Abstract

Background

A current issue in workforce planning is ensuring healthcare professionals are both competent and willing to work with older adults with complex needs. This includes dementia care, which is widely recognised as a priority. Yet research suggests that working with older people is unattractive to undergraduate healthcare students.

Methods

The aim of this systematic review and narrative synthesis is to explore the factors related to healthcare (medical and nursing) student preferences’ for working with older people and people with dementia. Searches were conducted in five databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINHAL, BNI, ERIC. Screening, data extraction and quality appraisal were conducted by two independent reviewers. A narrative, data-based convergent synthesis was conducted.

Results

One thousand twenty-four papers were screened (139 full texts) and 62 papers were included for a narrative synthesis. Factors were grouped into seven categories; student characteristics, experiences of students, course characteristics, career characteristics, patient characteristics, work characteristics and the theory of planned behaviour.

Conclusion

Health educators should review their role in cultivating student interest in working with older adults, with consideration of student preparation and the perceived value of this work. There is a lack of evidence about the career preferences of students in relation to dementia, and this warrants further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The demographics of the world’s population are changing, as people are living longer [1, 2]. The impact on healthcare is pervasive. Older people are frequent users of healthcare services with high multi-morbidly [3, 4]. Healthcare professionals are likely to work with older adults regardless of their speciality or healthcare setting. Increasing the capacity of the healthcare workforce to provide competent and effective care for older adults is an international concern [2]. This includes the need for more specialists in the care of the elderly, such as geriatricians and gerontological nurses [5, 6] as well as generalists with adequate skills in older adult care [2, 7]. Despite this need, working with older adults and the associated specialities is consistently documented as unpopular with healthcare students [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Career preferences formed during training can be predictive of future career choices and behaviour in practice [14, 15]. Therefore, it is important to understand the factors that may influence student preferences for consideration in education and workforce planning.

Previous systematic reviews have explored the factors associated with a low preference of working with older adults in nursing students [16,17,18] and geriatrics in medical students [19]. However, no reviews have included papers of both nursing and medical students allowing direct comparisons to be made. Also, previous reviews have only included preferences for either geriatrics or long-term care settings and excluded studies of educational interventions. Finally, none have included preferences for working with people with dementia where education and care practices are internationally recognised as suboptimal [20,21,22]. This review therefore sought to explore comprehensively the potential factors related to preferences of healthcare students in relation to working with older people and people with dementia using broad criteria for these preferences, comprising any specialities, settings or patient populations related to older people.

Method

A protocol was written adhering to PRISMA-P guidelines [23] and registered on The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews-CRD42018104647 [24].

Eligibility criteria

A summary of the eligibilty criteria is presented in Table 1.

Population

The population of interest included medical and nursing students and excluded all other healthcare disciplines. Studies that involved an additional student group were excluded unless findings were separately identified for medical and/or nursing students.

Construct of interest

The construct of interest was student preferences for working with older adults or people with dementia. Due to variability in terms, this included measures of ‘intent to work’, ‘career choices’ or in medical students ‘speciality choice or interest’. There was no restriction on the type of measures of career preferences. Qualitative explorations of preferences were included. The types of preference measured required direct relevance to older adults or dementia. This included preferences measured in relation to patient populations, specialities and settings associated with older adults or dementia.

Types of studies

All empirical articles were included, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies and theses. Conference reports or opinion pieces were excluded. Studies must have been published in English. Only studies published from 1995 onwards were included. Studies explored career preferences with associated factors or educational interventions. If a study only explored the relationship between an intervention and career preferences, a comparison group was required for inclusion.

Information sources

The initial search was conducted on the 20th September 2018 on the following databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINHAL, BNI, ERIC and google scholar. To identify further possible relevant articles, the references of included articles and relevant systematic reviews were searched.

Search strategy

Initial search terms were formed during sco** exercises. A specialist librarian was consulted to inform the final search strategy. Key terms included: ((preference adj3 work*)“ “career preference” or “career choice” or “intent* to work” or speciali*ation or “career intent*” or “special*ty choice” or “special*ty interest”) AND (“older adult*” or “older people” or elder* or dementia or geriatric* or aged) AND (student* ad j3 nurs* or “medical student*” or “allied health* student*” or “health* student*). Index terms (e.g MeSH) were also used alongside these key terms. An example search is included in Additional file 1.

