Abstract

Background

Long-lasting reconstruction after extensive resection involving peri-knee metaphysis is a challenging problem in orthopedic oncology. Various reconstruction methods have been proposed, but they are characterized by a high complication rate. The purposes of this study were to (1) assess osseointegration at the bone implant interface and correlated incidence of aseptic loosening; (2) identify complications including infection, endoprosthesis fracture, periprosthetic fracture, leg length discrepancy, and wound healing problem in this case series; and (3) evaluate the short-term function of the patient who received this personalized reconstruction system.

Methods

Between September 2016 and June 2018, our center treated 15 patients with malignancies arising in the femur or tibia shaft using endoprosthesis with a 3D-printed custom-made stem. Osseointegration and aseptic loosening were assessed with digital tomosynthesis. Complications were recorded by reviewing the patients’ records. The function was evaluated with the 1993 version of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS-93) score at a median of 42 (range, 34 to 54) months after reconstruction.

Results

One patient who experienced early aseptic loosening was managed with immobilization and bisphosphonates infusion. All implants were well osseointegrated at the final follow-up examination. There are two periprosthetic fractures intraoperatively. The wire was applied to assist fixation, and the fracture healed at the latest follow-up. Two patients experienced significant leg length discrepancies. The median MSTS-93 score was 26 (range, 23 to 30).

Conclusions

A 3D-printed custom-made ultra-short stem with a porous structure provides acceptable early outcomes in patients who received peri-knee metaphyseal reconstruction. With detailed preoperative design and precise intraoperative techniques, the reasonable initial stability benefits osseointegration to osteoconductive porous titanium, and therefore ensures short- and possibly long-term durability. Personalized adaptive endoprosthesis, careful intraoperative operation, and strict follow-up management enable effective prevention and treatment of complications. The functional results in our series were acceptable thanks to reliable fixation in the bone-endoprosthesis interface and an individualized rehabilitation program. These positive results indicate this device series can be a feasible alternative for critical bone defect reconstruction. Nevertheless, longer follow-up is required to determine whether this technique is superior to other forms of fixation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nowadays, advancing radiography techniques, progressing adjuvant therapies, and precise preoperative simulation enable surgeons to perform challenging limb-salvage surgeries to restore normal joints, especially around the knee [1,2,3,4,5]. These joint-preserving procedures usually result in critical bone stumps with a length ranging from 4 to 10 cm, with which effective fixation is hard to obtain owing to reverse funnel-shaped anatomy, enlarged sectional diameter and reduced anchorage length of the peri-knee metaphysis [6, 7].

Previously, numerous methods including autografts [8,9,10,11], allografts [12,13,14,15], autograft–allograft composite [16,17,18], induced membrane technique [19, 20], distraction osteogenesis [21,22,23] and metallic components [13, 24, 25] have been proposed. Biologic reconstructions can provide bioactive bone tissue once ideal healing is achieved. However, these procedures are time-consuming and accompanied by a high incidence of complications, such as infection, delayed union, nonunion, and fracture [8, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, 26,27,28]. Additionally, the application of biological reconstruction can be limited if either side of the articular surface is involved. Therefore, the intercalary endoprosthesis is favored by some surgeons to substitute the massive bone shaft, because of its advantages including rigid initial stability, adjustable length for diversified bone defects, and relatively rapid restoration of function [29, 30]. Nevertheless, endoprostheses are prone to mechanical complications around the bone implant interface constructs, such as aseptic loosening, endoprosthetic fracture, and periprosthetic fracture [29,30,31,32].

The establishment method of bone implant interface construct, including a compressive osseointegration method, a cemented stem, or an uncemented stem, is crucial for the performance of each intercalary endoprosthesis [13, 24, 33]. The compressive osseointegration method has been documented with reasonable 5-year and 10-year survival by enhancing osseointegration, yet its application in critical bone defects around the knee is rare [34, 35]. The cemented stem contributes to rigid early fixation but lacks osteoconductivity, resulting in widely reported aseptic loosening (range, 0 to 53.8%) [29, 31, 32, 35,36,37,38]. Besides, cross-pin has been introduced to cemented fixation in the peri-knee metaphysis, whereas the strength of bone-stem construct is reduced by the centric pinholes, leading to foreseeable stem fracture [30]. The uncemented stem in the literature, with the ability to facilitate osseointegration, is rarely reported because inadequate bone stock of peri-knee metaphysis can fail to provide sufficient initial stability [6, 32, 39]. Hence, an alternative stem with improved adaptation to the stump, enhanced mechanical strength, reinforced primary stability and predictable osseointegration is expected. With the rapid progress in additive manufacturing techniques, three-dimensional (3D)–printed custom-made endoprosthetic stem with a porous structure provides an option for such ultra-short and dilated medullary cavity.

