Abstract

Courses that target wellbeing have grown in higher education. Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs), the empirically validated activities designed to generate wellbeing, form the bulk of these courses. Their effectiveness has been documented across global meta-analyses; but less so in the Middle East/North Africa region and in classroom settings. Given the stigma of mental health, we developed and evaluated a happiness and wellbeing course to determine whether it could yield greater wellbeing in the United Arab Emirates. A semester-long happiness and wellbeing course (i.e., positive psychology) offering weekly PPIs was evaluated against pre- and post measures of subjective wellbeing, positive and negative emotion, a fear of happiness, locus of control, individualism and collectivism, somatic symptoms and stress. Only a statistically significant decrease in participant’s fear of happiness was recorded; no other impact was evident. PPIs, while normally effective, may be less so in raising wellbeing in a classroom setting where academic pressures may conflict with necessary insight and growth. Alternatively, it may be that these interventions are less effective in non-Western contexts where happiness and wellbeing are not considered urgent or essential goals, and where distress and wellbeing may co-exist more comfortably. Thus, despite such courses being of great interest in popular discourse and regularly used to support government agendas and institutional initiatives, they may not always be impactful routes to building the wellbeing of young people in higher education. More critical assessment of their outcomes and further study into how they can be better adapted for regional audiences is the way forward.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

University is a time of transition. Young people face new challenges in making independent decisions, adjusting to heavier academic demands, relying on fewer supports, and for some, leaving home for the first time. Indeed, mental health is taxed upon entrance and does not revert to pre-entry levels (Auerbach et al., 2018; Macaskill, 2013). Depression, anxiety, and stress are common across the university experience and tend to peak around the age of 25 (Auerbach et al., 2018; Colizzi et al., 2020; Solmi et al., 2021; Sweileh, 2021a), making institutions ideal spaces in which to provide wellbeing and mental health services. This is especially the case across the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region, where mental health is stigmatized and poorly resourced (Maalouf et al., 2019; Sweileh, 2021a). Yet, wellbeing is not limited to mitigating poor mental health, it also addresses positive outcomes. Positive psychology interventions (PPIs), strategies to improve wellbeing, are one such strategy, with many combined into for-credit university courses. Here, we review the outcomes of a university-based happiness and wellbeing course in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

1 Mental Health in the MENA Region

Charara et al. (2018) examined the MENA region, showing that depression and anxiety were the third and ninth leading cause of burden of disease, with almost all countries having higher burdens than global levels. More localized in the Gulf region, Chan et al. (2021) calculated pooled prevalence rates, estimating that depression stood between 26% and 46% (depending on the measures used), anxiety between 17% and 57%, and stress at 43% in the region’s young adults, noting the upper limits of these estimates to be above international rates. As half of the region is under the age of 18 (Alkhamees et al., 2020; GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Mental Health Collaborators, 2018), offerings are vital, particularly in higher educational settings, where many young people end up. Yet, insufficient capacity, low mental health literacy and stigma in both users and providers undermine the region’s ability to build positive psychological capabilities (Eissa et al., 2020; Elyamani et al., 2021; Maalouf et al., 2019; Sweileh, 2021b). To counter these, a focus on wellbeing promoted by positive psychology may serve to prevent and treat mental illness, as well as promote wellbeing in the absence of services, and in higher education more specifically (Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020; Hobbs et al., 2022; Waters et al., 2021).

2 Positive Psychology in Higher Education

The dissemination and use of positive psychology strategies is now a global phenomena (Hendriks, Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018). In fact, this expansion has moved into higher education and includes the offer of academic courses in the science of wellbeing, where theoretical content as well as training in the skills leading to a good life are offered as credit-bearing advantages. While early renditions of such courses did not assess impact (i.e., Bridges et al., 2012; Kim-Prieto & D’Oriano, 2011; Russo-Netzer & Ben-Shahar, 2011; Thomas & McPherson, 2011), more recent offerings have (i.e., Goodmon et al., 2016; Hobbs et al., 2022; Hood et al., 2021; Lefevor et al., 2018; Morgan & Simmons 2021; Yaden et al., 2021; Young et al., 2020). For example, Goodmon et al. (2016) showed returns in the form of life satisfaction, fewer depressive symptoms and less stress, while Young et al. (2020) showed improvements in positive affect, lower negative affect, stress, and other clinical categories relative to controls. Hood et al. (2021) also showed positive effects in mental wellbeing, life satisfaction and lower loneliness, including during online “pandemic” versions. Likewise, Yale’s ‘Science of Well-Being’ also evidenced greater subjective wellbeing (Yaden et al., 2021), while the latest study to be released (Hobbs et al., 2022) showed much the same.

These findings are important not only for curricula’s sake but for wellbeing outcomes. For instance, research suggests that the absence of wellbeing predicts depression (Wood & Joseph, 2010) and its presence is protective against mental health issues (Layous et al., 2014; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Shin & Lyubomirsky, 2016). Indeed, meta-analyses show that PPIs increase wellbeing and reduce depressive symptoms up to 12 months in both normal and clinical groups (Bolier et al., 2013; Carr et al., 2020; Chakhssi et al., 2018; Fischer et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020; Hoppen & Morina, 2021; Koydemir et al., 2021; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009; van Agteren et al., 2021; White et al., 2019). Yet, while positive psychology grows in the Middle East region (e.g., Bassurah et al., 2021, 2022; Rao et al., 2015; Rashid & Al Haj Baddar, 2019), studies are limited to those evaluating the effects of stand-alone PPI programs delivered in the classroom (i.e., Lambert et al., 2019; Lambert, Passmore, Scull et al., 2019; Lambert, Warren et al., 2021), rather than longer for-credit university courses. Nonetheless, a recent review by Basurra et al. (2021; 2022) of regional PPI studies concluded that these were as effective in the region as elsewhere.

