Abstract

To explore the needs, expectations, and experiences of asylum-seeking parents and unaccompanied minors under the age of 18 years on the initial health assessment for children and adolescents and access to care upon entry in the Netherlands, We conducted five semi-structured focus group discussions with asylum-seeking parents and unaccompanied minors, from Syria, Eritrea, Afghanistan, and other Middle-East and African countries, supported by professional interpreters. To triangulate findings, semi-structured interviews with health care professionals involved in care for refugee children were conducted. Transcripts of focus group discussions were inductively and deductively coded and content analyzed; transcripts of interviews were deductively coded and content analyzed. In total, 31 asylum-seeking participants: 23 parents of 101 children (between 0 and 18 years old), 8 unaccompanied minors (between 15 and 17 years), and 6 healthcare professionals participated. Parents and minors expressed that upon entry, their needs were met for vaccinations, but not for screening or care for physical and mental health problems. Parents, minors, and health professionals emphasized the necessity of appropriate information and education about health, diseases, and the health system. Cultural change was mentioned as stressful for the parent–child interaction and parental well-being.

Conclusion: The perspectives of refugee parents and unaccompanied minors revealed opportunities to improve the experience of and access to health care of refugees entering the Netherlands, especially risk-specific screening and more adequate education about health, diseases, and the Dutch health care system.

What is Known: • Refugees have specific health needs due to pre-flight, flight, and resettlement conditions. Health assessment upon entry was non-obligatory in the Netherlands, except for the tuberculosis screening. Health needs were not always met, and refugees experienced barriers in access to care. | |

What is New: • The initial health assessment met the needs concerning vaccinations but mismatched the needs regarding physical and mental health assessment. Screening for specific risk-related diseases and mental health could enable refugee parents and minors to engage better with the health system. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The number of people forcibly displaced from their homes increased considerably over the past years worldwide. Among the nearly 90 million of them, about 27 million were refugees in 2021. Minors under the age of 18 years, making up about a third of the world population, constitute about half of the refugee population [1]. In 2021, over 120,000 refugees arrived in Europe, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Netherlands, the majority of refugees enter through an asylum procedure or family reunification afterward; new asylum requests from 2015 to 2021 counted 237,000 applications, of whom nearly 42,000 children under the age of 18 (Appendix I [2, 3]).

More than 12,000 came unaccompanied by a parent. Asylum-seekers from Syria were the largest group, followed by people from Eritrea. Other important countries of origin were Nigeria, Iran, Iraq, and Afghanistan [4].

Refugees often have complex health care needs, ranging from infectious and chronic diseases to mental problems or disorders [5,6,7]. Refugee children have an increased risk for a variety of conditions compared to children born in the Netherlands, including anemia, genetic disorders of the red blood cells, infectious diseases, growth and nutrition disorders, incomplete vaccination status, and psychosocial problems [8]. Unfavorable conditions in their home countries, the flight and migration itself, the stress of living in unfamiliar surroundings, and the uncertainty about their asylum-seeking status all contribute to increased risks and vulnerability of mental and physical health problems [9,10,11].

In the Netherlands, Youth Health Care monitors the health status of all children, through antenatal and neonatal screening and follow-up during childhood and adolescence. Youth Health Care also conducts the initial health assessment of asylum-seeking children and adolescents arriving in the Netherlands, taking place during their stay in reception centers. This initial health assessment is non-mandatory and consists of an intake with anamnesis, a physical examination of growth and development, and an evaluation of the health status and well-being of the children [12]. An inventory of the vaccination status is made, and necessary additional vaccinations are provided [13]. Screening for tuberculosis is provided upon entry, for detecting pulmonary tuberculosis in people from high prevalence countries. When required, children are referred to specialist care services. This initial health assessment does not include laboratory tests or standardized mental health screening.

