Abstract

The reform process of the CAP is increasingly open to actors that apply different frames. Recent research reveals the consistent use of five frames during CAP reform processes: the policy mechanism frame, the farmers’ economic frame, the societal concerns frame, the budgetary frame, and the foreign trade frame. Our qualitative content analysis of 1,155 newspaper articles from Austria’s largest agricultural newspaper published between 01/10/2010 and 31/01/2015 confirms that these five frames are also used in national CAP reporting and consist of subframes. The European Commission (EC), the European Parliament, and the Council of the European Union, which are involved in the CAP legislative process, mainly use the policy mechanism frame. The farmers’ economic frame and the policy mechanism frame are applied throughout the reform process. The societal concerns frame is gradually used over time, while the foreign trade frame is limited to specific events. The budgetary frame increasingly refers to public money for public goods, which indicates that the EC and other actors put efforts into legitimising the CAP. The results emphasise that both, agricultural and environmental actors use agricultural media to generate support for or condemnation of agricultural policy and thereby affect political agenda-setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several actors influence the political agenda-setting (Burkart 2019). They can be differentiated into actors who lobby and advocate, and actors who have decision-making power (Dermont et al. 2017). Media can take up the topics, suggestions and concerns raised by the actors, and thereby contribute to the understanding and approval of a policy by its stakeholders and recipients – a pre-condition for being successful in agenda-setting and policy formulation (Ingold 2011; Kriesi and Jegen 2001; Simantov 1973), and for inducing policy change (Dermont et al. 2017).

Closely interlinked with agenda-setting is framing, also referred to as second level agenda-setting (Matthes 2007). Every public discourse is a competition between actors for the dominant frame that finally lays the foundation for policy action (Entman 1993; Matthes 2007). Frames can be identified among different actors including strategic communicators, journalists, and recipients. Journalists can adopt the frames of strategic communicators and contribute their own views. Through selection and salience, they construct a specific picture of events (Hallahan 1999; Matthes 2007).

Framing research originates from social sciences, psychology and communication science (Matthes 2007). The sociologist Goffman is considered a pioneer in framing research and defines a frame as a structure of meaning that enables an actor to assess and react to a situation (Goffman 1980). The psychologists Tversky and Kahneman (1981) demonstrate that decisions depend on whether a problem is framed in the winning or losing perspective. In communication science, Entman (1993) has significantly influenced framing research. He argues that “to frame is to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communication context, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described” (Entman 1993, p. 52). Accordingly, frames consist of frame elements that define a certain problem, describe the causes of the problem, evaluate the problem and point out possible solutions (Entman 1993; Matthes 2007). Frames are reflected by key concepts and keywords in the text of interest (Entman 1991).

Framing has been applied for a wide range of societal and policy phenomena, however, previous research on agricultural policy mainly focused on agenda-setting, decision making processes, implementation, and evaluation, rather than empirical frame analysis (Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Erjavec and Erjavec 2015; Liepins and Bradshaw 1999; Potter 2006). Available frame analyses in the field of agriculture can be distinguished along four dimensions: (i) research topics, (ii) media type, (iii) reform period, and (iv) actor groups (Table 1). The research topics addressed are identifying resilience frames (Buitenhuis et al. 2022), identifying food security frames (Candel et al. 2014), identifying the European Commission’s frames of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021), analysing actions of two main policy actors to address nutrient leaching (Isaac and de Loë 2022), analysing the presentation of the CAP in Austria’s media (Kasparek-Koschatko et al. 2020), or framing scale increase in Dutch agricultural policy (van Lieshout et al. 2013), while framing of the CAP reforms have received little academic attention so far. The European Commission (EC), one of the main actors in the CAP reform process, regularly modifies its frames to justify the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021) for which a large (though declining) share of the European Union’s budget is allocated (Nègre 2022). However, frame analyses have not yet been conducted in order to examine whether the EC’s frames are also used in national media or by national actors, and whether national actors introduce their own frames. Moreover, the changes in applied frames have not yet been analysed for the period of a whole reform process for national media. Our study makes three major contributions to literature. First, our study adds value to the empirical frame analysis using a large data set. Second, the results of our study could be useful for the actors involved in the CAP reform process such that they inform their communication strategies towards agenda-setting as well as creating support for policy design, implementation, and outcome. Third, a structured analyses of frames and actors using these frames may provide insights into successful media communication and transparency for the interested observers of the CAP reform processes.

We aim to fill the revealed gaps by employing frame analysis for the CAP reform 2013 in national media. In particular, we aim to examine whether the frames identified in the EC strategic papers (according to Erjavec and Erjavec (2021)) are reflected in national media reporting about the CAP reform 2013, whether these frames consist of subframes and whether the identified frames change in course of the reform process. We use newspaper articles published in Austria’s largest agricultural newspaper the “Bauernzeitung” in the period from 01/10/2010 to 31/01/2015. In our analysis, we include all actors active in the CAP reform process. Hence, we address the following research questions:

-

To what extent are the frames employed by the EC in the CAP strategic papers since 1991 (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021) used in media reports about the CAP reform 2013 in Austria’s largest agricultural newspaper, and what additional frames and subframes are used?

-

What changes in frames can be observed in the CAP reform process 2013 in Austria’s largest agricultural newspaper?

The CAP reform process

The CAP states four general objectives: increase agricultural productivity, ensure a fair standard of living for farmers, stabilise markets for agricultural products, and ensure the availability of agricultural products at reasonable prices (European Council 2022). These objectives are prioritized along societal expectations and decided on in each CAP reform. The CAP reforms follow a pre-defined, structured process. They start with the European Commission’s (EC) presentation of the strategic paper, which sets out the content and objectives of the upcoming reform (Cunha and Swinbank 2011). About one year later, the EC presents the legislative proposals for the new CAP. The European Parliament (EP) acts as a full co-legislator in agriculture since the CAP reform 2013 (European Parliament 2022). The legislative proposals are then negotiated between the EC, the Council of the European Union and the EP (European Parliament 2020). Agricultural policy negotiations are closely linked to the timeline of the multi-annual financial framework, which co-determines the scope and design of the CAP (Nègre 2022).

Major points of discussion during the CAP reform 2013 were the decreasing budget share for agriculture, the alignment of direct payments within and between member states, the abolition of the milk quota in 2015 and new regulations that respond to environmental concerns (Hofreither and Sinabell 2014; Reeh 2015). Cross-compliance was simplified, and green direct payments (further referred to as greening) were introduced in Pillar I in 2015. Greening requirements include practices that are beneficial for the environment and the climate and are compulsory for farmers to receive direct payments (European Commission 2013a). For Pillar II, rural development, key objectives were specified which include enhancing farmers’ competitiveness, innovation and risk management, preserving ecosystems and promoting resource use efficiency (European Commission 2013b).

