Abstract

Previous studies have examined how cash transfers affect children’s education and health regardless of sibship size. I examine the long-run consequences of a Dutch reform that gradually curtailed child-benefit payments for larger families. Based on administrative data and a regression discontinuity design, I find little evidence of average reform effects on children’s education and mental health. However, children in less well-off households exposed to the reform experience long-lasting educational penalties. Analyses of survey and admin data suggest that, if not for the reform, households would have relied more on centre-based care as opposed to maternal care. Lower parental investments in child-related goods and a more stressful environment accompanied heightened poverty risks after the reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

How to subsidise families with young children is a long-standing concern for scientists and policymakers (Becker and Lewis 1973; Cremer et al. 2003; Cigno et al. 2004; Wolf et al. 2011; Werding 2014). Research has shown that benefit programs supporting household incomes can lift families out of poverty, boost fertility, and improve child outcomes in domains such as education and health in the short and long run (Milligan 2005; Milligan and Stabile 2011; Dahl and Lochner 2012; Fox and Burns 2022; González and Trommlerová 2021; Barr et al. 2022; Baker et al. 2023). Among these programs, child benefits are a widely adopted cash transfer aimed at families with young children. In 2019, EU-27 countries allocated an average of 1.2% of GDP to such unconditional cash transfers (EUROSTATFootnote 1). Child benefits, which are often universal, are also one of the few benefit programs with close to full take-up (cf. Ko and Moffitt 2022).

Despite their documented successes, however, child benefits have had different configurations over time and have not been the subject of long-run evaluations. At their inception in the 1940 s, many child-benefit schemes in Europe were first targeted exclusively to families with two or more children. Eligibility was later expanded to all families, regardless of the number of children, but larger families kept receiving more generous payments than one-child families for decades (Bradshaw and Finch 2002; Riphahn and Wiynck 2017; Stewart et al. 2023). Boosting benefits with the number of children might counter the dilution of resources across siblings in larger families and relieve poverty risks and related stress. On the other hand, as sibship size grows, the effectiveness of increasing subsidies might decline due to scale economies within the household (cfr. Cremer et al. 2003; Cigno et al. 2004). In line with this second line of thinking, a raft of cutbacks has slashed the entitlements of larger families in the 1990 s and in recent years in European countries. Relatively overlooked, such cutbacks might have (had) far-reaching implications for child outcomes, household behaviour, and inter- and intra-household disparities by sibship size and birth order.

This paper examines the intergenerational effects of child-benefit design in relation to sibship size, focusing on a 1994 reform of the Dutch universal child-benefit system. In the Netherlands, like in other European countries, child-benefit amounts were once topped up with each parity after the first. With the reform, per-child amounts ceased to increase with each additional child starting from those born on 1 January 1995. The cutback was thus distributed over children’s entire eligibility period, i.e. up to age 18, and amounted each year to at least 2% of disposable income in less well-off households. Cumulatively, the induced income shock was multiple times the size of policies investigated in previous studies (Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Barr et al. 2022). Based on the reform’s date-of-birth cutoff and high-quality administrative data (Bakker et al. 2014), I use a regression discontinuity design to investigate reform effects on children’s human capital across the education and health domains. I complement the evidence on child outcomes by analysing possible mechanisms in affected households with administrative data and multiple household surveys.

There are three main findings. First, I find little evidence of average long-run effects on children narrowly exposed to the policy change, either in terms of educational enrolment in secondary school and postsecondary attainment or mental healthcare use and clinical diagnoses in late adolescence and early adulthood. Second, there is some evidence that children in less well-off households have lower educational attainment when exposed to the reform. In particular, second and higher-order children are less likely to enrol in the academic track of Dutch secondary school. This penalty stands after numerous robustness and sensitivity checks, including for multiple testing, and is also accompanied by lower earnings in early adulthood. Third, these effects can be attributed to household responses induced by the reform. Larger families experienced more persistent income poverty and lowered investments in child-related goods whilst relying more on economies of scale. On top of this income effect, the reform raised the costs of centre-based care, which households substituted with more maternal time at home rather than in paid work. Albeit more mixed, evidence also suggests that these changes may have destabilised relationships within the household. In sum, children in less well-off households would have benefited from more centre-based care, larger monetary investments, and less stressful household environments, if not for the reform.

My first contribution is to expand current knowledge on the long-run intergenerational effects of cash transfers in high-income countries (Heckman and Mosso 2014; Cooper and Stewart 2021). Most studies in the field have examined benefit expansions rather than cutbacks, often concentrating on in-work benefits targeted to lower-income households in the US (e.g. Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Barr et al. 2022). The few studies on child-benefit expansions have focused on their short-run effects (Milligan and Stabile 2011). Cutbacks have been prominent outside the US, most recently after the Great Recession. Few studies have looked into the household-level consequences of cutbacks, and reforms passed in the 2010 s are too recent to allow for long-run evaluations (cf. Reader et al. 2022). Effects on children’s education in this study suggest that cutbacks like the 1994 Dutch child-benefit reform may have detrimental consequences that are symmetric to, and at least as large as, the positive impacts of benefit expansions (Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Barr et al. 2022). Importantly, these shifts in educational attainment are observed in the context of a fairly generous safety net (e.g. De Nardi et al. 2021) and might thus provide a lower bound for effects in less protective social security systems (e.g. the “two-child limit” introduced in 2017 in the UK, Reader et al. 2022). In short, I provide one of the first causal and long-run evaluations of cutbacks to a universal and unconditional family cash transfer, using the Dutch case as a litmus test for policy effects on children and households.

In addition, this study provides empirical evidence that can inform the design of child benefits and similar policies in relation to sibship size (Cremer et al. 2003; Cigno et al. 2004). The reform taxed parents in terms of exposure to poverty risks and lower maternal earnings. Shifts in children’s educational attainment and lower earnings at labour market entry also suggest that the reform will tax their lifetime earnings (Borghans et al. 2019), although the latter remains a topic for future studies when more data will be available. If further confirmed, the economic costs of the reform will not only be borne by households but will also weigh on public finances (e.g. Blanden et al. 2010), thereby calling into question the economic rationale for cutbacks. At the household level, my findings also suggest that incentivising parents to adjust by having fewer children or relying more on scale economies might be ineffective or even detrimental, especially in families that are already less well-off.

Last, this study speaks to debates on the importance of family income and related policies for children’s human capital (e.g. Mayer 1997; Dahl and Lochner 2012; Heckman and Mosso 2014; Carneiro et al. 2021). Different from educational outcomes, I find inconclusive results on whether an income shock gradually accumulating over time might affect children’s (and parental) mental health. One interpretation is that small and piecemeal income changes do not move the needle for these outcomes compared to larger and/or more concentrated shocks provided by policies previously examined in the literature (Milligan and Stabile 2011; Boyd-Swan et al. 2016). As for children’s education, I find that children born around the cutoff are already affected by the time they are enrolled in secondary school. Evidence on child-related investments suggests that even small cutbacks may reduce early parental investments in less well-off households and hinder, thereby, skill accumulation (Barr et al. 2022). These findings echo and complement evidence on the productivity of family income over children’s lifetime, which recent studies indicate might follow a U-shaped pattern with the highest returns in early childhood (Carneiro et al. 2021). Overall, this study offers further evidence that policies supporting family income can affect parents and children, yet much might depend on the size, timing, and mechanisms tied to policy-driven income changes (Milligan and Stabile 2011; Dahl and Lochner 2012; Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Barr et al. 2022).