The initial health assessment is crucial for access to care because it focuses on the early detection of health problems and needs and initiates referrals to health care services. Levesque et al. defines access to health care as “the opportunity to have health care needs fulfilled” [14]. Perspectives of asylum-seekers on their health, the assessment, and the care provided in their reception country are of key importance to understand access and match their needs. However, their perspectives have scarcely been studied. The first European study investigating the perspective of asylum-seeking and refugee caregivers was about the quality of care provided in a pediatric tertiary hospital. It described a mismatch of personal competencies and external challenges such as communication barriers and unfamiliarity with new health concepts [15]. Other studies about parental perspectives identified important barriers for accessing health care and unmet health needs [16].

The aim of the current study was to better understand how asylum-seeking parents of children and unaccompanied minors experience the initial health assessment and access to care after arriving in the Netherlands.

Methods

Design, context, and ethics

We designed a qualitative study with focus group discussions (FGD) and semi-structured interviews. Focus groups consisted of asylum-seeking parents and unaccompanied minors with rejected asylum requests. Interviews were conducted with health care professionals working in reception centers and with other refugees than our study population. From 50 reception centers in the Netherlands in 2018, we approached one center in Arnhem in which many families reside, hosting on average about 400 people, among which are 100 children. The inhabitants were asylum-seekers waiting for their asylum decision and refugees with a residence status, waiting for a regular house or apartment. Focus group discussions (FGD) with parents of children were held in this center. A nearby small-scale housing facility in Arnhem for unaccompanied minors (UMs) with rejected asylum request was approached to recruit minors. The personnel of the reception center were informed in a training about the study, the independency of the researchers, and the informed consent procedure to ensure voluntary participation in the recruitment, transparency, and confidentiality.

Recruitment and informed consent

Parents and UMs were recruited in collaboration with employees from the National Central Organ of Asylum-seekers (COA), working in the Arnhem Center or minor housing facility. The employees orally invited parents and UMs through purposive sampling to voluntarily participate in a group discussion about health assessment and access. They distributed a study flyer in five languages to ensure representation from the main regions of origin. Researchers provided written and oral information about the study to the managers of the locations to the UM guardians who had custody and to the participants themselves for recruitment. At the start of each FGD, we gave the informed consent forms in the specific language at hand to the participants and discussed—via an interpreter—information and consent with them. Researchers answered questions of participants, and, after that, participants gave written consent. UMs’ guardians were asked permission to conduct a FGD with minors; they gave written consent after oral assent by the minors. Health professionals were recruited with the snowball technique, starting with professionals in the network of the first authors.

In the report of this study, we followed the COREQ guidelines [17].

Data collection, language, and interpretation

At each FGD, a professional interpreter, recruited through a licensed bureau for interpreters, was present to translate between Dutch and the mother tongue of the participants (two FGDs in Arabic, one Farsi, one Dari, and one Tigrinya). The interpreters were briefed before to explain the aim of the FGD and the most important concepts. The questions were asked in Dutch and translated in the language of the participants, and the answers were translated back into Dutch. The transcripts were analyzed and coded in English.

Analysis

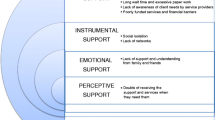

The audio-recorded FGDs and interviews were transcribed using verbatim style. The transcripts were coded with ATLAS.ti 7 software (ATLAS.ti GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A combination of a deductive and inductive approach was used in the analysis. Each transcript was read several times in order to gain familiarity with the data. A deductive approach was used for all fragments concerning access to health care by health care professionals based on the five access dimensions (approachability, acceptability, availability, affordability, and appropriateness) and their corresponding patient abilities (ability to perceive, to seek, to reach, to pay, and to engage) by Levesque [14] (see Fig. 1). Next, open coding was used, and the subsequent codes resulted in a coding scheme. Then, axial coding was used for all fragments concerning experiences and needs of the study group on the initial health assessment. Data analysis was a circular process of going back and forth adding new codes or labels where necessary [18]. Final themes were created based on the prevalence of certain codes and their interrelation, or the salience of a theme in relation to the research questions. Appendix II contains the final coding scheme. Two researchers (CB, SFA) coded the transcriptions. Two others (AB, MH) double-coded a selection of the transcripts. Differences were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Note: A conceptual framework of access to health care (Levesque et al. [14]). Reprinted from “Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations” by J-F. Levesque, M.F. Harris, and G. Russell, 2013, International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), p. 5.]

