Abstract

Background

Little is known about the heterogeneous clinical profile of physical frailty and its association with cognitive impairment in older U.S. nursing home (NH) residents.

Methods

Minimum Data Set 3.0 at admission was used to identify older adults newly-admitted to nursing homes with life expectancy ≥6 months and length of stay ≥100 days (n = 871,801). Latent class analysis was used to identify physical frailty subgroups, using FRAIL-NH items as indicators. The association between the identified physical frailty subgroups and cognitive impairment (measured by Brief Interview for Mental Status/Cognitive Performance Scale: none/mild; moderate; severe), adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics, was estimated by multinomial logistic regression and presented in adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

In older nursing home residents at admission, three physical frailty subgroups were identified: “mild physical frailty” (prevalence: 7.6%), “moderate physical frailty” (44.5%) and “severe physical frailty” (47.9%). Those in “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” had high probabilities of needing assistance in transferring between locations and inability to walk in a room. Residents in “severe physical frailty” also had greater probability of bowel incontinence. Compared to those with none/mild cognitive impairment, older residents with moderate or severe impairment had slightly higher odds of belonging to “moderate physical frailty” [aOR (95%CI)moderate cognitive impairment: 1.01 (0.99–1.03); aOR (95%CI)severe cognitive impairment: 1.03 (1.01–1.05)] and much higher odds to the “severe physical frailty” subgroup [aOR (95%CI)moderate cognitive impairment: 2.41 (2.35–2.47); aOR (95%CI)severe cognitive impairment: 5.74 (5.58–5.90)].

Conclusions

Findings indicate the heterogeneous presentations of physical frailty in older nursing home residents and additional evidence on the interrelationship between physical frailty and cognitive impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 1.2 million U.S. older adults aged ≥65 years reside in a nursing home (NH) [1]. Physical frailty, characterized by decreased physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to exogenous stressors [2], and cognitive impairment, ranging from mild cognitive impairment to fully-developed dementia [3], are the two most prominent conditions in this population. Both are highly prevalent, with 30–85% of older nursing home residents experiencing physical frailty [4,5,6] and 65% moderate to severe cognitive impairment [1]. Both are associated with adverse health outcomes, including lowered quality of life and elevated risks for hospitalization and mortality [4, 7,8,Supplement Method). Because the subgroups of physical frailty did not vary across cognitive impairment levels, we included cognitive impairment as a covariate [41] to assess its association with the identified physical frailty subgroups using multinomial logistic model, adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics. Results were presented in adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

Sensitivity analysis

Consistent with the “cognitive frailty” concept by IANA and IAGG, we conducted three sets of sensitivity analysis by (A) excluding older residents with diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (n = 767,034); (B) excluding older residents with diagnosis of non- Alzheimer’s/other dementia (n = 529,832); (C) excluding older residents with diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and those with non- Alzheimer’s/other dementia (n = 460,612). In each subsample, LCA models were fit to identify the physical frailty subgroup, and the association between cognitive impairment and the identified subgroups were assessed following the same steps as the main analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

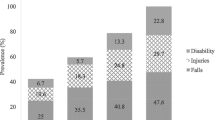

As shown in Table 1, of the 871,801 newly-admitted older residents, 44.3% were ≥ 85 years old, 65.3% women, and 18.8% racial/ethnic minority. Approximately three quarters of residents entered urban nursing homes. Nearly two-thirds were admitted from acute hospitals and less than one in five from the community. At admission, nearly two thirds of residents were physically frail, one in four was pre-frail, and over a third had severe cognitive impairment. About 45% of older residents had more than two physician-documented active diagnoses. Two in five reported presence of pain. Receipt of antidepressants (43.9%), antipsychotics (19.2%) and antianxiety medications (18.4%) were common.

Indicators of physical frailty

Of all residents, 62.1% did not experience fatigue, 91.5% needed physical assistance to transfer between surfaces, 85.7% could not walk between locations in a room, 57.5% experienced bowel incontinence, 3.0% lost at least 5% of weight in the past 3 months or 10% of weight in the past 6 months, 67.8% were on a regular diet, and 95.2% needed help with dressing. Similar distributions were observed across cognitive impairment level except for a few items. For older adults with severe cognitive impairment, there were higher proportions who did not experience fatigue, had bowel incontinence, and needed mechanically altered diet (Table 2).

