Abstract

Background

Inadequate trauma care training opportunities exist in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Jos University Teaching Hospital and the West African College of Surgeons (WACS) have synergized, over the past 15 years, to introduce a yearly, certified, multidisciplinary Trauma Management Course. We explore the history and evolution of this course.

Methods

A desk review of course secretariat documents, registration records, schedules, pre- and post-course test records, post-course surveys, and account books complemented by organizer interviews was carried out to elaborate the evolution of the Trauma Management Course.

Results

The course was started as a local Continuing Medical Education program in 2005 in response to recurring cycles of violence and numerous mass casualty situations. Collaborations with WACS followed, with inclusion of the course in the College’s yearly calendar from 2010. Multidisciplinary faculty teach participants the concepts of trauma care through didactic lectures, group sessions, and hands-on simulation within a one-week period. From inception, there has been a 100% growth in lecture content (from 15 to 30 lectures) and in multidisciplinary attendance (from 23 to 133 attendees). Trainees showed statistically significant knowledge gain yearly, with a mean difference ranging from 10.1 to 16.1% over the past 5 years. Future collaborations seek to expand the course and position it as a catalyst for regional emergency medical services and trauma registries.

Conclusions

Multidisciplinary trauma management training is important for expanding holistic trauma capacity within the West African sub-region. The course serves as an example for Low- and Middle-Income contexts. Similar contextualized programs should be considered to strengthen trauma workforce development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over 5 billion people worldwide lack access to safe, affordable, and timely surgical care for a variety of reasons, and within this equity gap, trauma care is a huge chasm [1]. Trauma is a neglected pandemic responsible for at least 4.3 million deaths worldwide in 2019 alone—more deaths than malaria, tuberculosis, and AIDS combined [2]. This neglect is true both on an international and on a local scale as evidenced by lack of functional trauma systems in several Low- and Middle-income countries (LMICs), inadequate trauma care training opportunities, and significantly less funding for trauma care [1, 3,4,5,6,7]. The Jos University Teaching Hospital (JUTH) and the West African College of Surgeons (WACS) have synergised, over the past 16 years, to help address the challenge of trauma by the introduction of a certified, yearly, multidisciplinary Trauma Management Course.

Jos is the cosmopolitan capital of Plateau State, Nigeria, and represents a melting pot of cultures, languages, religious and political interests. The State houses a population of about 3.5 million from over 40 indigenous ethno-linguistic groups [8]. Sociocultural differences, terrorist activities and farmer-herdsmen clashes over land ownership have historically led to repeated civilian conflicts [9,10,11,12,13].

Over the years, JUTH has developed increasing capacity for trauma care with the development of the earliest documented Nigerian mass casualty response plan in 1997, the inauguration of a dedicated Trauma Division, establishing city-wide inter-facility collaboration, and the commencement of a detailed trauma registry in 2012 [14, 15]. The hospital is well positioned as a regional trauma centre and receives trauma patients from Bauchi, Taraba, Benue, Nasarawa, Kogi, Kaduna, Gombe states and the Federal Capital Territory. The hospital is a 620-bed facility with a regular trauma admissions capacity of 200 beds and a trauma surge capacity of about 400 beds [16].

The WACS is a leading regional surgical training institution [17]. With over 8,000 surgeons and numerous surgical trainees covering a geographical spread of 18 countries (Fig. 1), interventions scaled through the college have a great potential for impact [17].

The aim of this review is to document the origins, structure, impact, and value of a multidisciplinary WACS trauma management course in sub-Saharan Africa, and to share experience and lessons learned in 16 years of trauma education with other LMIC settings.

Materials and methods

For this review, we explored available course records of the past 16 years using narrative synthesis. We conducted a desk review of course secretariat documents, registration records, course schedules, account books, duplicate invitation letters and previous internal audits. Other information was gathered through verbal interviews with course pioneers and long-standing members of the Local Organising Committee (LOC). Yearly pre- and post-course test records were collated, and the trend of knowledge gain was assessed using paired sample t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for normally distributed and non-normally distributed scores, respectively. Post-course surveys over the years were reviewed for multidisciplinary participation and attendance trends.