Our previous study has reported the application of 3D-printed intercalary endoprosthesis in tibial ultra-critical bone defect with a bone stump under 4-cm length [40]. In this study, we designed a series of 3D-printed custom-made ultra-short stems with a porous structure for peri-knee metaphysis with a bone stump ranging from 4- to 10-cm length. We wish to determine, at a minimum of 2 years, the early performance of this new device in the peri-knee metaphysis. The purposes of this study were to (1) assess osseointegration between host bone and 3D-printed custom-made stem with a porous structure and correlated incidence of aseptic loosening; (2) identify complications including infection, endoprosthesis fracture, periprosthetic fracture, and wound healing problem in all patients, and leg length discrepancy in skeletally immature patients; and (3) evaluate the short-term function of the patient who received this personalized reconstruction system.

Methods

Patients

Between September 2016 and June 2018, our center treated 15 patients with malignancies arising in the femur or tibia. The indications were (1) tumors with no evidence of progression clinically or on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies during chemotherapy and (2) following en-bloc resection, the short residual bone stump length ranging from 4 to 10 cm, impossible for standard uncemented stem fixation in our institution. The contraindications were (1) not willing to accept the potential risks of the 3D-printed custom-made endoprosthesis, and (2) the bone stump with a minimum medulla sectional diameter under 9 mm. There were six men and nine women with a median age of 22 years (range, 11 to 61 years) (Table 1).

Diagnoses were osteosarcoma in eight patients, Ewing sarcoma in three, chondrosarcoma in two, parosteal osteosarcoma in one, and metastatic lung cancer in one. The tumor locations were eight femora (four proximal, four diaphyseal) and seven tibia diaphysis. According to the Enneking staging system [41], 14 patients with osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and parosteal osteosarcoma had Stage IIB disease. Among the 11 patients in the study, two cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were administered in eight patients with osteosarcoma (doxorubicin and cisplatin) and three with Ewing sarcoma (vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide/ifosfamide, and etoposide) (Table 1).

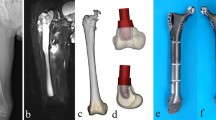

Preoperatively, all patients underwent plain radiography, 3D-computerized tomography (CT), and MRI of their lesions. Single-photon emission CT, chest CT, and biopsy were also performed (Fig. 1A–C).

A The AP radiographic view shows an Ewing sarcoma of the diaphyseal left femur (patient 1). The B CT and C MR images show extension in the surrounding tissues. The virtual D tumor model and E defect model in Mimics software is shown. The F AP view and G lateral view of stem design in distal femoral stump are shown. H The photograph shows the porous structure and whole 3D-printed custom-made stem fabricated with electronic beam melting technique. I The AP radiograph at the latest follow-up is shown

This study was approved by the ethical committee of our institution. Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all patients.

Endoprosthesis design and fabrication

All endoprostheses were designed by our clinical team and fabricated by Chunli Co., Ltd. (Tongzhou, Bei**g, China). 3D-CT and MRI data were integrated by the image fusion technique to build virtual bone and tumor models in Mimics V20.0 software (Materialise Corp., Leuven, Belgium) (Fig. 1D). After confirming the tumor margin, virtual osteotomy was undertaken with an individualized tumor-free bone resection margin (Fig. 1E). The cross-sectional diameters of the maximum inscribed circle at the osteotomy point were measured to assess whether a custom-made stem was required. If so, on the cross-sectional plane, a maximum-inscribed ellipse whose long axis was parallel to the coronal plane was then set and measured as design data of the stem base. To determine the stem length, the depth of the medullary cavity of the stump was measured from the osteotomy point to the endpoint, which varied in skeletally mature and immature patients. In skeletally mature patients, the endpoint was set as the intercondylar notch in the femur and articular surface in the tibia. While in skeletally immature patients, the endpoint was set as the epiphyseal plate. The design of stem length preserved some depth for possibly aseptic loosening, and avoided the interruption to the epiphyseal plate in skeletally immature patients. Before generating the stem according to the size of the previous ellipse and the depth of the preserved stump (Fig. 1F,G), the medullary cavity of the stump was evaluated to determine whether a press-fit fixation can be applied. If a press-fit fixation was accessible, the bone condition would be assessed basically in line with patients’ age. For the patients over 12 years old, their bone condition is usually considered mature enough to enable a press-fit fixation. For the patients under 12 years old, their bone condition including secondary sexual characteristics, height, and body weight would be comprehensively evaluated. Additionally, the first menstruation was an important reference for girl patients. If the bone condition was considered sufficient, a press-fit fixation would be utilized; otherwise, a sub-press-fit fixation using a 1-mm-smaller stem would be applied. After stem tapering, a 2.5-mm-thick porous layer was split to cover the inside solid stem. Cross-pins of 5-mm diameter, with the direction of anteroposterior or transversal, went through the inside solid stem eccentrically to ensure fixation durability. The anteroposterior cross-pins were carefully located if the osteotomy point was near the patellofemoral articular surface in the femur or tuberosity of the tibia. With a porous layer, the contact surface of the stem shoulder matched the outline of the cross-section at the osteotomy point. Meanwhile, two drilling indicators were designed on the extracortical portion of the endoprosthesis stem to guide cross-pin alignment. Thereafter, the following two models were designed to assist implantation. The orientation model had the same stem shoulder and diameter as the endoprosthesis, whereas only 2-mm length of the stem was kept with a sharp edge. The reamer-indicating model had the same stem shoulder and 1-mm thinner stem compared with the real endoprosthesis.

