Abstract

Nonreductive physicalism states that actions have sufficient physical causes and distinct mental causes. Nonreductive physicalism has recently faced the exclusion problem, according to which the single sufficient physical cause excludes the mental causes from causal efficacy. Autonomists respond by stating that while mental-to-physical causation fails, mental-to-mental causation persists. Several recent philosophers establish this autonomy result via similar models of causation (Pernu, Erkenntnis 81(5):1031–1049, 2016; Zhong, J Philos 111(7):341–360, 2014). In this paper I argue that both of these autonomist models fail on account of the problem of Edwards’s Dictum. However, I appeal to foundational principles of action theory to resuscitate mental-to-mental causation in a manner that is consistent with the models of causation endorsed by these autonomists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some frame the principles of mental causation and irreducibility in terms of mental events and physical events (Kim 2005, 42), while others frame these principles in terms of mental properties of events and physical properties of events (Fodor 1974, 100). I will frame these principles in terms of mental properties of events and physical properties of events, but nothing of substance rides on this distinction.

Irreducible mental causation is contrasted with reduced mental causation, where reduced mental causation is the conjunction of mental causation and the rejection of irreducibility: mental causes, as identical with physical causes, sometimes cause mental effects and physical effects. Irreducible mental causation, if possible, is preferable to reduced mental causation (cp. Silberstein 2001, 84; Lowe 1993, 631–632; McGinn 1989, 137). Indeed, even Jaegwon Kim, who ultimately endorses reduced mental causation, worries that reduced mental causation seems like “a form of mental irrealism” (Kim 1998, 199) that “all but banishes the very mentality it was out to save” (Kim 1995, 194).

Genuinely overdetermined events are events caused by two independent causal processes. Sally and Ted both throw rocks, which both smash the window at the same time. This is a case of genuine overdetermination, as these throws are independent of one another, and individually sufficient for the effect. By supervenience, however, m is not independent of p, so the causal exclusion principle does not permit p* to have both m and p as causes.

Some autonomists, including Zhong, provide additional nuance here. He agrees that mental-to-mental causation is true, and mental-to-physical causation is false, but he also endorses mental-to-higher-level property causation, which he thinks includes behavioural and social properties (Zhong 2014, 350). This position, however, still faces the same Edwards’s Dictum challenge discussed in Sect. 3 that the autonomist endorsing only mental-to-mental causation faces. Namely, for Zhong, higher-level behavioural properties would be completely determined by their lower-level subvenient physical bases, which would exclude mental properties of events from causally interacting with higher-level behavioural properties. For the sake of brevity, I will only discuss the autonomist who endorses only mental-to-mental causation, though the results apply more broadly.

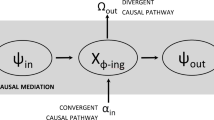

In greater detail, Lei Zhong’s autonomy solution appeals to what he calls the “dual condition conception of causation” (Zhong 2014, 342), which is rooted in Chris Woodward’s interventionist model of causation and bares affinity with the difference-making model of causation presented by List and Menzies (2009). According to Zhong’s view, X is a cause of Y if the following two conditions are true: (A) If an intervention that sets X = xp were to occur (while all other relevant variables in the causal graph are fixed), then Y = yp; (B) If an intervention that sets X = xa were to occur (while all other relevant variables in the causal graph are fixed), then Y = ya (Zhong 2014, 344). The variable xp in (A) stands for x being present, so (A) roughly states that if an intervention that makes x present were to occur, then y is present. As such, (A) is called the Presence Condition (Zhong 2014, 345). The variable xa in (B) stands for x being absent, so (B) roughly states that if an intervention that makes x absent were to occur, then y is absent. As such (B) is called the Absence Condition (Zhong 2014, 345). Thus, these counterfactuals adequately approximate Zhong’s Absence Condition and Presence Condition, as applied to mental causation (cp. Zhong 2014, 356). It is worth noting that Zhong has recently modified his position. He now rejects the principle of physical causal completeness, thereby allowing him to claim that mental causes bring about physical effects without violating causal exclusion (Zhong 2019). Tuomas Pernu appeals to a modified version of the counterfactual model of causation, according to which X is a cause of Y if the following two counterfactuals are true: (A) Had X occurred, then Y would have occurred (X □→ Y); (B) Had X not occurred, then Y would not have occurred (~X □→ ~Y). The traditional counterfactual model, as popularized by David Lewis (1973), takes (A) to be automatically true, since the nearest possible world where X is true is the actual world in which X and Y occur, so Pernu’s (B) is of central concern. Pernu does not follow this strongly centred view, according to which there is one nearest possible world which is the actual world. Rather, he endorses a weakly centred view, according to which there may be many nearest possible worlds, some of which are not the actual world (Pernu 2016, 1037–1040). This model, which resembles the difference-making model of causation endorsed by Christian List and Peter Menzies (List and Menzies 2009, 483–484), does not result in the automatic truth of (A). Thus, both (A) and (B) must be established as true in order to determine causation. Thus, these are the germane counterfactuals to discern mental causation.

