Abstract

Understanding the pricing and operation mechanism of community mental health (CMH) providers is important for designing effective health care policies as the CMH system has been playing an essential role in providing mental health services. This paper studies the delivery of community-based mental health care and interdependence among CMH providers by investigating the pricing patterns of CMH providers in the Detroit-Wayne County of Michigan. We employ a spatial dynamic panel data model with interactive fixed effects to identify the strategic interactions among the providers, along both dimensions of time-series and cross-section spatial variations. We find evidence for significant spatial interdependence among the CMH providers, even after controlling for the interactive fixed effects. In contrast, the coefficient on the spatial-dynamic term is insignificant, suggesting that no time-space simultaneous effects exist. We also find the pure dynamic effect to be positive and significant. These findings provide important implications for mental health care policy and practice decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

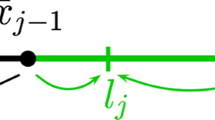

The time-space simultaneous effects refer to the effects of the spatial-dynamic term \(W_N Y_{N,T-1}\), which capture the time lagged spatial spillover effect from neighboring providers.

Anselin et al. (2008) provides a list of spatial panel data models and presents the corresponding likelihood functions. Lee and Yu (2010a), Lee and Yu (2015) review some recent development in econometric specification and estimation of spatial panel data models for both static and dynamic cases and investigate asymptotic properties of estimators.

The five most costly conditions were: heart disease, trauma-related disorders, cancer, mental disorders and asthma. See Figure 3 for the expenditure data for the five most costly conditions.

Please check http://www.nasmhpd.org for more information.

Currently Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority.

The two primary sources of public mental health funding are Medicaid and state general funds, accounting for 90% of the system on average. The rest 10% is funded by Medicare, federal block grant funds, which are not tracked under the Agency (NAMI 2010).

Fiscal year (FY). A fiscal year is used because the funding budget is made by both the federal and state governments based on the calendar of a fiscal year which begins on October 1 of the previous calendar year and ends on September 30 of the year which is numbered.

Shi and Lee (2018) employ a similar model to study the effects of gun control on crime rates among US states.

In contrast, the usual time fixed effect specification assumes the effect of time trend to be constant across individual units. And compared with the random effects specification which assumes no correlations between the common factor components and the regressors, the fixed effects approach allows unknown and flexible correlations between them.

Many studies have provided evidence for heterogeneous time-varying factors in a variety of settings. In particular, Shi and Lee (2017) suggest that states with and without right-to-carry laws may have different political preferences and other time-varying social economic characteristics, and thus may follow different time trends. Kim and Oka (2014) point out that unobserved heterogeneity such as demographic structure, stigma of divorce, religious beliefs and other cultural factors may develop over time and vary to a large extent across states. As a result, these factors may generate heterogeneous impacts on both divorce rates and divorce law reforms across states. Bai (2009) argues that unobservable characteristics including innate ability, perseverance, and motivation may vary across age cohorts and affect individuals heterogeneously.

In the literature, several approaches have been proposed, including the information criteria in Bai and Ng (2002), the eigenvalue differences criterion in Onatski (2010), as well as the methods proposed in Alessi et al. (2010), to name a few. However, as demonstrated in Ahn and Horenstein (2013), the eigenvalue ratio and growth ratio criteria have very nice property, generally outperforming competing estimators. In particular, the estimators proposed in Bai and Ng (2002) are sensitive to the choice of \(r_{\mathrm{max}}\).

In our sample, N=182, T=4, so we set \(r_{\mathrm{max}}=3\).

The service codes follow the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code set issued annually by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

ICD-9 codes.

Medicaid and state general fund dollars are two primary sources of funding for public mental health services. In the state of Michigan, individuals who are eligible for Supplemental Security Income are automatically eligible for Medicaid. State mental health budgets are primarily funded by state general fund dollars to provide state hospital and inpatient care, crisis services and community mental health services for individuals with mental disorders.

CMHSP Sub-element Cost Reports for Section 404, available at http://www.michigan.gov/mdch.

Available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

ICD-9 codes 293.83, 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.40, 311.00.

ICD-9 codes 293.81, 293.82, 295.xx, 297.00, 297.10, 297.20, 297.30, 297.80, 297.90, 298.00, 298.10, 298.20, 298.30, 298.40, 298.80, 298.90.

As pointed out in Brueckner (2003), such spatial interdependence among individual agents may arise from either spillover effect or the resource flow across agents.

We follow LeSage and Pace (2009) to calculate the direct effect for spatial models. Specifically, for provider i, the direct effect of changing the \(k^{\mathrm{th}}\) explanatory variable \(x_{\mathrm{ik}}\) on \(y_i\) includes both own effect and the feedback effects from paths where the unit i affects unit j which in turn also affects unit i, i.e., \(i \rightarrow j \rightarrow i\), as well longer loops such as \(i \rightarrow h \rightarrow j \rightarrow i\), and so on, which can be calculated as: \(\frac{\partial y_i}{\partial x_{\mathrm{ik}}}=S_N (\lambda )_{\mathrm{ii}} \beta _k\), where \(S_N (\lambda )_{\mathrm{ii}}\) denotes the i th diagonal element of the matrix \(S_N (\lambda )=(I_N-\lambda W_N)^{-1}\). Therefore, the average direct effect is given by \(\frac{1}{N} tr(S_N (\lambda )) \beta _k\). It turns out that the corresponding marginal effect of the Number of patients served based on this calculation is roughly the same as the estimated coefficient of 0.0007.

To save space, we only report the results for the SDPD with interactive fixed effects.

References

Ahn SC, Horenstein AR (2013) Eigenvalue ratio test for the number of factors. Econometrica 81(3):1203–1227

Alcacer J, Dezso C, Zhao M (2015) Location choices under strategic interactions. Strateg Manag J 36(2):197–215

Alessi L, Barigozzi M, Capasso M (2010) Improved penalization for determining the number of factors in approximate factor models. Statist Probab Lett 80(23–24):1806–1813

Anselin L (1988) Spatial econometrics: methods and models. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Anselin L (2001) Spatial econometrics. In: Baltagi Badi H (ed) A companion to theoretical econometrics. Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Massachusetts

Anselin L, Le Gallo J, Jayet H (2008) Spatial panel econometrics. The econometrics of panel data. Springer, Berlin, pp 625–660

Bai J (2009) Panel data models with interactive fixed effects. Econometrica 77(4):1229–1279

Bai J, Ng S (2002) Determining the number of factors in approximate factor models. Econometrica 70(1):191–221

Baicker K (2005) The spillover effects of state spending. J Public Econ 89:529–544

Bergstrom P, Dahlberg M, Mork E (2004) The effects of grants and wages on municipal labour demand. Labour Econ 11:315–334

Bivand R, Szymanski S (1997) Spatial dependence through local yardstick competition: theory and testing. Econ Lett 55:257–265

Brueckner JK (1998) Testing for strategic interaction among local governments: the case of growth controls. J Urb Econ 44(3):438–467

Brueckner JK (2003) Strategic interaction among governments: an overview of empirical studies. In Reg Sci Rev 26(2):175–188

Brueckner JK, Saavedra LA (2001) Do local governments engage in strategic property-tax competition? Natl Tax J 54(2):203–239

Buck JA (2003) Medicaid, health care financing trends, and the future of state-based public mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 54(7):969–975

Buckingham B, Burgess PP, Solomon S, Pirkis J, Eagar K (1998) Develo** a casemix classification for mental health services: summary. Report of a project funded by the Australian department of health & family services under the national mental health strategy and the casemix development program. Available at http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-d-casemix

Buckingham B, Burgess P, Case AC, Hines JR Jr, Rosen HS (1993) Budget spillovers and fiscal policy interdependence: evidence from the States. J Public Econ 52:285–307

Cliff AC, Ord JK (1973) Spatial autocorrelation. Pion Limited, London

Cohen JW, Spector W (1996) The effect of Medicaid reimbursement on quality of care in nursing homes. J Health Econ 14:23–48

Dahlberg M, Johansson E (2000) An examination of the dynamic behaviour of local governments using GMM bootstrap** methods. J Appl Econ 15:401–416

Drake R, Latimer E (2012) Lessons learned in develo** community mental health care in North America. World Psychiatr 11(1):47–51

Dranove M, Ludwick R (1999) Competition and pricing by nonprofit hospitals: A reassessment of Lynk’s analysis. J Health Econ 18:87–98

Dougherty R (2011) Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency: MCPN options for redesign. Available at http://www.vceonline.org/resource/attach/1048/DWCCMHAMCPNRedesignreport.pdf

Eagar K, Gordon R, Green J, Smith M (2004) An Australian casemix classification for palliative care: lessons and policy implications of a national study. Palliat Med 18(3):227–233. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216304pm876oa

Elhorst JP (2003) Specification and estimation of spatial panel data models. Int RegSci Rev 26:244–268

Garfield RL, Zuvekas SH, Lave JR, Donohue JM (2011) The impact of national health care reform on adults with severe mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 168(5):486–494. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060792

Greenwood N, Chriholm B, Burns T, Harvey K (2000) Community mental health team case-loads and diagnostic case-mix. Psychiatr 24:290–293

Koenig L, Fields EL, Dall TM, Ameen AZ, Harwood HJ (2000) Using Case-Mix Adjustment Methods To Measure the Effectiveness of Substance Abuse Treatment: Three Examples Using Client Employment Outcomes. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment

Kim D, Oka T (2014) Divorce law reforms and divorce rates in the USA: an interactive fixed effects approach. J Appl Econ 29:231–245

Keeler E, Melnick G, Zwanziger J (1999) The changing effects of competition on non-profit and for-profit hospital pricing behavior. J Health Econ 18:69–86

Kessler RC, Roger LB, Clifford LB (1981) Sex differences in psychiatric help-seeking: evidence from four large scale surveys. J Health Soc Behav 2:49–64

Krouse GC (1990) Theory of industrial economics. Basil Blackwell, Cambridge

Lee LF, Yu J (2010a) Some recent developments in spatial panel data models. Reg Sci Urb Econ 40:255–271

Lee LF, Yu J (2010b) Estimation of spatial autoregressive panel data models with fixed effects. J Econ 154:165–185

Lee LF, Yu J (2010c) A spatial dynamic panel data model with both time and individual fixed effects. Econ Theory 26(2):564–597

Lee LF, Yu J (2015) Spatial Panel Data Models. In: Baltagi B (ed) Oxford handbook of panel data. Oxford University Press, Oxford

LeSage JP, Pace RK (2009) Introduction to spatial econometrics. Taylor & Francis, London

Lundberg J (2006) Spatial interaction model of spillovers from locally provided public services. Reg Stud 40(6):631–644

Lynk WJ (1995) Nonprofit hospital mergers and the exercise of market power. J Law Econ 38:437–461

Mann C (2012) Coverage and service design opportunities for individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders. Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services information bulletin. Available at http://medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance

Maynard C, Ehreth J, Cox GB, Peterson PD, McGann ME (1997) Racial differences in the utilization of public mental health services in Washington State. Adm Policy Ment Health 24, 411–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02042723

McGuire T, Miranda J (2008) New evidence regarding racial and ethnic disparities in mental health: policy implications. Health Aff 27:393–403

Mobley L (2003) Estimating hospital market pricing: an equilibrium approach using spatial econometrics. Reg Sci Urb Econ 33:489–516

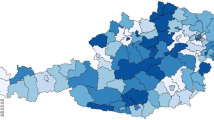

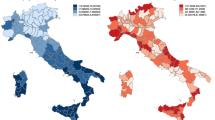

Moscone F, Knapp M (2005) Exploring the spatial pattern of mental health expenditure. J Ment Health Policy Econ 8:205–217

Moscone F, Tosetti E, Knapp M (2007a) SUR model with spatial effects: an application to mental health expenditure. Health Econ 16:1403–1408

Moscone F, Knapp M, Tosetti E (2007b) Mental health expenditure in England: a spatial panel approach. J Health Econ 26:842–864

Moscone F, Tosetti E (2010) Health expenditure and income in the United States. Health Econ 19:1385–2010

National Alliance on Mental Illness (2010) Public mental health service funding: an overview. Available at http://www.nami.org/Content/NavigationMenu/State_Advocacy

Onatski A (2010) Determining the number of factors from empirical distribution of eigenvalues. Rev Econ Stat 92(4):1004–1016

Rassenti S, Reynolds S, Smith V, Szidarovszky F (2000) Adaptation and convergence of behavior in repeated experimental Cournot games. J Econ Behav Org 41:117–146

Revelli F (2006) Performance rating and yardstick competition in social service provision. J Public Econ 90:459–475

Schulz A, Williams D, Israel B, Becker A, Parker E, James S, Jackson J (2000a) Unfair treatment, neighborhood effects, and mental health in the Detroit metropolitan area. J Health Soc Behav 41(3):314–332

Schulz A, Israel B, Williams D, Parker E, Becker B, James S (2000b) Social inequalities, stressors and self-reported health status among African American and white women in the Detroit metropolitan area. Soc Sci Med 51:1639–1653

Shirk C (2008) Medicaid and Mental Health Services. National Health Policy Forum, Background Paper No. 66. Available at www.nhpf.org/pdfs_bp/BP66_Medicaid_&_Mental_Health_10-23-08.pdf

Soni A (2015) Trends in the five most costly conditions among the U.S. Civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2002 and 2012. Statistical Brief #470 of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Available at https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st470/stat470.pdf

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012) Mental Health, United States, 2010. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4681. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Tao J, (2005) manuscript. Analysis of local school expenditures in a dynamic game. Manuscript. Department of Economics. Ohio State University

Thornicroft G, Alem A, Dos Santos R et al (2010) WPA guidance on steps, obstacles and mistakes to avoid in the implementation of community mental health care. World Psychiatry 9(2):67

Shi W, Lee LF (2017) Spatial dynamic panel data models with interactive fixed effects. J Econ 197:323–347

Shi W, Lee LF (2018) The effects of gun control on crimes: a Spatial interactive fixed effects approach. Empir Econ 55(1):233–263

Yu Y, Zhang L, Li F, Zheng X (2013) Strategic interaction and the determinants of public health expenditures in China: a spatial panel perspective. Ann Reg Sci 50(1):203–221

Yu J, de Jong R, Lee LF (2008) Quasi-maximum likelihood estimators for spatial dynamic panel data with fixed effects when both N and T are large. J Econ 146:118–134

Wayne State University Project CARE (2011) Needs Assessment 2010 and 2011. A report presented to Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency

Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C (2001) Ethnic Disparities in Unmet Need for Alcoholism, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Care. American J Psych 158(12):2027–2032

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the editor, Janet E. Kohlhase, and one anonymous referee for very helpful comments. We also thank the Detroit Wayne Mental Health Authority for giving us consent to use the data and adequate resources to conduct the analysis. We are grateful to Allen Goodman for valuable comments and to Shi Wei and Jihai Yu for help on Matlab codes. All remaining errors are our own.

X. Lin: Most of the work was done during the author’s visit to Zhongnan University of Economics and Law. L. Wu: At the time this study was mostly completed, Lizi Wu was a PhD candidate at Wayne State University, and she is currently Data Analyst at Optum.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 7, 8, 9 and Figs. 3, 4.

Source: Center for Financing, Access, and Cost Trends, AHRQ, Household Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2002 and 2012, https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st470/stat470.pdf#search=%20Five%20Most%20Costly%20Conditions

Expenditures for the five most costly conditions, 2002 and 2012.

Distribution of mental health expenditures by type of service, 1986 & 2014. Exclude spending on insurance administration. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4883.pdf

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, X., Wu, L. Interdependence among mental health care providers: evidence from a spatial dynamic panel data model with interactive fixed effects. Ann Reg Sci 67, 131–165 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01043-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-020-01043-w