Study selection

Identified references were added to EndNote (version X7). After duplicates were removed, articles were screened against eligibility criteria independently by two reviewers (MH & JS) by title and abstract, and then by full text. If there was disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted (SD).

Data extraction and analysis

An extraction template was developed and piloted by the reviewing team (MH, JS, GS, SD) and can be seen in Additional file 2. Only relevant data to preferences was extracted and only data related to nursing or medical students. Statistical probability set at < 0.05, or else recorded as non-significant. For qualitative studies: only major themes (with clear description/quotes), clearly related to preferences, were included as factors.

Papers were extracted independently by two reviewers; MH and either GS and JS, with disagreements resolved by SD. Papers that presented results from the same study were consolidated, to avoid conflation of results.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias was explored using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) scale [25], as it takes particular consideration of mixed-method studies [26]. Each paper was rated during extraction by two independent reviewers. Papers were not excluded based on MMAT scores due to the exploratory nature of this review. A narrative description of the overall quality is presented with MMAT scores.

Synthesis

A narrative synthesis approach [27] was used as it allows integration of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method studies and a quantitative meta-synthesis would not be possible due to the variability of definitions and measurements for career preferences. The use of mixed-method studies means that a data-based convergent synthesis was used [26]. Factors were identified by researchers inductively, using the most consistently used terms by the authors of papers where possible. The labelling of factors for both quantitative variables and qualitative themes were considered with the team to assess fit.

Results

Study selection

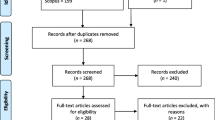

Figure 1 below outlines the number excluded at each stage.

Sixty-six papers were included for data extraction. Four studies were excluded during extraction because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. This comprised 56 unique studies (62 papers) after considering the multiple publication of data. An overview of each study is presented in Additional file 3.

Studies characteristics

The majority of studies were cross-sectional in design (n = 30). There were nine quasi-experimental studies, seven qualitative, seven longitudinal studies and three mixed-method designs.

The highest number of studies was from the USA (n = 14) followed by Australia (n = 6), Canada (n = 5), UK (n = 5) and Israel and China (n = 3). There were two papers each from Hong Kong, Turkey, Taiwan, Sweden, Saudi Arabia, and one from Finland, Ireland, Jordon, New Zealand, Norway, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Sri-Lanka. One paper compared results from Australia and China.

Thirty-eight studies investigated the preferences of nursing students, 17 of medical students, with only a single study exploring both.

Career preference definitions

Of the 18 studies that explored preferences of medical students, 16 investigated interest, willingness or likelihood of pursuing geriatrics, one explored preferences for working with older people and a single study looked at preferences towards working with people with dementia.

The type of career preferences explored for nursing students was varied and was often inconsistent within studies. Only one study investigated the intention to work in dementia care [28]. The majority of studies looked at preferences for working with older people.

Measurements of career preferences

The most common type of quantitative measure of preferences was a single item (n = 23). Eleven studies used a variation of a ranking scale, with the most common based on the work of Stevens and Crouch [29]. Unique scales were described in 14 studies, including one measure of dementia preference [28].

In the seven qualitative studies, methods of investigating preferences included focus groups (n = 4), individual interviews (n = 2) and a semi-structured questionnaire (n = 1). Other qualitative methods used included reflective essays and open text questions.

Research quality

Research quality was variable. Out of a possible score of five on the MMAT, 6 studies scored two, 21 scored three, 22 scored four and 7 scored five. Individual scores are presented in Additional file 3. Consistent issues included the use of non-standardised measures and poor construct definition. Additionally, where educational interventions were evaluated, these often lacked control groups or did not allow for confounding variables. Finally, longitudinal studies had constantly low follow up rates (< 60% for follow up).

