Abstract

Purpose

The incidence of invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis (iSDSE) infections is increasing in developed countries, but studies on the risk factors for death in iSDSE infections are scant. Here, we aimed to clarify risk factors and predictors of mortality in adults with iSDSE infections.

Methods

A multicentre observational study of adults with iSDSE infections was conducted to investigate the effects of host factors, disease severity, biomarkers, and antibiotic regimens, and bacterial factors on 28-day mortality.

Results

The overall mortality rate of 588 patients was 10.4%, with a significant increase in those aged ≥ 60 years. Most of the patients (97.4%) had underlying diseases. The mortality rate (70.4%) of patients with severe disease was significantly higher than that of patients with mild-to-moderate disease (4.3%; p < 0.001). The risk factors for death identified using multivariable analysis were age ≥ 60 years (hazard ratio [HR], 3.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0–11.3, p = 0.042); severe disease (HR, 15.0; 95% CI 7.7–29.2, p < 0.001); bacteraemia without primary focus (HR, 20.5; 95% CI 2.8–152.3, p = 0.003); serum creatinine ≥ 2.0 mg/dL (HR, 2.2; 95% CI 1.2–4.0, p = 0.010); serum creatine kinase ≥ 300 IU/L (HR, 2.1; 95% CI 1.1–3.8, p = 0.019); and macrolide resistance (HR, 1.8; 95% CI 1.0–3.3, p = 0.048). Treatment regimens and emm types were not associated with poor outcomes.

Conclusion

Evaluation of clinical manifestations and biomarkers on admission is important to predict invasive SDSE infection prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis (SDSE) was proposed as a new subspecies in 1996 [1]. SDSE isolated from humans as a commensal microorganism possesses antigens belonging to Lancefield group G, C, or A [2]. Although SDSE forms relatively large glossy colonies on blood agar that are strongly β-haemolytic, several biochemical property tests, such as the pyrrolidonyl arylamidase test, are required to distinguish SDSE from other haemolytic streptococci. Moreover, SDSE had been considered substantially less pathogenic than Streptococcus pyogenes (GAS). However, whole-genome sequencing has revealed that SDSE possesses several virulence factors. These factors include M protein (emm), streptokinase, C5a peptidase, hyaluronidase, and others involved in immune evasion, as demonstrated in GAS, and systemic toxicity of streptolysin O and streptolysin S [3, 4]. Thus, SDSE and GAS are considered closely related phylogenetically and may have originated from a common precursor [5].

SDSE was considered an asymptomatic coloniser of the human upper airway, skin, and gastrointestinal tract. Recently, it has been recognised as a clinically relevant pathogen that causes a broad range of diseases, from milder illnesses such as local skin and soft tissue infections to life-threatening conditions such as streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS) and necrotising fasciitis (NF), similar to those caused by GAS [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Invasive SDSE (iSDSE) infections are more common in older adults [12, 13] and individuals with underlying chronic diseases [7,8,9,10, 14, 15]. Consequently, the impact of disease burden associated with SDSE infections will grow in developed countries, which are aging rapidly.

Although studies have compared the onset age [16, 17], underlying diseases [7, 14,15,16], biomarkers [12], and mortality rates of iSDSE [7,8,9, 12, 14] with invasive GAS and invasive Group B streptococcal infections, only a few have clarified the risk factors for death in patients with iSDSE [17]. A common problem exists in that clinicians have limited awareness of the pathogenesis of SDSE. Therefore, we aimed to consolidate clinically relevant information on SDSE infections. We thus conducted this large-scale surveillance study of iSDSE infection in Japanese adults to evaluate the relative contribution of host factors, clinical manifestations, biomarkers, and bacterial factors to the 28-day mortality after admission.

