Abstract

Background

Parasitic wasps constitute one of the largest group of venomous animals. Although some physiological effects of their venoms are well documented, relatively little is known at the molecular level on the protein composition of these secretions. To identify the majority of the venom proteins of the endoparasitoid wasp Chelonus inanitus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), we have randomly sequenced 2111 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from a cDNA library of venom gland. In parallel, proteins from pure venom were separated by gel electrophoresis and individually submitted to a nano-LC-MS/MS analysis allowing comparison of peptides and ESTs sequences.

Results

About 60% of sequenced ESTs encoded proteins whose presence in venom was attested by mass spectrometry. Most of the remaining ESTs corresponded to gene products likely involved in the transcriptional and translational machinery of venom gland cells. In addition, a small number of transcripts were found to encode proteins that share sequence similarity with well-known venom constituents of social hymenopteran species, such as hyaluronidase-like proteins and an Allergen-5 protein.

An overall number of 29 venom proteins could be identified through the combination of ESTs sequencing and proteomic analyses. The most highly redundant set of ESTs encoded a protein that shared sequence similarity with a venom protein of unknown function potentially specific of the Chelonus lineage. Venom components specific to C. inanitus included a C-type lectin domain containing protein, a chemosensory protein-like protein, a protein related to yellow-e3 and ten new proteins which shared no significant sequence similarity with known sequences. In addition, several venom proteins potentially able to interact with chitin were also identified including a chitinase, an imaginal disc growth factor-like protein and two putative mucin-like peritrophins.

Conclusions

The use of the combined approaches has allowed to discriminate between cellular and truly venom proteins. The venom of C. inanitus appears as a mixture of conserved venom components and of potentially lineage-specific proteins. These new molecular data enrich our knowledge on parasitoid venoms and more generally, might contribute to a better understanding of the evolution and functional diversity of venom proteins within Hymenoptera.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hymenopteran venoms have been intensively studied in social species such as bees, bumblebees, wasps, hornets and ants [1–6]. Most of the major allergens have been identified in species of medical importance through a combination of transcriptomic, proteomic, peptidomic and glycomic techniques recently gathered under the newly proposed term of venomic approaches [7]. In comparison, little has been done on the venom composition of parasitoid Hymenoptera although they represent more than 75% of described hymenopteran species and 10-20% of all insect species [8]. Fundamental benefits expected from venomic approaches applied to parasitic wasp venoms would consist, for example, in the discrimination between cellular transcripts present in the venom glands and those encoding true venom proteins, through the proteomic analysis of venom fluid. Moreover comprehensive analyses would allow a deeper characterization of weakly expressed venom components and a comparative work aiming at retracing the evolutionary history of hymenopteran venoms. Parasitoid venom proteins also constitute an underestimated source of toxins that could be studied for a variety of applied uses.

Parasitic wasps constitute by far the largest group of parasitic insects with an estimated total number of species of approximately 250 000 [9]. Some develop outside (ectoparasitoids) and others inside (endoparasitoids) the body of an insect or other arthropod host and, depending on the species, various stages of the host can be parasitized (egg, egg-larval, larval, pupal and adult parasitoids). In ectoparasitoid species, venoms often induce paralysis and/or regulate host development, metabolism and immune responses [10–12]. Venom proteins from endoparasitic wasps are predominately involved in regulation of host physiology and immune responses alone or in combination with other factors of maternal origin such as polydnaviruses (PDVs) or virus-like particles present in the venom itself or produced in the ovaries and ovarian fluids [13–17]. For example, venoms can synergize the effects of PDVs [18, 19] and can interfere with host's humoral [20–22] and cellular immune components [23–26].

To date, less than 50 proteins have been individually identified and characterized from the venoms of a restricted number of parasitoid wasps species [15, 27]. Broader studies have also previously investigated the composition of parasitoid venoms by the separate use of proteomic or transcriptomic approaches combined with bioinformatic analyses. A recent analysis of the venom proteome of the pupal ectoparasitoid wasp Nasonia vitripennis has been published, that benefited from the sequencing and annotation of this wasp genome [28]. Twelve venom proteins from the endoparasitoid Pteromalus puparum were also identified recently using a proteomic approach [29]. On the other hand, transcriptome analyses allowed the identification of venom proteins in the pupal endoparasitoid Pimpla hypochondriaca[30–32] and in two adult endoparasitoid species of the genus Microctonus[33]. Although these works are undoubtedly of great interest, most of them did not provide absolute evidence that all identified proteins were venom components. Therefore, there is still a crucial need for extensive analyses by combining various techniques of investigation at the molecular level to allow comparisons between species.

Chelonus inanitus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) is original among the parasitoid species currently studied in being an egg-larval endoparasitoid species. Indeed it oviposits into the eggs of its host, Spodoptera littoralis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and the parasitoid larva then develops inside the host embryo and early larval stages. Due to its lifestyle, C. inanitus must thus face up to particular physiological constraints imposed by its immature hosts. The venom, along with PDVs produced in the reproductive system of this wasp, are essential for successful parasitism as they protect the parasitoid from encapsulation by host's immune cells [34], interfere with the host's nutritional physiology [35] and induce a developmental arrest in the prepupal stage [18, 36, 37]. Venom of C. inanitus by itself alters the membrane permeability of host hemocytes, has a transient paralytic effect [38] and synergizes the effect of the PDVs on host development [18]. The data gathered on the functions of its venom make C. inanitus a valuable model for investigating the venom proteins. At least 25 proteins were found [38] but their sequences were unknown. The sequences of only two venom proteins from another species of the subfamily Cheloninae, Chelonus sp. near curvimaculatus, had been described to date [39, 40].

We report here the analysis of C. inanitus venom gland products based on the sequencing of clones of a cDNA library and on mass spectrometry analysis of venom proteins. This is the first time that this combination of techniques was applied to identify venom proteins from an endoparasitic wasp. The data obtained might contribute to acquiring a more comprehensive view on the origin and functional diversity of venom proteins among Hymenoptera.

Results and Discussion

General overview of the cDNA library of C. inanitus venom gland

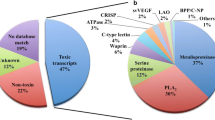

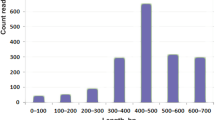

The 2111 ESTs from the venom glands of C. inanitus were clustered into 488 clusters (95 contigs and 393 singletons, Table 1). The number of ESTs in each contig ranged from 2 to 534 and these clusters were considered as putative unigenes. The deduced sequences from 250 clusters (56 contigs and 194 singletons, 56.85% of all ESTs) shared significant similarities with protein sequences deposited in non-redundant databases (EMBL/Genbank), a proportion comparable to that found by Crawford et al. [33] which have studied the venom gland transcriptome of the parasitoid wasp Microctonus hyperodae. Of these products, 164 (corresponding to 36 contigs and 128 singletons, 21.5% of all ESTs) shared significant similarity with proteins with assigned molecular functions in the gene ontology database. This relatively low percentage is explained in part by the fact that the function of the most represented sequence (534 ESTs) referred below as Ci-23a, is unknown. At level 2 of the gene ontology system, clusters were classified into 9 molecular functional categories (Figure 1), among which "binding" (GO:0005488) and "catalytic activity" (GO:0003824) categories were over-represented (95 and 82 clusters respectively). Interestingly, these categories were also the most common functional categories assigned to the venom glands ESTs from the saw-scaled viper, Echis ocellatus[41] and from the solitary hunting wasp species, Orancistrocerus drewseni[42]. Catalytic activity and binding categories thus constitute a hallmark of the venom gland transcriptomes analysed to date. A "structural molecule activity" function (GO:0005198) has been assigned to 48 clusters (20 contigs, 28 singletons) that corresponded essentially to genes coding for structural constituents of ribosomes (17 contigs, 21 singletons). In addition, products of genes functionally annotated as "translation regulator activity" (GO:0045182) (8 singletons) and "transcription regulator activity" (GO:0030528) (2 contigs, 15 singletons) were also identified, which encompassed transcriptional regulators, DNA or RNA binding proteins and translation elongation factors. All these proteins presumably reflect the metabolic effort invested by the venom gland for the transcription and translation of secreted products. The 2111 ESTs were used to produce in silico a database of venom gland open reading frames (vgORFs) which were matched to the peptide sequences obtained by nano-LC-MS/MS analysis. An overall of 1279 ESTs (26 contigs and 7 singletons, 60.6% of all ESTs) were then identified as coding for venom proteins of C. inanitus.