Subgroups of physical frailty

For model selection, although entropy favored the 2-subgroup model, a clinically relevant subgroup emerged in the 3-subgroup model based on the item response probabilities. While AIC/BIC/adjusted BIC values favored models with more subgroups, for models with 4–6 subgroups, at least two of the identified subgroups largely overlapped and lacked sufficient separation. With these considerations, we chose the 3-subgroup model to represent physical frailty subgroups in nursing home residents at admission (Supplement Table S.2).

Based on the item-response probabilities, we assigned qualitative labels to the three subgroups: “mild physical frailty”, “moderate physical frailty” and “severe physical frailty”. (Table 3) About 7.6% of older residents had higher probabilities to belong to the “mild physical frailty” subgroup, 44.5% to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup, and 47.9% to the “severe physical frailty” subgroup. The major difference between the “mild physical frailty” subgroup and the other two subgroups were reflected in the probabilities for resistance and ambulation: older adults that were likely to be in the “moderate physical frailty” or the “severe physical frailty” subgroups had high probabilities of needing physical assistance to transfer between locations and inability to walk in a room. The “moderate physical frailty” subgroup and the “severe physical frailty” subgroup were mainly distinguished by the item-response probability for the incontinence item: residents belonging to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup had about an equal probability of having no urinary incontinence, urinary incontinence only, or urinary and bowel incontinence, while the “severe physical frailty” subgroup had a high probability of both urinary and bowel incontinence.

In sensitivity analysis when older residents with Alzheimer’s disease and/or those with non-Alzheimer’s/other dementia were excluded, the three-subgroup model appeared to best fit all three subpopulations (Supplement Table S.3). The overall patterns of the item-response probabilities and the respective prevalence of the physical frailty subgroups were similar and consistent with the full sample: “mild physical frailty” (prevalence range: 6.4–7.2%), “moderate physical frailty” (45.0–47.4%), and “severe physical frailty” (46.1–47.7%) (Supplement Table S.4).

Association between physical frailty subgroups and cognitive impairment

The three subgroups appeared consistent across cognitive impairment levels (Supplement Table S.5 and S.6). Cognitive impairment was thus included as a covariate in the 3-subgroup LCA model to examine its association with physical frailty subgroups, with the “mild physical frailty” subgroup as the reference, adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 4).

Compared to those with none/mild cognitive impairment, older residents with moderate impairment had similar odds to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup (aOR: 1.01, 95%: 0.99–1.03), while over twice as likely (aOR: 2.41, 95%CI: 2.35–2.47) to belong to the “severe physical frailty” subgroup; older residents with severe impairment had slightly higher odds to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup (aOR: 1.03, 95%CI: 1.01–1.05), and were close to 6 times as likely (aOR: 5.74; 95%CI: 5.58–5.90) to belong to the “severe physical frailty” subgroup.

For demographic and clinical characteristics, older age and being female were associated with higher odds of belonging to the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups, compared to their respective counterparts. Older residents who were racial/ethnic minorities were less likely to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup, but more likely to belong to the “severe physical frailty” subgroup. Older residents in rural nursing homes were less likely to be in the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups than those in urban nursing homes. Older residents admitted from acute hospitals had much higher probabilities of belonging to the “moderate physical frailty” and “severe physical frailty” subgroup than those admitted from the community.

Older residents with cancer, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular accident/TIA/stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, seizure disorder/epilepsy, hip fracture, other facture, or depression had higher odds of belong to the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups, while those with anxiety disorder had lower odds. Older residents with hypertension, arthritis or osteoporosis were more likely to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup, but less likely to be in the “severe physical frailty” subgroup. Older residents with any pain presence at admission were more likely to be in the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups. Older residents who received antipsychotics were less likely to be in the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups, while those who received antianxiety medications or antidepressants were more likely to do so.

Findings from sensitivity analysis suggested consistent positive association between cognitive impairment and physical frailty subgroups, but the magnitude of these associations increased (Supplement Table S.7). Particularly, in the absence of Alzheimer’s disease and non-Alzheimer’s/other dementia, older residents with severe cognitive impairment were 8.55 times (95% CI: 8.18–8.92) as likely to be in the “severe physical frailty” subgroup, compared to those with none/mild cognition.