Materials and methods

Study design

This retrospective cohort study involved a nationwide surveillance of iSDSE infections conducted from April 2010 to March 2016. One-hundred and thirty-six general hospitals with clinical microbiology laboratories throughout Japan participated in this study (Supplementary Fig. 1). During the study period, we received 686 strains derived from patients with iSDSE from the medical institutions. Ninety-eight patients (14.3%) were excluded from this study because of missing data (lack of basic information or loss on follow-up), and 588 (85.7%) cases were included for analysis.

SDSE isolates and patient definition

We identified patients aged ≥ 18 years with iSDSE infections. iSDSE infection was defined as the isolation of SDSE from normally sterile clinical samples such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, joint/synovial fluid, and closed pus. Strains submitted to our laboratory as SDSE from each institution were confirmed to belong to Lancefield Group A, C, or G using an agglutination test with latex agglutination reagent and re-identified according to the clinical microbiology manual. The Lancefield agglutination test results were 85.3% for group G, 12.8% for group C, and 1.9% for group A (emm type, stG485 and stG245), respectively. Eighty-six strains that agglutinated in group A or group C were confirmed to be SDSE by 16S rRNA sequencing.

Underlying chronic disease was defined as the presence of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, active cancer treated with anti-cancer therapy, kidney disease (severe or moderate reduction in glomerular filtration rate [GFR categories G4-5, or G3; KDIGO classification]), immunocompromised conditions, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, asplenia, congenital immunodeficiency, haematological diseases, and high dosage of medication such as systemic corticosteroids (daily dose of prednisolone equivalent to ≥ 10 mg/day for > 2 weeks) and biologics, liver disease, artificial joint replacement, and others. Disease severity was assessed using the diagnostic criteria of the guidelines for each disease [18,19,20,21] on admission.

Skin and soft tissue infections

The diagnostic criteria for severity assessment of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) are as follows [18]. For purulent SSTI, purulent skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs; abscess); for mild infection, incision, and drainage are indicated; for moderate infection, purulent infection with systemic signs of infection; for severe infection, incision and drainage plus oral antibiotics failed, and systemic signs of infection such as a temperature > 38 °C, tachycardia (heart rate > 90 beats per minute), tachypnoea (respiratory rate > 24 breaths per minute), or abnormal white blood cell count (> 12,000 or < 4000 cells/µL); or immunocompromised status. For non-purulent SSTIs, necrotising infection, cellulitis, or erysipelas; For mild infection, typical cellulitis or erysipelas with no focus of purulence; for moderate infection, typical cellulitis or erysipelas with systemic signs of infection; for severe infection, oral antibiotic treatment failed; systemic signs of infection (as defined above under purulent infection); immunocompromised status; or clinical signs of deeper infection such as bullae, skin sloughing, hypotension, or evidence of organ dysfunction.

Community-acquired pneumonia

The IDSA/ATS severity criteria [20] define severe community-acquired pneumonia as patients with either one of the following major criteria or three or more of the following minor criteria. Minor criteria are respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 250, multilobular infiltrates, confusion/disorientation, uraemia (blood urea nitrogen level > 20 mg/dL), leukopenia (white blood cell count < 4,000 cells/µL), thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/µL), hypothermia (core temperature < 36 °C), and hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation. Major criteria are septic shock with need of vasopressors and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Bacteraemia without primary focus and other invasive SDSE infections

The surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines [21] were used for evaluating bacteraemia without primary focus and other invasive SDSE infections. For mild sepsis, a life-threatening condition caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, resulting in organ dysfunction. The criteria for septic shock were circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities in patients with sepsis, presenting as fluid-refractory hypotension requiring vasopressor therapy with associated tissue hypoperfusion (lactate level > 2 mmol/L).

Antimicrobial susceptibility and emm ty**

Antibiotic treatment regimens were divided into five categories: penicillin, first- or second-generation cephalosporins, third-generation cephalosporins, carbapenems, and others. SDSE susceptibility to antimicrobial agents was determined using the agar-dilution method. We also analysed the pbp1a, pbp2x, and pbp2b genes, which encode penicillin-binding proteins associated with- β-lactam resistance, using DNA sequencing for each pbp gene. In parallel, three genes that mediate macrolide- and clindamycin resistance – mefA, ermA, and ermB – were identified by DNA amplification [22].