Narrative synthesis

A summary of synthesised factors associated with preferences for working with older people or people with dementia can be seen in Additional file 4. Factors are represented by either quantitative variables or qualitative themes. These factors were grouped into seven categories, which are discussed as follows:

- 1.

Student characteristics

- 2.

Experiences of students

- 3.

Course characteristics

- 4.

Career characteristics

- 5.

Patient characteristics

- 6.

Work characteristics

- 7.

Theory of planned behaviour

Student characteristics

Demographics

There was support for a positive association of preference with female gender [9, 30,31,32,33,34]. The relationship with age was limited and inconsistent; a greater preference in younger nursing students was found for working with older people [78].

Theory of planned behaviour

The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) was used as a theoretical model in four studies of nursing preferences; TPB is a model which seeks to explain influencing factors on behaviour [79]. It suggests that people’s behaviour is a rational outcome of considering their ability to perform the behaviour (perceived behavioural control), their beliefs in society and significant others opinions on the behaviour (subjective norms) and individual attitudes to the behaviour. In this reviewed literature, the ‘behaviour’ is a career working with older adults and ‘intention’ is the preference for working with older people. The majority of these studies looked at preferences as the primary outcome rather than behaviour. Only a single study looked at actual behaviour, which was associated with preferences [62]. There was support for attitudes (to behaviour), subjective norms and perceived behavioural control as factors associated with preferences [14, 31, 51, 62].

Discussion

This review has outlined seven categories of potential factors contributing to the preferences of working with older people and provided a comprehensive overview of existing literature for medical and nursing students in this area. This model derived from the literature may have value in understanding healthcare students’ career preferences and designing education to promote work with older adults and people with dementia.

Key findings and implications

The role of undergraduate education

Student preferences for working with older people appear to decrease during training. One explanation is that education has a role in sha** perceptions of the field as low status with an emphasis on technical specialities; this socialisation process is seen as a deterrent for aged care [11, 80]. This has been referred to as a ‘hidden curriculum’ [81]. Key impactful areas during education are clinical placements and educational interventions. The literature suggests these experiences can be key to forming preferences. Nevertheless, the quality of placements, not simply exposure, appears important for promoting professions related to older adults. Examples of quality nursing placement characteristics are found in descriptions of ‘enriched environments’ [64]. These are identified by delivering a sense of security and belonging for the students at the start of their placement, creating purpose and achievement through learning, and reinforcement of the value and significance of gerontology as a profession [64]. The contribution of mentors was also highlighted [52, 66, 67]. Clinical placements and educational interventions should be reviewed to assess the impact upon preferences towards older people. Knowledge on the mechanisms by which placements can influence preferences is limited, but they are suggested to influence via the factors outlined: attitudes; perception of the field; and student preparedness, knowledge and confidence [16, 64] However, robust evaluations of educational interventions in terms of preferences are lacking.

Perceived characteristics of work, patients and career

The characteristics of the work, patients and career, identified in the direct context of influencing preferences, provide insight into why students find working with older people unattractive. This includes the perception of the work as ‘boring’, emotionally challenging, the focus on patient quality of life as opposed to cure as a barrier, the nature of patients’ illness, and communication difficulties, as well as perceived negative aspects of older patients’ disposition. Together this indicates a perception that working with older people and dementia is less valued and challenging. The implication of this is that these perceived barriers may be reduced through education by: establishing the value and improving the profile of work with older people; including the importance and role of healthcare professionals in enhancing quality of life in chronic conditions; and by targeted skill development in perceived areas of difficulty, such as communication and emotional situations. However, while some of these perceptions can be challenged, we must acknowledge the reality of the environmental aspects and career limitations that students recognise. For example, inadequate older peoples services [2] and lack of prestige as described by doctors in geriatrics [82, 83]. Previous authors have suggested how these perceptions explain the unpopularity despite relative high attitudes to older people [31, 73]. Therefore, systemic changes are needed in older people’s services; however, this could be facilitated by inspiring newly qualified healthcare professionals who are able to drive these changes.