Results

Origins of the course

The Trauma Management Course originated in direct response to recurring cycles of violence in Plateau State, which resulted in numerous mass casualty situations [10, 12, 15, 18]. As the crises evolved, more and more medical personnel without previous training in trauma care were participating in the care of these trauma patients. Concerned surgeons at JUTH observed the emerging trends in civilian trauma, and the pre-hospital and in-hospital challenges of managing these patients and moved for the start of a trauma course in 2004 as internal continuing medical education [10, 19]. Emphasis was on the management of the severely injured patient by practitioners who do not regularly manage trauma patients. The teaching hospital adopted the course in its second year, and the WACS reviewed and adopted the course into her calendar in 2010. The course takes place yearly, in the first week of December.

Course aim and objectives

The aim of the course is to inculcate the concepts of initial trauma care in those who care for the critically injured patient in a contextualised, West African setting. Participation is not only intended to develop human capacity, but also to inspire the development of trauma systems on broad national scales that will reduce death and disability following injury.

Course content

The course content focuses broadly on pre-hospital, emergency room, and in-hospital care of the trauma patient. Forty per cent of the course is dedicated to gaining practical skills including basic life support skills, pre-hospital trauma life support skills, Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma, fracture splinting and immobilization, application of fracture casts, diagnostic peritoneal lavage, thoracostomy, tracheostomy, wound management, application of cervical collars and lumbar corsets, and venous access among others (Table 1). Didactics focused on pre-hospital care, development of trauma systems, development of trauma registries, mass casualty management, disaster management, metabolic response to trauma, management of the polytrauma patient, trauma care anaesthesia, intensive care of the critical trauma patient, blood transfusion in trauma, and interpretation of radiological imaging for trauma patients. Forensic and legal considerations in trauma, in addition to trauma and mental health were also covered. The course also specifically covered management of bomb blast injuries, shock, traumatic wounds, head injuries, chest trauma, abdominal trauma, burns, spinal cord injuries, obstetrics and gynaecological trauma, urologic trauma, ophthalmic trauma, fractures and dislocations, maxillofacial ear, nose, throat and dental injuries, vascular injuries, and childhood trauma. Both penetrating and blunt injuries were covered (Table 2).

Course structure and implementation

The course structure includes an opening session on the first day, didactics, practical sessions, and a closing session on the last day of the course.

Opening session and guest lecture

The opening session consists of a 20–50-question pre-course test, welcome addresses, and a guest lecture. As a channel of grassroots advocacy, and a means of engaging wider society in tackling trauma as a public health menace, the course historically hosted guest lectures during opening ceremonies. Community and religious leaders, academics, representatives of non-governmental organisations and not-for-profits, pressmen, politicians, and military officers have been invited to these events. Table 3 shows the themes of the talks over 8 years. The capital-intensive nature of these opening ceremonies (and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic), however, resulted in suspension of the guest lectures since 2014.

Course didactics and practical low-cost simulation-based education sessions

Didactics, enhanced by audio-visual aids, are facilitated by a wide range of surgical faculty, military personnel, Federal Fire Service professionals, Federal Road Safety Corps officials, anaesthesiologists, obstetrician-gynaecologists, radiologists, forensic pathologists, International Committee of the Red Cross faculty, psychiatrists, and medical educators (Table 2). The breadth and depth of the didactics have been expanded over time based on feedback from participants and course faculty. From an initial 15 lectures, the scope of didactic presentations has increased to 30 over the years, representing a 100% growth in lecture content. Practical demonstrations and hands-on sessions are a critical component of the course (Table 1). Over the years, participant surveys on Kirkpatrick level 1 have shown that these sessions create a high level of engagement.

Concluding session

A 20–50-item post-course test is taken at the conclusion of the course, followed by a post-course survey and focus group discussion aimed at improving subsequent offerings of the course. Themes that have arisen over the years have been suggestions of additional course content, increasing course duration, introduction of additional resource persons and potential institutional collaborations, and commentary on the venue, feeding, and attendance. The course typically closes in a formal ceremony with representatives of the WACS and JUTH management in attendance where certificates of attendance are presented to course participants.