Ty** of emm encoding the M protein was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). After sequencing the amplified DNA fragments, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emm sequence database was used to identify the emm type (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/biotech/strepblast. asp).

Statistical analysis

Fatalities occurring within 28 days of admission were defined as deaths caused by or related to iSDSE infections. Categorical variables were tested using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Cutoffs for laboratory values were determined by the distribution of each biomarker. Relationships among death, patient attributes, and biomarkers were evaluated using logistic regression analysis to obtain odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), and p-values. Examined biomarkers were analysed as binary data after obtaining their cutoff values in advance using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. We also plotted the survival curve using Kaplan–Meier method and determined associations of disease severity, white blood cell (WBC) count, and other biomarkers with death. After assessing the presence of interaction and multicollinearity between variables, multivariable analysis, including multiple variables, was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Biomarkers or other variables with high correlation coefficients (> 0.5) were excluded from the multivariable analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two-tailed test). All analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Age distribution and outcome of patients with iSDSE infection

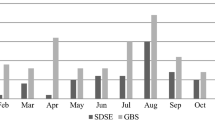

Three hundred nineteen cases (54.3%) were males and 269 cases (45.7%) were females. The median age of patients with iSDSE infections (n = 588) was 78 [interquartile range (IQR): 68─86] years. The mortality rate of patients under the age of 60 years ranged from 0.0 to 7.7%, whereas that of patients aged 60 years and older increased from 8.7 to 19.2% (see Fig. 1).

Clinical characteristics associated with outcome

The clinical characteristics associated with outcome are shown in Table 1. Regarding disease severity, 90.8% (n = 534) of all patients had mild-to-moderate disease, and the mortality rate was 4.3% (n = 23). The remaining 9.2% of patients (n = 54) identified as having severe disease had a significantly increased mortality rate of 70.4% (n = 38; p < 0.001). Of the 491 patients in whom the presence or absence of underlying diseases could be clarified, 97.4% (n = 478) had underlying diseases. However, there were no underlying diseases that showed a significant difference between the groups. Bacteraemia without primary focus and cellulitis were the most common manifestations, accounting for 36.9% (n = 217) and 35.2% (n = 207) of all patients, respectively. Significant differences associated with fatal outcome were obtained in patients with bacteraemia without primary focus, NF, meningitis, and STSS.

The categories of antimicrobial agents administered as initial treatment did not differ between the groups, except for carbapenems, which were mainly used in the mortality group (Supplementary Fig. 2). For macrolides and clindamycin agents, 18.9% of isolates possessed ermA, ermB, or mefA, and there were significantly more strains with resistance genes in the mortality group. There was no significant difference in mortality between stG6792, which was the most predominant emm type, and the other types.

Association of laboratory findings with outcome

Based on the cut-off value of each biomarker, the significant difference, hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) between the survival and mortality groups were calculated (Table 2). Patients with a WBC count < 4 × 103 cells/µL or a platelet (PLT) count < 10 × 104 cells/µL on admission showed a significant difference with high HRs in the mortality group. The C-Reactive protein level (CRP, ≥ 20 mg/dL) also significantly differed, but with low HRs. Abnormal levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST, ≥ 100 IU/L), blood urea nitrogen (BUN, ≥ 30 mg/dL), serum creatinine (Cr, ≥ 2.0 mg/dL), serum creatine kinase (CK, ≥ 300 IU/L), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, ≥ 300 IU/L) were higher in the mortality group than in the survival group (p < 0.001). The HRs of these biomarkers ranged from 1.8 for alanine aminotransferase (ALT) to 10.1 for WBC counts. The ROC curves of biomarkers are provided in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Disease severity and death in relation to the time elapsed after admission

