetrator’s actions) and respondents’ ratings of metacompetence as predictors. Finally, step 3 predictors included two contextual variables (i.e., workplace incivility ratings and participant-reported percentage of men in the workplace). Two significant predictors emerged: communication behavior type and percentage of men in the workplace. Table 3 indicates that respondents reporting a greater percentage of men in the workplace were 1.01 times more likely to interpret the behavior as biased against women. A post-hoc ANOVA of attributions by incident type (effect coded) revealed that communicator behavior in both condescending explanation [t(361) = 3.05, p = 0.003] and voice nonrecognition [t(361) = 4.46, p = 0.000] incidents were interpreted as significantly more gender-biased than in interruption incidents, while condescending explanations and voice nonrecognition incidents did not significantly differ in respondents’ gender bias attributions, t(361) = − 1.36, p = 0.176.

Participants’ open-ended responses to the item “What, if anything, did you say or do in response to [the incident]?” were coded as 0 = did not confront and 1 = confronted or alerted someone outside the situation. Most respondents reported doing nothing in response to the incident (52.4%; e.g., “I was so annoyed that I didn’t say or do anything in response because I was afraid that I might cause a scene. Since it was the workplace, I just kept my mouth shut and went about my day.”). However, 38.5% reported confronting (or attempting to confront) the individual (e.g., “After he was so condescending, I paused, took a deep breath, and let him know that I had over a decade of experience in this very matter and could handle it just fine and needed him to stay in his own lane and do his own job.”; “I took him aside and warned him to never interrupt me again and pointed out that he screwed up with the patient. I said either we work together, or I will make a complaint.”), while 4.9% alerted someone outside the situation, and 4.4% provided other or no information on their actions. There was no significant difference (p = 0.067) in response/confronting between those that attributed the behavior to gender bias and those that did not.

Study 1 Discussion

The purpose of Study 1 was to document the nature and occurrence of competence-questioning behaviors as perpetrated by men toward women in the workplace. Study 1 results suggest that condescending explanations and voice nonrecognition were more often seen as attributable to sexism than interruptions, particularly in men-dominated workplaces.

We found some evidence of important contextual factors, specifically that competence-questioning behaviors occurred more often when women were junior or equal to (rather than senior to) the communicator in work status, and most often occurred in the presence of others and focused on work-related topics. It could be that women in higher status positions are granted greater perceived competence, or that men workers still question their competence, yet do not engage in competence-questioning behaviors because these women are in positions of relatively higher power. The finding that this these behaviors occurred more often in group settings may also be explained by Status Characteristics Theory. Men as a group with higher ascribed status may play into expectations of their competence and dominance by publicly questioning the competence of the lower ascribed status group (i.e., women). Moreover, we can extend older research on interruptions and gender to these behaviors which suggests that men and boys (vs. women and girls) are more likely to interrupt in a group (3 or more) as a way to establish dominance (Anderson & Leaper, 1998; Smith-Lovin & Brody, 1989). Work-related topics may be associated with increased competence-questioning simply because they are more common in the workplace. On the other hand, again drawing on interruption research, men may be more likely to perpetuate competence-questioning for instrumental or problem-solving tasks (e.g., work-related; Anderson & Leaper, 1998). In Studies 2 and 3, we examine whether competency-questioning behavior is perceived differently depending on communicator and recipient gender.

Studies 2 and 3

Studies 2 and 3 employed experimental designs to consider whether the same competence-questioning communication behavior performed by a man or woman is perceived differently, and whether those perceptions differ based on the gender of the recipient of the behavior.

SCT (Berger et al., 1977) and traditional gender roles would suggest that gender is a characteristic that affects how individuals view the status of women and men in a group. That is, traditional binary gender as a status characteristic would create expectations for the higher status of men and the lower status of women. Further, the PAC (Goodwin et al., 2000) and Shifting Standards (Biernat & Fuegen, 2001) models explain why individuals, particularly those holding more power or status (in the case of gender, men), would ignore, downplay, or penalize those with lower status (i.e., women). In our case, we envision competence-questioning communication behavior as a way to express this. From the view of the recipient of competence-questioning communication behavior, SCT posits that those possessing characteristics indicating lower status are aware of their standing and react accordingly. Specifically, those ascribed lower status (i.e., women) are likely to identify the communication behavior (condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, interruption) as a judgment of one’s competence. Thus, we hypothesized:

