Abstract

Introduction

Land use/land cover change can affect the ecological processes of an area such as hydrological cycle. The change in the condition of water resources of an area could be a good indicator of changes in ecosystem function as a result of altered land use/land cover. Eucalyptus expansion in central Ethiopia is one of the recent land use/land cover changes causing controversy on its potential ecological effect. This study was designed to evaluate effects of three adjacent land uses/land covers, i.e. cultivated land, grassland and Eucalyptus woodlot on surface runoff in Meja River watershed, central Ethiopia.

Methods

The rainfall amount at each study catchment was collected using the rain gauge installed to record daily rainfall amount. The three land use/land cover types in each study catchment were selected for comparison as treatments. Four replications of each land use/land cover were used forming a total of 12 runoff plots. The rainfall and runoff data were collected twice a day for 91 days.

Results

The study found that land use/land cover significantly affects surface runoff generated from the plots. Higher runoff was recorded from cultivated land. There was no significant difference on runoff volume between grassland and Eucalyptus woodlot.

Conclusions

This shows that expansion of Eucalyptus on grassland could not have significant impact on surface runoff generation but if planted on previously farmland could reduce surface runoff.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sustainable land management is an important key to the increasing land productivity, better livelihoods and improved ecosystem health (Liniger et al. 2011). Factors that lead to land degradation are population pressure, overgrazing, deforestation, crop cultivation expansion on steep slope and severe soil loss in Ethiopia (Bishaw 2001; Taddese 2001; Tamene and Vlek 2008; Hurni et al. 2010; Gashaw et al. 2014). Land management is about exploring existing and possible land use/land cover (LULC) and making decision on choosing to implement the one that ensure sustainable production (UNEP 2014). Such decisions could directly affect ecosystem functions and services and alter condition of ecosystem resources such as soil, water, flora and fauna (Lemenih 2004; Maitima et al. 2009). Decision makers, therefore, need to carefully weigh the trade-off between increasing productivity on the one hand and loss of other ecosystem functions and services on the other.

In Ethiopia, land degradation had begun with the emergence of cultivation thousand years ago (Hurni 1990; Yirdaw 1996). Ethiopia is recognized for its land resource degradation, food insecurity, which has deforestation and forest degradation as its root causes (Bishaw 2001; Hurni 1990; Tamene and Vlek 2008). Various studies have shown changes in LULC, with most of the changes being the expansion of cultivated land, the increment of bare land, decline in forest areas and reduction in grazing land (Dwivedi et al. 2005; Haile et al. 2010; Kidane et al. 2012). The expansion of Eucalyptus woodlots and plantation are also observed in the highlands of Ethiopia (Jenbere et al. 2012; Chanie et al. 2013; Jaleta et al. 2016a). These dynamics in LULC have direct and indirect impact on soil and water resources of the country.

Studies have been done to assess the impact of different LULC changes on runoff and sediment yield in different parts of Ethiopia since late 1970s (Bayabil et al. 2010; Taye et al. 2013; Tebebu et al. 2015). These studies focused on effects of cultivated land, conservation areas or grassland. Results of the studies recorded the highest runoff from cultivated land (Hurni et al. 2005; Descheemaeker et al. 2006; Girmay et al. 2009; Adimassu et al. 2014).

The recent uncontrolled expansion of Eucalyptus could have significant effects on various ecosystem processes (Kebebew and Ayele 2010; Jenbere et al. 2012; Chanie et al. 2013; Tadele and Teketay 2014; Jaleta et al. 2016b). Eucalyptus expansion has been a contentious matter due to its argued ecological effects (Dessie and Erkossa 2011; Tadele and Teketay 2014; Yitaferu et al. 2013; Jaleta et al. 2016a). Various studies have assessed its effects on soil (Jenbere et al. 2012; Chanie et al. 2013; Yitaferu et al. 2013), water efficiency, allelophatic effect (Nigatu and Michelsen 1993; Fikreyesus et al. 2011) and socio-economy (Mekonnen et al. 2007; Adimassu et al. 2010; Kebebew and Ayele 2010). However, there are few studies that assessed its effect on surface runoff. Moreover, runoff-rainfall effects are site specific, due to various local effects such as climate and biophysical characteristics (Critchley et al. 1991; Girmay et al. 2009). Therefore, it is important to understand how Eucalyptus alters surface runoff patterns compared to other land use system so as to make decision on ecosystem management. The objective of this study was to evaluate surface runoff from three LULC in Meja River watershed, Oromia Regional State, central Ethiopia.