3 Wellbeing in a Cultural Context

Despite their success, PPIs may be affected by culture. Positive psychology holds Western notions of individualism, which act on an autonomous self, i.e., self-efficacy, self-esteem, self-compassion, self-worth (Foody et al., 2013; Hendriks, Warren et al., 2018; Wong & Roy, 2017). Individualistic nations tend to emphasize personal pleasures, independence, and control, while collectivistic cultures focus on familial and social obligations as well as interdependency (Ahuvia, 2002; Shin & Lyubomirsky, 2017; Uchida & Ogihara 2012). In individualistic contexts, happiness stems from one’s accomplishments and personal development, while collectivist cultures construe happiness via belonging and connectedness (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2014; Uchida & Ogihara 2012; Uchida & Oishi, 2016). Accordingly, collectivistic lifestyles often promote emotional moderation and the downregulation of positive affect as collective wellbeing - versus individual emotional expression - is more greatly prized (Joshanloo & Weijers, 2013). Few studies have examined the role of culture in PPI use, other than to suggest that some focus on strengthening the self, while others are oriented towards serving others (Boehm et al., 2011; Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2014; Lyubomirsky & Layous 2013). Only one UAE-based study examined cultural implications, finding that levels of individualism remained unchanged after using a mix of self and other focused PPIs (Lambert, Warren et al., 2021).

A fear of happiness (Joshanloo et al., 2015) may also impact PPI use and efficacy. More common in Islamic cultures, as well as more collectivistic and hierarchical nations, it is sometimes believed that happiness calls forth the evil eye and easily enables sin, with positive emotions being shunned as a result (Joshanloo et al., 2014). A belief in the fragility of happiness, the perception that happiness is controlled by, and subject to a higher power (Joshanloo et al., 2015), also contributes to how and whether individuals pursue and experience happiness. Both constructs were found in the UAE influencing levels of happiness themselves (Lambert, Draper et al., 2021), but modifiable to change via a six-week PPI program (Lambert et al., 2019). Given these notions, as well as suggestions to further unearth the mechanisms influencing and sha** wellbeing (van Zyl et al., 2019), we explore the impact of a for-credit university course in happiness and wellbeing in the UAE.

4 The Present Study

The purpose of this study was to (1) evaluate changes in student wellbeing after participating in a semester-long happiness and wellbeing course and (2) examine the impact of the course on locus of control, cultural orientation, as well as somatic symptoms and stress. We hypothesized that the wellbeing course would improve student wellbeing and have an impact on the latter variables.

5 Method

5.1 Participants

Classes took place from January to May of 2019. Ethics approval was granted (ERS_2018_5811) by the host institution. Four instructors used a standardized teaching manual that came with scripts, video links, reading material, instructions and templates for activities and assessments. Initially, weekly check-ins with instructors took place, but tapered off after a few weeks as they grew familiar with the expected tone and experiential nature of the course. Students took the course as a free elective and came from a range of programs.

5.2 Missing Values

There was a total of 129 responses to the pre-test survey and 142 responses to the post-test. Cases were excluded if they responded to less than 80% of the items on the first (n = 5) or second (n = 6) survey. Of the remaining cases, only two had any missing values; however, both were later dropped due to not meeting other inclusion criteria.

5.3 Survey Submission Dates

Students were able to respond to the initial survey during the semester beginning January 13. We removed four responses that were submitted after January 31. Of the remaining responses, most (n = 94) were submitted from January 13–16, with the remaining (n = 43) responses trickling in until January 29. Responses to the follow-up survey were received from April 23 to May 17.

5.4 Participant Identification

Participants were given instructions on how to create a unique identifier. We omitted cases due to problems with their identifier after drop** cases due to missing values or late submissions. If a duplicate identifier appeared in either the initial or follow-up survey, all but the first submission were dropped. This resulted in one case being dropped from the initial survey and eight cases being dropped from the follow-up survey. Finally, we removed cases from the initial survey without a matching identifier at each measurement occasion (n = 28).

5.5 Participant Characteristics

After exclusions, the final sample comprised 87 participants. They were predominantly women (n = 63). They were aged 18–20 (n = 58), 21–23 (n = 22), 24–30 years (n = 6), or over 30 (n = 1). Most were Emirati nationals (n = 74). The remaining identified their nationality as Omani (n = 4), Palestinian (n = 2), and Kenyan, Jordanian, Canadian, Comorian, American, Sudanese, or Pakistani. All undergraduates, students had been in the university for one year (n = 17), two years (n = 25), three years (n = 21), four years (15), and five or more (n = 9). Respondents were enrolled in a course taught by one of four different professors, with the proportions in each class being: 44%, 28%, 20%, and 8%.

5.6 Measures

A total of eight scales were given in English, the language of instruction at the institution. Cronbach’s alpha of each scale at both measurement occasions are presented in Table 1.

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) is a 5-item measure assessing one’s judgment of satisfaction with life as a whole. Examples include, “I am satisfied with my life” and “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life.” These are rated on a 7-point scale with end points of 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Items are added together for a final score and range from 5 to 35, with the neutral point at 20. The SWLS has high internal consistency (α > 0.79), while test-retest reliability and convergent validity is also high (Pavot & Diener, 1993).

The Academic Locus of Control Scale (Trice, 1985) targets university students in a 28-item true/false format and assesses the extent to which their academic locus of control (LOC) is internally or externally oriented. Item examples include, “I have largely determined my own career goals” and “Professors sometimes make an early impression of you and then no matter what you do‚ you cannot change that impression”. Scores range from 0 (internal LOC) to 28 (external LOC). It correlates well with other scales (Trice et al., 1987) and has high test-retest reliability.

Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al., 2009, 2010). The 12-item scale measures six positive (SPANE-P) (i.e., “pleasant”, “happy”, “joyful”), six negative feelings (SPANE-N) (i.e., “bad”, “angry”, “afraid”), and the balance between the two (SPANE-B). With good reliability and validity (Diener et al., 2010), high factor loadings, and strong construct validity, it also has moderate to very high correlations with other wellbeing measures.

