Abstract

Background

In the past decade, the carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) have been reported worldwide. Emergence of carbapenemase-producing strains among Enterobacteriaceae has been a challenge for treatment of clinical infection. The present study was undertaken to investigate the characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae recovered from an outbreak that affected 17 neonatal patients in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Kunming City Maternal and Child health Hospital, which is located in the Kunming city in far southwest of China.

Methods

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for antimicrobial agents were determined according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); Modified Hodge test and Carba-NP test were preformed to identified the phenotypes of carbapenemases producing; To determine whether carbapenem resistance was transferable, a conjugation experiment was carried out in mixed broth cultures; Resistant genes were detected by using PCR and sequencing; Plasmids were typed by PCR-based replicon ty** method; Clone relationships were analyzed by using multilocus-sequence ty** (MLST) and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

Results

Eighteen highly carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae were isolated from patients in NICU and one carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolate was detected in incubator water. All these isolates harbored bla NDM-1. Moreover, other resistance genes, viz., bla IMP-4 , bla SHV-1 , bla TEM-1 , bla CTX-M-15 , qnrS1, qnrB4, and aacA4 were detected. The bla NDM-1 gene was located on a ca. 50 kb IncFI type plasmid. PFGE analysis showed that NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae were clonally related and MLST assigned them to sequence type 105.

Conclusions

NDM-1 producing strains present in the hospital environment pose a potential risk and the incubator water may act as a diffusion reservoir of NDM-1- producing bacteria. Nosocomial surveillance system should play a more important role in the infection control to limit the spread of these pathogens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gram-negative bacilli are the most important cause of healthcare associated infections [1]. Among these, Enterobacteriaceae continue to be an important cause of such infections [2], particularly the carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) in develo** countries, such as China [3]. In the past decade, the CPEs have been reported worldwide, including KPC-, GES-, VIM-, IMP-, GIM-, NDM- and OXA- types [4]. Among them, the NDM-type carbapenemase is a novel metalo-beta-lactamase that was identified for the first time in 2008 [5]. NDM-1 carbapenemase belongs to class B of Ambler β-lactamases, and efficiently hydrolyses a broad range of β-lactams, including penicillins, cephalosporins, and carbapenems, except for aztreonam. Up to this day, the emergence of carbapenemase-producing strains among Enterobacteriaceae has been a challenge for treatment of clinical infection [6].

Plasmid-mediated drug resistance is one of the most serious problems in the treatment of infectious diseases due to the horizontal transfer of plasmids account for the dissemination of resistance genes and the emergence of drug resistant strains [7, 8]. Carbapenemase-producing strains are most often associated with many non-β-lactam-resistance genes, because of their locations on plasmids [9], which made therapeutic options for infections were very limited.

Klebsiella pneumoniae was a leading cause of nosocomial infections and spread rapidly in health care settings due to efficiency of colonization and rapid development of resistance to a wide range of antimicrobials [10]. Recently, K. pneumoniae harboring bla NDM-1 were emergencing in China, which should pay great attention [11, 12]. Therefore, investigation of the molecular characteristics of NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae is critical. Here, we identified 19 K. pneumoniae harboring bla NDM-1, the transmission of these NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae among neonatal patients at Kunming City Maternal and Child health Hospital was delineated in this study.

Methods

Bacterial isolates

Kunming City Maternal and Child health Hospital was a 200-bed tertiary care community health facility in the provincial capital, Kunming City. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) isolates were rare in this facility prior to this outbreak. On January 22, 2014, one K. pneumoniae strain (M1) was isolated from a sputum specimen, obtained from a neonatal patient in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), this strain was resistant to carbapenems including imipenem and meropenem. On January 23, 2014, another carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae strain (M2) was isolated from a stool sample obtained from another neonate in the same ward. We screened the rectal swab samples taken from patients in the NICU ward; simultaneously, environmental swabs of bed linen, stethoscopes, doorknobs, and water in the neonatal incubator, and the hand swabs obtained from doctors and nurses, were also collected. All swabs were inoculated on the Mueller–Hinton plates containing 2 μg/mL meropenem. The colonies that grew on the selection medium and clinical isolates with decreased susceptibility to carbapenems were picked and identified using a VITEK 2 Compact (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France).

