Abstract

Nanomaterials (NMs) have received considerable attention in the field of agrochemicals due to their special properties, such as small particle size, surface structure, solubility and chemical composition. The application of NMs and nanotechnology in agrochemicals dramatically overcomes the defects of conventional agrochemicals, including low bioavailability, easy photolysis, and organic solvent pollution, etc. In this review, we describe advances in the application of NMs in chemical pesticides and fertilizers, which are the two earliest and most researched areas of NMs in agrochemicals. Besides, this article concerns with the new applications of NMs in other agrochemicals, such as bio-pesticides, nucleic acid pesticides, plant growth regulators (PGRs), and pheromone. We also discuss challenges and the industrialization trend of NMs in the field of agrochemicals. Constructing nano-agrochemical delivery system via NMs and nanotechnology facilitates the improvement of the stability and dispersion of active ingredients, promotes the precise delivery of agrochemicals, reduces residual pollution and decreases labor cost in different application scenarios, which is potential to maintain the sustainability of agricultural systems and improve food security by increasing the efficacy of agricultural inputs.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particles with nanometers sizes in at least one dimension are commonly known as nanomaterials (NMs) [1, 2]. Due to their small size, NMs are used in many fields, such as life sciences, aerospace, electronics, chemical production, and agriculture. Many inorganic nanoparticles are employed as NMs, for example, carbon nanotubes are usually used as carriers; Iron nanoparticles are widely used due to their magnetism; Silica nanoparticles have attracted research attention for their abundant pore structure and large specific surface area. Other studies have focused on copper, gold, or silver nanoparticles [3]. Polymers and liposomes are renewable, biodegradable, and environmentally friendly, usually used as organic carriers to encapsulate pesticides [4, 5]. These materials are also called nanostructured materials (NSMs) or engineered nanomaterials (ENMs), and most applications are concentrated on efficiency and productivity enhancement.

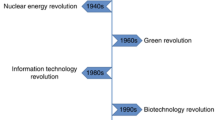

Roco et al. were the first to note that NMs can be used for drug delivery [6]. A National Planning Workshop of America proposed the use of NMs in agriculture, mainly for rapid detection of pesticide residues and food packaging [7]. Subsequent research on the application of NMs has involved various aspects of agrochemicals such as pesticide formulations [8, 9], pesticide residues analysis [10, 11], fertilizers [12, 13], plant growth regulators (PGRs) [14], and development of bio-pesticides [15, 16], including nucleic acid pesticides and pheromone. The application of NMs in agrochemicals is shown in Fig. 1. In 2019, IUPAC selected ten chemical technologies most likely to impact human society in the future [17], and nanopesticides were ranked first for their potential low impact on the environment and human health. Benefits such as increased penetration [18], coverage [19] and uptake of active ingredients (AIs) [20] on the target in the presence of NMs will also occur for all agrochemicals with nanotechnology applications in agriculture [21]. Nano-agrochemical delivery system via NMs have great potential for improving the efficacy of agricultural inputs, alleviating environmental pollution, and saving labor costs, which contributes to the maintenance of the sustainability of agricultural systems and the improvement of food security. NMs will have prospective future in agriculture [22].

Nanomaterials loaded with various agrochemicals. Multiple release modes of active ingredients by modulating the structure of the loading system (Particle, Fiber, Layered system, Porous based, Capsule, Emulsion). The small size effect and large specific surface area of nanoparticles can adhere to the target as much as possible to improve the bioavailability of active ingredients

Although NMs have promising applications in agrochemical delivery [23, 24], academics have also raised some concerns [25], mainly in terms of the unknown health risks for human beings and regulatory difficulties brought by the small size effect of NMs. The complexity and cost of manufacturing technology also limit the large-scale use of NMs in agriculture [26]. In this paper, we illustrate the recent advances and challenges of NMs applied as plant protection agrochemicals.

Nanomaterials for pesticide and fertilizer applications

Pesticides and fertilizers are the most widely used agrochemicals in agricultural production [27], and NMs were the earliest to be applied to these two agrochemicals which are also the most researched and reported. Constructing pesticides and fertilizers delivery system through different strategies could improve their utilization and reduce the run-off to environment, which contributes to alleviating environmental pollution and negative impact on the non-target organism caused by excessive use of agricultural inputs.

Nanomaterials for the establishment of pesticide formulations

Pesticides play a crucial role in defending against biological disasters and promoting crop productivity. Most AIs of pesticides are lipid-soluble [28]. Preparing AIs into liquid formulations requires numerous organic solvents; emulsifiers and other additives are also essential. These requirements can trigger overuse of organic solvents, posing a threat to the environment and human health. Solid formulations need solid emulsifiers and many inert materials as fillers, and they are widely used due to their easy storage and transportation. However, dust pollution is caused in the process of production and application, because of lacking effective protection measures, which is prone to harming non-target organisms as well. Wettable powder (WP) and emulsifiable concentrate (EC) are main pesticide formulations in conventional pesticide products [29, 30], but their actual AIs utilization of biological target uptake is less than 0.1% after dust drift and rainwater leaching [31].

NMs used in pesticide production mainly participate in establishing nanopesticide formulation systems to improve the bioavailability of AIs (Fig. 1), detailed reasons as follows (Fig. 2).

Nanomaterials loaded with pesticides. NMs loaded with pesticides can reduce the degradation of AIs caused by environmental influences, achieve target-controlled release of AIs by the properties of nanomaterials, thus prolonging the shelf life of pesticides; Some NMs have their own insecticidal and fungicidal activities; When applied to soil, NMs help pesticides to be fixed in the soil for plant root absorption in order to reduce the loss of pesticides by leaching

NMs improve the stability of AIs. AIs that easily undergo photolysis and are easily decomposed can be stabilized under the protection of NMs. Avermectin (AV) is an excellent bio-pesticide that has been widely used, but it is sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) light and has a very short half-life (6 h) [32]. Zhu et al. grafted AV onto the long chain of poly (ethylene glycol)-carboxymethyl cellulose (PEG-CMC), and the obtained nanoparticles improved the stability of AV significantly over the control, and the degradation rate of AV was less than 50% after 72 h of illumination [33]. Another approach is using NMs as a protective shell for AIs. Kaziem et al. encapsulated AV in hollow mesoporous silica, then anchored cyclodextrin in the outermost layer of the particles [70]. NMs now are specifically applied as bio-fertilizer; trace element fertilizers such as Fe and Zn; major element fertilizers, including N, P, and K; medium element fertilizers, for example, Si, Ca, Mg, and S. NMs are also used in organic fertilizer. In this section, we present an overview of the application of NMs for each of the fertilizer types as above.

Djaya et al. developed a composite embedding process for graphite and silica composites to encapsulate the plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and endophytic bacteria to obtain a novel biocontrol delivery system (BDS) [71]. The efficacy of the BDS was evaluated by measuring the diameter of inhibition zone against R. solanacearum culture. The results showed that compared to control, inhibition zone of the treatment of Lysinibacillus sp. was up to 10.24 times wider, and treatment of Bacillus sp. was 12.6 times respectively, which indicated the ability of BDS to form synergistic effect and inducing antagonistic interactions.

Benzon et al. found that compared to conventional fertilizer use only, combining nano-fertilizer with conventional fertilizer significantly improved the agronomic parameters of rice [72]. The plant height, chlorophyll content, number of reproductive tillers, panicles and spikelets were increased by 3.6%, 2.72%, 9.10%, 9.10% and 15.42%, respectively. Panicle weight, total grain weight, total shoot dry weight and harvest index were also improved by 17.4%, 20.7%, 15.3%, and 2.9%, respectively. Furthermore, the authors determined that the performance of using only nano-fertilizer was not noticeable and suggested using nano-fertilizer in conjunction with conventional fertilizer to achieve good results.