Fear of Happiness Scale (FHS; Joshanloo et al., 2014). The five-item scale captures the stable belief that happiness is a sign of impending unhappiness. Example items include, “Disasters often follow good fortune” and “Having lots of joy and fun causes bad things to happen”. It is validated across multiple national groups and has good statistical properties (Joshanloo et al., 2014, 2015).

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) is a 10-item scale measuring the perception of stress currently and in the past month, and the degree to which situations are appraised as unpredictable/uncontrollable. Items are rated from 0 (Never) to 4 (Very Often) and include as examples, “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?” and “…how often have you felt that things were going your way?” A review by Lee (2012) confirms its statistical properties.

The Somatic Symptom Scale − 8 (SSS-8; Gierk et al., 2014) assesses somatic symptom burden across eight items. Respondents rate how much they are bothered by symptoms such as stomach or bowel problems, back pain, headaches, or feeling tired in the last seven days on a 5-point scale. The SSS-8 has high internal consistency and content validity (Gierk et al., 2014).

Mental Health Continuum - Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes 2009). The 14-item scale measures social (integration/contribution), emotional (positive emotion/satisfaction with life), and psychological (autonomy/personal growth) wellbeing. Respondents respond to items asking how many times in the last 30 days they felt that “people are basically good”, “the way society works made sense to you” and “you like most parts of your personality.” Validated across cultural contexts (Joshanloo et al., 2013), it has good test-retest reliability (Lamers et al., 2012). Diagnoses range from flourishing (upper limits), languishing (lower limits), and moderate mental health.

Individualism and Collectivism Scale (ICS; Triandis & Gelfland 1998): This 16-item measure captures four subscales including, vertical (VC) or horizontal (HC) collectivism (i.e., seeing the self as part of a group and willing to accept hierarchy and inequality or perceiving all members as equal), as well as vertical (VI) or horizontal (HI) individualism (seeing the self as independent and accepting of inequality or that equality is the norm). Item examples for each subscale included: HI (“I rely on myself most of the time; I rarely rely on others”); VI (“Winning is everything”); HC (“I feel good when I cooperate with others”); VC (“It is my duty to take care of my family, even when I have to sacrifice what I want”). Cronbach’s α are 0.81 (HI), 0.82 (VI), 0.80(HC), 0.73(VC).

5.7 Procedure

Students completed the survey measures online via SurveyMonkey in the first month of class and at the end of term. Weekly themes (Table 2) are shown with the associated PPIs. Theory, concepts, and relevant research literature in positive psychology was explored and learning was supplemented by readings, videos, discussion, weekly reflection assignments, and a final project.

6 Results

6.1 Analytic Strategy

The effectiveness of the intervention was tested by comparing mean scores between measurement occasions, using paired samples t tests. Consistent with our hypothesis that the intervention would improve wellbeing, we used directional tests for measures of wellbeing (SWLS, ALOC, SPANE-P) and illbeing (SPANE-N, FHS, PSS, SSS, MHC-Soc, MHC-Emo, MHC-Psy). As we lacked specific a priori hypotheses about the way the PPIs would influence individualism and collectivism, we used non-directional tests of the fours ICS subscales. The p values for these were corrected for multiple tests using the Hommel (1988) method, a more powerful modification of a Bonferroni correction that is valid when hypotheses are independent or non-negatively associated (Sarkar, 1998; Sarkar & Chang, 1997). Whereas the Bonferroni method controls the family wise error rate (i.e., the proportion of expected false positives in all tests), the Hommel method controls the false discovery rate (the proportion of false positives among all positive tests). The Hommel method is preferable to Bonferroni because it is more powerful while still properly correcting for multiple tests. The Hommel procedure is stagewise, such that the most conservative corrections are applied to the largest p values. We also report the unadjusted p values for each test. More powerful modern procedures account for variability in p values using an informative covariate (Korthauer et al., 2019). In the absence of such a covariate, the Hommel method remains an appropriate choice.

6.2 Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analyses for the unadjusted tests with 87 participants indicated that the directional tests would have 80% power to detect effects at least as large as dz = 0.27, and the non-directional tests would have 80% power to detect effects at least as large as dz = 0.30. For the adjusted tests, we did not compute sensitivity, as the sensitivity for each test is dependent on the significance level of the other tests. Instead, we computed sensitivity using a Bonferroni adjusted significance level. Because the Hommel method is more powerful than a Bonferroni correction, this provides a lower limit of the sensitivity of the tests. With an adjusted significance level of 0.0036, 80% power is attained at dz = 0.39 for the directional tests and dz = 0.41 for the non-directional tests.

6.3 Paired t Tests

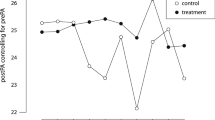

Analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021). Results are summarized in Table 2; Fig. 1. Prior to correcting for multiple tests, there was a significant increase in SWLS scores and significant decreases on the FHS, and PSS scales; however, these tests were non-significant after correcting for multiple tests. There were no significant changes on the other measures, which included the ALOC, SPANE-P, SPANE-N, SSS, the social, emotional, and psychological subscales of the MHC, and the four subscales of the ICS.

Standardized differences between T1 and T2 scores on indicators of wellbeing. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. SWLS = Satisfaction With Life Scale; ALOC = Academic Locus of Control; SPANE-P = positive affect subscale of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience; SPANE-N = negative affect subscale; FHS = Fear of Happiness Scale; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; SSS = Somatic Symptom Scale; MHC = Mental Health Checklist; Soc = social subscale; Emo = emotional subscale; Psy = psychological subscale; ICS = Individualism and Collectivism Scale; VC = Vertical Collectivism; HC = Horizontal Collectivism; VI = Vertical Individualism; HI = Horizontal Individualism

6.4 Assumptions of t Tests

Paired-samples t tests assume that the sampling distribution of the difference scores is normally distributed. To diagnose problems with this assumption, we computed skew and kurtosis values and conducted Shapiro–Wilk tests. These values are presented in Table 3. Shapiro–Wilk tests are known to be sensitive to small deviations from normality and as such, a significant test does not necessarily mean that a test is invalid. As such, we also produced quantile–quantile plots to visually inspect deviations from normality (see Fig. 2). Taken together, these results suggest non-normal sampling distributions of several study variables, most notably the ALOC, SPANE-N, and ICS-HI, all of which had substantial excess positive kurtosis. Excess positive kurtosis can be indicative of inflated effect size estimates which can cause type I errors. However, given that the tests using these variables were non-significant, and violations of assumptions rarely lead to type II errors, these violations do not alter our conclusions.