Study area

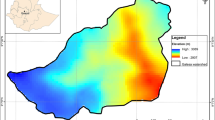

The study was carried out at Meja River watershed, Jeldu District in west Shewa, central Ethiopia. The watershed is located 114 km west of the capital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The watershed is experiencing rapid expansion of Eucalyptus. The altitude of the watershed ranges from 2400 to 3200 m above sea level. The two subcatchments in Meja River watershed called Sochoa and Tiki were selected to carry out the study. The mean annual temperature ranges from 17 to 22 °C. The rainfall is bi-modal with recent fluctuations with the short rainy season from February to May and long rainy season from June to September. The mean annual rainfall is 1400 mm. The agro-ecology of the area belongs to cool highland with sufficient rainfall.

Land use is dominated by a mixed crop-livestock system. Main crops grown in the watershed are barley (Hordium vulgare), wheat (Triticum vulgare) and potato (Solanum tuberosum). The major sources of cash for the community of the area are potato and Eucalyptus products. Average family size is six people, and land holding ranges from 0 to 4 ha. Eucalyptus globulus woodlots are abundant in the study area and established mostly by replacing cultivated land and grazing lands. The soil of the area is Pellic Vertisol.

Methods

Experimental design

The rainfall amount at each study catchment was collected using the rain gauge installed to record daily rainfall amount. The rainfall depth was measured every morning at 6:00 am and in the evening at 6:00 pm. Three LULC types, namely, Eucalyptus woodlot, cultivated land and grassland in each study catchment were selected for comparison as treatments. Four replications of each LULC type were used forming a total of 12 runoff plots. Each runoff plot consisted of an area of 10 m × 4 m with triangular funnelling plot of 4 m × 2.5 m × 2.5 m and cylindrical collecting metal trench of size 0.6 m (depth) × 0.6 m (diameter) (Fig. 2). Thus, the runoff plot has an area of 43.3 m2 (i.e. the entire area of harvesting runoff). External runoff flow into and out flow from the plots were protected by a plastic structure constructed around the plots.

Runoff depth was measured using volume-depth relationships using the water depth of the trench. Measurement was done every morning at 6:00 am and evening at 6:00 pm. Total harvested runoff was collected from the collecting trenches and measured using a graduated cylinder for further check-up of the volume at every morning and evening. The harvested runoff was removed from the collecting trenches. Runoff coefficient was calculated as the ratio of total runoff depth harvested in each plot by total rainfall depth. From each runoff plots, the slope gradient, soil moisture, soil temperature, electric conductivity and ground cover by above-ground biomass were recorded. The data is summarized in Table 1. Slope gradient was measured by clinometer. Soil moisture, soil temperature and electric conductivity were measured at three places along the slope by time domain reflectrometry (TDR) device at the end of the study period, and the average was taken. Stone cover was determined by taking a quadrant of 50 × 50 cm made of wood stick placed at three locations in each plot. Then, the length of the stone surface that comes in contact with ruler which was laid down on five locations was registered, and average was calculated into percentage of the total coverage. The ground cover with stubble, weeds and organic residues was measured in a 1 m × 1 m quadrant laid in three locations. The counting was done following a similar procedure stated above for stone cover. The tree crown cover measurement was done taking the average value of north-south and east-west measurement with tape measure and calculated into percentage (Girmay et al. 2009).

Data analysis

Runoff coefficient was calculated using the following formula:

where RC is the runoff coefficient, ∑ RoF is the total runoff depth harvested in each plot and ∑ RF is the total rainfall depth over the entire rainy season.

The significance of variance of biophysical conditions of the runoff plots, runoff coefficient and runoff volume due to the effect of land use was evaluated using analysis of the significance of variation. Genstat1 15th edition was used to analyse significance of variation. Least significant difference (LSD) test was used to compare mean value at p < 0.05. The correlation analysis was done to observe the relationship of rainfall and runoff volume for each LULC.