Functional characterization of assembled clusters from C. inanitus venom gland. Histograms show the distribution of sequence clusters from C. inanitus venom gland transcriptome according to the 9 molecular functional categories at level 2 of the gene ontology system. Values figuring at the top of bars indicate the respective number of ESTs classified into each functional category.

Identification of the venom proteins of C. inanitus

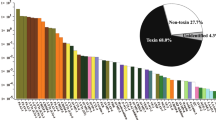

Venoms of parasitic wasps are reputed to have a low content in small proteins and peptides in comparison to venoms of social Hymenoptera [27, 43]. Upon separation of C. inanitus venom proteins by SDS-PAGE, at least 25 proteins with apparent molecular masses ranging from 14 to 300 kDa had been observed while no bands were seen below 14 kDa. This was also consistent with data previously reported [38] from the analysis of SDS-PAGE and two-dimension electrophoresis gels stained with Silver or Coomassie blue staining methods. For the nano-LC-MS/MS analysis presented here, several gradient gels (4-15%) were run at various conditions to allow excision of all gel bands detectable upon Coomassie blue staining. Figure 2 shows that the analysed bands represent the majority of the venom proteins of C. inanitus. However, the presence in this venom of small amounts of additional proteins and peptides cannot be excluded. For 25 proteins, named Ci-14a to Ci-300, peptide sequences exactly matching sequences of the vgORF database were obtained upon nano-LC-MS/MS analysis (see additional file 1: Table of peptide identification). Furthermore, peptides belonging to four additional proteins were detected, namely Vem7, Vem11, Vem17 and Vem37 (Vem being an abbreviation for Venom Mix). These proteins were found in several gel bands, a situation usually found for very abundant proteins. There was no evident correspondence between the relative abundance of venom protein bands on the gel (Figure 2) and the abundance of the corresponding ESTs in the vgORFs database (Table 2). The detailed list of the identified venom proteins will be discussed in the following sections.

SDS-PAGE of venom proteins from C. inanitus. Venom proteins collected from two venom reservoirs were separated on a 4-15% gradient SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. From such gels (run at varying conditions) bands were excised and submitted to nano-LC-MS/MS analysis. Numbers on the right indicate the approximate molecular mass of individual venom proteins for which amino acid sequences were obtained; only for 65, marked with an asterisks, no exploitable sequences were obtained. Molecular mass marker is shown on the left. This figure was modified from [38], with kind permission from Elsevier.

Ci-23a and Ci-45, two proteins with similarities with venom proteins from C. sp. near curvimaculatus

The Ci-23a venom protein was encoded by a contig corresponding to the highest number of ESTs in the library (534). It displays 50% of sequence identity (BlastP, E-value = 7e-21) with a 32.5 kDa protein referred as "venom protein from C. sp. near curvimaculatus" [GenBank:ACI70208.1], another chelonine wasp. This latter protein was historically the first to be isolated and sequenced from the venom of a parasitoid Hymenoptera [39]. Although it was found to be necessary for the survival of the parasitoid in the lepidopteran host, Trichoplusia ni[44], it is still not related to any other known protein and its function remains unknown to date. A potential cleavage site for both N-arginine dibasic convertase (pattern: .RK|RR[^KR]) and subtilisin-like proprotein convertase (pattern: [KR]R.) was detected at positions 51 to 53 (RRA) of the Ci-23a sequence. However, sequences coding for such convertases were not found in our vgORFs database. Remarkably, Ci-23a was devoid of the 12 tandem repeats of 14 residues that characterized the C-terminal part of the venom protein of C. sp. near curvimaculatus (see additional file 2: Amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-23a and the venom protein from C. sp near curvimaculatus) [39]. These repeat sequences form several α-helices with strong amphipathic structures supposed to run at the surface of the protein [39] and we found that they contain an unusualy high number of potential glycosaminoglycan attachment sites (14 serine motifs involved in the motif pattern: [ED]{0,3}.(S) [GA]). Thus Ci-23a, which is much shorter than its homologue, is potentially processed by non-venomous convertases and is likely to have a substrate or target site specificity different from that of the 32.5 kDa venom protein of C. sp. near curvimaculatus. Interestingly, the latter is a very abundant venom protein [44] while Ci-23a protein is of low abundance (Figure 2).