Several authors use discourse analysis to examine the CAP reform processes (Cloke 1996; Daugbjerg and Swinbank 2007; Erjavec and Erjavec 2015, 2009; Liepins and Bradshaw 1999; Potter 2006; Potter and Tilzey 2005). They identify three dominating discourses, i.e., productivity-oriented discourse, multi-functional discourse, and neoliberal discourse, and they reveal a rise in multi-functional and neo-liberal discourses since the CAP’s beginnings. In the early CAP era, the productivity-oriented discourse dominated and postulated protectionism i.e. the state has to support the agricultural sector for sufficient food supply (Potter 2006; Potter and Tilzey 2005). Erjavec and Erjavec (2015) describe the productivity-oriented discourse to be characterized by keywords such as “food production” or “sufficient food supply”. Throughout the last years, the use of the productivity-oriented discourse constantly declined to legitimise the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec 2014). While EU and national policy makers stopped using these keywords, farmers’ interest groups at EU and national level kept using these productivity-oriented keywords to justify the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015). The multi-functional discourse is characterized by keywords such as “provision of public goods”, “protection of biodiversity” and “sustainable use of natural resources” and has recently been partially replaced by the neoliberal discourse and its associated keywords of “quality products” and “competitiveness” (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015). While research emphasises the need for synergies between agriculture and environmental protection, the productivity-oriented discourse is strengthened by farmers’ interest groups (Erjavec and Erjavec 2015). This illustrates that interest in the CAP is high with various actors being involved in the reform process.

Materials and methods

Method

In our analysis, we follow the frame definition by Entman (1993) to identify the content-bearing and thus frame-relevant elements. We create frames by identifying a logical chain of framing devices (i.e. key concepts that describe the topic or main idea and keywords) and frame elements (Entman 1993; Gamson and Modigliani 1989; Van Gorp 2010). Matthes (2007) distinguishes between an explicit frame that mentions all four frame elements (i.e. define a certain problem, describe the cause of the problem, evaluate the problem, and point out possible solutions) within one newspaper article, and an implicit frame that mentions not all, but at least two frame elements.

To define the problem, we consider the actor and the topic that is being talked about, as suggested by Matthes (2007). The cause of the problem can be attributed to a person or a situation, and solution attributions are also considered in the analysis. Competence can be attributed or denied to persons, and measures can be demanded or required to be refrained from (Matthes 2007). A moral evaluation can refer to the moral or evaluative classification of a problem by the actor using the frame. While some issues have already an inherent evaluation (Matthes 2007), others are depending on the actor and can thus be evaluated differently. The evaluation is articulated as being either positive or negative.

Data

We identify and select newspaper articles by using the APA Online Manager tool, an electronic press archive. The German search substring “'GAP' oder ‘Agrarpol*’” (‘CAP’ or ‘agricultural pol*’) is used to find relevant newspaper articles. We use the exact search for the German keyword “GAP” to exclude the English word “gap”. Using the substring “‘Agrarpol*’” with an asterisk ensures that information on, for instance,”agricultural politicians” and the”Common Agricultural Policy” (“Agrarpolitiker”, “Agararpolitikerin”, “Gemeinsame Agrarpolitik”) are included in the search results. The newspaper articles cover the entire period of the CAP reform 2013, which we define as per 01/10/2010 until 31/01/2015. The strategic paper of the EC defines the start of a CAP reform. It was published by the EC on 18/11/2010 for the reform 2013. The CAP implementation defines the end of the reform process (i.e. 01/01/2015). We add roughly one month before and after the official start and end to reflect media coverage of these critical events. A further extension of the period is not necessary because media coverage decreased after January 2015. Initially, we have included all Austrian quality newspapers, weekly magazines, and agricultural newspapers in the search, which constitutes 31 different sources. Altogether, 4,890 newspaper articles have been retained from the electronic press archive, whereby 3,409 newspaper articles remain after deleting duplicates, advertisements and newspaper articles not directly related to the CAP. We select the agricultural newspaper Bauernzeitung for further analysis because it has the highest absolute number of published newspaper articles on the CAP reform, and it is the only media type that covers the entire CAP reform process. Moreover, the Bauernzeitung has the highest media reach in the agricultural sector, with farmers and agricultural policy makers being the target groups. Mainstream media such as daily newspapers present the discourse from other media as well, however, mainstream media pass on the discourses in a simplified and often very selective way (Ferree et al. 2002). In the period of investigation, the Bauernzeitung had a weekly circulation of approximately 120,000. We include all types of newspaper articles (i.e. reports, opinion pieces, newsflashes). In total, 1,155 newspaper articles are retained from the Bauernzeitung for the qualitative content analysis. The number of published newspaper articles is relatively constant over the first half of each year and increases by the end of each year, reaching its peak at the end of the reform process. Pictures and placement within the newspaper are not recorded because this information is not available in the electronic press archive. Hence, our analysis focuses on the media texts.

Data analysis

We use qualitative content analysis (Mayring 2002) to identify the frames and subframes referring to the CAP reform 2013 in the articles published in Austria’s largest agricultural newspaper Bauernzeitung. Qualitative content analysis is a method to describe the content and formal characteristics of a text systematically and intersubjectively comprehensible (Früh 2001). We combine deductive and inductive coding strategies. We start with five deductive frames proposed by Erjavec and Erjavec (2021), and new frames can be derived from the data. The deductive frames are the societal concerns frame, the farmers’ economic frame, the policy mechanism frame, the foreign trade frame, and the budgetary frame. The key concepts and keywords proposed by Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) inform the codes developed and applied for the analysis. The societal concerns frame is constructed from societal issues and is predominantly summarised by the keywords “greening”, “food security, safety, quality, and sustainability”, and “green growth” (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The farmers’ economic frame revolves around farmers’ private interests such as sufficient farm income, generational renewal, or a fair standard of living for farmers. The keywords describing the farmers’ economic frame are “viable food production”, “fair farm income” and “risk management” (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). These keywords can also be found in some of the general CAP objectives such as “to increase agricultural productivity” and “to ensure a fair standard of living for farmers” (European Council 2022). The policy mechanism frame is composed of the keywords “policy instruments”, “policy implementation” and “overall architecture”. It is used to highlight the implementation of the objectives and policy implications of the CAP reform (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The foreign trade frame is constructed around market and trade orientation and the competitiveness of farmers at national, EU and international level. The keywords used for the foreign trade frame are “international trade”, “competitiveness” and “market orientation” (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021), referring to the CAP objective of “stabilising agricultural markets” (European Council 2022). The budgetary frame is composed of the keywords “budget”, “expenditure” and “legitimisation of the CAP” and is constructed around the CAP budget and its distribution between the member states and the two pillars of the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021).

We follow three major steps for develo** the codebook. First, we read a sample of 100 newspaper articles, apply the deductive codes based on Erjavec and Erjavec (2021), inductively develop new codes and revise the codebook. Second, similar codes are merged, and codes are combined into code categories. Third, we conduct a trial round on another 100 newspaper articles to test the revised codebook and to develop subframes. We create subframes by identifying framing devices, that are operationalised by key concepts and keywords, and frame elements. The codebook is refined based on the experienced challenges.

Then, we code a total of 1,155 newspaper articles in four rounds. First, we read the newspaper article and take descriptive notes about the content. Second, we analyse the newspaper article for framing devices (i.e. key concepts and keywords). Third, the frame elements (i.e. problem definition, causal interpretation, treatment recommendation, moral evaluation) are assigned to the data material. Fourth, we read the newspaper articles again and assign frames and respective subframes. These four rounds are applied consecutively for each newspaper article.

The most important coding rules can be described as follows. First, a specific pattern must be identified across multiple newspaper articles to qualify as a frame (Matthes 2007). Second, frames have to be public concerns because only then different points of view can be adopted (Matthes 2007). Several frames may occur in one newspaper article. However, not every newspaper article has to contain a frame. Third, the frames are linked to actors or actors’ statements. Hence, the main actors have to be coded (Entman 1993; Matthes 2007), and at least one actor must comment on the public concern and address at least two frame elements. We code a maximum of three actors per newspaper article. The coded actors are most important in terms of content, i.e. their interests or opinion take up most space in the newspaper article. If no actor is evident or if the journalist is the causal attributor, the journalist may also be coded as actor (Matthes 2007). Fourth, we code the individual frame elements for reasons of reliability and following the suggestion of several authors (Früh 2001; Kohring and Matthes 2002; Matthes and Kohring 2004). Coding decisions are discussed in the research team after every coding step to ensure a common understanding, resolve possible ambiguities and reach agreement on the application of the codes.