-

Hypothesis 1: Recipients’ interpretations of communication behaviors as questioning one’s competence will be greatest where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 2, 3)

Further, recipients will likely make gender bias attributions regarding the competence-questioning behavior in line with SCT, the PAC model, and the Shifting Standards model, as well as the existing anecdotal evidence regarding the gendered nature of these behaviors. We further hypothesized:

-

Hypothesis 2: Recipients’ attributions of communication behaviors to gender bias will be greatest where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 2, 3)

We measured affective and behavioral consequences of competence-questioning as well. We anticipate that recipients will react most negatively to competence-questioning communication behaviors when the recipient is a woman (a member of the expected lower status group) and when the communicator is a man (a member of the expected higher status group). We expect that recipients will have negative affective (high negative affect, low positive affect) and nonverbal reactions in line with meta-analytic findings showing that perceived discrimination is associated with negatively valenced outcomes (e.g., lower job attitudes, lower psychological well-being; Schmitt et al., 2014; Triana et al., 2019). We further expect that participants, particularly women, will enact behaviors that show an inclination to withdraw from the setting (fewer words contributed in a group setting, less likelihood to want to continue working with the communicator) in reaction to competence-questioning. This follows from research on “pushed out/opt out” phenomena which suggest that in the face of bias or perceived lack of fit women will avoid or withdraw from a role or setting (e.g., Kossek et al., 2017).

-

Hypothesis 3a: Recipients will have the greatest negative affect in reaction to communication behaviors where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 2, 3)

-

Hypothesis 3b: Recipients will have the least positive affect in reaction to communication behaviors where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 2, 3)

-

Hypothesis 3c: Recipients will exhibit the greatest discomfort (facial expressions, nonverbal engagements) in reaction to communication behaviors where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 3)

-

Hypothesis 3d: Recipients will withdraw from the setting (speak fewer words, express the least willingness to work with the communicator again) in reaction to communication behaviors where the recipient is a woman and the communicator is a man. (Study 3)

A general model illustrating the hypotheses is provided in Fig. 1. Study 2 employed written vignettes to assess hypotheses 1, 2, 3a, and 3b, while Study 3 examined all hypotheses in the context of a face-to-face behavioral interaction.

Study 2 Method

This experiment was a 2 (Recipient/Participant gender: man vs. woman) × 2 (Communicator gender: man vs. woman) × 3 (Communication behavior: condescending explanation vs. voice nonrecognition vs. interrupting) factorial between-subjects design. A sensitivity analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.2 indicated a minimum detectable effect size of f = 0.23. The Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) statement made for Study 1 in the Study 1 Method section fully applies to Studies 2 and 3.

Participants

We collected responses from 720 adults recruited from MTurk. Purposeful sampling allowed an even gender breakdown within our sample (50.8% women). After removing participants who failed attention and manipulation checks (n = 218), a total of 502 participants remained. All participants were US residents, at least 18 years old, and employed. Average participant age was 35.98 (SD = 10.10) years, most participants were White (81.3%) and most identified as straight or heterosexual (89.6%). Participants were compensated $1.50. The median time participants took to complete the survey was 22.43 min (excluding 2 outliers). Participants were not given a time limit on how long they took to complete the survey and could take breaks during the survey if desired.

Procedure

Participants were asked to imagine that they were appointed to a small work committee to determine the allocation of bonus funds to deserving employees (Leaderless group discussion, n.d.). In preparation for a meeting with the committee, participants were tasked with reviewing descriptions of five employees under consideration. To encourage full and thoughtful participation, we asked participants to write descriptions detailing their perceptions of each employee under consideration, as well as their rationale behind a determination for fund allotment. Upon finishing their review and documentation, participants were asked to imagine entering a meeting with the other committee members to come to a final decision regarding bonus fund allocation. Participants were presented with short descriptions of the other committee members, specifically one man and one woman described as members of the same department as the participant with equal levels of seniority. Pictures of these fictional committee members were provided to add an element of realism (previously pilot tested as equivalent on attractiveness and perceived age, Gardner & Ryan, 2020). Participants were then told that either the man or woman committee member enacted one of the three communication behaviors targeted at the participant, dependent on their experimental condition (described in Appendix 4). Participants then answered open-ended questions and completed measures with respect to the incident, before providing their demographic information and receiving compensation.

