Abstract

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures are used to evaluate disease and treatments in many therapeutic areas, capturing relevant aspects of the disorder not obtainable through clinician or informant report, including those for which patients may have a greater level of awareness than those around them. Using PRO measures in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and prodromal Alzheimer's disease (AD) presents challenges given the presence of cognitive impairment and loss of insight. This overview presents issues relevant to the value of patient report with emphasis on the role of insight. Complex activities of daily living functioning and executive functioning emerge as areas of particular promise for obtaining patient self-report. The full promise of patient self-report has yet to be realized in MCI and prodromal AD, however, in part because of lack of PRO measures developed specifically for mild disease, limited use of best practices in new measure development, and limited attention to psychometric evaluation. Resolving different diagnostic definitions and improving clinical understanding of MCI and prodromal AD will also be critical to the development and use of PRO measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures are used to evaluate the impact of disease and treatment in many therapeutic areas. Among the advantages of patient report is the potential to capture aspects of the disease and treatment experience uniquely accessible to patients and, relatedly, to improve the measurement of therapeutic intervention effects [1]. The clinician's specialized framework of knowledge makes the clinician the most accurate reporter for some aspects of the disease experience. For which is the patient the more accurate reporter?

The most recent recommendations for core clinical criteria for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer's disease (AD) [2] note that despite 'preservation of independence in functional abilities' some impairment in complex functional tasks may be evident, such as higher error rate, taking longer, and/or being less efficient. The companion statement on research criteria for preclinical stages of AD [3] raises the possibility that biomarkers in combination with 'subjective assessment of subtle change will prove to be useful.' Subtle but potentially important features of the disease experience may be inaccessible to those other than the patient, raising the interesting possibility that the patient may have the most comprehensive and accurate knowledge of performance [4].

Although impairment in social or occupational functioning is part of AD diagnostic criteria [5], the place of functioning in diagnostic definitions of MCI is still evolving [2, 6–8]. Initial definitions of MCI were based on cognitive impairment and intact activities of daily living [9], but empirical data support the presence of functional deficits encompassing skills and activities beyond instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs), many of them subtle [10–15]. Functioning therefore emerges as an area of potential value for patient self-report. Two other areas with substantial prior research on patient self-report in AD and MCI are neuropsychiatric symptoms and health-related quality of life.

There are of course several important obstacles to use of patient self-report in cognitive impairment. Disease-related disruptions to memory and cognition may interfere with the ability to complete a questionnaire accurately, as might loss of insight with progressive disease [16], leading to reliance on informant and clinician report [15]. However, accuracy of informants, especially family caregivers, can also be suboptimal for multiple reasons, including the distortions introduced by caregiver depression and lack of caregiver awareness of some symptoms (for example, [17]).

The focus of this overview is on the value of patient report for evaluating disease course and treatments in MCI and in prodromal, or 'early' AD [18]. The emphasis is on early disease, corresponding to newer terminology referencing prodromal AD, as well as to the less specific 'mild cognitive impairment' referenced by Petersen and colleagues [9].

Methods and findings

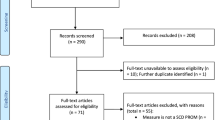

Domains important for patient report in cognition were identified based on literature reviews completed for the Cognition Initiative, now the Cognition Working Group of the Critical Path Institute, between August 2009 and January 2011. Initial searches were limited to the period from January 2004 to June 2009 with subsequent updates through March 2011. Functioning, variously defined, emerged as an important area for self-report in early disease. There has been recent PRO measure development and empirical studies in the areas of complex ADL functioning and neuropsychological aspects of functioning (for example, executive functioning); additional work in self-reported neuropsychiatric symptoms and health-related quality of life was also identified. Each of these areas is considered briefly below, followed by a discussion of the role of insight in patient self-report. Details of the search and literature review are available below. A summary of selected measures is presented in Table 1.

Search methods

The initial literature search strategy targeted publications on AD and MCI (specifically 'AD, moderate to severe' and 'MCI or very early AD'), crossing this literature with specific domain terms (functioning, functional status, executive functioning, HRQL, affect/mood/behavior). The search was limited to English language publications from 2004 to 2009 in MedLine and Embase. To ensure that relevant measures used in clinical trials for currently marketed AD drugs were included, separate searches were conducted for MCI and AD in each domain of interest, limited to 1999 to 2009, with the main focus on 'Alzheimer's disease' OR 'mild cognitive impairment' OR 'cognitive impairment no dementia.' Since treatment efficacy was not the focus of this review, but rather measures used to assess efficacy and effectiveness from the perspective of patients and caregivers, this part of the search was limited to review articles. Searches were conducted in PubMed initially, followed by Medline, Cochrane Library of Systematic Reviews, PsychINFO, and Embase.

Full articles were retrieved if information on measure development, psychometric evaluation, and/or use were mentioned in the abstract. Information from retrieved articles was abstracted into tables addressing each of these elements. All relevant titles and abstracts were screened (level 1). Full papers were obtained for any studies considered potentially eligible or where uncertainty existed as to whether a paper should be included in the review. Full papers were formally assessed for relevance (level 2). Level 1 and 2 reviews for the literature review conformed to pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria, including focus on early AD/MCI patients, and caregiver- and patient-reported outcomes were included. Electronic data extraction forms were completed by reviewers trained in the critical assessment of evidence. A third reviewer independently examined any inconsistencies in extracted data elements between extractors and missing data fields. Any discrepancies in extracted data were resolved by consensus and any disagreements were resolved by consulting with a third investigator, as necessary. The consensus version of the extracted data was subsequently exported to the evidence tables. The extracted data elements from each accepted study included study design and measures, instruments, and domains and items of interest.