2 Background

2.1 The 1994 reform of the Dutch child-benefit system

Child benefit (Kinderbijslag) was first instituted in the Netherlands in 1941 and then incorporated in the so-called Algemene Kinderbijslagwet or General Child Benefit Act in 1962. Similar to other countries, the Dutch child benefit is an unconditional and universal cash transfer to families with young children. Estimates suggest that the benefit covers around “one quarter of the real costs of bringing up a child, ranging from 41% for low-income families to 17% for high-income families” (Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport and Ministry of Education, Culture & Science 2000: 49). Payments have a quarterly frequency, and there are no work mandates or other conditionalities imposed on parents. In fact, all families with young children are eligible, indicating virtually full take-upFootnote 2 as long as they are enrolled in the national insurance scheme (mandatory for residents). The number of registered beneficiaries and that of eligible households are both equal to around 1.8 million households.Footnote 3

Up to 1995, benefit amounts varied by children’s age (with four age groups since 1983: 0–5, 6–11, 12–17, and 18–24) and sibship size in the previous quarter. A reform passed on 22 December 1994 changed the computation of benefits, motivated by the desire to rein in the public budget and shift responsibilities from the state to the individual/household.Footnote 4 The amended law prescribes that all families stop receiving payments after the 18th birthday of the child. In addition, families with two or more children no longer receive a top-up on the benefit rate for each child, effectively resulting in a new scheme in which benefit rates only vary by children’s age. The new scheme applies to all second and subsequent children born from 1 January 1995 onwards. Differently, families with a second or higher-order child born before 1 January 1995 have continued to receive benefits under the old system until the child’s 18th birthday. The old system thus ceased to be operative in 2013.

Figure 1 depicts benefit amounts in 2018 euros (EUR) for the pre- and post-reform system for households with up to four children. Rates on the left-hand side refer to children born (in the 3 monthsFootnote 5) before 1 January 1995. The right panel provides benefit rates for children born under the new system. In short, the reform substituted a system in which per-child allowances would be topped up with each additional child, with one in which per-child amounts remain the same regardless of the number of children.

Quarterly child benefit rates before and after the 1994 reform (EUR, 2018 prices). Own elaboration. Source: https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-1996-243-p17-SC7696.html (last accessed on 6 June 2022)

Some examples best illustrate the monetary difference between the two systems. Table 1A in the Appendix provides back-of-the-envelope calculations for the cumulative losses experienced by hypothetical households with a 2nd, 3rd, or 4th child born at different sides of the policy cutoff. Total yearly losses for families with children born in or after 1995 range from 292 EUR to 998 EUR, whilst losses accumulating until each child reaches age 18 range from around 5,260 EUR to 17,966 EUR, for two-child and four-child families, respectively. In line with these computations, Fig. 1A in the Appendix displays losses of around 200 EUR per child per year for families affected by the reform, based on survey dataFootnote 6 collected in the period 1988–2002 (CBS Budgetonderzoek, Budget Survey; see Appendix A for details).

For reference, a 200 EUR yearly cut (lower bound) would correspond to a loss of around 2% of annual disposable income for families in the bottom 10% of the household income distribution in 1995 (10th percentile \(\approx \) 11,500 EUR in 2018 prices, Vrooman and Hoff 2004). As for common child-related expenses, a loss of 200 EUR equals more than three times the minimum recommended monthly parent contribution for a daycare spot in 1999 (around 65 EUR at 2018 prices or 101 guilders, Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport and Ministry of Education, Culture & Science 2000). The size of the cut was thus moderate, especially for more disadvantaged families and when compared to the costs of accessing important services such as daycare. In previous studies, Barr et al. (2022) have recently highlighted long-run intergenerational effects of a $1300 (1200 EUR) discontinuity in the US Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) during children’s first year of life, equal to 10–20% of annual household incomes among EITC recipients. Compared to previous studies, the Dutch 1994 reform thus imparted a smaller cutback in the short run but a much larger one, even if gradual, in the long run.

2.2 Investments, scale economies, and stress in larger families

Two types of parental inputs might be elastic to child-benefit reform and affect child outcomes: investments (of time and money) and stress. Considering parental investments, the effects of child-benefit programs may depend on two complementary mechanisms in larger families, resource dilution and economies of scale (e.g. Cigno et al. 2004). Having more children may increase the cost of investing in them (Becker and Lewis 1973), and parental time and monetary investments may thus dilute when spread over more children (Blake 1981). As such, firstborns can take advantage of more intensive and high-quality parental investments, whilst investments might wane, together with their returns, for subsequent children (e.g. Black et al. 2005; Price 2008; De Haan 2010; for the Netherlands, Cabus and Ariës 2017). The expansion of income-support policies can counter resource dilution by enhancing parental investments (Gibbs et al. 2016). By contrast, cutbacks might limit purchases of (new) goods and services for a larger number of children, especially when household budgets are already stretched in less well-off families.

In equilibrium, parents may increase labour supply and replenish monetary investments with extra earnings (Heckman and Mosso 2014). Yet, working long or inflexible job schedules—disproportionately available to parents in low-paid jobs—might be detrimental to the quality and quantity of parental time inputs (Hsin and Felfe 2014). Parents may further adjust by having fewer children than what would have happened in the absence of cuts (Becker and Lewis 1973), although the evidence is mixed in this regard (Amuedo-Dorantes et al. 2016; González and Trommlerová 2021; Reader et al. 2022). In sum, cutbacks such as the 1994 Dutch reform might exacerbate resource dilution, particularly for less well-off households. However, much depends on if and how families adjust to cutbacks via household labour supply and fertility responses.

Economies of scale, on the other hand, may lead to a decrease in the fixed cost of children. Parents might transmit goods and services from one child to the next, and investments in one child might be productive for the others due to spillovers across siblings (Nicoletti and Rabe 2019; Black et al. 2021). Cutbacks may increase reliance on such economies of scale, with ambiguous effects depending on the reform’s bite. Cutbacks could spur more efficient investments through economies of scale (Cigno et al. 2004). Yet, economies of scale might be hard to implement if cutbacks affect investments that can hardly be passed from one child to the next. Further, economies of scale may yield lower returns in terms of child outcomes in families with little slack in their budgets as compared to families who can afford higher initial investments.

In addition to parental investments, child benefits may ease stress in the household. Children might be adversely affected by the psychological distress that comes with the experience of poverty (e.g. McLoyd 1990; Conger and Donnellan 2007). Both a financial and a psychological stressor, poverty may negatively impact parental mental health and disrupt relationships within the household. A wealth of evidence in developmental psychology (and, increasingly, economics, Duncan et al. 2017; Cobb-Clark et al. 2019) suggests that financial distress may be associated with conflicts between partners and between parents and children. Studies have further linked relationship problems to disparities in socio-emotional skill development and, thereby, worse school attainment (e.g. McLoyd 1990; Duncan et al. 2017; Cooper and Stewart 2021). Even if allotted more income support, larger families typically face relatively higher poverty risks and could thus suffer heightened stress responses to income losses such as those brought by cutbacks. The 1994 Dutch reform might have pushed more families (with lower socio-economic standing) below the poverty line and affected children via the stress channel.

In sum, the effects of cutbacks in families with two or more children hinge upon the combination and relative strength of resource dilution, economies of scale, and stress-related mechanisms. On balance, cutbacks might be detrimental to child outcomes via their consequences on parental inputs, disproportionately so in less well-off families.

3 Data

I use data from the System of Social Statistical Datasets (SSD) of Statistics Netherlands (Bakker et al. 2014). Data come from various population-wide registers that can be merged thanks to a unique personal identifier. The study population was first identified based on the 2021 Basic Register of Persons (BRP). I selected the records of second-born and higher-order children born between October 1994 and March 1995, a 3-month window at each side of the birth cutoff instituted by the reform. Information on the precise date of birth was added to the basic register to identify exposure to the reform. The population is further restricted to those who attended secondary school in the Netherlands and were born to single- and two-parent families. The study population thus comprises 46,080 individuals. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on socio-demographic composition. Besides primarily consisting of second-born children, the study population has no peculiar or selective characteristics compared to other cohorts of children born in the same period (e.g. Oosterbeek et al. 2021).