By following the described coding rules, we analyse the newspaper articles using the qualitative content analysis software ATLAS.ti and taking into account framing devices (Gamson and Modigliani 1989) and frame elements (Entman 1993). The codes linked with the frame elements are attributed to the respective actor. The four frame elements are theoretically derived, but the codes are developed based on the data material (Matthes 2007). After the coding process, we use ATLAS.ti’s data analysis tools (i.e. code co-occurrence, code document table, query tool) to iteratively compare and identify interlinkages between coded text passages. We analyse the newspaper articles in a random order to avoid that potential learning effects are reflected over time (Wirth 2001). Moreover, we analyse the number of occurrence and the distribution of frames over time. We translate direct quotes into English and use them as examples in the results section. The assigned alpha-numerical codes (e.g. D3258) after each quote in the results section refer to the random order of the newspaper articles that were assigned automatically in ATLAS.ti.

Results

Frames of the CAP reform 2013 used in Austria’s agricultural media

Five frames and 25 subframes are identified in the data material (Table 2). They are presented by their number of occurrence in the 1,155 analysed newspaper articles of the Bauernzeitung.

Policy mechanism frame

The policy mechanism frame is mainly composed of keywords such as “dairy quotas” or “cross-compliance”. It is applied by the EC, EP and Council of the European Union to describe the proposed policy instruments and underpin the professionalism and importance of these policy instruments. The keywords are composed of technical terms and majorly address agricultural experts. The often-lamented powerlessness against "those up there in Brussels" (D3258) is also expressed in this frame. It is not referring to a specific CAP objective. However, it is used to describe the implementation of the CAP’s objectives in general. Nine subframes are found which are described in the appendix. The rural development subframe is explained as one example in the following.

The rural development subframe is constructed around the “Pillar II”, the “agri-environmental programme” and other “rural development measures”. Austria has one of the most extensive rural development programmes in the EU, in terms of money spent, with high relevance in national agricultural policy making processes. National actors largely use this subframe in order to demonstrate Austria’s progress in achieving the environmental objectives outlined in the rural development programme. The EC and the EP also use this subframe frequently. For instance, an Austrian member of the EP emphasises that more than 7,000 amendments to the CAP legislative texts are to be negotiated in the trilogue:

“The rural development programme stands for green growth and competitiveness. It has been “the fuel” for progress in rural areas in Austria in the past. The rural development programme secures jobs, invests in innovative projects, and keeps rural areas open and attractive and therefore needs sufficient budget.” (D1194)

This is an illustrative example of the frame elements. The actor is an Austrian member of the EP. The rural development programme with its measures defines the topic addressed. The budget spent in Pillar II is seen as the reason for the progress in rural areas in Austria. Maintaining the budget for rural development measures is the recommended solution, and moral evaluation of the rural development programme by the actor is positive.

Farmers’ economic frame

The farmers’ economic frame expresses the importance of aligning the CAP with the farmers’ need to generate regular income. Keywords such as “conditions of small farmers”, “generational renewal” or “viable food production” are used to emphasise that agricultural activities need to ensure a fair living standard for farmers, which is closely related to the respective CAP objective. The farmers’ economic frame is pushed by farmers’ interest groups, who are constantly present in agricultural policy making processes in Brussels. We have identified six subframes within this frame, which are summarised in the appendix. Exemplarily, the investment subframe is outlined below.

Mainly farmers’ interest groups use the investment subframe. They highlight the importance of farm investments for the viability of farms and for progress in the agricultural sector. They further argue that agricultural investments are beneficial for rural areas and that an increase in investment support will strengthen farmers’ willingness to invest. They suggest that the investment support shall be combined with standards for improving competitiveness and farm productivity. Overall, investments in the agricultural sector have increased in Austria since the last CAP reform. However, the situation is slightly different in pig farming, as illustrated by a representative of the farmers’ interest group:

“In pig farming, we are facing an investment freeze due to uncertainties in animal welfare standards. This is the most acute and intolerable issue in Austrian agricultural policy that is calling for a solution. De-bureaucratisation and planning security for farmers are key.” (D833)

The frame elements related to pig farming are as follows: A representative of the farmers’ interest group defines investment freeze as the problem. Uncertainties in animal welfare standards are made responsible for this situation. De-bureaucratisation and increasing planning security for farmers are recommended as solutions and moral evaluation by the actor is negative.

The Austrian agricultural minister is more positive regarding investments in Austrian agriculture:

"Rural areas are the main advantage of Austria and create quality of life. For farmers, but also for society. Investments in rural areas are therefore a genuine provision for the future. Vital, competitive, and lively regions are the main concern of my agricultural policy with a strong focus on investment support.” (D1637)

The problem defined is to maintain quality of life in rural areas. The actor is the Austrian agricultural minister. The solution proposed are investments in rural areas and moral evaluation is positive.

Societal concerns frame

The societal concerns frame is formed around the notion of human-nature relationships. Examples of these relationships include the use of renewable energies expressed in the environment subframe or agri-food products expressed in the food security and quality subframe. It is pushed by environmental NGOs and has gained in importance in the EC strategic paper 2010 on the CAP reform 2013. The most common expressions of this frame are the prioritisation of environmental protection and climate change mitigation. This frame comprises of five subframes, as summarised in the appendix. The environment subframe occurs most often in the analysed newspaper articles and is described below.

The environment subframe highlights the beneficial and adverse environmental effects of agricultural production. Primarily, it enjoys popularity among environmental actors such as environmental NGOs but also agricultural actors such as farmers, farmers’ interest groups or actors from agricultural industry use this subframe more often, albeit agricultural actors use it differently than NGOs. On the one hand, farmers feel overwhelmed by restrictions with potentially pro-environmental effects. Farmers’ interest groups call for practical solutions that enable agricultural production. On the other hand, NGOs warn of just another greenwashing of the CAP without significant environmental improvements. They describe monocultures, intensive livestock farming, and pesticide use to increase output as contra-productive to improve environmental quality. While some Austrian actors – such as federal state politicians – use the environment subframe to advertise for greening, others use it to emphasise the risk of undermining national agri-environmental programmes, as expressed in the following quote by a member of the Austrian farmers’ interest group:

“Meanwhile, EU member states remain sceptical, and so does Austria. In this country, there are fears not only that the greening measures will lead to more bureaucracy, but also that the entry threshold for the Austrian agri-environmental programme ÖPUL will finally become higher.” (D895)

The topic expressed in this quote is greening. Bureaucracy and the stricter entry threshold for the agri-environmental programme are made responsible for the negative attitude towards greening. A solution proposed is to keep the greening requirements low. Overall evaluation is negative.

According to an environmental NGO, the CAP reform proposal falls short to realise environmental expectations and achieve environmental objectives, especially in the area of greening.

“The regulation is regarded inadequate. With the draft proposals, greening cannot develop its positive effects on soil quality, biodiversity, climate protection and kee** waters clean.” (D737)

The topic addressed is greening and evaluation is negative. The reasoning behind is that the proposal is too lenient and doing little good to the environment. The environmental NGO proposes to make greening subject to stricter requirements.