The Ci-45 venom protein, which gives a strong band upon Coomassie staining (Figure 2), shows high similarity (BlastP, 79% identity, E-value = 2e-141) to a 52 kDa chitinase from venom of C. sp. near curvimaculatus [GenBank:AAA61639.1] [40]. Both proteins possess a predicted signal peptide and a glycosyl hydrolase family 18 domain (Pfam: PF00704) with four highly conserved regions present in all known insect chitinases [45–47] (see additional file 3: Amino acid sequence alignment of representative chitinases from different insect species). Members of glycosyl hydrolases 18 family show an eight-stranded α/β barrel catalytic core structure [48]. The 17 residues featuring this functional domain were all found in the Ci-45 sequence, notably those of the second conserved region implicated in catalysis, as shown by previous site-directed mutagenesis studies (consensus sequence: (F/L)DG(L/I)DLD(W/I)EYP)) [47, 49]. Four cysteine residues involved in two disulfide bonds are conserved in the two Cheloninae enzymes and the secondary structures of both proteins were predicted to be highly similar in the placement of α-helix, β-strand and coil structure (data not shown). Ci-45 differs from its homologue by the absence of a C-terminal chitin-binding Peritrophin-A domain (CBM_14, Pfam: PF01607), but this domain does not appear to be essential for the chitinolytic activity of chitinases in Arthropods [46, 50–52]. The Ci-45 contig is thus most likely coding for an active venom chitinase and might be responsible for the chitinase activity previously detected in the venom of C. inanitus[38]. According to the classification proposed by Zhu et al. [47], it belongs to a group of conserved insect chitinases containing a single catalytic domain (group IV). Our phylogenetic analysis (Figure 3) grouped the chitinases from venom glands of C. inanitus and C. sp. near curvimaculatus in a monophyletic clade with that from teratocytes of T. nigriceps [GenBank:AAX69085.1]. Teratocytes are parasitoid wasp secretory cells that circulate into the parasitized host haemolymph, and represent a different way for the wasp to deliver virulence factors into the host. The teratocyte released chitinase from T. nigriceps is hypothesized to contribute to the avoidance of microbial contamination of the host's haemocoel or to facilitate the emergence of parasitoid larvae through the host's cuticle [53]. Other examples of chitinases produced by venom glands were previously reported from spiders [54, Vem7, an ancient yellow-e3-like venom protein Vem7 shares high sequence similarity to the yellow-e3 protein [GenBank:ABB82366.1] from A. mellifera (BlastP, 42% identity, E-value = 2e-81). The yellow-e3 gene is highly expressed in the head and hypopharyngeal gland of honey bee workers and is considered as the progenitor of all genes of major royal jelly proteins (MRJPs) of A. mellifera. Located in the same genomic region and sharing a similar exon/intron organization, MRJPs would have been generated via recent duplications [62, 63]. Recently, two members of the MRJPs family, MRJP8 [GenBank:ACD84799.1] and MRJP9 [GenBank:ACD84800.1], were identified in the venom gland proteome of A. mellifera[5]. It is noteworthy that phylogenetic analyses put them at the basis of the MRJPs tree, meaning that they are the most ancient members of the MRJPs family and suggesting a venomous "pre-royal jelly" function for the MRJPs progenitor originating from yellow-e3 [5, 63]. Our phylogenetic analysis shows that Vem7 forms a monophyletic group with yellow-e-3 protein (Figure 4) and thus represents the first example of a venomous protein in this clade. This supports the hypothesis that a yellow-e-3 gene progenitor of MRJPs may have encoded a venomous protein like the Vem7 gene. Ci-50 is a venom protein belonging to the lipase family (Pfam: PF00151). One carboxyl-esterase and two other lipases were previously identified in the venom proteome of N. vitripennis[28] and a lipase activity has been found in the venom of P. hypochondriaca[64]. In N. vitripennis, venom lipases might participate in the alteration of host's lipid metabolism to the benefit of the develo** parasitoid eggs [65] and a similar function is conceivable for C. inanitus. The partial sequence of the Ci-300 venom protein shares 39% sequence similarity (BlastP, E-value = 2e-05) with a Zinc-dependent metalloprotease identified in the venom of P. hypochondriaca [GenBank:CAD21587.1]. However, Ci-300 lacks the functional characteristic Zn2+-binding motif of HExxHxxGxxH and a distal located methionine [66] found in venom metalloproteinases from the parasitoid species P. hypochondriaca[67], M. aethiopoides[33], Eulophus pennicornis[68] and N. vitripennis[28] (see additional file 6: Partial amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-300 with insect metalloproteases). The sequence of Ci-300 could have thus considerably diverged from an ancestral Zinc-dependent metalloprotease-like protein to acquire an original function in the venom of C. inanitus. The Ci-95 venom protein shows significant sequence similarity to various angiotensin converting enzymes (ACEs, Pfam: PF01401) and notably to an ACE-like protein from A. mellifera [NCBI Reference Sequence:XP_393561.2] (BlastP, 46% identity, E-value = 2e-29). In addition, upon Western analysis with an antibody made against recombinant Drosophila ACE (kindly provided by Dr. Elwyn Isaac, University of Leeds, UK) a clear band was seen (data not shown). ACE is a dipeptidyl carboxydipeptidase with a broad in vitro substrate specificity that is best known, in mammals, for its role in converting inactive angiotensin I to the vasoconstrictor, angiotensin II, and the inactivation of bradykinin [69]. In insects, ACE-like proteins appear to have a wide tissue distribution, from embryos to adult stages [70, 71] and some have been implicated in the metabolic inactivation of neuropeptides in the central nervous system [72]. Dani et al. [73] have detected an ACE-like enzymatic activity in the venom of P. hypochondriaca and have speculated that venomous ACE could be involved in the processing of peptide precursors in the venom reservoir. More recently, another ACE-like enzyme has also been identified in the venom of N. vitripennis[28]. Ci-80a, a venom protein encoded by a single transcript identified in our VgORFs database, belongs to the peptidase family C1, sub-family C1A (papain family, clan CA, Pfam: PF00112). The partial sequence of Ci-80a contains two out of the four conserved residues of the active site of C1A proteases and all the residues involved in the S2 subsite, which is involved in specificity for the dominant substrate of papain-like cysteine proteases. Interestingly, viral cystatins encoded by the genome of the bracovirus CcBV, associated with the parasitic wasp Cotesia congregata, were shown to target some C1A proteases of the host M. sexta[74]. Cathepsins and their inhibitors may play an important role, yet undetermined, in the context of host-parasitoid physiological relationships. The Ci-40a venom protein contains a partial trypsin-like serine protease domain (Pfam: PF00089) but displays low sequence similarities with other known proteases (see additional file 7: Amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-40a with serine protease homologs (SPHs)). At least one of the three residues involved in the catalytic triad for serine protease (aspartate residue in position 111) is present in the partial sequence of Ci-40a. Several serine protease homologs were already reported from parasitoid venoms. In the endoparasitoid C. rubecula, the venom protein Vn50 [GenBank:AAP49428.1] has been found to be a mutated serine protease acting as an inhibitor of the defensive reaction of melanization of host hemolymph [21]. In addition, members of the serine protease protein family were recently identified in the venom proteomes of N. vitripennis[28] and P. puparum[29]. The Ci-120 protein shares significant sequence similarity with insect alpha-N-acetyl glucosaminidases (Pfam: PF05089, EC: 3.2.1.50) and might play a role in proteoglycan metabolism. A C-type lectin domain (Pfam: PF00059) was found in the sequence of the Ci-180 venom protein. The domain extends from positions 76 to 199 of the partial sequence. An immunosuppressive function has been proposed for a lectin with a similar C-type lectin domain, encoded by the genome of the bracovirus CpBV, associated with the parasitic wasp Cotesia plutellae[75]. Since parasitoid venoms and PDVs are used by the wasps to manipulate parasitized host physiology, it might not be surprising that common molecules have been selected for delivery into the host via different pathways. The Ci-14a venom protein belongs to the A10/OS-D insect pheromone-binding protein family (Pfam: PF03392). A high sequence similarity was observed between Ci-14a and Csp3 from A. mellifera (BlastP, 56% identity, E-value = 5e-27), another member of the A10/OS-D protein family. Csp3 [GenBank:ABH88171.1] is a chemosensory protein (CSP) ubiquitously expressed in adults and pre-imaginal stages of the honeybee in which it may play a role in cuticle maturation [76]. Ci-23b is a venom protein containing a pheromone binding protein/general-odorant binding protein (PBP/GOBP) domain (Pfam: PF01395). Homology searches revealed that Ci-23b has highly diverged from known PBPs and GOBPs. In particular, it only shows 4 out of the 6 cystein residues strictly conserved between PBPs and GOBPs [77, 78]. Other OBP-like venom proteins, unrelated to Ci-23b, have previously been identified in the venom proteomes of A. mellifera workers and N. vitripennis females (NCBI Reference Sequences: NP_001035313.1 and NP_001155150.1, respectively) [5, 28]. Beside the involvement of PBPs and OBPs in chemical communication, it is possible that in Hymenoptera, some OBP-like proteins fulfil other roles in relation with the venomous functions. Ci-48a, Vem17 and Ci-80b venom proteins share sequence similarities with members of a group of proteins similar to protein isoforms A [GenBank:AAF46301.1] and B [GenBank:AAS65275.1] encoded by the lethal (1) G0193 gene from D. melanogaster. This group of cystein-rich proteins notably includes several venom and salivary gland proteins of unknown functions reported from various insect species (see additional file 8: Sequence similarities between Ci-48a, Vem17 and Ci-80b and proteins similar to isoforms of lethal (1) G0193). Ci-80b possesses the least conserved amino acid sequence towards lethal (1) G0193 isoforms suggesting it might have diverged as a virulence factor involved in host-parasite interactions, which are often characterized by a high level of divergence. In addition to Ci-23a and Ci-45 which are conserved in the venom of two Chelonus species, ten C. inanitus venom proteins did not show any significant sequence similarity to known proteins (Ci-14b, Ci-15, Ci-27, Ci-28, Ci-35a, Ci-35b, Ci-40c, Ci-60, Vem11 and Vem 37). This is reminiscent of observations on twenty three venom proteins in N. vitripennis which also have no similarity to known proteins and appear to be lineage- and/or species specific [28]. Given that Chelonines are egg-larval parasitoids it is possible that new C. inanitus proteins have evolved to cope with this particular parasitic context. Although they do not contain conserved domains, they may play an important role during host-parasite interaction and notably Ci-14b, the second most abundant sequence of the transcriptome (286 ESTs). In addition to proteins identified by mass spectrometry, several ESTs encoding putative venom proteins were identified in our vgORFs database (Table 3). Five ESTs encoded partial sequences of at least three different hyaluronidase-like proteins that show significant sequence similarities to venom hyaluronidases described from several hymenopteran species [79]. One EST encoded a venom allergen 5-like protein (Figure 5). Venom allergen 5 proteins (also called antigens 5) are commonly found in venoms of social Hymenoptera of the superfamilly Vespoidea [80]. They belong to a wider group of proteins expressed by salivary and venom glands of distant animal species, recently gathered under the proposed term of CAP proteins for "Cystein-rich secretory proteins, Antigen 5 and Pathogenesis-related proteins" [56]. CAP domain proteins are the dominant allergy-inducing toxins in hymenopteran venoms [81], and a related CAP protein has previously been identified from the venom of M. hyperodae[33].Putative enzymes