Measures

Positive and Negative State Affect

To assess recipient (i.e., participant) affect, participants completed Watson et al.’s (1988) Brief PANAS measure. While the PANAS was originally used to capture trait affect, it is often used to study state affect as well (e.g., Rossi & Pourtois, 2012). Researchers assume that state and trait affect have similar psychological structures (Silvia & Warburton, 2006). In the current study, we targeted affect in response to a specific event, necessitating a focus on state affect. This 20-item measure included ten items to assess positive affect (α = 0.90), and ten items to measure negative affect (α = 0.90), all measured on a five-point Likert-type scale. Specifically, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they were experiencing each affective state in response to the previously described situation (1 = “Very slightly to not at all” to 5 = “Extremely”). An example item for positive affect is “excited,” while an example item for negative affect is “upset.”

Metacompetence Perceptions

The 4-item metacompetence measure developed for Study 1 was administered for Study 2 with minor adaptations (Appendix 3) and acceptable reliability (α = 0.80; 1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”).

Gender Bias Attributions

To assess the extent to which recipients (participants) attributed the communication behavior to gender bias, participants completed a two-item, seven-point Likert-type scale developed for this study (α = 0.83; 1 = “Extremely unlikely” to 7 = “Extremely likely”). Specifically, participants rated the likelihood that the following two statements were true: “My coworker is biased against my gender” and “My coworker has issues with being on teams with members of another gender group.”

To address construct validity of developed scales within Study 2 (i.e., metacompetence and gender bias attributions), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis in Mplus 8 to ensure the six total developed items loaded onto the two constructs as anticipated; model fit indices were again primarily in line with traditional cutoff conventions (CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04), supporting the predicted factor structure of these variables.

Study 2 Results

Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 4.Footnote 2 Missing data was treated with listwise deletion. We conducted a three-way MANOVA in SPSS with communicator gender, communication behavior type, and recipient (i.e., participant, the target of the behavior) gender as the factors impacting the recipient’s metacompetence perceptions, gender bias attributions, and affect outcome variables (Table 5) to assess hypotheses 1, 2, 3a, and 3b.

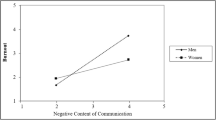

Hypothesis 1 suggested that interpreting the communication behaviors as questioning one’s competence would differ depending on communicator and recipient genders. The main effects of communicator gender and recipient gender on metacompetence perceptions were not significant. There was a main effect of communication behavior type on metacompetence perceptions, but it was qualified by an interaction effect between behavior type and recipient gender, F(1, 468) = 3.61, MSE = 3.36, p = 0.028. Post-hoc analyses revealed that for the condescending explanation behavior only, women recipients felt their coworker perceived them as less competent than did men recipients (Fig. 2), t(161) = 2.17, p = 0.032, Hedge’s g = 0.34. Effects for voice nonrecognition and interrupting behaviors were not significant. While the interaction posited in hypothesis 1 was not found, results for one of the three behaviors (condescending explanation) suggest the role of gender in interpretation.

Study 2 Metacompetence perceptions by communication behavior type and recipient gender. Metacompetence rated on a five-point Likert scale. Post hoc analyses indicated a significant difference between women and men recipients’ metacompetence perceptions for the condescending explanation behavior only (Hedge’s g = .34)

Hypothesis 2 suggested that recipients would have the greatest gender bias attributions if the communicator was a man and the recipient was a woman. Results demonstrated that women recipients were more likely to attribute communication behaviors to gender bias than were men recipients, and recipients reported greater gender bias attributions for men communicators. However, these main effects were qualified by an interaction between communicator gender and recipient gender, F(1, 468) = 44.00, MSE = 118.75, p = 0.000. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the difference in gender bias attributions between men and women communicators was significant only for women recipients, t(250) = 8.26, p = 0.000, Hedge’s g = 1.04, showing that women recipients believed the communicator was more motivated by gender bias when the communicator was a man (Fig. 3). Thus, hypothesis 2 was supported.

