Abstract

Studies indicate that organizational capability is a key factor in operational performance, and that both sensing and analytics capabilities have a significant influence on operational performance. This study develops a framework to examine the impact of organizational capability on operational performance, with a specific focus on the implementation of sensing and analytics capabilities. We combine strategic fit theory, the dynamic capability view, and the resource-based view to examine how micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) strategically integrate a data-driven culture (DDC) with their organizational capabilities to enhance operational performance. We carry out empirical research to investigate whether a DDC moderates the influence of organizational capability on operational performance. Structural equation modeling of survey data from 149 MSMEs reveals that both sensing and analytics capabilities have a positive impact on operational performance. The results also suggest that a DDC positively moderates the influence of organizational capability on operational performance. We discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of our findings, the limitations of the study, and opportunities for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) make up over 90% of all firms across the world.Footnote 1 MSMEs in the manufacturing industry are responsible for a large proportion of global pollution and resource consumption. The definition of MSMEs varies across continents relative to the size of the domestic economy. In this study, we follow the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and define MSMEs as firms with a maximum of 249 employees, which includes micro (1–9), small (10–49) and medium (50–249) enterprises (United Nations Report, 2020, p. 4).

Industry 4.0, big data analysis, optimization, logistics excellence, automation, digital transformation, and the circular economy have become buzzwords in modern economies. Industry 4.0 is changing the design and functioning of operations and supply chains. For example, block chain and the internet of things (IoT) now play a vital role in improving supply chain transparency and traceability. However, few empirical studies have explored the prospects and impact of Industry 4.0 on operations (Frederico et al., 2019). Operations management, which in the past was generally viewed as a horizontal function, has now become established as a form of vertical management with multiple branches (Gupta et al., 2013).

Modern operations managers must have insight into the alignment of operational strategies with organizational goals. Supply chain experts and business analysts must be able to predict the network design, quality norms, and impact of technology on business operations (Chae et al., 2014). Analytics now plays a vital role in operations management and decision-making (Choi et al., 2018), and the integration of operations and analytics optimizes processes. Analytics is also important to the circular economy, sustainable operations, and risk management (Mani et al., 2017).

In develo** countries like China, one of the main issues for MSMEs is non-standardized output due to problems with the production process, conventional machinery, limited financial support, and a shortage of skilled labor, all of which lead to comparatively greater waste generation in terms of repairs and rejections, resulting in a loss of goodwill and profits (Gupta et al., 2019). The application of analytics and sensing capabilities can help MSMEs detect potential errors early, evaluate the causes of defects, and predict the number of reworks required to enhance operational performance (Sariyer et al., 2021).

This study has two objectives. The first is to examine the impact of organizational capability on operational performance, focusing on the implementation of analytics and sensing capabilities to enhance operational performance. The second objective is to investigate whether a data-driven culture (DDC) moderates the influence of organizational capability on operational performance. Accordingly, we address the following research questions:

Research question 1. How does organizational capability influence operational performance?

Research question 2. How does a DDC moderate the influence of organizational capability on operational performance?

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the theory and hypotheses and develops the research model. Section 3 outlines the research design and data collection methods. Section 4 presents the data analysis and results. Finally, Sect. 5 discusses the theoretical contributions, managerial implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2 Theory and hypotheses

2.1 MSMEs

MSMEs have helped accelerate economic development in Asia (Kamble et al., 2020). MSMEs face various challenges because of their constrained resources. In addition, many lack up-to-date technology and, as a result, either faced supply chain bottlenecks or collapsed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bag et al., 2021; Modgil et al., 2021). Therefore, sustainability is a critical concern, especially for MSMEs that are highly vulnerable to uncertainty and risk (Behi et al., 2022). MSMEs urgently need to shift to digital technologies to survive. However, their inability to effectively and quickly migrate to the newest business models and technologies from traditional models and technologies makes it challenging for MSMEs to adopt digital technologies (Ritter & Pedersen, 2020). MSMEs must also build resilience by enhancing their ability to recognize market opportunities (Khurana et al., 2022). Analytics capability can help firms do this by allowing them to analyze large sets of data from diverse sources. Analytics capabilities allow MSMEs to control heterogeneous and vast data sets and assess the states of external markets and business units (Rialti et al., 2019). Analytics capabilities also allow MSMEs to collect data from social media platforms to analyze customer sentiments and behavior to help create new revenue streams.

2.2 Operational performance

Operational performance refers to “a firm’s operational efficiency, which can help explain the firm’s competitiveness and profitability in the market” (Hong et al., 2019, p. 228). Develo** a substantial predictive capability through big data analytics can help an organization to reap the greatest possible advantages, leading to higher operational performance (Gupta et al., 2020). Previous studies typically measure operations management using time, flexibility, quality, and cost (Neely et al., 1995). In this study, we apply the operational performance measures of Liu et al. (2016) to evaluate the operational benefits of the fit of a firm’s resources to its environment. These measures comprise seven items that collectively assess the effects of sensing and analytics capabilities on process-related performance. They are commonly used to assess IT-enabled competitive advantages in empirical studies of information systems and operations management that apply the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Flynn et al., 2010; Rai et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2011).

Operational performance can be assessed using a variety of methods and measures. However, we focus specifically on a previously studied perspective: organizational capability. The main focus of organizational capability is identifying the critical determinants of a company’s competitive advantage and performance (Krasnikov & Jayachandran, 2008).

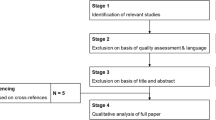

"Appendix A" summarizes the main studies on the influence of organizational capability on business performance published in the past ten years. The reviewed works are classified by type of study, theory applied, author, and year, and the main findings of each study are listed. We find extensive use of the RBV (12 of 22 articles) and the dynamic capability view (DCV; 9 of 22 articles). "Appendix B" lists the articles included in our literature review.

2.3 Organizational capability

The focus of the RBV is the internal operations of a firm and its bundle of resources (Priem & Butler, 2001). This widely supported view (Barney, 2001) posits that firms with valuable, non-substitutable, and scarce resources can obtain a sustainable competitive advantage. Organizational capability can be considered a resource (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998), and researchers have found that organizational capability helps managers select meaningful organizational outputs (Von Alan et al., 2004; Winter, 2000). Organizational capability can be described as a firm’s ability to transform inputs into outputs to create value (Chatterjee et al., 2015), and is a critical determinant of a company’s performance and competitive advantage (Krasnikov & Jayachandran, 2008). In the hierarchy of capabilities conceptualized by Grant (1996), specialized knowledge comprises task-specific and activity-related capabilities at the lowest level. These capabilities are then integrated at the middle level into broad functional capabilities, such as R&D and manufacturing. At the highest level are cross-functional capabilities, such as innovation (Peng et al., 2008), collaboration (Allred et al., 2011), sensing capabilities (Vanpoucke et al., 2014), and analytics capabilities (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). Studies indicate that sensing capabilities (Ngo et al., 2019) and analytics capabilities (Dubey et al., 2021; Fosso Wamba et al., 2020) are exerting an increasingly significant influence on business performance. However, the literature on the effect of sensing and analytics capabilities on operational performance is sparse, particularly in relation to a DDC in MSMEs. Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by offering a research model of the relationship between sensing and analytics capabilities and operational performance, and by illustrating the moderating facets of a DDC.