Budgetary frame

This frame is constructed around the CAP budget, its share of the total EU budget and its distribution between member states. While the financial framework was included in the EC strategic papers in the past, it has been provided separately since the multi-annual financial framework in 2010 (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The budgetary frame is mainly pushed by the European Council who adopts the EU budget together with the EP, after the EC proposal. The EC emphasises the provision of public goods to legitimise CAP payments. Besides this public goods subframe described below, it consists of the financial regulations subframe, as outlined in the appendix.

The public goods subframe refers to societal benefits of the CAP and the provision of public goods. In its extreme form, actors using this subframe ask for disclosing the payees and the received payments in the transparency database. The subframe is used by Austrian NGOs and the European Court of Auditors postulating that the CAP must be targeted to the needs and expectations of EU citizens. The proposed solution is that services expected from agriculture and offered to the public must be paid by the public. However, society is willing to support agriculture only if it is aware of the services provided by farmers. The Austrian agricultural minister underlines:

“The agricultural sector is not a welfare recipient. Instead, farmers are compensated for the diverse services they offer to the public. Austrian agriculture enables that we have affordable food, a cultivated landscape, clean water, and air. For us, to continue to have these services, there needs to be sufficient support for farmers.” (D398)

The frame elements of this example can be summarised as follows. The actor is the Austrian agricultural minister. Public money for public goods defines the topic addressed. Austrian farmers are seen as the reason for affordable food, cultivated landscape and clean water and air. Maintaining subsidies for Austrian farmers is the recommended solution, and moral evaluation is positive.

Foreign trade frame

The foreign trade frame is mainly pushed by multi-national trade negotiations and agreements. The main characteristics of this frame are “market and trade orientation” as well as “global and domestic competitiveness”. The frame also refers to the interaction of actors on the market. While the foreign trade frame played a major role in the past EC strategic papers, it is less important in the CAP reform 2013 (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The following paragraph describes the competitive subframe. The other two subframes are summarised in the appendix.

The competitiveness subframe refers to global and domestic competitiveness within the EU. Domestic competitiveness is widely discussed in the analysed newspaper articles after the abolition of the milk and sugar quotas. In addition, there is a strong focus on how to improve competitiveness of small-scale agriculture in Austria. While the EC argues that the abolition of the quotas strengthens agricultural competitiveness, agricultural industry representatives value the abolition as sharp decline in competitiveness. The proposed solution by agricultural industry is to offer sufficient programmes and money for farmers such that they can compete internationally. In the analysed newspaper articles, competition is often mentioned together with innovation. The president of the Austrian farmers’ interest group calls the domestic dairy industry to prepare for the expiration of the milk quota system on 31 March 2015:

“The domestic quantity of milk, after the quota system expires, is expected to increase by around 15 percent. An export offensive is needed to help bring this additional quantity on the world market.” (D2462)

The president of the Austrian farmers’ interest group addresses the end of the milk quota system. He recommends launching an export offensive for the expected additional quantity of milk. His overall evaluation of the topic is negative.

Development of the frames in Austria’s agricultural media during the CAP reform process 2013

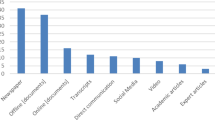

Figure 1 illustrates the number of occurrence of the five frames in the 1,155 newspaper articles addressing the CAP reform process between 01/10/2010 and 31/01/2015 in the Austrian Bauernzeitung. Seven key events are identified in the reporting period that brought about changes in the used frames and subframes: (i) publication of the EC strategic paper in November 2010, (ii) EC proposal on the four basic regulations in October 2011, (iii) start of negotiations on the multi-annual financial framework in November 2012, (iv) political agreement of EC, EP and Council in June 2013, (v) commitment to 50% national co-financing in September 2013, (vi) publication of the CAP regulations in the EU Official Journal in December 2013 and (vii) submission of the Austrian rural development programme to the EC in April 2014. The key events and how they relate to the media coverage at these points in time are described in more detail below.

-

(i) Publication of the EC strategic paper, November 2010

The EC published the strategic paper outlining the direction and objectives of the CAP reform 2013 on 10 November 2010. At this time, the policy mechanism frame is dominant in the agricultural newspaper articles, followed by the farmers’ economic frame and the budgetary frame. After this event, media coverage slightly decreases until the budgetary frame reaches a new peak in July 2011. As noted in the newspaper articles, the Romanian EU agriculture commissioner's strategic paper suggested less radical changes than previous ones. The financial structure of the CAP 2014–2020 remained completely open; no figures were mentioned in the EC strategic paper.

-

(ii) EC proposal on the four basic regulations, October 2011

Discussions on the CAP reform start with the publication of the EC proposal, with the policy mechanism frame occurring most often. In addition, the farmers’ economic frame and the societal concerns frame reach a peak. At the same time, discussions on the EU budget (applying the budgetary frame) decrease.

-

(iii) Start of negotiations on the multi-annual financial framework, November 2012

The budgetary frame is applied most often after the start of the negotiations on the multi-annual financial framework. It is followed by the policy mechanism frame and the farmers’ economic frame. Both increase in number of occurrence in the newspaper articles, compared to the previous years. The Austrian farmers’ interest group agreed with the federal chancellor and vice-chancellor that Austria would decline any further cuts in EU agricultural budget in the preparation phase of the special financial summit of the European Council in Brussels on 22 and 23 November 2012.

-

(iv) Political agreement of EC, EP and Council, June 2013

The budgetary frame and the societal concerns frame show similar development trends at the beginning of 2013, with the budgetary frame being used slightly more often than the societal concerns frame. A frame shift is apparent in March 2013. The societal concerns frame gains in importance, reaching its peak in July 2013, right after the political agreement of the EC, the EP, and the Council of the European Union. The farmers’ economic frame and the societal concerns frame keep a balance throughout the CAP reform process, indicating that agricultural and non-agricultural actors’ interests are given a voice. Also, the headlines of the newspaper articles highlight the hard trilogue negotiations: "difficult negotiations on the EU agricultural reform" (D1688), "fierce tug-of-war over the reform" (D623) or "the devil is still in many details" (D110). The EC, EP, and Agriculture Council fixed the CAP 2014–2020 between 24 and 26 June 2013, after three years of tough negotiations. In absolute terms, the farmers’ economic frame is used most often between the key events (iv) and (v).

-

(v) Commitment to 50% national co-financing, September 2013

The farmers’ economic frame reaches its peak in September 2013, when 50% national co-financing is agreed. This coincides with the national assembly elections and the Austrian conservative party campaigns for farmers' votes. In the media, the conservative party, as supporter of the Austrian farmers and opponent of additional taxes, and the social-democratic party, as advocate of excessive environmental protection, animal welfare and property taxes, fight a strong argumentative battle. The discussions centre on the "Faymann taxes", synonymous with property taxes suggested by the chancellor of the social-democratic party, which would have hit Austrian farmers hard.

The societal concerns frame also reaches its peak, excessively used by Austrian NGOs such as animal welfare organisations. Diverse topics are addressed, and farmers active in politics are directly attacked. For instance, reports on stables of politicians are published that reveal abuses in intensive livestock farming. The social-democratic party uses these revelations for its election campaign. In particular, the chancellor of the social-democratic party suggests cooperating with NGOs to work on environmental protection and animal welfare standards.