Discussion

In older adults in U.S. nursing homes, we identified three subgroups of physical frailty at nursing home admission, namely, “mild physical frailty”, “moderate physical frailty” and “severe physical frailty”. Physical frailty subgroups did not appear to differ across cognitive impairment levels. Older residents with greater levels of cognitive impairment were more likely to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups. Recent research has shown the possibility to reduce the prevalence or even reverse the progress of physical frailty through physical activity programs, cognitive training, nutritional supplementation, and interventions individualized to older adults’ clinical conditions [12, 13, 42]. However, these studies were conducted in community-dwelling older adults. Whether physical frailty could also serve as an intervention target for older nursing home residents warrants further exploration. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide evidence for the heterogeneity of physical frailty in older nursing home residents and its association with cognitive impairment, which can inform the development of interventions tailored to specific clinical profiles of physical frailty and cognitive impairment, while also considering the potential impact from other demographic and clinical characteristics.

The majority of the older nursing home residents in this study had high probabilities of belonging to either “moderate physical frailty” or “severe physical frailty” subgroups. This was expected as nearly two-thirds of the older nursing home residents were admitted post-hospitalization, indicating a more clinically complex group with greater care needs. The use of LCA allowed us to examine the heterogeneity of physical frailty by identifying three distinct subgroups. Regardless of the subgroups they were more likely to belong to, all residents had a high probability of requiring assistance with dressing. Besides the high probabilities of limited mobility that older residents belonging to the “moderate physical frailty” subgroup or the “severe physical frailty” subgroup were shown to have, those in the “severe physical frailty” subgroup also had particularly greater probability of bowel incontinence. Such distinctive experiences would be masked when physical frailty is measured by categorizing a total score into robust/pre-frail/frail levels. Using the LCA person-centered approach, findings not only reflected the increasing levels of physical frailty severity, but also provided a more nuanced picture of the physical frailty experience in older nursing home residents.

We note one important caveat that the characteristics of the subgroups to be identified by LCA is determined by the observed indicators, namely, FRAIL-NH items in the context of this study. Unique experiences of physical frailty in older nursing home residents that were not captured by FRAIL-NH would not be reflected in the identified subgroups. Therefore, other distinct subgroups of physical frailty may exist in older nursing home residents and future studies should consider additional metrics to provide a more comprehensive picture of the heterogeneity of physical frailty in this population.

The finding that greater levels of cognitive impairment was associated with increasingly higher odds to be in the “moderate physical frailty” and “severe physical frailty” subgroups provides additional evidence on the frequent co-occurrence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment, which has been established in older adults in the community [43, 44], but not in nursing homes. Further, in the sensitivity analysis when older residents with Alzheimer’s disease and those with non-Alzheimer’s/other dementia were excluded, the magnitude of the association between cognitive impairment and the “severe physical frailty” subgroup substantially increased, which could be indicative of “cognitive frailty”.

Regardless of older residents’ cognitive impairment levels, the characteristics of the identified physical frailty subgroups appeared to be similar, without notable differences in the patterns of the item-response probabilities. The consistent patterns of physical frailty subgroups were also observed in sensitivity analysis. These findings should be interpreted in light of the potential limitation of the instruments used to measure physical frailty and cognitive impairment. Despite several validation studies [4, 27,28,29,30,55]. Given that MDS 3.0 only documenting the receipt of psychotropic medications in the past 7 days or since nursing home admission and the cross-sectional nature of the current study, we could not ascertain the clinical indications for these prescriptions and the length of time that the older adults have been using them, nor could we establish a causal relationship between psychotropic medications and physical frailty subgroups, explicitly, whether it was the concerns for physical frailty that influenced the prescription of these medications, or the use of these medications lead to a higher probability to belong to a certain physical frailty subgroup. However, considering that physical frailty may increase older adults’ vulnerability to adverse drug effects [52], additional research to examine their long-term impact on physical frailty could further inform the consideration of psychotropic medications in managing physical frailty in this population.

Limitations should be noted. Our analysis focused on older residents who stayed for longer than 100 days in nursing homes with life expectancy at admission longer than 6 months. If residents’ length of stay and/or life expectancy were differential with regards to symptoms of physical frailty, cognitive impairment levels, or other demographic and clinical characteristics, selection bias cannot be ruled out. This was a cross-sectional study at nursing home admission. As physical frailty and cognitive impairment could change during residents’ stay, longitudinal studies may be informative in exploring if and how physical frailty subgroups and cognitive impairment change over time.