Additionally, there was a significant main effect of communication behavior type on gender bias attributions, F(2, 468) = 4.46, MSE = 12.04, p = 0.012, with post-hoc comparisons revealing that mean differences in gender bias attributions were highest for the condescending explanation (M = 3.95, SD = 1.71, pvoice = 0.044, Hedge’s g = 0.22; pinterrupt = 0.002, Hedge’s g = 0.33), while there was no significant difference in attribution between the voice nonrecognition (ignoring; M = 3.57, SD = 1.80) and interrupting conditions (M = 3.37, SD = 1.83).

Hypotheses 3a and 3b stated that recipients would experience the greatest negative and least positive affect when the competence-questioning behavior is coming from a communicator who is a man toward a recipient who is a woman. Significant main effects on negative affect were qualified by an interaction effect based on communicator gender and communication behavior type, F(2, 468) = 5.51, MSE = 2.81, p = 0.004 (see Fig. 4). Post-hoc t tests by communication behavior type show that there was only a significant difference in negative affect by communicator gender for the condescending explanation behavior. For condescending explanation behavior, negative affect was significantly higher when the communicator was a man (vs. a woman; t(161) = 3.27, p = 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.51). Results of the MANOVA did not indicate any significant effects for positive affect. While hypothesis 3b was not supported, findings from the test of hypothesis 3a suggest that communicator gender plays a role in affective responses to competence-questioning.

Study 2 Discussion

The experimental design of Study 2 allows us to infer women recipients of these behaviors view the communicator as more gender biased if the communicator is a man, but this is not the same case for the opposite scenario (a recipient who is a man and a communicator who is woman). Furthermore, in cases of condescending behavior, women see the communicator as questioning their competence more so than do men, and individuals in general feel more negative after a condescending explanation than being interrupted or not having one’s voice recognized.

Though the vignette design of Study 2 limited realism, steps were taken to give the participant more context, such as providing pictures of coworkers and descriptions of coworker backgrounds. Additionally, participation in the bonus allotment task prior to the competence-questioning manipulation was intended to maximize participant involvement within the study and to increase realism within the work context. Finally, participants were asked to provide several thoughtful open-ended responses about their reaction to the scenario directly after reading about the interaction.

While Study 2 provided some indication of the role of gender in interpretation of competence-questioning behavior, the vignette design may not have elicited the same reactions as occurring in face-to-face communication; in Study 3, we conducted an in-person experimental study using confederates to simulate a real-life work group for participants. Given the demands of data collection with multiple confederates, only one communication behavior was examined. As condescending explanations exhibited the strongest affective reactions and gender differences in Study 2, we focused on this communication behavior specifically in Study 3.

Study 3 Method

The experiment was a 2 (Recipient/Participant gender: man vs. woman) × 2 (Communicator gender: man vs. woman) factorial between-subjects design. Participants were randomly assigned a condition where the communicator was a man or a woman.

Participants

Individuals from the research pool of a large midwestern university participated in exchange for course credit. Participants were removed based on four attention checks (e.g., “Please choose Option 5”; n = 40). The final sample of 128 participants was 50.8% women, 88.3% heterosexual, and on average 19.02 (SD = 1.04) years old. The sample was racially diverse,Footnote 3 with 57.8% identifying as White, 13.3% as Black, 12.5% as East Asian, 10.9% as South Asian, 4.7% as Hispanic, 3.9% as Middle Eastern or Arab, and 0.8% as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (participants chose all race/ethnicities that applied). A sensitivity analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.2 indicated a minimum detectable effect size of f = 0.37.

Procedure

Please refer to Appendix 5 for a detailed description of the procedure. After signing the informed consent to participate and be video recorded, the experimenter provided the same group-decision making task as in Study 2. First, the participant (Coworker #1) and confederates (Coworker #2 and #3) were given time to privately write down their answers to the task. The experimenter then instructed the participant to begin the first discussion segment by explaining their answers for the task (as the true participant was always labeled as “Coworker #1,” allegedly at random) and left the room after turning on the video camera. Once the participant finished with their initial comments, Coworker #2 (the confederate designated as the condescender for that session) spoke the following lines:

So, I don’t think you’re really understanding the task. It said that you’re supposed to divide the extra money between all the employees. You’re supposed to decide how much of a bonus you think each employee deserves.