Establishing what the nearest possible worlds are requires a similarity metric for possible worlds. Neither Zhong nor Pernu offer explicit details about their similarity metric. The following details are available, however. Pernu operates within Lewis’ counterfactual model of causation, while only diverging with Lewis’ strong centring view that the nearest possible world is the actual world. Lewis’s similarity metric procedes as follows: the nearest worlds (besides the actual world) are the worlds where a local violation of law altars a particular fact, further worlds are worlds with larger divergences of particular facts across space and time, and the furthest worlds are worlds with widespread violation of law (Lewis 1986, 47). Zhong also rejects Lewis’s strong centring view that the nearest world is the actual world, so m □→ p* does not come out as automatically true for Zhong either (Zhong 2014, 345). Beyond this, while Zhong operates within Lewis’ counterfactual model in other papers (Zhong 2011), he operates within Woodward’s interventionist model in the target paper. Woodward’s interventionist model has both similarities and differences with Lewis’ similarity metric of possible worlds (Woodward 2003, 133–145). For Woodward, an intervention that breaks a causal chain is similar to a local violation of law that altars a particular fact. So, in some ways Woodward’s model is extremely strict in following Lewis’s similarity metric. That is, on interventionism, it is local violations of law that occur, even if these local violations of law generate large divergences of particular facts across spacetime, or conjoin to form a widespread violation of law.

Pernu and Zhong combine the absence of p* with the presence of some other realizer p2*. This is controversial. First, some operating within a counterfactual model argue that the absence of p* should not be combined with the presence of some other realizer p2*, but should be a clean excision without replacement by p2* (Harbecke 2014, 366; Bennett 2003, 482). On this excision model, the absence of p*, without replacement by another realizer, amounts to the absence of m* as well, by supervenience. This result would damage Pernu’s and Zhong’s claim that the presence of m also makes m* present, thereby calling mental-to-mental causation into doubt. This is a problem within the interventionist model that Zhong deploys as well. Zhong’s two conditions on causation both require holding other variables fixed (Woodward 2008, 240), yet his solution sets a third variable p2* from absent to present, which is not to hold other variables fixed (cp. McDonnell 2017, 1467). That being said, I grant Pernu and Zhong the view that the presence of m may lead to the presence of m* being realized by p2*.

In this quotation, as well as several others, I modify the names of the variables to retain consistency throughout this paper.

Indeed, not only does Kim use Edwards’s Dictum to exclude direct mental-to-mental causation, but he then uses Edwards’s Dictum to prove that any instance of mental-to-mental causation must proceed via downward causation. According to Edwards’s Dictum, the only way for m* to occur is for p* to determine m*, so the only way m can cause m* is for m to cause p* to determine m*. At first glance, this seems odd—Kim says mental properties cannot have mental or physical causes (by Edwards’s Dictum), but mental properties can cause mental or physical effects (by Downward Causation). The oddity is quickly dissolved, however, as Kim only introduces the possibility of m downwardly causing p* in order to reject this possibility since p is the sufficient cause of p*. As discussed in Sect. 1, it is this downward causation requirement that immediately leads to physical effect overdetermination, so Kim uses Edwards’s Dictum to generate multiple problems for mental causation.

Granted Monique’s mere bodily reflex may be qualitatively distinct from Monique’s act of kicking—Monique’s reflex may be more twitchy, spasmatic, and may contain slightly different muscular contractions than Monique’s act of kicking. These differing bodily movements may occur because they were caused by slightly different neural processes. It is possible, however, to imagine a neuroscientist stimulating the exact neural processes responsible for causing Monique’s act of kicking, leading to a qualitatively the same bodily movement as Monique’s act of kicking, though this bodily movement is not Monique’s act of kicking, since it was caused by the neuroscientist’s stimulation of her brain.

