Abstract

Brain development is influenced by various prenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal events which may interact with genotype to affect the neural and psychophysiological systems related to emotions, specific cognitive functions (e.g., attention, memory), and language abilities and thereby heighten the risk for psychopathology later in life. Fetal hypoxia (intrapartum oxygen deprivation), hypoxia-related obstetric complications, and hypoxia during the early neonatal period are major environmental risk factors shown to be associated with an increased risk for later psychopathology. Experimental models of perinatal hypoxia/ischemia (PHI) showed that fetal hypoxia—a consequence common to many birth complications in humans—results in selective long-term disturbances of the dopaminergic systems that persist in adulthood. On the other hand, neurotrophic signaling is critical for pre- and postnatal brain development due to its impact on the process of neuronal development and its reaction to perinatal stress. The aim of this review is (a) to summarize epidemiological data confirming an association of PHI with an increased risk of a range of psychiatric disorders from childhood through adolescence to adulthood, (b) to present immunohistochemical findings on human autopsy material indicating vulnerability of the dopaminergic neurons of the human neonate to PHI that could predispose infant survivors of PHI to dopamine-related neurological and/or cognitive deficits in adulthood, and (c) to present and discuss older and recent findings on the differential expression of neurotrophins (BDNF, NGF, NT-3, and NT-4) in neonates following hypoxic/ischemic insults and its significance for the development of the human brain and the induction of psychopathology later in life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and epidemiological data

A complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors is intricately involved in brain development; therefore, any disruption of these factors is capable of impacting upon neuronal structure, function, and connectivity and can thus alter the natural stages of development. In turn, this can result in long-lasting and even permanent effects and conduce to psychiatric disorders [1]. A range of prenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal events are likely to contribute to neurodevelopment through interacting with the individual’s genotype to affect the neural and psychophysiological systems related to emotion, specific cognitive functions (e.g., attention, memory), and language abilities, thereby heightening the risk for develo** psychopathology later in life [2, 3].

Epidemiological studies indicated that fetal hypoxia (intrapartum oxygen deprivation), hypoxia-related obstetric complications, and hypoxia during the early neonatal period are among the biological environmental risk factors that have been hypothesized to play a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) [4,5,6]. Due to the great variety of causes inducing perinatal hypoxia, there are no published data on the overall incidence of perinatal hypoxic events. Estimates are quite variable depending on the definition used. De Haan et al. reported an incidence of perinatal asphyxia of 1 to 6 per 1000 live full-term births [7]. The overall incidence of fetal hypoxia/acidosis, however, as defined by the incidence of newborn metabolic acidosis, varies substantially between different European hospitals depending on the risk characteristics of the population and on labor management strategies. Reported rates based on newborn metabolic acidosis vary between 0.06 and 2.8% [8].

Early case-control studies involving patients with neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders and siblings or normal comparison groups have demonstrated a positive association between obstetric complications (OCs)/pregnancy and delivery complications (PDCs) and serious neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., cerebral palsy, epilepsy, intellectual disability) [9], autism [10], childhood and adult schizophrenia [11,12,13], and a possible association with cluster B (such as borderline or antisocial) personality disorders later in life [14]. Studies focusing on specific childhood syndromes indicated that disruptive behavior disorders, i.e., ADHD, conduct disorder, and oppositional disorder, were associated with OCs/PDCs [15]. However, this type of study design did not help to clarify whether the observed association between psychiatric disorders and OCs/PDCs points to a causative contribution (true risk factors) or represents an outcome associated with a primary abnormality in the genetically susceptible fetus. The use of a broadly defined single OCs index did not allow for differentiation between the effects of various OCs/PDCs and hence contributed to inconsistent findings [16].