The median length of the resected segment, depth of the preserved medullary cavity, stem, longer and shorter axes of stem section, and length proportion of resected segment to total length were 218.7 mm, 64.4 mm, 51.2 mm, 23.7 mm, 15.8 mm, and 57.4%, respectively. The median number of cross-pins designed in peri-knee metaphysis was 2 (range, 0 to 2) (Table 2).

The endoprosthesis was fabricated with Ti6Al4V alloy using the electron beam melting technique (ARCAM Q10plus, Mol̈ndal, Sweden) (Fig. 1H); meanwhile, the patient-specific instruments and endoprosthesis models were fabricated using the stereolithography appearance technique (UnionTech Lite 450HD, Shanghai, China). The workflow of design, fabrication, and delivery costs about 10 days.

Surgical techniques

All surgeries were performed by the same senior surgeon. Standard techniques for tumor exposure were used, with the principle of obtaining a wide surgical margin. Thereafter, the osteotomy was undertaken precisely with the aid of patient-specific instruments. The orientation model was attached to the host bone tightly to obtain an ellipse mark for the following reaming. The medullary cavity was then reamed with bone files precisely and the trabecular bone was gathered for later autografting. In skeletally immature patients, the medullary cavity was usually un-reamed. After checking the interfacial fitness between the host bone and the orientation model, the trial implantation with the reamer-indicating model was undertaken to ensure whether reaming was adequate or not. The following step was the implantation of the endoprosthesis stem. In skeletally immature patients who were expected to receive a press-fit fixation, the stump was tied using a wire in advance. After the insertion, the stump was fixed with wires before reinserting the stem in all patients who encountered an intraoperative periprosthetic fracture. The cortex was drilled according to the drilling indicators before inserting the cross-pins. Afterward, the reduction of all modular segments (40 to 120 mm, Chunli Co., Ltd., Tongzhou, Bei**g, China) of different lengths was undertaken according to the preoperative plan. At last, the muscles and soft tissue were sutured tightly layer by layer. Meanwhile, in the proximal tibia, rotation of gastrocnemius myocutaneous flap and free skin grafting were performed when necessary to ensure soft tissue coverage [40].

Postoperative management

The rehabilitation protocol was personalized according to tumor location, the length of the resected regimen and preserved host bone, the size of the stem, and the bone condition of the patient. For the patient who received a tibial intercalary endoprosthetic replacement, muscle training was undertaken to reinforce the strength and balance of the lower limb during the first 4 weeks. From 4 weeks postoperatively, standing without weight-bearing was allowed for 2 weeks. Thereafter, patients were encouraged to gradually increase weight-bearing on the affected limb from 10 kg until weight-bearing was equal to that of the contralateral side, and this process usually lasted for 2 weeks. Further, single-leg standing on affected limb and ambulation with walking aids were the next process in the following 4 weeks. Squat training was the last program and usually began 3 months after the surgery.

For the patient who received a femoral intercalary endoprosthetic replacement, the rehabilitation schedule was tighter comparing to former group patients. The muscle training was undertaken in the first 2 weeks after the surgery and followed by a non-weight-bearing stance for 2 weeks. Increasing–weight-bearing stance began at 4 weeks postoperatively and lasted for 2 weeks. Afterward, single-leg stance and ambulation with walking aids for 2 weeks were arranged. At last, squat training was suggested at 2 months postoperatively.

For the patient who received a proximal femoral replacement and hip hemiarthroplasty, the rehabilitation program was similar to patients who received hemipelvic replacement [42]. The total rehabilitation period cost about 3 months.

All patients were evaluated with a physical examination, plain radiography of the femur or tibia before discharge, and once a month during the first 3 months postoperatively and quarterly thereafter (Fig. 1I). Meanwhile, we used digital tomosynthesis (Sonialvision Safire II, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) to assess osseointegration at the bone implant interface (Fig. 2). At a median follow-up interval of 42 months (range, 34 to 54 months), no patient was lost to follow-up, 14 patients had no evidence of disease, and one patient with metastatic lung cancer was alive with disease (Table 1).

The A AP and B lateral plain radiographs show early aseptic loosening in patient 9 3 months postoperatively; The C AP and D lateral digital tomosynthesis graphs show radiolucency and hardened area around the stem. The E AP and F lateral plain radiographs and G AP and H lateral digital tomosynthesis images show well osseointegration at latest follow-up

Primary and secondary study endpoints

Our primary endpoint of interest was osseointegration. Digital tomosynthesis was performed every 3 months postoperatively. Two senior surgeons independently evaluated digital tomosynthesis images at bone implant interfaces. We observed the trabecular structures connected to the implant surface to assess whether there was good osseointegration [43,44,45]. While the aseptic loosening was defined as radiolucency between stem and hardened trabecular bone.

Our second endpoint was complications. Complications including deep infection, wound healing problem, periprosthetic fracture, endoprosthesis fracture, local recurrence, and metastasis were recorded. The leg length discrepancy was measured using a full-length lower limb radiograph at latest follow-up.

Our third endpoint was function. The MSTS-93 score was assessed through a review of patient records undertaken by a surgeon who was not involved in the patient’s care [46]. The MSTS-93 is a limb-specific assessment based on six categories (pain, function, emotional acceptance, supports, walking ability, and gait) specific to the entire lower limb. Each category is scored from 0 to 5, with a total score from 0 to 30 (a higher score is desirable). The MSTS-93 score was administered at the most recent follow-up examination. Meanwhile, the range of motion of the knee joint was measured.

Results

Osseointegration

One patient encountered early aseptic loosening and severe osteoporosis 3 months postoperatively (Fig. 3). The patient’s lower limb was immobilized by plaster, and weight-bearing was forbidden for 1 month, and bisphosphonate was applied thereafter. All implants were well-osseointegrated at the final follow-up examination (Table 1).

Complications

There are two periprosthetic fractures intraoperatively. A wire was applied to assist fixation, and the fracture healed at the latest follow-up. No deep infection, wound healing problem, endoprosthesis fracture, local recurrence, or metastasis was observed during the follow-up (Table 1). The median leg length discrepancy was 1 mm (range, 0 to 13 mm). Among six skeletally immature patients, two patients experienced significant leg length discrepancy of 12 mm (patient 7) and 13 mm (patient 9) (Table 2).

Function

The median MSTS-93 score of all patients was 26 (range, 23 to 30). Specifically, the median MSTS-93 scores of patients who received femoral intercalary endoprosthesis replacement, tibial intercalary endoprosthesis replacement, and proximal femoral endoprosthesis replacement and hip hemiarthroplasty were 27.5 (range, 27 to 30), 26 (range, 23 to 30), and 24.5 (range, 24 to 25), respectively. The median range of motion of the knee joint was 120° (range, 100 to 140°) (Table 1).

Discussion

Endoprostheses provided a viable alternative to biological methods for the massive bone defect in the lower limb because their immediate stability restores reasonable support for early rehabilitation and enables rapid recovery of function [1, 29,30,31,32,33, 36,37,38, 47, 48]. However, in some severe situations with a shortened residual segment, further application of this device is limited due to the incidence of mechanical failures [7, 29, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38, 47,48,49] (Table 3). A novel 3D-printed custom-made stem with a porous structure might minimize the occurrence of mechanical complications. We found satisfactory osseointegration was obtained, and there was a low incidence of complications with acceptable function following the utilization of such a device in this series.

There were several limitations and biases in this study. First, we did not evaluate the oncologic outcome because the small cohort of 15 patients and diverse diagnoses were considered inadequate to assess this outcome. Second, we included both femoral and tibial replacements to obtain a general understanding of this reconstruction method in the lower extremity. The included patients varied in age, height, weight, and treatment protocol. Therefore, one should be careful when introducing our results to individual patients. Third, surgeons’ subjective assessment of osseointegration might result in assessment bias. To mitigate this, the radiography was assessed independently by two surgeons, and clinical outcomes such as pain relief and improved ambulation were also analyzed [42]. Hence, the influence of assessment bias was not severe. Finally, with a short follow-up duration and a small series of 15 patients, the drawbacks might be hindered. Therefore, larger multicenter studies with prolonged follow-up period are needed to evaluate this approach.