For recent book-length defenses of the Causal Theory of Action, consult Bishop (1989), Brand (1984) and Mele (1992). The causal theory of action faces numerous criticisms and issues, but it lies outside the scope of this paper to substantially address these issues. For a recent collection of essays discussing the merits, demerits, and issues surrounding the causal theory of action, see Aguilar and Buckareff (2010).

It is possible to argue that Supervenience is the view that both p* □→ m* and m* □→ ∪p* are true. While Supervenience may entail the truth of these counterfactuals, this latter counterfactual does not fully capture the supervenience claim that m* is dependent upon, because determined by, some p*. Hence, I substitute this latter counterfactual for counterfactual (6). Nothing of substance below hinges on this substitution.

Kim sidesteps these issues by abandoning Irreducibility, which renders moot the discussion on the viability of Upward Causation and Downward Causation, and allows for only horizontal causation.

References

Aguilar, J., & Buckareff, A. (2010). Causing human actions. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Anscombe, E. (1957). Intention. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Baker, L. (2012). What we do. In J. Bransen & S. Cuypers (Eds.), Human action, deliberation and causation (pp. 249–270). Berlin: Springer.

Bennett, K. (2003). Why the exclusion problem seems intractable, and how, just maybe, to tract it. Noûs, 37, 471–497.

Bishop, J. (1989). Natural agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bishop, J. (2010). Skepticism about natural agency and the causal theory of action. In J. Aguilar & A. Buckareff (Eds.), Causing human actions (pp. 69–84). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bjerring, J. (2014). On Counterpossibles. Philosophical Studies, 168, 327–353.

Bogardus, T. (2013). Undefeated Dualism. Philosophical Studies, 165(2), 445–466.

Brand, M. (1984). Intenting and acting. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Brogaard, B., & Salerno, J. (2013). Remarks on Counterpossibles. Synthese, 190(4), 639–660.

Burge, T. (1993). Mind-body causation and explanatory practice. In J. Heil & A. Mele (Eds.), Mental causation (pp. 99–117). Oxford: Clarendon.

Burge, T. (2007). Foundations of mind: Philosophical essays (Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, N. (2015). Does same level causation entail downward causation. Abstracta, 8(2), 53–66.

Cavedon-Taylor, D. (2008). Still epiphenominal qualia. Philosophia, 37(1), 105–107.

Chalmers, D. (1996). The conscious mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

Craver, C., & Bechtel, W. (2007). Top-down causation without top-down causes. Biology and Philosophy, 22, 547–563.

Crisp, T., & Warfield, T. (2001). Kim’s master argument. Noûs, 35, 304–316.

Davidson, D. (1963). Actions, reasons and causes. Journal of Philosophy, 60, 685–700.

Davidson, D. (1980). “Agency”, actions and events. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Davidson, D. (1987). Knowing one’s own mind. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association, 60(3), 441–458.

Davidson, D. (2004). Problems in the explanation of action. In M. Cavell (Ed.), Problems of rationality (pp. 101–116). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Engelhardt, J. (2015). What is the exclusion problem? Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 96, 205–232.

Engelhardt, J. (2017). Mental causation is not just downward causation. Ratio, 30(1), 31–46.

Fodor, J. (1974). Special sciences, or the disunity of science as a working hypothesis. Synthese, 28, 77–115.

Fodor, J. (1989). Making mind matter more. Philosophical Topics, 17(1), 59–79.

Gibbons, J. (2006). Mental causation without downward causation. Philosophical Review, 115, 79–103.

Ginet, C. (1990). On action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harbecke, J. (2014). Counterfactual causation and mental causation. Philosophia, 42(2), 363–385.

Holmes, O. (1963). The common law. Boston: Little, Brown.

Honderich, T. (1982). The argument for anomalous monism. Analysis, 42, 59–64.

Horgan, T. (1989). Mental quausation. Philosophical Perspectives, 3, 47–76.

Hume, D. (1888). A treatise of human nature, L. Selby Bigge (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyman, J. (2015). Action, knowledge and will. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, F. (1982). Epiphenomenal qualia. The Philosophical Quarterly, 32(127), 127–136.

Jacob, P. (2002). Some problems for reductive physicalism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 65, 648–654.

Kim, J. (1984). Epiphenomenal and supervenient causation. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 9, 257–270.

Kim, J. (1995). Mental causation in Searle’s biological naturalism. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 55, 189–194.

Kim, J. (1998). Mind in a physical world. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kim, J. (1999). Making sense of emergence. Philosophical Studies, 95, 3–36.

