Abstract

Background

Adefovir dipivoxil is a nucleotide analogue that is approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Adefovir dipivoxil is associated with proximal tubular dysfunction, resulting in Fanconi syndrome, which can cause secondary hypophosphatemic osteomalacia. We describe a case of a patient with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia secondary to Fanconi syndrome induced by adefovir dipivoxil concomitantly with osteoporosis in whom clinical symptoms were improved by adding denosumab (a human monoclonal antibody targeting the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand) to preceding administration of vitamin D3.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old Japanese man had been receiving low-dose adefovir dipivoxil (10 mg/day) to treat chronic hepatitis B for approximately 5 years. He presented to an orthopedic surgeon with severe pain of the right hip and no trauma history, and fracture of the neck of the right femur was identified. In addition, 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphate scintigraphy revealed significantly abnormal uptake in the bilateral ribs, hips, and knees, and he was therefore referred to our university hospital for evaluation of multiple pathological fractures. We diagnosed hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to Fanconi syndrome induced by adefovir dipivoxil therapy. Although we reduced the patient’s adefovir dipivoxil dose and added calcitriol (active vitamin D3), he did not respond and continued to complain of bone pain. Several bone resorption markers and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase were also persistently elevated. Therefore, we added denosumab to vitamin D3 supplementation for treatment of excessive bone resorption. Two months after initiation of denosumab, his hip and knee pain was relieved, along with a decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase and some bone resorption markers.

Conclusions

Although denosumab is not generally an appropriate treatment for acquired Fanconi syndrome, it may be useful for patients who have hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to adefovir dipivoxil-induced Fanconi syndrome associated with excessive bone resorption. However, clinicians should keep in mind that if denosumab is administered to patients with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia accompanied by excessive bone resorption, adequate vitamin D and/or phosphate supplementation should be done before administration of denosumab.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) is an acyclic nucleotide analogue of adenosine monophosphate that is widely used to treat chronic hepatitis B. There is considerable evidence that long-term administration of ADV, even at a low dose, causes renal tubular dysfunction due to nephrotoxicity [1,2,3]. Fanconi syndrome can be induced by generalized proximal tubular dysfunction due to ADV therapy, resulting in hypophosphatemic osteomalacia with pathological fractures [1,2,3].

Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) that is employed for the treatment of osteoporosis [4]. In general, denosumab would not be considered appropriate for patients with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to Fanconi syndrome, because denosumab rapidly inhibits osteoclast-dependent bone and calcium resorption and subsequently induces hypocalcemia. However, we encountered a 60-year-old man with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to ADV-induced Fanconi syndrome in whom clinical manifestations improved after denosumab was added to vitamin D3 supplementation, as reported here.

Case presentation

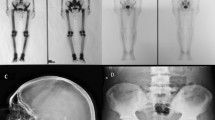

A 60-year-old Japanese man was referred to our hospital for evaluation of severe bone pain and pathological fracture of the neck of the right femur. He had been receiving treatment for chronic hepatitis B with lamivudine (100 mg/day) and ADV (10 mg/day) since December 2006. In June 2013, he noticed low-back pain and then developed severe pain in the right hip. One month later, he also developed pain of the great toe during walking and was referred to an orthopedic surgeon at our hospital. Fracture of the neck of the right femur was found, despite no history of trauma (Fig. 1). In addition, 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphate scintigraphy revealed significantly abnormal uptake in the bilateral ribs, hips, and knees (Fig. 2). In August 2013, he was referred to our outpatient clinic for evaluation of multiple pathological fractures.

On examination, his body mass index was 18.0 kg/m2, temperature was 36.7 °C, blood pressure was 151/86 mmHg, and pulse rate was 67 beats/min (regular). He had generalized bone pain and gait disturbance. His past medical history was appendicitis in 1967 and stomach polyps in 2011. In his family medical history, there was pancreatic cancer, but there was no liver disease. His regular medications were adefovir and ursodeoxycholic acid. He had smoked three packs of cigarettes per day for 30 years, but he had quit since 51 years old. He drinks 350 ml/day of beer. Laboratory tests showed marked elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (1223 U/L), as well as hypophosphatemia (1.9 mg/dl) and mild hypocalcemia (8.5 mg/dl). His serum creatinine was slightly elevated, whereas serum 1α,25(OH)2 vitamin D3 was relatively low at 26.4 pg/ml (reference range, 20.0–60.0 pg/ml) (Table 1).