-

(vi) Publication of the CAP regulations in the EU Official Journal, December 2013

The EP adopted the EU agricultural policy on 20 November 2013, which was the basis for publishing the regulations for the CAP period 2014–2020 in the EU Official Journal a month later. During this time, the policy mechanism frame clearly dominates, followed by the farmers’ economic frame. After difficult and lengthy negotiations between the social-democratic party and the conservative party, cuts in national agricultural subsidies are averted and the coalition agreement determines: no new taxes for farmers, implementation of an Austria-wide uniform regional model without production-related payments for arable land, permanent crops and grassland, differentiation of payments according to land use, livestock-related payments for alpine pasture grazing, attractive small farmer scheme, support for young farmers, 50% national co-financing of rural development measures, increase in investment support, compensatory allowance for mountain farmers, and a legally approved solution to the map** of alpine pastures. At this time, the foreign trade frame, and in particular the trade orientation subframe, are used more often than during other stages though still at a comparably low level. They refer to the discussions on the free trade agreement with the United States.

-

(vii) Submission of the Austrian rural development programme to the EC, April 2014

The Austrian rural development programme for the period 2015 to 2020 was submitted to the EC in mid-April 2014. It focuses on the agri-environmental programme, investment support, mountain farming support and the LEADER programme. The assessment of the draft programme is ambivalent, as summarised by the president of a regional farmers' interest group:

“The new rural development programme is usable, but not a reason to cheer. Area measures will see a drop of 11 percent, while non-area measures will increase by almost 17 percent.” (D2495)

However, some actors praise the submitted rural development programme. At this last stage of the reform process, another frame shift can be identified. While the policy mechanism frame reaches its peak, the farmers’ economic frame decreases in occurrence. The societal concerns frame even outperforms the farmers’ economic frame.

Discussion

Frames and subframes in the agricultural policy context

Our analysis reveals that the five frames found by Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) are used in national reporting on the CAP reform 2013 in the Austrian Bauernzeitung as well. Moreover, we identify 25 subframes.

The policy mechanism frame is used most often, with varying numbers of occurrence along the stages of the CAP reform process. We identify nine subframes, including subframes with mainly national interest. This indicates that subframes are specified and adopted to the target groups of national media. The rural development subframe occurs more often than the direct payments subframe and addresses all key objectives of Pillar II. This might be specific to Austria, where about two thirds of the total CAP budget goes to Pillar II of rural development. In other member states only 25 percent go to Pillar II, on average (Hofreither and Sinabell 2014).

The farmers’ economic frame revolves around the notion that the current agricultural practices work very well. It is linked to three of the four CAP objectives, namely, to increase agricultural productivity, to ensure a fair standard of living for farmers and to provide agricultural products at reasonable prices. We find that the technology subframe is applied in favour of intensive farming and GMO use. However, we observe that this subframe does not imply a pro- or anti-environmental attitude. Rather, farmers and farmers’ interest groups present technological innovations as solutions to increase agricultural productivity and reduce adverse environmental effects of agricultural production. Similarly, Medina and Potter (2017) found that farmers’ interest groups build on the productivist discourse while, at the same time, consider environmental aspects. Hence, farmers’ interest groups are trying to influence CAP reforms by promoting sustainable intensification (Medina and Potter 2017). In our analysis, investments are evaluated positively by the agricultural minister and negatively by a representative of the farmers’ interest group. The latter evaluates the current system for receiving investment support negatively and asks for investment support that is easily accessible for farmers with low bureaucracy and high planning security.

Among the subframes of the societal concerns frame, the environment subframe is expressed most often in the Bauernzeitung, followed by the food security and quality subframe. In our analysis, supporters of the environment subframe address agricultural greenhouse gas emissions and their negative effect on the global climate. They urge to reduce farming intensity and thus emissions. Although both, agricultural actors such as farmers, farmers’ interest groups or actors from agricultural industry, and environmental actors, such as animal welfare organisations or environmental NGOs, use the environment subframe in the Bauernzeitung, they propose conflicting solutions, especially when it comes to agricultural productivity. Environmental NGOs emphasise that rising temperatures, deforestation, and unsustainable land use threaten our food security and propose to promote extensive farming to prevent biodiversity loss and water pollution. Austrian agricultural interest groups, however, refer to food security to argue for intensification. Similarly, Candel et al. (2014) demonstrate that a range of actors refer to food security to strengthen their policy positions but frame it in conflicting ways during the CAP reform debate post-2013. In our analysis, the societal concerns frame suggests that environmental problems can only be handled with joint efforts engaging all actors or as Isaac and de Loë (2022) call for an “all hands-on deck” societal effort. Several Austrian actors use the environment subframe to advertise greening positively or negatively. Hence, the proposed solutions are conflicting. Agricultural actors evaluate the greening requirements negatively because they would reduce agricultural production and therefore, they propose to keep greening requirements low. Some environmental actors evaluate greening negatively in our analysis because it would fail to improve environmental conditions. Others evaluate greening positively because it affects all farmers who receive direct payments and thus would have a great impact on the environment.

The budgetary frame deals with legitimising the CAP and its budget. This frame consists of the financial regulations subframe and the public goods subframe. Both enjoy high visibility throughout the reform process in Austria, with the financial regulations subframe being used a bit more often. Similar to the findings of Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) and Erjavec and Erjavec (2014), the analysed newspaper articles show that the EC puts more and more emphasis on the provision of public goods to legitimise CAP payments. This becomes apparent because the EC uses the public goods subframe more often than the financial regulations subframe. In our study, agricultural and environmental actors propose similar solutions, namely to increase the CAP budget to ensure the provision of public goods. Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) also describe an increasing need for legitimisation because of the declining share of the CAP in the total EU budget. Beside the public goods subframe, the need for explaining the CAP is also reflected in the increasing relevance of the societal concerns frame (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The exit of the United Kingdom as net contributor to the EU budget and other EU policies gaining in weight put further pressure on the EU budget (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) interpret the strengthening of the public goods subframe as a “hidden” effort for maintaining the CAP budget.

In our study, the foreign trade frame comprises of the trade orientation subframe, the competitiveness subframe, and the market orientation subframe. The competitiveness subframe is mainly constructed around the abolition of the milk and sugar quotas, with diverging arguments. In the analysed newspaper articles, the EC defends the abolition of the quotas because it strengthens the competitiveness of agriculture. The agricultural industry representatives consider the abolition as a sharp decline in agricultural competitiveness. The proposed solution is to offer comprehensive support programmes and foster innovation to make Austrian small-scale agriculture internationally competitive. This is in line with Bragdon and Smith (2015) who argue that farmers’ innovation capacity needs to be increased to meet the challenges posed by the global agri-food system.

Development of frames over time in the CAP reform process

Since the implementation of the CAP in the 1960ies, the policy mechanism frame has been reframed such that member states are made responsible for the content and implementation of the CAP (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021). The EC is now guiding the reforms instead of specifying their details (Bickerton et al. 2014). Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) note that this development could indicate the CAP’s marginalisation for the benefit of other EU policy fields including migration and digitalisation. Another explanation might be the increasing power of member states compared to the EU institutions, also referred to as new intergovernmentalism (Bickerton et al. 2014).

In our analysis, the farmers’ economic frame is rather stable regarding its number of occurrence. Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) interpret this as an indicator of the continuous farm lobbies’ power and their influence, in particular on conservative member states and EP members. Our results also show that national farmers’ interest groups are powerful in framing the CAP reform 2013 in Austrian agricultural media. We find that the use of the farmers’ income subframe decreases over time, whereas the social balance subframe and the productivity subframe gain in importance. One possible explanation is that securing farm income is undisputed and therefore less covered in the newspaper articles, whereas productivity aspects such as increasing agricultural output and social aspects such as farm succession are more discussed between agricultural and environmental actors. During the reform process, the farmers’ economic frame and the societal concerns frame occur most often in the Bauernzeitung in September 2013, when 50% of national co-financing was agreed. However, the national election campaign took place at that time and likely influenced the number and occurrence of frames and subframes. This indicates that EU and national politics are not clearly separated in communication processes in the agricultural media.