Kim, J. (2005). Physicalism, or something near enough. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kim, J. (2009). Mental causation. In B. McLaughlin, A. Beckermann, & S. Walter (Eds.), Oxford handbook of philosophy of mind (pp. 29–52). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, D. (1973). Causality. The Journal of Philosophy, 70, 556–567.

Lewis, D. (1986). Philosophical papers (Vol. II). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

List, C., & Menzies, P. (2009). Nonreductive physicalism and the limits of the exclusion principle. Journal of Philosophy, 106(9), 475–502.

Loewer, B. (2015). Mental causation: The free lunch. In T. Horgan, M. Sabates, & D. Sosa (Eds.), Qualia and mental causation in a physical world (pp. 40–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lowe, E. (1993). The causal autonomy of the mental. Mind, 102, 629–644.

Lowe, E. (2006). Non-Cartesian substance dualism and the problem of mental causation. Erkenntnis, 65(1), 5–23.

Marras, A. (1998). Kim’s principle of explanatory exclusion. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 76, 439–451.

Marras, A. (2007). Kim’s supervenience argument and nonreductive physicalism. Erkenntnis, 66, 305–327.

McDonnell, N. (2017). Causal exclusion and the limits of proportionality. Philosophical Studies, 174(6), 1459–1474.

McGinn, C. (1989). Mental content. Oxford: Blackwell.

Melden, A. (1964). Action. In D. Gustafson (Ed.), Essays in philosophical psychology. New York: Doubleday.

Mele, A. (1992). Springs of action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mele, A. (1997). Agency and mental action. Philosophical Perspectives, 11(S), 231–249.

Melnyk, A. (2003). Physicalist manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Montero, B. (2003). Varieties of causal closure. In S. Walter & H. Hackmann (Eds.), Physicalism and mental causation (pp. 173–187). Imprint Academic: Exeter.

Moore, D. (2013). Counterfactuals, autonomy and downward causation. Philosophia, 41, 831–839.

Nagasawa, Y. (2010). The knowledge argument and epiphenomenalism. Erkenntnis, 72, 37–56.

Papineau, D. (2001). The rise of physicalism. In C. Gillett & B. Loewer (Eds.), Physicalism and its discontents (pp. 3–36). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pernu, T. (2016). Causal exclusion and downward counterfactuals. Erkenntnis, 81(5), 1031–1049.

Putnam, H. (1967). Psychological predicates. In W. Capitan & D. Merrill (Eds.), Art, mind and religion (pp. 37–48). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Schlosser, M. (2009). Nonreductive physicalism, mental causation and the nature of actions. In Alexander Hieke & Hannes Leitgeb (Eds.), Reduction: Between the mind and the brain (pp. 73–90). Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Searle, J. (1983). Intentionality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shepherd, J. (2017). The experience of acting and the structure of consciousness. Journal of Philosophy, 114(8), 422–448.

Silberstein, M. (2001). Converging on emergence. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8, 61–98.

Smith, M. (2010). The standard story of action: An exchange. In J. Aguilar & A. Buckareff (Eds.), Causing human actions (pp. 45–56). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sosa, E. (1984). Mind–body interaction and supervenient causation. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 9, 271–281.

Taylor, R. (1960). Action and purpose. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Thomasson, A. (1998). A nonreductivist solution to mental causation. Philosophical Studies, 89, 181–195.

Tuomela, R. (1998). A defense of mental causation. Philosophical Studies, 90(1), 1–34.

Walter, S. (2008). The supervenience argument, overdetermination, and causal drainage. Philosophical Psychology, 21, 673–696.

Woodward, J. (2003). Making things happen. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woodward, J. (2008). Mental causation and neural mechanisms. In J. Hohwy & J. Kallestrup (Eds.), Being reduced: New essays on reduction, explanation, and causation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Zhong, L. (2011). Can counterfactuals solve the exclusion problem? Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 83(1), 129–147.

Zhong, L. (2014). Sophisticated exclusion and sophisticated causation. Journal of Philosophy, 111(7), 341–360.

Zhong, L. (2019). Taking emergentism seriously. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048402.2019.1589547.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous referees at this journal for their valuable comments and suggestions that greatly improved this paper. I would also like to thank the audience members and commentators at the 2018 Western Canadian Philosophical Association Meeting, the 2019 Canadian Philosophical Association Meeting, and the 2019 Central American Philosophical Association Meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, D. Mental Causation, Autonomy and Action Theory. Erkenn 87, 53–73 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-019-00184-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10670-019-00184-5