The two confederate group members then recited scripted lines regarding their opinions on the task. Unlike Coworker #2, Coworker #3 (the remaining confederate designated as the noncondescender) was not given any scripted lines that address the performance of the participant (Coworker #1). After 5 min, the experimenter returned to the room and had the participant and confederates fill out a survey in reference to each of their two coworkers. Participants were then told there would be no more discussion segments, debriefed, and assured that their competence was not under question.

Multiple choice items demonstrated that 48.4% of participants believed the condescending communicator (Coworker #2) was rude and 56.3% believed the condescending communicator behaved condescendingly in the discussion. The ambiguous nature of the behavior means that individuals are expected to differ in their interpretation of that behavior when directly asked; our focus is on whether such behavior has effects on other outcomes. In contrast to the condescending communicator, only 1.6% and 12.5% of participants believed the noncondescending communicator (Coworker #3) present in the group (see Procedure) was rude or behaved condescendingly, respectively. Additionally, further analyses in the online supplementary materials demonstrated that participants had more positive reactions to the noncondescending communicator over the condescender. Thus, participants perceived the condescender as rude or condescending in comparison to a neutral person (the noncondescender) in support of the manipulation.

Measures

The same measures for positive state affect (α = 0.90), negative state affect (α = 0.75), metacompetence (see Appendix 3 for adaptation; α = 0.69), and gender bias attributions (α = 0.77) as in Study 2 were completed in reference to the communicator enacting the competence-questioning behavior. As was done in Study 2, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis in Mplus 8 to ensure developed metacompetence and gender bias attribution items loaded onto their respective variables as predicted; model fit indices supported our predicted factor structure (CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.03, RMSEA = 0.00, SRMR = 0.04).

In addition, participants also answered two items designed to assess how likely they would be to want to work with the coworker in the future: “I would be willing to participate in another group discussion with Coworker X” and “If I were choosing individuals to be in another group discussion with, I would choose Coworker X” (1 = “extremely unlikely,” 7 = “extremely likely;” α = 0.87).

Video Coding

Four undergraduate research assistants, who were not confederates and were blind to hypotheses, were trained and watched each video three times to code for visible facial expression (yes/no), number of words spoken, frequencies of engagement (looking and nodding) with each of the confederates, and participant verbal confrontation (yes/no). Each video session was coded by 2 raters. For the binary variable of verbal confrontation, raters agreed 94.2% of the time; for having a visible facial reaction to the condescending behavior, raters agreed 80.8% of the time. Any discrepancies were resolved by the first author.

ICC(1) was used to assess interrater reliability for continuous variables, as advocated by Landers (2015). ICC values were consistent with general guidelines for reliability: ICC(1) = 0.86 for number of words spoken by the participant after receiving the condescending explanation (M = 54.82, SD = 60.42) and ICC(1) = 0.70 for engagement (nods or looks) toward the communicator (M = 9.07, SD = 3.97).

Study 3 Results

Table 6 displays the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between variables. Effect sizes are reported in figures corresponding with analyses. Missing data was treated with listwise deletion. Within-person analyses exploring the potential differences between participant perceptions of the condescender (Coworker #2) as compared the noncondescender (Coworker #3) can be found in the online supplementary materials. Going forward, reference to the communicator is synonymous with the condescender (Coworker #2).

To test hypotheses, a multivariate general linear model, including recipient (i.e., participant, the target of the behavior) gender, and communicator gender as factors, with recipient’s (i.e., participant’s) positive affect, negative affect, metacompetence perceptions, gender bias attributions, likelihood to work with the person again, engagement (looks and nods), and words spoken as outcomes, was conducted in SPSS (Table 7). Overall, analyses revealed significant main effects for positive affect, metacompetence perceptions, attributions of gender bias, and likelihood of working with the person again based on recipient gender. No effects of negative affect (H3a) and engagement (i.e., looks and nods toward condescender; H3c) were significant. While there was not a significant main effect for words spoken, there was a significant interaction based on participant gender and communicator gender, elaborated on below.