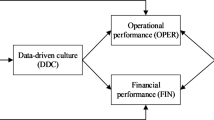

Our proposed conceptual model (see Fig. 1) is based on the RBV and the idea that superior operational performance results from the best use of the sensing and analytics capabilities an organization possesses (Barney, 1986, 1991). Studies also suggest that a DDC plays a key role in sha** a firm’s business analytics and competitive advantage (Chatterjee et al., 2021). Thus, our model incorporates a DDC to investigate its moderating effect on organizational capability and operational performance. Obtaining a strategic fit in a dynamic environment requires a DDC that allows the organization to accurately assess environmental changes, formulate responses, and reconfigure its internal resources. This is also consistent with the RBV of the firm (Barney, 1986, 1991, 2001) and is in line with the DCV of an organization’s ability to determine the resources available to it and apply them effectively in a dynamic environment (e.g., Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Teece et al., 1997).

2.3.1 Analytics capabilities

According to Wu et al. (2020), analytics capabilities refer to the ability to transform, analyze, and process data into useful information to support decision-making, provide useful insights, and reveal patterns that could be improved by digitization and artificial intelligence. Srinivasan and Swink (2018) further extended the definition of analytics capabilities, describing them as organizational facilities that encompass tools, processes, and techniques that enable an organization to process, visualize, analyze, and organize data to produce managerial insights that enable data-driven operational decision-making, operational planning, and execution. Analytics capabilities also enable firms to improve their information processing capabilities to collect data from different sources and analyze them to obtain managerial insights (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018). Companies combine these processes and tools to integrate, decompose, and combine information. Many firms are investing in different types of analytics capabilities to increase their operational performance, such as data analytics (Sariyer et al., 2021), business analytics (Krishnamoorthi & Mathew, 2018), information analytics (Park & Mithas, 2020), and big data analytics (Dubey et al., 2021). Analytics capabilities also enable firms to evaluate operational alternatives when there are changes in demand or supply shortages, and to develop resources and cost-saving measures to reduce the imbalance between supply and demand (Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Analytics capabilities have a direct positive effect on operational performance.

2.3.2 Sensing capabilities

A firm’s sensing capabilities refer to its ability to assess, develop, and identify technological opportunities that meet customers’ needs and new business opportunities (Fosso Wamba et al., 2020). They also refer to a firm’s ability to learn from the market environment and then take action based on its newly acquired knowledge (Fosso Wamba et al., 2020). Sensing capabilities include the generation and dissemination of market intelligence and ability to react to it (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993) to improve operational performance (Shin et al., 2015). Sensing capabilities are rooted in market development and organizational information processing activities such as evaluating, filtering, interpreting, and scanning information (Mu & Di Benedetto, 2011). These processing activities apply logic in volatile, unpredictable, and complex market environments to help firms perceive market opportunities and changes before they materialize (Day, 2011). For instance, American Airlines uses a decision-support system that works with its reservation system to enhance its sensing capabilities (Chi et al., 2010). Effective sensing capabilities yield nuanced, accurate, and diverse information that supports an understanding of the opportunities and threats facing a firm (Ballesteros et al., 2017). Such capabilities help keep a firm vigilant and alert to opportunities and market trends. Sensing capabilities are increased by deploying IT to transform informational resources into knowledge assets. Business intelligence systems can help continuously improve operational performance by discerning and receiving accurate, timely, and relevant information and data and then transforming and analyzing it to create new knowledge (Chen & Lin, 2021). For example, firms with superior IT-enabled sensing capabilities are able to adjust their internal operations in response to potential shifts in the business environment by closely monitoring their competitors’ movements and customer feedback to inform appropriate operations management decisions (Mikalef & Pateli, 2017). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

Sensing capabilities have a direct positive effect on operational performance.

2.4 DDC

Mikalef and Krogstie (2020, p. 262) suggest that a DDC is “a key factor in determining overall success and the alignment with organizational strategy.” A DDC is defined (Kiron et al., 2013, p. 18) as “a pattern of behavior and practices by a group of people who share a belief that having, understanding, and using certain kinds of data and information plays a crucial role in the success of their organizations.” Strategic fit theory suggests that develo** organizational capability through strategic integration results in a competitive advantage and better performance (Kristianto et al., 2011). Performance can also be improved by establishing a good fit between a firm’s environment and its resources (Kashan & Mohannak, 2017). Firms should try to match their resource deployment to their strategic requirements (Swink et al., 2005). A DDC combines organizational factors such as business processes, structures, regulation, and strategy to facilitate the application of business analytics (Cao & Duan, 2015). A firm with a DDC treats data as an intangible asset that has value to the firm (Kiron & Shockley, 2011), and creates an environment for management to make decisions that result in superior operational performance and efficiency and thus enhance competitiveness.

The RBV states that firms need to develop capabilities to gain a competitive advantage and overcome difficulties. However, this view fails to appropriately delineate the capabilities needed in dynamic environments. Further, it gives no clear explanation of why and how firms gain a competitive advantage in uncertain environments. The DCV fills this gap by promoting the organization with appropriate resources and capabilities to deal with situation-specific changes (Barney, 1991; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Wernerfelt, 1984), thereby addressing contingencies. Moreover, it suggests that firms in dynamic environments should focus on improving their capabilities rather than merely exploiting specific resources to gain a competitive advantage (Teece et al., 1997). A DDC is a critical intangible resource (Zhu et al., 2021) that can be referred as “the extent to which organizational members (including top-level executives, middle managers, and low-level employees) make decisions based on the insights extracted from data” (Gupta & George, 2016, p. 1053). It is associated with assumptions, beliefs, and values that lead to organizational success (Chatterjee et al., 2021). In addition, a DDC helps companies improve performance by using data-based insights to take appropriate decisions. Firms can create a DDC by leveraging business analytics to gain a competitive advantage (Chatterjee et al., 2021). The three main types of analytics capabilities that improve operational performance are intangible resources, tangible resources, and human skills and knowledge. As an intangible resource (Zhu et al., 2021), a DDC may be an important variable moderating the relationship between analytics and sensing capabilities and operational performance. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are almost no reported studies that explore DDC as a moderator of this relationship. We therefore propose the following hypotheses:

H3a

A DDC has a moderating effect on the relationship between analytics capabilities and operational performance.

H3b

A DDC has a moderating effect on the relationship between sensing capabilities and operational performance.