Detection of phenotypes

The production of carbapenemases was evaluated in all isolates using a Modified Hodge test [13] and Carba NP test [14], as previously described.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

MICs for antimicrobial agents were determined by using the microdilution susceptibility testing method, according to the guidelines of the CLSI [15]. The antibiotics tested included imipenem, meropenem, ceftazidime, aztreonam, piperacillin, piperacillin/tazobactam, tigecycline, levofloxacin, and amikacin. MIC results were interpreted as specified by CLSI [13], except for tigecycline, which was interpreted as defined by the US Food and Drug Administration (susceptible: MIC ≤ 2 mg/L; resistant: MIC ≥ 8 mg/L). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as quality control.

Detection of drug-resistant genes

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was obtained from clinical strains and transconjugants with a TIANamp Bacterial DNA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Bei**g, China). PCR and DNA sequence analysis were performed to confirm the presence of drug-resistant genes. The primers used in this study were described previously [3, 16]. β-lactamase genes, including, Ambler class A (bla CTX-M , bla TEM , bla SHV , bla KPC , bla IMI and bla GES), class B (bla VIM , bla IMP , bla NDM, and bla SPM), class C (bla CMY , bla ACT-1, and bla DHA-1), and class D (bla OXA-48) were detected in all clinical isolates and their transconjugants. Moreover, genes related to quinolone activity including qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS, integron genes and the aac gene were also detected. Products were sequenced on an ABI PRISM 3730AXL sequencer analyzer and compared with the reported sequences from GenBank.

Molecular ty**

NDM-1-producing strains were genotyped by using MLST and PFGE. Seven housekee** genes (gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, rpoB, and tonB) were amplified according to the protocol described on the MLST website [17]. PFGE were performed according to the procedure described by Pulse Net from the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [18]. Salmonella enterica serotype H9812 was used as a marker. The XbaI restriction patterns were analyzed and interpreted according to the criteria of Tenover et al. [19].

Analysis of plasmid and conjugation experiment

In order to determine whether carbapenem resistance was transferable, a conjugation experiment was carried out in mixed broth cultures. Escherchia coli J53 (AzR) was used as the recipient strain. Test strains and the recipient strain were grown separately overnight in Luria–Bertani broth at 35 °C with shaking. Cultures (2 ml) of test strains and recipient strains were mixed in a tube and incubated at 35 °C for 4 h with shaking. Then, 50 μL of the mixture was placed on Mueller–Hinton agar containing 2 μg/mL meropenem and 200 mg/L sodium azide and incubated at 35 °C for 20 h. The colonies that grew on this medium were regarded as the products of successful conjugation and were picked up and identified using a VITEK 2 Compact. Plasmid DNA from donors and transformants were extracted with a TIANprep Plasmid Maxi Plasmid Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Bei**g, China) and was electrophoresed on 0.8 % agarose gels at 100 V for 4 h. The plasmid replicons of the bla NDM-1-encoding plasmids were typed by using the PCR-based replicon ty** method described previously [20].

Results

Bacterial isolates

Eighteen carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae strains (M1–M18) were isolated from 17 patients in a variety specimens including sputum, stool, and blood; and one carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (M19) was detected in incubator water. The CRE outbreak was declared on March 31, 2014. Resistace screening was performed for all patients in the NICU until no further transmission was detected. All the 17 patients had received meropenem treatment as initial monotherapy, one patient died on February 10, 2014, while all others were recovered.

Phenotypes and drug-resistant genes

All strains (M1–M19) harbored bla NDM-1, a carbapenemase-encoding gene. M3, M5, M8, M9, M17, M18, and M19 co-harbor another carbapenemase gene bla IMP-4. Thirteen of 19 isolates showed positive phenotypic screening results for the Modified Hodge test, the positivity rate was 72 %, while the positive rate for the Carba-NP test was 100 %. Other β-lactamase genes were identified in 19 strains, including those of the bla TEM, bla CTX-M, and bla SHV. The qnr and aac genes were also detected; no AmpC-like enzymes and integron genes were found. The remaining resistance genes that were evaluated were not detected. Details on these findings are shown in Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Drug-resistance profiles were consistent between the 18 NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae clinical isolates (M1–M18) and the one NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae strain obtained from incubator water (M19). All the 19 strains were highly resistant to the tested carbapenems, including meropenem and imipenem. The MIC values for meropenem were in the range of 32–128 μg/mL and those of imipenem ranged from 4 to >128 μg/mL. Nineteen strains exhibited discrepant-level resistance to aztreonam, six isolates were sensitive, seven isolates were intermediate, and the rest six were resistant. The MIC values for the other tested β-lactam antibiotics were high (>128 μg/mL) in all tested strains. Tigecycline exhibited potent activity against all tested strains, none tigecycline reisitant strain was detected. All the isolates remained susceptible to ciprofloxacin and amikacin. These results are summarized in Table 1.