Results

A total of 31 participants were involved in the FGDs; 23 parents (12 mothers, 11 fathers) of one to twelve children per parent—but not all children lived in the center or in the Netherlands and 8 unaccompanied minors with a negative asylum decision (male, aged 15 to 17 years). The parents were either in the asylum process or were recently granted residency in the Netherlands but still living in the center waiting for accommodation elsewhere. Participants came from nine countries, mostly from Syria, Eritrea, or Afghanistan (Table 1).

Focus group sizes varied between five and eight participants.

Six health care professionals were interviewed (5 female; 4 face-to-face, and 2 by telephone): three doctors (GP, Pediatrician, Youth Health physician), one nurse, one manager, and one policy advisor. The doctors and nurse had daily or weekly consultations with refugees, the two other professionals worked exclusively in health care for refugees (Table 2).

Initial health assessment

In general, parents and unaccompanied minors did not understand that they had received an initial health assessment, with the exception of being asked about and possibly receiving vaccinations. Vaccinations were well received, both by parents and adolescents. Some minors confessed they were reluctant to go for future vaccinations or what they called check-ups, for example, because they were afraid of injections or perceived they did not need them (“I feel healthy”). Some were unable to find the location or felt barriers to see a doctor (Table 3, quote 7). (See Appendix IV for all characteristics of the participants).

Parents expressed worries about the health and nutritional status of their children because children suffered during the war, during the flight, and in the Netherlands (Table 3, quote 1–2). Some children had spent time in prison. Parents, especially mothers, and minors expressed needs and expectations regarding physical and mental health screening (Table 3, quote 8) and a more extensive initial health assessment or follow-up. Mothers expressed a wish to learn more about health, diseases, and prevention (Table 3, quote 4).

Parents from countries where thalassemia screening was obligatory before marriage, due to the high prevalence in the general population (Syria, Turkey), expected such screening in the Netherlands as well (Table 3, quote 3). UMs stated they would prefer a screening upon entry instead of going to a doctor on their own initiative (Table 3, quote 7).

Psychosocial issues were mentioned in every FGD. Parents told about nightmares, bedwetting, and anxiety of their children (Table 4), who had recurrent thoughts of the war.

They mentioned specific needs as refugees who fled from a war zone (Table 3, quote 8) and suffered severe psychological consequences (Table 3, quote 9). Children taken out of their beds at night by the police in the Netherlands suffered from severe post-traumatic stress symptoms. The parents and minors who traveled through Libya were especially worried about mental and trauma health issues. They were not able to talk about their experiences because it was too stressful (Table 3, quote 7).

Uncertainty about their residence status was a big stressor for the unaccompanied minors and influenced the ability to perceive health needs and act accordingly. Continuity of care for extensive mental health and psychosocial problems was discussed in all focus groups. Minors identified that they had major mental health problems, but they did not search for care nor were referred care or support. In all FGDs, unmet needs regarding mental health and social problems were mentioned.

Access to health care

Differences between the health care system in the Netherlands and the country of origin were discussed (Table 5).

None of the participants could explain the organization of the Dutch health care for asylum-seekers, nor understood the distinction between preventive Youth Health Care, primary care by a general physician, and secondary curative services. The need for information and education on health and diseases was discussed extensively, among refugees and among healthcare professionals. Various ideas and suggestions were brought up regarding factors that may influence the ability of refugees to obtain information, such as access to the internet, recall of diagnosis or care used in the country of origin, and social contacts in the neighborhood.

Participants perceived that treatment or care for refugees was postponed and delayed, and they expressed their concern about long waiting times and the complex Dutch referral system. Parents of children with complex health needs were often not informed in their own language about the condition of their child, or only with the help of an informal “interpreter,” for example, a relative with little understanding of the Dutch or English language.

Parents and minors had to get used to the reluctance of health care providers to subscribe antibiotics in the Netherlands, in comparison to receiving antibiotics over the counter in their country of origin.

The health professionals’ experiences with access to care for asylum-seeking parents and UMs, were related to the five access dimensions of Levesque (Table 6).