Quantile–quantile (q–q) plots of study variables. Theoretical quantiles under a normal distribution are plotted along the x-axis and observed scores are plotted along the y. An exactly normally distributed sample would correlate perfectly with the theoretical quantiles (represented by the line). Skewed distributions will appear curved, distributions with excess kurtosis will deviate from the theoretical quantiles at extreme values

A second assumption of paired t tests is that change scores are independent. This assumption was violated in our data. Participants belonged to one of four different classes, each with different instructors. Differences in class size and composition and instructors’ teaching styles make it likely that participants belonging to the same class would be more like one another than participants of different classes. We tested for differences between professors using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with professor as predictor and initial measurements as a control variable. Professor was not a significant predictor in any of these models. We also fit more complex linear mixed-effects models with professor as a random effect. Significance tests of the random effect of professor were all non-significant in these models. In short, although there was variability between professors, there was not sufficient evidence to conclude meaningful systematic differences.

7 Discussion

This study examines the effects of PPIs on students in the UAE taking a semester-long wellbeing and happiness course. Compared to pre-test, students were less fearful of happiness at post-test, suggesting that for some, literacy around wellbeing may have increased, a critical finding as mental health literacy is low in the region (Elyamani et al., 2021; Sweileh, 2021a). No significant changes for any other variables, i.e., perceived stress, satisfaction with life, locus of control, mental health status, somatic symptoms, negative affect, or cultural dimensions were observed, contrary to expectation and the prevailing literature (Basurrah et al., 2021, 2022; Bolier et al., 2013; Carr et al., 2020; Chakhssi et al., 2018; Hendriks et al., 2020; Hoppen & Morina, 2021; Koydemir et al., 2021; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009; van Agteren et al., 2021; White et al., 2019). While PPIs do work in the region, as recent meta-analyses (Bassurah et al., 2021, 2022) and independent studies (Lambert et al., 2019; Lambert, Passmore, Scull et al., 2019) confirm, it may be that for-credit classroom offerings do not yield the same returns as those found in clinical, online, community or laboratory settings. Alternatively, the population characteristics in this study, largely all Emirati nationals, may have contributed. Our study, alongside two other non-Western studies (i.e., Duan et al., 2021; Sarı Arasıl et al., 2020), are among the first to show that for-credit offerings did not yield wellbeing gains. We explore potential reasons for this.

Classroom-based skills approaches can lighten the financial, logistical and human resource load of building wellbeing and reduce the drop-out rates typical of community-based offerings (Lefevor et al., 2018; Young et al., 2020). Further, as cultural norms around ‘face-saving’ are central, that is, there is a preference to avoid public disclosure of issues that may negatively reflect upon one’s family or social group, a classroom-based skills approach may also be a good option to indirectly address issues of importance and decrease mental health stigma. Yet, this modality may be uniquely challenged by the need for assignments, exams, group projects, and grades, as well as influenced by student motives and instructor characteristics; hence, revising such courses to non-credit status may produce better wellbeing outcomes. Alternatively, revising expectations for the course’s wellbeing outcomes may also be warranted. Indeed, while Hobbs et al. (2022) showed positive but small effects, they also noted that for-credit offerings are low-intensity tools for large groups, but not high-intensity tools for individuals in clinical settings where efficacy is expectedly higher.

It may also be that such classes are not appropriate for local concerns. Developed in the West where mental health literacy and services are common, as well as cultural norms around the acceptability of discussing issues is standard, courses in other parts of the world may need to compensate for institutional, community and systemic gaps by expanding wellbeing to also address illbeing (Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020). If not managed within the family context, where issues are expected to be discussed, they may not be managed at all elsewhere and hence, the starting points for such courses may differ across geographic regions. The same can be said of community and institutional supports for issues students commonly face such as divorce, arranged marriage, addiction issues, pressure to have children, family abuse, and suicidal ideation (i.e., Baroud et al., 2019; Bromfield et al., 2016; Kostenko et al., 2016; van Buren & Van Gordon 2020; Wang & Kassam, 2016). PPIs may build wellbeing, but their utility may be limited towards issues for which they were not purposefully designed and in societies where the notion of wellbeing may differ altogether.

That our program did little else but reduce the fear of happiness is our biggest finding and is in line with the only prior UAE-based study showing the same (i.e., Lambert et al., 2019). However, that specific 16-week PPI program also produced significant wellbeing gains relative to a control group and over a three-month period, which this course did not. The only other difference being the cultural composition of the group (largely all Emirati nationals in the present study versus a diverse group of Muslim students from across the MENA region), as well as its modality (a PPI program within an introduction to psychology course that was framed as a bonus project versus a full for-credit course in itself). In both cases, education around happiness and wellbeing served to reduce the fear of happiness, but in the present study, did not serve to alter wellbeing outcomes. Students may have construed classroom content as an intellectual exercise for grades, but not as an invitation to internalize personal change. Collectivistic lifestyles that downgrade the expression of positive emotions and subordinate one’s personal happiness in favor of group harmony may also have contributed (Joshanloo, 2022; Joshanloo & Weijers, 2013).