Conclusions

In summary, three subgroups of physical frailty were identified in older U.S. nursing home residents at admission, and older residents with greater levels of cognitive impairment were increasingly more likely to belong to the “moderate physical frailty” and “severe physical frailty” subgroups. Findings have implications for future efforts to tailor interventions to specific symptom profiles of physical frailty and cognitive impairment and provide new evidence for the interrelationship between these two prominent conditions in older nursing home residents.

Availability of data and materials

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data (Minimum Data Set 3.0) under a data use agreement for this study. Minimum Data Set 3.0 is available from www.resdac.org with the permission of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Abbreviations

- IANA:

-

International Academy on Nutrition and Aging

- IAGG:

-

International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics

- LCA:

-

Latent class analysis

- MDS 3.0:

-

Minimum Data Set 3.0

- BIMS:

-

Brief Interview for Mental Status

- CPS:

-

Cognitive Performance Scale

- ID/DD facility:

-

Intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities facility

- TIA:

-

Transient ischemic attack

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Nursing home data compendium 2015. 2015.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11253156.

Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment—A review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):840–51 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23831959. [cited 2019 Feb 19].

Kaehr EW, Pape LC, Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. FRAIL-NH predicts outcomes in long term care. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(2):192–8 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26812516. [cited 2019 Feb 20].

Kanwar A, Singh M, Lennon R, Ghanta K, McNallan SM, Roger VL. Frailty and health-related quality of life among residents of long-term care facilities. J Aging Health. 2013;25(5):792–802 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23801154. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Yuan Y, Lapane KL, Tjia JT, Baek J, Liu S-H, Ulbricht CM. Physical frailty and cognitive impairment in older adults in United States nursing homes. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2021;50:60–67. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/515140. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Azzopardi RV, Vermeiren S, Gorus E, Habbig A-K, Petrovic M, Van Den Noortgate N, et al. Linking frailty instruments to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(11):1066.e1–1066.e11 Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1525861016303012. [cited 2019 May 6].

Hill NL, McDermott C, Mogle J, Munoz E, DePasquale N, Wion R, et al. Subjective cognitive impairment and quality of life: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(12):1965–77 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28829003. [cited 2019 Apr 21].

Zhang X, Dou Q, Zhang W, Wang C, **e X, Yang Y, et al. Frailty as a predictor of all-cause mortality among older nursing home residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019; 20(6): 657-663.e4. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861018306674?via%3Dihub. [cited 2019 Feb 24]

Liu LK, Guo CY, Lee WJ, Chen LY, Hwang AC, Lin MH, et al. Subtypes of physical frailty: Latent class analysis and associations with clinical characteristics and outcomes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46417 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28397814. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Xue Q-L, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, Zhou J, Fried LP. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(9):984–90 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18840805.

Lee PH, Lee YS, Chan DC. Interventions targeting geriatric frailty: a systemic review. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;3:47–52 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210833512000238. [cited 2019 Feb 24]. No longer published by Elsevier.

Apóstolo J, Cooke R, Bobrowicz-Campos E, Santana S, Marcucci M, Cano A, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent pre-frailty and frailty progression in older adults: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(1):140–232 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29324562. [cited 2019 Feb 18].

Ng TP, Feng L, Nyunt MSZ, Feng L, Niti M, Tan BY, et al. Nutritional, physical, cognitive, and combination interventions and frailty reversal among older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 2015;128(11):1225–1236.e1 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002934315005677. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Losa-Reyna J, Baltasar-Fernandez I, Alcazar J, Navarro-Cruz R, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Alegre LM, et al. Effect of a short multicomponent exercise intervention focused on muscle power in frail and pre frail elderly: a pilot trial. Exp Gerontol. 2019;115:114–21 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0531556518306776. [cited 2019 Feb 23].

Cadore EL, Casas-Herrero A, Zambom-Ferraresi F, Idoate F, Millor N, Gómez M, et al. Multicomponent exercises including muscle power training enhance muscle mass, power output, and functional outcomes in institutionalized frail nonagenarians. Age (Dordr). 2014;36(2):773–85 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24030238. [cited 2019 Mar 18].

Kidd T, Mold F, Jones C, Ream E, Grosvenor W, Sund-Levander M, et al. What are the most effective interventions to improve physical performance in pre-frail and frail adults? A systematic review of randomised control trials. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:184 Available from: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1196-x. [cited 2020 Aug 24]. BioMed Central Ltd.

Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Zambrano M, Sedler MJ. Influence of frailty on cognitive decline: a population-based cohort study in rural Ecuador. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(2):213–6 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861018305346. [cited 2019 Feb 23].

Mitnitski A, Fallah N, Rockwood K. A multistate model of cognitive dynamics in relation to frailty in older adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(7):507–16 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1047279711000275. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Auyeung TW, JSW L, Kwok T, Woo J. Physical frailty predicts future cognitive decline — A four-year prospective study in 2737 cognitively normal older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15(8):690–4 Available from: http://springer.longhoe.net/10.1007/s12603-011-0110-9. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Gross AL, Xue QL, Bandeen-Roche K, Fried LP, Varadhan R, McAdams-DeMarco MA, et al. Declines and impairment in executive function predict onset of physical frailty. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(12):1624–30 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27084314. [cited 2019 Mar 19].

Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, Abellan van Kan G, Ousset P-J, Gillette-Guyonnet S, et al. Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) International Consensus Group. J Nutr Health Aging. 2013;17(9):726–34 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24154642. [cited 2019 Apr 2].

Sargent L, Brown R. Assessing the current state of cognitive frailty: measurement properties. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(2):152–60 Available from: https://springer.longhoe.net/article/10.1007/s12603-016-0735-9. [cited 2020 Nov 17].

Panza F, Lozupone M, Solfrizzi V, Sardone R, Dibello V, Di Lena L, et al. Different cognitive frailty models and health- and cognitive-related outcomes in older age: from epidemiology to prevention. Perry G, Avila J, Tabaton M, Zhu X, editors. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):993–1012 Available from: http://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-170963. [cited 2019 Mar 13].

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument 3.0 user’s manual, version 1.14. 2016.

RTI International. MDS 3.0 quality measures user’s manual. 2017. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-Users-Manual-V11-Final.pdf. [cited 2019 Apr 14].

Luo H, Lum TYS, Wong GHY, Kwan JSK, Tang JYM, Chi I. Predicting adverse health outcomes in nursing homes: a 9-year longitudinal study and development of the FRAIL-Minimum Data Set (MDS) quick screening tool. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1042–7 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861015006064?via%3Dihub. [cited 2019 Mar 16].

Theou O, Tan ECK, Bell JS, Emery T, Robson L, Morley JE, et al. Frailty levels in residential aged care facilities measured using the frailty index and FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e207–12 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27783396. [cited 2019 Feb 19].

Theou O, Sluggett JK, Bell JS, Lalic S, Cooper T, Robson L, et al. Frailty, hospitalization, and mortality in residential aged care. J Gerontol Ser A. 2018;73(8):1090–6 Available from: https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article/73/8/1090/4372242. [cited 2019 Mar 13].

De Silva TR, Theou O, Vellas B, Cesari M, Visvanathan R. Frailty screening (FRAIL-NH) and mortality in French nursing homes: results from the incidence of pneumonia and related consequences in nursing home residents study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(5):411–4 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861017307879?via%3Dihub. [cited 2019 Mar 16].

Yang M, Zhuo Y, Hu X, **e L. Predictive validity of two frailty tools for mortality in Chinese nursing home residents: frailty index based on common laboratory tests (FI-Lab) versus FRAIL-NH. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(12):1445–52 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30259498. [cited 2019 Mar 16].

Buckinx F, Croisier J-L, Reginster J-Y, Lenaerts C, Brunois T, Rygaert X, et al. Prediction of the incidence of falls and deaths among elderly nursing home residents: the SENIOR study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(1):18–24 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861017303572?via%3Dihub. [cited 2019 Mar 16].

Si H, ** Y, Qiao X, Tian X, Liu X, Wang C. Comparing diagnostic properties of the FRAIL-NH scale and 4 frailty screening instruments among Chinese institutionalized older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(2):188–93 Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-019-1301-z. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Kaehr E, Visvanathan R, Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. Frailty in nursing homes: the FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(2):87–9 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25556303. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

Saliba D, Buchanan J, Edelen MO, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, et al. MDS 3.0: brief interview for mental status. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):611–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22796362. [cited 2019 Apr 6].

Morris JN, Fries BE, Mehr DR, Hawes C, Phillips C, Mor V, et al. MDS cognitive performance scale. J Gerontol. 1994;49(4):M174–82 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8014392.