For metacompetence perceptions [F(1,118) = 10.39, MSE = 4.91, p = 0.002], women recipients (M = 2.10, SD = 0.66) believed the communicator thought they were less competent compared to men recipients (M = 2.49, SD = 0.72; Cohen’s d = 0.56), regardless of communicator gender. No significant main effects for communicator gender or interactions were found, so the anticipated interaction from hypothesis 1 was not found.

For gender bias attributions [F(1,118) = 5.04, MSE = 10.34, p = 0.027], women recipients attributed the behavior of the communicator to gender bias more so than did men recipients. However, this effect was qualified by a significant interaction between recipient gender and communicator gender [F(1,118) = 7.41, MSE = 15.20, p = 0.007], such that recipients rated the communicator as more biased if the coworker was different gender (see Fig. 5). Post-hoc analyses revealed that the difference in gender bias attributions between men and women communicators was only significant when the recipient was a woman [t(63) = 2.76, p = 0.008; Hedge’s g = 0.69]. These results support hypothesis 2, which stated that communications involving women recipients and men communicators would result in the greatest gender bias attributions.

Study 3 Gender bias attributions by recipient gender and condescender gender. Post hoc analyses revealed that the difference in gender bias attributions between men and women communicators was only significant when the recipient was a woman (Hedge’s g = − .69). Gender Bias Attributions was rated on a seven-point Likert scale

Hypothesis 3a was not supported as there was no main effect or interaction of communicator gender on negative affect. For positive affect [F(1,118) = 4.51, MSE = 2.89, p = 0.036], women recipients (M = 2.03, SD = 0.79) indicated less positive affect toward the communicator than did men recipients (M = 2.35, SD = 0.81; Cohen’s d = 0.40), also failing to support the interaction in hypothesis 3b, but indicating that recipient gender had a role in affective reactions.

A logistic regression was conducted to analyze the binary outcome of whether the recipient had a visible facial reaction to the condescending explanation, finding a significant effect for recipient gender (B = − 0.52, SE = 0.44, Wald = 5.49, p = 0.019, Nagelkere R2 = 0.07), but not for communicator gender. Men recipients were 0.60 times less likely to show an emotional facial reaction to condescension compared to women; overall, 25% of recipients visibly reacted to the condescending treatment. These results indicate that hypothesis 3c for the outcome of facial expressions was not supported, but again do suggest the role of gender in response to competence-questioning behavior.

There was a significant interaction effect of recipient gender and communicator gender on the outcome of average words spoken by the participant after the behavior occurred, [F(1,118) = 5.90, MSE = 21,099.83, p = 0.017]. Post-hoc analyses indicated the effect was only significant for women participants [t(59) = − 2.79, p = 0.007; Hedge’s g = 0.72] as women recipients spoke fewer words in response to the communicator when the communicator was a man (Fig. 6). Thus, hypothesis 3d was supported for the outcome of number of words spoken.

For likelihood of working with the communicator again [F(1, 118) = 6.80, MSE = 22.92, p = 0.010], women recipients (M = 3.17, SD = 1.81) indicated they would be less likely to opt to work with the communicator again than would men recipients (M = 4.03, SD = 1.75; Cohen’s d = 0.48), regardless of communicator gender. While the interaction expected by hypothesis 3d was not found, there is evidence of the influence of gender on this outcome.

Overall, hypothesis 3 was partially supported in that conditions with women recipients and/or men communicators resulted in lower positive affect, greater discomfort (words spoken, facial expressions), and less willingness to work with the communicator again, though hypothesis 3 was not supported for negative affect and nonverbal engagement (i.e., looks and nods toward communicator).

We also explored the frequency at which recipients verbally confronted the communicator, finding only 16.4% of recipients engaged in confrontation. A logistic regression did not indicate any differences in the rate of confronting based on recipient gender or communicator gender. Examining bivariate correlations (Table 6), verbally confronting the communicator was negatively correlated with likelihood of working with the communicator again (r = − 0.21, p = 0.023) and positively correlated with words spoken (as expected, r = 0.20, p = 0.028).