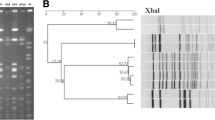

PFGE and MLST ty**

PFGE patterns of the XbaI DNA digests of 19 K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained. Gel images were input into BioNumerics and phylogenetic tree was built for cluster analysis (Fig. 1). PFGE revealed four cluster among 19 K. pneumoniae. One cluster of 16 closely related isolates was found that exhibited >90 % similarities. MLST analysis showed that all the 19 K. pneumoniae strains identified here were defined as a single sequence type (ST105) with the allelic profile 2-3-2-1-1-4-18.

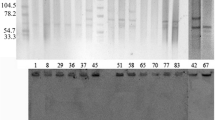

Plasmid analysis and bacterial conjugation

Carbapenems resistance was successfully transferred from all K. pneumoniae isolates to E. coli J53 (AzR) by conjugation. The MIC values of the 19 transconjugants were tested, and all E. coli transconjugants exhibited significantly reduced carbapenem susceptibility to the tested carbapenems, including imipenem and meropenem, as compared to E. coli J53 (AzR). Meanwhile, the transconjugants were resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, although not to aztreonam, and were susceptible to quinolones and aminoglycosides (Table 2). Analysis of plasmids harbored by M1–M19 and transconjugants revealed the presence of two plasmids (ca. 50 and ca. 2.3 kb), while the transconjugants only acquired the ca. 50-kb plasmid. PCR analysis confirmed that the plasmid present in transconjugants harbored both bla NDM-1 and bla SHV-1. PCR-based inc/rep ty** method showed that FIA, FIB, FIC, and F replicons were positive in all bla NDM-1- encoding plasmids, which belonged to IncFI incompatibility group.

Discussion

Emergence of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae have disseminated worldwide from the Indian subcontinent brought about problems regarding therapy and control. In China, plasmids encoding bla NDM-1 have been identified in Enterobacteriaceae isolates in several regions including Bei**g, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Shandong province, the size and Inc-type of the plasmids harbouring bla NDM-1 were vary from ~50 to ~336 kb including InX3, IncL/M, IncA/C, and IncN incompatibility group [11, 21–23]. In present study, the plasmid harbouring the bla NDM-1 belonged to the IncFI-type, which were different from previously replicon type reported in China before. Plasmid replicon types were related to the dissemination of resistance genes [22]. Due to its presence in all the 19 CREs in this study, this IncFI plasmid may be responsible for the dissemination of the bla NDM-1 in this area.

Moreover, dissemination of bla NDM-1 is associated with MLST type [24]. NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae have been reported in different countries, and belonged to various kinds of MLST types, including ST11, ST14, ST17, ST25, ST147, ST149, ST231, ST340, and ST1043 [24–29]. Our datas indicated that all 19 NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniae strains belong to the same type, viz., ST105, which was different from previous types reported before. PFGE analysis showed 4 clusters for 19 ST105 strains. Among them, one cluster of 16 closely related isolates was found that exhibited ≥90 % similarities including the strains detected in incubator water. Thoese results suggested that 19 NDM-1-producing K. pneumoniaee strains were clonally related and easily spread to different patients in NICU ward, environmental reservoirs such as incubator water may contribute to the spread of these organisms within hospital. A previous research showed that bla NDM-1 gene had disseminated in the NICU via different Gram Negative Bacilli (E. coli, A. baumannii, S. maltophilia and/or K. pneumoniae) harbouring bla NDM-1 [30]. However, it is unclear how the bla NDM-1 was introduced into the NICU ward in Kunming City Maternal and Child health Hospital. We suspect that isolates in this study represent a novel ST and that autochthonous clones are locally acquiring plasmids carrying the bla NDM-1, as has been reported previously [27], more research would be needed to uncover it.

In addition, the average days for hospitalization in Kunming City Maternal and Child health Hospital is 6.06 days at present. However, the average hospital stay of the 17 patients including in this study was 18.9 days (more than trebled of average days of hospitalization in this hospital), prolonged hospitalization may contribute to spreading of the ST105 strains in NICU ward.