Results

The total number of days with rainfall was 75 out of 91 total study days (July–September), which are typical rainy season for the study area. There were two extreme rainfall events registered in this period: one on July 10, 2015 and the other on July 13, 2015. The recorded rainfall amounts were 49 and 48 mm (average of the two rain gauge values), respectively (Fig. 3). The experimental year was a year of overall low rainfall registered in the area, and across the country, it was the most severe drought year registered in 50 years.

There is significant difference at p < 0.05 in soil moisture content among LULC types (Table 1). The moisture content in cultivated land was significantly less than the grassland and Eucalyptus woodlot. The soil electric conductivity of the grassland was significantly different at p < 0.05 with the cultivated land and Eucalyptus woodlot. The soil electric conductivity of the grassland was higher than Eucalyptus woodlot and cultivated land. There is significant difference at p < 0.05 in organic residues coverage among LULC types where Eucalyptus woodlot has significantly higher organic residues over the cultivated land and grassland.

The result indicated that LULC have significant influence on runoff volume and runoff coefficient (percentage) (Table 2). The highest significant mean runoff volume was found on cultivated land (191.9 mm). The lowest runoff volume was recorded from the grassland, but it was not statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) from the runoff volume recorded in Eucalyptus woodlots. The runoff coefficient was in the order of cultivated land > Eucalyptus stand > grassland (Table 2). The runoff coefficient recorded under cultivated land was significantly different with grassland and Eucalyptus (p < 0.05).

The runoff coefficient for the Eucalyptus woodlots and grassland was not significantly different at p < 0.05. The mean runoff generated from each LULC in the study period was 191.9, 147.8 and 154.0 mm (LSD 5.57) for cultivated land, grassland and Eucalyptus stand, respectively. The relative effect of Eucalyptus on runoff was calculated against that of cultivated land by considering cultivated land as 100%. The result indicated that Eucalyptus reduced the runoff generated from cultivated land by 21%. The rainfall and runoff volume have high correlation coefficient in the cultivated land (0.8022), grassland (0.8018) and Eucalyptus (0.8349) as shown in Figs. 4, 5 and 6.

Discussion

Continuous ploughing of land may result in poor soil aggregate and soil crusting that reduces infiltration of rainfall. This is why cultivated land generated high runoff (Girmay et al. 2009). In addition, this study has found less soil moisture content in the cultivated land (Table 1), which directly strengthens the findings of high surface runoff from cultivated land, that means there was less rainfall infiltrate to the soil. Studies, such as Descheemaeker et al. (2006) and Girmay et al. (2009) also reported a similar finding; higher runoff from cultivated land than other land uses. However, Defersha and Melesse (2012) reported lower runoff generated from field with grown-up maize than in grassland and bare land in Kenya, which might be due to the effect of the maize crop. Conversely, Hurni et al. (2005) reported higher runoff on cultivated land than grassland and forest land in the northern highlands of Ethiopia. According to Adimassu et al. (2014), cultivated land with soil bunds generated less runoff than fallow and non-conserved cultivated land in central Ethiopia. The above listed findings could be related to the biophysical conditions of the plots together with the LULC of the plots as this study found. Applying soil and water conservation measures, therefore, reduces runoff generated especially on steep slope (Nyssen et al. 2010; Adimassu et al. 2014; Dagnew et al. 2015).

Our study found that grassland has generated least surface runoff as compared to other land uses. It is due to the dense ground coverage with grass that intercepts raindrops and reduces surface runoff to give it a time for infiltration. The moisture content in grassland was higher than other LULC, which could be one of the reasons for least surface runoff generation from the grassland. Similarly, Hurni et al. (2005) found less runoff coefficient in grassland than degraded area and cultivated land, which was similar also to the study of Girmay et al. (2009). Another study by Bayabil et al. (2010) also found a lower runoff from grassland than cultivated land with maize in Maybar watershed.