I examine child outcomes in the pre- and post-reform population in the education and health domain. Data from the Ministry of Education contains information on year-by-year educational enrolment and completed education. In line with previous studies for the Netherlands (Oosterbeek et al. 2021), I examine the school track children are enrolled in by the third year of secondary school. In the Netherlands, only two tracks (HAVO and VWO) give direct access to college and university, respectively. Besides, early tracking has a large impact on future wages (Borghans et al. 2019, 2020). Children in the vocational track (VMBO) can only enter college after completing post-secondary vocational education or by obtaining a HAVO diploma on top of their vocational one. To enrol in university, VMBO students either need to acquire a VWO diploma or complete a college cycle. Only a small fraction of students move ‘upstream’ in the system after the first 2 years of secondary school or after obtaining a vocational diploma (Borghans et al. 2020; Oosterbeek et al. 2021). I thus examine whether children attend the general (HAVO) and the academic track (VWO) which prepare for higher education in the Netherlands.

As for tertiary education,Footnote 7 I evaluate college (HBO) and university degree (WO) completion by 2020–2021 (when children are around 26 years old) to grasp the downstream effects of the reform towards the end of children’s educational trajectories. Colleges or universities of applied sciences typically provide 4-year programmes in higher vocational education geared towards jobs in trade and industry, education, healthcare, and social services, among others. Universities provide 3-year Bachelor programmes and 1- or 2-year Master’s with an academic orientation. The Dutch labour market features a tight match between educational qualifications and job titles (e.g. Di Stasio and Van deWerfhorst 2016), with college degrees leading to career paths in relatively lower-paid occupations. According to the most recent estimates of Statistics Netherlands,Footnote 8 the average hourly wage rate 5 years after graduation is around 20% higher for university degree holders compared to their counterparts with a college degree (see also Allen and Belfi 2020).

Alongside educational outcomes, I focus on mental health as an additional dimension of human capital (Currie 2020) and in light of its cross-productivity with educational attainment (Currie 2009). I analyse access to mental healthcare at both the extensive margin, i.e. any contact with mental healthcare providers, and at the intensive margin, i.e. any stay of 1 day or more in institutional care. I also consider diagnoses that have been widely linked to socio-economic disadvantage and income-support policies in previous studies,Footnote 9 namely depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Different from previous studies on benefit changes that have relied on survey reports (Milligan and Stabile 2011; Hoynes et al. 2016), I use administrative records of diagnoses by mental healthcare providers. For both diagnoses, coding is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).

4 Empirical approach

4.1 Identification

Children are exposed to different child-benefit schemes as a deterministic function of their date of birth. The cutoff separating the two benefit schemes is 1 January 1995. I thus implement a sharp regression discontinuity (RD, Imbens and Lemieux 2008; Cattaneo and Titiunik 2022) design. Let \(X_i\) be the running variable denoting children’s birthdate and c the reform cutoff. The average causal effect of the policy change at the discontinuity can be expressed by

where \(Y_i(1)\) is the potential outcome for unit i under exposure to the reform and \(Y_i(0)\) is the potential outcome under non-exposure. Both are evaluated at the cutoff c. Only one of the two potential outcomes is observed for each unit i. Hence, units born close to the cutoff but unexposed to the reform serve as the counterfactual for the exposed group. The estimand \(\tau \) should thus be interpreted as a local average treatment effect (LATE), i.e. valid for individuals born near the cutoff.

To provide a causal interpretation to \(\tau \), assignment to either the pre-1995 or post-1995 system must depend solely on children’s birthdate. Yet, households might have manipulated the treatment assignment mechanism. For example, parents might have been informed about the cutback and might have timed their next child accordingly to take advantage of the more generous scheme (Borra et al. 2019). Such manipulation is unlikely in this context. The reform was first announced in a coalition agreement in August 1994,Footnote 10 with the new ‘Purple’ government formed by centre-left and centre-right parties being sworn in shortly after. Newspaper articles published in the Dutch national pressFootnote 11 started reporting about plans for reform in September 1994. As the reform was passed on 22 December 1994, parents could not have timed conceptions to take advantage of the pre-1995 system.

As for births, the top panel of Fig. 2 plots daily counts for live births in the study population. Peaks and valleys in the graph correspond to weekdays and weekends/holidays, respectively. Aside from this general pattern, there is no clear-cut evidence of bunching around the reform cutoff that might suggest manipulation due to knowledge of the reform. I also performed standard density tests to check more formally for bunching in the running variable around the cutoff. The density test proposed by Cattaneo et al. (2018) is graphically displayed at the bottom of Fig. 2. The test rejects the presence of bunching (p \(=\).144). If anything, the decline in births before the start of 1995 runs counter to the idea that families had prior knowledge of the policy and timed births to take advantage of the more generous pre-1995 scheme. Rather, a decline in births before the end of 1994 conforms to a general pattern observed across different cohorts and contexts (for the Netherlands, see Oosterbeek et al. 2021).

Further tests can ensure that families on each side of the cutoff are not systematically different. Table 2 presents checks for this ‘continuity’ assumption over a set of covariates—sex of the child as recorded at birth, twin birth, birth order, maternal age (in months), lower socio-economic background (SES, i.e. no parent with postsecondary education), and whether the household is headed by a single parent (as measured at the first available data point, i.e. October 1994). There is no evidence of differences in covariates that might suggest selection around the cutoff.Footnote 12 In addition, I also tested whether pre-determined covariates predict treatment assignment when jointly included in a linear regression model. The F-test does not reject the null, suggesting no evidence of an association between covariates and treatment assignment (p \(=\).310).

Finally, I can rule out other discontinuities at the reform cutoff. No other family policy has been tailored to second-born or subsequent children born on or around 1 January 1995 (for a comprehensive review, Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport and Ministry of Education, Culture & Science 2000). Other changes to child benefits mainly affected its uprating to inflation and applied to all recipients regardless of children’s birthdate. On the other hand, children’s birth month may determine when they can start primary school in the Netherlands, influencing their educational attainment. However, the relevant discontinuity is in October. In contrast, children born between October and March, and especially in the neighbourhood of the January cutoff, start school at the same age on average (Oosterbeek et al. 2021). Evidence and institutional knowledge thus suggest that the 1994 reform can serve as a valid policy discontinuity for the generosity of income support to families with two or more children.

I will present separate results for less well-off households to complement estimates for the whole population. In line with previous literature and with the expectations introduced at the beginning of this paper, reform effects might be stronger for children and parents in households with lower socioeconomic status (SES). I define the latter as households where no parent has postsecondary education (around 73% of the total population,Footnote 13 Table 1). Figure 2A and Table 2A in the Appendix support the continuity assumptions for this sub-population.

I use parental education as a proxy for permanent income in the absence of income measures going back to the 1990 s in the Dutch registers (cf., e.g. Tamborini et al. 2015; Brady et al. 2018). Parental education measures are also more widely available in the other (survey) data sources used in this paper. I will also examine the sensitivity of my results to alternative definitions based exclusively on paternal or maternal education. In addition, I will also rely on measures based on parental earnings rank. Earnings data are the first income measures available in the Dutch registers, dating back to 1999. To minimise concerns over the endogeneity of earnings to the reform, I will focus on the rank of average paternal earnings in the period 1999–2019 (bottom 20%, below the median, below 2/3 of the median). The time series for men’s earnings features fewer gaps due to career interruptions than women’s. Paternal earnings are also unlikely to be as responsive to the reform as maternal earnings (see also Fig. 5A in the Appendix). It is also reasonable to assume that a moderate cutback should not affect paternal earnings rank. The p-values reported at the bottom of Table 3A in the Appendix support the idea that measures of socio-economic status based on paternal earnings rank are not discontinuous at the cutoff.

4.2 Estimation

The estimation of the treatment effect \(\tau \) is based on local linear regressions at each side of the cutoff and robust bias-corrected confidence intervals (Calonico et al. 2014, 2017; Gelman and Imbens 2019). All specifications include pre-determined covariates (Table 1), which may improve precision. Covariates in RD design may also affect the values of the optimal bandwidth and/or the local polynomial fit and thereby result in different standard errors and coefficients. Appendix G.1 shows that key estimates in this study are largely indistinguishable when excluding covariates. Throughout, I constrain covariates’ coefficients to be the same at each side of the cutoff (Calonico et al. 2019).