2.5 Control variables

We control for firm size because this is correlated with operational performance (Psillaki et al., 2010). Small and micro firms face more challenges and need more support than medium or large firms due to their limited resources, which may influence operational performance (Lwesya et al., 2021). We also control for firm age, as years of business experience can also influence operational performance (Hsieh et al., 2010; Lwesya et al., 2021).

3 Research methodology

Our conceptual framework is founded on theoretical observations from the literature. We then examined the research model in a quantitative study (Weerawardena et al., 2015). The data were collected using a self-report survey instrument that was carefully developed using guidelines and exemplars in the operational management and information systems literature, for example, Srinivasan and Swink (2018) and Pavlou and El Sawy (2011).

3.1 Research design

We gathered our survey data exclusively from the food industry for several reasons. The world population is expected to reach more than nine billion by 2050, increasing the burden on world food production systems (Godfray et al., 2010). Traditionally, the food industry is considered slow-growing and mature compared with other industries (Santoro et al., 2017). The industry faces various challenges, including greater competition and disruptive technologies such as big data and the internet of things (Ferraris et al., 2020). For hundreds of years, information has been vital to the food industry (Godfray et al., 2010), which has long been recognized as a data-driven industry (Serazetdinova et al., 2019). Information and data collected from competitors and consumers allow the industry to determine current and future production trends (Chapman et al., 2021).

We first interviewed six managers in the industry to check their understanding of the items in our questionnaire. We then clarified and reformulated certain items to make them more understandable. Finally, this instrument was used to collect survey data from supply chain managers in the food industry via online questionnaires (Lee & ** their firm’s sensing capabilities. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic caused various difficulties for MSMEs, such as order cancellations, constrained cash flows, and a lack of organization-level communication. Overcoming these issues required the ability to sense business opportunities at the organizational level, to understand what was happening within organizations, and to learn from both external and internal sources (Khurana et al., 2022). Sensing capabilities help MSMEs retain clients and attract new customers by highlighting customers’ needs, allowing firms to modify products to match changing customer requirements and preferences. For example, analyzing the text and sentiment in customers’ social media posts can help identify customer preferences, from which firms can identify new opportunities (Huang et al., 2020).

Fourth, MSMEs need to develop analytics capabilities because of their resource constraints (Shafiq et al., 2020). For example, MSMEs need to synergistically and strategically deploy limited resources for both operations and business development. MSMEs can more accurately match their resources to potential business opportunities if they have strong big data analytics capabilities (Mikalef et al., 2020). Big data analytics capabilities enable MSMEs to use data-driven decision-making to exploit, combine, and coordinate their constrained resources to avoid environmental or external market threats and take advantage of valuable opportunities to grow (Zheng et al., 2022).

5.4 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. As we investigated the food supply chain in Shanghai (China), our findings may not be generalizable to other industries or countries. In addition, we only studied the influence of cross-functional capabilities (i.e., analytics and sensing capabilities) on operational performance. However, capabilities in specific areas such as R&D and manufacturing also can affect performance (Nystrom et al., 2002). The data were collected in China, and although it is an important food supply chain, the results may not be fully generalizable to other Asian or Western countries. We acknowledge these limitations, which future studies could investigate further.

Furthermore, the conceptual framework and research model in this study focus on a DDC in the supply chain context, but several other domains deserve investigation in future studies. For example, fruitful findings could be obtained by exploring a DDC in other settings, industries, and types of organizations. Such research would also help to validate the framework and research model presented here and enhance its generalizability. The managerial and theoretical development of a DDC is also a rich topic for future studies; for example, it would be interesting to study the moderating role of a DDC in the relationship between data-driven innovations and firm performance. We expect new approaches to the topic to emerge from further critical reviews, examinations, and investigations.

6 Conclusions

We obtained evidence through a survey study of 149 MSMEs in China’s food industry on the influence of sensing and analytics capabilities on operational performance and how a DDC moderates that influence. Our findings confirm our hypothesis that sensing and analytics capabilities directly improve operational performance. We also found that a DDC positively moderates the influence of sensing and analytics capabilities on operational performance.

This study makes a valuable contribution to research on sensing and analytics capabilities and DDCs. Our findings also provide researchers and practitioners with important insights into how operational performance can be improved by sensing and analytics capabilities, and the moderating role of a DDC in the relationship between organizational capabilities and operational performance.

References

Abbasi, A., Sarker, S., & Chiang, R. H. (2016). Big data research in information systems: Toward an inclusive research agenda. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(2), i–xxxii.

Allred, C. R., Fawcett, S. E., Wallin, C., & Magnan, G. M. (2011). A dynamic collaboration capability as a source of competitive advantage. Decision Sciences, 42(1), 129–161.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Bag, S., Dhamija, P., Luthra, S., & Huisingh, D. (2021). How big data analytics can help manufacturing companies strengthen supply chain resilience in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Logistics Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2021-0095

Bai, L., Ma, C., Gong, S., & Yang, Y. (2007). Food safety assurance systems in China. Food Control, 18(5), 480–484.

Ballesteros, L., Useem, M., & Wry, T. (2017). Masters of disasters? An empirical analysis of how societies benefit from corporate disaster aid. Academy of Management Journal, 60(5), 1682–1708.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32(10), 1231–1241.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120.

Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56.

Bassellier, G., & Benbasat, I. (2004). Business competence of information technology professionals: Conceptual development and influence on IT-business partnerships. MIS Quarterly, 673–694.

Behl, A., Gaur, J., Pereira, V., Yadav, R., & Laker, B. (2022). Role of big data analytics capabilities to improve sustainable competitive advantage of MSME service firms during COVID-19–A multi-theoretical approach. Journal of Business Research, 148, 378–389.

Bumblauskas, D., Nold, H., Bumblauskas, P., & Igou, A. (2017). Big data analytics: Transforming data to action. Business Process Management Journal., 23(3), 703–720.

Cao, G., & Duan, Y. (2015). The Affordances of Business Analytics for Strategic Decision-Making and Their Impact on Organisational Performance. In PACIS (p. 255).

Chae, B., Olson, D., & Sheu, C. (2014). The impact of supply chain analytics on operational performance: A resource-based view. International Journal of Production Research, 52(16), 4695–4710.

Chapman, J., Power, A., Netzel, M. E., Sultanbawa, Y., Smyth, H. E., Truong, V. K., & Cozzolino, D. (2020). Challenges and opportunities of the fourth revolution: A brief insight into the future of food. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 62(10), 2845–2853.

Chatterjee, S., Moody, G., Lowry, P. B., Chakraborty, S., & Hardin, A. (2015). Strategic relevance of organizational virtues enabled by information technology in organizational innovation. Journal of Management Information Systems, 32(3), 158–196.

Chatterjee, S., Chaudhuri, R., & Vrontis, D. (2021). Does data-driven culture impact innovation and performance of a firm? An empirical examination. Annals of Operations Research, 1–26.