Patient-reported outcome measurement by domain

Everyday functioning: complex activities of daily living

Definitions of 'functioning' vary but generally include both basic activities of daily living (for example, bathing, dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (for example, handling finances, cooking, phone use) [19–21], with the latter set widely used to assess MCI and prodromal AD [22–32]. The term 'everyday functioning' is used to indicate basic, instrumental, and complex or 'higher order' ADLs (for example, planning social functions; see, for example, [33]).

Consensus on the specific functional deficits that characterize MCI or prodromal AD has not been reached, especially since early definitions of MCI required the absence of functional deficits. The presence of MCI, as well as subtlety of functional deficits relative to AD, is now recognized [34].

Many AD functioning measures exist given the centrality of functioning to the expression of disease, but most are informant reported, including in: the Physical Self-Maintenance Scale [35–37]; the Blessed Dementia Scale [36–38]; the Dependence Scale in Alzheimer's Disease [39]; the Disability Assessment for Dementia Scale [40, 41]; the Interview for Deterioration in Daily Living Dementia [42, 43]; and the Progressive Deterioration Scale [44].

Like most measures of functioning used in AD, the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) was developed as an interview-based informant-reported measure of level of independence in specific tasks [45]. Subsequently, a version for use with MCI, the ADCS ADL-MCI, was developed with both informant- and patient-completed versions; item content includes complex and instrumental ADLs, such as handling finances, shop**, travel, and remembering appointments [46]. To meet the need for a brief in-home rated ADL measure, the Activities of Daily Living Prevention Instrument was developed by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Prevention Instrument Project, and is based in part on items from the ACDS ADL-MCI, the Functional Activities Questionnaire [47], and the Disability Assessment for Dementia Scale [46, 48–52]. There are both patient- and informant-rated versions; item content overlaps substantially with the ADCS ADL-MCI.

The ADCS Prevention Instrument Project also developed the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument, with patient-and informant-completed versions. Although intended as a screening tool, item content includes a range of everyday functioning, including social activities and work performance [41, 42, 51–54].

The Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cognitive Impairment (PROCOG) [14] measures the impact of MCI and early AD-associated cognitive impairment on multiple domains, including specific everyday functioning skills and social functioning. Similarly, the Perceived Deficits Questionnaire addresses a range of symptoms and functional impacts of memory loss based on patient self-report and has proven useful for signal detection in a treatment trial for MCI, although it was originally developed for use in multiple sclerosis [4]. The Perceived Deficits Questionnaire is an example of a measure of 'subjective memory complaints', most of which include cognition symptom report along with functioning (for example, Questionnaire d'auto-évaluation de la mémoire (QAM)/Self-Evaluation Complaint Questionnaire [55]; Self-Rating Scale of Memory Functions [56]).

A summary of some relevant measures is provided in Table 1. As noted by others, few published reports on functioning measures include psychometric performance [32], although for the measures with patient-reported versions, available test-retest reliability data and con-current or predictive validity data generally indicate good psychometric performance, providing some evidence of accurate measurement. Of note is that despite content overlap in existing measures, some domains are relatively under-represented, such as social functioning or functioning related to language skills - both areas for which patient report may be particularly well-suited.

The domain of functional status in cognitive disorders is one with a long history of scale development and use, and AD research is currently well-served by existing informant-reported scales for assessing moderate to severe disease. However, most item content fails to capture subtle deficits, and few patient-reported measures have been developed to date.

Some performance-based assessments address areas that could be promising for adaptation as self-rated measures, including financial capacity [57, 58], facial emotion processing [59], and route navigation [60]. Linking functioning to specific cognitive skills through these and other areas may expand clinical characterization of prodromal AD [61].

Because of limited use of qualitative data collection from patients in the measure development process, a step key to best practice in measure development [1], further refinement of 'functioning' measures may be warranted, including through identifying and measuring aspects of functioning most relevant to early disease, and establishing consensus on the definition of everyday functioning and complex ADL functioning.

Executive functioning

Executive functioning represents the cognitive skills required for the planning, initiation, sequencing, and monitoring of complex goal-directed behavior, such as household chores [5, 62, 63]. Executive functioning impairment is a criterion for dementia diagnosis [6].

Executive functioning skills underlie the everyday functioning skills discussed above, but are considered separately here because measures of executive functioning focus on a specifically defined set of cognitive skills rather than on the tasks those skills enable. Data from Farias and colleagues [64, 65] support distinguishing between measurement of daily living skills and measurement of neuropsychological functioning, based on data showing a moderate correlation between measures of each in a sample with AD (see also [66]). More recently, data from the Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly (ACTIVE) Cognitive Intervention Trial also support this distinction, as well as the relationship between cognitive skills and everyday functioning [67].

Executive functioning measures that have been used in MCI include the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Adult version [68] (BRIEF-A [69]) and the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale [70, 71], with patient-and informant-reported versions for each. The BRIEF is a measure of everyday behavioral manifestations of executive control and is sensitive to subtle changes in MCI patients and those with cognitive complaints [68, 72]. Similar to findings from Farias and colleagues [65], BRIEF-A scores were only modestly correlated to neuropsychological measures of executive functioning, suggesting that self- and informant report provides unique information about executive functioning relative to performance-based measures. The Frontal Systems Behavior Scale is a rating scale of apathy, disinhibition, and executive function and has demonstrated sensitivity to impairment in an MCI sample [70].

Measures of executive functioning show promise for detection of subtle deficits in MCI [70, 71]. As noted above for everyday functioning measures, obtaining structured input from patients in accordance with best practice for measure development may usefully expand the set of relevant impacts to measure and/or aid with identifying differential importance of content from the patient perspective and by stage of disease.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

Although neuropsychiatric symptoms are frequently an important part of the disease course of AD, their presence earlier in the disease is not as well-established. In recognition of the unique presentation and possible prognostic significance of major depressive disorder within AD, the National Institute of Mental Health developed a modified provisional set of criteria for depression in AD, distinct from the DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition) criteria for major depressive disorder [73, 74]. Work with these criteria has indicated that the prevalence of major depressive disorder is significantly under-estimated in this population relative to DSM-IV-based prevalence estimates [74, 75].