Figure 2 shows the relationship between disease severity, which correlated the most with death (Table 1) and duration of hospital stay in the fatal cases. The mortality rate was 70.4% (n = 38) in patients with severe disease and 4.3% (n = 23) in patients with mild-to-moderate disease. The mortality rate within 2 days after admission was 48.1% in patients with severe disease and 1.3% in those with mild-to-moderate disease (Fig. 2a). Based on Kaplan–Meier analysis, we estimated the probability of survival to 28 days of hospitalisation (Fig. 2b). Patients with severe disease were significantly less likely to survive 28 days than those with mild-to-moderate disease (p < 0.001, log-rank test). The Kaplan–Meier curves indicated that death risk was the highest during the first 2 days after hospitalisation.

Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated a significant difference for the WBC count, PLT count, Cr level, and CK level between the survival and mortality groups in the univariate analysis, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. Abnormal levels of leukopenia (WBC < 4,000 cells/µL), thrombocytopenia (PLT < 10 × 104 cells/µL), and organ injury (Cr ≥ 2.0 mg/dL and CK ≥ 300 IU/L) were associated with decreased survival (p < 0.001, log-rank test). Additionally, cases of leukopenia were more likely to end fatally within 5 days.

Prognostic factors related to 28-day mortality

Risk factors associated with fatal outcomes in the multivariable analysis are shown in Table 3. The analysed characteristics were age, disease severity, clinical manifestations, biomarkers, and macrolide resistance. After excluding biomarkers that were identified as confounding factors, Cr and CK levels, which were presumed to be clinically meaningful based on the Kaplan–Meier analysis, were finally selected. Age ≥ 60 years, severe disease, bacteraemia without primary focus, other invasive infections, Cr ≥ 2.0 mg/dL, CK ≥ 300 IU/L, and macrolide resistance were significant independent risk factors for death in patients with iSDSE infections.

Antibiotic susceptibility

The MIC range, MIC50, and MIC90 of ten antimicrobial agents for SDSE strains are shown in Supplementary Table 1. With the exception of cefazolin, all β-lactam agents tested presented excellent susceptibility with MIC90s from 0.063 to 0.031 µg/mL. No mutations were identified in pbp1a, pbp2x, and pbp2b encoding the respective penicillin-binding proteins associated with β-lactam resistance (data not shown).

Association between emm type and patient prognosis

The proportion of the emm type in all isolates divided into survival and mortality groups is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. In stG10 and stG5420, the proportion of fatal cases was slightly higher, but there was no significant difference between the groups for all types, including stG6792, which is the most isolated in Japan.

Discussion

In this most extensive surveillance of adults with iSDSE infections in Japan, we revealed an overall 28-day mortality rate of 10.4%, which was significantly associated with older age (≥ 60 years), disease severity, clinical manifestations, biomarkers on admission, and macrolide resistance.

As expected, disease severity on admission was an independent risk factor significantly associated with mortality. Clinical evaluation of disease severity according to the guidelines is crucial for physicians to promptly predict iSDSE infection prognosis.

Here, the number of patients and mortality rate increased with age, and advancing age had a large effect on the mortality rate. Moreover, most patients with iSDSE infections had various underlying diseases. Inflammatory responses to SDSE infection may be impaired with aging, leading to fragility and increased susceptibility to recurrent or persistent infections. Chronic inflammation associated with aging, termed ‘inflammaging’, is a risk factor for diabetes mellitus, malignancy, cardiovascular disease, and kidney disease [23]. We hypothesise that these processes, including aging, SDSE colonisation, and underlying disease progression, contribute considerably to the morbidity and mortality of patients with SDSE infections in Japan, which is a super-aged society.