Urinalysis showed glycosuria (2+) and proteinuria (1+). Urinary β2-microglobulin was markedly elevated at 138,885 μg/g creatinine (Cr), and tubular reabsorption of phosphate was significantly decreased to 41.59% (reference range for percentage tubular reabsorption of phosphate, 80–94%) (Table 1). On the basis of these results, we diagnosed hypophosphatemic osteomalacia secondary to Fanconi syndrome caused by ADV therapy.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry showed an extremely low bone mineral density with a mean lumbar T-score of − 3.6 SD. Several bone resorption markers were highly elevated (urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen, 216.1 nmol bone collagen equivalents/mmol; urinary deoxypyridinoline, 6.7 nmol/mmol Cr; serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b, 781 mU/dl) (Table 1). Taken together, these findings suggested that the patient had excessive bone resorption combined with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia.

To treat his condition, we first reduced the dose of ADV from 10 mg daily to 10 mg every other day and administered calcitriol (1.0 μg/day) because he had both hypophosphatemia and mild hypocalcemia. In October 2013, he underwent prosthetic replacement of the head of the right femur. However, his generalized bone pain was not relieved by these measures, and several bone resorption markers remained very high, as did serum ALP despite treatment for osteomalacia. In June 2016, we added denosumab (60 mg subcutaneously), a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits RANKL, to ongoing vitamin D therapy in an attempt to suppress persistently high bone resorption. Two months after initiation of denosumab, his hip and knee pain were relieved, along with a decrease in serum ALP and several bone resorption markers (Figs. 3 and 4a–c). Urinary β2-microglobulin decreased gradually after addition of denosumab to vitamin D3. After 9 months of denosumab treatment, the patient’s mean lumbar T-score increased from − 2.0 SD to − 1.4 SD (Fig. 4d). We administered denosumab 60 mg every 6 months, and currently he continues to receive denosumab.

Changes in several bone metabolic markers after treatment with denosumab. a Urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen. b Serum tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b. c Urinary deoxypyridinoline. d Bone mineral density of lumbar spine: T-score by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Note: Time lines (x-axes) are different in each of the graphs

Discussion and conclusions

We present a case of a 60-year-old man who had hypophosphatemic osteomalacia secondary to acquired Fanconi syndrome caused by low-dose ADV therapy (10 mg/day). Osteomalacia is a metabolic bone disease characterized by a defective mineralization of the osteoid matrix synthesized by osteoblasts, leading to an accumulation of nonmineralized bone. Osteomalacia is usually associated with vitamin D deficiency or hypophosphatemia. Fanconi syndrome results from generalized dysfunction of the proximal renal tubules, which results in impaired reabsorption of amino acids, glucose, uric acid, bicarbonate, and phosphate, with increased urinary excretion of these solutes [5]. Thus, hypophosphatemic osteomalacia can occur in patients with Fanconi syndrome.

ADV is a nucleotide analogue of adenosine monophosphate that is widely used for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. The mechanisms by which ADV induces nephrotoxicity remain to be determined, but ADV may impair tubular transport, increase apoptosis, or cause mitochondrial injury in the renal tubular epithelium [6]. It has been reported that ADV-related nephrotoxicity is dose-dependent, with a low dose of ADV (10 mg/day) generally being safe and well tolerated [7]. However, there is evidence that even low-dose ADV can induce nephrotoxicity, including Fanconi syndrome, especially in Asian patients [2, 3, 8, 9]. Recently, there has been an increase of reports regarding Fanconi syndrome associated with long-term ADV therapy, even at low doses, in patients from Japan and other Asian countries [8]. In addition, it has been suggested that the incidence of hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to Fanconi syndrome associated with low-dose ADV therapy may be higher than previously thought [9].