RD plots for educational outcomes in the study population. Outcomes are averaged within 6-day birthdate bins. Solid black lines display linear predictions following (unadjusted) RD estimation within the optimal bandwidth around the cutoff of 1 January 1995 (see Section 4.2 for details). Dashed lines extend these linear predictions beyond the chosen bandwidth

In line with best practices in the RD literature (for a review, Cattaneo et al. 2019), my preferred specification relies on an optimal bandwidth that minimises the mean squared error (MSE) and is symmetrical around the cutoff. The optimal bandwidth is selected separately for each outcome and ranges from 22 to 31 days around the cutoff. Further, I use a triangular kernel, which assigns monotonically increasing weights to observations close to the cutoff. Using different polynomials, other criteria for bandwidth selection (minimising the coverage error [CER] of the confidence interval), allowing the bandwidth to be asymmetric around the cutoff, adopting different kernel weighting schedules (uniform, Epanechnikov), or implementing a ‘donut-hole’ approach does not alter my main conclusions (see Appendix G.2 and Appendix G.3).

To account for multiple hypotheses across outcomes and sub-populations, I accompany p-values with the ‘sharpened q-values’ proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg (1995). Sharpened q-values control for the false discovery rate, i.e. the expected proportion of rejections that are false positives in a given set. Following previous applications of the procedure (Anderson 2008), I group tests by a) domain (education, health) in the main analyses and b) across sub-populations (alternative definitions of SES) for the same outcome in the sensitivity analyses. Results are sensitive to the correction if q-values lie above conventional rejection thresholds, whilst unadjusted p-values would have suggested rejecting the null instead. For the sake of brevity, I report q-values only for statistically significant estimates that inform my main claims on child outcomes.

5 Children’s long-run outcomes

5.1 Average effects on the study population

Figures 3 and 4 report RD plots for educational and mental health outcomes. Outcomes are averaged within 6-day birthdate bins, whilst solid (dashed) lines are used to display RD predictions within (beyond) the optimal bandwidth around the cutoff. Overall, there is little evidence of discontinuous average outcome levels around the policy cutoff. Children in the reform group appear somewhat less likely to attend the academic track of Dutch secondary school (VWO) at around age 15 and more likely to finish college by age 26 (HBO). As for mental health, average outcomes align closely around the cutoff both in terms of mental healthcare use and mental ill-health diagnoses observed at ages 16 to 20.

RD plots for mental health outcomes in the study population. Outcomes are averaged within 6-day birthdate bins. Solid black lines display linear predictions following (unadjusted) RD estimation within the optimal bandwidth around the cutoff of 1 January 1995 (see Section 4.2 for details). Dashed lines extend these linear predictions beyond the chosen bandwidth

More specifically, estimates at the top of Table 3 suggest that second-born and higher-order children affected by the reform were around 3 percentage points (pp) less likely to attend the academic track in secondary school. The same children were also roughly 3 pp more likely to complete postsecondary education with a college degree. These effects on academic track enrolment and college completion amount to a 12–13% change compared to the respective control-group means, but they do not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (p \(=\).102 and p \(=\).232, respectively). Estimates for enrolment in the general secondary school track (HAVO) and for attaining a university degree are statistically insignificant and trivial. Similarly, estimates for mental health outcomes at the bottom of Table 3 do not provide evidence of reform effects. Contrary to expectations, estimates for depression and ADHD diagnoses are negative (– 0.5 and – 0.4 pp) and sizeable (around 25%) compared to baseline. Paired with the negative estimate on the intensive margin of healthcare utilisation (– 0.3 pp, 30% of baseline), estimates might suggest a lower incidence of severe diagnoses and/or lower access to mental healthcare. Strong conclusions are unwarranted given the large statistical uncertainty surrounding these estimates.

5.2 Children in less well-off households

Reform effects might have been stronger in families with fewer economic resources. Table 4 displays results for children whose parents have not obtained any postsecondary education (for RD plots, see Figs. 3A and 4A in the Appendix).

Estimates for educational outcomes at the top of Table 4 provide more clear-cut evidence of a shift in secondary school track enrolment. Children affected by the reform are around 4 pp less likely to be enrolled in the academic track, VWO (p \(=\).026, albeit q \(=\).118). The effect corresponds to a 16% change compared to the baseline. Given the null and trivial effect on the chances of being enrolled in HAVO, the general track, substitution occurs between VWO and the vocational track (VMBO). In line with estimates for the whole population, I also find a 3 pp higher chance of finishing postsecondary education with a college degree, albeit estimates are more noisy (p \(=\).214). Differently, results for university degree completion are very small and inconclusive. Estimates largely resemble those for the whole population when it comes to mental health outcomes at the bottom of Table 4.

Using different definitions for parental SES yields similar substantive conclusions. Table 3A in the Appendix displays penalties ranging from around 3 pp to around 7 pp (or 17–48% of baseline) for the chance of attending the academic track among children affected by the reform in less well-off households. In general, point estimates are somewhat larger when using earnings-based compared to education-based measures of parental SES, although interval estimates are consistent regardless of the adopted definition. Conclusions are also robust when adjusting for multiple testing (q \(=\).041).

As for postsecondary enrolment, evidence is more conclusive when using earnings-based measures. For example, children born at the right-hand side of the policy cutoff and in the bottom fourth of the paternal earnings distribution are around 7 pp more likely to finish college (p \(=\).035, q \(=\).096). Overall, point estimates indicate a higher likelihood of college completion ranging from around 2 to 9 pp, or 8 to 47% of the baseline. A substitution between college and university is also more apparent when using earnings-based measures. The last three columns of Table 3A suggest that children in low-earning households are around 3 pp (25%) less likely to have completed postsecondary education with a university degree. However, estimates for university-degree completion are not statistically significant at conventional levels nor robust to multiple-testing correction (q \(=\) 1). The substitution between college and university is more clear-cut and robust to multiple-testing corrections when examining older siblings in Appendix D.

For mental health outcomes in Table 4A, the picture is once again inconclusive due to the extent of statistical uncertainty. When focusing on earnings-based measures of parental SES, point estimates indicate a lower likelihood of mental healthcare use at the extensive and intensive margin and lower chances of being diagnosed with ADHD or depression among children affected by the reform. Similar estimates are obtained when examining older siblings in Appendix D.

6 Family adjustments

6.1 Number of children and parental labour supply

Before examining what might explain these patterns, I provide evidence that households did not counter the reform’s cutbacks by scaling back their realised fertility or via extra earnings. RD estimates in Table 6A in the Appendix provide no evidence of adjustments in total fertility on average and in less well-off households. Considering that the baseline value is around three children per household, estimates for the total number of children point to fairly precise null effects.

On the other hand, RD estimates in Fig. 5 show that mothers whose second-born or higher-order child was born on 1 January 1995 or after earn less,Footnote 14 on average, than their counterparts subject to the old child-benefit system. Earnings data are available starting in 1999, meaning that I cannot ascertain effects in the immediate aftermath of the reform. However, earnings penalties experienced by women after the birth of a child are persistent (for the Netherlands, Rabaté and Rellstab 2022): If women affected by the reform altered their labour supply, changes in earnings might thus be visible in the medium and long run. In line with estimates for child outcomes, reform effects on maternal earnings are powered by women in less well-off households. Earning losses for these women reach a maximum of 2,100 EUR in the period (e.g. in 2007, p \(=\).010).