Chen, Y., & Lin, Z. (2021). Business intelligence capabilities and firm performance: A study in China. International Journal of Information Management, 57(102232), 1–15.

Chi, L., Ravichandran, T., & Andrevski, G. (2010). Information technology, network structure, and competitive action. Information Systems Research, 21(3), 543–570.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336.

Choi, T. M., Wallace, S. W., & Wang, Y. (2018). Big data analytics in operations management. Production and Operations Management, 27(10), 1868–1883.

Day, G. S. (2011). Closing the marketing capabilities gap. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 183–195.

Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., Childe, S. J., Fosso Wamba, S., Roubaud, D., & Foropon, C. (2021). Empirical investigation of data analytics capability and organizational flexibility as complements to supply chain resilience. International Journal of Production Research, 59(1), 110–128.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they?. Strategic Management Journal, 1105–1121

Ferraris, A., Vrontis, D., Belyaeva, Z., De Bernardi, P., & Ozek, H. (2020). Innovation within the food companies: How creative partnerships may conduct to better performances? British Food Journal, 123(1), 143–158.

Flynn, B. B., Huo, B., & Zhao, X. (2010). The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. Journal of Operations Management, 28(1), 58–71.

Fosso Wamba, S., Queiroz, M. M., Wu, L., & Sivarajah, U. (2020). Big data analytics-enabled sensing capability and organizational outcomes: assessing the mediating effects of business analytics culture. Annals of Operations Research, 1–20.

Frederico, G. F., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Anosike, A., & Kumar, V. (2019). Supply Chain 4.0: concepts, maturity and research agenda. Supply Chain Management: an International Journal, 25(2), 262–282.

Gefen, D., Straub, D., & Boudreau, M. C. (2000). Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 7.

Godfray, H. C. J., Beddington, J. R., Crute, I. R., Haddad, L., Lawrence, D., Muir, J. F., Pretty, J., Robinson, S., Thomas, S. M., & Toulmin, C. (2010). Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science, 327(5967), 812–818.

Grant, R. M. (1996). Prospering in dynamically-competitive environments: Organizational capability as knowledge integration. Organization Science, 7(4), 375–387.

Gupta, S., Drave, V. A., Dwivedi, Y. K., Baabdullah, A. M., & Ismagilova, E. (2020). Achieving superior organizational performance via big data predictive analytics: A dynamic capability view. Industrial Marketing Management, 90, 581–592.

Gupta, A., Sharma, P., Jain, A., Xue, H., Malik, S. C., & Jha, P. C. (2019). An integrated DEMATEL Six Sigma hybrid framework for manufacturing process improvement. Annals of Operations Research, 1–41.

Gupta, M., & George, J. F. (2016). Toward the development of a big data analytics capability. Information and Management, 53(8), 1049–1064.

Gupta, P., Seetharaman, A., & Raj, J. R. (2013). The usage and adoption of cloud computing by small and medium businesses. International Journal of Information Management, 33(5), 861–874.

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press.

Harrison, D. A., McLaughlin, M. E., & Coalter, T. M. (1996). Context, cognition, and common method variance: Psychometric and verbal protocol evidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(3), 246–261.

Hong, J., Guo, P., Deng, H., & Quan, Y. (2021). The adoption of supply chain service platforms for organizational performance: Evidences from Chinese catering organizations. International Journal of Production Economics, 237, 108147.

Hong, J., Liao, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yu, Z. (2019). The effect of supply chain quality management practices and capabilities on operational and innovation performance: Evidence from Chinese manufacturers. International Journal of Production Economics, 212, 227–235.

Hsieh, T. J., Yeh, R. S., & Chen, Y. J. (2010). Business group characteristics and affiliated firm innovation: The case of Taiwan. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(4), 560–570.

Huang, S., Potter, A., & Eyers, D. (2020). Social media in operations and supply chain management: State-of-the-Art and research directions. International Journal of Production Research, 58(6), 1893–1925.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (1993). Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 53–70.

Jen, J. J. (2018). Global challenges of food safety for China. Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering, 5(3), 291–293.

Kamble, S. S., Gunasekaran, A., Ghadge, A., & Raut, R. (2020). A performance measurement system for industry 4.0 enabled smart manufacturing system in SMMEs-A review and empirical investigation. International Journal of Production Economics, 229, 107853, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107853

Kashan, A. J., & Mohannak, K. (2017). Integrating the content and process of capability development: Lessons from theoretical and methodological developments. Journal of Management and Organization, 25(5), 748–763.

Khurana, I., Dutta, D. K., & Ghura, A. S. (2022). SMEs and digital transformation during a crisis: The emergence of resilience as a second-order dynamic capability in an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Journal of Business Research, 150, 623–641.

Kiron, D., & Shockley, R. (2011). Creating business value with analytics. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(1), 57–63.

Kiron, D., Ferguson, R. B., & Prentice, P. K. (2013). From value to vision: Reimagining the possible with data analytics. MIT Sloan Management Review, 54(3), 1–19.

Kiron, D., Prentice, P. K., & Ferguson, R. B. (2014). The analytics mandate. MIT Sloan Management Review, 55(4), 1–21.

Krasnikov, A., & Jayachandran, S. (2008). The relative impact of marketing, research-and development, and operations capabilities on firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 72(4), 1–11.

Krishnamoorthi, S., & Mathew, S. K. (2018). Business analytics and business value: A comparative case study. Information and Management, 55(5), 643–666.

Kristianto, Y., Helo, P., & Takala, J. (2011). Manufacturing capabilities reconfiguration in manufacturing strategy for sustainable competitive advantage. International Journal of Operational Research, 10(1), 82–101.

Lee, G., & **a, W. (2010). Toward agile: An integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative field data on software development agility. MIS Quarterly, 34(1), 87–114.

Liang, H., Saraf, N., Hu, Q., & Xue, Y. (2007). Assimilation of enterprise systems: the effect of institutional pressures and the mediating role of top management. MIS Quarterly, 59–87.

Lieberman, M. B., & Montgomery, D. B. (1988). First-mover advantages. Strategic Management Journal, 9(S1), 41–58.

Liu, A., Shen, L., Tan, Y., Zeng, Z., Liu, Y., & Li, C. (2018). Food integrity in China: Insights from the national food spot check data in 2016. Food Control, 84, 403–407.

Liu, H., Wei, S., Ke, W., Wei, K. K., & Hua, Z. (2016). The configuration between supply chain integration and information technology competency: A resource orchestration perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 44, 13–29.

Liu, Y., Zhu, Q., & Seuring, S. (2020). New technologies in operations and supply chains: Implications for sustainability. International Journal of Production Economics, 229(107889), 1–5.

Lwesya, F., Mwakalobo, A. B. S., & Mbukwa, J. (2021). Utilization of non-financial business support services to aid development of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Tanzania. Small Business International Review, 5(2), 1–15.