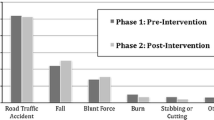

Attendance trends

Course attendance has grown consistently since inception, and in its last offering it has experienced 511% growth from baseline (Table 4), with multidisciplinary expansion (Fig. 2). From 2008 to 2021, 17% (74/439) of attendees were general practitioners (non-specialist physician surgical providers), 20% (88/439) were nurse anaesthetists, 18% (78/439) were perioperative nurses, and 13% (58/439) were critical care providers. In addition, 23% (99/439) of attendees were non-military surgical trainees or consultants and 1% (4/439) were military surgeons from the army, the air force, the navy, and the Nigerian defence headquarters. Over 90% of non-military surgical attendees were junior or senior registrars (specialty trainees). Up to 2% (9/439) were civilian emergency response workers and pre-hospital care staff, while paramilitary medical officers from the police and the Federal Road Safety Commission, and renal nurses, each comprised 1% of learners. There are no undergraduate medical student attendees.

Course evaluation

The course has been assessed on the first and second Kirkpatrick levels as part of an internal audit for several years [20]. The first Kirkpatrick level measures participants’ reactions to the course using post-course surveys and open group discussions on the last day of the course [20]. The second Kirkpatrick level measures learning (knowledge and skill acquisition) using multiple-choice tests [20]. Pre-course and post-course tests are routinely developed by facilitators, reviewed by a panel of three consultants and professors of surgery, and pre-tested by surgery residents and members of the course secretariat. The 20–50-item tests are mapped to course objectives across all areas of learning. Table 5 shows average pre- and post-test scores from 2016 to 2020.

Economics of the course

The WACS/JUTH trauma course is not run with a “for-profit” model. The course is run by charging user fees of about 80 USD per participant for the entire 5-day course, which incorporates feeding, course materials (bags, pens, and customised writing pads), simulation models, disposables (including gloves, sutures, and chest tubes), venue, publicity, video recording, facilitator fees, and honoraria. No grants have supported the training since its inception; however, pharmaceutical and device companies, private hospitals, and individual donors make partial scholarships possible in exchange for sponsorship recognition. Any unused funds are ploughed back into the next year’s course. Many organizations like the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency, the Federal Ports Authority, the Federal Road Safety Corps, the National Emergency Management Agency, the military, the police, and various Hospital Management Boards financially sponsor their staff to participate in the course. The course has been financially sustainable over the years and has never run on a funding deficit.

Communication innovations

Innovations in course content communication and material dissemination has led to migration from provision of rewritable Compact Discs to the use of Dropbox, and later WhatsApp [21, 22]. In the last 3 years, a WhatsApp group to support the learners and mitigate decay of knowledge gained has been created by course organisers. To aid post-course revision, videos of the practical and simulation sessions have also been provided to participants.