Haydar et al. evaluated the biological effects of iron oxide nanoparticles as well as EDTA-functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles as a nano-micronutrient fertilizer in place of conventional iron fertilizers [73]. The effect of these fertilizers on agronomic trait parameters of mulberry (Morus alba L.) was estimated in a pot experiment. The application was carried out by both foliar spraying and soil application, and iron oxide nanoparticles and their EDTA functionalized forms were applied at two different concentrations (10 and 50 mg/kg soil). The results showed positive effects on the agronomic trait parameters of the treated plants. Iron oxide nanoparticles in the soil at a concentration of 10 mg/kg significantly improved the morphological characteristics of the plants, such as germination rate, leaf number (52.73% higher than the control), plant biomass (37.20% and 90.24% increase in shoot and root biomass, respectively, compared to the control), root properties (34% increase in root length), and also reduced the time to germination of the first leaves. The same treatments increased by 42% and 15%, respectively, compared to the control for chlorophyll and sugar content. The activity of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, peroxidase and NADPH oxidase was also increased compared to the control. All results showed that iron oxide nanoparticles could replace the traditional iron fertilizer in the cultivation and propagation of mulberry crops.

Raliya et al. developed nano zinc fertilizer to increase the yield of pearl millet (Pennisetum americanum) [74]. In this study, the fungus Rhizoctonia bataticola TFR-6 (NCBI GenBank Accession number JQ675307) was cultivated in potato dextrose (PD) broth medium. The filtrate of fungus-free organism cells was isolated, which was used to prepare an aqueous zinc oxide solution with a concentration of 0.1 mM. The synthesis of nano zinc was performed by exposing the former zinc oxide solution to the fungal cell-free filtrate previously prepared for 62 h. The dynamic light scattering (DLS) results showed that the particle size of the synthesized nanoparticles ranged from 15 to 25 nm and had spherical with clear particle interfaces and crystalline structures as seen by TEM. Fertilization with the nano-fertilizer applied to 6-week-old pearl millet showed the following results: stem length (15.1%), root length (4.2%), root area (24.2%), chlorophyll content (24.4%), total soluble leaf protein (38.7%), plant dry biomass (12.5%), acid phosphatase (76.9%), alkaline phosphatase (61.7%), phytase (322.2%) and dehydrogenase (21%) activities were significantly higher than the control. The application of Zn nano-fertilizer increased the yield of the crop at maturity by 37.7%.

Li et al. found via field and indoor experiments that the long-term use of pesticides in tea gardens would cause the plants to accumulate excessive amounts of ROS, leading to oxidative damage in the plants and affecting the nutritional quality of tea [75]. In contrast, selenium nanoparticles activated the plant antioxidant system, resulting in significant increases in the content and activity of antioxidant enzymes in the ascorbic acid-glutathione cycle, which helped minimize pesticide induced oxidative damage. Biofortification with selenium significantly increased the accumulation of nutrients and functional substances such as proteins, carotenoids, tea polyphenols, and catechins in tea products. Metabolomic and transcriptomic studies have shown that selenium nanoparticles can induce theanine, glutamate, proline, and arginine production by regulating the glutamine-glutamate cycle. Nanoselenium exogenous supplementation promotes secondary metabolism in tea plants, which in turn increases the biosynthesis of total phenols and flavonoids in tea leaves. Nanoselenium promotes the uptake and conversion of selenium in the soil, leading to a significant increase in the production of selenium-rich teas with many key aroma components.

Alimohammadi et al. evaluated the effect of urea and Nano-Nitrogen Chelate (NNC) fertilizers on yield of sugarcane (Saccharum Officinarum) and nitrate leaching from soil [76]. Treatments included five different N contents of urea and NNC (0, 80, 112, 137 and 161 kg N ha−1). Results showed that the mean values of soil nitrate concentrations were 10.2 and 12.8 mg/kg for urea and NNC treatments, respectively, during sugarcane growth. The nitrate leaching level was high with urea fertilizer (699.0 mg l−1) and low with NNC fertilizer (183.0 mg l−1). This study also found that the application of NNC was significantly effective in increasing sugar content in sugarcane. Considering nitrate leaching and its impact on human health and the environment, NNC is potentially valuable.

Rajonee et al. prepared phosphorus and potassium compound nano-fertilizer using zeolite as a carrier material, and characterized and evaluated fertilization efficiency [77]. Material composition measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD) showed that the modified zeolite's peak position and height changed compared with unmodified zeolite, indicating that the K, P fertilizer element was successfully loaded into the zeolite and the nano-fertilizer was prepared successfully. An in vitro incubation study with the application of nano-fertilizer showed that the release of potassium was most prominent throughout the experiment and all experimental units showed the same trend to different degrees. The potassium content in the soil was maintained at a higher level with the nano-potassium fertilizer compared to control. Even though nano-fertilizer has promising performance, its large-scale implementation is limited by high cost.

Chen et al. revealed that CaSO4 reduced phosphorus loss from farmland through soil incubation experiments [78]. CaSO4 is a typical soil conditioner with strong complexation to orthophosphate. Compared to conventional crude CaSO4, nano calcium sulfate provides a larger surface area, higher solubility, and improved integration of fertilizer and soil, which further reduces soil phosphorus loss.

Ahanger et al. presented a nano-vermicompost organic fertilizer with particle sizes ranging from 1 µm to 200 nm after air-drying and grinding [79]. The influence of this fertilizer on the growth of tomatoes under drought stress was studied, and the results showed beneficial effects on growth, oxidative stress parameters, antioxidant, nitrogen metabolism, osmotic accumulation and mineral elements under drought stress, which demonstrated its beneficial contribution in preventing drought-mediated damage to tomatoes.

Currently, NMs in fertilizer are mostly reported from validation experiments illustrating that NMs can be used as a fertilizer directly or as auxiliary materials to indirectly improve fertilizer utilization. The lack of systematic theoretical studies on interactions and material exchange among NMs, plant root systems, root physical and microbial environments, and plant systems hinders the development and implementation of nano-fertilizer formulations.

The reported mechanisms by which NMs act as fertilizer or fertilizer synergists to affect plant growth can be summarized as the following aspects: First, reducing fertilizer particle size to nanoscale is expected to improve the solubility and dispersion potential of fertilizer nutrients. Furthermore, due to the small size effect of NMs, they have unique potential to easily pass through the membrane barriers of plant cell walls, thereby offering altered uptake kinetics of the applied nano-form fertilizers [80]. Lastly, NMs protect fertilizer by encapsulating it to reduce its volatilization, fixing it in the soil through NMs and reducing its leaching losses, thus improving its utilization and reducing environmental damage. NMs and nanotechnology in fertilizers will effectively promote fertilizers' absorption and utilization, thus improving the agronomic parameters of crops. It can also reduce the environmental pollution caused by the volatilization and leaching of chemical fertilizers.

New applications of nanomaterials in agrochemicals

In recent years, because of the environmentally friendly control strategies advocated by Integrated Pest Management, the rapid rise of organic farming, and the increased awareness of environmental protection and food safety, many eco-friendly agrochemicals, such as bio-pesticides have received lots of attention, NMs are subsequently applied to these chemicals [81].

Nanomaterials for bio-pesticide applications

The ecological and health threats associated with applying chemical pesticides are increasingly concerning. According to the reports of Tang and Tackenberg et al., in the past few years, bee numbers have decreased markedly and trace pesticides have been detected in 75% of the world's honey, particularly neonicotinoids, including imidacloprid, thiacloprid, and thiamethoxam. With this background, some environmentally-friendly agricultural solutions for pest control that pose little risk to humans and beneficial microorganisms have gained more attention [82, 83].

Compared with chemical pesticides, bio-pesticides are more eco-friendly, and they have become more common for pest and disease control in plants. Currently, the market share of bio-pesticides is increasing, with the following categories [84].