Results in Fig. 5 are not driven by joint labour supply decisions within (different-sex) households, whereby men recoup lost child-benefit income via extra earnings. As shown in Fig. 5A in the Appendix, I do not find evidence of earnings responses among fathers in the population. Rather, I find more evidence of labour supply responses among women in households with lower socioeconomic status exposed to the reform using panel survey data (Sociaal-economisch panel onderzoek, Socio-Economic Panel [SEP] 1984–2002). Due to the relatively small sample size and the lack of data on children’s precise birth dates, I define exposed women as those with two or more children and at least one born in 1995 or after. Those with two or more children born before 1995 belong to the unexposed group. I analyse the outcomes of each group around the birth of their first higher-order child observed during the study period, using women with two or more children but no additional birth during the period as the “pure” control group. Event-study estimates (Sun and Abraham 2021) displayed in Fig. 6A in the Appendix suggest that women with children exposed to the reform experienced larger dips in employment and work hours than women with second-born or higher-order children born before 1995.

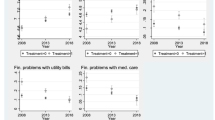

6.2 Investments, exposure to poverty, and stress

Results in the previous section can be rationalised under a model of labour supply dependent on the number of children, childcare costs, and tax-benefit (dis)incentives to work (e.g. Apps et al. 2016). Women with young children can be expected to be more sensitive to changes in work incentives dictated by the tax-benefit system, and more so as the number of children increases (for the NL, Vlasblom et al. 2001; de Boer and Jongen 2023Footnote 15). By reducing income support to larger families, the reform increased the relative cost of daycare compared to childcare at home. Using data from the Budget Survey (1988–2002), Fig. 7A in the Appendix provides suggestive evidence that women with children exposed to the reform were indeed less likely to purchase centre-based care.Footnote 16 Net of differences due to the age of the youngest child, the median investment in daycare was the lowest among households with two or more children and at least one born from 1995 onwards (Fig. 7A, top panel). Further, the bottom-left panel of Fig. 7A suggests that the marginal propensity to consume (MPC, Kooreman 2000) child-benefit money v. that from other income sources on daycare is large and positive for one-child families (49.3% for each additional euro, p \(=\).083), negative for two-child families (\(-\)9.4%, p <.001), and decreases even more for two-child families with at least one post-reform child (–25%, p <.001). Finally, the bottom-right panel displays predicted investments in daycare expressed in terms of months at the minimum recommended fee in the period. Average investments equal to around 15.2 minimum-fee months in one-child families but decline to 9.5 months for larger families where all children were born before 1995 and to around 4.5 months for those with at least one child born in 1995 or after.

Maternal time spent at home rather than in paid work might have compensated for falling investments in daycare among families affected by the reform. Time-diary data from the Dutch sub-sample of the Multinational Time Use Survey (MTUS, Gershuny et al. 2020; see Appendix A for details) further supports this notion, showing that mothers (with lower SES) exposed to the reform spent more time on informal childcare for pre-school children aged 0–4. As per Fig. 8A in the Appendix, per-child time investments among one-child and larger families closely track each other in survey rounds up to 1995. When surveyed in the post-reform period (2000), time investments among larger families are found to be around 24 min (p \(=\).03) higher than the baseline (larger families surveyed in 1995) on an average weekday.

Therefore, educational penalties in the previous sections might stem from households substituting away from centre-based care, which has been found to be most beneficial for skill development among children in less well-off households (e.g. van Huizen and Plantenga 2018). Nevertheless, only around a fifth of children aged 0–3 attended daycare in the period (Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport and Ministry of Education, Culture & Science 2000; Bettendorf et al. 2015), suggesting that substitution between time spent at home and time spent at a childcare centre is not the only mechanism at play here. Additional evidence suggests that other monetary investments in child-related goods might have become less affordable in larger families exposed to the reform. In particular, the top panel of Fig. 9A shows that larger families with at least one child born in 1995 or after lag behind in their expenditures on children’s books, compared to one-child families and those with two or more children born before 1995. As for essentials, expenditures on children’s clothing are similar among larger families exposed and unexposed to the reform. Yet, for both categories of spending, MPCs at the bottom of Fig. 9A follow the same pattern highlighted for daycare expenditures. One-child families devote 3.1% of child-benefit money as opposed to other income to children’s books (p \(=\).011). Two-child families unexposed to the reform follow with a smaller MPC (0.6%, p <.001), whilst the MPC out of child-benefit income for children’s books is nil among families with at least one post-reform child (p \(=\).850). Similarly, one-child families devote to children’s clothing 12.1% of an extra euro of child benefit as compared to other income (p <.001), whilst the same MPC is negative for families with two or more pre-reform children (– 1.2%, p \(=\).015) and even more so among those with at least one child born in 1995 or after (– 4.5%, p \(=\).001). These gradients based on sibship size are coherent with previous research (Kooreman 2000). Families with two or more children appear less likely to earmark child-benefit income for child-related investments, which might point to the presence of scale economies. Lower and negative MPCs for families exposed to the 1994 reform might indicate a stronger reliance on scale economies and/or substitution effects between child-related goods and other expenses.

In fact, households might have shifted their spending patterns as exposure to the reform increased the likelihood of experiencing income poverty. To examine this, I rely again on panel data (SEP 1984–2002) and examine the chances of falling below the relative poverty line—defined as two-thirds of annual equivalised disposable income—with an event-study approach. As displayed in Fig. 10A in the Appendix, I find that poverty risks rise by around 5–6 pp in the first 2 years (p \(=\).010 and p \(=\).023, respectively) after the birth of a second or higher-order child in families with lower socioeconomic standing and children born before the reform. In the following years, however, poverty risks decline for these families. In contrast, poverty risks are higher in the short run (e.g. 10 pp, p \(=\).004 in the first year after the birth of a second or higher-order child) and more persistent among larger families with at least one post-reform child.

Finally, other than re-directing investments in goods and services, poverty exposure might have also been associated with stress among families exposed to the reform. Taking advantage of Dutch administrative data, I examine stress in terms of maternal depression diagnoses (2011–2014), the likelihood that the study child ever lived in a single-parent household (1995–2019), and DSM-IV diagnoses of parent–child relational problemsFootnote 17 (2011–2014), as proxies for strained parental and parent–child relationships. RD estimates in Table 7A provide little evidence of a change in the chances of maternal depression among women with a child affected by the reform. Chances of ever living in a single-parent household are higher among children narrowly exposed to the reform (4 pp, p \(=\).044). However, these estimates seem not to be powered by children in less well-off households as opposed to the bulk of the effects highlighted by previous analyses. Differently, adolescent children were diagnosed with relational problems with their parent(s) around twice as much when exposed to the reform. The effect is driven by less well-off households (p \(=\).034). Note that this diagnosis is hardly prevalent in the study population (baseline rate: 0.5%). Still, reform effects may suggest that relationships within the household may have been destabilised as a result of tight budgets and poverty risks highlighted above (Conger and Donnellan 2007; Duncan et al. 2017).

7 Additional analyses

7.1 Are effects on educational outcomes long-lasting?

Reform effects on less well-off children are more clear-cut for secondary school enrolment than for postsecondary educational attainment. Hence, reform effects might have been short-lived: Children who were less likely to attend one of the tracks preparing for higher education made up for the initial disadvantage by moving ‘upstream’ in the Dutch educational system and attained postsecondary education anyway.

I consider three such moves: (1) from attending the vocational secondary track (VMBO) at around age 15 to ever attaining a general-track diploma (HAVO); (2) from attending the general track (HAVO) to ever obtaining an academic-track diploma (VWO); (3) from attaining a college degree (HBO) to attaining a university degree (WO). Table 8A in the Appendix reports raw transition percentages for such moves among children in households with lower SES exposed and unexposed to the 1994 reform, based on Dutch register data. These values, in line with those observed for cohorts born in the same period (Oosterbeek et al. 2021), only differ by a fraction of a percentage point across the exposed and unexposed. Coherently, RD estimates in Table 9A show little evidence of discontinuities in the chances of moving across branches of the educational system around the policy cutoff.

Absent evidence of such moves, previous findings can be explained in terms of heterogeneous effects. Reform effects observed as early as secondary school are likely driven by those children and households that are most responsive to treatment, i.e. most responsive to variations in family income and the associated parental investments. Being left out of the academic track and not making up for it later as per Table 8A and 9A, these children will never be presented with the choice of attending college/university or notFootnote 18. On the other hand, children who ‘survived’ in the branches of the educational system that prepare for higher education are arguably those less responsive to the reform treatment. It follows that effects on postsecondary attainment are driven by this second group of children and, as a result, might be smaller and noisier than those observed on secondary school track enrolment.