In patients with ADV-induced Fanconi syndrome and/or hypophosphatemic osteomalacia, withdrawal or dose reduction of ADV should be performed immediately [5], and oral phosphate, calcium, or vitamin D3 should be added as necessary. In our patient, the dose of ADV was immediately reduced from 10 mg daily to 10 mg every other day. We also initiated treatment with calcitriol (1.0 μg/day) because our patient had hypophosphatemia and slightly low serum calcium and vitamin D3 levels. Generalized renal tubular injury caused by ADV inhibits 1α-hydroxylase activity with subsequent reduction of the 1,25-dihyroxyvitamin D3 level, leading to a decrease in intestinal calcium and phosphate absorption that can contribute to development of osteomalacia [3]. However, generalized bone pain was not relieved in our patient, and several bone resorption markers remained very high, despite ADV dose reduction and vitamin D3 supplementation. The serum level of bone-specific ALP also remained high.

Interestingly, our patient had persistent elevation of bone resorption despite receiving treatment for osteomalacia. Previous studies have shown that bone resorption is occasionally increased in patients with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia because osteoclasts are unable to resorb nonmineralized osteoid [10]. Accordingly, our patient may have a mixed form of osteoporosis and osteomalacia (i.e., osteoporomalacia) [11]. Therefore, we added denosumab (anti-RANKL monoclonal antibody) to vitamin D3 supplementation in order to suppress bone resorption and treat his generalized bone pain. Two months after starting denosumab therapy, the patient’s hip and knee pain showed improvement, together with a decrease in serum bone-specific ALP and bone resorption markers.

Denosumab is a human immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody that inhibits bone resorption by targeting RANKL, which is involved in osteoclast differentiation [4]. Several studies have demonstrated that denosumab is effective for reducing the risk of fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis [12]. Unlike bisphosphonates (another class of potent antiresorptive agents), denosumab does not cause more adverse events in patients with impaired kidney function, because renal insufficiency does not affect its pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics [13]. Thus, we chose denosumab for our patient because he had Fanconi syndrome with generalized proximal tubular dysfunction caused by ADV therapy.

In general, antiresorptive agents such as bisphosphonates and denosumab may not be appropriate for treating hypophosphatemic osteomalacia or other forms of osteomalacia, regardless of the degree of renal insufficiency and vitamin D level. Severe and prolonged hypocalcemia was reported after a single injection of denosumab (60 mg) in a patient with osteomalacia due to Fanconi syndrome [14], because calcium homeostasis is dependent on high bone turnover in osteomalacia. Monitoring of the serum calcium level also is mandatory to prevent severe hypocalcemia when denosumab is initiated in all forms of osteomalacia. Very recently, there was another case report of hypophosphatemia osteomalacia secondary to Fanconi syndrome in which bone pain was worsened by administration of denosumab [15]. Unlike in these reports, we observed that 2 months after initiation of denosumab, hip and knee pain of our patient was relieved along with a decrease in serum ALP and some bone resorption markers. We speculate that denosumab had worked well in our patient because of an adequate administration of vitamin D3 prior to denosumab. We speculate that denosumab may be an option for patients who have hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to ADV-induced Fanconi syndrome with concurrent enhancement of bone resorption and/or osteoporosis. However, clinicians should keep in mind that if denosumab is administered to patients with hypophosphatemic osteomalacia accompanied by persistent excessive bone resorption despite treatment for osteomalacia, adequate vitamin D and/or phosphate supplementation should be done before administration of denosumab.