There is yet another possibility. Many non-Western cultures do not perceive wellbeing and happiness with the same gusto, understanding, or perceived need for action. In the West, there is pressure to reduce negative emotional experiences, whereas in many Eastern cultures, distress is more easily tolerated and accepted. Distress may be construed as a spiritual test through which individuals are expected to travel (e.g., Eloul et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2020); hence, its presence is not psychologized, but spiritualized (Joshanloo et al., 2021). Considered a dialectical state, distress and happiness may more easily co-exist (Lomas, 2016), with resulting efforts to reduce illbeing, or increase wellbeing, not having the same urgency. Indeed, using data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of approximately 20,000 students in the UAE, Marquez et al. (2022) showed that of all demographic groups, Emirati nationals had the distinct profile of holding the highest scores for wellbeing (eudaimonic and hedonic measures) as well as concurrent high rates of mental health issues. Our study sample, also largely Emirati nationals, may not have benefited from this semester-long course for the same reason: there simply was no perceived need to change as both distress and wellbeing comfortably exist, and any intervention may have been considered unnecessary.

Finally, as with many happiness and wellbeing courses, ours was developed based on opportunity, rather than documented need. The popularity of such courses may drive similar decisions in institutions across the world; yet, examining what specific needs exist, if they are considered worthy of intervention and change, and only then, if PPIs are applicable, for whom, in what way, and why (Van Zyl et al., 2019) must first be considered. These questions likely differ by regional context (Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020; Sweileh, 2021a) and their determination is warranted in order to yield greater success and potentially explain why such interventions may not always meet their aims. For example, a study conducted in Turkey on a mandatory happiness and wellbeing university class (Sarı Arasıl et al., 2020) showed declines in social intelligence, increases in anxiety as well as avoidance attachment in relationships, and no gains in wellbeing despite participants self-reporting more happiness. A self-focus, endemic to PPIs and positive psychology, may create problems in non-Western collective societies, where excessive individual insight and personal evaluation of one’s motives, emotions, desires and goals may destabilize individuals, or at best, not produce the same desired outcomes. This reinforces the need for cultural integration in the regional use of PPIs. As happiness has a cultural component (Lambert D’raven & Pasha-Zaidi, 2014; Uchida & Ogihara 2012; Uchida & Oishi, 2016), the development of an Islamic positive psychology (Pasha-Zaidi, 2021), currently underway, may be a more effective solution.

8 Limitations and Future Directions

We did not measure adherence, which may have influenced practice effects; that is, whether students applied their learning beyond the classroom (Young et al., 2020). Further, comments suggested that some students registered for the course thinking it was an easy grade, others merely fulfilled elective requirements, and others were greatly enthused by the topic. Indeed, Hobbs et al. (2022) noted that students with little interest in wellbeing as a topic exhibited poorer wellbeing outcomes in their evaluated classes. Others were unfamiliar with experiential learning. These may have resulted in variable wellbeing scores for individual students, if not collectively (Young et al., 2020).

Our sample size was small and may be underpowered resulting in non-significant findings. Also, with academic samples, wellbeing generally drops near the end of term as exams approach and this could have obscured effects (i.e., Lambert et al., 2019; Young et al., 2020). There was no comparison group with which to establish baseline changes in indicators over time, a common limitation in studies (i.e., Sarı Arasıl et al., 2020), and which future research can address using a waitlist condition, or comparable psychology course. Future studies would also do well to monitor learning outcomes and include other variables, such as employment and health outcomes, as well as student engagement scores (Lambert et al., 2019; Young et al., 2020). Observing variables related to culture to ensure that PPIs do not undermine other strengths that build wellbeing is also advised (Lambert et al., 2019). We also agree with Van Zyl et al. (2019) that competency guidelines be developed and practice sessions maintained when implementing such courses. Investigating instructor characteristics in a bid to rule out confounding influences is also of interest, although our own study did not show differences by instructor.

9 Conclusion

As positive psychology makes its way around the world, we can potentially expect further studies like this to emerge as non-Western nations will have their own understandings of wellbeing and, far from being a negative, will serve to strengthen the field as it continues to evolve (Lambert et al., 2020; van Zyl & Rothmann 2022). Hence, findings like ours are not a dismissal of the need for wellbeing, but a call to culturalize and potentially even spiritualize its understanding (Joshanloo, 2021), rather than merely psychologize it. Indeed, the field of psychology itself, a Western construction, does not comfortably sit in all non-Western societies (Lambert et al., 2015). The lack of efficacy shown in our course is a paradoxical step forward, as it reinforces the need for more critical scientific investigation and more importantly, the development of an indigenous positive psychology (Lambert et al., 2015), that to date, has been stalled at copying popular and expensive Western notions of wellbeing. Hence, we call on all regional institutions to consider the effectiveness of their courses and challenge more critically what those results mean.

Higher education can do more to support the mental health and wellbeing of young people (Hood et al., 2021; Lambert, Abdulrehman et al., 2019; Yaden et al., 2021; Young et al., 2020), but how to do so effectively remains a question. Perhaps more consideration must be given to addressing local issues, rather than only topics promoted in the field. Still, a focus on the positive can allow all students to benefit without waiting to qualify with greater distress and serve to promote the wellbeing and mental health of young adults more broadly (Hobbs et al., 2022). All the same, while such courses generally cultivate wellbeing, our results and those of others show that they are not straightforward (Duan et al., 2021); defining their content (Hobbs et al., 2022), pedagogy and means of delivery (van Zyl et al., 2019) must be the next steps, with the results of such actions contributing to the pool of regional wellbeing data (e.g., Zeinoun et al., 2020), the effectiveness of PPIs as a whole, and greater insight into how best to apply them in educational settings around the world.

