Abstract

Background

Global distributions and trends of the risk-attributable burdens of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have rarely been systematically explored. To guide the formulation of targeted and accurate strategies for the management of COPD, we analyzed COPD burdens attributable to known risk factors.

Methods

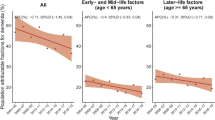

Using detailed COPD data from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019, we analyzed disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and deaths attributable to each risk factor from 1990 to 2019. Additionally, we calculated estimated annual percentage changes (EAPCs) during the study period. The population attributable fraction (PAF) and summary exposure value (SEV) of each risk factor are also presented.

Results

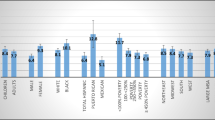

From 1990 to 2019, the age-standardized DALY and death rates of COPD attributable to smoking and household air pollution, occupational particles, secondhand smoke, and low temperature presented consistently declining trends in almost all socio-demographic index (SDI) regions. However, the decline in YLD was not as dramatic as that of the death rate. In contrast, the COPD burden attributable to ambient particulate matter, ozone, and high temperature exposure showed undesirable increasing trends in the low- and low-middle-SDI regions. In addition, the age-standardized DALY and death rates attributable to each risk factor except household air pollution and low temperature were the highest in the low-middle-SDI region. In 2019, the COPD burden attributable to smoking ambient particulate matter, ozone, occupational particles, low and high temperature was obviously greater in males than in females. Meanwhile, the most important risk factors for female varied across regions (low- and low-middle-SDI regions: household air pollution; middle-SDI region: ambient particles; high-middle- and high-SDI region: smoking).

Conclusions

Increasing trends of COPD burden attributable to ambient particulate matter, ozone, and high temperature exposure in the low-middle- and low-SDI regions call for an urgent need to implement specific and effective measures. Moreover, considering the gender differences in COPD burdens attributable to some risk factors such as ambient particulate matter and ozone with similar SEV, further research on biological differences between sexes in COPD and relevant policy-making of disease prevention are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

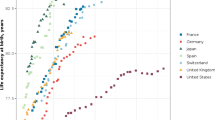

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the most pervasive chronic respiratory disease and the leading contributor to the global disease burden, increased in rank from 11 to 6th in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) among all causes between 1990 and 2019 [1, 2]. In 2019, COPD caused 3.28 million deaths and 74.43 million DALYs, 78.77 and 75.78% of which were attributable to exposure risk factors, respectively. Additionally, the prevalence and disease burden of COPD varied by sex and socioeconomic status [2]. A previous study found that low-sociodemographic index (SDI)-regions had the greatest burdens of COPD, and risk factors such as smoking and environmental pollution had the highest contributions to COPD-related mortality and DALYs [2: Figure S1, there were almost no differences in the age-standardized SEVs between males and females. Air pollution (including ambient particulate matter and ozone) is an important risk factor for COPD. But cumulative evidences suggested that women appear to be more sensitive to the effects of air pollution and smoking, because of their smaller airways (which means proportionately greater exposure), higher expression of genes involved in cytochrome P450 regulation in female, and hormonally mediated differences in pollution metabolism, etc. [13,14,15] This does not seem to support the higher COPD burden on men. On the other hand, male patients with COPD have worse survival than female patients might explain the higher disease burden of COPD to some extent [16,17,18]. Possible support for this is based on phenotypic differences between men and women in COPD [13, 19]. Chronic bronchitis is more common in women and emphysema is more common in men, the latter showing a faster decline in lung function and higher mortality. Additionally, for non-optimal temperature (including low and high temperature), it has been associated with elevated mortality risk [20, 21]. The impact of high temperature might be the alteration of fluid and electrolytic balance in COPD patients [21]. Cold weather might increase airway inflammation (TNF -α, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, etc.) [22,23,24]. Nevertheless, little is known about whether their effects differ between sexes, which need to be further explored. Therefore, based on the available evidence, the differences in disease burden caused by temperature may also be mainly due to the poorer survival of men. But alternative explanations should not be excluded.

Smoking, a key driver of COPD progression and the only behavioral risk that is controllable, is a vitally important risk factor that should be considered. It has been reported that exposure to cigarette smoke causes the destruction of the extracellular matrix, a shortage in blood supply, and the death of epithelial cells in the lungs. [25, 26] Herein, a strong correlation between smoking and COPD was confirmed once again; although smoking had the second-lowest global exposure rate compared to other risk factors, the global PAF of age-standardized DALY attributable to smoking was far larger than those of other risk factors. In addition, unlike the PAFs of other risk factors, the PAF of DALYs attributable to smoking showed remarkable heterogeneity among teenagers, middle-aged and older people. This may reflect the chronic additive effects of smoking, which are far greater than those of other risk factors. Many strategies for the control of smoking, such as economic, cultural, media-based, and family functioning measures, have been suggested in previous studies [27,28,29,30]. As the age-standardized DALY rate attributable to smoking had the steepest decline in the slope in low- and low-middle-SDI regions between 2000 and 2009, we should explore additional practicable and valid ways to generalize smoking prevention measures. Notably, as COPD is a chronic disease, there is a certain lag from the implementation of control measures to the corresponding effect.

An extremely obvious negative correlation was observed between the PAF of age-standardized DALY attributable to household air pollution and the SDI. With the development of society, the age-standardized DALY, YLL, YLD, and death rates of COPD attributable to household air pollution showed a steady downward trend but were still higher in low- and low-middle-SDI regions than in other regions. In resource-limited settings, solid fuels such as wood and cow dung, which are easily accessible, are used as cooking fuel in less-developed countries [31]. Poor ventilation and longer exposure durations also contribute to the increased rates [32]. Therefore, the COPD burden due to household air pollution in low- and low-middle-SDI regions remains a significant concern and requires more attention.

Although the age-standardized DALY, YLL, YLD, and death rates of COPD attributable to ambient particulate matter were relatively stable at the global level, the age-standardized SEVs of and COPD burdens attributable to ambient particulate matter and ozone exposure presented undesirable increasing trends in the low- and low-middle-SDI regions, suggesting that a control strategy consisting of a series of specific measures should be designed. Public health policy- and decision-makers should prioritize the design and implementation of effective ad hoc policies to address ambient particulate matter and ozone pollution.

Unlike smoking, the attributable age-standardized DALY rate and SEV of which is similar between the high-middle-SDI region and high-SDI region, the attributable age-standardized DALY rate and SEV of secondhand smoke exposure were lower in the high-SDI region than in the high-middle-SDI region. Greater limitations regarding smoking in public places may explain this finding to some extent, which is supported by an increasing body of evidence [33,34,35,36]. In addition, the age-standardized DALY and death rates caused by exposure to occupational dust was generally higher in men than in women since men have higher exposure to hazardous. However, some regions or countries with significant increases in occupational particles exposure for women also need attention. Different regions may be associated with low temperatures or high temperatures. Interestingly, relatively consistent and obvious trends of COPD burdens attributable to low and high temperatures were observed over the entire study period (the burden attributable to exposure to high temperature increased, whereas the burden attributable to low temperature decreased). This result may be influenced by global warming.

Conclusions

In summary, we need individualized measures for different high-risk groups according to their different pattern of COPD burden attributable to risk factors (e.g., the most important risk factors vary for women in different SDI regions). The DALY and death rates of COPD attributable to each risk factor except household air pollution and low temperature were the highest in the low-middle-SDI region. Notably, the undesirable increases in the COPD burdens attributable to ambient particulate matter, ozone, and high-temperature exposure in the low-middle- and low-SDI regions urgently need more attention and the implementation of relevant policies. Additionally, the observation that COPD burden attributable to ambient particulate matter, ozone, and low and high-temperature exposure is greater in males than in females, which couldn't be explained by the difference in SEV. Biological differences between male and female in COPD and its risk factors need to be further researched.

Limitations

Although this GBD study fills a gap of distributions and trends of the disease burden of COPD attributable to each risk factor, several limitations should be noted. Common deficiencies, such as the use of data based on information derived from samples not necessarily representative of the whole country/territory under study, have been explained exhaustively in many previously published GBD studies [1, 2, 4, 37]. In addition, different diagnostic thresholds for airway obstruction (expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity < 0.70, or the lower limit of normal) may influence the diagnosis rate of COPD [38]. Moreover, the issue of confounding between air pollution and smoking, which has not been addressed, inevitably produces deviation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [Global Health Data Exchange GBD Results Tool] repository, [http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool].

Abbreviations

- ASR:

-

Age-standardized rate

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DALY:

-

Disability-adjusted life year

- EAPC:

-

Estimated annual percentage change

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- PAF:

-

Population attributable fraction

- SDI:

-

Socio-demographic index

- SEV:

-

Summary exposure value

- YLD:

-

Year lived with disability

- YLL:

-

Year of life lost

References

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22.

GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):585–96.

Li X, Cao X, Guo M, **e M, Liu X. Trends and risk factors of mortality and disability adjusted life years for chronic respiratory diseases from 1990 to 2017: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ. 2020;368:m234.

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. The Lancet. 2016;388(10062):e19–23.

Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–60.

Michael J. GladePh.D. food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective, world cancer research fund/American Institute for Cancer Research, American Institute for Cancer Research, Washington, D.C. (2007). Nutrition. 2007;24(4):393–8.

Jagannathan R, Patel SA, Ali MK, Narayan KMV. Global updates on cardiovascular disease mortality trends and attribution of traditional risk factors. Curr DiabRep. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1161-2.

Davis CH, MacKinnon DP, Schultz A, Sandler I. Cumulative risk and population attributable fraction in prevention. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(2):228–35.

Liu Z, Jiang Y, Yuan H, et al. The trends in incidence of primary liver cancer caused by specific etiologies: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 and implications for liver cancer prevention. J Hepatol. 2019;70(4):674–83.

Deng Y, Zhao P, Zhou L, et al. Epidemiological trends of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer at the global, regional, and national levels: a population-based study. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):98.

Wang H, Abbas KM, Abbasifard M, et al. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1160–203.

Aryal S, Diaz-Guzman E, Mannino DM. COPD and gender differences: an update. Transl Res. 2013;162(4):208–18.

van den Berge M, Brandsma C-A, Faiz A, et al. Differential lung tissue gene expression in males and females: implications for the susceptibility to develop COPD. Eur Respir J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02567-2017.

Gut-Gobert C, Cavaillès A, Dixmier A, et al. Women and COPD: do we need more evidence? Eur Respir Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0055-2018.

Ekström MP, Jogréus C, Ström KE. Comorbidity and sex-related differences in mortality in oxygen-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35806.

Agusti A, Calverley PMA, Celli B, et al. Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res. 2010;11:122.

Perez TA, Castillo EG, Ancochea J, et al. Sex differences between women and men with COPD: a new analysis of the 3CIA study. Respir Med. 2020;171:106105.

Hong Y, Ji W, An S, Han S-S, Lee S-J, Kim WJ. Sex differences of COPD phenotypes in nonsmoking patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:1657–62.

Lam KBH. Stable or fluctuating temperatures in winter: which is worse for your lungs? Thorax. 2018;73(10):902–3.

Gasparrini A, Guo Y, Hashizume M, et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):369–75.

Donaldson GC, Seemungal T, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Effect of temperature on lung function and symptoms in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;13(4):844–9.

Lin Z, Gu Y, Liu C, et al. Effects of ambient temperature on lung function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a time-series panel study. Sci Total Environ. 2018;619–620:360–5.

Koskela HO. Cold air-provoked respiratory symptoms: the mechanisms and management. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v66i2.18237.

Hou W, Hu S, Li C, et al. Cigarette smoke induced lung barrier dysfunction, EMT, and tissue remodeling: a possible link between COPD and lung cancer. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:2025636.

Petecchia L, Sabatini F, Varesio L, et al. Bronchial airway epithelial cell damage following exposure to cigarette smoke includes disassembly of tight junction components mediated by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Chest. 2009;135(6):1502–12.

Nichter M. Smoking: what does culture have to do with it? Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):139–45.

Ho SY, Chen J, Leung LT, et al. Adolescent smoking in Hong Kong: prevalence, psychosocial correlates, and prevention. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(6S):S19–27.

Knight J, Chapman S. “Asian yuppies…are always looking for something new and different”: creating a tobacco culture among young Asians. Tob Control. 2004. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2004.008847.

Naslund JA, Kim SJ, Aschbrenner KA, et al. Systematic review of social media interventions for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2017;73:81–93.

Zahno M, Michaelowa K, Dasgupta P, Sachdeva I. Health awareness and the transition towards clean cooking fuels: evidence from Rajasthan. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231931.

Balmes JR. Household air pollution from domestic combustion of solid fuels and health. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):1979–87.

Moore GF, Holliday JC, Moore LAR. Socioeconomic patterning in changes in child exposure to secondhand smoke after implementation of smoke-free legislation in Wales. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(10):903–10.

Rigotti NA, Pashos CL. No-smoking laws in the United States. An analysis of state and city actions to limit smoking in public places and workplaces. JAMA. 1991;266(22):3162–7.

Ruprecht A, Boffi R, Mazza R, Rossetti E, De Marco C, Invernizzi G. A comparison between indoor air quality before and after the implementation of the smoking ban in public places in Italy. Epidemiol Prev. 2006;30(6):334–7.

Wei Y, Borland R, Zheng P, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of comprehensive smoke-free legislation in indoor public places in Shanghai China. IJERPH. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204019.

Collaborators GBDCRD. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):691–706.

Miller MR, Levy ML. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: missed diagnosis versus misdiagnosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3021.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely appreciate the great works by the Global Burden of Disease study 2019 collaborators.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [2016YFF0101504, 2020YFC2004702]; the National Science Foundation of China [81630011, 81970364, 81970070, 82070079, 81970011, 81770053, 81870171]; Health Commission of Hubei Province scientific research project Grant [WJ2021Q016]; the Hubei Science and Technology Support Project [2019BFC582, 2018BEC473] and Medical flight plan of Wuhan University [TFJH2018006].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In our study, YML, PW, and HL contributed equally, designed the project, edited manuscript, supervised the study, and were guarantor of the paper. JHZ, TS, XHS, and Y-ML designed study, analyzed data, and wrote the first draft. FL, M-MC collected data and contributed to data analysis. ZC and PZ performed the statistical analysis. Y-XJ, X-JZ, Z-GS, and JJC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that we had no conflicts of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The age-standardized DALY rate of COPD attributable to risk factors across different SDI regions, in 2019. Table S2. The temporal trends of age-standardized YLL rate attributed to risk factors across different SDI regions, 1990–2019. Table S3. The temporal trends of age-standardized YLD rate attributed to risk factors across different SDI regions, 1990–2019. Table S4. The temporal trends of age-standardized death rate attributed to risk factors across different SDI regions, 1990–2019.

Additional file 2: Figure S1.

Age-standardized rate of SEV of 8 main risk factors by SDI quintiles and sex from 1990 to 2019. Figure S2. Contributions of 8 main risk factors to the PAF of age-standardized death due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by different SDI quintiles and sexes from 1990 to 2019. Figure S3. Contributions of 8 main risk factors to the PAF of age-standardized YLD due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by different SDI quintiles and sexes from 1990 to 2019. Figure S4. Contributions of 8 main risk factors to the PAF of age-standardized YLL due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by different SDI quintiles and sexes from 1990 to 2019. Figure S5. The global burden of COPD attributable to occupational particles over the past 30 years. Figure S6. The global burden of COPD attributable to secondhand smoke over the past 30 years. Figure S7. The global burden of COPD attributable to ambient ozone pollution over the past 30 years. Figure S8. The global burden of COPD attributable to high temperature over the past 30 years. Figure S9. The global burden of COPD attributable to low temperature over the past 30 years.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, J., Sun, T., Song, X. et al. Distributions and trends of the global burden of COPD attributable to risk factors by SDI, age, and sex from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of GBD 2019 data. Respir Res 23, 90 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02011-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02011-y