Lectin-like venom protein

CSP-like and OBP-like proteins

Venom proteins similar to lethal (1) G0193 isoforms

New lineage-specific proteins

Additional putative venom proteins identified from the vgORFs database

Conclusions

In this paper we report the identification of the majority of venom proteins of the egg-larval endoparasitoid wasp C. inanitus. We combined technical approaches which we had successfully used to elucidate the origin of bracoviruses [82]. They are powerful tools to study evolutionary and functional aspects of parasitoid-associated factors. The most highly redundant set of sequences encoded a protein (Ci-23a) that shared sequence similarity with a venom protein previously identified in the related species C. sp. near curvimaculatus[39]. These venom proteins are thus likely to play a key role, as yet undetermined, in the life cycle of Cheloninae egg-larval endoparasitoids. In addition, we have identified 453 unigenes that, for the most part, are likely to code for nonsecretory products of the venom glands.

A striking feature of C. inanitus venom was the redundancy of components able to interact with chitin. These components might be important when intermediate or late stages of eggs are parasitized. In this case, the parasitoid larva has to bore itself into the host embryo which is surrounded by an embryonic cuticle [83] and chitinases might help to facilitate this process.

A number of C. inanitus venom proteins and enzymes shared similarities to venom gland products from other species that also belong to the Ichneumonoidea superfamily (M. hyperodae, M. aethiopoides, P. hypochondriaca). Sequence similarities were also found with venom proteins from more distant apocritan species representative from Chalcidoidea (N. vitripennis), Vespoidea (O. drewseni, Anoplius samariensis, Dolichovespula arenaria) and Apoidea (A. mellifera, Apis cerana cerana) superfamilies (see additional file 9: Phylogeny of the major superfamilies of Hymenoptera). The presence of related venom proteins in species that do not share the same ecological constraints and lifestyles can partly be explained by independent recruitment of these proteins during species evolution [56]. Our phylogenetic analyses suggest this is the case for the venom chitinases of the Cheloninae species and the venom chitinase 5 of N. vitripennis that were acquired independently. However, given that all modern Apocrita share a common ancestral parasitic origin [84], it is also expected that some lineages have conserved ancestral venom genes. Our finding of mRNA coding for a member of the allergen 5 proteins family in the venom glands of C. inanitus appears to be an example of such conservation. The sequence of the deduced protein is placed, with the allergen 5 from the venom of M. hyperodae and N. vitripennis in a monophyletic clade with respect to the phylogenetic tree of allergen 5 proteins found in vespid and ant venoms (Figure 5). This result suggests that the ancestral gene was expressed by the venom glands of the common ancestor of Ichneumonoidea and Aculeata, 155 to 185 million years ago [84] and could have been lost in Apoidea. Allergen 5 proteins would thus be representative of one of the most ancient group of insect venom proteins.

Another interesting point is the discovery of a yellow-e3-like protein, Vem7, in the venom of C. inanitus which give more indications on the evolutionary history of the yellow-e3 gene family among Hymenoptera. Interestingly the recent genome sequencing of N. vitripennis has revealed the largest number of yellow/MRJP genes so far found in any insect, including an independent amplification of MRJP-like proteins [85]. It would be worthy to determine if some of these genes have a venomous function in Nasonia species.

On a more general standpoint, once increasing number of comprehensive analyses will become available, our work on the venom composition of C. inanitus will contribute to retracing the evolution of venomous functions within Hymenoptera by comparison of the venomous arsenal of different species.

Methods

Insects

C. inanitus (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), a solitary egg-larval parasitoid, was reared on one of its natural hosts S. littoralis. Adult S. littoralis were kindly provided by Syngenta AG, Stein, Switzerland. They were raised at 27°C at a LD photoperiod of 14 h:10 h and fed with an artificial diet. Diet was prepared from dry powder (Beet Army Worm Diet, Bio Serv, Frenchtown, New Jersey, USA).

Collection of venom glands and RNA isolation

Female wasps were anaesthetized on ice for several minutes and then shortly rinsed in 70% ethanol. The abdominal organs were gently pulled out with forceps and the reproductive apparatus was placed in 50 μl sterile Insect Ringer. Then, the venom gland filaments were dissected, washed in sterile Ringer, put into an Eppendorf tube containing 200 μl of RNAlater™(Qiagen) and stored at - 80°C until RNA isolation. The morphology of the C. inanitus venom gland was previously described by Kaeslin et al. [38]. For RNA isolation, venom gland filaments from 60 female wasps were used; no homogenization was necessary and 0.45 ml Lysis buffer RLT (Qiagen) including 143 mM β-mercaptoethanol was added followed by a proteinase K digestion as described by Johner and Lanzrein [86]. The RNA isolation (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen) including an on column DNase digestion (RNase-free DNase I) was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Total RNA was eluted from the column with 100 μl RNase-free water. A second digestion with DNase I was carried out and the RNA was then extracted with acidic phenol; the RNA was precipitated as described in [87]. The yield was 9 μg of total RNA.

cDNA library construction

A cDNA library was constructed with the Creator SMART cDNA Library Construction Kit (BD Biosciences, Ozyme, France) following the supplier's instructions. The first strand cDNA was synthesized from 481 ng of total RNA extracted from C. inanitus venom glands. The cDNA were ligated into pDNR-LIB (BD Biosciences Clontech) and ligation products were transformed into ElectroMax DH10B-T1 Phage Resistant Escherichia coli Competent Cells (Invitrogen, Fisher Scientific, France).

Sequencing and ESTs quality control

To obtain an unbiased overview of the venom gland transcriptome, colonies were amplified with the ϕ29 DNA polymerase by rolling circle amplification. Sequencing was done on a ABI sequencer using the standard M13 forward primer and BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Initially 384 clones from the library were analyzed for the presence of venom proteins-related sequences. These were detected and a sequencing of a total of 2500 clones was performed. The EST sequences obtained were analysed for quality control; base calling step was performed with the Phred program f(S9). Low quality bases (phred score < 20) were masked and sequences with more than 30% n-content, or shorter than 60 bp (after vector/adaptator sequences removing) were removed.

ESTs clustering and assembly

After discarding the poor-quality sequences, 2111 high-quality ESTs were subjected to clustering using the TIGR software TGI Clustering tool (TGICL) [88]. The clustering was performed by a modified version of NCBI's megablast. EST sequences were assigned to clusters based on identity: the clustering parameters were 98% minimum percent identity for overlaps, for a minimum overlap length of 40 nt and a maximum length of unmatched overhangs of 20 nt.

Sequences from each cluster were assembled into consensus sequences called "contigs" using the CAP3 assembly program [89] available in TGICL. Sequences from a cluster containing only one sequence were called "singletons".

ESTs annotation

To identify similarities with known proteins, the sequences of contigs and singletons were searched using the BLASTX algorithm against a local non-redundant protein database (NR, NCBI) with a cut-off E-value of 1e-5. To define the function of the contigs and singletons, we used the Gene Ontology (GO) controlled vocabulary [90] and more particularly GOSlim, a subset of GO terms, which provides a higher level of annotations and allows a more global view of the dataset. To this end, an automated GO-annotation of the sequences of contigs and singletons that showed a significant similarity with a Uniprot entry was achieved using the Blast2go software [91], with a stringency cut-off of 1e-6.