Hartmaier SL, Sloane PD, Guess HA, Koch GG, Mitchell CM, Phillips CD. Validation of the minimum data set cognitive performance scale: agreement with the mini-mental state examination. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(2) Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7874589/. [cited 2021 Jan 27].

Paquay L, De Lepeleire J, Schoenmakers B, Ylieff M, Fontaine O, Buntinx F. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of the Cognitive Performance Scale (Minimum Data Set) and the Mini-Mental Scale Exam for the detection of cognitive impairment in nursing home residents. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(4):286–93 Available from: www.interrai.org. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

SAS Version 9.4. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 8th ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2017.

Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent class and latent transition analysis: with applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013.

von Haehling S, Bernabei R, Anker SD, Morley JE, Vandewoude MF, Rockwood K, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23764209. [cited 2019 Mar 18].

Rosado-Artalejo C, Carnicero JA, Losa-Reyna J, Guadalupe-Grau A, Castillo-Gallego C, Gutierrez-Avila G, et al. Cognitive performance across 3 frailty phenotypes: toledo study for healthy aging. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(9):785–90 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861017302232. [cited 2019 Feb 23].

Ávila-Funes JA, Amieva H, Barberger-Gateau P, Le Goff M, Raoux N, Ritchie K, et al. Cognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of the phenotype of frailty for adverse health outcomes: the three-city study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):453–61 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02136.x. [cited 2019 Mar 19].

Nakai Y, Makizako H, Kiyama R, Tomioka K, Taniguchi Y, Kubozono T, et al. Association between chronic pain and physical frailty in community-dwelling older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(8) Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31013877/. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, Simpkins S, Seymour MT, Selby PJ, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1091–101 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25403592/. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Vitale C, Spoletini I, Rosano GM. Frailty in heart failure: implications for management. Card Fail Rev. 2018;4(2):104. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6125710/. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Kong L-N, Lyu Q, Yao H-Y, Yang L, Chen S-Z. The prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling older adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;119:103952 Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34022743/. [cited 2021 Jun 10].

Mezuk B, Edwards L, Lohman M, Choi M, Lapane K. Depression and frailty in later life: a synthetic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(9):879–92 Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/gps.2807. [cited 2019 Aug 20].

Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Leurgans S, Bennett DA. Physical frailty in older persons is associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2008;71(7):499–504 Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC2676981/. [cited 2021 Feb 23].

Petermann-Rocha F, Lyall DM, Gray SR, Esteban-Cornejo I, Quinn TJ, Ho FK, et al. Associations between physical frailty and dementia incidence: a prospective study from UK Biobank. Lancet Heal Longev. 2020;1(2):e58–68 Available from: www.thelancet.com/. [cited 2021 Feb 23].

Porter B, Arthur A, Savva GM. How do potentially inappropriate medications and polypharmacy affect mortality in frail and non-frail cognitively impaired older adults? A cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5) Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6530304/?report=abstract. [cited 2020 Nov 4].

Stock KJ, Hogan DB, Lapane K, Amuah JE, Tyas SL, Bronskill SE, et al. Antipsychotic use and hospitalization among older assisted living residents: does risk vary by frailty status? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(7):779–90 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1064748117302087?via%3Dihub. [cited 2019 Feb 24].

An R, Lu L. Antidepressant use and functional limitations in U.S. older adults. J Psychosom Res. 2016;80:31–6 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399915300167. [cited 2019 Aug 28].

Mallery L, MacLeod T, Allen M, McLean-Veysey P, Rodney-Cail N, Bezanson E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of second-generation antidepressants for the treatment of older adults with depression: questionable benefit and considerations for frailty. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:306 Available from: https://bmcgeriatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12877-019-1327-4. [cited 2021 Feb 23]. BioMed Central.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1F99AG068591) and the National Institute of Mental Health (5R01MH117586).

The funders did not participate in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (YY, KL, TJ, JB, SL and CU) made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this study. YY made substantial contributions to the analysis, and KL, TJ, JB, SL, and CU to the interpretation of data. YY have drafted the manuscript, and all authors (YY, KL, TJ, JB, SL and CU) have substantively revised it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. This work was prepared while CU was employed at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board has approved this study. The study was considered exempt because it was a secondary data analysis using de-identified data (the Minimum Data Set 3.0) under a strict data use agreement with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Y., Lapane, K.L., Tjia, J. et al. Physical frailty and cognitive impairment in older nursing home residents: a latent class analysis. BMC Geriatr 21, 487 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02433-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02433-1