Preferences for working with people with dementia

There was a paucity of research in relation to dementia; only two studies explored preferences specifically in relation to working with people with dementia. Potential factors included: female gender; older students; characteristics of the work such as communication and emotional challenges; and educational interventions. Of the factors related to older people, those specifically of relevance include the value of work that appears to stem from the negative perception of chronic and progressive illness and the role of healthcare professionals facilitating quality of life rather than cure. This is pertinent to working with people with dementia.

Two studies mentioned dementia in relation to the importance of exposure to healthy adults to reduce stereotypical prejudices and promote working with older people [31, 78]. The question is how to reconcile this with the evident need for dementia education. A number of new educational programmes are being developed to meet this need [84, 85]. Results suggest the importance of positive clinical experiences and potential for educational interventions to influence preferences positively in dementia-related fields [70]. The implication of these results is that these interventions may offer a way to stimulate interest (both generalist and specialist) but robust evaluations are necessary.

Medical and nursing students

Similar factors were evidenced by both nursing and medical students, specifically, the perceptions of patients and characteristics of work as well as attitudes. The main divergence around was aspects of career pathways leading to differences. There was also more literature on nursing students with more diversity in the types of nursing preferences explored, this is likely due to the nursing career paths being relatively unstructured comparatively to medicine. The inclusion of both medical and nursing students is a strength of this review as this is a multi-professional issue and allows preferences to be view in this context of both wider policy and education.

Future work

Significant gaps in research include an exploration of positive factors, longitudinal data, validated preferences measures and clear definitions of preferences. There is also a paucity of robust evaluations of education interventions and understanding of mechanisms of influence. The development of conceptual frameworks would be critical in hel** to conceptualise these factors and the relationships between them. One clear area for future research is preferences related to dementia.

Limitations

Studies were not excluded based on quality, which could have introduced bias into the review [25]. However, this was an exploratory review looking at possible factors with the aim to be comprehensive. Secondly, we have grouped different types of preferences together, although many studies did not define either what they meant by working with older adults or equate particular settings with working with older adults. Future work should provide definitions, including considering interpretations of student responders. Finally, the analysis was restricted to a narrative synthesis and therefore the magnitude of associations was not examined, giving no indication on the relative weighting of factors. Furthermore, we did not make a distinction between univariate links and multivariate analysis; given that many of the studies explored preferences not as the primary outcome, with multiple correlations being presented, there is the risk of type-1 error. However, this review has three main strengths: a rigorous systematic review methodology; it is novel in its inclusion of medical and nursing students in older adult’s preferences; and it is the first to explore preferences for working with people with dementia.

Conclusion

Seven overall categories of factors were found and provide implications for education to promote working with older people. It was found that while there is a wide and varied literature relating to older adults, understanding of factors associated with working with dementia specifically is limited and is a key area for future research.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- TPB:

-

Theory of planned behaviour

References

United Nations. World Population Prospects 2019: The Highlights.: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2019.

World Health Organaisation. World report on ageing and health. Luxembourg: World Health Organaisation; 2015.

Banerjee S. Multimorbidity--older adults need health care that can count past one. Lancet (London, England). 2015;385(9968):587–9.

Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43.

Fisher JM, Garside M, Hunt K, Lo N. Geriatric medicine workforce planning: a giant geriatric problem or has the tide turned? Clin Med (London, England). 2014;14(2):102–6.

Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008.

Oakley R, Pattinson J, Goldberg S, Daunt L, Samra R, Masud T, et al. Equip** tomorrow's doctors for the patients of today. Age Ageing. 2014;43:442–7.

Hayes LJ, Orchard CA, Hall LM, Nincic V, O'Brien-Pallas L, Andrews G. Career intentions of nursing students and new nurse graduates: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2006;3(1):0–15.

Diachun LL, Hillier LM, Stolee P. Interest in geriatric medicine in Canada: how can we secure a next generation of geriatricians? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):512–9.

King BJ, Roberts TJ, Bowers BJ. Nursing student attitudes toward and preferences for working with older adults. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2013;34(3):272–91.

Stevens JA. Student nurses’ career preferences for working with older people: a replicated longitudinal survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(8):944–51.

McCann TV, Clark E, Lu S. Bachelor of nursing students career choices: a three-year longitudinal study. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(1):31–6.