Collection of venom, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and protein identification

Wasps were anaesthetized on ice and their venom apparatus (venom gland filaments and reservoir) was dissected. For each protein separation the venom of four wasps was collected. The venom was collected by piercing the reservoirs with a glass capillary. The sucked up venom was collected in 10 μl sterile H2O and mixed with 10 μl sample buffer (0.125 M Tris-HCl pH 6.5, 4% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol) and heated at 90°C for 6 minutes. For separation of proteins, precast linear gradient READY GEL (BIO RAD) 4-15%Tris-HCl gels with 10 wells were used. Two equivalents of venom (i.e. the amount of venom collected from two reservoirs) were loaded per lane. Electrophoresis was in 0.02 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 0.19 M glycine, and 0.1% (w/v) SDS. A constant voltage of 150 V was applied. As marker the High-Range Rainbow™Molecular Weight Marker (GE Healthcare) was used. Staining was done with SERVA blue R (Coomassie) Brilliant Blue R-250 according to the manufacturer's protocol. For protein identification, gel slices were cut out, transferred into Eppendorf tubes and covered with 20 μl ethanol (20%). Treatment of gel slices and nano-LC-MS/MS analysis was as described in [82]. CID spectra were extracted into data files by Bioworks (Rev.3.3.1, Thermo Scientific) without any filters applied. Combined dta files were automatically matched to our personal database of vgORFs by Phenyx software, Version 2.5 (Genebio SA, Geneva, Switzerland). N-terminal sequencing was done by Edman degradation.

Sequence analysis

Each cluster of nucleotide sequences was annotated by being searched against GenBank NCBI database [92] with BLAST algorithms. Since amino acid sequences are more useful to detect homology over long periods, the assembled sequences were translated on-line into the correct open reading frames (ORFs) using ORFINDER tool from NCBI [93] and compared to the sequences in the NCBI nr and Swissprot protein databases. Sequences that did not match were further compared against the Genbank nucleotide databases (Blastn).

The signalP algorithm [94] was accessed online to predict the presence of signal peptides. The deduced amino acid sequences of all the proteins identified by nano-LC-MS/MS analysis were annotated by searching against Pfam protein families database [95]. Modification, cleavage and functional sites were predicted by the ELM server [96].

For amino acid sequence alignments, sequences were retrieved from NCBI nr database, aligned with sequences from C. inanitus with the program MAFFT version 6.0 [97] and edited with the program Jalview [98]. Alignment refinement was done with Gblocks software (version 0.91b) [99]. Phylogenetic relationships were estimated by Bayesian MCMC analyses using the program MrBayes 3.1.2 [100] available online [101, 102]. For each set of aligned sequences, we implemented a mixed model of amino acid substitution, with gamma-correction for heterogeneity rate among residues and correction for invariable residues. Model of protein evolution was selected using ProtTest 2.4 software [103].

References

Kuhn-Nentwig L: Antimicrobial and cytolytic peptides of venomous arthropods. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003, 60: 2651-2668. 10.1007/s00018-003-3106-8.

Hoffman DR: Hymenoptera venom allergens. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2006, 30: 109-128. 10.1385/CRIAI:30:2:109.

Wiese MD, Chataway TK, Davies NW, Milne RW, Brown SGA, Gai W-P, Heddle RJ: Proteomic analysis of Myrmecia pilosula (jack jumper) ant venom. Toxicon. 2006, 47: 208-217. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2005.10.018.

Kolarich D, Loos A, Léonard R, Mach L, Marzban G, Hemmer W, Altmann F: A proteomic study of the major allergens from yellow jacket venoms. Proteomics. 2007, 7: 1615-1623. 10.1002/pmic.200600800.

Peiren N, Vanrobaeys F, de Graaf DC, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, Jacobs FJ: The protein composition of honeybee venom reconsidered by a proteomic approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1752: 1-5.

Padavattan S, Schmidt M, Hoffman DR, Marković-Housley Z: Crystal structure of the major allergen from fire ant venom, Sol i 3. J Mol Biol. 2008, 383: 178-185. 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.023.

de Graaf DC, Aerts M, Danneels E, Devreese B: Bee, wasp and ant venomics pave the way for a component-resolved diagnosis of sting allergy. J Proteomics. 2009, 72: 145-154. 10.1016/j.jprot.2009.01.017.

Pennacchio F, Strand MR: Evolution of developmental strategies in parasitic Hymenoptera. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006, 51: 233-258. 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151029.

Whitfield JB: Phylogenetic insights into the evolution of parasitism in Hymenoptera. Adv Parasitol. 2003, 54: 69-100. full_text.

Doury G, Bigot Y, Periquet G: Physiological and biochemical analysis of factors in the female venom gland and larval salivary secretions of the ectoparasitoid wasp Eupelmus orientalis. J Insect Physiol. 1997, 43: 69-81. 10.1016/S0022-1910(96)00053-4.

Nakamatsu Y, Tanaka T: Venom of ectoparasitoid, Euplectrus sp near plathypenae (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) regulates the physiological state of Pseudaletia separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) host as a food resource. J Insect Physiol. 2003, 49: 149-159. 10.1016/S0022-1910(02)00261-5.

Abt M, Rivers DB: Characterization of phenoloxidase activity in venom from the ectoparasitoid Nasonia vitripennis (Walker) (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). J Invertebr Pathol. 2007, 94: 108-118. 10.1016/j.jip.2006.09.004.

Beckage NE, Gelman DB: Wasp parasitoid disruption of host development: implications for new biologically based strategies for insect control. Annu Rev Entomol. 2004, 49: 299-330. 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123324.

Asgari S: Venom proteins from polydnavirus-producing endoparasitoids: their role in host-parasite interactions. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2006, 61: 146-156. 10.1002/arch.20109.

Asgari S: Endoparasitoid venom proteins as modulators of host immunity and development. Recent Advances in the Biochemistry, Toxicity, and Mode of Action of Parasitic Wasp Venoms. Edited by: Rivers D, Yoder J. 2007, Kerala: Research Signpost, 57-73.

Poirié M, Carton Y, Dubuffet A: Virulence strategies in parasitoid Hymenoptera as an example of adaptive diversity. C R Biol. 2009, 332: 311-320.

Moreau SJM, Huguet E, Drezen JM: Polydnaviruses as tools to deliver wasp virulence factors to impair lepidopteran host immunity. Insect Infection and Immunity: Evolution, Ecology and Mechanisms. Edited by: Rolff J, Reynolds SE. 2009, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 137-158. full_text.

Soller M, Lanzrein B: Polydnavirus and venom of the egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus inanitus (Braconidae) induce developmental arrest in the prepupa of its host Spodoptera littoralis (Noctuidae). J Insect Physiol. 1996, 42: 471-481. 10.1016/0022-1910(95)00132-8.

Zhang G, Schmidt O, Asgari S: A novel venom peptide from an endoparasitoid wasp is required for expression of polydnavirus genes in host hemocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279: 41580-41585. 10.1074/jbc.M406865200.

Asgari S, Zareie R, Zhang G, Schmidt O: Isolation and characterization of a novel venom protein from an endoparasitoid, Cotesia rubecula (Hym: Braconidae). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2003, 53: 92-100. 10.1002/arch.10088.

Asgari S, Zhang G, Zareie R, Schmidt O: A serine proteinase homolog venom protein from an endoparasitoid wasp inhibits melanization of the host hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003, 33: 1017-1024. 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00116-4.

Colinet D, Dubuffet A, Cazes D, Moreau S, Drezen JM, Poirié M: A serpin from the parasitoid wasp Leptopilina boulardi targets the Drosophila phenoloxidase cascade. Dev Comp Immunol. 2009, 33: 681-689. 10.1016/j.dci.2008.11.013.