Behavioral and psychological symptoms are evident among some MCI and mild AD patients [11], and at elevated rates relative to the normal aging population [76]. Increased apathy and executive dysfunction have been documented in MCI [70, 77]. There is preliminary evidence for higher rates of neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, agitation, disinhibition, irritability, and sleep problems among those with executive dysfunction type MCI relative to both amnestic and non-amnestic MCI [76] and presence of depression (based on caregiver report) has been found to be predictive of progression from amnestic MCI to AD [75].

Few measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms have self-report versions and few are validated for use in early disease. Further research is required to develop evidence for the validity of patient self-report for these symptoms.

Health-related quality of life

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) is the subjective assessment of an individual's psychological, physical and social functioning or well-being [78, 79] and is traditionally measured via self-report, although for AD, measures have both patient- and informant reported versions [80, 81]. No MCI-specific HRQL scale exists; instead, existing AD measures have been used in MCI (for example, the Alzheimer's Disease Related Quality of Life instrument [82]) as have generic measures (defined as measures intended for use with any population or therapeutic area; examples are the World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire, short version [83] and Short-Form (SF)-12 [84]). A systematic review of clinical trials in AD found very low use of HRQL measures (in <5% for trials conducted through part of 2006) [85]. Data from a small sample suggest that reliability and validity of HRQL self-report in MCI and AD is correlated with insight level [86]. While HRQL measures have been central to the rise of PRO assessment over the past two decades, the value of disease-specific HRQL assessment to treatment evaluation in MCI and prodromal AD is limited by lack of consensus on domains to include and lack of clarity about how to weight domains for scoring. The HRQL impact of MCI, distinct from that of later disease, remains to be defined. Further work exploring the relationship of HRQL to functioning, neuropsychological disease effects, and neuropsychiatric symptoms would enhance the quality of HRQL measurement and improve its usefulness for research applications.

Insight and patient self-report

Insight into illness is a critical issue for patient self-report in MCI and AD given that insight into disease effects declines as the disease progresses [87–91]. Lack of insight is defined as lack of the ability to elaborate on the experience of a disease, label the symptoms of the disease as pathological, or have knowledge of the deeper effects that the symptoms or disease will have on one's environment [92]. Anosognosia is defined as unawareness of deficits, specific cognitive dysfunction, and lack of insight [16, 93–96]. The terms 'lack of insight' and 'anosognosia' are used largely interchangeably in the cognitive impairment literature.

The relationship of insight to progression in MCI is less clear than it is for AD. For a review of insight in MCI see [95]. There is currently no consensus on the best method to measure insight. Most methods rely on informant report as a 'gold standard' with patient/informant concordance taken as an indirect measure of patient insight. When the informant is the caregiver, accuracy of report bears critical examination. Caregiver burden, level of depression and anxiety, and caregiver health, including cognitive health, may influence accuracy of caregiver report (for example, [97, 98]).

Within the AD literature, there has been examination of concordance along with caregiver factors in reporting [17, 86, 99, 100]. Data on patient/informant concordance and informant accuracy are limited for the milder levels of cognitive impairment. In general, data support an inverse correlation between insight and severity of cognitive impairment and an inverse correlation between patient and caregiver report and severity of cognitive impairment [88, 101, 102]. Dementia patients likely underestimate their deficits in comparison to caregiver informants [103], with concordance further reduced as disease progresses (for example, [104]).

Some empirical reports conclude MCI patients have preserved insight. For example, Farias and colleagues [15] found that MCI patient self-report was concordant with reports of others, suggesting that MCI patients do not under-report actual deficits in cognition and functioning. Other studies suggest lack of MCI patient insight (see [95] for a review). Conflicting findings about insight and ability of patients to self-report may be due to different definitions of insight, different definitions of MCI, and/or different methods of measuring insight. Most studies of insight focus on insight for memory functioning; few studies address insight for other cognitive skills, everyday functional abilities, behavior, or affect [95]. The current literature on insight in MCI is limited by lack of specificity about domains affected, a critical point given evidence of differential insight by domain for MCI patients [91, 105–107]. Insight may be well-preserved in some domains across a range of disease severity, but may diminish more rapidly in others [95]. For example, Clement and colleagues [91] found that some but not all domains assessed corresponded to performance deficits in global cognitive score and executive functioning for MCI patients, suggesting MCI patients may be aware of general cognitive deficits but not specific memory deficits. To date, the literature on MCI supports the conclusion that insight in MCI is not a single construct and that insight might be spared for some but impaired for other domains (see Roberts and colleagues [95] for a review).

Evidence suggests that MCI patients may have knowledge of deficits in advance of when deficits are clinically discernible [108–110]. Kalbe and colleagues [93] found that MCI patients overestimate cognitive deficits relative to informants on a 13-domain complaint interview; mild AD patients underestimate their deficits relative to an informant. The validity of the conclusion of 'overestimation' is worth challenging, however, as early cognitive loss may be apparent to the patient but no one else, in part because of the nature of the deficits and in part because MCI patients may actively hide symptoms from others.

To optimize patient self-report, further research is warranted to determine the relationship of insight to level of disease severity, attending to potential differences in insight by domain rather than treating insight as a single global construct. It will be particularly interesting to identify those domains for which patients, especially MCI patients, may have the most accurate view of performance relative to other informants, including clinicians.

Some patient-reported insight scales are presented in Table 1.

Conclusion

The increasing interest in MCI due to AD [2], preclinical AD [111], and prodromal AD [18] presents an opportunity to advance outcomes measurement in cognitive disorders by addressing ceiling effects of existing measures and by expanding the range of measurement targets beyond neuropsychological assessments into the realm of patient-reported outcomes. Patient self-report also offers a means of expressing, and perhaps quantifying, the clinical significance of specific clinical changes.