Voogt SJ, Mickus M, Santiago O, Herman SE. Attitudes, experiences, and interest in geriatrics of first-year allopathic and osteopathic medical students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):339–44.

Ben Natan M, Danino S, Freundlich N, Barda A, Yosef RM. Intention of nursing students to work in geriatrics. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2015;8(3):140–7.

Goldacre MJ, Laxton L, Lambert TW. Medical graduates' early career choices of specialty and their eventual specialty destinations: UK prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c3199.

Garbrah W, Valimaki T, Palovaara M, Kankkunen P. Nursing curriculums may hinder a career in gerontological nursing: An integrative review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2017;12(3):e12152.

Neville CPRNF, Dickie RRNBNM, Goetz SRNMM. What's stop** a career in Gerontological nursing?: literature review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2014;40(1):18–27 quiz 8-9.

Sizer SM, Burton RL, Harris A. The influence of theory and practice on perceptions about caring for ill older people a literature review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;19:41–7.

Meiboom AA, de Vries H, Hertogh CM, Scheele F. Why medical students do not choose a career in geriatrics: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:101.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017–2025. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

Department of Health. Prime Minister Challenge on Dementia 2015-2020. London: Department of Health; 2015.

Bhatt J, Comas Herrera A, Amico F, Farina N, Gaber S, Knapp M, et al. The World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. 2019.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Chien PFW, Khan KS, Siassakos D. Registration of systematic reviews: PROSPERO. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;119(8):903–5.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Industry Canada: Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office; 2018.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):61.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme 2006.

McKenzie EL, Brown PM. Nursing students' intentions to work in dementia care: influence of age, ageism, and perceived barriers. Educ Gerontol. 2014;40(8):618–33.

Stevens J, Crouch M. Frankenstein's nurse! What are schools of nursing creating? Collegian. 1998;5(1):10–5.

Koskinen S. Nursing students and older people nursing. Towards a future career; 2016.

Che CC, Chong MC, Hairi NN. What influences student nurses' intention to work with older people? A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;85:61–7.

Boyle V, Shulruf B, Poole P. Influence of gender and other factors on medical student specialty interest. N Z Med J. 2014;127(1402):78–87.

Chua MP, Tan CH, Merchant R, Soiza RL. Attitudes of first-year medical students in Singapore towards older people and willingness to consider a career in geriatric medicine. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2008;37(11):947–51.

Ní Chróinín D, Cronin E, Cullen W, O'Shea D, Steele M, Bury G, et al. Would you be a geriatrician? Student career preferences and attitudes to a career in geriatric medicine. Age Ageing. 2013;42(5):654–7.

Shen J, **ao LD. Factors affecting nursing students' intention to work with older people in China. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32(3):219–23.

Lee ACK, Wong AKP, Loh EKY. Score in the Palmore’s aging quiz, knowledge of community resources and working preferences of undergraduate nursing students toward the elderly in Hong Kong. Nurse Educ Today. 2006;26(4):269–76.

Zisberg APRN, Topaz MMARN, Band-Wintershtein TP. Cultural- and educational-level differences in students knowledge, attitudes, and preferences for working with older adults: an Israeli perspective. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26(2):193.

**ao LD, Shen J, Paterson J. Cross-cultural comparison of attitudes and preferences for Care of the Elderly among Australian and Chinese Nursing Students. J Transcult Nurs. 2013;24(4):408–16.

Zakari NMA. Attitudes toward the elderly and knowledge of aging as correlates to the willingness and intention to work with elderly among Saudi nursing students; 2005;Ph.D. p. 236.

Alsenany S. An exploration of the attitudes, knowledge, willingness and future intentions to work with older people among Saudi nursing students in baccalaureate nursing schools in Saudi Arabia; 2010.

Chi MJ, Shyu ML, Wang SY, Chuang HC, Chuang YH. Nursing students’ willingness to care for older adults in Taiwan. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(2):172–8.

Haron Y, Levy S, Albagli M, Rotstein R, Riba S. Why do nursing students not want to work in geriatric care? A national questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(11):1558–65.