Labrosse C, Stasiak K, Lesobre J, Grangeia A, Huguet E, Drezen J-M, Poirie M: A RhoGAP protein as a main immune suppressive factor in the Leptopilina boulardi (Hymenoptera, Figitidae)-Drosophila melanogaster interaction. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2005, 35: 93-103. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.10.004.

Zhang GM, Schmidt O, Asgari S: A calreticulin-like protein from endoparasitoid venom fluid is involved in host hemocyte inactivation. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006, 30: 756-764. 10.1016/j.dci.2005.11.001.

Richards EH, Dani MP: Biochemical isolation of an insect haemocyte anti-aggregation protein from the venom of the endoparasitic wasp, Pimpla hypochondriaca, and identification of its gene. J Insect Physiol. 2008, 54: 1041-1049. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2008.04.003.

Colinet D, Schmitz A, Depoix D, Crochard D, Poirié M: Convergent use of RhoGAP toxins by eukaryotic parasites and bacterial pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3: e203-10.1371/journal.ppat.0030203.

Moreau SJM, Guillot S: Advances and prospects on biosynthesis, structures and functions of venom proteins from parasitic wasps. Insect Biochem Molec Biol. 2005, 35: 1209-1223. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2005.07.003.

de Graaf DC, Aerts M, Brunain M, Desjardins CA, Jacobs FJ, Werren JH, Devreese B: Insights into the venom composition of the ectoparasitoid wasp Nasonia vitripennis from bioinformatic and proteomic studies. Insect Mol Biol. 2010, 19 (Suppl. 1): 11-26. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00914.x.

Zhu J-Y, Fang Q, Wang L, Hu C, Ye G-Y: Proteomic analysis of the venom from the endoparasitoid Pteromalus puparum (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2010, 75: 28-44. 10.1002/arch.20380.

Parkinson N, Smith I, Weaver R, Edwards JP: A new form of arthropod phenoloxidase is abundant in venom of the parasitoid wasp Pimpla hypochondriaca. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001, 31: 57-63. 10.1016/S0965-1748(00)00105-3.

Parkinson NM, Conyers C, Keen JN, MacNicoll AD, Weaver ISR: cDNAs encoding large venom proteins from the parasitoid wasp Pimpla hypochondriaca identified by random sequence analysis. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 2003, 134: 513-520.

Parkinson NM, Conyers C, Keen J, MacNicoll A, Smith I, Audsley N, Weaver RJ: Towards a comprehensive view of the primary structure of venom proteins from the parasitoid wasp Pimpla hypochondriaca. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004, 34: 565-571. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.003.

Crawford AM, Brauning R, Smolenski G, Ferguson C, Barton D, Wheeler TT, McCulloch A: The constituents of Microctonus sp. parasitoid venoms. Insect Mol Biol. 2008, 17: 313-324. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00802.x.

Stettler P, Trenczek T, Wyler T, Pfister-Wilhelm R, Lanzrein B: Overview of parasitism associated effects on host haemocytes in larval parasitoids and comparison with effects of the egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus inanitus on its host Spodoptera littoralis. J Insect Physiol. 1998, 44: 817-831. 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00014-6.

Kaeslin M, Pfister-Wilhelm R, Lanzrein B: Influence of the parasitoid Chelonus inanitus and its polydnavirus on host nutritional physiology and implications for parasitoid development. J Insect Physiol. 2005, 51: 1330-1339. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2005.08.003.

Grossniklaus-Bürgin C, Pfister-Wilhelm R, Meyer V, Treiblmayr K, Lanzrein B: Physiological and endocrine changes associated with polydnavirus/venom in the parasitoid host system Chelonus inanitus-Spodoptera littoralis. J Insect Physiol. 1998, 44: 305-321.

Pfister-Wilhelm R, Lanzrein B: Stage dependent influences of polydnaviruses and the parasitoid larva on host ecdysteroids. J Insect Physiol. 2009, 55: 707-715. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2009.04.018.

Kaeslin M, Reinhard M, Bühler D, Roth T, Pfister-Wilhelm R, Lanzrein B: Venom of the egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus inanitus is a complex mixture and has multiple biological effects. J Insect Physiol. 2010, 56: 686-694. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2009.12.005.

Jones D, Sawickill G, Wozniak M: Sequence, structure, and expression of a wasp venom protein with a negatively charged signal peptide and a novel repeating internal structure. J Biol Chem. 1992, 267: 14871-14878.

Krishnan A, Nair PN, Jones D: Isolation, cloning, and characterization of new chitinase stored in active form in chitin-lined venom reservoir. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269: 20971-20976.

Wagstaff SC, Harrison RA: Venom gland EST analysis of the saw-scaled viper, Echis ocellatus, reveals novel 91 integrin-binding motifs in venom metalloproteinases and a new group of putative toxins, renin-like aspartic proteases. Gene. 2006, 377: 21-32. 10.1016/j.gene.2006.03.008.

Baek JH, Woo TH, Kim CB, Park JH, Kim H, Lee S, Lee SH: Differential gene expression profiles in the venom gland/sac of Orancistrocerus drewseni (Hymenoptera: Eumidae). Archives Insect Biochem Physiol. 2009, 71: 205-222. 10.1002/arch.20316.

Leluk J, Schmidt J, Jones D: Comparative studies on the protein composition of Hymenopteran venom reservoirs. Toxicon. 1989, 27: 105-114. 10.1016/0041-0101(89)90410-8.

Taylor T, Jones D: Isolation and characterization of the 32.5 kDa protein from the venom of an endoparasitic wasp. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990, 1035: 37-43.

Kramer KJ, Muthukrishnan S: Insect chitinases: molecular biology and potential use as biopesticides. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997, 27: 887-900. 10.1016/S0965-1748(97)00078-7.

de la Vega H, Specht CA, Liu Y, Robbins PW: Chitinases are a multi-gene family in Aedes, Anopheles and Drosophila. Insect Mol Biol. 1998, 7: 233-239. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1998.00065.x.

Zhu Q, Arakane Y, Banerjee D, Beeman RW, Kramer KJ, Muthukrishnan S: Domain organization and phylogenetic analysis of the chitinase-like family of proteins in three species of insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2008, 38: 452-466. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.06.010.

Henrissat B: Classification of chitinases modules. EXS. 1999, 87: 137-156.

Zhang H, Huang X, Fukamizo T, Muthukrishnan S, Kramer KJ: Site-directed mutagenesis and functional analysis of an active site tryptophan of insect chitinase. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002, 32: 1477-1488. 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00068-1.

Wang X, Ding X, Gopalakrishnan B, Morgan TD, Johnson L, White FF, Muthukrishnan S, Kramer KJ: Characterization of a 46 kDa insect chitinase from transgenic tobacco. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996, 26: 1055-1064. 10.1016/S0965-1748(96)00056-2.

Girard C, Jouanin L: Molecular cloning of a gut-specific chitinase cDNA from the beetle Phaedon cochleariae. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1999, 29: 549-556. 10.1016/S0965-1748(99)00029-6.

Han JH, Lee KS, Li J, Kim I, Je YH, Kim DH, Sohn HD, ** BR: Cloning and expression of a fat body-specific chitinase cDNA from the spider, Araneus ventricosus. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2005, 140: 427-435. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.11.009.

Cônsoli FL, Lewis D, Keeley L, Vinson SB: Characterization of a cDNA encoding a putative chitinase from teratocytes of the endoparasitoid Toxoneuron nigriceps. Entomol Exp Appl. 2007, 122: 271-278.

de F Fernandes-Pedrosa, de LM Junqueira-de-Azevedo, Gonçalves-de-Andrade RM, Kobashi LS, Almeida DD, Ho PL, Tambourgi DV: Transcriptome analysis of Loxosceles laeta (Araneae, Sicariidae) spider venomous gland using expressed sequence tags. BMC Genomics. 2008, 9: 279-10.1186/1471-2164-9-279.