Subsequent population-based cohort studies shed more light on this topic through differentiating between the effects of various OCs/PDCs and adjusting for potential confounders [17,18,19]. Findings from a large long-term prospective study from the prenatal period through age 7 years and age 18 to 27 years—which examined the hypothesis that PDCs result in increased risk for the development of psychiatric disorders—showed that chronic fetal hypoxia doubled the risk of develo** a psychotic disorder but failed to confirm prior reports of a positive association between either preterm birth or other PDCs and an adult psychiatric disorder [20]. Mild to severe cognitive impairment was associated with preterm birth as well as chronic fetal hypoxia. Subsequently, a study conducted by Cannon and colleagues (2000) found that the odds of schizophrenia increased linearly with the increasing number of hypoxia-associated obstetric complications and that this effect was specific to cases with an earlier age at onset [21]. Signs of asphyxia at birth were independently associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia, while the odds ratios were approximately the same when divided into slight (OR 2.6; 95% CI, 1.3–5.3) or moderate to severe asphyxia (OR 2.8; 95% CI, 1.0–7.4). Evidence of increased vulnerability to effects of fetal hypoxia was also found in the 1991–1992 UK birth cohort study [22], which examined the presence of non-clinical psychotic experiences during childhood. More specifically, the risk of develo** definite psychotic-like symptoms, which may increase the risk of develo** clinically important psychotic disorders later in life [23, 24], was associated with the need for resuscitation at birth (adjusted OR 1.50, 95% CI, 0.97–2.31) and a lower 5-min Apgar score (adjusted OR per unit decrease 1.30, 95% CI, 1.14–1.51). The Swedish population-based cohort study [25], using as an outcome measure hospitalization for adult-onset (age > 16 years) psychiatric disorders, addressed the issue of whether preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction, and delivery-related hypoxia, all associated with schizophrenia, also pertain to other adult-onset psychiatric disorders or whether these perinatal events are independent. The findings suggested that individuals with younger gestational age at birth (< 32 weeks) were 2.5 (95% CI, 1.0–6.0) times more likely to have a non-affective psychosis, 2.9 (95% CI, 1.8–4.6) times more likely to have depressive disorder and 7.4 (95% CI, 2.7–20.6) times more likely to have bipolar affective disorder. Similar associations were not observed for non-optimal fetal growth. With regard to delivery-related hypoxia, as indicated by a low 5-min Apgar score, only cases with a score of 3 or less were 2.2 (95% CI, 1.8–4.6) times more likely to have been hospitalized with depressive disorder and 3.8 (95% CI, 1.8–4.6) times more likely to have been hospitalized with bipolar affective disorder.

Fetal hypoxia places the develo** brain at risk and could thus increase the chance of develo** neuropsychiatric disorders that are diagnosed during early childhood, such as ASDs and ADHD [10]. A recent comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by Gardener, Spiegelman and Buka (2011) identified several perinatal risk factors, all associated with hypoxia before, during or immediately after birth, as increasing the risk of develo** ASD [26]. The increased odds ratios (3.0 or more) were found for neonatal anemia (OR 7.87, 95% CI, 1.43–43.36), meconium aspiration (OR 7.34, 95% CI 2.30–23.47), birth trauma (OR 4.90, 95% CI, 1.41–16.94), and very low (< 1.5 kg) birth weight (OR 3.0, 95% CI, 1.73–5.20). Although fetal hypoxia has not been proven as an independent risk factor for ASD, its plausible role in the trajectory towards develo** ASD needs to be clarified in future studies [10].

Adverse effects of perinatal obstetrical complications and prematurity have been shown to be associated with ADHD. A case-control study found higher rates of pregnancy, labor/delivery, and neonatal complications in children diagnosed with ADHD as compared to their unaffected siblings. Of particular interest was the finding that having received oxygen therapy—clearly indicating hypoxia during the first 2 months of life—increased the risk of develo** ADHD [27]. A recent nested case-control cohort study, using the Kaiser Permanente Southern California electronic medical records, indicated that exposure to perinatal hypoxia/ischemia (PHI), and in particular to birth asphyxia, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, and preeclampsia, was associated with a 16% greater risk of develo** ADHD. Specifically, exposure to birth asphyxia was associated with a 26% greater risk of develo** ADHD; exposure to neonatal respiratory distress syndrome was associated with a 47% greater risk, and exposure to preeclampsia was associated with a 34% greater risk. The increased risk of ADHD remained the same across all race and ethnicity groups [28].