All implants were well osseointegrated at the final follow-up examination. Previously, with the wide application of cement in the cemented reconstruction of critical bone defects, the initial stability was relatively easy to secure with the assistance of extracortical plate or cross-pins [29, 30, 33, 36, 38, 47, 48]. While in uncemented fixation, it is challenging to ensure adequate initial stability of the stem in a critical stump due to the absence of cement [1, 32]. Several attempts including spreading stem, hollow stem, and compressive osseointegration fixation have been introduced, while they are limited by the extended length of spreading stem, high aseptic loosening rate of the hollow stem, and common aseptic loosening and endoprosthesis fracture of compressive osseointegration fixation [7, 32, 49]. Additionally, fixation with extracortical plate seems a viable stability booster, whereas it requires adequate cortex exposure which might imperil the attachment of peri-knee non-osseous structures, and therefore impair joint stability and healing process. Hence, the uncemented stem in our series was modified in the following aspects to strengthen both initial stability and osteoconductivity. First, the stem has an ellipse cross-section, utilizing most of the remaining medullary cavity to provide adequate anti-rotation force. Second, the curved stem in the femur and straight stem in tibia sticking to posterior cortex match weight transmission and ensure anti-rotation property. Third, the cross-pins throughout cortex and stem provide extra resistance to rotation and forward or backward leaning. Fourth, before inserting the stem, the medullary cavity was reamed to accommodate the stem model, which was thinner than the real stem for 1 mm. This procedure provides a tight connection to defend the rotation and lean of the stem. Finally, the stem integrated a 2.5-mm-thick porous structure with 600-μm pore size and 60% porosity rather than coating surface, to facilitate osseointegration [51,52,53,54,55]. In our series, one early aseptic loosening occurred in a 13-year-old patient with a stem under 5-cm length. The cross-pin was absent to prevent endoprosthesis fracture, considering thinner stem in his relatively small medullary cavity might be weakened in strength by pinholes. Additionally, a shorter stem was determined because the residual diaphyseal cortex was expected to provide partial press-fit fixation. Intraoperative stability test indicated positive results; nevertheless, stem instability and severe osteoporosis were observed with poor osseointegration at 3 months postoperatively. Thereafter, 1-month immobilization and bisphosphonate were administrated, contributing to final satisfactory osseointegration. Hence, for the stems with a porous structure under 5 cm, osseointegration is expectable with adequate cross-pins, proper immobilization, and probable bisphosphonate [56].

Besides aseptic loosening, endoprosthesis reconstructions involving peri-knee metaphysis are associated with complications including periprosthetic fracture and endoprosthesis fracture [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36, 38, 47, 48, 50]. In our series, two intraoperative periprosthetic fractures occurred. The mild crack fracture might result from the following two reasons. First, owing to the curving design of the stem, implanting the stem requires a larger section when the midpoint of the stem is inserting into the medullary cavity. Additionally, the cortex near metaphysis is thinner than the diaphyseal cortex. After the fixation with wire and cross-pins, the initial stability was considered adequate, and the fracture healed during the follow-up. In the literature, periprosthetic fractures were not uncommon, and the majority of them were caused by trauma [38]. Hence, in our series, although patients obtain good functional outcomes, they are suggested not to undertake vigorous exercise. Besides, comparing to the hollow stem, the blunt-tip-stems in our series behave better in dispersing stress, which benefits preventing further periprosthetic fracture [32]. Moreover, in skeletally immature patients receiving a press-fit fixation, a pre-wire–tied cortex is deemed more tolerant for periprosthetic fracture. To eliminate endoprosthesis fracture, the stem strength was taken into consideration during our design of the stem. Owing to the relatively low mechanical strength of the porous structure, fatigue failure under long-term alternating stress might happen. Therefore, we preserved the inner structure as a solid stem to be covered by a 2.5-mm-thick porous structure layer. Besides, the tunnels for cross-pins were designed as eccentric to the central axis of the stem to avoid occupying the majority of the solid stem which might jeopardize the stem strength. Consequently, no endoprosthesis fracture was observed in our follow-up. Finally, benefitting from the preservation of peri-knee epiphysis, the leg length discrepancy is not severe. The only two patients who encountered leg length discrepancy are considered resulting from the resection of the proximal femoral epiphysis and distal tibial epiphysis.

The median MSTS-93 score of all patients was 26 (range, 23 to 30). Reasonable preservation of the native joints at two ends of the femur or tibia benefits the restoration of lower-limb function [36]. In the literature, the patients with segmental bone defects in the lower extremities received an MSTS score ranging from 22.5 to 28 [29, 31, 35,36,37,38]. However, the majority of these endoprosthetic reconstructions involved diaphysis with the assistance of cement, and satisfactory function was obtained resulting from satisfactory initial stability and following early mobilization. In patients receiving uncemented fixation to a critical stump, to counterbalance early rehabilitation for better function and prolonged immobilization for bone healing is still challenging. In our series, personalized rehabilitation programs were applied, and our patients with intercalary reconstruction received similar functional restoration with a median MSTS score of 27.5 (femur) and 26 (tibia). Meanwhile, the patients received hip hemiarthroplasty, and proximal femoral endoprosthesis replacement obtained acceptable functional outcome with a median MSTS score of 24.5. The result is comparable to the literature with an MSTS score range of 18 to 24 [57,58,59,60,61].

Conclusions

A 3D-printed custom-made ultra-short stem with a porous structure provides acceptable early outcomes in patients who received peri-knee metaphyseal reconstruction. With detailed preoperative design and precise intraoperative techniques, the reasonable initial stability benefits osseointegration to osteoconductive porous titanium, and therefore ensures short- and possibly long-term durability. Personalized adaptive endoprosthesis, careful intraoperative operation, and strict follow-up management enable effective prevention and treatment of complications. The functional results in our series were acceptable thanks to reliable fixation in the bone-endoprosthesis interface and an individualized rehabilitation program. These positive results indicate this device series can be a feasible alternative in critical bone defect reconstruction. Nevertheless, longer follow-up is required to determine whether this technique is superior to other forms of fixation.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- MSTS:

-

Musculoskeletal Tumor Society

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Liu W, Shao Z, Rai S, Hu B, Wu Q, Hu H, et al. Three-dimensional-printed intercalary prosthesis for the reconstruction of large bone defect after joint-preserving tumor resection. J Surg Oncol. 2020;121(3):570–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25826.

Refaat Y, Gunnoe J, Hornicek FJ, Mankin HJ. Comparison of quality of life after amputation or limb salvage. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:298–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200204000-00034.

Rougraff BT, Simon MA, Kneisl JS, Greenberg DB, Mankin HJ. Limb salvage compared with amputation for osteosarcoma of the distal end of the femur. A long-term oncological, functional, and quality-of-life study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(5):649–56. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-199405000-00004.

Aksnes LH, Bauer HC, Jebsen NL, Folleras G, Allert C, Haugen GS, et al. Limb-sparing surgery preserves more function than amputation: a Scandinavian sarcoma group study of 118 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2008;90:786–94.

Fan H, Fu J, Li X, Pei Y, Li X, Pei G, et al. Implantation of customized 3-D printed titanium prosthesis in limb salvage surgery: a case series and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13(1):308. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-015-0723-2.

Panagopoulos GN, Mavrogenis AF, Mauffrey C, Lesensky J, Angelini A, Megaloikonomos PD, et al. Intercalary reconstructions after bone tumor resections: a review of treatments. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2017;27(6):737–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-017-1985-x.

Burger D, Pumberger M, Fuchs B. An uncemented spreading stem for the fixation in the metaphyseal femur: a preliminary report. Sarcoma. 2016;2016:7132838.

Kiss S, Terebessy T, Szoke G, Kiss J, Antal I, Szendroi M. Epiphysis preserving resection of malignant proximal tibial tumours. Int Orthop. 2013;37(1):99–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-012-1731-2.

Ghert M, Colterjohn N, Manfrini M. The use of free vascularized fibular grafts in skeletal reconstruction for bone tumors in children. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(10):577–87. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200710000-00001.

Malizos KN, Zalavras CG, Soucacos PN, Beris AE, Urbaniak JR. Free vascularized fibular grafts for reconstruction of skeletal defects. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12(5):360–9. https://doi.org/10.5435/00124635-200409000-00010.

Xu M, Xu M, Zhang S, Li H, Qiuchi AI, Yu X, et al. Comparative efficacy of intraoperative extracorporeal irradiated and alcohol-inactivated autograft reimplantation for the management of osteosarcomas-a multicentre retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(1):157. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02271-w.

Muscolo DL, Ayerza MA, Aponte-Tinao LA, Ranalletta M. Partial epiphyseal preservation and intercalary allograft reconstruction in high-grade metaphyseal osteosarcoma of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(12):2686–93. https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200412000-00015.

Albergo JI, Gaston LC, Farfalli GL, Laitinen M, Parry M, Ayerza MA, et al. Failure rates and functional results for intercalary femur reconstructions after tumour resection. Musculoskelet Surg. 2020;104(1):59–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-019-00595-1.

Aponte-Tinao L, Farfalli GL, Ritacco LE, Ayerza MA, Muscolo DL. Intercalary femur allografts are an acceptable alternative after tumor resection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):728–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-1952-5.

Aponte-Tinao LA, Ayerza MA, Albergo JI, Farfalli GL. Do massive allograft reconstructions for tumors of the femur and tibia survive 10 or more years after implantation? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(3):517–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000806.

Campanacci DA, Totti F, Puccini S, Beltrami G, Scoccianti G, Delcroix L, et al. Intercalary reconstruction of femur after tumour resection: is a vascularized fibular autograft plus allograft a long-lasting solution? Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B(3):378–86. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.100B3.BJJ-2017-0283.R2.

Friedrich JB, Moran SL, Bishop AT, Wood CM, Shin AY. Free vascularized fibular graft salvage of complications of long-bone allograft after tumor reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(1):93–100. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.G.00551.

Li J, Chen G, Lu Y, Zhu H, Ji C, Wang Z. Factors influencing osseous union following surgical treatment of bone tumors with use of the Capanna technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(22):2036–43. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.19.00380.

Fitoussi F, Ilharreborde B. Is the induced-membrane technique successful for limb reconstruction after resecting large bone tumors in children? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(6):2067–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4164-6.

Masquelet A, Kanakaris NK, Obert L, Stafford P, Giannoudis PV. Bone repair using the Masquelet technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(11):1024–36. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.00842.

Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Minematsu K, Mori Y, Asada N, Kitano S. Limb salvage using distraction osteogenesis. A classification of the technique. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1997;79(3):403–11. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.79B3.0790403.

Tsuchiya H, Abdel-Wanis ME, Sakurakichi K, Yamashiro T, Tomita K. Osteosarcoma around the knee. Intraepiphyseal excision and biological reconstruction with distraction osteogenesis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2002;84(8):1162–6. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.84B8.0841162.

Wang W, Yang J, Wang Y, Han G, Jia JP, Xu M, et al. Bone transport using the Ilizarov method for osteosarcoma patients with tumor resection and neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Bone Oncol. 2019;16:100224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbo.2019.100224.

Ahlmann ER, Menendez LR. Intercalary endoprosthetic reconstruction for diaphyseal bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2006;88:1487–91.

Aldlyami E, Abudu A, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM. Endoprosthetic replacement of diaphyseal bone defects. Long-term results. Int Orthop. 2005;29(1):25–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-004-0614-6.

Campanacci DA, Puccini S, Caff G, Beltrami G, Piccioli A, Innocenti M, et al. Vascularised fibular grafts as a salvage procedure in failed intercalary reconstructions after bone tumour resection of the femur. Injury. 2014;45(2):399–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2013.10.012.

Brunet O, Anract P, Bouabid S, Babinet A, Dumaine V, Tomeno B, et al. Intercalary defects reconstruction of the femur and tibia after primary malignant bone tumour resection. A series of 13 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97(5):512–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2011.03.021.

Gupta S, Kafchinski LA, Gundle KR, Saidi K, Griffin AM, Wunder JS, et al. Intercalary allograft augmented with intramedullary cement and plate fixation is a reliable solution after resection of a diaphyseal tumour. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(7):973–8. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B7.BJJ-2016-0996.

Benevenia J, Kirchner R, Patterson F, Beebe K, Wirtz DC, Rivero S, et al. Outcomes of a modular intercalary endoprosthesis as treatment for segmental defects of the femur, tibia, and humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(2):539–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4588-z.

Bernthal NM, Upfill-Brown A, Burke ZDC, Ishmael CR, Hsiue P, Hori K, et al. Long-term follow-up of custom cross-pin fixation of 56 tumour endoprosthesis stems: a single-institution experience. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(6):724–31. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.101B6.BJJ-2018-0993.R1.

Guder WK, Hardes J, Gosheger G, Nottrott M, Streitburger A. Ultra-short stem anchorage in the proximal tibial epiphysis after intercalary tumor resections: analysis of reconstruction survival in four patients at a mean follow-up of 56 months. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137(4):481–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-017-2637-7.

Streitburger A, Hardes J, Nottrott M, Guder WK. Reconstruction survival of segmental megaendoprostheses: a retrospective analysis of 28 patients treated for intercalary bone defects after musculoskeletal tumor resections. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03583-4.

Lempberg R, Ahlgren O. Prosthetic replacement of tumour-destroyed diaphyseal bone in the lower extremity. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53(4):541–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/17453678208992254.

Goldman LH, Morse LJ, O'Donnell RJ, Wustrack RL. How often does spindle failure occur in compressive osseointegration endoprostheses for oncologic reconstruction? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(7):1714–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4839-7.

Tedesco NS, Van Horn AL, Henshaw RM. Long-term results of intercalary endoprosthetic short segment fixation following extended diaphysectomy. Orthopedics. 2017;40(6):e964–70. https://doi.org/10.3928/01477447-20170918-04.

Hanna SA, Sewell MD, Aston WJ, Pollock RC, Skinner JA, Cannon SR, et al. Femoral diaphyseal endoprosthetic reconstruction after segmental resection of primary bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2010;92:867–74.

Huang HC, Hu YC, Lun DX, Miao J, Wang F, Yang XG, et al. Outcomes of intercalary prosthetic reconstruction for pathological diaphyseal femoral fractures secondary to metastatic tumors. Orthop Surg. 2017;9(2):221–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/os.12327.

Sewell MD, Hanna SA, McGrath A, Aston WJ, Blunn GW, Pollock RC, et al. Intercalary diaphyseal endoprosthetic reconstruction for malignant tibial bone tumours. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2011;93:1111–7.

Lu M, Li Y, Luo Y, Zhang W, Zhou Y, Tu C. Uncemented three-dimensional-printed prosthetic reconstruction for massive bone defects of the proximal tibia. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16(1):47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1333-6.

Zhao D, Tang F, Min L, Lu M, Wang J, Zhang Y, et al. Intercalary reconstruction of the "ultra-critical sized bone defect" by 3D-printed porous prosthesis after resection of tibial malignant tumor. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:2503–12. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S245949.

Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;(153):106-20.

Wang J, Min L, Lu M, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Luo Y, et al. What are the complications of three-dimensionally printed, custom-made, integrative hemipelvic endoprostheses in patients with primary malignancies involving the acetabulum, and what is the function of these patients? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(11):2487–501. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000001297.

Guo S, Tang H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Shao H, Yang D. Accuracy of digital tomosynthesis with metal artifact reduction for detecting osteointegration in cementless hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2018;33(5):1579–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.12.037.