References

Ahuvia, A. C. (2002). Individualism/collectivism and cultures of happiness: A theoretical conjecture on the relationship between consumption, culture and subjective wellbeing at the national level. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015682121103

Aknin, L. B., & Dunn, E. W. (2013). Spending money on others leads to higher happiness than spending on yourself. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 93–98). APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-015

Alkhamees, A. A., Alrashed, S. A., Alzunaydi, A. A., Almohimeed, A. S., & Aljohani, M. S. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the general population of Saudi Arabia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152192

Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., & WHO WMH-ICS Collaborators. (2018). Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000362. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College

Baroud, E., Ghandour, L. A., Alrojolah, L., Zeinoun, P., & Maalouf, F. T. (2019). Suicidality among Lebanese adolescents: Prevalence, predictors and service utilization. Psychiatry Research, 275, 338–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.033

Basurrah, A. A., Di Blasi, Z., Lambert, L., Murphy, M., Warren, M. A., Setti, A., Al-Haj Baddar, M., & Shrestha, T. (2022). The effects of positive psychology interventions in Arab countries: A systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health & Wellbeing. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12391

Basurrah, A., Lambert, L., Setti, A., Murphy, M., Warren, M., Shrestha, T., & di Blasi, Z. (2021). Effects of positive psychology interventions in Arab countries: A protocol for a systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 11, e052477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052477

Boehm, J. K., Lyubomirsky, S., & Sheldon, K. M. (2011). A longitudinal experimental study comparing the effectiveness of happiness-enhancing strategies in Anglo Americans and Asian Americans. Cognition & Emotion, 25, 1263–1272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.541227

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Bmc Public Health, 13, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Bridges, K. R., Harnish, R. J., & Sillman, D. (2012). Teaching undergraduate positive psychology: An active learning approach using student blogs. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 11(2), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.2304/plat.2012.11.2.228

Bromfield, N. F., Ashour, S., & Rider, K. (2016). Divorce from arranged marriages: An exploration of lived experiences. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 57(4), 280–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2016.1160482

Brown, K., Ryan, R., & Creswell, J. (2007). Addressing fundamental questions about mindfulness. Psychological Inquiry, 18, 272–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701703344

Bryant, F., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Lawrence Erlbaum

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807

Chakhssi, F., Kraiss, J. T., Sommers-Spijkerman, M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2018). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmc Psychiatry, 18(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1739-2

Chan, M. F., Balushi, A., Al Falahi, R., Mahadevan, M., Al Saadoon, S., M., & Al-Adawi, S. (2021). Child and adolescent mental health disorders in the GCC: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 8(3), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpam.2021.04.002

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 386–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404

Colizzi, M., Lasalvia, A., & Ruggeri, M. (2020). Prevention and early intervention in youth mental health: Is it time for a multidisciplinary and trans-diagnostic model for care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14, 23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00356-9

Creswell, J. D., Welch, W. T., Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Gruenewald, T. L., & Mann, T. (2005). Affirmation of personal values buffers neuroendocrine and psychological stress responses. Psychological Science, 16, 846–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01624.x

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

Duan, S., Exter, M., Newby, T., & Fa, B. (2021). No impact? Long-term effects of applying the best possible self intervention in a real-world undergraduate classroom setting. International Journal of Community Wellbeing, 4, 581–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-021-00120-y

Eissa, A. M., Elhabiby, M. M., Serafi, E., Elrassas, D., Shorub, H. H., E. M., & El-Madani, A. A. (2020). Investigating stigma attitudes towards people with mental illness among residents and house officers: an Egyptian study. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 27(18), https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-020-0019-2

Eloul, L., Ambusaidi, A., & Al-Adawi, S. (2009). Silent epidemic of depression in women in the Middle East and North Africa Region: Emerging tribulation or fallacy? Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 9(1), 5–15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3074757/

Elyamani, R., Naja, S., Al-Dahshan, A., Hamoud, H., Bougmiza, M. I., & Alkubaisi, N. (2021). Mental health literacy in Arab states of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A systematic review. Plos One, 16(1), e0245156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245156

Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377

Fischer, P., Sauer, A., Vogrincic, C., & Weisweiler, S. (2010). The ancestor effect: Thinking about our genetic origin enhances intellectual performance. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.778

Fischer, R., Bortolini, T., Karl, J. A., Zilberberg, M., Robinson, K., Rabelo, A., & Mattos, P. (2020). Rapid review and meta-meta-analysis of self-guided interventions to address anxiety, depression, and stress during COVID-19 social distancing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.563876

Foody, M., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). On making people more positive and rational: The potential downsides of positive psychology interventions. In T. B. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 166–193). New Harbinger

Gable, S. L. (2013). Capitalizing on positive events. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 71–76). APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-012

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Wyss, T. (2013). Strength-based positive interventions: Further evidence for their potential in enhancing well-being and alleviating depression. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1241–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9380-0

GBD 2015 Eastern Mediterranean Region Mental Health Collaborators. (2018). The burden of mental disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2015: Findings from the global burden of disease 2015 study. International Journal of Public Health, 63(Suppl 1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-017-1006-1

Gierk, B., Kohlmann, S., Kroenke, K., Spangenberg, L., Zenger, M., Brähler, E., & Löwe, B. (2014). The Somatic Symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8): A brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179

Goodmon, L. B., Middleditch, A. M., Childs, B., & Pietrasiuk, S. E. (2016). Positive psychology course and its relationship to well-being, depression, and stress. Teaching of Psychology, 43(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628316649482

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2018). The efficacy of positive psychology interventions from non-Western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.711

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Jong, J., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 357–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1

Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2018). How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941

Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of university students: A bibliometric map** of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226

Hobbs, C., Jelbert, S., Santos, L. R., & Hood, B. (2022). Evaluation of a credit-bearing online administered happiness course on undergraduates’ mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos One, 17(2), e0263514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263514

Hommel, G. (1988). A stagewise rejective multiple test procedure based on a modified Bonferroni test. Biometrika, 75(2), 383–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/75.2.383

Hood, B., Jelbert, S., & Santos, L. R. (2021). Benefits of a psychoeducational happiness course on university student mental well-being both before and during a COVID-19 lockdown. Health Psychology Open, 8(1), 2055102921999291. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102921999291

Hoppen, T. H., & Morina, N. (2021). Efficacy of positive psychotherapy in reducing negative and enhancing positive psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal Open, 11(9), e046017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046017