Progress in identification of treatments for cognitive impairment depends on accurate measurement. Among the concepts for which patient self-report could be valuable, and for which measurement appears feasible based on available psychometric data, are aspects of everyday functioning and complex activities of daily living and some aspects of executive functioning. Few measures currently address these concepts. Further, domains included in existing measures vary and no measure is comprehensive; consensus on specific functioning domains relevant to early disease would improve measurement. The extent to which under-studied areas, such as social functioning and language skills, are useful to assess is uncertain given lack of data.

Subtle changes in mood and affect specific to MCI may be usefully captured by self-report but to date there are limited data on validity of patient self-report of neuropsychiatric symptoms in early disease. Measurement of the health-related quality of life impact of MCI has proceeded largely on the basis of measures developed for AD; relevance to the MCI experience remains to be established. Understanding the MCI experience in greater depth can improve conceptualization of HRQL. Currently, HRQL assessments in MCI and mild AD are based largely on existing AD measures with little psychometric performance data on suitability for measurement of milder levels of impairment.

Other domains may prove useful to explore for self-report. For example, cognitive impairment is often associated with somatic changes, including changes in eating behavior, such as dysphagia, along with weight loss, changes in olfaction, sleep quality, balance, and increased fall risk [112–119].

The impact of fluctuating or declining insight in mild cognitive impairment on patient report is unclear. At what point does loss of insight make patient self-report no longer reliable and valid? Current research suggests that this point may vary by domain, with patients demonstrating sufficient insight to reliably and validly self-report about disease-related impairment in some areas well into mild to moderate AD.

Consideration of strategies for quantifying the impact of other variables on the accuracy of measurement should be part of measure validation. Cultural differences in symptom expression and interpretation are one example. Item response theory methods will likely be of value to identifying differential item functioning and quantifying cultural confounds [120–122]. In addition to the possibilities of new measure development, such as is being undertaken by the Cognition Working Group of the Critical Path Institute's PRO Consortium, existing AD measures could be tested in the MCI population and converted to self-report if feasible.

The increasing emphasis of research on symptoms, correlates, and impact of cognitive impairment at mild levels suggests that the time is right for development of new patient-reported measures for MCI. Although measurement from the perspective of patients with MCI and prodromal AD is still at an early stage, the development of new measures and psychometric evaluation of existing AD measures for use in early disease should be pursued to increase the tools available and to expand our understanding of mild levels of cognitive impairment.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer's disease

- ADCS-ADL:

-

Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living

- ADL:

-

activities of daily living

- BRIEF-A:

-

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Adult version

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Fourth Edition

- HRQL:

-

health-related quality of life

- MCI:

-

mild cognitive impairment

- PRO:

-

patient-reported outcome.

References

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health: Guidance for Industry on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006, 4: 79-

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH: The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7: 270-279. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CR, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH: Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7: 280-292. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003.

Doody RS, Ferris SH, Salloway S, Sun Y, Goldman R, Watkins WE, Xu Y, Murthy AK: Donepezil treatment of patients with MCI: a 48-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2009, 72: 1555-1561. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000344650.95823.03.

American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. International Version with ICD-10 Codes. 1995, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 4

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, Delacourte A, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Jicha G, Meguro K, O'brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P: Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6: 734-746. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70178-3.

Hachinski V: Shifts in thinking about dementia. JAMA. 2008, 300: 2172-2173. 10.1001/jama.2008.525.

Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Bäckman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC: Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004, 256: 240-246. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x.

Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST: Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001, 56: 1133-1142.

Lu YF, Haase JE: Experience and perspectives of caregivers of spouse with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009, 6: 384-391. 10.2174/156720509788929309.

Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Aalten P, Starkstein S, Verhey FR, Yessavage J, Clement JP, Drapier D, Bayle F, Benoit M, Boyer P, Lorca PM, Thibaut F, Gauthier S, Grossberg G, Vellas B, Byrne J: Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer's disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2009, 24: 98-104. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.09.001.

Clare L, Rowlands J, Bruce E, Surr C, Downs M: 'I don't do like I used to do': a grounded theory approach to conceptualising awareness in people with moderate to severe dementia living in long-term care. Soc Sci Med. 2008, 66: 2366-2377. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.045.

Bennett HP, Piguet O, Grayson DA, Creasey H, Waite LM, Lye T, Corbett AJ, Hayes M, Broe GA, Halliday GM: Cognitive, extrapyramidal, and magnetic resonance imaging predictors of functional impairment in nondemented older community dwellers: the Sydney Older Person Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006, 54: 3-10. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00532.x.

Frank L, Flynn JA, Kleinman L, Margolis MK, Matza LS, Beck C, Bowman L: Validation of a new symptom impact questionnaire for mild to moderate cognitive impairment. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006, 18: 135-149. 10.1017/S1041610205002887.

Farias ST, Mungas D, Jagust W: Degree of discrepancy between self and other-reported everyday functioning by cognitive status: dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and healthy elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005, 20: 827-834. 10.1002/gps.1367.

Vogel A, Stokholm J, Gade A, Andersen BB, Hejl AM, Waldemar G: Awareness of deficits in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: do MCI patients have impaired insight?. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004, 17: 181-187. 10.1159/000076354.

Arguelles S, Loewenstein DA, Eisdorfer C, Arguelles T: Caregivers' judgments of the functional abilities of the Alzheimer's disease patient: impact of caregivers' depression and perceived burden. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2001, 14: 91-98. 10.1177/089198870101400209.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Cummings JL, Dekosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Delacourte A, Frisoni G, Fox NC, Galasko D, Gauthier S, Hampel H, Jicha GA, Meguro K, O'Brien J, Pasquier F, Robert P, Rossor M, Salloway S, Sarazin M, de Souza LC, Stern Y, Visser PJ, Scheltens P: Revising the definition of Alzheimer's disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9: 1118-1127. 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70223-4.