If effects on secondary education are separate from those at later stages of the educational trajectory, there could be long-lasting implications already visible in earnings at labour market entry. Hence, I examine average earningsFootnote 19 in the period between age 21 and the latest available data point (2022) when the study population is around 28. As per Fig. 11A and Table 10A in the Appendix, children in the bottom fourth of the paternal earnings distribution earn roughly 1,615 euros (p \(=\).039) less during their 20 s when narrowly exposed to the 1994 reform. The estimate corresponds to an earnings penalty of around 11.5% relative to baseline or around 5 points in terms of earnings rank (p \(=\).033). These estimates should be considered an upper bound, as point and interval estimates for different sub-populations are consistent yet somewhat noisier. Besides, estimates are not robust to controls for multiple comparisons across sub-populations (q \(=\).27 for average earnings, q \(=\).214 for average earnings rank). Data also cover children’s early 20 s, a period in which full-time education is still common and earnings are more unstable. With these caveats in mind, there is some suggestive evidence that reform effects on children’s educational trajectories might have had long-lasting implications for economic outcomes.

7.2 Placebo check

Finally, I also examine placebo reform effects among ‘fully-treated’ households to strengthen causal claims. Specifically, families whose first child was born around the policy cutoff have all been subject to the new child-benefit system. Replicating my main analysis on this group of firstborns can thus serve as a placebo check, as no discontinuous outcomes around the 1 January 1995 cutoff should be expected in this population. Evidence of discontinuities among firstborns would instead invalidate the evaluation exercise, pointing to other causes of outcome differences for children born in the period beyond child-benefit reform (e.g. differences by birth month or other policies affecting children born in that period regardless of birth order).

Figure 6 compares the estimates obtained for children in the study population (Table 4) to those obtained examining firstborn children born around the policy cutoff (N \(=\) 24,585). Reassuringly, I find little evidence of discontinuities around the cutoff among firstborn children. In particular, point and interval estimates in Fig. 6 markedly differ between the ‘placebo’ and ‘study’ populations when it comes to the chances of secondary school enrolment in the academic track, further buttressing one of the main findings of the study.

8 Discussion and concluding remarks

This paper asks if and why child-benefit payments should vary with sibship size. Relying on a regression discontinuity design, I examine a policy change that curtailed child benefits for families with two or more children in the Netherlands. On average, I cannot detect long-run reform effects on children’s educational or mental-health outcomes. However, children from less well-off families narrowly exposed to the reform are less likely to be enrolled in the academic track of secondary school and more likely to complete postsecondary education with a college diploma rather than a university degree. Estimates are buttressed by sensitivity tests for the definition of SES, the absence of evidence for ‘compensatory’ moves within the educational system, evidence of long-run earnings responses, spillover effects on older siblings, and a placebo check showing null effects for firstborns around the policy cutoff. As for mechanisms, results suggest that, if not for the reform, less well-off children might have benefited from more time in centre-based care, larger investments in child-related goods as opposed to economies of scale, and a less stressful household environment.

Effect sizes are comparable to previous literature on the long-run intergenerational effects of cash support on secondary-school outcomes and adult earnings (e.g. Bastian and Michelmore 2018; Barr et al. 2022). Nonetheless, interval estimates for the same outcomes are compatible with small effects too, and caution should be exercised when comparing them to previous estimates or interpreting reform effects as substantial. Null findings on children’s health outcomes contrast instead with previous research investigating similar policy changes.Footnote 20 For one, a study on child-benefit expansion across Canadian provinces highlighted relatively sizeable improvements in socio-emotional development among pre-teens, based on survey reports by their mothers (Milligan and Stabile 2011). One possibility is that common-method bias affected previous estimates, as those mothers also reported improvements in their own well-being (ibidem). The use of administrative data in this paper should eliminate this source of bias. At the same time, I could not assess changes in well-being that might be economically significant even if not at the margin of clinical diagnoses registered in admin data. In addition, since existing data only covers children from adolescence to early adulthood, I also could not investigate health effects in earlier life and their possible fading out.

Finally, a general limitation of this paper’s RD design is that estimates of causal effects at the cutoff may lack external validity. Various approaches have been recently proposed to assess effects away from the cutoff (for a review, Cattaneo and Titiunik 2022), yet such extrapolations may be invalidated by month-of-birth effects in my application. Besides, more than generalisations to children born in a larger neighbourhood of the cutoff, the relevant policy question in my setting is if estimates may be transportable to different populations (e.g. different cohorts in the Netherlands, children in other countries). It is worth noting then that the composition and baseline outcome levels of children in the study population do not substantially differ from those of other cohorts born in the same decade (Oosterbeek et al. 2021), suggesting wider applicability of my estimates in the Dutch context. At the same time, children in this study grew up amidst a secular increase in parental investments (Gauthier et al. 2004; Dotti Sani and Treas 2016; see also Figs. 7A, 8A, 9A in the Appendix). They were also exposed to two recessions, one during early childhood (early 2000 s) and another around the time of their transition to secondary school (2008/9 recession). These contextual transformations do not pose a threat to identification since they did not differentially apply to children depending on the same birthdate cutoff as the 1994 reform. Yet, results in this study should be read in the context of such transformations: Households affected by the reform might have lost out in the race to increase (monetary) investments in children, whilst becoming more vulnerable to economic downturns. Evidence in this study might thus generalise in the presence of similar trends elsewhere, and effects might even be magnified in settings with less generous safety nets accompanying family-related benefits (e.g. De Nardi et al. 2021; Parolin and Gornick 2021; see also, Van Lancker and Van Mechelen 2015).

With these caveats in mind, this study shows that curtailing income support to families with two or more children can have some economic costs across generations. Most of the effects of cutbacks diluted over time are found to be negligible or null in this study. Yet, in less well-off households, even gradual cuts might still have detrimental effects on parental investments in children and the latter’s life chances. As more countries adopt or reform child benefits (Stewart et al. 2023), evidence in this study may provide a lower-bound estimate of the intergenerational costs of less generous benefit programs and related cutbacks.

Data Availability

This paper uses administrative data from Statistics Netherlands. The System of Social-statistical Datasets (SSD) microdata can be accessed via the following link: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/onze-diensten/customised-services-microdata/microdata-conducting-your-own-research. The SSD microdata was analysed via a secure internet connection (Remote Access) (https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/customised-services-microdata/microdata-conducting-your-own-research/rules-and-sanctioning-policy) after receiving authorization from Statistics Netherlands (CBS). For further details regarding CBS microdata access, please send an email to microdata@cbs.nl. Any errors or omissions are the sole responsibility of the author. Replication codes for this paper can be found at https://osf.io/8mw5s/.

Notes

Source: https://doi.org/10.2908/SPR_EXP_FFA under “Cash benefits (non means-tested)” (last access on 17 April 2024).

Since 2009, families with young children may also qualify for Child Budget (Kindgebonden Budget). Eligibility rules for this second scheme are based on a means test and do not overlap with the discontinuity instituted by the 1994 reform.

See, e.g. official figures from Statistics Netherlands here (https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/37789ksz/table) and here (https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/71487NED/table).

See, e.g. the coalition agreement https://www.parlement.com/9291000/d/tk23715_11h.pdf (last accessed on 20 May 2022).

In 1996, the Dutch government amended the law to smooth differences in benefit rates across families. Specifically, families with a new child born between October and December 1994 have received benefit rates varying by children’s age and sibship size, yet amounts from children’s 6th birthday onwards have been less generous when compared to the rates granted to families with children born before October 1994. I do not examine this policy discontinuity as it overlaps with the Dutch school-starting-age rule (Oosterbeek et al. 2021), as discussed in Section 4.1.