Maheshwari, P., Kamble, S., Pundir, A., Belhadi, A., Ndubisi, N. O., & Tiwari, S. (2021). Internet of things for perishable inventory management systems: an application and managerial insights for micro, small and medium enterprises. Annals of Operations Research, 1–29.

Malhotra Naresh, Hall John, Shaw Mike, Peter Oppenheim. Marketing research: an applied orientation. 2nd edn. Sydney7 Prentice Hall; 2002.

Mani, V., Delgado, C., Hazen, B. T., & Patel, P. (2017). Mitigating supply chain risk via sustainability using big data analytics: Evidence from the manufacturing supply chain. Sustainability, 9(4), 1–21.

Mikalef, P., & Krogstie, J. (2020). Examining the interplay between big data analytics and contextual factors in driving process innovation capabilities. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(3), 260–287.

Mikalef, P., & Pateli, A. (2017). Information technology-enabled dynamic capabilities and their indirect effect on competitive performance: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Journal of Business Research, 70, 1–16.

Modgil, S., Gupta, S., Stekelorum, R., & Laguir, I. (2021). AI technologies and their impact on supply chain resilience during COVID-19. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management., 52(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-12-2020-0434

Mu, J., & Di Benedetto, C. A. (2011). Strategic orientations and new product commercialization: Mediator, moderator, and interplay. R&D Management, 41(4), 337–359.

Neely, A., Gregory, M., & Platts, K. (1995). Performance measurement system design: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Operations and Production Management., 15(4), 80–116.

Ngo, L. V., Bucic, T., Sinha, A., & Lu, V. N. (2019). Effective sense-and-respond strategies: Mediating roles of exploratory and exploitative innovation. Journal of Business Research, 94, 154–161.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill.

Nystrom, P. C., Ramamurthy, K., & Wilson, A. L. (2002). Organizational context, climate and innovativeness: Adoption of imaging technology. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 19(3–4), 221–247.

Park, Y., & Mithas, S. (2020). Organized complexity of digital business strategy: A configurational perspective. MIS Quarterly, 44(1), 85–127.

Pavlou, P. A., & El Sawy, O. A. (2011). Understanding the elusive black box of dynamic capabilities. Decision Sciences, 42(1), 239–273.

Peng, D. X., Schroeder, R. G., & Shah, R. (2008). Linking routines to operations capabilities: A new perspective. Journal of Operations Management, 26(6), 730–748.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Priem, R. L., & Butler, J. E. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 22–40.

Psillaki, M., Tsolas, I. E., & Margaritis, D. (2010). Evaluation of credit risk based on firm performance. European Journal of Operational Research, 201(3), 873–881.

Rai, A., Patnayakuni, R., & Seth, N. (2006). Firm performance impacts of digitally enabled supply chain integration capabilities. MIS Quarterly, 225–246.

Rialti, R., Zollo, L., Ferraris, A., & Alon, I. (2019). Big data analytics capabilities and performance: Evidence from a moderated multi-mediation model. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 149(119781), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119781

Ritter, T., & Pedersen, C. L. (2020). Digitization capability and the digitalization of business models in business-to-business firms: Past, present, and future. Industrial Marketing Management, 86, 180–190.

Santoro, G., Vrontis, D., & Pastore, A. (2017). External knowledge sourcing and new product development: Evidence from the Italian food and beverage industry. British Food Journal., 119(11), 2373–2387.

Sariyer, G., Mangla, S. K., Kazancoglu, Y., Ocal Tasar, C., & Luthra, S. (2021). Data analytics for quality management in Industry 4.0 from a MSME perspective. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04215-9

Serazetdinova, L., Garratt, J., Baylis, A., Stergiadis, S., Collison, M., & Davis, S. (2019). How should we turn data into decisions in AgriFood? Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 99(7), 3213–3219.

Shafiq, A., Ahmed, M. U., & Mahmoodi, F. (2020). Impact of supply chain analytics and customer pressure for ethical conduct on socially responsible practices and performance: An exploratory study. International Journal of Production Economics, 225(107571), 1–12.

Sharon, M., Abirami, C. V., & Alagusundaram, K. (2014). Grain storage management in India. Journal of Postharvest Technology, 2(1), 12–24.

Shin, H., Lee, J. N., Kim, D., & Rhim, H. (2015). Strategic agility of Korean small and medium enterprises and its influence on operational and firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 168, 181–196.

Swink, M., Narasimhan, R., & Kim, S. W. (2005). Manufacturing practices and strategy integration: Effects on cost efficiency, flexibility, and market-based performance. Decision Sciences, 36(3), 427–457.

Srinivasan, R., & Swink, M. (2018). An investigation of visibility and flexibility as complements to supply chain analytics: An organizational information processing theory perspective. Production and Operations Management, 27(10), 1849–1867.

Tam, W., & Yang, D. (2005). Food safety and the development of regulatory institutions in China. Asian Perspective, 29(4), 5–36.

Tang, Y. K., & Konde, V. (2020). Differences in ICT use by entrepreneurial micro-firms: Evidence from Zambia. Information Technology for Development, 26(2), 268–291.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

United Nations report. Accessed through https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/MSMEs_and_SDGs.pdf

Vanpoucke, E., Vereecke, A., & Wetzels, M. (2014). Develo** supplier integration capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Operations Management, 32(7–8), 446–461.

Von Alan, R. H., March, S. T., Park, J., & Ram, S. (2004). Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 28(1), 75–105.

Wang, Z., Wang, N., Su, X., & Ge, S. (2020). An empirical study on business analytics affordances enhancing the management of cloud computing data security. International Journal of Information Management, 50, 387–394.

Wedel, M., & Kannan, P. K. (2016). Marketing analytics for data-rich environments. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 97–121.

Weerawardena, J., Mort, G. S., Salunke, S., Knight, G., & Liesch, P. W. (2015). The role of the market sub-system and the socio-technical sub-system in innovation and firm performance: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 221–239.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180.

Winter, S. G. (2000). The satisficing principle in capability learning. Strategic Management Journal, 981–996.

Wong, C. W., Lai, K. H., & Cheng, T. C. E. (2011). Value of information integration to supply chain management: Roles of internal and external contingencies. Journal of Management Information Systems, 28(3), 161–200.

Wu, L., Hitt, L., & Lou, B. (2020). Data analytics, innovation, and firm productivity. Management Science, 66(5), 2017–2039.

Yan, Y. (2012). Food safety and social risk in contemporary China. The Journal of Asian Studies, 71(3), 705–729.

Zhan, Y., Tan, K. H., Li, Y., & Tse, Y. K. (2018). Unlocking the power of big data in new product development. Annals of Operations Research, 270(1), 577–595.

Zhang, C., Wang, X., Cui, A. P., & Han, S. (2020). Linking big data analytical intelligence to customer relationship management performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 91, 483–494.