The occurrence of the societal concerns frame has increased in the largest Austrian agricultural newspaper during the CAP reform process 2013. Similarly, Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) report an increasing importance of the societal concerns frame (i.e. it dominates in the documents) throughout the CAP reforms since its early beginnings. Beside the environment, other societal concerns such as food quality or animal welfare have increased in relevance and are addressed in the Bauernzeitung. Moreover, we find that the image subframe is gradually mentioned and that it is constructed around the idea of raising public awareness for domestic and sustainable food production. Lindgren et al. (2018) also call for a shift towards sustainably produced food.

Frame coverage reaches its peak immediately after the start of the special summit on the multi-annual financial framework in the national agricultural medium. The budgetary frame occurs most often, followed by the farmers’ economic frame and the policy mechanism frame. Our analysis reveals that the budgetary frame remains important throughout the CAP reform process indicating that the CAP is a financially and politically important policy field in the EU.

The foreign trade frame remains at constantly low level throughout the CAP reform process in Austria. Overall, its importance has decreased in the CAP through the liberalisation of agricultural markets (Erjavec and Erjavec (2021).

Actors applying the frames

Our analysis suggests that framing is an important tool to influence the policy process. We find that various powerful actors such as agricultural politicians and agricultural interest groups – intentionally or unintentionally – drive the media debate in their favoured direction. This is in line with previous research which shows that agricultural industries influence policy processes (Fuchs et al. 2011; Isaac and de Loë 2022; Montpetit 2002; Montpetit and Coleman 1999). Moreover, our analysis reveals that politicians rely not only on notions and ideas but also on the strategic choice of certain, often positive, words and phrases that appear repeatedly in the analysed newspaper articles. In general, positively connoted words and phrases seem to be a popular framing strategy (Isaac and de Loë 2022).

Our study shows that mainly the EC, the EP, and the Council of the European Union use the policy mechanism frame, and that mainly farmers and farmers’ interest groups apply the farmers’ economic frame. Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) find that the societal concerns frame is largely used by environmental NGOs, whereas our findings suggest that agricultural actors such as farmers’ interest groups use the societal concerns frame most often. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that mainly the European Council applies the budgetary frame, and that the foreign trade frame is pushed by multi-lateral trade negotiations such as the negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Our results also show that actors may use the same frame in different contexts. For example, farmers’ interest groups apply the food security and quality subframe when talking about food waste. They also apply this subframe to demonstrate the peculiarities of producing quality products in Austria. This is in line with Candel et al. (2014) who show that the EC deploys the food security frame in different contexts to mobilise public support for the reformed CAP. Moreover, Van Gorp and van der Goot (2012) claim that different actors sometimes use the same frame to support opposing forms of food production. Our analysis also shows that both, members of the social-democratic party and members of the conservative party, use the animal welfare subframe to support different forms of animal husbandry. For instance, the Austrian health minister from the social-democratic party, who is responsible for animal welfare in Austria, uses this subframe to call for more animal welfare in that he plans a ban on box stalls for breeding sows. By contrast, the Austrian agricultural minister from the conservative party emphasises that Austria already has the highest animal welfare standards in the EU, and this ban would force many pig farmers to cease farming. Hence, he calls for fewer regulations in animal husbandry.

Our analysis shows high numbers of occurrences of the farmers’ economic frame and the societal concerns frame indicating a compromise between various actors in the CAP reform process 2013. Similarly, Erjavec and Erjavec (2014) note that both the environmental and productivity-oriented discourses are strengthened in the CAP reform 2013. Furthermore, the number of occurrences of the farmers’ economic frame and the societal concerns frame develop similarly over time in the Austrian agricultural newspaper, suggesting that non-agricultural actors tend to response to agricultural actors.

Method applied for framing agricultural policy processes

Frames can be interpreted as the result of complex policy processes (Erjavec and Erjavec 2021) which can be analysed in a structured way (Entman 1993). The chosen method proved useful to identify frames applied in the agricultural policy process at EU level and reproduced in national agricultural newspapers, to explore frame-actor relationships, and to study subframes as well as their changes over time.

The main limitation of our analysis is its focus on the agricultural newspaper Bauernzeitung, which mainly addresses farmers and agricultural policy makers. Kaiser (2023) shows that the frequency of occurrence of certain topics and the storyline differs between agricultural newspapers and mainstream newspapers. Our analysis could thus be expanded to integrate additional newspapers, TV, and radio reports to cover the public discourse as well. Moreover, future studies may look at actors and actor coalitions in more detail. By expanding the analysis to other media, we may see whether daily or weekly newspapers reaching the general public apply the same frames as agricultural newspapers and whether the cited actors are similar. We might expect that the five frames are also addressed in other media, whereas the subframes might vary across the type and periodicity of the selected media.

Conclusions and policy implications

National agricultural media present the CAP and its reform processes by referring to the messages framed by the main actors involved. Our qualitative content analysis of frames and subframes may provide useful insights for a diverse group of CAP actors – including agricultural and environmental actors as well as EU institutions – on how to target their communication strategy concerning content and timing. Erjavec and Erjavec (2021) find that the EC employs the societal concerns frame, the farmers’ economic frame, the policy mechanism frame, the foreign trade frame and the budgetary frame in the CAP strategic papers. Our analysis shows that these five frames are also used in the largest Austrian agricultural newspaper during the CAP reform process 2013 and that they consist of 25 subframes. Subframes are used and aligned to the target groups of the analysed national medium. The choice of the frames and subframes is an attempt of national actors to increase acceptance of the CAP through media reporting. The number of occurrence of specific frames is associated to specific events in the reform process or national debates on CAP-related issues. In Austria, the farmers’ economic frame is highly present during the CAP reform process 2013 showing the farm lobbies’ power to influence the CAP reform process. However, also the societal concerns frame increased over time indicating the societal interest in the CAP. Our analysis further shows that framing influences the debate, with potential implications for policy design, implementation, and outcome. To conclude, agricultural media generate support for or condemnation of agricultural policy among the readers and affect political agenda setting. Future research could focus on other CAP reforms and additional media to analyse whether the identified frames are prevalent in different reforms and media channels and whether additional subframes are employed.

Data availability

The dataset used for this analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of APA (Austrian press agency) only. The dataset is not publicly available and restrictions for sharing the dataset apply because it is used under license.

References

Bickerton, C.J., D. Hodson, and U. Puetter. 2014. The new intergovernmentalism. States and supranational actors in the post-Maastricht era, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bragdon, S.H., and C. Smith. 2015. Small-scale farmer innovation. Geneva: Quaker United Nations Office.

Buitenhuis, Y., J. Candel, K. Termeer, and P. Feindt. 2022. Reconstructing the framing of resilience in the European Union’s common agricultural policy post-2020 reform. Sociologia Ruralis 62 (3): 564–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12380.

Burkart, R. 2019. Kommunikationswissenschaft. Grundlagen und Problemfelder einer interdisziplinären Sozialwissenschaft, 5th ed. Stuttgart: UTB.

Candel, J.J., G.E. Breeman, S.J. Stiller, and C.J. Termeer. 2014. Disentangling the consensus frame of food security. The case of the EU common agricultural policy reform debate. Food Policy 44: 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.10.005.