Overall Discussion

While the popular press has indicated that communication behaviors based in gender bias may be prevalent in the workplace, surprisingly little research has examined competence-questioning behaviors. In Study 1, we documented incidents of these behaviors enacted by men toward women and showed that while these behaviors do elicit negative reactions, there is variability in whether they are attributed to gender bias (i.e., not all condescending explanations from men are seen as due to sexism). Behaviors can be attributed to traits of the communicator (e.g., jerk, arrogant) or to contextual influences (e.g., time pressure). However, the neologisms of focus in the popular press are applicable when the communication behavior is seen as questioning one’s competence with roots in gender bias.

Across Studies 2 and 3, we see evidence that women recipients are more likely to interpret the communication as competence-questioning, as attributable to gender bias, and have greater negative reactions to it than men recipients. Less often, but in multiple instances across Studies 2 and 3, this effect of recipient gender was qualified by an interaction with communicator gender such that women recipients had the most negative perceptions (perceiving the greatest competence-questioning, greatest gender bias, and most negative reactions) when the communicator was different-gender (i.e., a man). Overall, our investigation showed evidence for competence-questioning behavior as a gendered phenomenon.

Of note, across Studies 1 and 2, condescending explanations stood out as a competence-questioning, gender-biased behavior relative to voice nonrecognition or interrupting; thus, answering our research question regarding differences between the behaviors. One reason condescension may have produced more of the expected pattern of findings than voice nonrecognition and interruption is that it is less ambiguous in motive and interpretation.

Voice non-recognition was not linked to gender bias attributions in Study 2; however, it was often seen as indicative of gender bias in our real-world incidents documented in Study 1. This may be because of the short-term nature of relationships in Study 2; voice nonrecognition may be interpreted differently in the context of ongoing work relationships than in ad hoc committees and short-term interactions. While a lack of strong reaction to voice nonrecognition may also be a result of conversation-facilitation desires, it can also reflect a concern about whether one’s ideas were good ones, in line with research that women characterize themselves in more stereotypic terms regarding instrumental competence (i.e., productive, effective; Hentschel et al., 2019). Furthermore, of the three behaviors examined, voice nonrecognition is arguably the most subtle and ambiguous as it is more of an omission (e.g., failing to properly acknowledge, completely ignoring) rather than an actively performed (e.g., providing an explanation, stop** someone who is speaking). This ambiguousness may have allowed participants to generate more possible attributions for the behavior, making them less likely to definitively react (e.g., with negative or positive affect).

For interruptions, research has indicated that conversational reactions largely depend on target perceptions, as interruptions can be positive and affiliative (e.g., indicating support, “I totally agree”), anticipatory (e.g., finishing one’s thoughts), or negative and dominance-linked (e.g., changing topics, intruding on one’s points); thus, playing a status-organizing role (Farley et al., 2010). Though the interruption itself was similar across conditions within our experimental study, some research suggests that men’s interruptions of other men are more affirming, while their interruptions of women are more negative (Smith-Lovin & Brody, 1989). Looking more closely at interactions of questioner, recipient, and nature of the interruption may shed more light on the link between gender and interruption. Some communication research (e.g., Smith-Lovin & Brody, 1989) does suggest that women who are interrupted tend to engage in conversation facilitating behaviors (e.g., smiling, nodding), perhaps from agreement with the interrupter, but possibly to “hurry the speaker along” to have a chance to take back the floor (Farley et al., 2010). Thus, while our aim was to create an interruption that would be seen as asserting status and dominance, the general tendency of women to facilitate conversations may have predominated their reactions to the interruption.

In terms of consequences of these behaviors, women (vs. men) recipients indicated lower positive affect (Study 3) and lower metacompetence perceptions (Study 2 and 3) in response to condescension. If it is the case that women are more likely than men to be on the receiving end of competence questioning behavior or to react to it more strongly, there may be cases where it leads to self-derogating behaviors (e.g., low self-evaluation), impacts productivity, and has long-term career effects. For instance, Shastry et al. (2000) and Shifting Standards (Biernat & Fuegen, 2001) models by defining and directly studying specific competence-questioning behaviors that these theories imply. In doing so, we provide empirical evidence for the effects of these behaviors on recipients. Third, by applying SCT, PAC, and Shifting Standards to phenomena such as condescending explanation, voice nonrecognition, and interrupting behaviors, we have delineated a possible explanation why these behaviors are notoriously gendered from both the perspectives of the communicator and recipient. Our studies here specifically demonstrate how the behavior is interpreted, as well as the effects of viewing competence-questioning behavior as gendered from the recipients’ end; there is now an opportunity to further expand theory by investigating the communicator’s perspective. We also provide an example of how the microaggressions research might work to disentangle behavior and attributions, which has been a key critique of how that research has been conducted.