-

(1)

Microbial pesticides, developed using living microorganisms, specifically subdivided into bacterial pesticides, such as Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt), B. subtilis, and B. cereus; and fungal pesticides, such as Beauveria bassiana (Bals.), Metarhizium anisopliae, (Paecilomyces lilacinus (Thom.) Samson), and Verticillium.

-

(2)

Viral pesticides, including nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV), granulosa virus (GV), and genetically engineered rod-shaped virus.

-

(3)

Plant-derived pesticides are natural products in plants, some of which have insecticidal and fungicidal effects, such as EOs, bittersweet, pyrethrins, indocyanin.

-

(4)

Agricultural antibiotics are microbial secondary metabolites produced by bacteria, fungi, actinomycetes, and other microorganisms in the fermentation process, which can be used to control agricultural pests. Examples include AV, bupropion, erythromycin, and liuyangmycin.

-

(5)

Biochemical pesticides, such as vinblastine, erythromycin, and gibberellic acid.

-

(6)

Plant immunity elicitor-inducing antibacterial agents, which allow plants to fight against pests and diseases by enhancing their immune function, such as chitosan and activating proteins.

Bio-pesticides also include natural enemy pesticides, such as Trichogramma dendrolimi (Matsumura) and T. chilonis (Ishii).

However, bio-pesticides have their own drawbacks. For example, microbial pesticides and antibiotic pesticides are easily affected by external environment factors such as temperature, humidity, and light, making the AIs unstable. Using NMs as carriers is one way to solve the stability and utilization issues of bio-pesticides effectively (Table 2).

When Bt forms spores accompanied by the production of insecticidal crystal protein, which is a protein of length 130–140 kDa, it needs to be solubilized in an environment with a pH > 9.5 to be activated and then become toxic. The midgut of lepidopteran larvae is a strong alkaline environment, and when the larvae intake Bt, it is activated and releases 60–70 kDa of toxin, killing the target. Therefore, the smaller the particle size of Bt, the better its performance. Usually, top-down approaches of microionization are employed to make Bt in the nanoform. These approaches, including jet milling, ball milling, and high pressure homogenization, could convert the coarse powder to ultrafine powder, and are easy to scale up and give reproducible results [85]. However, the balls used in the milling may produce contamination of the final product, and heat generation during high speed milling process could reduce the viability and efficacy of Bt. Therefore, an increase of using NMs to load Bt is observed. The preparation of NMs loaded Bt could not only obtain ultrafine formulations, but also improve the stability and shelf life of biological pesticides in the environment. Zaki et al. studied the application of NMs in Bt formulations and investigated a complex of nanotubular sodium titanate and Bt as a novel nano-pesticide against cotton leaf-worm. The preparation was carried out by mixing the NMs sodium titanate and Bt in water at a mass ratio of 1:2, sonicating for 10 min, then stirring with a magnetic stirrer, and finally drying [86]. The bacterial nanocomposites showed an improvement in insecticidal activity against cotton leaf worm, Spodoptera littoralis and a stronger effect on the different biological features of pest than bacteria alone.

In order to address the poor stability and low utilization of Bt, excipients were also added to prevent settling of suspensions; preservatives were added to extend shelf life; and for powders, additives were applied to improve their wetting and spreading properties. UV shielding agents were also used to prevent rapid photolysis after spraying. These improvements resulted in a sixfold increase in the utilization of AIs [87].

Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) is a fungal microbial pesticide, usually prepared with vegetable oil and mineral oil as dispersion media to obtain oil suspensions for use. B. bassiana is susceptible to decomposition by UV irradiation, so Hersanti et al. used silica nanoparticles (Silica Nps.) and carbon fibers as carriers for B. bassiana to control potato Spodoptera litura (S. litura) [88]. Silica Nps. and carbon fibers can also be used as fertilizers to provide nutrients to plants while protecting them from biological stress. A total of 16 treatments (control treatments were included) were designed to assess the effect of applying different concentrations of the mixture B. bassiana + Silica Nps. + carbon fiber on the mortality of S. litura. The results showed that the application of the mixture of B. bassiana + Silica Nps. 5% + carbon fiber had the highest mortality rate (53.33%) on S. litura larvae, while the single B. bassiana treatment had a mortality rate of 6.67%.

Plant-derived pesticides are also important bio-pesticides, and currently, EOs and neem-derived products are the most widely used [89]. EOs, an important natural source of pesticides, are mostly lipophilic and interfere with insects' normal metabolic, biochemical, and physiological reactions, which eventually affect their behavior. NMs applied to plant EOs show a synergistic effect on EO bioactivity. Cinteza et al. mixed chitosan-coated nanosilver with EOs in specific ratios, and the physical and chemical properties and biological activity of the system remained stable after mixing. In addition, a synergistic effect from the antibacterial activity test was observed, and the mixture was effective against a wide range of microorganisms with minimal side effects [90].

NMs are applied in antibiotic bio-pesticides to raise the stability and utilization of AIs. AV is the most widely used antibiotic-based bio-pesticide. As noted earlier, NMs improved the anti-UV ability of AV, increased the biocompatibility of the AIs, and improved its utilization.

In addition, microbial pesticides and chemical pesticides can be loaded together through NMs to form a dual-functionalized system, which has a synergistic effect on the bioactivity. Cui et al. used water–oil-water double emulsion method combined with high-pressure homogenization technology to prepare PLA nanocapsules containing validamycin and thifluzamide (VTNC) for the control of rice sheath blight [91]. The VTNC shown an average diameter of 265.3 ± 0.8 nm and polydispersion index of 0.034 ± 0.030, and these spherical particles were well dispersed, smooth in surface, and equal in size. The bioactivity evaluation results of VTNC against Rhizoctonia solani. showed that dual-functionalized system was significantly better than that of the commercial formulations and a clear synergistic effect between the two AIs was observed.

Gibberellic acid (GA) is an important biochemical pesticide, and is relatively widely used. GA stimulates plant growth, such as promoting the formation of male flowers [92]. Hafez et al. used layered double hydroxides (LDH) as a potential carrier for a GA formulation [93]. GA@LDH nano-formulation was synthesized using the memory-effect property of LDH. TEM showed a hexagonal flake-like shape with a lateral dimension ranging from 10 to 20 nm. The GA@LDH nano-formulation promoted plant growth with a significant increase in stem length over the control at the same concentration, and also showed better bioavailability and improved safety compared to the control. This study highlights a potential nanohybrid formulation form of GA using the memory effect property of the LDH clay material.

As a plant immunity elicitor, chitosan stimulates plant growth, induces disease resistance in plants, and produces immunity and inactivation against various fungi, bacteria, and viruses [94]. Asgari-Targhi et al. synthesized chitosan/zinc oxide nanocomposite (CS-ZnONP) and evaluated their biologically in vitro conditions [95]. The nanocomposite was able to improve plant growth and biomass more than bare ZnONPs use. Plants with CS-ZnONP increased chlorophyll (51%), carotenoids (70%), proline (twofold) and protein (about twofold) concentrations than with bare ZnONPs. Adding CS-ZnONP to the seed medium increased enzymatic antioxidant biomarkers (catalase and peroxidase). The activity of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase showed a similar significant upward trend. CS-ZnONP treatment greatly enhanced the accumulation of alkaloids (60.5%) and soluble phenols (40%). Micropropagation experiments showed that CS-ZnONP treatment promoted organ development. Overall, CS-ZnONP can be considered as a highly effective biocompatibility elicitor.

The integrated system of pesticides and fertilizers constructed with NMs and nanotechnology can achieve the co-delivery of pesticides and fertilizers, which is of great potential in reducing labor cost and giving full play to the synergistic effects of fertilizers and pesticides [96].