Zheng, L. J., Zhang, J. Z., Wang, H., & Hong, J. F. (2022). Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on the dual nature of innovative activities in MSMEs: A data-agility-innovation perspective. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-022-04800-6

Zhu, S., Dong, T., & Luo, X. R. (2021). A longitudinal study of the actual value of big data and analytics: The role of industry environment. International Journal of Information Management, 60(102389), 1–15.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the constructive comments of the referees on an earlier version of this paper. The first author was supported in part by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University under grant number P0035708. The second author was supported in part by The Hong Kong Polytechnic University under grant number CD4T.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represents a conflict of interest in connection with the work submitted.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Coded articles: summary of the main studies on the impact of organizational capability on business performance

Study | Code | Type of paper | Sample source/sample size (N) | Level of analysis | Dependent variables (DVs) | Independent variables (IVs) | Theory applied | Findings/contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Akter et al. (2016) | A1 | Empirical research | (1) 2 Delphi studies; (2) Surveys: 152 U.S. business analysts | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variables: big data analytics (BDA) management capability, BDA talent capability, BDA technology capability; Mediating variable: BDA capability | Resource-based theory | (1) Value of entanglement conceptualization of a higher-order BDA capability model and its impact on firm performance; (2) moderating effects of analytics capability–business strategy alignment on the relationship between BDAC and business performance |

Ashrafi et al. (2019) | A2 | Empirical research | Survey: 154 companies with 2 respondents each (CIO/CEO) | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variable: business analytics (BA) capabilities; Mediating variables: information quality, firm agility, innovative capability; Moderating variables: market turbulence, technological turbulence | Resource-based view | (1) BA capabilities strongly influence a firm’s agility through increased innovative capability and information quality; (2) technological and market turbulence moderates the effect of firm agility on firm performance |

Chen and Lin (2021) | A3 | Empirical research | Survey: 231 middle or senior manager/IT professionals/chief executives/CEOs involved in using business intelligence technology in business operations | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variable: sensing capability; Mediating variables: transforming capability, driving capability | Dynamic capability theory, organizational evolutionary theory | Strong, positive and cumulative relationships among business intelligence-related dynamic capabilities and structural components of the Sense–Transform–Drive conceptual model can increase firm performance and operating efficiency |

Chi et al. (2010) | A4 | Empirical research | Secondary data: 12 major automakers (U.S. market) 1988–2003 | Organizational | Competitive action: including (1) action heterogeneity, (2) action complexity, (3) action volume | Independent variable: network density, structural holes; Mediating variables: IT-enabled capability: (a) sensing, (b) responding | Social network theory | IT-enabled capability plays (1) a strengthening role in the relationship between competitive action and network structure for companies embedded in dense network structures and (2) a substitutive role when companies lack advantageous access to brokerage opportunities |

Fosso Wamba et al. (2020) | A5 | Empirical research | Survey: 202 mid-level executive analytics professionals | Organizational | Organizational outcomes including (1) customer linking capability, (2) financial performance, (3) market performance, (4) strategic business value | Independent variable: big data analytics (BDA)-enabled dynamic capability, including BDA-enabled sensing capability; Mediating variable: business analytics culture, including analytics culture | Dynamic capabilities view; resource-based view | (1) Analytics culture and BDA-enabled sensing capability positively influence organizational outcomes; (2) an analytics culture mediates the effect of BDA-enabled sensing capability on organizational outcomes |

Fosso Wamba et al. (2020) | A6 | Empirical research | Survey: 281 supply chain practitioners in the U.S | Organizational | Business performance, including (1) costing performance, (2) operational performance | Independent variables: big data analytics, environmental dynamism; Mediating variables: supply chain ambidexterity, including (1) supply chain agility (2) supply chain adaptability | Dynamic capability view | Big data analytics enhances organizational performance, supply chain adaptability, and supply chain agility, contingent upon the level of environmental dynamism |

Gu et al. (2021) | A7 | Empirical research | Survey: 108 managers (or above), buyers, purchasing agents in manufacturing and service industries | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variable: supplier development; Mediating variable: big data analytics (BDA) capability | Contingency theory, dynamic capability view, resource-based view | A firm’s BDA capability has a (1) direct positive impact on firm performance/supplier development and (2) strong mediating/moderating effect on supplier development, affecting business performance improvement |

Hallikas et al. (2021) | A8 | Empirical research | Survey: 101 managers and experts in manufacturing and service industries | Organizational | Business performance | Independent variables: external data analytics capability, internal data analytics capability; Mediating variables: digital procurement capability, supply chain performance | Dynamic capability view, resource-based view | (1) There are significant positive relationships between supply chain performance, digital procurement capabilities, and data analytics capabilities; (2) digital procurement capabilities mediate the positive relationship between external data analytics capability and supply chain performance |

Helfat and Peteraf (2015) | A9 | Conceptual paper | N/A | Organizational | N/A | N/A | N/A | The dynamic managerial capabilities of reconfiguring, seizing, and sensing contribute to differential firm performance under changing conditions |

Krishnamoorthi and Mathew (2018) | A10 | Empirical research | Case study: 9 interviews (2014, 2015) with analytics team leaders/senior executives in 2 diverse organizations deploying analytics | Organizational | Business performance | Independent variables: analytics resources, including (1) business analytics capability, (2) analytics technology assets; Moderating variables: analytics value enhancers, organizational-level variables | Resource-based view | Analytics resources comprising business analytics capabilities and analytics technology assets contribute to firm performance |

Kristoffersen et al. (2021) | A11 | Empirical research | Survey: 125 top-level managers of firms across Europe | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variable: business analytics capability; Mediating variables: resource orchestration capability, circular economy implementation | Theory of resource orchestration | (1) The influence of business analytics capability on firm performance is fully, but not directly, mediated by circular economy implementation and resource orchestration capability; (2) firms with a strong business analytics capability: (a) have a greater ability to excel in a circular economy, (b) increase their resource orchestration capability, (c) build a more sustainable competitive advantage, and (d) have improved firm performance |

Meriton et al. (2020) | A12 | Review paper | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Dynamic capability view, resource-based view | (1) The generative mechanisms of value in big data technology-enabled supply chains operate at the level of supply chain processes; (2) agility and resilience emerge from big data technology-enabled supply chain management research |

Naseer et al. (2021) | A13 | Empirical research | Multiple case study: 20 expert interviews with cybersecurity analytics professionals | Organizational | Enterprise cybersecurity performance, including (1) efficiency, (2) effectiveness | Independent variables: real-time analytics (RTA) capability, including (1) complex event processing, (2) automated decision-making, (3) on-demand and continuous data analysis; Mediating variables: incident response (IR) agility, including (1) flexibility in IR, (2) swiftness in IR, (3) innovation in IR; Moderating variables: cyber threat environment, including (1) complexity, (2) dynamism | Contingent resource-based view | Firms enable agile characteristics (innovation, flexibility, and swiftness) in IR processes using the characteristics of RTA capability (on-demand and continuous data analysis, decision automation, and complex event processing) to respond to and detect cybersecurity incidents as they occur to improve cybersecurity performance |