On the other hand, Eucalyptus stand generated less surface runoff compared to cultivated land. This is also due to the interception of raindrops by the stand canopy. The ground was also covered by litter fall that reduces speed of runoff and allows relatively better infiltration. This finding conforms to the findings of other studies. For instance, a study by Girmay et al. (2009) reported that in Eucalyptus-dominated plantation with limited understorey vegetation, there was no significant difference in runoff with grassland. Zhou et al. (2002) also stressed that runoff from Eucalyptus plantation decreased with accumulation of litter. However, some other studies reported result contrary to our findings. For instance, Descheemaeker et al. (2006) has found higher runoff under old Eucalyptus plantations (greater than 20 years), which was attributed to limited understorey vegetation cover.

Given the current result and other similar studies, Eucalyptus plantation could be used for catchment protection to reduce surface runoff. Its role can be enhanced with better litter accumulation and managing undergrowth. Canopy interception of Eucalyptus has made runoff generation to be less compared to the cultivated land. The intercepted water loss from Eucalyptus field is lower than other tree plantation and forests (Lima 1993). Tree planting spacing can also influence the amount of runoff generated from the field (FAO 2009). Generally, comparing runoff under Eucalyptus of different places is not advisable as other influencing factors such as soil, slope, precipitation regimes, climate, the growth stage of the forest, the use of ground vegetation and litter by local people often vary (Descheemaeker et al. 2006; FAO 2009). According to Hurni et al. (2005), surface runoff is expected to increase with land use expansion and intensification without soil and water conservation. Similar to this study, Girmay et al. (2009) and Adimassu et al. (2014) have found high correlation coefficient in the rainfall and runoff volume.

Conclusions

LULC can meaningfully influence runoff generation and runoff coefficient. There was significant difference in surface runoff among the compared LULC types. Cultivated land has generated higher surface runoff volume in the study period. However, there was no significant difference between grassland and Eucalyptus woodlots. This could be related with canopy cover, ground cover, litter availability or soil infiltration capacity during study period. According to the finding of this study, shifting the land use from cultivated land to Eucalyptus could reduce 21% of the surface runoff volume generated from the area. Where there is an ample amount of precipitation, using Eucalyptus as soil conservation tree could be one option. This is because it can reduce surface runoff generated from the area as compared to cultivated land.

The main reason for reduced surface runoff in Eucalyptus plantations is believed to be canopy interception that leads storage and slowly movement of water in order to percolate to the ground. As the runoff study spatially limited to the local conditions, further multiple studies should be done. Otherwise, it could not be used to compare the results from different areas. In general, the expansion of Eucalyptus has no significant impact on surface runoff generation if it is expanded on previously grassland. However, it could also significantly reduce the surface runoff generated if it is planted on previously cultivated land. In addition, this study has also observed higher soil moisture under Eucalyptus woodlots than cultivated land. Depending the above observations, Eucalyptus can be used as area conservation tree, especially to reduce soil erosion by water, where high runoff recorded fields with consideration of tree planting spacing. The effect of proper Eucalyptus planting spacing and litter accumulation level on the runoff generation needs further studies in the country.

References

Adimassu Z, Kessler A, Yirga C, Stroosnijder L (2010) Mismatches between farmers and experts on Eucalyptus in Meskan woreda, Ethiopia. In: Gil L, Tadesse W, Tolosana E, Lopez R (Eds.) Proceedings of the conference on Eucalyptus species management, history, status and trends in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 15–17 September 2010. Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research (EIAR), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp 146-159.

Adimassu Z, Mekonnen K, Yirga C, Kessler A (2014) Effect of soil bunds on runoff, soil and nutrient losses, and crop yield in the central highlands of Ethiopia. L Degrad Dev 25:554–564

Bayabil HK, Seifu AT, Amy SC, Tammo SS (2010) Are runoff processes ecologically or topographically driven in the Ethiopian highlands? The case of the Mayabar watershed. Ecohydrology 3:457–466

Bishaw B (2001) Deforestation and land degradation in Ethiopian high lands: a strategy for physical recovery. North East Afr Stud 8(1):7–25

Chanie T, Collick SA, Adgo E, Lehmann CJ, Steenhuis ST (2013) Ecohydrological impacts of Eucalyptus in the semi humid Ethiopian highlands: the Lake Tana Plain. J Hydrol Hydromechanics 61(1):21–29