The role of perinatal hypoxia in human brain dopamine neurotransmission

Since dopaminergic mechanisms are central to both ADHD [29] and schizophrenia pathophysiology [30, 31], the effect of perinatal hypoxia on dopamine neurotransmission was studied in the human neonatal brain at autopsy [32, 33] as well as in experimental animals from birth to adulthood [34,35,36,37]. Animal models of PHI showed that hypoxic/ischemic lesions can cause selective long-term changes to the central dopaminergic systems that persist into adulthood [34, 36, 38]. The substantia nigra (SN) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the mesencephalon contain the majority of dopaminergic neurons in the brain and are heavily involved in the control of motor and cognitive behaviors.

Studies on human autopsy material showed that PHI—depending on its severity/duration—differentially affects the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate the synthesis of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of dopamine synthesis, in different catecholaminergic brain nuclei [32, 39,40,41,42]. TH is an oxygen-requiring enzyme, and kinetic properties suggest that oxygen availability may limit the synthesis of catecholamines in the brain [43]. TH, however, loses its oxygen dependency during physical stress, indicating that substrate limitation can be overcome when the neuronal needs for the neurotransmitter are increased [43, 44]. Hypoxia is a major regulator of TH gene expression. Several transcription factors that are activated by hypoxic conditions (e.g., hypoxia inducible factor-HIF-1) can regulate both the rate of TH expression and TH mRNA stability [45, 46]. Interestingly, Schmidt-Kastner and colleagues found that 55% of schizophrenia candidate genes are regulated by hypoxia and/or expressed in the vascular system [47].

The mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons of the neonate are especially vulnerable to prolonged PHI [32], as indicated by immunohistochemistry on postmortem material of the SN and VTA obtained at autopsy of 16 full-term and two preterm neonates after parental written consent (Greek Brain Bank, directed by Professor of Pathology University of Athens, E. Patsouris). The estimation of the severity/duration of the PHI injury was based on established neuropathological criteria [48,49,50], taking into consideration the regional aspects of neuronal necrosis [39] (performed by perinatal pathologist, Prof. A. Konstantinidou).

In neonates with neuropathological signs of abrupt PHI injury, intense TH-immunoreactivity was found in the SN and VTA [32]. Interestingly, increased TH-immunoreactivity and increased in vivo synthesis of dopamine have been reported in the SN of patients with schizophrenia using neuroimaging techniques [31]. In neonates who suffered an abrupt PHI however, TH expression was also observed in neurons synthesizing urocortin-1 (a stress peptide belonging to the corticotropin-releasing factor family) of the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, a nucleus not previously known for its dopaminergic phenotype [32, 42]. Edinger-Westphal plays a significant role in stress response and, therefore, in stress-related disorders like anxiety and major depression, as well as in regulation of food and water intake and the use of alcohol and drugs of abuse.

In the same sample, neonates with neuropathological changes of prolonged or older PHI damage showed a striking reduction of TH-immunoreactivity in the mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons, pointing to possible early dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission under prolonged hypoxic conditions. SN neurons were found to be of a significantly smaller size in the above cases compared to those of neonates with acute PHI injury [32], raising the question whether this significant decrease in both their size and their ability to synthesize dopamine reflects an early stage of degeneration or a developmental delay of dopaminergic neurons. Abnormal maturation of the SN has been described in ADHD [51], while a substantial reduction in the volume of the nigrostriatal area accompanied by a decreased size of SN neurons has been reported in schizophrenia [52]. Degeneration of the SN and inhibition of dopamine synthesis are the main neuropathological findings in Parkinson’s disease [53].