Ngo et al. (2019) | A14 | Empirical research | Survey: 150 Vietnamese firms | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variables: technology-sensing capability, market-sensing capability, exploration–exploitation interaction; Mediating variables: explorative innovation, exploitative innovation | Dynamic capabilities view | Exploitative and exploratory innovations are salient modi operandi through which the effects of market-sensing and technology-sensing capabilities influence business performance |

Park and Mithas (2020) | A15 | Empirical research | Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis of 376 organizational level cases in multiple economic sectors during 1999–2006 | Organizational | Financial performance, customer performance | Independent variables: IT-enabled analytics capability, leadership capability, strategic planning capability, customer focus capability, HR focus capability, process management capability | Complexity theory | IT-enabled information analytics capabilities are critical components of the configurations in which they play multi-faceted roles, varying from enabling to counter-productive to no role in a given context |

Shafiq et al. (2020) | A16 | Empirical research | Survey: 254 U.S. manufacturers | Organizational | Financial performance | Independent variable: Customer pressure for ethical conduct, including (1) code of conduct enforcement; Mediating variables: Exsupero-regulatory social practices, including (1) supply chain transparency, (2) employee-focused social practices; Moderating variables: supply chain analytics capability | Resource-based view, stakeholder theory | Supply chain analytics capabilities interact synergistically with customer pressure for ethical conduct to improve suppliers’ financial and social performance |

Shin et al. (2015) | A17 | Empirical research | Survey: 244 South Korean SMEs | Organizational | Technology capability, collaborative innovation, organizational learning, internal alignment, firm performance | Independent variable: strategic agility; Mediating variable: operational responsiveness | N/A | The strategic intent of South Korean SMEs to improve agility positively influences customer retention and operational performance |

Srinivasan and Swink (2017) | A18 | Empirical research | Survey: 191 responses from firms in 30 countries (56.8% in the U.S.; 67.5% manufacturing-related and the remainder service-related). The 20 industries included automotive and transportation (8.38%), consumer goods (7.33%), and chemicals (4.19%) | Organizational | Operational performance | Independent variable: demand visibility, supply visibility; Mediating variable: analytics capability; Moderating variables: organizational flexibility | Organizational information processing theory | (1) Supply and demand visibility are associated with the development of analytics capability; (2) analytics capability is associated with operational performance when organizations possess the flexibility to act on analytics-generated insights efficiently and quickly; (3) analytics capability and organizational flexibility are valuable complementary capabilities for firms in volatile markets |

Tallon and Pinsonneault (2011) | A19 | Empirical research | Survey: IT and business executives in 241 firms | Organizational | Firm performance | Independent variable: strategic IT alignment; Mediating variable: firm agility; Moderating variables: environmental volatility, IT flexibility | Resource-based view | (1) There are positive/significant links between alignment (can be thought of as sensing capability) and agility and between firm performance and agility; (2) agility fully mediates the effect of alignment on performance; (3) IT infrastructure flexibility moderates the link between agility and alignment in a volatile environment; (4) the influence of IT infrastructure flexibility on agility is as strong as that of alignment on agility; (5) agility and alignment are concurrent and critical organizational goals |

Upadhyay and Kumar (2020) | A20 | Empirical research | Survey: 800 IT consultants for firms working in big data analytics (India) | Organizational | Firm performance (FP) | Independent variable: internal analytics knowledge (KN); Mediating variables: big data analytics capability (BDAC), organizational culture (CL) | Dynamic capability view; resource-based view; sociomaterialism theory | (1) CL plays a complementary mediatory role between KN and BDAC that influences FP; (2) BDAC plays a mediatory role between CL and FP |

Vanpoucke et al. (2014) | A21 | Empirical research | Survey: 719 firms in 20 countries in America, Europe, and Asia | Organizational | Financial performance, integration sensing, integration seizing, integration transforming | Independent variable: supplier integrative capability (SIC); Mediating variables: market performance, operational performance (process flexibility, cost efficiency) | Dynamic capabilities view; resource-based view; theory of complementarity | (1) Transforming, seizing, and integrating sensing capabilities are complementary, exist simultaneously, enhance cost efficiency/process flexibility and help firms avoid the traditional flexibility/cost tradeoff; (2) market and technological dynamics strengthen the SIC effect on operational performance, but supply base complexity attenuates this link |

Zhu et al. (2021) | A22 | Empirical research | Modelling: secondary data on big data and analytics implementation 2010–2020 | Organizational | Firm performance, including (1) operational efficiency, (2) business growth | Independent variables: BDA implementation Moderating variables: industry environment, including (1) complexity, (2) dynamism, (3) munificence | Organizational learning theory | (1) BDA implementation significantly affects operational efficiency and business growth; (2) the impact of BDA on operational efficiency is amplified in less complex and dynamic environments; (3) the BDA-business growth relationship is amplified in munificent, complex, and dynamic environments |

This study | N/A | Empirical research | Survey: 149 employees of MSMEs in the food industry | Organizational | Operational performance | Independent variables: (1) analytics capability, (2) sensing capability Moderating variables: data-driven culture | Resource-based view; dynamic capability view; strategic fit theory | (1) Sensing and analytics capabilities positively affect operational performance; (2) a data-driven culture positively moderates the influence of organizational capability on operational performance |

Appendix B: Papers collected in literature review and major studies

A1. Akter, S., Wamba, S. F., Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R., & Childe, S. J. (2016). How to improve firm performance using big data analytics capability and business strategy alignment?. International Journal of Production Economics, 182, 113–131.

A2. Ashrafi, A., Ravasan, A. Z., Trkman, P., & Afshari, S. (2019). The role of business analytics capabilities in bolstering firms’ agility and performance. International Journal of Information Management, 47, 1–15.

A3. Chen, Y., & Lin, Z. (2021). Business intelligence capabilities and firm performance: A study in China. International Journal of Information Management, 57, 102232, 1–15.

A4. Chi, L., Ravichandran, T., & Andrevski, G. (2010). Information technology, network structure, and competitive action. Information Systems Research, 21(3), 543–570.

A5. Wamba, S. F., Queiroz, M. M., Wu, L., & Sivarajah, U. (2020). Big data analytics-enabled sensing capability and organizational outcomes: assessing the mediating effects of business analytics culture. Annals of Operations Research, 1–20.

A6. Wamba, S. F., Dubey, R., Gunasekaran, A., & Akter, S. (2020). The performance effects of big data analytics and supply chain ambidexterity: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. International Journal of Production Economics, 222, 107498. 1–14.

A7. Gu, V. C., Zhou, B., Cao, Q., & Adams, J. (2021). Exploring the relationship between supplier development, big data analytics capability, and firm performance. Annals of Operations Research, 1-22.