Critchley W, Siegert K, Chapman C, Finkel M (1991) Water harvesting: a manual for the design and construction of water harvesting schemes for plant production. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, p 154

Dagnew DC, Guzman CD, Zegeye AD, Tibebu TY, Getaneh M, Abate S, Zemale FA, Ayana EK, Tilahun SA, Steenhuis TS (2015) Impact of conservation practices on runoff and soil loss in the sub-humid Ethiopian highlands: the Debre Mawi watershed. J Hydrol Hydromechanics 63(3):210–219

Defersha MB, Melesse AM (2012) Field scale investigation of the effect of land use on sediment yield and runoff using runoff plot data and models in the Mara River basin, Kenya. Catena 89:54–64

Descheemaeker K, Nyssen J, Poesen J, Raes D, Haile M, Muys B, Deckers S (2006) Runoff on slopes with restoring vegetation: a case study from the Tigray highlands, Ethiopia. J Hydrol 331(1–2):219–241

Dessie G, Erkossa T (2011) Eucalyptus in East Africa, socioeconomic and environmental issues. Planted forests and trees. Working paper 46/E, forest management team, forest management division. FAO, Rome, pp 42

Dwivedi RS, Sreenivas K, Ramana KV (2005) Land use/land cover change analysis in part of Ethiopia using Landsat Thematic Mapper data. Int J Remote Sens 26(7):1285–1287

Fikreyesus S, Kebebew Z, Nebiyu A, Zeleke N, Bogale S (2011) Allelopathic effects of Eucalyptus camaldulensis dehnh. on germination and growth of tomato. American-Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci 11(5):600–608

Food and Agriculture Organization (FOA) (2009) Eucalyptus in East Africa. The socio economics and environmental issues. FAO Sub-regional office, eastern Africa, Addis Ababa, pp 46

Gashaw T, Bantider A, Gebre-Silassie H (2014) Land degradation in Ethiopia: causes, impacts and rehabilitation techniques. J Environ Earth Sci 4(9):98–104

Girmay G, Singh BR, Nyssen J, Borrosen T (2009) Runoff and sediment-associated nutrient losses under different land uses in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J Hydrol 376:70–80

Haile G, Assen M, Ebro A (2010) Land use/cover dynamics and its implications since the 1960s in the Borana rangelands of southern Ethiopia. Liv Res Rur Dev 22(7):132

Hurni H (1990) Degradation and conservation of the resources in the Ethiopian highlands. Mou Res Dev 8:123–130

Hurni H, Solomon A, Amare B, Berhanu D, Ludi E, Portner B, Birru Y, Gete Z (2010) Land degradation and sustainable land management in the highlands of Ethiopia. In: Hurni H, Wiesmann U (eds) Global change and sustainable development: a synthesis of regional experiences from research partnerships, vol 5., pp 187–201, Geo Bernensia

Hurni H, Tato K, Zeleke G (2005) The implications of changes in population, land use, and land management for surface runoff in the upper Nile basin area of Ethiopia. Moun Res Dev 25(2):147–154

Jaleta D, Mbilinyi B, Mahoo H, Lemenih M (2016a) Eucalyptus expansion as relieving and provocative tree in Ethiopia. J Agric Ecol Res Int 6(3): 1-12.

Jaleta D, Mbilinyi B, Mahoo H, Lemenih M (2016b) Evaluation of land use/land cover changes and Eucalyptus expansion in Meja watershed, Ethiopia. J Geo Environ Earth Sci Int 7(3): 1-12.

Jenbere D, Lemenih M, Kassa H (2012) Expansion of Eucalypt farm forestry and its determinants in Arsi Negelle District, South Central Ethiopia. Small Sca For 11(3):389–405

Kebebew Z, Ayele G (2010) Profitability and household income contribution of growing Eucalyptus globules (labill.) to smallholder farmers: the case of central highland of Oromia, Ethiopia. European J App Sci 2(1):25–29

Kidane Y, Stahlmann R, Beierkuhnlein C (2012) Vegetation dynamics and land use and land cover change in the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. Environ Monit Ass 184(12):7473–89

Lemenih M (2004) Effects of land use change on soil quality and native flora degradation and restoration in the highlands of Ethiopia: implication for sustainable land management. Swedish University of Agricultural Science, Uppsala, p 70, PhD Dissertation