Discussion

Similar courses in low- and middle-income settings

The need for trauma education is universal, and various contexts have attempted contextualized trauma training [23]. The International Association for Trauma Surgery and Intensive Care (IATSIC) created a Definitive Surgical Trauma Care course for surgeons inexperienced in trauma that emphasizes surgical technique but has had poor uptake in Low-Income settings due to cost and logistics of set up [23]. The WACS has a matching successful Advanced Trauma Operative Management course hosted in Ghana with an operative emphasis [24]. The National Trauma Management Programme, franchised to the Academy of Traumatology of India and Sri Lankan College of Surgeons, has trained thousands of medical doctors in the initial management and work-up of injured patients in the emergency room successfully in LMICs [23]. Unlike the WACS trauma course, this has been focused only on medical doctors, without recourse to multidisciplinary engagement necessary for holistic trauma care. The Primary Trauma Care (PTC) course is a 2-day, open access course published by the World Health Organization focused on training health care workers in resuscitation and initial management of injured patients with limited resources as a low-cost alternative to the cost intensive ATLS [25]. An advantage of this course over others is that instructors are unpaid, participation is largely free, and it incorporates an instructor course which promotes local ownership and sustainability. Backed by a funded foundation, costs are offset by charity. In contrast to the WACS/JUTH course that has not been replicated beyond Jos, Nigeria for the sub-region, the PTC has been very successful in its spread to 60 countries based on the train-the-trainer model that it employs [25]. Although the WACS course is fully locally inspired and owned, lessons can be learned from the PTC on expanding the influence of the course through deliberately training trainers who can replicate training to other centres in the sub-region. The College of East Central and Southern Africa, for instance has had the PTC course run in over nine countries, which multiplies impact [19, 26]. However, while the PTC course focuses on introducing an ‘ABCDE’ approach to trauma care, the WACS course takes a broader pre-, intra-, and post-hospital care approach, providing basic science knowledge (like the metabolic response to injury), non-surgical education (like trauma forensics, and mental health approach to trauma) and systems approaches (trauma registry development, disaster management). This holistic approach is advantageous but requires more time (5 days) and more resources. Other trauma courses held in LMICs include the Trauma Evaluation and Management course focused largely on medical students, the Better and Systematic Team Training (BEST) course which sought to create trauma committees and registries in Botswana, the Trauma Team Training courses in Guyana and Tanzania, Rural Trauma Team Development Course in India and Pakistan, Acute Trauma Care courses in Zambian and Kenya, Emergency Room Trauma courses in Nepal, and the Kampala Advanced Trauma Course in Uganda, and various pilot courses largely focused on physicians.[19, 24]. A key lesson from this variety of courses is that there is need for trauma training across contexts, and that resource, time availability, sociocultural, and partnership contexts matter. Courses should always be contextualized.

Most of these courses range from $10 USD to $232 USD per participant, excluding the cost of international faculty [19]. Most courses hosted in LMICs are a collaboration between funding HIC partner universities or not-for-profit organizations [19]. This course is one of the very few LMIC trauma courses completely funded from within the host country. Costing $80USD per participant, it offers a reasonable financial alternative to HIC-sponsored courses like the Advanced Trauma Life Support course which requires an over $80,000USD start-up cost and costs a minimum of $182 USD per person [27, 28].

Some lessons learned over years of organizing this course are discussed below.

A focus on multidisciplinary trauma team training

The focus of the course has shifted to include the entire health care team, as team approach has proven to be more effective in similar educational programs [29, 30]. Strengthening health systems must take a holistic approach, and the course has progressively grown to reflect this ideal [31]. Non-physician participation was minimal until 2015, when collaborations were forged with the local school of post-basic nursing studies. Participation of specialist nurses, particularly nurse anaesthetists, critical care nurses, and perioperative care nurses, has been consistently rising since then.

Currently, more complex multidisciplinary expansion of the course is develo** through partnership with the International Committee of the Red Cross. To further target building trauma care capacity in more health professionals, two courses are being developed as offshoots of the trauma management course. These include a contextual Emergency Room Trauma Course dedicated to teaching life-saving skills to low-level health care providers (including community health workers, primary care providers, physician assistants, nurses, emergency medical technicians, general practitioners, and other non-surgical specialists), and a War Surgery Academic Module/postgraduate diploma targeted at surgeons and surgical trainees from multiple sub-specialties [32,33,34]. We recommend that trauma education for LMICs should be carried out with the wider trauma team in mind. In a clinical environment that is often marked by occupational rivalry and unhealthy interprofessional workplace competition, team trainings are an important step towards improved teamwork and communication. Similar patterns have been successfully used across nine countries in Eastern, Central and Southern Africa [31, 35, 36].

The strength of multi-institutional collaboration

Collaboration between the WACS and a local teaching hospital is key to the sustainability and reach of the course [17, 35]. While JUTH provides the course context, WACS provides a wider reach and regional legitimacy for the course. Similar collaborations in East, Central, and Southern Africa between the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa and national surgical societies has led to many successful essential surgical skills trainings. Evidence from a sco** review of trauma training courses and programmes in LMICs by Livergant et al. shows that trauma courses should be in response to local need, led by local champions, and nested in a cohesive system [37]. The WACS/JUTH trauma management course represents this dynamic.