Benjamin Rose Hospital Staff: MULTIDISCIPLINARY studies of illness in aged persons; a new classification of functional status in activities of daily living. J Chronic Dis. 1959, 9 (1): 55-62. 10.1016/0021-9681(59)90137-7.

Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW: Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of Adl: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963, 185: 914-919. 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016.

Lawton MP, Brody EM: Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969, 9: 179-186. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179.

Leidy NK: Using functional status to assess treatment outcomes. Chest. 1994, 106: 1645-1646. 10.1378/chest.106.6.1645.

Arlt S, Lindner R, Rosler A, von Renteln-Kruse W: Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging. 2008, 25: 1033-1047. 10.2165/0002512-200825120-00005.

Aalten P, van Valen E, Clare L, Kenny G, Verhey F: Awareness in dementia: a review of clinical correlates. Aging Ment Health. 2005, 9: 414-422. 10.1080/13607860500143075.

Aupperle PM: Navigating patients and caregivers through the course of Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006, 67 (Suppl 3): 8-14. quiz 23

Birks J, Flicker L: Donepezil for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006, 3: CD006104-

Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, Takeda A, Picot J, Payne E, Clegg A: The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine for Alzheimer's disease. Health Technol Assess. 2006, 10: iii-iv. ix-xi, 1-160

Martinon-Torres G, Fioravanti M, Grimley EJ: Trazodone for agitation in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004, CD004990-4

Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods R, Verhey F, Chattat R, De Vugt M, Mountain G, O'Connell M, Harrison J, Vasse E, Dröes RM, Orrell M, INTERDEM group: A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health. 2008, 12: 14-29. 10.1080/13607860801919850.

Rabheru K: Disease staging and milestones. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007, 34 (Suppl 1): S62-66.

Scherder E, Dekker W, Eggermont L: Higher-level hand motor function in aging and (preclinical) dementia: its relationship with (instrumental) activities of daily life--a mini-review. Gerontology. 2008, 54: 333-341. 10.1159/000168203.

Sikkes SA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Pijnenburg YA, Scheltens P, Uitdehaag BM: A systematic review of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales in dementia: room for improvement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009, 80: 7-12. 10.1136/jnnp.2008.155838.

Ball K, Berch DB, Helmers KF, Jobe JB, Leveck MD, Marsiske M, Morris JN, Rebok GW, Smith DM, Tennstedt SL, Unverzagt FW, Willis SL, Advanced Cognitive Training for Independent and Vital Elderly Study Group: Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002, 288: 2271-2281. 10.1001/jama.288.18.2271.

Burton CL, Strauss E, Bunce D, Hunter MA, Hultsch DF: Functional abilities in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Gerontology. 2009, 55: 570-581. 10.1159/000228918.

Cidboy EL: Significance of behavioral pathology on functional performance in individuals with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2004, 19: 279-289. 10.1177/153331750401900505.

Demers L, Oremus M, Perrault A, Champoux N, Wolfson C: Review of outcome measurement instruments in Alzheimer's disease drug trials: psychometric properties of functional and quality of life scales. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000, 13: 170-180. 10.1177/089198870001300402.

Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M: The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects. Br J Psychiatry. 1968, 114: 797-811. 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797.

Erkinjuntti T, Hokkanen L, Sulkava R, Palo J: The blessed dementia scale as a screening test for dementia. Int J Geratr Psychiatry. 1988, 3: 267-273. 10.1002/gps.930030406.

Stern Y, Albert SM, Sano M, Richards M, Miller L, Folstein M, Albert M, Bylsma FW, Lafleche G: Assessing patient dependence in Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol. 1994, 49: M216-222.

Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S: Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer's disease: the disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther. 1999, 53: 471-481.

Gelinas I, Gauthier L, McIntyre M, Gauthier S: Development of a functional measure for persons with Alzheimer's disease: the disability assessment for dementia. Am J Occup Ther. 1999, 53 (5): 471-481.

Teunisse S, Derix MM: The interview for deterioration in daily living activities in dementia: agreement between primary and secondary caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997, 9 (Suppl 1): 155-162.

Teunisse S, Derix MM, van Crevel H: Assessing the severity of dementia. Patient and caregiver. Arch Neurol. 1991, 48: 274-277. 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530150042015.

DeJong R, Osterlund OW, Roy GW: Measurement of quality-of-life changes in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Clin Ther. 1989, 11: 545-554.

Galasko D, Bennett D, Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas R, Grundman M, Ferris S: An inventory to assess activities of daily living for clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease. The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997, 11 (Suppl 2): S33-39.

Galasko D, Bennett DA, Sano M, Marson D, Kaye J, Edland SD: ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: assessment of instrumental activities of daily living for community-dwelling elderly individuals in dementia prevention clinical trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006, 20: S152-169. 10.1097/01.wad.0000213873.25053.2b.

Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Chance JM, Filos S: Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982, 37: 323-329.

Cummings JL, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Salmon D, Ferris SH: ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: behavioral measures in primary prevention trials. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006, 20: S147-151. 10.1097/01.wad.0000213872.17429.0f.

Ferris SH, Aisen PS, Cummings J, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Schneider L, Sano M, Whitehouse PJ, Edland S, Thal LJ: ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: overview and initial results. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006, 20: S109-123. 10.1097/01.wad.0000213870.40300.21.

Patterson MB, Whitehouse PJ, Edland SD, Sami SA, Sano M, Smyth K, Weiner MF: ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: quality of life assessment (QOL). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006, 20: S179-190. 10.1097/01.wad.0000213874.25053.e5.

Feldman H, Sauter A, Donald A, Gelinas I, Gauthier S, Torfs K, Parys W, Mehnert A: The disability assessment for dementia scale: a 12-month study of functional ability in mild to moderate severity Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001, 15: 89-95. 10.1097/00002093-200104000-00008.

Gelinas I, Gauthier S, Cyrus PA: Metrifonate enhances the ability of Alzheimer's disease patients to initiate, organize, and execute instrumental and basic activities of daily living. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000, 13: 9-16. 10.1177/089198870001300102.