Lima WP (1993) Impacto ambiental do Eucalipto, 2nd edn. Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, p 26

Liniger HP, Studer RM, Hauert C, Gurtner M (2011) Sustainable land management in practice—guidelines and best practices for sub-Saharan Africa. TerrAfrica, World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT) and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome, p 246

Maitima JM, Mugatha SM, Reid RS, Gachimbi LN, Majule A, Lyaruu H, Pomery D, Mathai S, Mugisha S (2009) The linkages between land use change, land degradation and biodiversity across East Africa. Afri J Environ Sci Techno 3(10):310–325

Mekonnen Z, Kassa H, Lemenih M, Campbell B (2007) The role and management of Eucalyptus in Lode Hetosa district, Central Ethiopia. Forests Trees Livelihoods 17:309–323

Nigatu L, Michelsen A (1993) Allelopathy in agroforestry systems: the effects of leaf extracts of Cupressus lusitanica and three Eucalyptus spp. on four Ethiopian crops. Agrofo Sys 21:63–74

Nyssen J, Clymans W, Descheemaeker K, Poesen J, Vandecasteele I, Vanmaercke M, Zenebe A, Van Camp M, Haile M, Haregeweyn N, Moeyersons J, Martens K, Gebreyohannes T, Deckers J, Walraevens K (2010) Impact of soil and water conservation measures on catchment hydrological response—a case in north Ethiopia. Hydrol Process 24(13):1880–1895

Taddese G (2001) Land degradation: a challenge to Ethiopia. Environ Manag 27(6):815–824

Tadele D, Teketay D (2014) Growth and yield of two grain crops on sites former covered with Eucalypt plantations in Koga watershed, northwestern Ethiopia. J For Res 25(4):935–940

Tamene L, Vlek PLG (2008) Soil erosion studies in northern Ethiopia. In: Braimoh AK, Vlek PLG (Eds.), Land use and soil resources, Springer Science, 7 Business Media, B.V. Dordrecht, pp 73–100

Taye G, Poesen J, Van Wesemael B, Vanmaercke M, Teka D, Deckers J, Goosse T, Maetens W, Nyssen J, Hallet V, Haregeweyn N (2013) Effects of land use, slope gradient and soil and water conservation structures on runoff and soil loss in semi-arid northern Ethiopia. Phy Geo 34(3):236–259

Tebebu TY, Steenhuis TS, Dagnew DC, Guzman CD, Bayabil HK, Zegeye AD, Collick AS, Langan S, MacAliste C, Langendoen EJ, Yitaferu B, Tilahun SA (2015) Improving efficacy of landscape interventions in the (sub) humid Ethiopian highlands by improved understanding of runoff processes. Front Earth Sci 3(49):1–13

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2014) Assessing global land use: balancing consumption with sustainable supply. A report of the working group on land and soils of the international resource panel. United Nations Environment Programme, Paris, pp 132

Yirdaw E (1996) Deforestation and forest plantations in Ethiopia. In: Palo PM, Merry G (eds) Sustainable forestry challenges for develo** countries. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 327–342

Yitaferu B, Abewa A, Amare T (2013) Expansion of Eucalyptus woodlots in the fertile soils of the highlands of Ethiopia: could it be a treat on future cropland use? J Agri Sci 5(8):97–103

Zhou GY, Morris JD, Yan JH, Yu ZY, Peng SL (2002) Hydrological impacts of re-afforestation with eucalyptus and indigenous species: a case study in southern china. For Ecol Manag 167:209–222

Acknowledgements

The first author is funded by the Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) in Sokoine University of Agriculture for his entire PhD study. The International Foundation for Science (IFS) has supported the research work. The authors recognize the support given by the Central Ethiopia Environment and Forestry Research Center in Ethiopia and Sokoine University of Agriculture in Tanzania.

Authors’ contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author DJ designed the study, managed the literature searches and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors BPM, HFM and ML edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jaleta, D., Mbilinyi, B.P., Mahoo, H.F. et al. Effect of Eucalyptus expansion on surface runoff in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Ecol Process 6, 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0071-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-017-0071-y