The value of public engagement for advocacy for policy change

The opening ceremonies provided an opportunity for community engagement as part of the course. Grassroots advocacy for trauma care must be considered by groups organizing trauma courses in sub-Saharan Africa [38]. Such initiatives should be considered as they create avenues for critical self-reflection, identification of partners and building of coalitions, highlighting of surgical issues, dialogue with policy makers, organization of public interactions, and creation of public solidarity for the cause of global surgical trauma care [38].

The need for consistent course evaluation

The importance of consistent and higher-level evaluation of the translation of knowledge into good patient outcomes has been emphasised in literature [39, 40]. Yearly course evaluations have contributed to improvements in the course structure over time. Every year there has been a significant increase in post-test scores compared to pre-test scores. Course evaluations at higher Kirkpatrick levels to assess behavioural change and change in organizational practice are yet to be performed but are being planned [20]. Long-term knowledge retention and impact on clinical care and clinical outcomes need to be evaluated in addition to short-term knowledge gain as implementation is the focus of trauma management care training [40, 41].

The value of practical low-cost, low-tech simulation-based learning [35, 42, 43]

Trauma courses in LMIC contexts can be effectively run without high-cost simulation models [19, 43]. Our effective use of animal models, low-cost bench top models, low-fidelity mannequins, and human volunteers is an example of how training should not be deterred by limited resources.

Future trends

Looking forward, the course aims to contribute to the development of nationwide trauma registries and training of innovative emergency medical services (EMS) providers in dispatch, field triage, and transport. There is also the potential for expansion into Nigerian military personnel training in response to the desire of the Nigerian Army to arrange such a course prior to deployment of officers to crisis areas around Africa [44]. We also hope to champion cooperation between trauma system hospitals and encourage systematic inter-facility transfer [45, 46]. In addition, a curriculum around the psychiatric aspects of trauma and rape care are being developed in partnership with relevant non-governmental organisations. The college has considered making the course compulsory training for all membership examinations as trauma management is essential surgical care in LMICs, and more surgical trainees are showing interest in trauma care [47].

Furthermore, collaboration with the International Committee of the Red Cross is in progress, aimed at integrating the course into a contextualized War Surgery Academic Module [33, 34]. This will comprise both a university-based academic module for trainee surgeons and a more multidisciplinary postgraduate diploma. This collaboration will expand the course to include training in trauma surgical procedures like surgical debridement, limb amputation, external fixation, thoracotomy, sternotomy, cardiac access and sutures, and interdental wiring among other interventions.

In the future, the course is looking to provide and fully virtual courses and blended learning which shows consistently better effects in systematic reviews and meta-analysis on knowledge gain when compared to traditional learning in health education [48]. In terms of course evaluations, longer-term assessments to measure the impact of the course on participants practice and sending institutions beyond knowledge gain are being planned.

Conclusions

Now in its sixteenth offering, the WACS/JUTH Trauma Management Course has contributed to the training and Continuing Professional Development of over 1288 learners and facilitators in trauma care and can serve as a model for consistent multidisciplinary trauma education in the LMIC setting. As James Styner’s tragedy inspired an internationally recognized standard for the initial assessment and management of the severely injured patient [49], so the tragedy of many unnamed ‘James Styners’ from the political-ethno-religious Jos civilian crises has inspired the development of the WACS/JUTH Trauma Management Course. Our projection for the future is not only to develop human capacity in trauma care for the sub-region, but also to contribute to the development of a trauma system on a broad West African scale that will reduce death and disability following injury. The regional challenges with terrorism and violence continue to make this work relevant [50].