Bacteraemia without primary focus and other invasive infections (such as bacteraemic pneumonia, NF, meningitis, and STSS) had poor prognosis compared to cellulitis. The fatality rates were 18.0 and 12.4%, respectively, which are consistent with those reported in previous studies, with 13 to 20% [7,8,9, 14, 24].

Regarding the laboratory findings, WBC < 4,000 cells/µL, Cr ≥ 2.0 mg/dL, and CK ≥ 300 IU/L were important biomarkers and correlated strongly with poor outcomes. Studies describing biomarkers as predictors of mortality in patients with SDSE are limited. One previous study reported that patients with SDSE infections had an increased mortality rate with leukopenia (WBC < 5,000 cells/µL) and thrombocytopenia (PLT < 13.0 × 104 cells/µL) [13]. International guidelines [18, 20, 21] on severe conditions in patients with each disease particularly emphasise leukopenia (WBC < 4,000 cells/µL). Additionally, acute tubular necrosis resulting from sepsis-induced tissue hypotension and/or hypoxemia may contribute to renal injury, as shown by the laboratory findings such as Cr ≥ 2.0 mg/dL. Moreover, the serum concentrations of CK, which is released into the bloodstream when muscle cells disintegrate, increased in patients with poor outcomes. Thus, high CK concentrations may reflect extensive or systemic injury caused directly by SDSE infections or indirectly by hypoperfusion, indicating multiple organ damage rather than a specific diagnosis. Our study also revealed that patients infected by isolates harbouring the macrolide-resistance gene had a significantly poor prognosis. The mechanism and clinical relevance remain to be explored.

Regarding the emm type, stG6792 has constantly been the most prevalent in Japan [12, 25], and it is also emerging in other countries. In European countries, stG62647 has recently become more prevalent [13, 26, 27] in addition to stG643, stG485, stG6, and stC74a [10, 11, 28, 29]. According to the CDC database concerning the emm type, the stG6792 reference strain appears to be derived from India, suggesting that this type was transmitted from India to Japan. The routes of transmission and the reasons for variation in the dominant emm types among countries should be elucidated.

Our study has some limitations. First, although we evaluated mortality risk according to the clinical manifestations based on three groups (cellulitis, bacteraemia without primary focus, and others), the risk of death for each disease might have been underestimated. For example, NF and STSS, the most serious forms of iSDSE infections, were included in the ‘others’ category, which includes various invasive diseases. However, we elucidated a poor prognosis of bacteraemia without a primary focus compared to cellulitis. Second, the number of patients with STSS, which is associated with mortality, was small (n = 4) in this study, and the proportion of STSS from SDSE is lower than that from GAS. We conducted a six-year surveillance program for the three streptococcal species GAS, SDSE, and S. agalactiae (GBS) as part of the “Nationwide Invasive Streptococcal Disease Surveillance”. As a result, STSS cases in adults were 7.1% (23/326) for GAS and 0.7% (4/588) for SDSE, and 0.5% (2/443) for GBS. We included patients with invasive SDSE, which was defined as isolation of SDSE from normally sterile clinical samples such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and closed pus. However, according to the study protocol, we excluded patients with SDSE from a wound culture accompanied by necrotizing fasciitis or streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. In addition, the unique Japanese “universal health insurance system”, which provides good access to medical institutions and makes it easy to prescribe antibiotics could have had an impact on morbidity and mortality. Moreover, the differences in lifestyle habits between Japan and western countries may have influenced the results. Future surveillance will need to elucidate this issue through global collaboration. Third, we could not analyse missing data (lack of basic information or loss on follow-up), which accounted for 14.3% (n = 98) of the total cases based on our retrospective design. However, we confirmed that the demographics, clinical manifestations, and prognosis of those patients did not significantly differ from those included in this study. Fourth, we categorised disease severity into two groups, ‘mild-to-moderate’ and ‘severe’. As shown in Table 1, various diseases comprise iSDSE infections. For example, the practice guidelines for skin and soft tissue infection [18] define disease severity as “mild,” “moderate,” and “severe,” whereas those for other diseases [20, 21] categorise severity into “non-severe” and “severe.” Therefore, we divided patients with iSDSE infections into “mild-to-moderate” and “severe” groups. Finally, the proportion of antibiotic classes as the initial therapy differed between the survival and mortality groups because the empiric antibiotic treatment was influenced by apparent disease severity. Furthermore, combination therapy of penicillin with clindamycin for life-threatening infections was given to a small number of patients, and its efficacy remains unclear.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence of prognostic factors for death due to iSDSE infections and the basis for evaluating clinical manifestations, disease severity, and biomarkers on admission. The prevalence and burden of iSDSE infection, which particularly affects older adults with underlying diseases, are likely to further increase in developed countries. Strategies to reduce the mortality risk of iSDSE infections require further investigations of dynamic molecular epidemiology and clinical characteristics, as well as optimal treatment based on well-conducted studies.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Vandamme P, Pot B, Falsen E, Kersters K, Devriese LA (1996) Taxonomic study of Lancefield streptococcal groups C, G, and L (Streptococcus dysgalactiae) and proposal of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis subsp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 46:774–781. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-3-774