Chen J, Zhao L, Jiang L, Meng E, Zhang Y, **ong X, Liang S: Transcriptome analysis revealed novel possible venom components and cellular processes of the tarantula Chilobrachys **gzhao venom gland. Toxicon. 2008, 52: 794-806. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.08.003.

Fry BG, Roelants K, Champagne DE, Scheib H, Tyndall JDA, King GF, Nevalainen TJ, Norman JA, Lewis RJ, Norton RS, Renjifo C, Rodriguez de la Vega RC: The toxicogenomic multiverse: Convergent recruitment of proteins into animal venoms. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009, 10: 483-511. 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164356.

Watanabe T, Uchida M, Kobori K, Tanaka H: Site-directed mutagenesis of the Asp-197 and Asp-202 residues in chitinase A1 of Bacillus circulans WL-12. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994, 58: 2283-2285. 10.1271/bbb.58.2283.

Lu Y, Zen KC, Muthukrishnan S, Kramer KJ: Site-directed mutagenesis and functional analysis of active site acidic amino acid residues D142, D144 and E146 in Manduca sexta (tobacco hornworm) chitinase. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2002, 32: 1369-1382. 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00057-7.

Varela PF, Llera AS, Mariuzza RA, Tormo J: Crystal structure of imaginal disc growth factor-2. A member of a new family of growth-promoting glycoproteins from Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277: 13229-13236. 10.1074/jbc.M110502200.

Kanost MR, Zepp MK, Ladendorff NE, Andersson LA: Isolation and characterization of a hemocyte aggregation inhibitor from hemolymph of Manduca sexta larvae. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1994, 27: 123-136. 10.1002/arch.940270205.

Calvo E, Pham VM, Marinotti O, Andersen JF, Ribeiro JM: The salivary gland transcriptome of the neotropical malaria vector Anopheles darlingi reveals accelerated evolution of genes relevant to hematophagy. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 57-10.1186/1471-2164-10-57.

Albert S, Klaudiny J: The MRJP/YELLOW protein family of Apis mellifera: Identification of new members in the EST library. J Insect Physiol. 2004, 50: 51-59. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2003.09.008.

Drapeau MD, Albert S, Kucharski R, Prusko C, Maleszka R: Evolution of the Yellow/Major Royal Jelly Protein family and the emergence of social behavior in honey bees. Genome Res. 2006, 16: 1385-1394. 10.1101/gr.5012006.

Dani MP, Edwards JP, Richards EH: Hydrolase activity in the venom of the pupal endoparasitic wasp, Pimpla hypochondriaca. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2005, 141: 373-381. 10.1016/j.cbpc.2005.04.010.

Rivers DB, Denlinger DL: Venom-induced alterations in fly lipid-metabolism and its impact on larval development of the ectoparasitoid Nasonia vitripennis (Walker) (Hymenoptera, Pteromalidae). J Invertebr Pathol. 1995, 66: 104-110. 10.1006/jipa.1995.1071.

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ: Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995, 248: 183-228. full_text.

Parkinson N, Conyers C, Smith I: A venom protein from the endoparasitoid wasp Pimpla hypochondriaca is similar to snake venom reprolysin-type metalloproteases. J Invertebr Pathol. 2002, 79: 129-131. 10.1016/S0022-2011(02)00033-2.

Price DR, Bell HA, Hinchliffe G, Fitches E, Weaver R, Gatehouse JA: A venom metalloproteinase from the parasitic wasp Eulophus pennicornis is toxic towards its host, tomato moth (Lacanobia oleracae). Insect Mol Biol. 2009, 18: 195-202. 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00864.x.

Ondetti MA, Cushman DW: Enzymes of the rennin-angiotensin system and their inhibitors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1982, 51: 283-308. 10.1146/annurev.bi.51.070182.001435.

Isaac RE, Schoofs L, Williams TA, Corvol P, Veelaert D, Sajid M, Coates D: Toward a role for angiotensin-converting enzyme in insects. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998, 839: 288-292. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10777.x.

Macours N, Hens K: Zinc-metalloproteases in insects: ACE and ECE. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2004, 34: 501-510. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.03.007.

Isaac RE, Bland ND, Shirras AD: Neuropeptidases and the metabolic inactivation of insect neuropeptides. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009, 162: 8-17. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2008.12.011.

Dani MP, Richards EH, Isaac RE, Edwards JP: Antibacterial and proteolytic activity in venom from the endoparasitic wasp Pimpla hypochondriaca (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae). J Insect Physiol. 2003, 49: 945-954. 10.1016/S0022-1910(03)00163-X.

Serbielle C, Moreau S, Veillard F, Voldoire E, Mannucci M-A, Volkoff A-N, Drezen J-M, Lalmanach G, Huguet E: Identification of parasite-responsive cysteine proteases in Manduca sexta. Biol Chem. 2009, 390: 493-502. 10.1515/BC.2009.061.

Lee S, Nalini M, Kim Y: A viral lectin encoded in Cotesia plutellae bracovirus and its immunosuppressive effect on host hemocytes. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A Mol Integr Physiol. 2008, 149: 351-361. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.007.

Forêt S, Wanner KW, Maleszka R: Chemosensory proteins in the honey bee: Insights from the annotated genome, comparative analyses and expressional profiling. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007, 37: 19-28.

Tegoni M, Campanacci V, Cambillau C: Structural aspects of sexual attraction and chemical communication in insects. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004, 29: 257-264. 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.003.

Xu YL, He P, Zhang L, Fang SQ, Dong SL, Zhang YJ, Li F: Large-scale identification of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins from expressed sequence tags in insects. BMC Genomics. 2009, 10: 632-10.1186/1471-2164-10-632.

Gmachl M, Kreil G: Bee venom hyaluronidase is homologous to a membrane protein of mammalian sperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993, 90: 3569-3573. 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3569.

Lu G, Villalba M, Coscia MR, Hoffman DR, King TP: Sequence analysis and antigenic cross-reactivity of a venom allergen, antigen 5, from hornets, wasps, and yellow jackets. J Immunol. 1993, 150: 2823-2830.

Fang KSY, Vitale M, Fehlner P, King TP: cDNA cloning and primary structure of a white-face hornet venom allergen, antigen 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988, 85: 895-899. 10.1073/pnas.85.3.895.

Bézier A, Annaheim M, Herbinière J, Wetterwald C, Gyapay G, Bernard-Samain S, Wincker P, Roditi I, Heller M, Belghazi M, Pfister-Wilhem R, Periquet G, Dupuy C, Huguet E, Volkoff AN, Lanzrein B, Drezen JM: Polydnaviruses of braconid wasps derive from an ancestral nudivirus. Science. 2009, 323: 926-930.

Kaeslin M, Wehrle I, Grossnikluas-Bürgin C, Wyler T, Guggisberg U, Schittny JC, Lanzrein B: Stage-dependent strategies of host invasion in the egg-larval parasitoid Chelonus inanitus. J Insect Physiol. 2005, 51: 287-296. 10.1016/j.**sphys.2004.11.015.

Grimaldi D, Engel MS: Evolution of the insects. 2005, New York: Cambridge University Press

The Nasonia Genome Working Group, et al: Functional and evolutionary insights from the genomes of three parasitoid Nasonia species. Science. 2010, 327: 343-348. 10.1126/science.1178028.

Johner A, Lanzrein B: Characterization of two genes of the polydnavirus of Chelonus inanitus and their stage-specific expression in the host Spodoptera littoralis. J Gen Virol. 2002, 83: 1075-1085.

Johner A, Stettler P, Gruber A, Lanzrein B: Presence of polydnavirus transcripts in an egg-larval parasitoid and its lepidopterous host. J Gen Virol. 1999, 80: 1847-1854.