Abbreviations

- ADV:

-

Adefovir dipivoxil

- AG:

-

Anion gap

- Alb:

-

Albumin

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- BCE:

-

Bone collagen equivalents

- BE:

-

Base excess

- BJ protein:

-

Bence-Jones protein

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CH50:

-

Total hemolytic complement

- ChE:

-

Cholinesterase

- Cre:

-

Creatinine

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FEUA:

-

Fractional excretion of uric acid

- FGF23:

-

Fibroblast growth factor 23

- gGTP:

-

γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- HBe-Ab:

-

Hepatitis B e antigen antibody

- Hbs-Ag:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCO3 − :

-

Bicarbonate

- Hct:

-

Hematocrit

- Ig:

-

Immunoglobulin

- LAP:

-

Leukocyte alkaline phosphatase

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NTx:

-

Cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen

- PCO2 :

-

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- Plt:

-

Platelets

- PO2 :

-

Partial pressure of oxygen

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- PTHrP:

-

Parathyroid hormone-related protein

- RANKL:

-

Receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand

- RBC:

-

Red blood cells

- T-Bil:

-

Total bilirubin

- TP:

-

Total protein

- TRACP-5b:

-

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b

- %TRP:

-

Percentage tubular reabsorption of phosphate

- UA:

-

Urinalysis

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

References

Izzedine H, Launay-Vacher V, Deray G. Antiviral drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(5):804–17.

Wong T, Girgis CM, Ngu MC, Chen RC, Emmett L, et al. Hypophosphatemic osteomalacia after low-dose adefovir dipivoxil therapy for hepatitis B. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):479–80.

Girgis CM, Wong T, Ngu MC, Emmett L, Archer KA, et al. Hypophosphataemic osteomalacia in patients on adefovir dipivoxil. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(5):468–73.

Zaheer S, LeBoff M, Lewiecki EM. Denosumab for the treatment of osteoporosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11(3):461–70.

Hall AM, Bass P, Unwin RJ. Drug-induced renal Fanconi syndrome. QJM. 2014;107:261–9.

Tanji N, Tanji K, Kambham N, Markowitz GS, Bell A, et al. Adefovir nephrotoxicity: possible role of mitochondrial DNA depletion. Hum Pathol. 2001;32(7):734–40.

Izzedine H, Hulot JS, Launay-Vacher V, Marcellini P, Hadziyannis SJ, et al. Adefovir Dipivoxil International 438 Study Group. Renal safety of adefovir dipivoxil in patients with chronic hepatitis B: two double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Kidney Int. 2004;66(3):1153–8.

Eguchi H, Tsuruta M, Tani J, Kuwahara R, Hiromatsu Y. Hypophosphatemic osteomalacia due to drug-induced Fanconi’s syndrome associated with adefovir dipivoxil treatment for hepatitis B. Intern Med. 2014;53(3):233–7.

Wang BF, Wang Y, Wang BY, Sun FR, Zhang D, et al. Osteomalacia and Fanconi’s syndrome caused by long-term low-dose adefovir dipivoxil. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(3):345–8.

Ros I, Alvarez L, Guañabens N, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Hypophosphatemic osteomalacia: a report of five cases and evaluation of bone markers. J Bone Miner Metab. 2005;23(3):266–9.

Bartl R, Bartl C. Drug-induced osteoporomalacia. In: Bone disorders: biology, diagnosis, prevention, therapy. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 441–2.

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, et al. FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(8):756–65. A published erratum appears in N Engl J Med. 2009;361(19):1914

Lipton A, Fizazi K, Stopeck AT, Henry DH, Brown JE, et al. Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: a combined analysis of 3 pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(16):3082–92.

Shafqat H, Alquadan KF, Olszewski AJ. Severe hypocalcemia after densumab in a patient with acquired Fanconi syndrome. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:1187–90.

Chung TL, Chen NC, Chen CL. Severe hypophosphatemia induced by denosumab in a patient with osteomalacia and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-related acquired Fanconi syndrome. Osteoporos Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-018-4679-2.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We did not receive any funding support for the publication of this case report.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK, TI, and YA analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. TJ and MS carried out the clinical treatment and follow-up of the patient. MK and SS collected the data. TK and IU advised on and reviewed this report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

It was not required to submit the case to the institutional ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kunii, T., Iijima, T., Jojima, T. et al. Denosumab improves clinical manifestations of hypophosphatemic osteomalacia by adefovir-induced Fanconi syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 99 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2018-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2018-7