Brandt CM, Haase G, Schnitzler N, Zbinden R, Lütticken R (1999) Characterization of blood culture isolates of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis possessing Lancefield’s group A antigen. J Clin Microbiol 37:4194–4197. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.37.12.4194-4197.1999

Shimomura Y, Okumura K, Murayama SY, Yagi J, Ubukata K et al (2011) Complete genome sequencing and analysis of a Lancefield group G Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strain causing streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (STSS). BMC Genom 12:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-12-17

Watanabe S, Kirikae T, Miyoshi-Akiyama T (2013) Complete genome sequence of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis 167 carrying Lancefield group C antigen and comparative genomics of S. dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis strains. Genome Biol Evol 5:1644–1651. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evt117

Facklam R (2002) What happened to the Streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:613–630. https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.15.4.613-630.2002

Humar D, Datta V, Bast DJ, Beall B, De Azavedo JC et al (2002) Streptolysin S and necrotising infections produced by group G streptococcus. Lancet 359:124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07371-3

Ekelund K, Skinhøj P, Madsen J, Konradsen HB (2005) Invasive group A, B, C and G streptococcal infections in Denmark 1999–2002: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Infect 11:569–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01169.x

Broyles LN, Van Beneden C, Beall B, Facklam R, Shewmaker PL et al (2009) Population-based study of invasive disease due to β-hemolytic streptococci of groups other than a and B. Clin Infect Dis 48:706–712. https://doi.org/10.1086/597035

Rantala S, Vuopio-Varkila J, Vuento R, Huhtala H, Syrjänen J (2009) Predictors of mortality in beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteremia: a population-based study. J Infect 58:266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.**f.2009.01.015

Kittang BR, Bruun T, Langeland N, Mylvaganam H, Glambek M et al (2011) Invasive group A, C and G streptococcal disease in western Norway: virulence gene profiles, clinical features and outcomes. Clin Microbiol Infect 17:358–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03253.x

Loubinoux J, Plainvert C, Collobert G, Touak G, Bouvet A et al (2013) Adult invasive and noninvasive infections due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis in France from 2006 to 2010. J Clin Microbiol 51:2724–2727. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01262-13

Takahashi T, Sunaoshi K, Sunakawa K, Fujishima S, Watanabe H et al (2010) Clinical aspects of invasive infections with Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis in Japan: differences with respect to Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus agalactiae infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:1097–1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03047.x

Oppegaard O, Glambek M, Skutlaberg DH, Skrede S, Sivertsen A (2023) Streptococcus dysgalactiae bloodstream infections, Norway, 1999–2021. Emerg Infect Dis 29:260–267. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2902.221218

Rantala S (2014) Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis bacteremia: an emerging infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:1303–1310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2092-0