The bla IMP-4 carbapenemase-encoding genes have also been detected in the part of NDM-1-producing strains (7/19). Klebsiella pneumoniae strains co-harbouring bla NDM-1 and bla IMP-4 have been identified in China previously, when they were found to be colocalized on a ca. 300-kb plasmid [31]. Plasmid analysis in this study showed that transconjugants acquired a ca. 50-kb plasmid. We analyzed the genomic DNA and plasmid DNA of 19 transconjugants by PCR, and confirmed only the presence of the bla NDM-1 and bla SHV-1. This suggested that bla IMP-4 was not on the ca. 50-kb IncFI plasmid along with bla NDM-1. We speculate that the bla IMP-4 gene may lie on the chromosome or a high molecular weight non-conjugative plasmid of which was not detected by the methodology used, further research was needed to uncover it. Bla CTX-M-15 and bla NDM-1 have a common origin in the Indian subcontinent [25] and bla CTX-M-15 had been identified in the NDM-1-producing strains, irrespective of whether the genes were located on the same plasmid [32, 33] or not [34]. Our study showed the presence of bla CTX-M-15 along with bla NDM-1 in all strains, but none of the 17 patients or their family had any epidemiological link to the Indian subcontinent. AmpCs always been detected with NMD-1 producers [28], but bla ACT-1 , bla CMY, and bla DHA-1 were not been found in this study. Although qnrB4, qnrS1 and aacA4 were detected in some strains, levofloxacin and amikacin maintained a good antibacterial activity in vitro.

Nineteen transconjugants showed increased MIC values for the tested carbapenems as compared with E. coli J53 (AzR). The MIC values of 19 transconjugants for meropenem and imipenem ranged from 16 to 32 μg/mL and 4 to 16 μg/mL respectively, which was more than fourfold higher than those of E. coli J53. Due to the transconjugants only acquired bla NDM-1 and bla SHV-1, we concluded that bla NDM-1 was primarily responsible for the high MIC values of carbapenems. In comprehensive consideration of both the MIC values of clinical isolates (M1–M18) and their transconjugants, bla IMP-4 and bla CTX-M-15 also played a role in conferring resistance to the carbapenems.

Conclusions

Hospital environment such as incubator water may be the diffusion reservoirs of NDM-1-producing bacteria. Personal contact between the caregivers and the patients hospitalized in the same ward is the most likely transmission route. However, it can not determine how this clone was introduced into the hospital, ST105 K. pneumoniae may have been spreading in hospitals in the region and their prevalence may be increasing. Therefore, nosocomial surveillance system should play a more important role in the infection control to limit the spread of NDM-1-producing pathogens.

Abbreviations

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CPE:

-

carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae

- CRE:

-

carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae

- ESBL:

-

extended-spectrum β-lactamase

- MDR:

-

multidrug-resistant

- MLST:

-

multilocus-sequence ty**

- NICU:

-

neonatal intensive care unit

- PFGE:

-

pulsed field gel electrophoresis

References

Gaynes R, Edwards JR, National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance S. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):848–54. doi:10.1086/432803.

Walsh TR, Toleman MA. The emergence of pan-resistant Gram-negative pathogens merits a rapid global political response. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(1):1–3. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr378.

Li H, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zheng R, Chen H, Wang X, et al. Molecular characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in China from 2008 to 2011: predominance of KPC-2 enzyme. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(1):63–5. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.10.002.

Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Worldwide dissemination of the NDM-type carbapenemases in gram-negative bacteria. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:249856. doi:10.1155/2014/249856.

Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, Cho HS, Sundman K, Lee K, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12):5046–54.

Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M, Tassios PT, Daikos GL. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25(4):682–707. doi:10.1128/CMR.05035-11.

Barman S, Chatterjee S, Chowdhury G, Ramamurthy T, Niyogi SK, Kumar R, et al. Plasmid-mediated streptomycin and sulfamethoxazole resistance in Shigella flexneri 3a. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(4):348–51. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.037.

Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A, Poirel L, Pitout J, Peixe L, et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(2):195–200. doi:10.3201/eid1402.070350.

Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(9):597–602.

Jarvis WR, Munn VP, Highsmith AK, Culver DH, Hughes JM. The epidemiology of nosocomial infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Control. 1985;6(2):68–74.

** Y, Shao C, Li J, Fan H, Bai Y, Wang Y. Outbreak of multidrug resistant NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from a neonatal unit in Shandong Province, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119571. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119571.

Wang X, Xu X, Li Z, Chen H, Wang Q, Yang P, et al. An outbreak of a nosocomial NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 at a teaching hospital in mainland China. Microbial Drug Res. 2014;20(2):144–9. doi:10.1089/mdr.2013.0100.

CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 23rd informational supplement. M100-S23: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2013.

Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(9):1503.

CLSI. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 9th ed. Approved standard M07-A9: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 2012.

Yang Q, Wang H, Sun H, Chen H, Xu Y, Chen M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Enterobacteriaceae with decreased susceptibility to carbapenems: results from large hospital-based surveillance studies in China. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):573–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.01099-09.

Institut pasteur MLST databases. http://bigsdb.web.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html. Accessed 19 Sep 2014.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/protocols.htm. Accessed 20 May 2008.

Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain ty**. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(9):2233–9.

Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon ty**. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63(3):219–28. doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018.

Ho PL, Lo WU, Yeung MK, Lin CH, Chow KH, Ang I, et al. Complete sequencing of pNDM-HK encoding NDM-1 carbapenemase from a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strain isolated in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17989.

Qu H, Wang X, Ni Y, Liu J, Tan R, Huang J, et al. NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a teaching hospital in Shanghai, China: IncX3-type plasmids may contribute to the dissemination of bla. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;34:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.02.020.

Zhou G, Guo S, Luo Y, Ye L, Song Y, Sun G, et al. NDM-1–producing Strains, Family Enterobacteriaceae, in Hospital, Bei**g, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(2):340.

Giske CG, Froding I, Hasan CM, Turlej-Rogacka A, Toleman M, Livermore D, et al. Diverse sequence types of Klebsiella pneumoniae contribute to the dissemination of blaNDM-1 in India, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(5):2735–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.06142-11.

Oteo J, Domingo-Garcia D, Fernandez-Romero S, Saez D, Guiu A, Cuevas O, et al. Abdominal abscess due to NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Spain. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(Pt 6):864–7. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.043190-0.

Voulgari E, Gartzonika C, Vrioni G, Politi L, Priavali E, Levidiotou-Stefanou S, et al. The Balkan region: NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 clonal strain causing outbreaks in Greece. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2014;69(8):2091–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dku105.

Escobar Perez JA, Olarte Escobar NM, Castro-Cardozo B, Valderrama Marquez IA, Garzon Aguilar MI, Martinez de la Barrera L, et al. Outbreak of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a neonatal unit in Colombia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1957–60. doi:10.1128/AAC.01447-12.

Poirel L, Dortet L, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. Genetic features of blaNDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(11):5403–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.00585-11.

Pasteran F, Albornoz E, Faccone D, Gomez S, Valenzuela C, Morales M, et al. Emergence of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Guatemala. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(7):1795–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dks101.

Roy S, Singh AK, Viswanathan R, Nandy RK, Basu S. Transmission of imipenem resistance determinants during the course of an outbreak of NDM-1 Escherichia coli in a sick newborn care unit. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(12):2773–80. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr376.

Chen Z, Wang Y, Tian L, Zhu X, Li L, Zhang B, et al. First Report in China of Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates coharboring blaNDM-1 and blaIMP-4 drug resistance genes. Microbial Drug Res. 2014. doi:10.1089/mdr.2014.0087.

Yoo JS, Kim HM, Koo HS, Yang JW, Yoo JI, Kim HS, et al. Nosocomial transmission of NDM-1-producing Escherichia coli ST101 in a Korean hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(9):2170–2. doi:10.1093/jac/dkt126.

Solé M, Pitart C, Roca I, Fàbrega A, Salvador P, Muñoz L, et al. First description of an Escherichia coli strain producing NDM-1 carbapenemase in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(9):4402.

Poirel L, Revathi G, Bernabeu S, Nordmann P. Detection of NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Kenya. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(2):934–6.

Authors’ contributions

XX designed the study; RZ drafted the first version of this manuscript; QZ collected the isolates and clinical informations; YG performed the PFGE; RZ and QZ preformed the antimicrobial susceptibility test and conjugation experiment; RZ, YF, LL, AZ, YZ, and XY carried out the molecular biology experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Escherchia coli J53 was a kind gift from Prof. Yang Qing, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University. This work was supported by Yunnan Science and Technology Commission (2013FB205, 2015BC001) from Yunnan provincial Science and Technology Department and Kunming Medical University.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Rui Zheng and Qian Zhang contributed equally to this paper

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, R., Zhang, Q., Guo, Y. et al. Outbreak of plasmid-mediated NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST105 among neonatal patients in Yunnan, China. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 15, 10 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-016-0124-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12941-016-0124-6