Nanomaterial-mediated nucleic acid pesticides system

Nucleic acid pesticides are based on the introduction of exogenous nucleic acid fragments into the target, which interferes with the normal transcription of the target gene, resulting in the death of the target. The more studied are RNA pesticides. RNA pesticides are used to protect crops with RNA interference (RNAi) technology. RNAi delivers double-stranded (ds)RNA /small interfering (si) RNA to insects, silencing genes and affecting normal genetic coding, ultimately killing the pests (Fig. 4.) [97]. RNA-pesticides work through the initiation, effect, and cascade amplification of RNAi by Dicer-like (DCL), Argonaute(AGO), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP). The RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISC) assembled by functional small RNAs and AGO enzymes are the minimal functional units of gene silencing [98]. DCL participates in cleavage and processing of small RNA precursors (dsRNA or microRNA precursors, etc.) to form mature small RNA sequences [99]. AGO is implicated in the recognition and selective binding of small RNAs to promote the formation of functional RISC complexes and mediate target sequence degradation or translational repression [100]. RdRP is mainly associated with the generation and replication of secondary small RNAs, further enhancing and amplifying the silencing effect [101]. Therefore, functional small RNAs are the core elements of biologically mediated RNAi-dependent gene silencing, and DCL, AGO, and RdRP are critical for maintaining the generation, transmission, and amplification of RNAi-mediated gene silencing signals [115]. Attraction test showed that the nanoporous carrier exhibited better elicitation performance than commercial product under the same environment. Correia et al. also developed a composite membrane for the slow release of pheromones using poly (butylene adipate‑co‑terephthalate) and activated charcoal, which could protect the AI from climatic factors and prolong the shelf life of the pheromone [116]. The results of diffusion experiment showed that the volatility of pheromone rhynchophorol was 100% within 24 days for the control sample, while the volatility of composite membrane-coated rhynchophorol was only 45% after 65 days.

Nanomaterial loaded pheromone. Traditional pheromones products are unstable and easy to volatilize, resulting in short shelf life and unsatisfactory "Attract-and-kill" effect; Nanomaterial-loaded pheromones with environment friendly properties can realize slow-release, protect from decomposition under ambient conditions, and show excellent efficacy in the open orchard

Bhagat et al. prepared pheromone methyl eugenol (ME) nanogels using low-molecular mass gelators (LMMGs)-all-trans tri (p-phenylene ethynylene) bis-aldoxime [117]. The preparation was based on the self-assembly by weak intermolecular non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking and van der Waals) of LMMGs, which leads to specific solvent gelation. The gel system was a three-dimensional nanoscale supramolecular network structure, providing high pheromone retention capacity. In addition, the nanogel was insoluble in water, which protected ME from decomposition caused by light, temperature and humidity in the environment, thus prolonged the shelf life. The perpetration did not require the use of any additives, such as crosslinkers and antioxidants, so it was an environmentally friendly agrochemical. The results of field trap** tests showed that in the luring test of B. dorsalis, treatment 1 (ME alone) and treatment 2 (ME in nanogel) were basically equal in the first three days, while from the 8th day, treatment 2 showed a more effective effect than treatment 1. Therefore, nanogel immobilized ME was an effective agent for the control of B. dorsalis.

Future challenges in the development of nano-agrochemicals

NMs are still being explored for applications in agrochemicals, and safety assessment, production cost, evaluation standards, registration polices and public concern issues must be addressed. A critical assessment of the impact of nanoparticles is necessary before they are determined to be safe to use [118].

Environmental safety assessment

There are concerns about the potential safety risks of NMs to non-target organisms as well as to humans. Juárez-Maldonado et al. summarized that the direct interaction of NMs with microbial cells is also quite complex and may cause specific changes in microbial cell physiology and gene expression that can lead to proliferation of any kind of cell [119]; such risks may reduce the diversity and abundance of specific microbial groups in the soil [120]. Risk assessment of NMs for agrochemicals primarily remains in the laboratory stage and the real scenarios of application do not have enough risk assessment. Various application environments may lead to variable results. For the design and predict the environmental fate of the nanoscale agrochemicals, Zhang et al. proposed to integrate existing nutrient cycling and crop productivity models with nanoinformatics approaches to optimize targeting, uptake, delivery, nutrient capture, and long-term effects on soil microbial communities to design nanoscale agrochemicals that combine the best safety and functional properties [121]. Kah et al. suggested that nano-agrochemicals should be extensively tested for effectiveness and environmental effects under field conditions [122]. Further work needs to be done to evaluate nano-agrochemicals to assess the advantages and new risks of existing products in a reasonable manner.

Production cost, evaluation standards and registration policies

Though nano-enabled agrochemicals may offer a range of benefits, they are still in the early developmental stage. Several companies have deposited patents comprising numerous protocols for production and application of nano-products, whereas, the commercial nanotechnology-based products is still relatively limited in quantity and needs further development. According to the Nanotechnology Products Database available at Statistic Bank (StatNano), there are 9420 nanotechnology-based products are commercialized, only 229 nano-products launched for agriculture application [123]. Most of these products are nano-fertilizers (43%), and nanoformulations aimed at improving plant survival against disease, pest and other stress represent together 28% of these products. The high production costs and complexity of the production process make the use of NMs in agriculture a low-margin industry that cannot generate significant economic returns on the initial production investment [124]. This is a major constraint to the application of NMs in agrochemicals on a large scale. Furthermore, there is a lack of uniform methods and standards among government authorities relating to NMs [125]. The existing methods of government regulators are not applicable or cannot correctly evaluate the safety risks of nano-pesticides, and there is an urgent need to study and establish corresponding evaluation methods and standards, for the large-scale application of NMs in agrochemicals. The pesticide registration authorities in the US and European countries have issued registration policies for nano-pesticides. The US EPA has used the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) to require the registration of nano-pesticides as “new” substances and to refine relevant registration policies. The EU member states register pesticides under the Plant Protection Products Regulation, which applies to the registration of single pesticides and mixtures, regardless of size, and this includes the registration of nano-pesticides [126].

The public's acceptance of new technologies also hinders the industrialization of NMs in agriculture to a certain extent, especially as agriculture is closely related to food safety and people are likely to be sensitive to the application NMs in agriculture.

Prospects for nanomaterials applied in agrochemicals

In this review, we discussed the application of NMs and nanotechnology in plant protection, including the use of NMs in constructing nano-pesticide formulation systems, nano-fertilizers, bio-pesticides, nucleic acid pesticides, PGRs, and pheromone. We also noted the challenges of industrial production of NMs for plant protection. Although nano-agrochemical delivery is at an early stage of development, it is expected that this application will improve the efficiency of agrochemicals and reduce environment pollution. More research is required to facilitate their large-scale application. In the future, the research focus of nano-agrochemicals are as follow; (1) competition with the conventional formulations in performance, cost and scale manufacture technology, especially in the prospect of commercialization; (2) establishment of new evaluation standards of nano-agrochemicals on product quality and safety; (3) precise controlled-release systems able to response to the changes in environmental stimuli such as pH, light, temperature, enzyme activity, etc.; (4) establishment of specific using guidelines and effective large-scale field application technology of nano-agrochemicals to facilitate their extension in agriculture.

Industrial production of nano-agrochemicals prepared by NMs and nanotechnology are influenced by many factors including product economics, environmental factors, evaluation standards, using guidelines and policy issues, but the benefits of NMs and nanotechnology applied in agricultural are likely to be monumental because it can improve the efficacy, accuracy and targeting of agrochemicals. In addition, the introduction of reasonable policies and popularization of the new technology among the public are also beneficial to promote its development.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- NMs:

-

Nanomaterials

- PGRs:

-

Plant growth regulators

- NSMs:

-

Nanostructured materials

- ENMs:

-

Engineered nanomaterials

- PGRs:

-

Plant growth regulators

- AIs:

-

Active ingredients

- WP:

-

Wettable powder

- EC:

-

Emulsifiable concentrate

- AV:

-

Avermectin

- UV:

-

Ultraviolet

- PEG-CMC:

-

Poly (ethylene glycol)-carboxymethyl cellulose

- CPF:

-

Chlorpyrifos

- PA:

-

Attapulgite

- CA:

-

Calcium alginate

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- PLA:

-

Polylactic acid

- NaAlg:

-

Sodium bentonite

- EOs:

-

Essential oils

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

- PD:

-

Potato dextrose

- DLS:

-

Dynamic light scattering

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

- Zn:

-

Zinc

- Se:

-

Selenium

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- K:

-

Potassium

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- Bt :

-

Bacillus thuringiensis

- Bals.:

-

Beauveria bassiana

- NPV:

-

Nuclear polyhedrosis virus

- GV:

-

Granulosa virus

- PHSNs:

-

Porous hollow silica nanoparticles

- GA:

-

Gibberellic acid

- LDH:

-

Layered double hydroxides

- PEG-CMC:

-

Poly (ethylene glycol)-carboxymethyl cellulose

- RNAi:

-

RNA interference

- (ds)RNA:

-

Double-stranded RNA

- (si)RNA:

-

Small interfering RNA

- DCL:

-

Dicer-like

- AGO:

-

Argonaute

- RdRP:

-

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- RISC:

-

RNA-induced silencing complexes

- SWNT:

-

Single-wall carbon nanotube carriers

- pDNA:

-

Plasmid DNA

- IAA:

-

Auxin

- GA:

-

Gibberellins

- CTK:

-

Cytokinins

- ABA:

-

Abscisic acid

- ETH:

-

Ethylene

- COFs:

-

Covalent organic frameworks

- ALG/CS:

-

Alginate/chitosan

- CS/TPP):

-

Chitosan/ tripolyphosphate

- CNTs:

-

Carbon nanotubes

- ME:

-

Methyl eugenol

- LMMGs:

-

Low-molecular mass gelators

- FIFRA:

-

Federal insecticide, fungicide, and rodenticide act

References

Feynman R. P. There's plenty of room at the bottom. Engineering and science. 1959, p. 23.

Pokropivny VV, Skorokhod VV. Classification of nanostructures by dimensionality and concept of surface forms engineering in nanomaterial science. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater. 2007;27(5–8):990–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msec.2006.09.023.

Anandhi S. Nano-pesticides in pest management. J Entomol Zool Stud. 2020;8(4):685–90.

Selyutina OY, Khalikov SS, Polyakov NE. Arabinogalactan and glycyrrhizin based nanopesticides as novel delivery systems for plant protection. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27:5864–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-07397-9.

Selyutina OY, Apanasenko IE, Khalikov SS, Polyakov NE. Natural poly-and oligosaccharides as novel delivery systems for plant protection compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(31):6582–7.

Roco MC, Williams RS, Alivisatos P. Nanotechnology research directions: IWGN workshop report: vision for nanotechnology in the next decade. Berlin: Springer; 2000.

Scott N, Chen H. Nanoscale science and engineering for agriculture and food systems. Ind Biotechnol. 2013;9(1):17–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/ind.2013.1555.

de Oliveira JL, Campos EVR, Bakshi M, Abhilash PC, Fraceto LF. Application of nanotechnology for the encapsulation of botanical insecticides for sustainable agriculture: prospects and promises. Biotechnol Adv. 2014;32(8):1550–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.10.010.

Huang B, Chen F, Shen Y, Qian K, Wang Y, Sun C, Zhao X, Cui B, Gao F, Zeng Z, Cui H. Advances in targeted pesticides with environmentally responsive controlled release by nanotechnology. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(2):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8020102.

Kumar V, Vaid K, Bansal SA, Kim KH. Nanomaterial-based immunosensors for ultrasensitive detection of pesticides/herbicides: current status and perspectives. Biosens Bioelectron. 2020;165: 112382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2020.112382.

Mahmoudpour M, Karimzadeh Z, Ebrahimi G, Hasanzadeh M, Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J. Synergizing functional nanomaterials with aptamers based on electrochemical strategies for pesticide detection: current status and perspectives. Crit Rev Anal Chem. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2021.1919987.

Adams CB, Erickson JE, Bunderson L. A mesoporous silica nanoparticle technology applied in dilute nutrient solution accelerated establishment of zoysiagrass. Agrosyst Geosci Environ. 2020;3(1): e20006. https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20006.

Taşkın MB, Şahin Ö, Taskin H, Atakol O, Inal A, Gunes A. Effect of synthetic nano-hydroxyapatite as an alternative phosphorus source on growth and phosphorus nutrition of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) plant. J Plant Nutr. 2018;41(9):1148–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2018.1433836.

Fincheira P, Tortella G, Seabra AB, Quiroz A, Diez MC, Rubilar O. Nanotechnology advances for sustainable agriculture: current knowledge and prospects in plant growth modulation and nutrition. Planta. 2021;254(4):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-021-03714-0.

Dikbaş N, Cinisli KT. Microbial metabolites powered by nanoparticles could be used as pesticides in future? (NanoBioPecdicides). BJI. 2019;23(4):1–4. https://doi.org/10.9734/bji/2019/v23i430088.

Lade BD, Gogle DP. Nano-biopesticides: synthesis and applications in plant safety. In: Abd-Elsalam K, Prasad R, editors. Nanobiotechnology applications in plant protection. Nanotechnology in the life sciences. Cham: Springer; 2019.

Ten G-B. chemical innovations that will change our world: IUPAC identifies emerging technologies in chemistry with potential to make our planet more sustainable. Chem Int. 2019;41(2):12–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/ci-2019-0203.

Giraldo JP, Landry MP, Faltermeier SM, McNicholas TP, Iverson NM, Boghossian AA, Reuel FN, Hilmer JA, Sen F, Brew AJ, Strano MS. Plant nanobionics approach to augment photosynthesis and biochemical sensing. Nat Mater. 2014;13(4):400–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmat3890.

Su C, Ji Y, Liu S, Gao S, Cao S, Xu X, Zhou C, Liu Y. Fluorescence-labeled abamectin nanopesticide for comprehensive control of pinewood nematode and Monochamus alternatus hope. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(44):16555–64. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c05771.

García-Gómez C, Obrador A, González D, Babín M, Fernández MD. Comparative study of the phytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles and Zn accumulation in nine crops grown in a calcareous soil and an acidic soil. Sci Total Environ. 2018;644:770–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.356.

Li P, Huang Y, Fu C, Jiang SX, Peng W, Jia Y, Peng H, Zhang P, Manzie N, Mitter N, Xu ZP. Eco-friendly biomolecule-nanomaterial hybrids as next-generation agrochemicals for topical delivery. EcoMat. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/eom2.12132.

Pulizzi F. Nano in the future of crops. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(6):507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0475-1.

Xu T, Ma C, Aytac Z, Hu X, Ng KW, White JC, Demokritou P. Enhancing agrichemical delivery and seedling development with biodegradable, tunable, biopolymer-based nanofiber seed coatings. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(25):9537–48. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c02696.

Guha T, Gopal G, Kundu R, Mukherjee A. Nanocomposites for delivering agrochemicals: a comprehensive review. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68(12):3691–702. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06982.

Malakar A, Kanel SR, Ray C, Snow DD, Nadagouda MN. Nanomaterials in the environment, human exposure pathway, and health effects: A review. Sci Total Environ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143470.

Hussain CM. Handbook of nanomaterials for industrial applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2018.

Zheng W, Luo B, Hu X. The determinants of farmers’ fertilizers and pesticides use behavior in China: an explanation based on label effect. J Clean Prod. 2020;272: 123054. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123054.

Kaur R, Mavi GK, Raghav S, Khan I. Pesticides classification and its impact on environment. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2019;8(3):1889–97.

Kole, R. K. Improved pesticide formulation for sustainable crop protection. In: Ensuring food safety, security and sustainability through crop protection; 2021, vol. 5, p. 50–5. ISBN: 978-81-950908-4-6.

Zheng L, Cao C, Chen Z, Cao L, Huang Q, Song B. Efficient pesticide formulation and regulation mechanism for improving the deposition of droplets on the leaves of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Pest Manag Sci. 2021;77(7):3198–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6358.

Chen H, Zhi H, Liang J, Yu M, Cui B, Zhao X, Sun C, Wang Y, Cui H, Zeng Z. Development of leaf-adhesive pesticide nanocapsules with pH-responsive release to enhance retention time on crop leaves and improve utilization efficiency. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(3):783–92. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0TB02430A.

Pang Y, Qin Z, Wang S, Yi C, Zhou M, Lou H, Qiu X. Preparation and application performance of lignin-polyurea composite microcapsule with controlled release of avermectin. Colloid Polym Sci. 2020;298(8):1001–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00396-020-04664-x.

Zhu H, Shen Y, Cui J, Wang A, Li N, Wang C, Cui B, Sun C, Zhao X, Wang C, Gao F, Zhan S, Guo L, Zhang L, Zeng Z, Wang Y, Cui H. Avermectin loaded carboxymethyl cellulose nanoparticles with stimuli-responsive and controlled release properties. Ind Crop Prod. 2020;152: 112497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112497.

Kaziem AE, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Qin X, **ao Y, Zhang Y, You H, Li J, He S. α-amylase triggered carriers based on cyclodextrin anchored hollow mesoporous silica for enhancing insecticidal activity of avermectin against Plutella xylostella. J Hazard Mater. 2018;359:213–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.07.059.

Zhou M, **ong Z, Yang D, Pang Y, Wang D, Qiu X. Preparation of slow release nanopesticide microspheres from benzoyl lignin. Holzforschung. 2018;72(7):599–607. https://doi.org/10.1515/hf-2017-0155.

Liu B, Zhang J, Chen C, Wang D, Tian G, Zhang G, Cai D, Wu Z. Infrared-light-responsive controlled-release pesticide using hollow carbon microspheres@ polyethylene glycol/α-cyclodextrin gel. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(25):6981–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01265.

Wu D, Qin M, Xu D, Wang L, Liu C, Ren J, Zhou G, Chen C, Yang F, Li Y, Zhao Y, Huang R, Pourtaheri S, Kang C, Kamata M, Chen ISY, He Z, Wen J, Chen W, Lu Y. A bioinspired platform for effective delivery of protein therapeutics to the central nervous system. Adv Mater. 2019;31(18):1807557. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201807557.

Heidary M, Karimzadeh J, Jafari S, Negahban M, Shakarami J. Aphicidal activity of urea–formaldehyde nanocapsules loaded with the Thymus daenensis Celak essential oil on Brevicoryne brassicae L. Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-021-00646-w.

Zheng F, Li Y, Zhang Z, Jia J, Hu P, Zhang C, Xu H. Novel strategy with an eco-friendly polyurethane system to improve rainfastness of tea saponin for highly efficient rice blast control. J Clean Prod. 2020;264: 121685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121685.

Luo J, Zhang DX, **g T, Liu G, Cao H, Li BX, Hou Y, Liu F. Pyraclostrobin loaded lignin-modified nanocapsules: delivery efficiency enhancement in soil improved control efficacy on tomato Fusarium crown and root rot. Chem Eng J. 2020;394: 124854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2020.124854.

**ang Y, Zhang G, Chi Y, Cai D, Wu Z. Fabrication of a controllable nanopesticide system with magnetic collectability. Chem Eng J. 2017;328:320–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.046.

Shan Y, Cao L, Xu C, Zhao P, Cao C, Li F, Xu B, Huang Q. Sulfonate-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles as carriers for controlled herbicide diquat dibromide release through electrostatic interaction. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(6):1330. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20061330.

**ang Y, Zhang G, Chen C, Liu B, Cai D, Wu Z. Fabrication of a pH-responsively controlled-release pesticide using an attapulgite-based hydrogel. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2018;6(1):1192–201. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03469.

Kabir M, Tisha F, Nayan H, Islam M, Kashem M, Uddin M, Islam M, Meah M. Determining an effective and economic fungicide spray schedule for reducing blast of wheat. Int J Agr Innov Innov Technol. 2021;11(1):10–6. https://doi.org/10.3329/ijarit.v11i1.54461.

Li H, **g T, Li T, Huang X, Gao Y, Zhu J, Lin J, Zhang P, Li B, Mu W. Ecotoxicological effects of pyraclostrobin on tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) via various exposure routes. Environ Pollut. 2021;285: 117188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117188.

Li M, Xu W, Hu D, Song B. Preparation and application of pyraclostrobin microcapsule formulations. Colloid Surface A. 2018;553:578–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.06.009.

Chi Y, Chen C, Zhang G, Ye Z, Su X, Ren X, Wu Z. Fabrication of magnetic-responsive controlled-release herbicide by a palygorskite-based nanocomposite. Colloids Surf, B. 2021;208: 112115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.112115.

Wu F, Harper BJ, Crandon LE, Harper SL. Assessment of Cu and CuO nanoparticle ecological responses using laboratory small-scale microcosms. Environ Sci Nano. 2020;7(1):105–15. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9EN01026B.

Jang S, Mergaert P, Ohbayashi T, Ishigami K, Shigenobu S, Itoh H, Kikuchi Y. Dual oxidase enables insect gut symbiosis by mediating respiratory network formation. PNAS. 2021;118(10): e2020922118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2020922118.

Lu Z, Deng J, Wang H, Zhao X, Luo Z, Yu C, Zhang Y. Multifunctional role of a fungal pathogen-secreted laccase 2 in evasion of insect immune defense. Environ Microbiol. 2021;23(2):1256–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15378.

Bharani RSA, Namasivayam SKR. Biogenic silver nanoparticles mediated stress on developmental period and gut physiology of major lepidopteran pest Spodoptera litura (Fab.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)—an eco-friendly approach of insect pest control. J Environ Chem Eng. 2017;5(1):453–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2016.12.023.

Meng X, Abdlli N, Wang N, Lü P, Nie Z, Dong X, Lu S, Chen K. Effects of Ag nanoparticles on growth and fat body proteins in silkworms (Bombyx mori). Biol Trace Elem Res. 2017;180(2):327–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-017-1001-7.

Anandhi S, Saminathan VR, Yasotha P, Saravanan PT, Rajanbabu V. Nano-pesticides in pest management. J Entomol Zool Stud. 2020;8(4):685–90.

de la Rosa G, Vázquez-Núñez E, Molina-Guerrero C, et al. Interactions of nanomaterials and plants at the cellular level: current knowledge and relevant gaps. Nanotechnol Environ Eng. 2021;6:7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41204-020-00100-1.

Faiz MB, Amal R, Marquis CP, Harry EJ, Sotiriou GA, Rice SA, Gunawan C. Nanosilver and the microbiological activity of the particulate solids versus the leached soluble silver. Nanotoxicology. 2018;12(3):263–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/17435390.2018.1434910.

Tang S, Zheng J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: structural effects. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(13):1701503. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201701503.

Shafie RM, Salama AM, Farroh KY. Silver nanoparticles activity against tomato spotted wilt virus. Middle East J Appl Sci. 2018;7:1251–67.

Campos EV, Proença PL, Oliveira JL, Bakshi M, Abhilash PC, Fraceto LF. Use of botanical insecticides for sustainable agriculture: future perspectives. Ecol Indic. 2019;105:483–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.04.038.

Zheng L, Cao C, Cao L, Chen Z, Huang Q, Song B. Bounce behavior and regulation of pesticide solution droplets on rice leaf surfaces. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(44):11560–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02619.

Zhao X, Cui H, Wang Y, Sun C, Cui B, Zeng Z. Development strategies and prospects of nano-based smart pesticide formulation. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(26):6504–12. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02004.