Pertea G, Huang X, Liang F, Antonescu V, Sultana R, Karamycheva S, Lee Y, White J, Cheung F, Parvizi B, Tsai J, Quackenbush J: TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 651-652. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034.

Huang X, Madan A: CAP3: A DNA sequence assembly program. Genome Res. 1999, 9: 868-877. 10.1101/gr.9.9.868.

Gene Ontology Consortium: The Gene Ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, D322-D326. 10.1093/nar/gkj021. 34 Database

Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M: Blast2GO: A universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 3674-3676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610.

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast]

ORF Finder. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gorf/]

SignalP 3.0 Server. [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP]

Pfam 24.0 home page. [http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/]

ELM server. [http://elm.eu.org/]

Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T: MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acid Res. 2002, 30: 3059-3066. 10.1093/nar/gkf436.

Clamp M, Cuff J, Searle SM, Barton GJ: The Jalview Java alignment editor. Bioinformatics. 2004, 20: 426-427. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg430.

Castresana J: Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000, 17: 540-552.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP: MrBayes3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 1572-1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180.

Phylogeny.fr: Home. [http://www.phylogeny.fr]

Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, Chevenet F, Dufayard JF, Guindon S, Lefort V, Lescot M, Claverie JM, Gascuel O: Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36: 465-469. 10.1093/nar/gkn180.

Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D: ProtTest: Selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 2104-2105. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the French Agency for National Research (ANR 09-BLAN-0243-01) and the French GDR 2153, as well as the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 3100A0-116067 to BL). Many thanks to Dr E. Huguet for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

BV and SM carried out the cDNA library construction, sequence alignments and annotations, performed the phylogenetic analyses and drafted the manuscript. TR isolated the venom gland RNA and participated in the preparation of venom proteins for sequencing. MK participated in the preparation of venom proteins and their sequence analysis. MH carried out the LC-MS/MS analyses and CID spectral interpretation. JS carried out the N-terminal sequencing. JP coordinated ESTs sequencing and quality controls. FC performed ESTs clustering and assembling. BL coordinated the proteomic study and the extraction of RNA from C. inanitus venom gland. JMD and MP participated in the design and coordination of the transcriptomic study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2010_10143_MOESM1_ESM.XLS

Additional file 1:Table of peptide identification. Peptidic sequences obtained from the nano-LC-MS/MS analysis of venom proteins from C. inanitus are shown in blue into the corresponding amino acid sequences encoded by ORFs obtained from the transcriptome analysis of C. inanitus venom glands. (XLS 16 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM2_ESM.PNG

Additional file 2:Amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-23a and the venom protein from C. sp near curvimaculatus. The amino acid sequence of the venom protein from C. sp near curvimaculatus was retrieved from GenBank [GenBank:ACI70208.1]. The position of a potential cleavage site for both N-arginine dibasic convertase and subtilisin-like proprotein convertase is boxed in black in the Ci-23a sequence. Red and green arrows indicate the beginning of the predicted signal peptide and mature protein sequences of Ci-23a, respectively. Serine residues that potentially serve as glycosaminoglycan attachment sites are indicated by blue triangles under the sequence of the venom protein from C. sp near curvimaculatus. Sequence printed in bold was also obtained by N-terminal sequencing of the Ci-23a protein. (PNG 47 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM3_ESM.PNG

Additional file 3:Amino acid sequence alignment of representative chitinases from different insect species. The sequence of the Ci-45 venom chitinase from C. inanitus was aligned with sequences of chitinases from the following species: the parasitic wasps C. sp. near curvimaculatus [GenBank:AAA61639.1], T. nigriceps [GenBank:AAX69085.1] and N. vitripennis [GenBank:NP_001128139.2] and the beetle Monochamus alternatus [GenBank:BAF49605.1]. The four conserved regions are boxed. Black triangles indicate catalytic residues. Locations of the glycosyl hydrolase family 18 and chitin-binding Peritrophin-A (CBM_14) domains are indicated by blue and green lines, respectively. Red and green arrows indicate the beginning of the predicted signal peptide and mature protein sequences of Ci-45, respectively. Sequence printed in bold was also obtained by N-terminal sequencing of the Ci-45 protein. (PNG 301 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM4_ESM.PNG

Additional file 4:Amino acid sequence alignment of Imaginal disc Growth Factors (IDGFs)-like proteins from different insect species. The sequence of the Ci-48b from C. inanitus was aligned with sequences from the following species: N. vitripennis [GenBank:XP_001599305.1], A. mellifera [GenBank:XP_396769.2] and Manduca sexta [GenBank:ACW82749.1]. The conserved region II is boxed. Triangle indicates a glutamine residue replacing, in these proteins, a glutamic acid residue of functional importance. Location of the glycosyl hydrolase family 18 domain is indicated by a blue line. Red and green arrows indicate the beginning of the predicted signal peptide and mature protein sequences of Ci-48b, respectively. Sequence printed in bold was also obtained by N-terminal sequencing of the Ci-48b protein. (PNG 274 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM5_ESM.PNG

Additional file 5:Amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-23c, Ci-220 and AD-873. The sequences of the Ci-23c and Ci-220 proteins from C. inanitus were aligned with the sequence of the AD-873 protein from Anopheles darlingi [GenBank:ACI30179.1]. Location of the chitin-binding Peritrophin-A (CBM_14) domains of Ci-23c are indicated by green lines under the alignment. Serine residues that potentially serve as glycosaminoglycan attachment sites are indicated by blue triangles. Red and green arrows indicate the beginning of the predicted signal peptide and mature protein sequences of Ci-23c, respectively. (PNG 73 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM6_ESM.PNG

Additional file 6:Partial amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-300 with insect metalloproteases. The sequence of Ci-300 was aligned with sequences of metalloproteases from the following species: N. vitripennis [NCBI Reference Sequence:XP_001604431.1] and [NCBI Reference Sequence: NP_001155006.1], P. hypochondriaca [GenBank:CAD21587.1] and E. pennicornis [GenBank:ACF60597.1]. The Zn2+-binding motif of HExxHxxGxxH featuring known metalloproteases' partial alignment is boxed in black. (PNG 39 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM7_ESM.PNG

Additional file 7:Amino acid sequence alignment of Ci-40a with serine protease homologs (SPHs). The partial sequence of Ci-40a was aligned with sequences of SPHs from the following species: A. mellifera [NCBI Reference Sequence:XP_623150.2], C. rubecula [GenBank:AAP49428.1], N. vitripennis [NCBI Reference Sequence:NP_001166254.1] and [NCBI Reference Sequence:NP_001155014.1] and A. aegypti [NCBI Reference Sequence:XP_001661226.1]. The location of the trypsin-like serine protease domain of Ci40a is indicated by a blue line under the alignment. (PNG 139 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM8_ESM.XLS

Additional file 8:Sequence similarities between Ci-48a, Vem17 and Ci-80b and proteins similar to isoforms of lethal (1) G0193. Sequences similarities were determined by comparing the amino acid sequences of Ci-48a, Vem17 and Ci-80 to protein sequences deposited in NCBI nr database using BLASTP algorithm. The percentage of identity and E-value are given for each comparison. E: embryo; n.d.: not determined; n.s.: no significant similarity found (E-value> 1e-04); SG: salivary gland; VG: venom gland. (XLS 10 KB)

12864_2010_10143_MOESM9_ESM.PNG

Additional file 9:Phylogeny of the major superfamilies of Hymenoptera. Family and species names discussed in the present paper are indicated on the right side of the figure. The phylogeny of Hymenoptera shown on the left side of the figure is adapted from [9]. (PNG 408 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vincent, B., Kaeslin, M., Roth, T. et al. The venom composition of the parasitic wasp Chelonus inanitus resolved by combined expressed sequence tags analysis and proteomic approach. BMC Genomics 11, 693 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-693

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-11-693