Administrative data on child-benefit amounts have only been collected from 2011 onwards.

Around 41% of the study population has attained tertiary education by age 26. Another 23% has an MBO-4 qualification, the highest level of upper-secondary vocational education. In additional analyses, I have not found evidence of diverging chances of attaining an MBO-4 qualification at each side of the cutoff, either on average or among children from less well-off households.

See https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83815NED/table?ts=1697183999402 and https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83832NED/table?ts=1697183958686 (last access on 13 October 2023).

Causal estimates for the link between (parental) income and depression diagnoses abound in the literature (for a review, Ridley et al. 2020). As for ADHD, genetic transmission from parents to offspring is well established, but the role of environmental factors is not (e.g. **ault et al. 2022). However, studies on child benefits have singled out policy effects on mother-reported behavioural and socio-emotional difficulties (e.g. hyperactivity, see Milligan and Stabile 2011), which could lead to an ADHD diagnosis when exceeding clinical cutoffs (e.g. Goodman et al. 2010). Misdiagnoses are also common with ADHD, as children are evaluated against their peers in the classroom and may compare unfavourably for reasons unrelated to the condition (e.g. their age relative to peers, see Evans et al. 2010; Krabbe et al. 2014; Schwandt and Wuppermann 2016). The rationale for including ADHD in this study, hence, is that curtailing child benefits may have increased marginal (mis)diagnoses of ADHD to the extent that children’s behavioural and socio-emotional difficulties were heightened among those exposed to the reform and/or compared unfavourably to those of their unexposed peers.

For more details, see https://www.parlement.com/id/vh8lnhronvvu/kabinet_kok_i_1994_1998 (last accessed on 17 November 2022). Many parties campaigned for budget cuts before the general elections held in May 1994. Some of the major parties (VVD, D66) proposed cutting child benefit for large families (https://resolver.kb.nl/resolve?urn=ABCDDD:010866713:mpeg21:a0163). Given that coalitions and government programmes are typically defined after the elections, though, it is unlikely that parents had prior knowledge about the specifics of future policy changes at the beginning of 1994.

See, e.g. https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/cda-buit-kinderbijslag-niet-uit~b41385a2/ (last accessed on 17 November 2022).

To account for spurious conclusions when investigating continuity over multiple covariates, I performed the permutation-based test proposed by Canay and Kamat (2018). The null of continuity in pre-determined covariates cannot be rejected in my setting (p \(=\).448)

It is worth noting that coverage of the education register is only partial for older cohorts. However, information on postsecondary attainment is complete for individuals born in the late 1960 s and even more so in the following decades, i.e. the bulk of parents in the study population. The proportion of parents with(out) postsecondary education in our study is largely in line with estimates for the same birth cohorts in previous studies (Tieben and Wolbers 2010), lending credibility to the chosen operationalisation.

Earnings are examined in levels. Results are robust to transformations that minimise the influence of outliers such as taking the inverse hyperbolic sine of earnings (and regardless of the unit of measurement, e.g. Aihounton and Henningsen 2021).

Dutch income taxes in the 1990 s also disincentivised employment among secondary earners in lower-income households (Vlasblom et al. 2001; Bosch and Van der Klaauw 2012). It follows that reductions in labour supply might have been more pronounced among women in less well-off households, which is in line with my results (Fig. 5). The moderate additional dip in labour supply for mothers affected by the reform might have then resulted in lower earnings in the medium run (for example, due to the ‘scarring’ effects of part-time work, Russo and Hassink 2008).

Estimates obtained from the Budget Survey refer to all households and not just to women with lower SES due to the large number of missing values for respondents’ level of education.

According to the DSM-IV, the label of parent–child relational problems ‘should be used when the focus of clinical attention is a pattern of interaction between parent and child (e.g. impaired communication, overprotection, inadequate discipline) that is associated with clinically significant impairment in individual or family functioning or the development of clinically significant symptoms in parent or child’ (see Wamboldt et al. 2015 for further details).

More formally, all children attending, say, the academic track (VWO) have the full set of potential outcomes, i.e. ‘going to college/university’ or ‘not going to college/university’ if exposed to the reform, and ‘going to college/university’ or ‘not going to college/university’ if unexposed. Differently, the vast majority of children attending the vocational track of secondary school (VMBO) only have two potential outcomes, namely ‘not going to university/college’ if exposed and ‘not going to university/college’ if unexposed to the reform. The other two potential outcomes are undefined for this sub-population due to the de facto strict nature of the tracking system in the Netherlands. Slough (2023) has shown that treatment effects on later outcomes in such an outcome sequence (i.e. secondary school track \(\rightarrow \) postsecondary education) might be unidentified when treatment is assigned at the beginning of the sequence (e.g. before tracking) and variation in later outcomes is only observable for some units, based on their earlier outcomes (e.g. can only go or not to university having obtained a diploma from the academic track). One possible solution is to collapse outcome sequences into a single outcome, e.g. ‘attending VWO and attaining university’ in my setting. Results are substantively similar when following this strategy.

I trim average earnings by drop** the top percentile to minimise the influence of (implausibly large) outliers. Estimates are robust to the inclusion of outliers nonetheless.

Other research has found nil effects of financial shocks on children’s health outcomes. For example, examining lottery wins in Sweden, Cesarini et al. (2016) have found little effects on prescription drug consumption among children, including for ADHD. Nonetheless, estimates based on policy changes remain hardly comparable to those exploiting other shocks to household finances due to the different underlying populations (with those skewing towards higher-income households less likely to be responsive to income shocks; see also, e.g. Løken et al. 2012) or the fact that, due to labelling effects (e.g. Kooreman 2000), family-related benefit payments might influence investments in children more than other sources of income/wealth (see also Barr et al. 2022 for a discussion).

References

Aihounton GB, Henningsen A (2021) Units of measurement and the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation. Economet J 24(2):334–351

Allen J, Belfi B (2020) Educational expansion in the Netherlands: better chances for all? Oxf Rev Educ 46(1):44–62

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Averett SL, Bansak CA (2016) Welfare reform and immigrant fertility. J Popul Econ 29(3):757–779

Anderson ML (2008) Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: a reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects. J Am Stat Assoc, 1481–1495

Apps P, Kabátek J, Rees R, van Soest A (2016) Labor supply heterogeneity and demand for child care of mothers with young children. Empir Econ 51(4):1641–1677

Baker M, Messacar D, Stabile M (2023) The effects of child tax benefits on poverty and labor supply: evidence from the Canada Child Benefit and Universal Child Care Benefit. J Law Econ 41(4):1129–1182

Bakker BF, Van Rooijen J, Van Toor L (2014) The system of social statistical datasets of statistics Netherlands: an integral approach to the production of register-based social statistics. Stat J IAOS 30(4):411–424

Barr A, Eggleston J, Smith AA (2022) Investing in infants: the lasting effects of cash transfers to new families. Q J Econ 137(4):2539–2583

Bastian J, Michelmore K (2018) The long-term impact of the earned income tax credit on children’s education and employment outcomes. J Labor Econ 36(4):1127–1163

Becker GS, Lewis HG (1973) On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Pol Econ 81(2, Part 2):S279–S288

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol) 57(1):289–300

Bettendorf LJ, Jongen EL, Muller P (2015) Childcare subsidies and labour supply—evidence from a large Dutch reform. Labour Econ 36:112–123

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG (2005) The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Q J Econ 120(2):669–700

Black SE, Breining S, Figlio DN, Guryan J, Karbownik K, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M (2021) Sibling spillovers. Econ J 131(633):101–128

Blake J (1981) Family size and the quality of children. Demography 18(4):421–442

Blanden J, Hansen K, Machin S (2010) The economic cost of growing up poor: estimating the GDP loss associated with child poverty. Fisc Stud 31(3):289–311

Borghans L, Diris R, Smits W, de Vries J (2019) The long-run effects of secondary school track assignment. PLoS ONE 14(10):e0215493