Kim W, Oravec D, Nekkanty S, Yerramshetty J, Sander EA, Divine GW, et al. Digital tomosynthesis (DTS) for quantitative assessment of trabecular microstructure in human vertebral bone. Med Eng Phys. 2015;37(1):109–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.11.005.

Minoda Y, Yoshida T, Sugimoto K, Baba S, Ikebuchi M, Nakamura H. Detection of small periprosthetic bone defects after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast. 2014;29(12):2280–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.013.

Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;(286):241-6.

Hamada K, Naka N, Omori S, Outani H, Oshima K, Joyama S, et al. Intercalary endoprosthesis for salvage of failed intraoperative extracorporeal autogeneous irradiated bone grafting (IORBG) reconstruction. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014(3):rju014. https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju014.

Lun DX, Hu YC, Yang XG, Wang F, Xu ZW. Short-term outcomes of reconstruction subsequent to intercalary resection of femoral diaphyseal metastatic tumor with pathological fracture: comparison between segmental allograft and intercalary prosthesis. Oncol Lett. 2018;15(3):3508–17. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.7804.

Calvert GT, Cummings JE, Bowles AJ, Jones KB, Wurtz LD, Randall RL. A dual-center review of compressive osseointegration for fixation of massive endoprosthetics: 2- to 9-year followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(3):822–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-013-2885-y.

Stevenson JD, Wigley C, Burton H, Ghezelayagh S, Morris G, Evans S, et al. Minimising aseptic loosening in extreme bone resections: custom-made tumour endoprostheses with short medullary stems and extra-cortical plates. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(12):1689–95. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B12.BJJ-2017-0213.R1.

Bose S, Vahabzadeh S, Bandyopadhyay A. Bone tissue engineering using 3D printing. Mater Today. 2013;16(12):496–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2013.11.017.

Taniguchi N, Fujibayashi S, Takemoto M, Sasaki K, Otsuki B, Nakamura T, et al. Effect of pore size on bone ingrowth into porous titanium implants fabricated by additive manufacturing: an in vivo experiment. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016;59:690–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2015.10.069.

Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26(27):5474–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002.

Palmquist A, Snis A, Emanuelsson L, Browne M, Thomsen P. Long-term biocompatibility and osseointegration of electron beam melted, free-form-fabricated solid and porous titanium alloy: experimental studies in sheep. J Biomater Appl. 2013;27(8):1003–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885328211431857.

Hou G, Liu B, Tian Y, Liu Z, Zhou F, Ji H, et al. An innovative strategy to treat large metaphyseal segmental femoral bone defect using customized design and 3D printed micro-porous prosthesis: a prospective clinical study. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2020;31(8):66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10856-020-06406-5.

Vertesich K, Sosa BR, Niu Y, Ji G, Suhardi V, Turajane K, et al. Alendronate enhances osseointegration in a murine implant model. J Orthop Res. 2021;39(4):719-26. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.24853.

Houdek MT, Rose PS, Ferguson PC, Sim FH, Griffin AM, Hevesi M, et al. How often do acetabular erosions occur after bipolar hip endoprostheses in patients with malignant tumors and are erosions associated with outcomes scores? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477(4):777–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000534684.99833.10.

Harvey N, Ahlmann ER, Allison DC, Wang L, Menendez LR. Endoprostheses last longer than intramedullary devices in proximal femur metastases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(3):684–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-011-2038-0.

Calabro T, Van Rooyen R, Piraino I, Pala E, Trovarelli G, Panagopoulos GN, et al. Reconstruction of the proximal femur with a modular resection prosthesis. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26(4):415–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-016-1764-0.

Potter BK, Chow VE, Adams SC, Letson GD, Temple HT. Endoprosthetic proximal femur replacement: metastatic versus primary tumors. Surg Oncol. 2009;18(4):343–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2008.08.007.

Nooh A, Alaseem A, Epure LM, Ricard MA, Goulding K, Turcotte RE. Radiographic, functional, and oncologic outcomes of cemented modular proximal femur replacement using the "French paradox" technique. J Arthroplast. 2020;35(9):2567–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.047.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

The institution of one or more of the authors (Y. Zhou, L. Min, C. Tu) has received, during the study period, funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFB0702604; 2016YFC1102003), 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (ZYJC18036), and Chengdu Science and Technology Project (2017-CY02-00032-GX).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JW, JA, LM, and CT were involved with the concept and design of this manuscript. YL, YZh, JL, and YZ were involved with the acquisition of subjects and data. JW, ML, and CT were involved in the design of the endoprosthesis. LM and CT were involved in the postsurgical evaluation of the patients. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting, and critically revising the paper; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The authors have read and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital and has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards as well as local legislation in research.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., An, J., Lu, M. et al. Is three-dimensional–printed custom-made ultra-short stem with a porous structure an acceptable reconstructive alternative in peri-knee metaphysis for the tumorous bone defect?. World J Surg Onc 19, 235 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02355-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-021-02355-7