Diachun LL, Dumbrell AC, Byrne K, Esbaugh J. But does it stick? Evaluating the durability of improved knowledge following an undergraduate experiential geriatrics learning session. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):696–701.

Gould ON, MacLennan A, Dupuis-Blanchard S. Career preferences of nursing students. Can J Aging. 2012;31(4):471–82.

Happell B, Brooker J. Who will look after my grandmother? Attitudes of student nurses toward the care of older adults. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(12):12–7.

Cheng M, Cheng C, Tian Y, Fan X. Student nurses' motivation to choose gerontological nursing as a career in China: a survey study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(7):843–8.

Fitzgerald JT, Wray LA, Halter JB, Williams BC, Supiano MA. Relating medical Students' knowledge, attitudes, and experience to an interest in geriatric medicine. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):849–55.

Schigelone AS, Ingersoll-Dayton B. Some of my best friends are old: a qualitative exploration of medical Students' interest in geriatrics. Educ Gerontol. 2004;30(8):643–61.

Zhang S, Liu Y-H, Zhang H-F, Meng L-N, Liu P-X. Determinants of undergraduate nursing students' care willingness towards the elderly in China: Attitudes, gratitude and knowledge. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;43:28–33.

Briscoe VJ. The effects of gerontology nursing teaching methods on nursing student knowledge, attitudes, and desire to work with older adult clients; 2004;Ph.D. p. 127.

de Guzman AB, Jimenez BCB, Jocson KP, Junio AR, Junio DE, Jurado JBN, et al. Filipino nursing Students' behavioral intentions toward geriatric care: a structural equation model (SEM). Educ Gerontol. 2013;39(3):138–54.

Fagerberg I, Winblad B, Ekman SL. Influencing aspects in nursing education on Swedish nursing students' choices of first work area as graduated nurses. J Nurs Educ. 2000;39(5):211–8.

Curran MA, Black M, Depp CA, Iglewicz A, Reichstadt J, Palinkas L, et al. Perceived barriers and facilitators for an academic career in geriatrics: medical students’ perspectives. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(3):253–8.

Ayoǧlu FN, Kulakçı H, Ayyıldız TK, Aslan GK, Veren F. Attitudes of Turkish nursing and medical students toward elderly people. J Transcult Nurs. 2014;25(3):241–8.

Darling R, Sendir M, Atav S, Buyukyilmaz F. Undergraduate nursing students and the elderly: an assessment of attitudes in a Turkish university. Gerontol Geriatri Educ. 2018;39(3):283–94.

Hweidi IM, Al-Obeisat SM. Jordanian nursing students' attitudes toward the elderly. Nurse Educ Today. 2006;26(1):23–30.

Rathnayake S, Athukorala Y, Siop S. Attitudes toward and willingness to work with older people among undergraduate nursing students in a public university in Sri Lanka: a cross sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;36:439–44.

Henderson J, **ao L, Siegloff L, Kelton M, Paterson J. Older people have lived their lives': first year nursing students' attitudes towards older people. Contemp Nurse. 2008;30(1):32–45.

Lu W-H, Hoffman KG, Hosokawa MC, Gray MP, Zweig SC. First year medical students' knowledge, attitudes, and interest in geriatric medicine. Educ Gerontol. 2010;36(8):687–701.

Pan IJ, Edwards H, Chang A. Taiwanese nursing Students' attitudes toward older people. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(11):50–5.

Hughes NJ, Soiza RL, Chua M, Hoyle GE, MacDonald A, Primrose WR, et al. Medical student attitudes toward older people and willingness to consider a career in geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):334–8.

Dunkle SE, Hyde RS. Predictors and subsequent decisions of physical therapy and nursing students to work with geriatric clients: an application of the theory of reasoned action. Phys Ther. 1995;75(7):614–20.

Robbins TD, Crocker-Buque T, Forrester-Paton C, Cantlay A, Gladman JRF, Gordon AL. Geriatrics is rewarding but lacks earning potential and prestige: responses from the national medical student survey of attitudes to and perceptions of geriatric medicine. Age Ageing. 2011;40(3):405–8.