References

Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L et al (2015) Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet 158(1):3–6

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258):1204–1222

Farmer PE, Kim JY (2008) Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg 32(4):533–536

Ekeke ON, Okonta KE (2017) Trauma: a major cause of death among surgical inpatients of a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Pan Afr Med J 28:6

Collaborative E-T, Odland ML, Abdul-Latif AM et al (2022) Equitable access to quality trauma systems in low-income and middle-income countries: assessing gaps and develo** priorities in Ghana, Rwanda and South Africa. BMJ Glob Health 7(4):e008256

Alayande B, Chu KM, Jumbam DT et al (2022) Disparities in access to trauma care in sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Curr Trauma Rep 8(3):66–94

Hollis SM, Amato SS, Bulger E et al (2021) Tracking global development assistance for trauma care: a call for advocacy and action. J Glob Health 11:04007

Government of Plateau State (2020) https://www.plateaustate.gov.ng/plateau/at-a-glance. Accessed 13 Nov 2022

Vahyala AT (2021) Dissecting management strategies of farmer-herder conflict in selected vulnerable states in North-Central Nigeria. Gusau Int J Manag Soc Sci 4(2):25

Ozoilo KN, Pam IC, Yiltok SJ et al (2013) Challenges of the management of mass casualty: lessons learned from the Jos crisis of 2001. World J Emerg Surg 8(1):44

Ozoilo K, Amupitan I, Pam IC et al (2014) The mass casualty from the Jos crisis of 2008: the pains and gains of lessons from the past. Niger J Ortho Trauma 13(1):1–5

Ozoilo KN, Amupitan I, Peter SD et al (2016) Experience in the management of the mass casualty from the January 2010 Jos Crisis. Niger J Clin Pract 19(3):364–367

Nwadiaro HC, Iya D, Yiltok SJ et al (2003) Mass casualty management: Jos University Teaching Hospital experience. West Afr J Med 22(2):199–201

Nwadiaro HC, Yiltok SJ, Kidmas AT (2000) Immediate mass casualty management in Jos University Teaching Hospital: a successful trial of Jos protocol. West Afr J Med 19(3):230–234

Ozoilo KN, Ali M, Peter S et al (2015) Trauma registry development for Jos University Teaching Hospital: report of the first year experience. Indian J Surg 77(4):297–300

Nimlyat PS, Kandar MZ, Sediadi E (2015) Empirical investigation of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) performance in hospital buildings in Nigeria. Jurnal Teknologi 77(14):41–50

Yawe KT (2020) West African College of Surgeons and its role in global surgery. Bull Am Coll Surg. https://bulletin.facs.org/2018/05/west-african-college-of-surgeons-and-its-role-in-global-surgery/. Accessed 21 Mar 2021

Ozoilo KN, Kidmas AT, Nwadiaro HC et al (2014) Management of the mass casualty from the 2001 Jos crisis. Niger J Clin Pract 17(4):436–441

Brown HA, Tidwell C, Prest P (2022) Trauma training in low- and middle-income countries: a sco** review of ATLS alternatives. Afr J Emerg Med 12(1):53–60

Kirkpatrick D (1998) Evaluating training programs: the four levels. Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco

Dropbox Inc (2021) Dropbox. https://dropbox.com. Accessed 21 Mar 2021

WhatsApp Inc (Facebook, Inc.) (2021) WhatsApp. https://whatsapp.com. Accessed 13 Nov 2022

Mock C (2016) International association for trauma surgery and intensive care (IATSIC) presidential address: improving trauma care globally: How is IATSIC doing? World J Surg 40:2833–2839

Jacobs LM, Burns KJ, Luk SS et al (2005) Advanced Trauma Operative Management course introduced to surgeons in West Africa. Bull Am Coll Surg 90(6):8–14

Kamran Bakhshi S, Jooma R (2019) Primary trauma care: a training course for healthcare providers in develo** countries. J Pak Med Assoc 69(Suppl 1):S82–S85

Ologunde R, Le G, Turner J et al (2017) Do trauma courses change practice? A qualitative review of 20 courses in East, Central and Southern Africa. Injury 48(9):2010–2016

Kornfeld JE, Katz MG, Cardinal JR et al (2019) Cost analysis of the Mongolian ATLS© Program: a framework for low- and middle-income countries. World J Surg 43:353–359

Quansah R, Abantanga F, Donkor P (2008) Trauma training for nonorthopaedic doctors in low- and middle-income countries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466(10):2403–2412

McLaughlin C, Barry W, Barin E et al (2019) Multidisciplinary simulation-based team training for trauma resuscitation: a sco** review. J Surg Educ 76(6):1669–1680

Peter NA, Pandit H, Le G et al (2016) Delivering a sustainable trauma management training programme tailored for low-resource settings in East, Central and Southern African countries using a cascading course model. Injury 47(5):1128–1134

Bach JA, Leskovan JJ, Scharschmidt T et al (2017) The right team at the right time—multidisciplinary approach to multi-trauma patient with orthopedic injuries. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 7(1):32–37

Tenner AG, Sawe HR, Amato S et al (2019) Results from a World Health Organization pilot of the Basic Emergency Care Course in Sub Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 14(11):e0224257

Giannou C, Baldan M (2020) War surgery: working with limited resources in armed conflict and other situations of violence, vol 1. International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva

Giannou C, Baldan M, Molde Å (2013) War surgery: working with limited resources in armed conflict and other situations of violence, vol 2. International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva

Peter NA, Pandit H, Le G et al (2015) Delivering trauma training to multiple health-worker cadres in nine sub-Saharan African countries: lessons learnt from the COOL programme. Lancet 385(Suppl 2):S45

Nogaro MC, Pandit H, Peter N et al (2015) How useful are Primary Trauma Care courses in sub-Saharan Africa? Injury 46(7):1293–1298

Livergant RJ, Demetrick S, Cravetchi X et al (2021) Trauma training courses and programs in low- and lower middle-income countries: a sco** review. World J Surg 45(12):3543–3557

Jumbam DT, Kanmounye US, Alayande B et al (2022) Voices beyond the Operating Room: centring global surgery advocacy at the grassroots. BMJ Glob Health 7(3):e008969

Mock CN, Quansah R, Addae-Mensah L et al (2005) The development of continuing education for trauma care in an African nation. Injury 36(6):725–732

Shanthakumar D, Payne A, Leitch T et al (2021) Trauma care in low- and middle-income countries. Surg J (NY) 7(4):e281–e285

Olufadeji A, Usoro A, Akubueze CE et al (2021) Results from the implementation of the World Health Organization Basic Emergency Care Course in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr J Emerg Med 11(2):231–236

Kurdin A, Caines A, Boone D et al (2018) TEAM: a low-cost alternative to ATLS for providing trauma care teaching in Haiti. J Surg Educ 75(02):377–382

Pringle K, Mackey JM, Modi P et al (2015) A short trauma course for physicians in a resource-limited setting: Is low-cost simulation effective? Injury 46(9):1796–1800

Hailu S (2020) Modern peace kee** in Africa: Lessons from Nigeria. J Afr Policy Stud 26(1):69–86

Okereke IC, Zahoor U, Ramadan O (2022) Trauma care in Nigeria: time for an integrated trauma system. Cureus 14(1):e20880

Gwaram UA, Okoye OG, Olaomi OO (2021) Observed benefits of a major trauma centre in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Afr J Emerg Med 11(2):311–314

Okoye O, Ameh E, Ojo E (2021) Perception and attitude of surgical trainees in Nigeria to trauma care. Surg Res Pract 2021:6584813

Vallée A, Blacher J, Cariou A et al (2020) Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 22(8):e16504

Carmont MR (2005) The Advanced Trauma Life Support course: a history of its development and review of related literature. Postgrad Med J 81(952):87–91

Akanji OO (2019) Sub-regional security challenge: ECOWAS and the war on terrorism in West Africa. Insight Afr 11(1):94–112

Funding

No funding or research support has been obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing funding, employment, financial or non-financial interest directly or indirectly related to this manuscript to declare.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Jos University Teaching Hospital Ethical Review Committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants in any part of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sule, A.Z., Alayande, B.T., Ojo, E.O. et al. The History and Evolution of the West African College of Surgeons/Jos University Teaching Hospital Trauma Management Course. World J Surg 47, 1919–1929 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07004-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07004-6