The results of studies investigating the human mesencephalon are in agreement with experimental data indicating that PHI causes duration-dependant changes in the number of the dopaminergic neurons in the SN and VTA as well as in DA neurotransmission in their target areas (summarized in Table 1). An increased number of dopaminergic neurons were observed in the SN and VTA of the rat after a brief perinatal hypoxic insult [34, 37]. Unilateral hypoxic/ischemic injury in the neonatal rat resulted in a persistent increase in the density of striatal TH immunoperoxidase staining in the ipsilateral site [54]. In addition, perinatal hypoxia induced structural changes in the develo** brain, i.e., shrinkage of the hippocampus and the superimposing frontal cortex in the ipsilateral site as well as ventricular enlargement. Similar structural abnormalities (i.e., reduction of the brain volume in the hippocampus/prefrontal cortex and ventricular enlargement) accompanied by abnormal dopaminergic neurotransmission) are repeatedly reported in individuals suffering from schizophrenia [55,56,57] or ADHD [58,59,60].

Since experimental studies have shown that PHI can cause long-lasting alterations in the central dopaminergic systems that persist into adulthood [36, 38], we considered that dysfunction of dopaminergic systems in the early developmental stages can predispose the survivors of PHI to dopamine-related neurological and neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders later in life [32, 61]. Dopamine-mediated signaling plays a fundamental neurodevelopmental role in forebrain differentiation and circuit formation. These developmental effects, such as modulation of neuronal migration and dendritic growth, occur before synaptogenesis and demonstrate novel roles for dopaminergic signaling beyond neuromodulation at the synapse [1].

The role of perinatal hypoxia in neurotrophin signaling

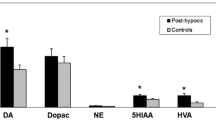

Dopamine—as well as other neurotransmitter systems reported to be dysregulated by perinatal hypoxia in experimental animals, such as serotonin [62] and noradrenaline [63]—express their developmental roles partially through their interaction with neurotrophins [64, 65]. Recent emerging evidence suggests disrupted neurotrophic signaling in response to perinatal hypoxia in the molecular pathogenesis of later psychopathology, possibly indicating neurotrophins as novel molecular targets for preventive intervention [66,67,68,69]. Thus, neurotrophins are currently prominent candidates for mediating the relationship between perinatal hypoxia and psychopathology due to their critical role in protecting against neuronal damage following adverse intrauterine events [70], their documented dysregulation in neuropsychiatric disorders [66, 69], and their abnormal expression in response to fetal hypoxia [67].