Brown J, Nolan M, Davies S, Nolan J, Keady J. Transforming students' views of gerontological nursing: realising the potential of 'enriched' environments of learning and care: a multi-method longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45(8):1214–32.

Gates K, Santos EJ, Nguyen M, Granovskaya I, Servidio A, Turzanski M. Gerontology education initiatives in the health sciences: seeking advice from students in focus group conversations. Perspectives. 2009;33(3):6–13.

Carlson E, Idvall E. Who wants to work with older people? Swedish student nurses' willingness to work in elderly care--a questionnaire study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(7):849–53.

Lea E, Mason R, Eccleston C, Robinson A. Aspects of nursing student placements associated with perceived likelihood of working in residential aged care. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(5–6):715–24.

Abbey J, Abbey B, Bridges P, Elder R, Lemcke P, Liddle J, et al. Clinical placements in residential aged care facilities: the impact on nursing students' perception of aged care and the effect on career plans. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;23(4):14–9.

Duggan S, Mitchell EA, Moore KD. 'With a bit of tweaking.We could be great'. An exploratory study of the perceptions of students on working with older people in a preregistration BSc (Hons) nursing course. Int J Older People Nursing. 2013;8(3):207–15.

Jefferson AL, Cantwell NG, Byerly LK, Morhardt D. Medical student education program in Alzheimer's disease: the PAIRS program. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:80.

Koehler AR, Davies S, Smith LR, Hooks T, Schanke H, Loeffler A, et al. Impact of a stand-alone course in gerontological nursing on undergraduate nursing students' perceptions of working with older adults: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;46:17–23.

Fox SD, Wold JE. Baccalaureate student gerontological nursing experiences: raising consciousness levels and affecting attitudes. J Nurs Educ. 1996;35(8):348–55.

Herdman E. Challenging the discourses of nursing ageism. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(1):105–14.

Bagri AS, Tiberius R. Medical student perspectives on geriatrics and geriatric education. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1994–9.

Carlson E. Meaningful and enjoyable or boring and depressing? The reasons student nurses give for and against a career in aged care. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(3–4):602–4.

Samra R. Medical students; and doctors attitudes toward older patients and their care: what do we known and where do we go from here? 2013;Ph.D.:N.PAG p-N.PAG p.

Kloster T, Høie M, Skår R. Nursing students' career preferences: a Norwegian study. J Adv Nurs. 2007;59(2):155–62.

Swanlund S, Kujath A. Attitudes of baccalaureate nursing students toward older adults: a pilot study. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2012;33(3):181–3.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Happell B. The role of nursing education in the perpetuation of inequality. Nurse Educ Today. 2002;22(8):632–40.

Meiboom AA, Diedrich C, Vries HD, Hertogh C, Scheele F. The hidden curriculum of the medical care for elderly patients in medical education: a qualitative study. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2015;36(1):30–44.

Norredam M, Album D. Prestige and its significance for medical specialties and diseases. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(6):655–61.

Album D, Westin S. Do diseases have a prestige hierarchy? A survey among physicians and medical students. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):182–8.

Tullo E, Allan L. What should we be teaching medical students about dementia? Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(7):1044–50.

Banerjee S, Farina N, Daley S, Grosvenor W, Hughes L, Hebditch M, et al. How do we enhance undergraduate healthcare education in dementia? A review of the role of innovative approaches and development of the time for dementia Programme. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(1):68–75.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Nicolas Farina, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, for guidance during the review process.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of a PhD studentship part funded by Health Education England, working across Kent, Surrey and Sussex. Health Education England had no role in the design or completion of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: MH, SD, SB, JW; screening: MH, JS, SD; data abstraction: MH, JS, GS, SD. Data synthesis: MH, SD; manuscript drafting: MH, SD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Example Search. Example search terms: CINAHL 20/09/2019.

Additional file 2.

Extraction Template. Data extraction form.

Additional file 3.

Overview of Studies. Details of each included study.

Additional file 4.

Summary of Factors. Overview of the factors resulting from the synthesis and supporting studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hebditch, M., Daley, S., Wright, J. et al. Preferences of nursing and medical students for working with older adults and people with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ 20, 92 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02000-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02000-z