The doctor-patient relationship was a recurrent topic, as it takes time to build such a relationship, especially in an intercultural setting. Professionals acknowledged that it took time to build trust and gain authority with the refugee population. Health care professionals underlined the importance of professional interpreters.

Parenting in between cultures

Although not asked for explicitly, cultural change was mentioned spontaneously as part of parental and children’s well-being. Parents told they tried to maintain their own cultural values and practices, while their children quickly accommodated Dutch cultural practices at school. Parents perceived that this cultural gap led to uncertainty about norms and values, to parent–child conflicts (Table 3, quote 10 and 11), or to professionals not taking into account or respecting parental norms and values (Table 3, quote 12). Parents experienced difficulties in raising their children without their extended family and compatriots around.

Parents stated that their children had little social contact with other children. Relocations from center to center negatively influenced the establishment of a social network. Parents expressed their need for parental support (Table 3, quotes 10–12).

Discussion

We explored the experiences of asylum-seeking parents and unaccompanied minors toward the initial health assessment of children upon entry and their perceptions toward access to health care in the Netherlands.

Parents and minors were not always aware of the scope and possibilities of the initial health assessment nor recalled to have had such an assessment. They were satisfied with the vaccination program but missed screening for specific diseases and for psychosocial problems. They expressed the need for an extended initial health assessment about the health and nutritional status of their children or themselves as minors, especially those who had been in a war zone for a long time or traveled through Libya. Their needs for trauma detection, support, or care were not met, and parents and minors expressed their wish for trauma support. Parents mentioned the importance of support for dealing with cultural transitions while raising their children. They experienced multiple barriers in access to care, which were corroborated by health professionals.

Parents and minors in our study were often unfamiliar with the initial health assessment, which is in line with a Swedish study, in which new migrants did not understand the rationale for screening, as they may have symptom-driven health-seeking behaviors [19]. In our study, lack of information on the health care system of the new country may have acted as a barrier in perceiving one’s own health needs and engaging in this system.

Our study participants experienced a mismatch between their health needs and expectations versus the initial health assessment. However, a more extensive health assessment does not necessarily lead to higher satisfaction because asylum-seekers may fear lack of confidentiality of the test results, which might influence the asylum procedure [19].

Parents realized they did not have access to standard screening for thalassemia in the Netherlands, a test obligatory before getting married in home countries with a high prevalence of thalassemia and other genetic blood disorders [20, 21]. Parents observed a gap between the neonatal screening in the Netherlands and the premarital screening in their home countries. As screening is not available to them in the Netherlands, this hindered their ability to reach health services and take part in the system.

Parents and minors who traveled through Libya were worried about possible acquired sexually transmittable diseases. In terms of Levesque, we interpreted this as trauma influencing their ability to perceive and recognize health needs which, in turn, hindered them to engage in the health care system (see Fig. 1).

The Central Mediterranean Route, passing through Libya, is one of the most dangerous routes for migrants [22]. The prevalence of (sexual) violence is high. Many women reported a pregnancy during travel [22, 23]. UNICEF rose alarm in 2020 about the high risk of UMs amidst violence and chaos of the unrelenting conflict [24]. In our study, the minors did not want to reveal what exactly happened in Libya. The Tigrinya interpreter told us in person after the FGD that the minors probably indirectly meant sexual abuse. Sexual abuse increases health risks, and the initial health assessment could be an instrument linking them to care.

Trauma was a salient topic in the FGDs. Parents reported symptoms of PTSS among their children. For the minors, the main stressor was the asylum procedure itself, leaving them in despair after a negative asylum request. The stress of uncertainty, lack of perspective, and social support with frequent relocations hindered them to engage in the health care system. A recent review concluded that forced migration and a prolonged asylum procedure, in addition to the complexity of the acculturation process, can contribute to higher levels of psychopathology [25].

Stress, war trauma, post-traumatic stress, and mental health problems were major barriers in participants’ ability to perceive health needs, to seek the right (preventive) services, and to engage in the health care system. As conceptualized by Levesque, refugee parents’ and minors’ limited or unfacilitated abilities to perceive, seek, reach, and engage (in) health care, all played a role in the access.