Members of the neurotrophin family, including the nerve growth factor (NGF), the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) play a fundamental role in brain function and neuroprotection [71]. They are important for axon growth, higher neuronal functions, developmental maturity of the cortex, and synaptic plasticity, leading to refinement of connections, morphologic differentiation, and neurotransmitter expression [71]. Νeurotrophic factors play crucial roles in neuroprotection by promoting survival and by reducing apoptosis in many neuronal populations [71, Money KM, Stanwood GD (2013) Developmental origins of brain disorders: roles for dopamine. Front Cell Neurosci 7:260 Rutter M, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (2006) Gene-environment interplay and psychopathology: multiple varieties but real effects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:226–261 Taylor E, Rogers JW (2005) Practitioner review: early adversity and developmental disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46:451–467 Cannon TD, van Erp TG, Rosso IM et al (2002) Fetal hypoxia and structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenic patients, their siblings, and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:35–41 DeLong GR (1992) Autism, amnesia, hippocampus, and learning. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 16:63–70 Lou HC (1996) Etiology and pathogenesis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): significance of prematurity and perinatal hypoxic-haemodynamic encephalopathy. Acta Paediatr 85:1266–1271 de Haan M, Wyatt JS, Roth S, Vargha-Khadem F, Gadian D, Mishkin M (2006) Brain and cognitive-behavioural development after asphyxia at term birth. Dev Sci 9:350–358 Ayres-de-Campos D (2017) In: Ayres-de-Campos D (ed) Obstetric emergencies: a practical guide. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland Nelson KB, Ellenberg JH (1984) Obstetric complications as risk factors for cerebral palsy or seizure disorders. JAMA 251:1843–1848 Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A (2007) Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism: a review and integration of findings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161:326–333 Geddes JR, Lawrie SM (1995) Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 167:786–793 Geddes JR, Verdoux H, Takei N et al (1999) Schizophrenia and complications of pregnancy and labor: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 25:413–423 Verdoux H, Geddes JR, Takei N et al (1997) Obstetric complications and age at onset in schizophrenia: an international collaborative meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Psychiatry 154:1220–1227 Dahl A, Boerdahl P (1993) Obstetric complications as a risk factor for subsequent development of personality disorders. J Pers Dis 7:22–27 Latimer K, Wilson P, Kemp J et al (2012) Disruptive behaviour disorders: a systematic review of environmental antenatal and early years risk factors. Child Care Health Dev 38:611–628 Cannon M, Jones PB, Murray RM (2002) Obstetric complications and schizophrenia: historical and meta-analytic review. Am J Psychiatry 159:1080–1092 Dalman C, Allebeck P, Cullberg J, Grunewald C, Koster M (1999) Obstetric complications and the risk of schizophrenia: a longitudinal study of a national birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:234–240 Done DJ, Johnstone EC, Frith CD, Golding J, Shepherd PM, Crow TJ (1991) Complications of pregnancy and delivery in relation to psychosis in adult life: data from the British perinatal mortality survey sample. BMJ 302:1576–1580 Rosso IM, Cannon TD, Huttunen T, Huttunen MO, Lonnqvist J, Gasperoni TL (2000) Obstetric risk factors for early-onset schizophrenia in a finnish birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry 157:801–807 Buka SL, Tsuang MT, Lipsitt LP (1993) Pregnancy/delivery complications and psychiatric diagnosis. A prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:151–156 Cannon TD, Rosso IM, Hollister JM, Bearden CE, Sanchez LE, Hadley T (2000) A prospective cohort study of genetic and perinatal influences in the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 26:351–366 Zammit S, Odd D, Horwood J et al (2009) Investigating whether adverse prenatal and perinatal events are associated with non-clinical psychotic symptoms at age 12 years in the alspac birth cohort. Psychol Med 39:1457–1467 Hanssen M, Bak M, Bijl R, Vollebergh W, van Os J (2005) The incidence and outcome of subclinical psychotic experiences in the general population. Br J Clin Psychol 44:181–191 Zammit S, Kounali D, Cannon M et al (2013) Psychotic experiences and psychotic disorders at age 18 in relation to psychotic experiences at age 12 in a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Am J Psychiatry 170:742–750 Nosarti C, Reichenberg A, Murray RM et al (2012) Preterm birth and psychiatric disorders in young adult life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:E1–E8 Gardener H, Spiegelman D, Buka SL (2011) Perinatal and neonatal risk factors for autism: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Pediatrics 128:344–355 Ben Amor L, Grizenko N, Schwartz G et al (2005) Perinatal complications in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected siblings. J Psychiatry Neurosci 30:120–126 Getahun D, Rhoads GG, Demissie K et al (2012) In utero exposure to ischemic-hypoxic conditions and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 131:e53–e61 Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Makris N (2005) Structural brain imaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 57:1263–1272 Howes OD, Kapur S (2009) The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version iii—the final common pathway. Schizophr Bull 35:549–562 Howes OD, Williams M, Ibrahim K et al (2013) Midbrain dopamine function in schizophrenia and depression: a post-mortem and positron emission tomographic imaging study. Brain 136:3242–3251 Pagida MA, Konstantinidou AE, Tsekoura E, Mangoura D, Patsouris E, Panayotacopoulou MT (2013) Vulnerability of the mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons of the human neonate to prolonged perinatal hypoxia: an immunohistochemical study of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in autopsy material. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72:337–350 Panayotacopoulou MT, Swaab DF (1993) Development of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive neurons in the human paraventricular and supraoptic nucleus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 72:145–150 Bjelke B, Andersson K, Ogren SO, Bolme P (1991) Asphyctic lesion: proliferation of tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive nerve cell bodies in the rat substantia nigra and functional changes in dopamine neurotransmission. Brain Res 543:1–9 Brake WG, Boksa P, Gratton A (1997) Effects of perinatal anoxia on the acute locomotor response to repeated amphetamine administration in adult rats. Psychopharmacology 133:389–395 Burke RE, Macaya A, DeVivo D, Kenyon N, Janec EM (1992) Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic or excitotoxic striatal injury results in a decreased adult number of substantia nigra neurons. Neuroscience 50:559–569 Chen Y, Herrera-Marschitz M, Bjelke B, Blum M, Gross J, Andersson K (1997) Perinatal asphyxia-induced changes in rat brain tyrosine hydroxylase-immunoreactive cell body number: effects of nicotine treatment. Neurosci Lett 221:77–80 Boksa P, El-Khodor BF (2003) Birth insult interacts with stress at adulthood to alter dopaminergic function in animal models: possible implications for schizophrenia and other disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27:91–101 Pagida MA, Konstantinidou AE, Korelidou A et al (2016) The effect of perinatal hypoxic/ischemic injury on tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the locus coeruleus of the human neonate. Dev Neurosci 38:41–53 Ganou V, Pagida MA, Konstantinidou AE et al (2010) Increased expression of tyrosine hydroxylase in the supraoptic nucleus of the human neonate under hypoxic conditions: a potential neuropathological marker for prolonged perinatal hypoxia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69:1008–1016 Pagida MA, Konstantinidou AE, Malidelis YI et al (2013) The human neurosecretory neurones under perinatal hypoxia: a quantitative immunohistochemical study of the supraoptic nucleus in autopsy material. J Neuroendocrinol 25:1255–1263 Pagida MA, Konstantinidou AE, Tsekoura E, Patsouris E, Panayotacopoulou MT (2013) Immunohistochemical demonstration of urocortin 1 in edinger-westphal nucleus of the human neonate: colocalization with tyrosine hydroxylase under acute perinatal hypoxia. Neurosci Lett 554:47–52 Davis JN (1976) Brain tyrosine hydroxylation: alteration of oxygen affinity in vivo by immobilization or electroshock in the rat. J Neurochem 27:211–215 Feinsilver SH, Wong R, Raybin DM (1987) Adaptations of neurotransmitter synthesis to chronic hypoxia in cell culture. Biochim Biophys Acta 928:56–62 Czyzyk-Krzeska MF, Beresh JE (1996) Characterization of the hypoxia-inducible protein binding site within the pyrimidine-rich tract in the 3′-untranslated region of the tyrosine hydroxylase mrna. J Biol Chem 271:3293–3299 Paulding WR, Schnell PO, Bauer AL et al (2002) Regulation of gene expression for neurotransmitters during adaptation to hypoxia in oxygen-sensitive neuroendocrine cells. Microsc Res Tech 59:178–187 Schmidt-Kastner R, van Os J, Esquivel G, Steinbusch HW, Rutten BP (2012) An environmental analysis of genes associated with schizophrenia: hypoxia and vascular factors as interacting elements in the neurodevelopmental model. Mol Psychiatry 17:1194–1205 Fallet-Bianco C (2005) Diagnosis and dating of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy 20th European congress of pathology. France, Paris, pp 127–132 Rorke-Adams L, Larroche J, de Vries L (2007) Fetal and neonatal brain damage. In: Gilbert-Barness E (ed) Potter’s pathology of the fetus, infant and child. Mosby- Elsevier, Philadelphia, pp 2027–2053 Squier W (2004) Gray matter lesions. In: Golden J, Harding B (eds) Pathology and genetics, developmental neuropathology. ISN Neuropathology Press, Basel, pp 171–175 Romanos M, Weise D, Schliesser M et al (2010) Structural abnormality of the substantia nigra in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci 35:55–58 Bogerts B, Hantsch J, Herzer M (1983) A morphometric study of the dopamine-containing cell groups in the mesencephalon of normals, parkinson patients, and schizophrenics. Biol Psychiatry 18:951–969 Cacabelos R (2017) Parkinson’s disease: from pathogenesis to pharmacogenomics. Int J Mol Sci 18:551–578 Burke RE, Kent J, Kenyon N, Karanas A (1991) Unilateral hypoxic-ischemic injury in neonatal rat results in a persistent increase in the density of striatal tyrosine hydroxylase immunoperoxidase staining. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 58:171–179 Mittal VA, Ellman LM, Cannon TD (2008) Gene-environment interaction and covariation in schizophrenia: the role of obstetric complications. Schizophr Bull 34:1083–1094 Miyamoto S, LaMantia AS, Duncan GE, Sullivan P, Gilmore JH, Lieberman JA (2003) Recent advances in the neurobiology of schizophrenia. Mol Interv 3:27–39 Van Erp TG, Saleh PA, Rosso IM et al (2002) Contributions of genetic risk and fetal hypoxia to hippocampal volume in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, their unaffected siblings, and healthy unrelated volunteers. Am J Psychiatry 159:1514–1520 Curatolo P, Paloscia C, D’Agati E, Moavero R, Pasini A (2009) The neurobiology of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 13:299–304 Tripp G, Wickens JR (2009) Neurobiology of ADHD. Neuropharmacology 57:579–589 Prince J (2008) Catecholamine dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. J Clin Psychopharmacol 28(Suppl 2):39–45 Barlow BK, Cory-Slechta DA, Richfield EK, Thiruchelvam M (2007) The gestational environment and Parkinson’s disease: evidence for neurodevelopmental origins of a neurodegenerative disorder. Reprod Toxicol 23:457–470 Reinebrant HE, Wixey JA, Buller KM (2013) Neonatal hypoxia-ischaemia disrupts descending neural inputs to dorsal raphe nuclei. Neuroscience 248C:427–435 Buller KM, Wixey JA, Pathipati P et al (2008) Selective losses of brainstem catecholamine neurons after hypoxia-ischemia in the immature rat pup. Pediatr Res 63:364–369 Homberg JR, Molteni R, Calabrese F, Riva MA (2014) The serotonin-BDNF duo: developmental implications for the vulnerability to psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 43:35–47 Kuppers E, Beyer C (2001) Dopamine regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression in cultured embryonic mouse striatal cells. Neuroreport 12:1175–1179 Autry AE, Monteggia LM (2012) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol Rev 64:238–258 Cannon TD, Yolken R, Buka S, Torrey EF (2008) Decreased neurotrophic response to birth hypoxia in the etiology of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 64:797–802 Casey BJ, Glatt CE, Tottenham N et al (2009) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a model system for examining gene by environment interactions across development. Neuroscience 164:108–120 Shoval G, Weizman A (2005) The possible role of neurotrophins in the pathogenesis and therapy of schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15:319–329 Husson I, Rangon CM, Lelievre V et al (2005) BDNF-induced white matter neuroprotection and stage-dependent neuronal survival following a neonatal excitotoxic challenge. Cereb Cortex 15:250–261 Hennigan A, O’Callaghan RM, Kelly AM (2007) Neurotrophins and their receptors: roles in plasticity, neurodegeneration and neuroprotection. Biochem Soc Trans 35:424–427 Hetman M, **a Z (2000) Signaling pathways mediating anti-apoptotic action of neurotrophins. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars) 60:531–545 Karege F, Schwald M, Cisse M (2002) Postnatal developmental profile of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rat brain and platelets. Neurosci Lett 328:261–264 Cirulli F, Francia N, Berry A, Aloe L, Alleva E, Suomi SJ (2009) Early life stress as a risk factor for mental health: role of neurotrophins from rodents to non-human primates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:573–585 Cirulli F, Berry A, Alleva E (2003) Early disruption of the mother-infant relationship: effects on brain plasticity and implications for psychopathology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27:73–82 Rao R, Mashburn CB, Mao J, Wadhwa N, Smith GM, Desai NS (2009) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in infants <32 weeks gestational age: correlation with antenatal factors and postnatal outcomes. Pediatr Res 65:548–552 Chouthai NS, Sampers J, Desai N, Smith GM (2003) Changes in neurotrophin levels in umbilical cord blood from infants with different gestational ages and clinical conditions. Pediatr Res 53:965–969 Malamitsi-Puchner A, Economou E, Rigopoulou O, Boutsikou T (2004) Perinatal changes of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in pre- and full-term neonates. Early Hum Dev 76:17–22 Nikolaou KE, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Boutsikou T et al (2006) The varying patterns of neurotrophin changes in the perinatal period. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1092:426–433 Bernd P (2008) The role of neurotrophins during early development. Gene Expr 14:241–250 Kawamura K, Kawamura N, Kumazawa Y, Kumagai J, Fujimoto T, Tanaka T (2011) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor/tyrosine kinase b signaling regulates human trophoblast growth in an in vivo animal model of ectopic pregnancy. Endocrinology 152:1090–1100 Mayeur S, Lukaszewski MA, Breton C, Storme L, Vieau D, Lesage J (2011) Do neurotrophins regulate the feto-placental development? Med Hypotheses 76:726–728 Korhonen L, Riikonen R, Nawa H, Lindholm D (1998) Brain derived neurotrophic factor is increased in cerebrospinal fluid of children suffering from asphyxia. Neurosci Lett 240:151–154 Miller FD, Kaplan DR (2001) Neurotrophin signalling pathways regulating neuronal apoptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 58:1045–1053 Eide MG, Moster D, Irgens LM, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Stoltenberg C, Skjaerven R, Susser E, Abel K (2013) Degree of fetal growth restriction associated with schizophrenia risk in a national cohort. Psychol Med 43:2057–2066 Van Lieshout RJ, Voruganti LP (2008) Diabetes mellitus during pregnancy and increased risk of schizophrenia in offspring: a review of the evidence and putative mechanisms. J Psychiatry Neurosci 33:395–404 Coupe B, Dutriez-Casteloot I, Breton C et al (2009) Perinatal undernutrition modifies cell proliferation and brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels during critical time-windows for hypothalamic and hippocampal development in the male rat. J Neuroendocrinol 21:40–48 Ninomiya M, Numakawa T, Adachi N et al (2010) Cortical neurons from intrauterine growth retardation rats exhibit lower response to neurotrophin BDNF. Neurosci Lett 476:104–109 Malamitsi-Puchner A, Nikolaou KE, Economou E et al (2007) Intrauterine growth restriction and circulating neurotrophin levels at term. Early Hum Dev 83:465–469 Mayeur S, Silhol M, Moitrot E et al (2010) Placental BDNF/TRKB signaling system is modulated by fetal growth disturbances in rat and human. Placenta 31:785–791 Briana DD, Papastavrou M, Boutsikou M, Marmarinos A, Gourgiotis D, Malamitsi-Puchner A (2017) Differential expression of cord blood neurotrophins in gestational diabetes: The impact of fetal growth abnormalities. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med:1–6 Boersma GJ, Lee RS, Cordner ZA et al (2014) Prenatal stress decreases BDNF expression and increases methylation of BDNF exon iv in rats. Epigenetics 9:437–447 Kundakovic M, Gudsnuk K, Herbstman JB, Tang D, Perera FP, Champagne FA (2015) DNA methylation of BDNF as a biomarker of early-life adversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:6807–6813References

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

About this article

Cite this article

Giannopoulou, I., Pagida, M.A., Briana, D.D. et al. Perinatal hypoxia as a risk factor for psychopathology later in life: the role of dopamine and neurotrophins. Hormones 17, 25–32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-018-0007-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42000-018-0007-7