Liu B, Wang Y, Yang F, Wang X, Shen H, Cui H, Wu D. Construction of a controlled-release delivery system for pesticides using biodegradable PLA-based microcapsules. Colloid Surface B. 2016;144:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.03.084.

Wang A, Wang Y, Sun C, Wang C, Cui B, Zhao X, Zeng Z, Yao J, Yang D, Liu G. Fabrication, characterization, and biological activity of avermectin nano-delivery systems with different particle sizes. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018;13(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-017-2405-1.

Li W, Wang Q, Zhang F, Shang H, Bai S, Sun J. pH-sensitive thiamethoxam nanoparticles based on bimodal mesoporous silica for improving insecticidal efficiency. Roy Soc open Sci. 2021;8(2): 201967. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201967.

Yin Y, Yang M, ** J, Cai W, Yi Y, He G, Dai Y, Zhou T, Jiang M. A sodium alginate-based nano-pesticide delivery system for enhanced in vitro photostability and insecticidal efficacy of phloxine B. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;247: 116677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116677.

Wang Y, Song S, Chu X, Feng W, Li J, Huang X, Zhou N, Shen J. A new temperature-responsive controlled-release pesticide formulation–poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) modified graphene oxide as the nanocarrier for lambda-cyhalothrin delivery and their application in pesticide transportation. Colloid Surface A. 2021;612: 125987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.125987.

Chun S, Feng J. Preparation of abamectin nanoparticles by flash nanoprecipitation for extended photostability and sustained pesticide release. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2021;4(2):1228–34. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.0c02847.

Chen XX, Liu YM, Zhao QY, Cao WQ, Chen XP, Zou CQ. Health risk assessment associated with heavy metal accumulation in wheat after long-term phosphorus fertilizer application. Environ Pollut. 2020;262: 114348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114348.

Zhu Q, Liu X, Hao T, Zeng M, Shen J, Zhang F, de Vries W. Cropland acidification increases risk of yield losses and food insecurity in China. Environ Pollut. 2020;256: 113145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113145.

Lowe BS, Leer DR, Frey JW, Caskey BJ. Occurrence and distribution of algal biomass and its relation to nutrients and selected basin characteristics in Indiana streams, 201–205. Sci Invest Rep. 2008. https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20085203.

Singh MD. Nano-fertilizers is a new way to increase nutrients use efficiency in crop production. Int J Agri Sci 2017; 9(7), 3831–83. http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000217.

Djaya L, Istifadah N, Hartati S, Joni IM. In vitro study of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and endophytic bacteria antagonistic to Ralstonia solanacearum formulated with graphite and silica nano particles as a biocontrol delivery system (BDS). Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2019;19: 101153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101153.

Benzon HRL, Rubenecia MRU, Ultra VU Jr, Lee SC. Nano-fertilizer affects the growth, development, and chemical properties of rice. Int J Agro and Agri Res. 2015;7(1):105–17.

Haydar MS, Ghosh S, Mandal P. Application of iron oxide nanoparticles as micronutrient fertilizer in mulberry propagation. J Plant Growth Regul. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00344-021-10413-3.

Raliya R, Saharan V, Dimkpa C, Biswas P. Nanofertilizer for precision and sustainable agriculture: current state and future perspectives. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;66(26):6487–503. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02178.

Li D, Zhou C, Zou N, Wu Y, Zhang J, An Q, Li J, Pan C. Nanoselenium foliar application enhances biosynthesis of tea leaves in metabolic cycles and associated responsive pathways. Environ Pollut. 2021;273: 116503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116503.

Alimohammadi M, Panahpour E, Naseri A. Assessing the effects of urea and nano-nitrogen chelate fertilizers on sugarcane yield and dynamic of nitrate in soil. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020;66(2):352–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2020.1727298.

Rajonee AA, Zaman S, Huq SMI. Preparation, characterization and evaluation of efficacy of phosphorus and potassium incorporated nano fertilizer. Adv Nanopart. 2017;6(02):62. https://doi.org/10.4236/anp.2017.62006.

Chen D, Szostak P, Wei Z, **ao R. Reduction of orthophosphates loss in agricultural soil by nano calcium sulfate. Sci Total Environ. 2016;539:381–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.09.028.

Ahanger MA, Qi M, Huang Z, Xu X, Begum N, Qin C, Zhang C, Ahmad N, Mustafa N, Ashraf M, Zhang L. Improving growth and photosynthetic performance of drought stressed tomato by application of nano-organic fertilizer involves up-regulation of nitrogen, antioxidant and osmolyte metabolism. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;216: 112195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112195.

Kalia A, Kaur H. Nano-biofertilizers: Harnessing dual benefits of nano-nutrient and bio-fertilizers for enhanced nutrient use efficiency and sustainable productivity. In: Pudake R, Chauhan N, Kole C, editors. Nanoscience for sustainable agriculture. Cham: Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97852-9_3.

Yaseen R, Ahmed AIS, Omer AM, Agha MKM, Emam TM. Nano-fertilizers: Bio-fabrication, application and biosafety. Nov Res Microbiol J. 2020; 4(4), 884–900. https://doi.org/10.21608/NRMJ.2020.107540.

Tang FH, Lenzen M, McBratney A, Maggi F. Risk of pesticide pollution at the global scale. Nat Geosci. 2021;14(4):206–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00712-5.

Tackenberg MC, Giannoni-Guzmán MA, Sanchez-Perez E, Doll CA, Agosto-Rivera JL, Broadie K, Moore D, McMahon DG. Neonicotinoids disrupt circadian rhythms and sleep in honey bees. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72041-3.

Dewen Q. Research progress and prospect of bio-pesticides. Plant Protect. 2013;39(5):81–9. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0529-1542.2013.05.011.

Devi PV, Duraimurugan P, Chandrika K. Chapter 10-Bacillus thuringiensis-based nanopesticides for crop protection. Nano-biopesticides today and future perspectives, Academic Press. 2019, p. 249–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815829-6.00010-3.

Zaki AM, Zaki AH, Farghali AA, Abdel-Rahim EF. Sodium titanate-bacillus as a new nanopesticide for cotton leaf-worm. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2017;11(2):725–32. https://doi.org/10.22207/JPAM.11.2.11.

de Oliveira JL, Fraceto LF, Bravo A, Polanczyk RA. Encapsulation strategies for Bacillus thuringiensis: from now to the future. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(16):4564–77. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07118.

Hersanti, Djaya L, Hidayat Y, Pratama LS, Joni IM. The effectiveness of suspension of Beauveria bassiana mixed with silica nanoparticles (NPs.) and carbon fiber in controlling Spodoptera litura. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2219, No. 1, p. 080011); 2020. AIP Publishing LLC. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0003159.

Gahukar RT, Das RK. Plant-derived nanopesticides for agricultural pest control: challenges and prospects. Nanotechnol Environ Eng. 2020;5(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41204-020-0066-2.

Cinteza LO, Scomoroscenco C, Voicu SN, Nistor CL, Nitu SG, Trica B, Jecu M, Petcu C. Chitosan-stabilized Ag nanoparticles with superior biocompatibility and their synergistic antibacterial effect in mixtures with essential oils. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(10):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8100826.

Cui J, Sun C, Wang A, Wang Y, Zhu H, Shen Y, Li N, Zhao X, Cui B, Wang C, Gao F, Zeng Z, Cui H. Dual-functionalized pesticide nanocapsule delivery system with improved spreading behavior and enhanced bioactivity. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(2):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10020220.

Dagar A, Weksler A, Friedman H, Lurie S. Gibberellic acid (GA3) application at the end of pit ripening: effect on ripening and storage of two harvests of ‘September Snow’peach. Sci Hortic. 2012;140:125–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2012.03.013.

Hafez IH, Osman AR, Sewedan EA, Berber MR. Tailoring of a potential nanoformulated form of gibberellic acid: synthesis, characterization, and field applications on vegetation and flowering. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(31):8237–45. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02761.

Katiyar D, Hemantaranjan A, Singh B, Bhanu AN. A future perspective in crop protection: chitosan and its oligosaccharides. Adv Plants Agric Res. 2014;1(1):00006. https://doi.org/10.15406/apar.2014.01.00006.

Asgari-Targhi G, Iranbakhsh A, Ardebili ZO, Tooski AH. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan encapsulated zinc oxide (ZnO) nanocomposite and its biological assessment in pepper (Capsicum annuum) as an elicitor for in vitro tissue culture applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;189:170–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.117.

Ji Y, Ma S, Lv S, Wang Y, Lü S, Liu M. Nanomaterials for targeted delivery of agrochemicals by an all-in-one combination strategy and deep learning. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(36):43374–86. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c11914.

Zhang J, Khan SA, Heckel DG, Bock R. Next-generation insect-resistant plants: RNAi-mediated crop protection. Trends Biotechnol. 2017;35(9):871–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.04.009.

Nunes CC, Dean RA. Host-induced gene silencing: a tool for understanding fungal host interaction and for develo** novel disease control strategies. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13(5):519–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00766.x.

Fukudome A, Fukuhara T. Plant dicer-like proteins: double-stranded RNA-cleaving enzymes for small RNA biogenesis. J Plant Res. 2017;130(1):33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-016-0877-1.

Kim VN. Small RNAs: classification, biogenesis, and function. Mol Cells. 2005;19(1):1–15.

Haussecker D, Huang Y, Lau A, Parameswaran P, Fire AZ, Kay MA. Human tRNA-derived small RNAs in the global regulation of RNA silencing. RNA. 2010;16(4):673–95. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.2000810.

**e Z, Johansen LK, Gustafson AM, Kasschau KD, Lellis AD, Zilberman D, Jacobsen SE, Carrington JC. Genetic and functional diversification of small RNA pathways in plants. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(5): e104. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0020104.

Yan S, Ren BY, Shen J. Nanoparticle-mediated double-stranded RNA delivery system: A promising approach for sustainable pest management. Insect Sci. 2021;28(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.12822.

Mitter N, Worrall EA, Robinson KE, Li P, Jain RG, Taochy C, Fletcher SJ, Carroll BJ, Lu GM, Xu ZP. Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat Plants. 2017;3(2):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2016.207.

Kwak S, Lew TTS, Sweeney CJ, Koman VB, Wong MH, Bohmert-Tatarev K, Snell KD, Seo JS, Chua N, Strano MS. Chloroplast-selective gene delivery and expression in planta using chitosan-complexed single-walled carbon nanotube carriers. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(5):447–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0375-4.

Demirer GS, Zhang H, Matos JL, Goh NS, Cunningham FJ, Sung Y, Chang R, Aditham AJ, Chio L, Cho M, Staskawicz B, Landry MP. High aspect ratio nanomaterials enable delivery of functional genetic material without DNA integration in mature plants. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(5):456–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0382-5.

Gaspar T, Kevers C, Penel C, Greppin H, Reid DM, Thorpe TA. Plant hormones and plant growth regulators in plant tissue culture. In vitro Cell Dev-Plant. 1996;32(4):272–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02822700.

Chen J, Cao S, ** C, Chen Y, Li X, Zhang L, Wang G, Chen Y, Chen Z. A novel magnetic β-cyclodextrin modified graphene oxide adsorbent with high recognition capability for 5 plant growth regulators. Food Chem. 2018;239:911–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.07.013.

Li N, Wu D, Li X, Zhou X, Fan G, Li G, Wu Y. Effective enrichment and detection of plant growth regulators in fruits and vegetables using a novel magnetic covalent organic framework material as the adsorbents. Food Chem. 2020;306: 125455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125455.

Santo Pereira AE, Silva PM, Oliveira JL, Oliveira HC, Fraceto LF. Chitosan nanoparticles as carrier systems for the plant growth hormone gibberellic acid. Colloid Surface B. 2017;150:141–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.11.027.

Khodakovskaya MV, Kim BS, Kim JN, Alimohammadi M, Dervishi E, Mustafa T, Cernigla CE. Carbon nanotubes as plant growth regulators: effects on tomato growth, reproductive system, and soil microbial community. Small. 2013;9(1):115–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201201225.

Chakravarty D, Erande MB, Late DJ. Graphene quantum dots as enhanced plant growth regulators: effects on coriander and garlic plants. J Sci Food Agr. 2015;95(13):2772–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.7106.

Gregg PC, Del Socorro AP, Landolt PJ. Advances in attract-and-kill for agricultural pests: beyond pheromones. Annu Rev Entomol. 2018;63:453–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-031616-035040.

Larson NR, Strickland J, Shields VD, Zhang A. Controlled-release dispenser and dry trap developments for Drosophila suzukii detection. Front Ecol Evol. 2020;8:45. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00045.

Seo SM, Lee JM, Lee HY, An J, Choi SJ, Lim WT. Synthesis of nanoporous materials to dispense pheromone for trap** agricultural pests. J Porous Mat. 2016;23(2):557–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10934-015-0109-4.

Correia PRC, Santana JS, Ramos IG, Sant Ana AEG, Goulart HF, Druzian JI. Development of membranes composed of poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) and activated charcoal for use in a controlled release system of pheromone. J Polym Environ. 2019;27(8):1781–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10924-019-01471-6.

Bhagat D, Samanta SK, Bhattacharya S. Efficient management of fruit pests by pheromone nanogels. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01294.

Rai M, Ribeiro C, Mattoso L, Duran N. Nanotechnologies in food and agriculture, Vol. 33, Cham/Heidelberg/New York/Dordrecht/London: Springer; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-14024-7.

Juárez-Maldonado A, Tortella G, Rubilar O, Fincheira P, Benavides-Mendoza A. Biostimulation and toxicity: the magnitude of the impact of nanomaterials in microorganisms and plants. J Adv Res. 2021;31:113–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.011.

Yang X, He Q, Guo F, Sun X, Zhang J, Chen Y. Impacts of carbon-based nanomaterials on nutrient removal in constructed wetlands: Microbial community structure, enzyme activities, and metabolism process. J Hazard Mater. 2021;401: 123270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123270.

Zhang P, Guo Z, Ullah S, Melagraki G, Afantitis A, Lynch I. Nanotechnology and artificial intelligence to enable sustainable and precision agriculture. Nat Plants. 2021;7(7):864–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-021-00946-6.

Kah M, Kookana RS, Gogos A, Bucheli TD. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nature Nanotech. 2018;13(8):677–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-018-0131-1.

StatNano. Home | Nanotechnology Products Database; 2021. |https://product.statnano.com/industry/agriculture. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

Younis SA, Kim KH, Shaheen SM, Antoniadis V, Tsang YF, Rinklebe J, Deep A, Brown RJ. Advancements of nanotechnologies in crop promotion and soil fertility: benefits, life cycle assessment, and legislation policies. Renew Sust Energ Rev. 2021;152: 111686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111686.

Kah M, Tufenkji N, White JC. Nano-enabled strategies to enhance crop nutrition and protection. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(6):532–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0439-5.

Beumer K. On the elusive nature of the public. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(6):510–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0468-0.

Funding

We are grateful for financial support from the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA0716704), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701825), the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFD0200500), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (CAAS-ZDRW202008), the Basic Scientific Research Foundation of National non-Profit Scientific Institute of China (BSRF201907), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFD0200300, 2017YFD0201207, 2018YFD0200200), and Technology Program for Water Pollution Control and Treatment (No. 2017ZX07101003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA and CS contributed equally to this work. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

An, C., Sun, C., Li, N. et al. Nanomaterials and nanotechnology for the delivery of agrochemicals: strategies towards sustainable agriculture. J Nanobiotechnol 20, 11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-021-01214-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-021-01214-7