Behl P, Lanctot KL, Streiner DL, Guimont I, Black SE: Cholinesterase inhibitors slow decline in executive functions, rather than memory, in Alzheimer's disease: a 1-year observational study in the Sunnybrook dementia cohort. Curr Alzheiner Res. 2006, 3 (2): 147-156. 10.2174/156720506776383031.

Walsh SP, Raman R, Jones KB, Aisen PS: ADCS Prevention Instrument Project: the Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument (MCFSI). Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006, 20: S170-178. 10.1097/01.wad.0000213879.55547.57.

Perrotin A, Belleville S, Isingrini M: Metamemory monitoring in mild cognitive impairment: Evidence of a less accurate episodic feeling-of-knowing. Neuropsychologia. 2007, 45: 2811-2826. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.003.

Michon A, Deweer B, Pillon B, Agid Y, Dubois B: Relation of anosognosia to frontal lobe dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994, 57: 805-809. 10.1136/jnnp.57.7.805.

Griffith HR, Belue K, Sicola A, Krzywanski S, Zamrini E, Harrell L, Marson DC: Impaired financial abilities in mild cognitive impairment: a direct assessment approach. Neurology. 2003, 60: 449-457.

Marson DC, Sawrie SM, Snyder S, McInturff B, Stalvey T, Boothe A, Aldridge T, Chatterjee A, Harrell LE: Assessing financial capacity in patients with Alzheimer disease: A conceptual model and prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 2000, 57: 877-884. 10.1001/archneur.57.6.877.

Teng E, Lu PH, Cummings JL: Deficits in facial emotion processing in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007, 23: 271-279. 10.1159/000100829.

DeIpolyi AR, Rankin KP, Mucke L, Miller BL, Gorno-Tempini ML: Spatial cognition and the human navigation network in AD and MCI. Neurology. 2007, 69: 986-997. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271376.19515.c6.

Okonkwo OC, Wadley VG, Griffith HR, Ball K, Marson DC: Cognitive correlates of financial abilities in mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006, 54: 1745-1750. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00916.x.

Duke LM, Kaszniak AW: Executive control functions in degenerative dementias: a comparative review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000, 10: 75-99. 10.1023/A:1009096603879.

Royall DR, Palmer R, Chiodo LK, Polk MJ: Declining executive control in normal aging predicts change in functional status: the Freedom House Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52: 346-352. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52104.x.

Farias ST, Mungas D, Reed BR, Cahn-Weiner D, Jagust W, Baynes K, Decarli C: The measurement of everyday cognition (ECog): scale development and psychometric properties. Neuropsychology. 2008, 22: 531-544.

Farias ST, Harrell E, Neumann C, Houtz A: The relationship between neuropsychological performance and daily functioning in individuals with Alzheimer's disease: ecological validity of neuropsychological tests. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003, 18: 655-672.

Cahn-Weiner DA, Ready RE, Malloy PF: Neuropsychological predictors of everyday memory and everyday functioning in patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003, 16: 84-89. 10.1177/0891988703016002004.

Gross AL, Rebok GW, Unverzagt FW, Willis SL, Brandt J: Cognitive predictors of everyday functioning in older adults: results from the ACTIVE Cognitive Intervention trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011, 66: 557-566.

Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L: Behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychol. 2000, 6: 235-238. 10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152.

Roth RM, Isquith PK, Gioia GA: Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Function - Adult Version. 2005, Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc

Ready RE, Ott BR, Grace J, Cahn-Weiner DA: Apathy and executive dysfunction in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003, 11: 222-228.

Grace J, Malloy P: Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe): Professional Manual. 2001, Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources

Rabin LA, Roth RM, Isquith PK, Wishart HA, Nutter-Upham KE, Pare N, Flashman LA, Saykin AJ: Self-and informant reports of executive function on the BRIEF-A in MCI and older adults with cognitive complaints. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2006, 21: 721-732. 10.1016/j.acn.2006.08.004.

Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Alexopoulos GS, Breitner JC, Bruce ML, Caine ED, Cummings JL, Devanand DP, Krishnan KR, Lyketsos CG, Lyness JM, Rabins PV, Reynolds CF, Rovner BW, Steffens DC, Tariot PN, Lebowitz BD: Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002, 10: 125-128.

Teng E, Ringman JM, Ross LK, Mulnard RA, Dick MB, Bartzokis G, Davies HD, Galasko D, Hewett L, Mungas D, Reed BR, Schneider LS, Segal-Gidan F, Yaffe K, Cummings JL, Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers of California-Depression in Alzheimer's Disease Investigators: Diagnosing depression in Alzheimer disease with the national institute of mental health provisional criteria. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 16: 469-477. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318165dbae.

Lu PH, Edland SD, Teng E, Tingus K, Petersen RC, Cummings JL: Donepezil delays progression to AD in MCI subjects with depressive symptoms. Neurology. 2009, 72: 2115-2121. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aa52d3.

van der Linde R, Stephan BC, Matthews FE, Brayne C, Savva GM: Behavioural and psychological symptoms in the older population without dementia--relationship with socio-demographics, health and cognition. BMC Geriatr. 2010, 10: 87-10.1186/1471-2318-10-87.

Apostolova LG, Cummings JL: Neuropsychiatric manifestations in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of the literature. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008, 25: 115-126. 10.1159/000112509.

Schipper H, Clinch JJ, Olweny CL: Quality of Life Studies: Definitions and Conceptual Issues. 1996, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 2

Ware JE: Methodological Considerations in the Selection of Health Status Assessment Procedures. 1984, Greenwich, CT: La Jacq

Ettema TP, Droes RM, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW: A review of quality of life instruments used in dementia. Qual Life Res. 2005, 14: 675-686. 10.1007/s11136-004-1258-0.

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L: Quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Mental Health Aging. 1999, 5: 21-32.