A8.Hallikas, J., Immonen, M., & Brax, S. (2021). Digitalizing procurement: the impact of data analytics on supply chain performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 26(5), 629–646.

A9. C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2015). Managerial cognitive capabilities and the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 36(6), 831-850.

A10. Krishnamoorthi, S., & Mathew, S. K. (2018). Business analytics and business value: A comparative case study. Information & Management, 55(5), 643–666.

A11. Kristoffersen, E., Mikalef, P., Blomsma, F., & Li, J. (2021). The Effects of Business Analytics Capability on Circular Economy Implementation, Resource Orchestration, Capability and Firm Performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 108205, 1–19.

A12. Meriton, R., Bhandal, R., Graham, G., & Brown, A. (2020). An examination of the generative mechanisms of value in big data-enabled supply chain management research. International Journal of Production Research, 1–28.

A13. Naseer, A., Naseer, H., Ahmad, A., Maynard, S. B., & Siddiqui, A. M. (2021). Real-time analytics, incident response process agility and enterprise cybersecurity performance: A contingent resource-based analysis. International Journal of Information Management, 59, 102334.1–10.

A14. Ngo, L. V., Bucic, T., Sinha, A., & Lu, V. N. (2019). Effective sense-and-respond strategies: Mediating roles of exploratory and exploitative innovation. Journal of Business Research, 94, 154–161.

A15. Park, Y., & Mithas, S. (2020). Organized Complexity of Digital Business Strategy: A Configurational Perspective. MIS Quarterly, 44(1), 85–127.

A16. Shafiq, A., Ahmed, M. U., & Mahmoodi, F. (2020). Impact of supply chain analytics and customer pressure for ethical conduct on socially responsible practices and performance: An exploratory study. International Journal of Production Economics, 225, 107571, 1–12.

A17. Shin, H., Lee, J. N., Kim, D., & Rhim, H. (2015). Strategic agility of Korean small and medium enterprises and its influence on operational and firm performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 168, 181–196.

A18. Srinivasan, R., & Swink, M. (2018). An investigation of visibility and flexibility as complements to supply chain analytics: An organizational information processing theory perspective. Production and Operations Management, 27(10), 1849–1867.

A19. Tallon, P. P., & Pinsonneault, A. (2011). Competing perspectives on the link between strategic information technology alignment and organizational agility: insights from a mediation model. MIS Quarterly, 463–486.

A20. Upadhyay, P., & Kumar, A. (2020). The intermediating role of organizational culture and internal analytical knowledge between the capability of big data analytics and a firm’s performance. International Journal of Information Management, 52, 102100. 1–16.

A21. Vanpoucke, E., Vereecke, A., & Wetzels, M. (2014). Develo** supplier integration capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Operations Management, 32(7–8), 446–461.

A22. Zhu, S., Dong, T., & Luo, X. R. (2021). A longitudinal study of the actual value of big data and analytics: The role of industry environment. International Journal of Information Management, 60, 102389, 1–15.

Appendix C: Profile of the respondents (n = 149)

Demographic | Category | n = 149 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

Gender | Men | 86 | 58 |

Women | 63 | 42 | |

Age group (years) | 21–25 | 20 | 13 |

26–30 | 56 | 38 | |

31–35 | 45 | 30 | |

36–40 | 22 | 15 | |

41–45 | 4 | 3 | |

45–50 | 2 | 1 | |

Education level | Secondary | 6 | 4 |

Diploma | 20 | 13 | |

Associate degree | 4 | 3 | |

Bachelor’s degree | 102 | 68 | |

Master’s degree | 12 | 8 | |

Doctorate or above | 4 | 3 | |

Occupation | CEO | 2 | 1 |

CFO | 1 | 1 | |

Supply chain manager | 24 | 16 | |

R&D manager | 7 | 5 | |

Product development manager | 16 | 11 | |

Merchandising manager | 10 | 7 | |

Production manager | 15 | 10 | |

Logistics (or ship**) manager | 21 | 14 | |

Sales/marketing manager | 12 | 8 | |

Food safety manager | 13 | 8 | |

Quality assurance manager | 10 | 7 | |

Owner | 18 | 12 | |

Engaged in food industry (Years) | 5–10 | 111 | 74 |

11–20 | 37 | 25 | |

21 or above | 1 | 1 | |

Engaged in current position (Years) | 5–10 | 127 | 85 |

11–20 | 21 | 14 | |

21 or above | 1 | 1 | |

Number of employees in current company | 1–9 | 29 | 19 |

10–49 | 43 | 29 | |

50–249 | 77 | 52 | |

Age of company (Years) | 5–10 | 45 | 30 |

11–20 | 79 | 53 | |

21 or above | 25 | 17 | |

Type of company | Food producer | 36 | 24 |

Food processor | 30 | 20 | |

Wholesaler | 25 | 17 | |

Retailer | 30 | 20 | |

Restaurant | 28 | 19 |

Appendix D: Scale items

A seven-point Likert scale was used for all the items (1 = “strongly disagree”; 4 = “neutral”; 7 = “strongly agree”).

4.1 Analytics capability (Srinivasan & Swink, 2018)

Please tell us the degree to which data management and analysis techniques are used to improve supply chain strategies and activities:

AC1: We use advanced analytical techniques (e.g., simulation, optimization, regression) to improve decision making.

AC2: We easily combine and integrate information from many data sources for use in our decision making.

AC3: We routinely use data visualization techniques (e.g., dashboards) to assist users or decision-maker in understanding complex information.

AC4: Our dashboards give us the ability to decompose information to help root cause analysis and continuous improvement.

AC5: We deploy dashboard applications/information to our managers’ communication devices (e.g., smart phones, computers).

4.2 Sensing capability (Pavlou & El Sawy, 2011)

SC1: We frequently scan the environment to identify new business opportunities.

SC2: We periodically review the likely effect of changes in our business environment on customers.

SC3: We often review our product development efforts to ensure they are in line with what the customers want.

SC4: We devote a lot of time implementing ideas for new products and improving our existing products.

4.3 Data-driven culture (Zhang et al., 2020)

DDC1: We consider data a tangible asset.

DDC2: We base our decisions on data rather than on instinct.

DDC3: We are willing to override our own intuition when data contradict our viewpoints.

DDC4: We continuously coach our employees to make decisions based on data.

4.4 Operational performance (Wang et al., 2012)

Over the past three years, we have performed better than our key competitors:

OP1. Decreasing product/service delivery cycle time.

OP2. Rapidly responding to market demand changes.

OP3. Rapidly bringing new products/services to the market.

OP4. Rapidly entering new markets.

OP5. Rapidly confirming customer orders.

OP6. Rapidly handling customer complaints.

OP7. Establishing a strong and continuous bond with customers.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, D.T.W., Ngai, E.W.T. The effects of analytics capability and sensing capability on operations performance: the moderating role of data-driven culture. Ann Oper Res (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-023-05241-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-023-05241-5