We recommend an improved initial health assessment that recognizes and addresses the health needs of asylum-seeking children, both physical and mental. With regard to physical health, this should include standardized screening for most common problems according to region of origin. Regarding mental health, we recommend a standardized screening with validated and cultural sensitive screening instruments. Such an initial health assessment might detect health needs better and may lead to more adequate referral. Furthermore, an adaptive and reciprocal approach of health providers is essential for enhancing the engagement of asylum-seeking children with the health care system, leading to improved health outcomes for this vulnerable population.

Strengths and limitations of the study

A strength of this study is the inclusion of perspectives of three different stakeholder groups on the initial health assessment and access to health care as triangulation: asylum-seekers, parents and minors from various regions of origin, and health care professionals.

A limitation of the study was the language barrier, which limited communication between researchers and refugees. Even though professional interpreters were present, they may have adjusted the interview questions and refugees’ responses. Another limitation is that refugees are in a vulnerable position, and fear of the outcome of the asylum procedure may have influenced their responses. Another limitation is the possibility of selection bias because recruitment was done in the reception centers, and we did not have insight in motivation to participate or not. We only interviewed male UMs with a rejected asylum request; their responses might have been biased because they may be less motivated to seek healthcare even when having complaints than UMs still in asylum procedure or with a residence permit. We only recruited parents and UMs from one reception center, which may have biased our results [26].

Conclusion

The perspectives of refugee families and unaccompanied minors revealed opportunities to improve the experience of and access to health care of refugees entering the Netherlands.

Specifically a risk-specific screening and mental health assessment. Health literacy and adequate education about health, diseases, and the health system would help them engage to the system and more adequately address their health needs. Improving the initial health assessment could enable asylum-seeking parents and minors to better recognize their health needs, reach the right services, engage in the health care system, and find appropriate services.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets in the form of transcripts, without information that might be traceable to persons, can be accessed by direct contact with the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- FGDs:

-

Focus group discussions

- UMs:

-

Unaccompanied minor asylum-seekers

References

UNHCR/WFP. Global trends forced displacement in 2019 2022 [cited 2022 2022–5–21]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/data.html

IND. Asylum trends December 2017 t/m 2021 Available from: https://ind.nl/nl/documenten/03-2022/atdecember2021hoofdrapport.pdf

Baauw A, Rosiek S, Slattery B, Chinapaw M, van Hensbroek MB, van Goudoever JB, Kist-van HJ (2018) Pediatrician-experienced barriers in the medical care for refugee children in the Netherlands. Eur J Pediatr 177(7):995–1002

Statistiek CBv. Dossier Asiel, migratie en integratie 2019: cbs; 2022 Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/dossier/dosier-asiel-migratie-en-integratie

Yun K, Matheson J, Payton C, Scott KC, Stone BL, Song L et al (2015) Health profiles of newly arrived refugee children in the United States, 2006–2012. Am J Public Health 106(1):128–135

Hunter P (2016) The refugee crisis challenges national health care systems: countries accepting large numbers of refugees are struggling to meet their health care needs, which range from infectious to chronic diseases to mental illnesses. EMBO Rep 17(4):492–495

Harkensee C, Andrew R (2021) Health needs of accompanied refugee and asylum seeking children in a UK specialist clinic. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992)

Baauw A, Kist-van Holthe J, Slattery B, Heymans M, Chinapaw M, van Goudoever H (2019) Health needs of refugee children identified on arrival in reception countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open 3(1):e000516

Goosen S, Hoebe CJPA, Waldhober Q, Kunst AE (2015) High HIV prevalence among asylum seekers who gave birth in the Netherlands: a nationwide study based on antenatal HIV tests. PLoS ONE 10(8):e0134724

Hebebrand J, Anagnostopoulos D, Eliez S, Linse H, Pejovic-Milovancevic M, Klasen H (2016) A first assessment of the needs of young refugees arriving in Europe: what mental health professionals need to know. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 25(1):1–6

Marquardt L, Kramer A, Fischer F, Prufer-Kramer L (2016) Health status and disease burden of unaccompanied asylum-seeking adolescents in Bielefeld, Germany: cross-sectional pilot study. Trop Med Int Health 21(2):210–218

GGDGHOR. Publieke Gezondheidszorg Asielzoekers (PGA): GGD-GHOR; 2022 Available from: https://ggdghor.nl/thema/publieke-gezondheid-asielzoekers

Vermeulen G, Slinger K, Zonnenberg I, Drijfhout I, Appels R (2017) Asielzoekerskinderen en het Rijksvaccinatieprogramma (RVP). JGZ Tijdschrift voor jeugdgezondheidszorg 49(1):14–17

Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G (2013) Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 12:18

Brandenberger J, Sontag K, Duchene-Lacroix C, Jaeger FN, Peterhans B, Ritz N (2019) Perspective of asylum-seeking caregivers on the quality of care provided by a Swiss paediatric hospital: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 9(9):e029385

Dawson-Hahn E, Koceja L, Stein E, Farmer B, Grow HM, Saelens BE et al (2020) Perspectives of caregivers on the effects of migration on the nutrition, health and physical activity of their young children: a qualitative study with immigrant and refugee families. J Immigr Minor Health 22(2):274–281

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Nkulu Kalengayi FK, Hurtig AK, Nordstrand A et al (2015) Perspectives and experiences of new migrants on health screening in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res 16:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1218-0

Kadhim KA, Baldawi KH, Lami FH (2017) Prevalence, incidence, trend, and complications of thalassemia in Iraq. Hemoglobin 41(3):164–168

Vichinsky E, Hurst D, Earles A, Kleman K, Lubin B (1988) Newborn screening for sickle cell disease: effect on mortality. Pediatrics 81(6):749–755

Reques L, Aranda-Fernandez E, Rolland C, Grippon A, Fallet N, Reboul C et al (2020) Episodes of violence suffered by migrants transiting through Libya: a cross-sectional study in “Medecins du Monde’s” reception and healthcare centre in Seine-Saint-Denis. France Confl Health 14:12

Argent E, Emder P, Monagle P, Mowat D, Petterson T, Russell S et al (2012) Australian paediatric surveillance unit study of haemoglobinopathies in australian children. J Paediatr Child Health 48(4):356–360

Fore H. Tens of thousands of children at risk amidst violence and chaos of unrelenting conflict: Unicef; 2020 Available from: https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/libya-tens-thousands-children-risk-amidst-violence-and-chaos-unrelenting-conflict

Pluck F, Ettema R, Vermetten E (2022) Threats and interventions on wellbeing in asylum seekers in the Netherlands: a sco** review. Front Psychiatry 13:829522

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 13(2):201–216

Acknowledgements

Staff of the asylum-seeker centers are acknowledged for their tremendous efforts to realize this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Albertine Baauw and Dr. Mariëtte Hoogsteder conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, reviewed initial data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Chanine Brouwers and Sogol Fathi Afshar conducted the FDGs with Albertine Baauw, co-designed the data collection instruments collected data, conducted the interviews, transcribed and coded the data, carried out the initial analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Prof. Mai Chin A. Paw, PhD and Prof. Hans van Goudoever, MD, PhD provided input in the study design, critically reviewed the manuscript, provided suggestions, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of Rijnstate Hospital (Central Commission on Human bound Research of Arnhem-Nijmegen IRB 091; May 2018). Participants were informed in their mother tongue about the study and each participant signed an informed consent form (in English, Arabic, Dari, Farsi, and Tigrinya). In case of illiteracy, an oral informed consent was given. All other regulations were followed during this study, including participation on a voluntary basis, confidentiality, not including COA staff, and withdrawal from the study at any time. We offered assistance by two independent pediatricians from the hospital in case of help needed, as safeguard after the group discussions. The study was carried out in line with the COREQ (17) standards.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Article Summary

The ability of refugee parents and minors to engage with health care is influenced by their perceived health needs and health care access.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baauw, A., Brouwers, C.F.S., Afshar, S.F. et al. Perspectives of refugee parents and unaccompanied minors on initial health assessment and access to care. Eur J Pediatr 183, 2871–2880 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05523-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-024-05523-5