Huang, L., Kern, M. L., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Strengthening university student wellbeing: Language and perceptions of Chinese international students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155538

Joshanloo, M. (2022). Predictors of aversion to happiness: New insights from a multi-national study. Motivation and Emotion. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09954-1

Joshanloo, M., Lepshokova, Z. K., Panyusheva, T., Natalia, A., Poon, W. C., Yeung, V. W. L., & Tsukamoto, S. (2014). Cross-cultural validation of fear of happiness scale across 14 national groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45, 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113505357

Joshanloo, M., Van de Vliert, E., & Jose, P. E. (2021). Four fundamental distinctions in conceptions of wellbeing across cultures. In M. L. Kern, & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64537-3_26

Joshanloo, M., & Weijers, D. (2013). Aversion to happiness across cultures: A review of where and why people are averse to happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9489-9

Joshanloo, M., Weijers, D., Jiang, D. Y., Han, G., Bae, J., Pang, J. S., & Natalia, A. (2015). Fragility of happiness beliefs across 15 national groups. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(5), 1185–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9553-0

Joshanloo, M., Wissing, M. P., Khumalo, T., & Lamers, S. M. A. (2013). Measurement invariance of the Mental Health Continuum-Short form (MHC-SF) across three cultural groups. Personality and Individual Difference, 55, 755–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.002

Keyes, C. L. M. (2009). Atlanta: Brief description of the Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF).http://www.sociology.emory.edu/ckeyes/

Kim, H., Doiron, K., Warren, M. A., & Donaldson, S. I. (2018). The international landscape of positive psychology research: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651

Kim-Prieto, C., & D’Oriano, C. (2011). Integrating research training and the teaching of positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 457–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.634827

Kleinman, K. E., Asselin, C., & Henriques, G. (2014). Positive consequences: The impact of an undergraduate course on positive psychology. Psychology, 5, 2033–2045. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.518206

Korthauer, K., Kimes, P. K., Duvallet, C., Reyes, A., Subramanian, A., Teng, M., Shukla, C., Alm, E., & Hicks, S. C. (2019). A practical guide to methods controlling false discoveries in computational biology. Genome Biology, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1716-1

Kostenko, V. V., Kuzmuchev, P. A., & Ponarin, E. D. (2016). Attitudes towards gender equality and perception of democracy in the Arab world. Democratization, 23(5), 862–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1039994

Koydemir, S., Sökmez, A. B., & Schütz, A. (2021). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of randomized controlled positive psychological interventions on subjective and psychological well-being. Applied Research Quality Life, 16, 1145–1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-019-09788-z

Lambert, L. (2012). Happiness 101: A how-to guide in positive psychology for people who are depressed, languishing, or flourishing (The facilitator guide). Xlibris Corporation

Lambert, L., Abdulrehman, R., & Mirza, C. (2019). Coming full circle: Taking positive psychology to GCC universities. In L. Lambert & N. Pasha-Zaidi (Eds.), Positive Psychology in the Middle East/North Africa: Research, Policy, and Practise (pp. 93–110). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13921-6_5

Lambert, L., Draper, Z. A., Warren, M. A., Joshanloo, M., Chiao, E. L., Schwam, A., & Arora, T. (2021). Conceptions of happiness matter: Relationships between fear and fragility of happiness and mental and physical wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00413-1

Lambert, L., Lomas, T., van de Weijer, M. P., Passmore, H. A., Joshanloo, M., Harter, J., Ishikawa, Y., Lai, A., Kitagawa, T., Chen, D., Kawakami, T., Miyata, H., & Diener, E. (2020). Towards a greater global understanding of wellbeing: A proposal for a more inclusive measure. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(2), 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i2.1037

Lambert, L., Pasha-Zaidi, N., Passmore, H. A., & Al-Karam, Y., C (2015). Develo** an indigenous positive psychology in the United Arab Emirates. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 1–23

Lambert, L., Passmore, H. A., & Joshanloo, M. (2019). A positive psychology intervention program in a culturally-diverse university: Boosting happiness and reducing fear. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1141–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z

Lambert, L., Passmore, H. A., Scull, N., Sabah, A., I., & Hussain, R. (2019). Wellbeing matters in Kuwait: The Alnowair’s Bareec education initiative. Social Indicators Research, 143(2), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1987-z

Lambert, L., Warren, M. A., Schwam, A., & Warren, M. T. (2021). Positive psychology interventions in the United Arab Emirates: Boosting wellbeing – and changing culture? Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02080-0

Lambert, D., L., & Pasha-Zaidi, N. (2014). Happiness strategies among Arab university students in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Happiness and Well-Being, 2(1), 131–144

Lamers, S. M. A., Glas, C. A. W., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2012). Longitudinal evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000109

Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034709

Lee, E. H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004

Lefevor, G. T., Jensen, D. R., Jones, P. J., Janis, R. A., & Hsieh, C. H. (2018, December 5). An undergraduate positive psychology course as prevention and outreach. Preprint, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/r52wg

Lomas, T. (2016). Flourishing as a dialectical balance: Emerging insights from second wave positive psychology. Palgrave Communications, 2, 16018

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

Lyubomirsky, S., & Layous, K. (2013). How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412469809

Maalouf, F. T., Alamiri, B., Atweh, S., Becker, A. E., Cheour, M., Darwish, H., & Akl, E. A. (2019). Mental health research in the Arab region: Challenges and call for action. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(11), 961–966. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30124-5

Macaskill, A. (2013). The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41, 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.743110

Marquez, J., Lambert, L., & Cutts, M. (2022). ; in preparation). Geographic, socio-demographic and school type variation in adolescent wellbeing and mental health in the United Arab Emirates

Morgan, B., & Simmons, L. (2021). A ‘PERMA’ response to the pandemic: An online positive education programme to promote wellbeing in university students. Frontiers in Education, 18, https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.642632