In terms of practical implications, managers might consider greater attention to when, where, and why competence-questioning behaviors occur. Discussions and trainings that focus on how to appropriately raise doubts about another’s actions or ideas and how to provide feedback can allow opportunities to discuss any gender links in enacting such behaviors, as well as give individuals the tools to ensure competent work occurs while providing psychological safety for others when raising critiques. Observational audits of meeting behaviors might also give work teams useful insights into whose ideas are incorporated and when gendered behaviors may be occurring. Such activities that would help assess the prevalence and impact of competence-questioning behavior at the organizational level should be seen as important. As aforementioned, competence-questioning behavior is likely to negatively influence employees’ job performance, job satisfaction, and work engagement (Judge & Bono, 2001; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). These behaviors may also have far-reaching consequences regarding others in the organization. For example, Systems Justification Theory (Jost & Banaji, 1994; Jost et al., 2004) would suggest that competence-questioning behaviors directed at disadvantaged groups in the workplace (e.g., women, minorities) are a way to maintain the status quo and perpetuate inequality, not only solidifying the status of advantaged members but also leading disadvantaged members to internalize stereotypes.

Several writers have considered how labels such as “mansplaining” (Solnit, 2014), “bropropriating” (Reeves, 2015), and “manterrupting” (Bennett, 2015), lead to social policing of gender norms. While their aim may be to highlight problematic behavior by men, there is debate as to whether the terms themselves are sexist as they imply these are things only men do (Bridges, 2017; Lutzky & Lawson, 2019). Going forward, researchers and practitioners may consider highlighting that while these behaviors occur across genders, when these behaviors are directed at a certain gender more often, or when these behaviors are attributable to stereoty** a certain gender as less competent, there is the potential for gender bias.

Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

In all, the results of this research have intriguing and concerning implications for theory and practice, though there were of course limitations. First, the results of experimental studies with newly formed groups may not generalize to workgroups that have a history of working together, but they may apply to ad hoc teams. At the same time, our Study 1 critical incidents from real-world employees do indicate that competence-questioning behaviors occur in a variety of work contexts, not just in short-term relationships.

Study 1 was designed to obtain a description of the phenomenon rather than to predict when it occurs and how individuals respond to it. Further work that more precisely measures responses (e.g., using identity management scales) can provide a more detailed picture of how competence-questioning communications are handled at work. Our Study 1 involved women retroactively recalling past incidents rather than reporting them in real time, so recall biases may be present (Edvardsson & Roos, 2001), although our set of questions asking for detail around the incident followed suggestions for minimizing memory distortion (Tanur, 1992). Future research involving experience sampling methodology, in which respondents are surveyed upon experiencing an event, may address this limitation by minimizing the time between incident and measurement.

Additionally, our investigation made use of some measures specifically designed for this study as appropriate established scales did not exist. Our scales had adequate reliability, CFA analyses displayed acceptable fit, and expected correlations with other study variables was found—all evidence of construct validity. Nevertheless, future studies may aim to further refine measures that capture relevant constructs for competence-questioning behaviors.

Future work that considers the perspective of both parties in an interaction and/or that uses a representative sample of the workforce to assess rates of occurrence of competence-questioning behaviors would be valuable. Studies that consider whether competence-questioning communication behaviors differ in nature or frequency for women of color, for women in diverse cultural contexts, for women at different hierarchical levels, for other gender identities, and for other identity groups where competence stereotypes exist are needed as well. As a first step, Smith et al. (2022) surveyed participants on the frequency of mansplaining in the workplace finding that men were indeed more likely to perpetuate mansplaining while women, especially women of color, are more likely to be targets.