Nevanlinna V, Huttunen R, Aittoniemi J, Luukkaala T, Rantala S (2023) Major risk factors for Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis bacteremia: a population-based study. BMC Infect Dis 23:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-07992-9

Bruun T, Kittang BR, de Hoog BJ, Aardal S, Flaatten HK et al (2013) Necrotizing soft tissue infections caused by Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis of groups C and G in western Norway. Clin Microbiol Infect 19:E545–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12276

Bruun T, Rath E, Madsen MB, Oppegaard O, Nekludov M et al (2021) Risk factors and predictors of mortality in streptococcal necrotizing soft-tissue infections: a multicenter prospective study. Clin Infect Dis 72:293–300. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa027

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJC et al (2014) Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 59:e10–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu444

Mayumi T, Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS et al (2018) Tokyo guidelines 2018: management bundles for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 25:96–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.519

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J et al (2019) Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200:e45–67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM et al (2021) Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med 47:1181–1247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y

Sunaoshi K, Murayama SY, Adachi K, Yagoshi M, Okuzumi K et al (2010) Molecular emm genoty** and antibiotic susceptibility of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis isolated from invasive and non-invasive infections. J Med Microbiol 59:82–88. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.013201-0

Ferrucci L, Fabbri E (2018) Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol 15:505–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-018-0064-2

Lother SA, Demczuk W, Martin I, Mulvey M, Dufault B et al (2017) Clonal clusters and virulence factors of group C and G streptococcus causing severe infections, Manitoba, Canada, 2012–2014. Emerg Infect Dis 23:1079–1088. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2307.161259

Wajima T, Morozumi M, Hanada S, Sunaoshi K, Chiba N et al (2016) Molecular characterization of invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis 22:247–254. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2202.141732

Bläckberg A, Nilson B, Özenci V, Olaison L, Rasmussen M (2018) Infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus dysgalactiae: clinical presentation and microbiological features. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 37:2261–2272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-018-3367-7

Itzek A, Weißbach V, Meintrup D, Rieß B, van der Linden M (2023) Epidemiological and clinical features of Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis stG62647 and other emm types in Germany. Pathogens 12(589). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12040589

Oppegaard O, Mylvaganam H, Kittang BR (2015) Beta-haemolytic group A, C and G streptococcal infections in Western Norway: a 15-year retrospective survey. Clin Microbiol Infect 21:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2014.08.019

Lambertsen LM, Ingels H, Schønheyder HC, Hoffmann S et al (2014) Nationwide laboratory-based surveillance of invasive β-haemolytic streptococci in Denmark from 2005 to 2011. Clin Microbiol Infect 20:O216–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-0691.12378

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the laboratory staff and physicians who participated in the surveillance activity; Madoka Naito and Shinji Masuyoshi for their laboratory support; Shigeaki Ohtsuki, PhD, a representative of the Japan Institute of Statistical Technology, for providing research support in the statistical analysis; and Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

Our study was partially funded by a grant under the category ‘‘Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases’’ (H22-013) from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (to K. Ubukata).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. and K.U. are the chief investigators responsible for organising the study. T.W., M.T., M.M., M.S., and S.I. were responsible for the coordination of this study, including the genoty** of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis, and data analysis and manuscript drafting. All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and Guidelines for Epidemiologic Studies issued by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Keio University School of Medicine Ethics Committee (approval number: 20130455); the requirement for obtaining written informed consent from patients was waived owing to the use of anonymised stored samples and data. Patient medical records in a database were obtained anonymously using a survey form completed by attending physicians.

Competing interests

The following authors received financial support within the last 3 years: S. I. from Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Pfizer Japan Inc., Astellas Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., and Gilead Sciences. Inc.; K.U. from Pfizer Japan Inc., HORIBA, Ltd., and Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanada, S., Wajima, T., Takata, M. et al. Clinical manifestations and biomarkers to predict mortality risk in adults with invasive Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-024-04861-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-024-04861-4