Borghans L, Diris R, Smits W, de Vries J (2020) Should we sort it out later? The effect of tracking age on long-run outcomes. Econ Educ Rev 75:101973

Borra C, González L, Sevilla A (2019) The impact of scheduling birth early on infant health. J Eur Econ Assoc 17(1):30–78

Bosch N, Van der Klaauw B (2012) Analyzing female labor supply — evidence from a Dutch tax reform. Labour Econ 19(3):271–280

Boyd-Swan C, Herbst CM, Ifcher J, Zarghamee H (2016) The earned income tax credit, mental health, and happiness. J Econ Behav Organ 126:18–38

Bradshaw J, Finch N (2002) A comparison of child benefit packages in 22 countries. Department for work and pensions research report No. 174. Leeds: Corporate Document Services

Brady D, Giesselmann M, Kohler U, Radenacker A (2018) How to measure and proxy permanent income: evidence from Germany and the US. J Econ Inequal 16:321–345

Cabus SJ, Ariës RJ (2017) What do parents teach their children? The effects of parental involvement on student performance in Dutch compulsory education. Educ Rev 69(3):285–302

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Titiunik R (2014) Robust nonparametric confidence intervals for regression-discontinuity designs. Econometrica 82(6):2295–2326

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Farrell MH, Titiunik R (2017) rdrobust: software for regression-discontinuity designs. Stand Genomic Sci 17(2):372–404

Calonico S, Cattaneo MD, Farrell MH, Titiunik R (2019) Regression discontinuity designs using covariates. Rev Econ Stat 101(3):442–451

Canay IA, Kamat V (2018) Approximate permutation tests and induced order statistics in the regression discontinuity design. Rev Econ Stud 85(3):1577–1608

Carneiro P, García IL, Salvanes KG, Tominey E (2021) Intergenerational mobility and the timing of parental income. J Polit Econ 129(3):757–788

Cattaneo MD, Titiunik R (2022) Regression discontinuity designs. Annu Rev Econ 14:821–851

Cattaneo MD, Jansson M, Ma X (2018) Manipulation testing based on density discontinuity. Stand Genomic Sci 18(1):234–261

Cattaneo MD, Idrobo N, Titiunik R (2019) A practical introduction to regression discontinuity designs: foundations. Cambridge University Press

Cesarini D, Lindqvist E, Östling R, Wallace B (2016) Wealth, health, and child development: evidence from administrative data on Swedish lottery players. Q J Econ 131(2):687–738

Cigno A, Luporini A, Pettini A (2004) Hidden information problems in the design of family allowances. J Popul Econ 17(4):645–655

Cobb-Clark DA, Salamanca N, Zhu A (2019) Parenting style as an investment in human development. J Popul Econ 32(4):1315–1352

Conger RD, Donnellan MB (2007) An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol 58:175–199

Cooper K, Stewart K (2021) Does household income affect children’s outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Child Indic Res 14(3):981–1005

Cremer H, Dellis A, Pestieau P (2003) Family size and optimal income taxation. J Popul Econ 16(1):37–54

Currie J (2009) Healthy, wealthy, and wise: is there a causal relationship between child health and human capital development? J Econ Lit 47(1):87–122

Currie J (2020) Child health as human capital. Health Econ 29(4):452–463

Dahl GB, Lochner L (2012) The impact of family income on child achievement: evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit. Am Econ Rev 102(5):1927–56

de Boer H-W, Jongen EL (2023) Analysing tax-benefit reforms in the Netherlands using structural models and natural experiments. J Popul Econ 36(1):179–209

De Haan M (2010) Birth order, family size and educational attainment. Econ Educ Rev 29(4):576–588

De Nardi M, Fella G, Knoef M, Paz-Pardo G, Van Ooijen R (2021) Family and government insurance: wage, earnings, and income risks in the Netherlands and the US. J Public Econ 193:104327

Di Stasio V, Van deWerfhorst HG (2016) Why does education matter to employers in different institutional contexts? A vignette study in England and the Netherlands. Soc Forces 95(1):77–106

Dotti Sani GM, Treas J (2016) Educational gradients in parents’ child-care time across countries, 1965–2012. J Marriage Fam 78(4):1083–1096

Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E (2017) Moving beyond correlations in assessing the consequences of poverty. Annu Rev Psychol 68:413–434

Evans WN, Morrill MS, Parente ST (2010) Measuring inappropriate medical diagnosis and treatment in survey data: the case of ADHD among school-age children. J Health Econ 29(5):657–673

Fox L, Burns K (2022) The impact of the 2021 expanded child tax credit on child poverty. Census Working Paper Number SEHSD-WP2022-24

Gauthier AH, Smeeding TM, Furstenberg FF Jr (2004) Are parents investing less time in children? Trends in selected industrialized countries. Popul Dev Rev 30(4):647–672

Gelman A, Imbens G (2019) Why high-order polynomials should not be used in regression discontinuity designs. J Bus Econ Stat 37(3):447–456

Gershuny J, Vega-Rapun M, Lamote J (2020) Multinational time use study. UCL IOE, University College London, Centre for Time Use Research

Gibbs BG, Workman J, Downey DB (2016) The (conditional) resource dilution model: state-and community-level modifications. Demography 53(3):723–748

González L, Trommlerová SK (2021) Cash transfers and fertility: How the introduction and cancellation of a child benefit affected births and abortions. J Hum Resour, 0220–10725R2

Goodman A, Lam** DL, Ploubidis GB (2010) When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:1179–1191

Heckman JJ, Mosso S (2014) The economics of human development and social mobility. Annu Rev Econ 6(1):689–733

Hoynes H, Schanzenbach DW, Almond D (2016) Long-run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. American Economic Review 106(4):903–34

Hsin A, Felfe C (2014) When does time matter? Maternal employment, children’s time with parents, and child development. Demography 51(5):1867–1894

Imbens GW, Lemieux T (2008) Regression discontinuity designs: a guide to practice. J Econom 142(2):615–635

Ko W, Moffitt RA (2022) Take-up of social benefits. NBER Working Paper no. 30148

Kooreman P (2000) The labeling effect of a child benefit system. Am Econ Rev 90(3):571–583

Krabbe E, Thoutenhoofd E, Conradi M, Pijl S, Batstra L (2014) Birth month as predictor of ADHD medication use in Dutch school classes. Eur J Spec Needs Educ 29(4):571–578

Løken KV, Mogstad M, Wiswall M (2012) What linear estimators miss: the effects of family income on child outcomes. Am Econ J Appl Econ 4(2):1–35

Mayer SE (1997) What money can’t buy: family income and children’s life chances. Harvard University Press

McLoyd VC (1990) The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev 61(2):311–346

Milligan K (2005) Subsidizing the stork: new evidence on tax incentives and fertility. Rev Econ Stat 87(3):539–555

Milligan K, Stabile M (2011) Do child tax benefits affect the well-being of children? Evidence from Canadian child benefit expansions. Am Econ J Econ Pol 3(3):175–205

Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport and Ministry of Education, Culture & Science (2000) Early childhood education and care policy in the Netherlands: background report to the OECD-project ‘Thematic Review of Early Childhood Education and Care Policy’. The Hague, Netherlands: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (Ministry of Health, Welfare & Sport)

Nicoletti C, Rabe B (2019) Sibling spillover effects in school achievement. J Appl Economet 34(4):482–501

Oosterbeek H, ter Meulen S, van Der Klaauw B (2021) Long-term effects of school-starting-age rules. Econ Educ Rev 84:102–144

Parolin ZJ, Gornick JC (2021) Pathways toward inclusive income growth: a comparative decomposition of national growth profiles. Am Sociol Rev 86(6):1131–1163

**ault J-B, Barkhuizen W, Wang B, Hannigan LJ, Eilertsen EM, Corfield E, . . . others (2022) Genetic nurture versus genetic transmission of risk for ADHD traits in the Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study. Molecular Psychiatry

Price J (2008) Parent-child quality time does birth order matter? J Hum Resour 43(1):240–265