Missotten P, Squelard G, Ylieff M, Di Notte D, Paquay L, De Lepeleire J, Fontaine O: Quality of life in older Belgian people: comparison between people with dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and controls. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 23: 1103-1109. 10.1002/gps.1981.

Muangpaisan W, Assantachai P, Intalapaporn S, Pisansalakij D: Quality of life of the community-based patients with mild cognitive impairment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2008, 8: 80-85. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00452.x.

Arlt S, Hornung J, Eichenlaub M, Jahn H, Bullinger M, Petersen C: The patient with dementia, the caregiver and the doctor: cognition, depression and quality of life from three perspectives. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008, 23: 604-610. 10.1002/gps.1946.

Scholzel-Dorenbos CJ, van der Steen MJ, Engels LK, Olde Rikkert MG: Assessment of quality of life as outcome in dementia and MCI intervention trials: a systematic review. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007, 21: 172-178. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df4c.

Berwig M, Leicht H, Gertz HJ: Critical evaluation of self-rated quality of life in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease--further evidence for the impact of anosognosia and global cognitive impairment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009, 13: 226-230. 10.1007/s12603-009-0063-4.

Mangone CA, Hier DB, Gorelick PB, Ganellen RJ, Langenberg P, Boarman R, Dollear WC: Impaired insight in Alzheimer's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991, 4: 189-193. 10.1177/089198879100400402.

McDaniel KD, Edland SD, Heyman A: Relationship between level of insight and severity of dementia in Alzheimer disease. CERAD Clinical Investigators. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995, 9: 101-104. 10.1097/00002093-199509020-00007.

Starkstein SE, Sabe L, Chemerinski E, Jason L, Leiguarda R: Two domains of anosognosia in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996, 61: 485-490. 10.1136/jnnp.61.5.485.

Arkin S, Mahendra N: Insight in Alzheimer's patients: results of a longitudinal study using three assessment methods. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2001, 16: 211-224. 10.1177/153331750101600401.

Clement F, Belleville S, Gauthier S: Cognitive complaint in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008, 14: 222-232.

Markova IS, Berrios GE: Insight into memory deficits. Memory Disorders in Psychiatric Practice. Edited by: Berrios GE, Hodges JR. 2000, New York: Cambridge University Press, 204-233.

Kalbe E, Salmon E, Perani D, Holthoff V, Sorbi S, Elsner A, Weisenbach S, Brand M, Lenz O, Kessler J, Luedecke S, Ortelli P, Herholz K: Anosognosia in very mild Alzheimer's disease but not in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005, 19: 349-356. 10.1159/000084704.

Ries ML, Jabbar BM, Schmitz TW, Trivedi MA, Gleason CE, Carlsson CM, Rowley HA, Asthana S, Johnson SC: Anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment: Relationship to activation of cortical midline structures involved in selfappraisal. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007, 13: 450-461.

Roberts JL, Clare L, Woods RT: Subjective memory complaints and awareness of memory functioning in mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009, 28: 95-109. 10.1159/000234911.

Cosentino S, Metcalfe J, Butterfield B, Stern Y: Objective metamemory testing captures awareness of deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Cortex. 2007, 43: 1004-1019. 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70697-X.

Dassel KB, Schmitt FA: The impact of caregiver executive skills on reports of patient functioning. Gerontologist. 2008, 48: 781-792. 10.1093/geront/48.6.781.

Mitchell M, Miller LS: Executive functioning and observed versus self reported measures of functional ability. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008, 22: 471-479. 10.1080/13854040701336436.

Wlodarczyk JH, Brodaty H, Hawthorne G: The relationship between quality of life, MMSE, and the IADL in patients with Alzheimer' s disease. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004, 39: 25-33. 10.1016/j.archger.2003.12.004.

Greenop KR, **ao J, Almeida OP, Flicker L, Beer C, Foster JK, van Bockxmeer FM, Lautenschlager NT: Awareness of cognitive deficits in older adults with cognitive-impairment-no-dementia (CIND): comparison with informant report. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011, 25: 24-33. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f81094.

Zanetti O, Vallotti B, Frisoni GB, Geroldi C, Bianchetti A, Pasqualetti P, Trabucchi M: Insight in dementia: when does it occur? Evidence for a nonlinear relationship between insight and cognitive status. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999, 54: P100-106.

Tremont G, Alosco ML: Relationship between cognition and awareness of deficit in mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011, 26: 299-306. 10.1002/gps.2529.

Ott BR, Lafleche G, Whelihan WM, Buongiorno GW, Albert MS, Fogel BS: Impaired awareness of deficits in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1996, 10: 68-76. 10.1097/00002093-199601020-00003.

Kleinman L, Frank L, Flynn JA, Matza L, Bowman L: Comparison of Informant and Neuropsychological Ratings of Cognitive Impairment. 2004, New York, NY: American Psychiatric Association

Okonkwo OC, Griffith HR, Vance DE, Marson DC, Ball KK, Wadley VG: Awareness of functional difficulties in mild cognitive impairment: a multidomain assessment approach. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57: 978-984. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02261.x.

Rankin KP, Baldwin E, Pace-Savitsky C, Kramer JH, Miller BL: Self awareness and personality change in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005, 76: 632-639. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.042879.

Banks S, Weintraub S: Self-awareness and self-monitoring of cognitive and behavioral deficits in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia and probable Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn. 2008, 67: 58-68. 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.11.004.

Cook S, Marsiske M: Subjective memory beliefs and cognitive performance in normal and mildly impaired older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2006, 10: 413-423. 10.1080/13607860600638487.

Reisberg B, Prichep L, Mosconi L, John ER, Glodzik-Sobanska L, Boksay I, Monteiro I, Torossian C, Vedvyas A, Ashraf N, Jamil IA, de Leon MJ: The premild cognitive impairment, subjective cognitive impairment stage of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2008, 4: S98-S108. 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.11.017.

Reisberg B, Gauthier S: Current evidence for subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) as the pre-mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage of subsequently manifest Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008, 20: 1-16.