Pasha-Zaidi, N. (Ed.). (2021). Toward a positive psychology of Islam and Muslims: Spirituality, struggle, and social justice. Springer. https://springer.longhoe.net/book/10.1007/978-3-030-72606-5

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rao, M. A., Donaldson, S. I., & Doiron, K. M. (2015). Positive psychology research in the Middle East and North Africa. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 60–76. https://middleeastjournalofpositivepsychology.org/index.php/mejpp/article/view/33

Rashid, T., & Al-Haj Baddar, M. K. (2019). Positive psychotherapy: Clinical and cross-cultural applications of positive psychology. In L. Lambert & N. Pasha-Zaidi (Eds.), Positive psychology in the Middle East/North Africa: Research, policy, and practise (pp. 333–362). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13921-6_15

Russo-Netzer, P., & Ben-Shahar, T. (2011). ‘Learning from success’: A close look at a popular positive psychology course. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 468–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.634823

Sarkar, S. (1998). Some probability inequalities for ordered MTP2 random variables: a proof of Simes conjecture. Annals of Statistics, 26, 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1028144846

Sarkar, S., & Chang, C. K. (1997). The Simes method for multiple hypothesis testing with positively dependent test statistics. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92, 1601–1608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2965431

Sarı Arasıl, A. B., Turan, F., Metin, B., Sinirlioğlu Ertaş, H., & Tarhan, N. (2020). Positive psychology course: A way to improve well-being. Journal of Education and Future, 17, 15–23. https://doi.org/10.30786/jef.591777

Sheldon, K. M., Abad, N., Ferguson, Y., Gunz, A., Houser-Marko, L., Nichols, C. P., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2010). Persistent pursuit of need-satisfying goals leads to increased happiness: A 6-month experimental longitudinal study. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-009-9153-1

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing. Free Press

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410

Shin, L. J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2016). Positive activity interventions for mental health conditions: Basic research and clinical applications. In J. Johnson & A. Wood (Eds.), The handbook of positive clinical psychology (pp. 349–363). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118468197.ch23

Sin, N., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., de Salazar, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2021). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Sweileh, W. M. (2021a). Global research activity on mental health literacy. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 28, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00125-5

Sweileh, W. M. (2021b). Contribution of researchers in the Arab region to peer-reviewed literature on mental health and well-being of university students. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00477-9

Thomas, M. D., & McPherson, B. J. (2011). Teaching positive psychology using team-based learning. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(6), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.634826

Triandis, H. C., & Gelfland, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118

Trice, A. (1985). An academic locus of control scale for college students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 61, 1043–1046. http://apexed.webstarts.com/uploads/TriceAcademicLocusofControlScaleKeyandExplanation.pdf

Trice, A. D., Ogden, E. P., Stevens, W., & Booth, J. (1987). Concurrent validity of the academic locus of control scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 47, 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164487472022

Uchida, Y., & Ogihara, Y. (2012). Personal or interpersonal construal of happiness: A cultural psychological perspective. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(4), 354–369. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.5

Uchida, Y., & Oishi, S. (2016). The happiness of individuals and the collective. Japanese Psychological Research, 58, 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12103

van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(5), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w

Van Buren, F., & Van Gordon, W. (2020). Emirati women’s experiences of consanguineous marriage: A qualitative exploration of attitudes, health challenges, and co** styles. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 1113–1127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00123-z

Van Zyl, L. E., Efendic, E., Rothmann, R. S., & Shankland, R. (2019). Best-practice guidelines for positive psychological intervention research design. In L. E. Van Zyl & S. Rothmann Sr. (Eds.), Positive psychological intervention design and protocols for multi-cultural contexts (pp. 1–32). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20020-6_1

Van Zyl, L. E., & Rothmann, S. (2022). Grand challenges for positive psychology: Future perspectives and opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 833057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833057

Wang, Y., & Kassam, M. (2016). Indicators of social change in the UAE: College students’ attitudes toward love, marriage and family. Journal of Arabian Studies, 6(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2016.1192791

Waters, L., Algoe, S. B., Dutton, J., Emmons, R., Fredrickson, B. L., Heaphy, E., & Steger, M. (2021). Positive psychology in a pandemic: Buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1871945

Watkins, P. C., Sparrow, A., & Webber, A. C. (2013). Taking care of business with gratitude. In J. F. Froh & A. C. Parks (Eds.), Activities for teaching positive psychology: A guide for instructors (pp. 119–128). APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/14042-019

White, C. A., Uttl, B., & Holder, M. D. (2019). Meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions: The effects are much smaller than previously reported. Plos One, 14(5), e0216588. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216588

Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2017). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Positive Psychology (pp. 142–160). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315659794-12

Wood, A. M., & Joseph, S. (2010). The absence of positive psychological (eudemonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: A ten-year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 213–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032

Yaden, D. B., Claydon, J., Bathgate, M., Platt, B., & Santos, L. R. (2021). Teaching well-being at scale: An intervention study. Plos One, 16(4), e0249193. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249193

Young, T., Macinnes, S., Jarden, A., & Colla, R. (2020). The impact of a wellbeing program imbedded in university classes: The importance of valuing happiness, baseline wellbeing and practice frequency. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1793932

Zeinoun, P., Akl, E. A., Maalouf, F. T., & Meho, L. I. (2020). The Arab region’s contribution to global mental health research (2009–2018): A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00182

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Emirates Center for Happiness Research at the United Arab Emirates University for this grant and collegial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statements and Declarations

This research received a grant from the Emirates Center for Happiness Research (United Arab Emirates University).

Conflict of Interest

The first author was also the course developer and a previous faculty member with the United Arab Emirates University. None of the other co-authors were involved in the project, other than to analyse the data independently.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lambert, L., Draper, Z.A., Warren, M.A. et al. Assessing a Happiness and Wellbeing Course in the United Arab Emirates: It is What They Want, but is it What They Need?. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 8, 115–137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-022-00080-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-022-00080-4