Cloke, P. 1996. Looking through european eyes? A re-evaluation of agricultural deregulation in New Zealand. Sociologia Ruralis 36 (3): 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1996.tb00024.x.

Cunha, A., and A. Swinbank. 2011. An Inside View of the CAP Reform Process. Explaining the MacSharry, Agenda 2000, and Fischler Reforms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Daugbjerg, C., and A. Swinbank. 2007. The politics of CAP reform. Trade negotiations, institutional settings and blame avoidance. Journal of Common Market Studies 45 (1): 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00700.x.

Dermont, C., K. Ingold, L. Kammermann, and I. Stadelmann-Steffen. 2017. Bringing the policy making perspective in. A political science approach to social acceptance. Energy Policy 108: 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.062.

Entman, R.M. 1991. Framing U.S. coverage of international news. Contrasts in narratives of the KAL and Iran air incidents. Journal of Communication 41 (4): 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1991.tb02328.x.

Entman, R.M. 1993. Framing. Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

Erjavec, E., and K. Erjavec. 2014. “Greening” as justification for the kee** of the redistributional character of agricultural policy? Policy discourse of CAP 2020 reform. In The Common Agricultural Policy in the 21st Century, ed. E. Schmid and S. Vogel, 43–65. Wien: Festschrift für Markus F. Hofreither. Facultas Verlags- und Buchhandels AG.

Erjavec, K., and E. Erjavec. 2009. Changing EU agricultural policy discourses? The discourse analysis of commissioner’s speeches 2000–2007. Food Policy 34 (2): 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2008.10.009.

Erjavec, K., and E. Erjavec. 2015. ‘Greening the CAP’ – just a fashionable justification? A discourse analysis of the 2014–2020 CAP reform documents. Food Policy 51: 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.12.006.

Erjavec, K., and E. Erjavec. 2021. Framing agricultural policy through the EC’s strategies on CAP reforms (1992–2017). Agricultural and Food Economics 9(5). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-021-00178-4.

European Commission. 2013a. Overview of CAP Reform 2014–2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agri-policy-perspectives-brief-05_en.pdf. Accessed 08 Apr 2020.

European Commission. 2013b. Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005.

European Council. 2022. Feeding Europe. 60 years of common agricultural policy. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/60-years-of-common-agricultural-policy/. Accessed 17 Oct 2022.

European Parliament. 2020. Handbook on the Ordinary Legislative Procedure. A guide to how the European Parliament co-legislates. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/255709/OLP_2020_EN.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2022.

European Parliament. 2022. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the Treaty. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_3.2.1.pdf. Accessed 18 Oct 2022.

Ferree, M.M., W.A. Gamson, J. Gerhards, and D. Rucht. 2002. Sha** abortion discourse. Democracy and the public sphere in Germany and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Früh, W. 2001. Inhaltsanalyse. Theorie und Praxis, 3rd ed. Konstanz: UVK.

Fuchs, D., A. Kalfagianni, and T. Havinga. 2011. Actors in private food governance. The legitimacy of retail standards and multistakeholder initiatives with civil society participation. Agriculture and Human Values 28: 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9236-3.

Gamson, W., and A. Modigliani. 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power. A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95 (1): 1–37.

Goffman, E. 1980. Rahmen-Analyse. Ein Versuch über die Organisation von Alltagserfahrungen, 2nd ed. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

Hallahan, K. 1999. Seven models of framing. Implications for public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research 11 (3): 205–242. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1103_02.

Hofreither, M.F., and F. Sinabell. 2014. Common Agricultural Policy 2014 to 2020. https://www.wifo.ac.at/jart/prj3/wifo/resources/person_dokument/person_dokument.jart?publikationsid=47173&mime_type=application/pdf. Accessed 10 May 2022

Ingold, K. 2011. Network structures within policy processes. Coalitions, power, and brokerage in swiss climate policy. Policy Studies Journal 39 (3): 435–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00416.x.

Isaac, B., and R. de Loë. 2022. Exploring the influence of agricultural actors on water quality policy. The role of discourse and framing. Environmental Politics 31 (4): 598–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1947634.

Kaiser, A. 2023. Discursive struggles over pesticide legitimacy in Switzerland. A news media analysis. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 49: 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100777.

Kasparek-Koschatko, V., J.A. Jungmair, P. Wieser, B. Kapp, and S. Pöchtrager. 2020. The representation of the common agricultural policy in the media. A qualitative content analysis of Austrian daily newspapers based on the framing theory. Austrian Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Studies 29 (26): 225–232.

Kohring, M., and J. Matthes. 2002. The face(t)s of biotech in the nineties. How the german press framed modern biotechnology. Public Understanding of Science 11 (2): 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/11/2/304.

Kriesi, H., and M. Jegen. 2001. The swiss energy policy elite. The actor constellation of a policy domain in transition. European Journal of Political Research 39 (2): 251–287. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011032228323.

Liepins, R., and B. Bradshaw. 1999. Neo-Liberal agricultural discourse in New Zealand economy, culture and politics linked. Sociologia Ruralis 39 (4): 563–582. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9523.00124.

Lindgren, E., F. Harris, A.D. Dangour, A. Gasparatos, M. Hiramatsu, F. Javadi, B. Loken, T. Murakami, P. Scheelbeek, and A. Haines. 2018. Sustainable food systems. A health perspective. Sustainability Science 13 (6): 1505–1517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0586-x.

Matthes, J. 2007. Framing-Effekte. Zum Einfluss der Politikberichterstattung auf die Einstellungen der Rezipienten. München: Verlag Reinhard Fischer.

Matthes, J., and M. Kohring. 2004. Die empirische erfassung von medien-frames. M&K 52: 56–75. https://doi.org/10.5771/1615-634x-2004-1-56.

Mayring, P. 2002. Einführung in die qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Anleitung zu qualitativem Denken, 5th ed. Weinheim: Beltz.

Medina, G., and C. Potter. 2017. The nature and developments of the common agricultural policy. Lessons for european integration from the UK perspective. Journal of European Integration 39 (4): 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1281263.

Montpetit, É. 2002. Policy networks, federal arrangements, and the development of environmental regulations. A comparison of the Canadian and American agricultural sectors. An International Journal of Policy, Administrations, and Institutions 15 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0491.00177.

Montpetit, É., and W.D. Coleman. 1999. Policy communities and policy divergence in Canada. Agro-environmental policy development in Quebec and Ontario. Canadian Journal of Political Science 32 (4): 691–714. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423900016954.

Nègre, F. 2022. Financing of the CAP. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ftu/pdf/en/FTU_3.2.2.pdf. Accessed 21 Nov 2022.

Potter, C. 2006. Competing narratives for the future of european agriculture. The Agri-environmental consequences of neoliberalization in the context of the Doha round. The Geographical Journal 172 (3): 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00210.x.

Potter, C., and M. Tilzey. 2005. Agricultural policy discourses in the european post-fordist transition. Neoliberalism, neomercantilism and multifunctionality. Progress in Human Geography 29 (5): 581–600. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph569oa.

Reeh, M. 2015. The evolution of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) with respect to markets and direct payments. In Insights into Austrian agriculture since EU accession, ed. Bundesanstalt für Agrarwirtschaft, 21–34. Wien.

Simantov, A., ed. 1973. Economic, Social and Political Priorities in Agricultural Policy Formulation in Industrialized Countries. Sao Paulo: International Association of Agricultural Economists.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1981. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science 211: 453–458.

Van Gorp, B. 2010. Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis. In Doing news framing analysis. Empirical and theoretical perspectives, ed. P. D‘Angelo and J. Kuypers, 84–89. New York: Routledge.

Van Gorp, B., and M.J. van der Goot. 2012. Sustainable food and agriculture. Stakeholder’s frames. Communication, Culture & Critique 5 (2): 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-9137.2012.01135.x.

van Lieshout, M., A. Dewulf, N. Aarts, and C. Termeer. 2013. Framing scale increase in Dutch agricultural policy 1950–2012. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 64–65 (1): 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2013.02.001.

Wirth, W. 2001. Der codierprozess als gelenkte rezeption. Bausteine für eine theorie des codierens. In Inhaltsanalyse Perspektiven, Probleme, Potentiale, ed. W. Wirth and E. Lauf, 157–182. Köln: Halem.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding is provided by the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna (BOKU).

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). This work was supported by the research project LAMASUS, Land Management for Sustainability. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 101060423. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AO conceived of the study, prepared data for the analysis, performed the analysis and contributed to writing and editing. HM was involved in conceptualisation, discussion on the analysis, reviewing and supervision. ES was involved in the development of the concept and provided critical review and supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Subframes

Appendix: Subframes

Table 3

Policy mechanism frame

Negotiation subframe

The negotiation subframe is constructed around the EU policy and decision-making process, involving the EC, EP, Council of the European Union, and the European Council. It also addresses the communication between the EU institutions and the 27 member states. Most prominent are the controversial discussions and encountered difficulties to find compromises in the trilogue negotiations. These negotiations are typically taking place over more than three years.

National politics subframe

This subframe is constructed around national policy making such as changes in the agricultural flat rate scheme, farmers’ social security or national dairy or suckler cow premiums. The national alpine pasture reference system is subject to criticism during the CAP reform process 2013 in Austria. Difficulties in digitalising alpine pastures are experienced, as alpine pastures change yearly due to windthrow, scrub encroachment or rockfall, for example. Large deviations (of more the 50%) between the recorded and the actual extent of alpine pastures are found in random inspections, which jeopardise the entire reference database of agricultural parcels and thus the granting of all area payments.

Another pertinent concern during the reform process is the change in the agricultural flat rate scheme in Austria. The Austrian chamber of agriculture – the national farmers’ interest group – advertises for kee** as many farmers as possible in the agricultural flat rate scheme. By contrast, the Austrian chamber of labour – the national representation of employees’ interests – argues for ending tax privileges for farmers. Keywords that proponents of this subframe use are “envy discussions”, “class struggle” or “Faymann-taxes” (pointing to the Austrian chancellor of the social-democratic party at the time of the CAP reform 2013).

Rural development subframe

This subframe is constructed around Pillar II and addresses rural development measures and the entire process from programme submission until approval. Austria has one of the most extensive rural development programmes in the EU with high relevance in national agricultural policy making processes. The subframe is largely used by national agricultural actors to demonstrate Austria’s progress in achieving set environmental objectives. Interestingly, the rural development subframe plays a far more important role in terms of number of occurrence in Austria’s agricultural media discussions than the direct payments subframe.

Bureaucracy subframe

This subframe highlights bureaucratic procedures introduced by the civil service in Brussels that farmers have to follow and that are often perceived as hurdles. An example for this subframe is that the Austrian agricultural minister asks for a “twelve-point diet plan” (D275) for the EU agricultural bureaucracy:

“Away from duplication, standardisation, cross-compliance simplification measures and transparent, comprehensible systems. The opportunity should be taken now to specifically defuse bureaucracy in the CAP from 2014 onwards.” (D275)

This is also an illustrative example of the frame elements. The actor is the Austrian agricultural minister. The increasing bureaucracy at EU level defines the problem addressed. The cause of the problem is that there are more and more regulations, and standards that must be complied with and monitored. De-bureaucratisation and simplification are recommended solutions, and moral evaluation of the problem is negative. However, not only national actors complain about EU bureaucracy but also EU actors, such as the EU agricultural commissioner.

Direct payments subframe

This subframe refers to the idea that direct payments are and should remain an important income support for farmers. However, it also highlights that farmers cannot receive “a million euros” (D446) from direct payments because this would cause harm to the image of farmers. This subframe is only used by agricultural actors.

Pro-EU subframe

The pro-EU subframe refers to the benefits EU citizens may enjoy. “Brussels” (D3258) is often used as a metaphor for the entire EU regulatory system, including the EU institutions. The EC pro-EU framing strategy proves robust and stronger than the negative reports as illustrated by the contra-EU subframe described below. The following quote by an Austrian regional politician supports the EU:

“The common Europe is a project of peace. Young people are given special opportunities, we can travel freely, we have a common currency, and we can also rely on agricultural policy.” (D2422)

Common Market Organisation (CMO) subframe

The core premise of the CMO subframe is that public support is necessary for the agricultural sector. Most heavily discussed are the abolishment of milk and sugar quotas. While national agricultural politicians argue for the milk quota, the agricultural commissioner defends its abolishment as the EU should adjust itself to the projected demand growth in the world milk market:

“The milk quotas were introduced in an era of ‘butter mountains’ and ‘milk lakes’ in 1984. Today, the situation is completely different. Demand in the world dairy market is increasing and the medium-term outlook is positive in this respect.” (D3238)

Two pillar structure subframe

This subframe deals with the two pillars of the CAP. A member of the Austrian chamber of agriculture, for example, warns against changing the two pillar structure, as this would undermine programmes that are coordinated and have proven successful over many years:

“A greening component in Pillar I, as proposed by the commissioner for agriculture, would impair the competitive position towards third markets and thus weaken the possibility for a future agri-environmental programme.” (D145)

Another pending issue is shifting the payments for areas with natural or other specific constraints to Pillar I. It is critically evaluated by both, national and EU politicians.

Contra-EU subframe

The contra-EU subframe is constructed around the reasoning that the EU is responsible for instability and over-regulation, with the prominent example of the cucumber curvature. The line of argumentation is portrayed by a journalist:

“The most recent example is the attempt by commission officials to change the political agreement reached between EU member states and the EP on the content of the CAP reform in essential points. This is a disservice not only to European farmers, who finally need legal certainty, but also to the EU as a whole, as such actions fuel the already widespread scepticism about Europe.” (D1905)

While this journalist argues against the EU, the contra-EU subframe does not receive much attention during the CAP reform process 2013.

Farmers’ economic frame

Social balance subframe

Among the identified subframes, the social balance subframe occurs most often in the analysed data. It encompasses a wide range of topics, often focusing on “generational renewal”, “reducing inequalities”, “local employment”, “farm succession”, “female farmers”, “conditions of small farmers”, “family farms” and covering the CAP’s objective to “ensure a fair standard of living for farmers”. Proponents of the subframe also address the farmer’s position in the value chain and the increasing power of food retailers. The proposed solution is that market forces should be bundled on the producer side to strengthen farmers’ position in the value chain.

Productivity subframe

The productivity subframe is characterized by the keywords “productivity”, one of the CAP’s objectives “viable food production”, “increase in output” or “maintain agricultural food production”. Farmers and farmers’ interest groups use this subframe to demonstrate the importance to increase output. Moreover, they strictly reject the planned set-aside areas by the EC as part of greening in Pillar I. An agricultural actor puts it this way:

“We are not an agricultural Disneyland, we have to produce on 100 percent of the agricultural land." (D1428)