Jack CR, Albert M, Knopman DS, McKhann GM, Sperling RA, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH: Introduction to revised criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011, 7: 257-262. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.004.

Cummings JL: Changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms as outcome measures in clinical trials with cholinergic therapies for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997, 11 (Suppl 4): S1-9.

Nourhashemi F, Vellas B: Weight loss as a predictor of dementia and Alzheimer's disease?. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008, 8: 691-693. 10.1586/14737175.8.5.691.

Gillette Guyonnet S, Abellan Van Kan G, Alix E, Andrieu S, Belmin J, Berrut G, Bonnefoy M, Brocker P, Constans T, Ferry M, Ghisolfi-Marque A, Girard L, Gonthier R, Guerin O, Hervy MP, Jouanny P, Laurain MC, Lechowski L, Nourhashemi F, Raynaud-Simon A, Ritz P, Roche J, Rolland Y, Salva T, Vellas B, International Academy on Nutrition and Aging Expert Group: IANA (International Academy on Nutrition and Aging) Expert Group: weight loss and Alzheimer's disease. J Nutr Health Aging. 2007, 11: 38-48.

Vellas B, Lauque S, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, Cortes F, Nourhashemi F, Cantet C, Ousset PJ, Grandjean H: Impact of nutritional status on the evolution of Alzheimer's disease and on response to acetylcholinesterase inhibitor treatment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005, 9: 75-80.

Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, Andrieu S, de Glisezinski I, Ousset PJ, Riviere D, Albarede JL, Vellas B: Weight loss in Alzheimer disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71: 637S-642S.

Chouinard J: Dysphagia in Alzheimer disease: a review. J Nutr Health Aging. 2000, 4: 214-217.

Priefer BA, Robbins J: Eating changes in mild-stage Alzheimer's disease: a pilot study. Dysphagia. 1997, 12: 212-221. 10.1007/PL00009539.

Djordjevic J, Jones-Gotman M, De Sousa K, Chertkow H: Olfaction in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008, 29: 693-706. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.11.014.

Fuh JL, Mega MS, Binetti G, Wang SJ, Magni E, Cummings JL: A transcultural study of agitation in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2002, 15: 171-174.

Chow TW, Liu CK, Fuh JL, Leung VP, Tai CT, Chen LW, Wang SJ, Chiu HF, Lam LC, Chen QL, Cummings JL: Neuropsychiatric symptoms of Alzheimer's disease differ in Chinese and American patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002, 17: 22-28. 10.1002/gps.509.

Reynish E, Cortes F, Andrieu S, Cantet C, Olde Rikkert M, Melis R, Froelich L, Frisoni GB, Jönsson L, Visser PJ, Ousset PJ, Vellas B, ICTUS Study Group: The ICTUS Study: A Prospective longitudinal observational study of 1,380 AD patients in Europe. Study design and baseline characteristics of the cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2007, 29: 29-38. 10.1159/000108915.

Pedrosa H, De Sa A, Guerreiro M, Maroco J, Simoes MR, Galasko D, de Mendonca A: Functional evaluation distinguishes MCI patients from healthy elderly people--the ADCS/MCI/ADL scale. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010, 14: 703-709. 10.1007/s12603-010-0102-1.

Sullivan MJL, Edgley K, Dehoux E: A survey of Multiple Sclerosis. Part I: Perceived cognitive problems and compensory stratey use. Can J Rehab. 1990, 4: 99-105.

Locke DE, Dassel KB, Hall G, Baxter LC, Woodruff BK, Hoffman Snyder C, Miller BL, Caselli RJ: Assessment of patient and caregiver experiences of dementia-related symptoms: development of the Multidimensional Assessment of Neurodegenerative Symptoms questionnaire. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009, 27: 260-272. 10.1159/000203890.

McNair D, Kahn R: Self assessment of cognitive deficits. Assessment in Geriatric Psychopharmacology. Edited by: Crook T, Ferris A, Baltus R. 1983, New Canaan, CT: Mark Powley, 137-143.

Spitznagel MB, Tremont G: Cognitive reserve and anosognosia in questionable and mild dementia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2005, 20: 505-515. 10.1016/j.acn.2004.11.003.

Hathaway SR, McKinley JC: A multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota): I. Construction of the schedule. J Psychology. 1940, 10: 249-254. 10.1080/00223980.1940.9917000.

Stout JC, Wyman MF, Johnson SA, Peavy GM, Salmon DP: Frontal behavioral syndromes and functional status in probable Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003, 11: 683-686.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this review was provided by the Cognition Working Group of Critical Path Institute's PRO Consortium. The pharmaceutical firms participating in the Cognition Working Group are: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. Critical Path Institute's PRO Consortium is supported by grant number U01FD003865 from the United States Food and Drug Administration and by Science Foundation Arizona under grant number SRG 0335-08. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments and feedback from the Cognition Working Group members on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The authors also thank Leah Kleinman, Jill Bell, and Anne Brooks for their assistance and review. The views expressed in this article are those of Dr Frank and do not necessarily reflect those of PCORI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

LF was a salaried employee of United BioSource Corporation (UBC) when some of the work included in this manuscript was completed. UBC held and still holds a contract with the Critical Path Institute for completion of work related to development of a new PRO measure and that work included literature reviews. Some content related to those literature reviews is included in this manuscript. During completion of this manuscript LF worked at MedImmune, LLC, owned by AstraZeneca, PLC, and served as an AstraZeneca industry sponsor representative to the Cognition Working Group of the Critical Path Institute. WRL holds stock in, and has a pension with, Pfizer. MC was an employee of Merck until 2010 and still holds stock, and has been a consultant with Critical Path Institute and the Cognition Working Group.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frank, L., Lenderking, W.R., Howard, K. et al. Patient self-report for evaluating mild cognitive impairment and prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alz Res Therapy 3, 35 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt97

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt97