Abstract

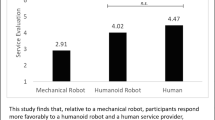

An increasing number of firms introduce service robots, such as physical robots and virtual chatbots, to provide services to customers. While some firms use robots that resemble human beings by looking and acting humanlike to increase customers’ use intention of this technology, others employ machinelike robots to avoid uncanny valley effects, assuming that very humanlike robots may induce feelings of eeriness. There is no consensus in the service literature regarding whether customers’ anthropomorphism of robots facilitates or constrains their use intention. The present meta-analysis synthesizes data from 11,053 individuals interacting with service robots reported in 108 independent samples. The study synthesizes previous research to clarify this issue and enhance understanding of the construct. We develop a comprehensive model to investigate relationships between anthropomorphism and its antecedents and consequences. Customer traits and predispositions (e.g., computer anxiety), sociodemographics (e.g., gender), and robot design features (e.g., physical, nonphysical) are identified as triggers of anthropomorphism. Robot characteristics (e.g., intelligence) and functional characteristics (e.g., usefulness) are identified as important mediators, although relational characteristics (e.g., rapport) receive less support as mediators. The findings clarify contextual circumstances in which anthropomorphism impacts customer intention to use a robot. The moderator analysis indicates that the impact depends on robot type (i.e., robot gender) and service type (i.e., possession-processing service, mental stimulus-processing service). Based on these findings, we develop a comprehensive agenda for future research on service robots in marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Technology is vital for expansion of the service economy (Huang and Rust 2017). Service robots are expected to change the way services are provided and to alter how customers and firms interact (van Doorn et al. 2017). Service robots are defined as autonomous agents whose core purpose is to provide services to customers by performing physical and nonphysical tasks (Joerling et al. 2019). They can be physically embodied or virtual (for example, voice- or text-based chatbots). The market value for service robots is forecast to reach US$ 699.18 million by 2023 (Knowledge Sourcing Intelligence 2018). SoftBank has sold more than 10,000 of its humanoid service robot, Pepper, since launching it in 2014 (Mende et al. 2019). Pepper is employed by service providers in restaurants, airports, and cruise liners to greet guests and help them navigate the location. It is highly likely that robots will become more common and that customers will have to use them more in the future.

The present study enhances understanding of how customers interact with and experience inanimate objects such as service robots. Marketing has long studied various customer–object relations. For example, studies have taken a sensual perception or affective relational perspective. As customers’ initial responses to objects are often driven by the objects’ sensual appeal, sensory marketing has explored how customers perceive objects through different inputs of their five senses (Bosmans 2006; Peck and Childers 2006). Additionally, scholars have explored emotional customer–object relations. These affective relations mainly occur in contexts regarding consumption objects and possessions, where product attachment and material possession love impact consumption behavior (Kleine and Baker 2004; Lastovicka and Sirianni 2011). Another literature stream examines how customers anthropomorphize objects, such as service robots, and assign human characteristics to them (Epley et al. 2007).

To facilitate customer–robot interactions, marketing managers often favor humanlike service robots to increase customers’ perceptions of social presence (Niemelä et al. 2017). These robots have a human shape, show human characteristics, or imitate human behavior (Bartneck et al. 2009). In the virtual context, chatbots’ mimicry of human behavior can often convince customers that they have been interacting with a human (Wünderlich and Paluch 2017). Novak and Hoffman (2019) note a growing consensus in marketing and psychology that anthropomorphism is important for understanding how customers experience inanimate objects (MacInnis and Folkes 2017; Waytz et al. 2014). Anthropomorphism in this study refers to the extent to which customers perceive service robots as humanlike, rather than to the extent to which firms design robots as humanlike. According to Epley et al. (2007, p. 865), this perception results from “the attribution of human characteristics or traits to nonhuman agents.”

While marketing has found anthropomorphism to increase product and brand liking (Aggarwal and Gill 2012), whether anthropomorphism in service robots enhances customers’ experiences is unclear. Some scholars argue that perception of humanlike qualities in service robots facilitates engagement with customers, since it “incorporates the underlying principles and expectations people use in social settings in order to fine-tune the social robot’s interaction with humans” (Duffy 2003, p. 181). However, others are more skeptical; as perceived anthropomorphism increases, “consumers will experience discomfort – specifically, feelings of eeriness and a threat to their human identity” (Mende et al. 2019, p. 539). Although scholars have frequently examined the impact of anthropomorphism on customer intention to use a service robot, results are inconsistent, showing positive (Stroessner and Benitez 2019), neutral (Goudey and Bonnin 2016), and negative (Broadbent et al. 2011) effects. Thus, clear management guidelines are lacking, which is unfortunate given firms’ need to “carefully consider how to use AI [artificial intelligence] to engage customers in a more systematic and strategic way” (Huang and Rust 2020, p. 3).

In response to calls by Thomaz et al. (2020) and van Doorn et al. (2017) for more research on when and why customers anthropomorphize service robots and how anthropomorphism influences customer outcomes, the present study uses meta-analysis to enhance understanding of the role of anthropomorphism in influencing customer use intention of service robots. The meta-analysis develops and tests a comprehensive framework to clarify the effects of anthropomorphism on important customer outcomes, assess mediators, identify factors that affect customers’ propensity to anthropomorphize robots, and analyze how contextual factors affect anthropomorphism (Grewal et al. 2018). We thus make several contributions.

First, we synthesize previous research on the relationship between robot anthropomorphism and customer use intention. While one literature stream refers to anthropomorphism theory and suggests that anthropomorphism has positive effects on technology use (Duffy 2003), other literature streams refer either to uncanny valley theory or expectation confirmation theory and argue in favor of negative effects (Ho and MacDorman 2010). Our meta-analysis resolves these inconsistent findings, clarifying whether and under what circumstances customers appreciate anthropomorphism, and whether this relates positively or negatively to technology perception and use intention. The results will guide managers in whether to consider anthropomorphism as a factor influencing robot use.

Second, we examine the mediating mechanisms between service robot anthropomorphism and customer use intention. Considering mediators is vital because it helps scholars avoid overestimating or underestimating the importance of anthropomorphism (Iyer et al. 2011; Qiu and Benbasat 2009), thus supporting a positive effect of anthropomorphism on intention to use. However, this is not always the case. Goudey and Bonnin (2016) found that the anthropomorphism of a companion robot did not increase use intention thereof, and some studies have found that people prefer a less humanlike robot (Broadbent et al. 2011) or an explicitly machinelike robot (Vlachos et al. 2016), suggesting a negative effect of anthropomorphism. This seems to support Mori’s (1970) uncanny valley hypothesis that the use intention of a robot does not always increase with its humanlikeness; people may find a highly humanlike robot creepy and uncanny, and feelings of eeriness or discomfort may lead to rejection. In addition, Goetz et al. (2003) found that although people prefer humanlike robots for social roles, they prefer machinelike robots for more investigative roles, such as lab assistant. These mixed findings indicate the complexity of the relationship between anthropomorphism and use intention, and suggest that the effects of robot anthropomorphism on customer use intention are multi-faceted and contingent. To address this complexity and offer a fuller understanding of this important relationship, we included relevant mediators and moderators in our meta-analysis.

Antecedents of anthropomorphism

We considered two sets of antecedents: customer characteristics and robot design features, since anthropomorphism is not merely the result of a process triggered by an agent’s humanlike features but also reflects customer differences in anthropomorphizing tendencies (Waytz et al. 2014). To select relevant customer characteristics as antecedent variables, we focused on five customer traits and predispositions that have been shown to impact customer use of new technologies: competence, prior experience, computer anxiety, need for interaction, and negative attitudes toward robots (NARS), all of which are technology-related psychological factors. The first four variables come from Epley et al.’s (2007) theory of anthropomorphism, and the last variable is a robot-related general attitude frequently used in HRI research. We also included sociodemographic variables as antecedents. Finally, we included major physical and nonphysical robot design features as antecedents of anthropomorphism.

Traits and predispositions

Competence

Competence can be defined as the customer’s potential to use a service robot to complete a task or performance successfully. It is a multi-faceted construct composed of an individual’s knowledge of and ability to use a robot. It relates to individual factors such as knowledge, expertise, and self-efficacy (Munro et al. 1997). According to Epley et al. (2007), the first of the three psychological determinants of anthropomorphism is elicited agent knowledge; for customers who are knowledgeable about robots, anthropomorphic knowledge and representation are readily accessible and applicable, and therefore they are more likely to humanize the robot. The literature provides limited empirical evidence for a positive effect of competence on anthropomorphism, suggesting that after interacting with or using a robot, people tend to anthropomorphize it more (Fussell et al. 2008). Other studies, however, have found no influence (Ruijten and Cuijpers 2017) or even a negative relationship (Haring et al. 2015). It seems that the more people are capable of using a robot, the lower their anthropomorphic tendency, because there is no need to facilitate the interaction by humanizing the robot.

Prior experience

Prior experience comprises the individual’s opportunity to use a specific technology (Venkatesh et al. 2012). In contrast to competence, robot-related experience implies previous initial contact or interaction with a service robot that does not necessarily include fulfilling a task (MacDorman et al. 2009). The influence of robot-related experience on anthropomorphism is unclear, with contradictory findings. Some studies provide evidence of a positive effect on anthropomorphism (Aroyo et al. 2017), in line with Epley et al. (2007). The elicited agent knowledge in the form of robot-related experience could result in the projection of human attributes to the service robot (Epley et al. 2007). However, several studies indicate a negative effect of experience on anthropomorphism (Haring et al. 2016), or a nonsignificant effect (Stafford 2014).

Computer anxiety

Computer anxiety is the degree of an individual’s apprehension, or even fear, regarding using computers (Venkatesh 2000). Robots are essentially a computer-based technology, and people with different anxiety levels may react differently to robots. According to Epley et al. (2007), the second determinant of anthropomorphism is effectance, the motivation to explain and understand nonhuman agents’ behavior. People high in computer anxiety are more likely to feel a lack of control and uncertain about interacting with a robot, and so their effectance motivation is typically stronger; that is, they have a higher desire to reduce uncertainty by controlling the robot. Anthropomorphism can satisfy this need by increasing someone’s ability to make sense of a robot’s behavior and their confidence in controlling the robot during the interaction (Epley et al. 2008). Thus, anxiety associated with uncertainty should increase the tendency to humanize a robot.

Need for interaction

Like the need to belong and the need for affiliation, the need for interaction is a desire to retain personal contact with others (particularly frontline service employees) during a service encounter (Dabholkar 1996). This relates to the third psychological determinant of anthropomorphism, sociality, which is the need and desire to establish social connections with other humans (Epley et al. 2007). Research indicates that lonely people have a stronger tendency to humanize robots, perhaps because of social isolation, exclusion, or disconnection (Kim et al. 2013). Anthropomorphism can satisfy their need to belong and desire for affiliation by enabling a perceived humanlike connection with robots. Similarly, in a robot service context where social connection with frontline service employees is lacking, customers with a greater need for interaction may compensate and attempt to alleviate this social pain by perceiving a service robot as more humanlike, thus creating a humanlike social interaction (Epley et al. 2008). Therefore, need for interaction should increase customers’ tendency to humanize a service robot.

Negative attitudes toward robots in daily life (NARS)

The concept of NARS (Nomura et al. 2006) captures a general attitude and predisposition toward robots, and is a key psychological factor preventing humans from interacting with robots. While both anthropomorphism and NARS are important constructs in HRI research, their relationship remains understudied and unclear (Destephe et al. 2015). We suggest that NARS may influence anthropomorphism in a similar way to computer anxiety, because both are negative predispositions toward technology (Broadbent et al. 2009). A distinction is important, as computer anxiety is broader (referring to computer technology in general) and emotional (involving fear), whereas NARS is more specific (robot-focused) and attitudinal (involving dislike); nevertheless, the former may lead to the latter (Nomura et al. 2006). Customers with high NARS will feel uncomfortable when interacting with a robot in a service encounter because in general they do not like robots. Hence, in order to facilitate the interaction and improve the service experience, they will tend to anthropomorphize the robot and treat it like a human service employee. We predict a positive influence of NARS on anthropomorphism.

Sociodemographics

Age

In general, age is found to negatively impact people’s willingness to use robots (Broadbent et al. 2009); older people are more skeptical about technology, have more negative attitudes toward robots, and therefore have lower intention to use them. However, a study on healthcare robots found no age effects, suggesting that age need not be a barrier (Kuo et al. 2009). Regarding age influences on anthropomorphism, the literature has focused on children and elderly people, and findings suggest that these segments have a strong tendency to humanize robots (Sharkey and Sharkey 2011). For example, there is evidence that children anthropomorphize nonhuman agents more than adults do (Epley et al. 2007); they tend to ascribe human attributes such as free will, preferences, and emotions even to simple robots, although this tendency decreases with age. There are also indications that people are more likely to anthropomorphize robots as their age increases (Kamide et al. 2013).

Customer gender

Research shows that in general men hold more favorable attitudes toward robotic technologies, tend to perceive robots as more useful, and are more willing to use robots in their daily lives; women are more skeptical about interacting with robots, tend to evaluate them more negatively, and are less likely to use them (de Graaf and Allouch 2013). Therefore, most studies have found that women anthropomorphize robots more strongly than men do (Kamide et al. 2013), perhaps because of high effectance and sociality motivations resulting from technology anxiety or a need for social connection (Epley et al. 2007). Nevertheless, some studies have argued that men tend to perceive a robot as an autonomous person and therefore anthropomorphize robots more compared to women (de Graaf and Allouch 2013). Others have found no gender differences (Athanasiou et al. 2017).

Education

There is a lack of clarity about the effects of an individual’s educational level on their perceptions and evaluations of robots (Broadbent et al. 2009). Evidence that higher education is associated with more positive attitudes toward robots is limited (Gnambs and Appel 2019). Research has yet to examine explicitly whether and how anthropomorphic tendencies vary with educational level. However, anthropomorphism theory suggests that people of modern cultures are more familiar with and knowledgeable about technological devices than those of nonindustrialized cultures (Epley et al. 2007). Since they have greater understanding of how these technological devices work and how to use them, they are less likely to anthropomorphize them. This argument suggests a negative effect of education on anthropomorphism, because people of modern cultures are generally better educated than those of nonindustrialized cultures.

Income

Income is the least examined sociodemographic factor in HRI research. Gnambs and Appel (2019) found that white-collar workers held slightly more favorable attitudes toward robots than blue-collar workers. While there is no direct empirical evidence for the effect of income on anthropomorphism, we suggest that it may be similar to the effect of education, because education and income are highly related and are both indicators of social class. People with higher incomes have more opportunities to interact with innovative technologies such as service robots at work and in their daily lives. They are more capable of using robots, and therefore more likely to acquire nonanthropomorphic representations of robots’ inner workings and less likely to humanize them (Epley et al. 2007).

Robot design

Physical features

It is relatively intuitive that a robot’s physical appearance or embodiment can affect the extent to which it is anthropomorphized. Research has consistently shown that the presence of human features such as head, face, and body increases the perceived humanlikeness of a robot (Erebak and Turgut 2019; Zhang et al. 2010). These physical features serve as observable cues of humanlikeness; hence, the more human features a robot possesses, the more strongly it is anthropomorphized.

Nonphysical features

Nonphysical features mainly refer to robots’ behavioral characteristics, such as gaze, gesture, voice, and mimicry. Research shows that robots with the abilities to make eye contact, use gestures, move, and talk when interacting with people are perceived as more humanlike than those without such abilities, and that the more a robot gazes, gestures, moves, and talks like a human, the more anthropomorphic it is perceived (Kompatsiari et al. 2019; Salem et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2010). However, this positive effect of behavioral features on anthropomorphism is sometimes found nonsignificant (Ham et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2019). Nonphysical features also include a robot’s emotionality and personality, which also influence people’s anthropomorphic perceptions. For example, Novikova (2016) reported that an emotionally expressive robot was rated significantly higher on anthropomorphism versus a nonemotional robot. Moshkina (2011) found that an extraverted robot was rated as more humanlike than an introverted one.

Mediators of anthropomorphism

To provide a full account of the multi-faceted effects of robot anthropomorphism on customer use intention, we examined three sets of mediators from the literature. First, from HRI research we drew four major robot characteristics as robot-related mediators (Bartneck et al. 2009); to capture the social aspect of a service robot, we also included social presence as a fifth robot characteristic (van Doorn et al. 2017). Second, from technology acceptance research we included usefulness and ease of use as functional mediators (Davis et al. 1989). Robots are essentially a form of technology, and these two variables appear to play key mediating roles in technology acceptance (Blut et al. 2016; Blut and Wang 2020). Third, drawing on the relationship marketing literature, we incorporated five common relational mediators; unlike other forms of technology, relationship-building with robots, especially service robots, is possible and even desired by customers. Thus, we extended Wirtz et al.’s (2018) robot acceptance model by systematically examining robot-related, functional, and relational factors as mediators in the anthropomorphism–use intention relationship. We now discuss the effect of anthropomorphism on each mediator. We will not discuss the effects of mediators on use intention, because they are well-established in the relevant literature on HRI, technology acceptance, and marketing.

Robot-related mediators

Animacy

Animacy is the extent to which a robot is perceived as being alive (Bartneck et al. 2009). Robots high in animacy are lifelike creatures that seem capable of connecting emotionally with customers and triggering emotions. Research often reports a highly positive correlation between anthropomorphism and animacy, suggesting conceptual overlap (Ho and MacDorman 2010) as being alive is an essential part of being humanlike (Bartneck et al. 2009). For example, Castro-González et al. (2018) found that the more humanlike a robot’s mouth is perceived by people, the more alive the robot is rated. Thus, anthropomorphism should positively impact animacy; the more a robot is humanized, the more lifelike the perception. In service contexts, this means that when customers perceive a service robot as more humanlike, they are more likely to feel as if they are interacting with a human service employee rather than a machine.

Intelligence

Intelligence is the extent to which a robot appears to be able to learn, reason, and solve problems (Bartneck et al. 2009). There is evidence that anthropomorphism increases customers’ perceptions of the intelligence of various smart technologies, including robots. Canning et al. (2014) showed that customers perceived humanlike robots as more intelligent than machinelike ones. When people anthropomorphize a robot, they typically treat it as a human being and expect it to exhibit aspects of human intelligence (Huang and Rust 2018). The more humanlike the robot is perceived, the more human intelligence people tend to ascribe to it. In service contexts, this suggests that when customers humanize a service robot, they tend to have higher expectations of its ability to deliver a service.

Likability

Likability is the extent to which a robot gives positive first impressions (Bartneck et al. 2009). Attractiveness is a similar concept, and anthropomorphism can help to make a robot aesthetically appealing and socially attractive. Numerous studies have confirmed a positive effect of anthropomorphism on likeability (Castro-González et al. 2018; Stroessner and Benitez 2019). When people humanize a robot, it becomes more similar to them, which leads to a good first impression (van Doorn et al. 2017). Therefore, the greater the tendency to anthropomorphize a robot, the more people like the robot. In a service context, the positive effect of anthropomorphism on likability means that the humanlikeness of a service robot will enhance first impressions of the robot as a service provider. However, in line with uncanny valley theory (Mori 1970), some studies have found that a robot’s likability does not always increase with anthropomorphism; if it feels uncannily human, people find it unlikable (Mende et al. 2019).

Safety

Safety is the customer’s perception of the level of danger involved in interacting with a robot (Bartneck et al., 2009). It relates to feelings of risk and invasion of privacy. Bartneck et al. (2009) suggested that for someone to use a robot as a partner and coworker, it is necessary to achieve a positive perception of safety. This is especially true for service robots, because customer–robot interaction and co-production are inevitable. According to Epley et al. (2007), anthropomorphism can facilitate perceptions of safety by increasing the sense of the predictability and controllability of the nonhuman agent during interactions, thereby reducing feelings of risk and danger. For example, Benlian et al. (2019) showed that feelings of privacy invasion when using smart home assistants are lower when the technology is anthropomorphized by users. Thus, the literature supports a positive effect of anthropomorphism on perceived safety. In a service context, this suggests that the more a customer perceives a service robot as humanlike, the safer the service experience appears.

Social presence

Social presence is the extent to which a human believes that someone is really present (Heerink et al. 2008). In HRI, social presence is “the extent to which machines (e.g., robots) make consumers feel that they are in the company of another social entity” (van Doorn et al. 2017, p. 44). This robot characteristic can satisfy sociality needs (Epley et al. 2007) and is therefore important for those with a greater need for interaction. The relationship between anthropomorphism and social presence is intuitive and straightforward. By making humans out of robots, people feel that they are interacting with and connecting to another person. Therefore, anthropomorphism evokes a sense of social presence, and literature widely supports this positive effect (Kim et al. 2013). Thus, in a service context, robots that are perceived as more humanlike can provide customers with a stronger social presence, thereby enriching social interaction.

Functional mediators

Ease of use

As a key determinant in the technology acceptance model (TAM), ease of use is the degree to which a customer finds using a technology to be effortless (Davis et al. 1989). With few exceptions (Wirtz et al. 2018), ease of use has not been examined in robot studies. However, research suggests that anthropomorphism makes a robot more humanlike and thus more familiar. Familiarity can help people learn how to use a robot and interact with it more easily, and humanlikeness makes this interaction more natural (Erebak and Turgut 2019); this will increase the perceived ease of use. Hence, a positive effect of anthropomorphism on ease of use is expected. In a service context, this means that customers tend to see a humanlike service robot as easier to work with than a machinelike one. However, empirical analysis is lacking, barring one study that did not support this effect (Goudey and Bonnin 2016).

Usefulness

Defined as the subjective probability that using a technology will improve the way a customer completes a given task (Davis et al. 1989), usefulness is another key determinant in TAM. Epley et al. (2007) suggested that anthropomorphism increases the perceived usefulness of robots in two ways. First, facilitating anthropomorphism can encourage a sense of efficacy that improves interaction with a robot. Second, anthropomorphism can increase the sense of being socially connected to the robot and thus its perceived usefulness. The literature generally supports a positive effect of anthropomorphism on usefulness. Canning et al. (2014) found that people rated humanlike robots higher than mechanical ones on utility, and Stroessner and Benitez (2019) found that humanlike robots were perceived as more competent than machinelike ones. However, Goudey and Bonnin (2016) found this effect to be nonsignificant. In a service context, the positive effect of anthropomorphism on usefulness suggests that customers will have more confidence in the ability of more humanlike robots to provide better services.

Relational mediators

Negative affect

Defined as intense negative feelings directed at someone or something (Fishbach and Labroo 2007), feelings of negative affect a robot may elicit include discomfort such as eeriness, strain, and threat. According to Mori’s (1970) uncanny valley hypothesis, highly humanlike robots generate feelings of eeriness, and people find such robots creepy because uncanny humanlikeness threatens people’s human identity. Therefore, when interacting with highly humanlike robots, people may experience heightened arousal and negative emotions (Broadbent et al. 2011). Research shows that people perceive humanlike robots with greater unease than machinelike robots, and that children may fear highly humanlike robots (Kätsyri et al. 2015). In a service context, Mende et al. (2019) found that customers experienced feelings of eeriness and threat to human identity when interacting with a humanoid service robot and responded more negatively to a robot that was perceived as more humanlike. Therefore, anthropomorphism may not always be desirable, and to avoid causing negative emotions a robot should not be perceived as too humanlike.

Positive affect

Defined as intense positive feelings directed at someone or something (Fishbach and Labroo 2007), feelings of positive affect a robot may elicit include enjoyment, pleasure, and warmth. Marketing research indicates that anthropomorphized products and brands evoke positive emotional responses. Customers view such products and brands as more sociable and are more likely to connect to them emotionally and experience feelings of warmth (van Doorn et al. 2017). Regarding robots, van Pinxteren et al. (2019) found that a robot’s humanlikeness positively influenced customers’ perceived enjoyment. Kim et al. (2019) reported a positive effect of anthropomorphism on pleasure and warmth, suggesting that anthropomorphism enables a humanlike emotional connection with a nonhuman agent. It seems that anthropomorphism can elicit both positive and negative emotions toward a robot, with opposite effects on customer use intention, making this relationship complex.

Rapport

Rapport in this context is the personal connection between a customer and a robot (Wirtz et al. 2018). Building rapport with machines and technologies is often impossible or unnecessary; with service robots, however, it is both possible and desirable (Bolton et al. 2018). This is especially true in services, where rapport (with an employee or robot) is an important dimension in customer experience. Through anthropomorphism, people tend to perceive a robot to be more lifelike and sociable and feel a stronger sense of social connectedness, making emotional attachment to and bonding with the robot more likely. Thus, anthropomorphism facilitates human–robot rapport, making it easier, more desirable, and more meaningful. In a service context, Qiu et al. (2020) found that when customers humanize a service robot, they are more likely to build rapport with it.

Satisfaction

Satisfaction is defined as an affective state resulting from a customer evaluation of a service provided by a company (Westbrook 1987). With few exceptions, satisfaction has not been examined in HRI research. However, given the central role of satisfaction in marketing and its established influence on customers’ behavioral intentions, we include it as a mediator between anthropomorphism and customer intention to use a robot. Our discussion shows that anthropomorphism can improve people’s perceptions (e.g., perceived intelligence), evaluations (e.g., usefulness), and relationships (e.g., rapport) with a robot. Hence, we predict a positive effect of anthropomorphism on satisfaction. However, research also suggests that when a robot is perceived as more humanlike, people tend to treat it as a real person and expect it to show human intelligence. Their expectations regarding the robot’s human capabilities are increased, and they are likely to experience disappointment when the robot fails to meet those expectations (Duffy 2003).

Trust

In a service context, trust is a psychological expectation that others will keep their promises and will not behave opportunistically in expectation of a promised service (Ooi and Tan 2016). Anthropomorphism of service robots may help establishing and increasing trust. When people attribute human capabilities to a nonhuman agent, they tend to believe that the agent is able to perform the intended functions competently. In our context, this means that customers put more trust in the ability of a more humanlike robot to deliver a service. This positive effect of anthropomorphism on trust receives general support in the literature. Waytz et al. (2014) found that people trusted an autonomous vehicle more when it was anthropomorphized, de Visser et al. (2016) showed that a robot’s humanlikeness is associated with greater trust resilience, and van Pinxteren et al. (2019) confirmed that anthropomorphism of a humanoid service robot drove perceived trust in the robot. However, Erebak and Turgut (2019) found no effect of anthropomorphism on trust. Hancock et al.’s (2011) meta-analysis examined the impact of anthropomorphism on trust together with other robot attributes; the reported effect size is rather weak and nonsignificant.

Moderators of the anthropomorphism–use intention relationship

Several studies have examined moderators of the relationship between anthropomorphism and use intention. These studies have considered customer characteristics (the individual’s cultural background and feelings of social power), robot appearance and task, and situational factors (Fan et al. 2016; Kim and McGill 2011; Li et al. 2010). However, most have focused on one study context and only a few types of service robots. The present meta-analysis systematically analyzes two sets of variables that may exert a moderating influence: robot types and service contexts.

First, we focus on robot types that have a large impact on the robot’s overall appearance and behavior, as shown in Table 1. Anthropomorphism represents an important driver for customer decision-making and use intention. However, the importance of anthropomorphism may vary for different robot types since robots may display characteristics and behaviors that amplify or buffer the effect of anthropomorphism. Research in HRI has shown that robot behavior is strongly shaped by design features, in particular by physical embeddedness and morphology (Pfeifer et al. 2007). In addition, the design decision to assign features of more or less obvious gender orientation to a robot can bias perceptions of the robot because of gender-stereoty** (Carpenter et al. 2009). Another powerful design strategy pertains to the level of cuteness or the choice of a zoonotic body form for the robot. Both characteristics can endear the robot to the customer and produce a strong affective bond.

Second, drawing on task–technology fit (TTF) theory we propose that service contexts moderate the relationship between anthropomorphism and intention to use the robot (Table 1; Goodhue and Thompson 1995). TTF suggests that technology has to meet the customer’s requirements when engaging in specific tasks, such as receiving services from a robot. If the technology meets the customer’s needs during service provision (e.g., service robot anthropomorphism), the experience will be more satisfying and the customer more likely to use the technology again (Goetz et al. 2003). We examine five moderators characterizing the service context. We also control for the influence of various method moderators, as shown in Table 1.

Method

Search strategy, inclusion criteria, and data collection

We used several keywords to identify empirical papers for inclusion in the meta-analysis: anthropomorphism, humanness, humanlike, human-like, humanlikeness, and human-likeness in combination with service robots, social robots, and robots. We searched for these terms in electronic databases such as ABI/INFORM, Proquest, and EBSCO (Business Source Premier). Further, we searched in Google Scholar and dissertation databases to identify studies published in grey literature such as conference proceedings and dissertations. Next, we identified which papers cited key studies in the field that develop measures for anthropomorphism (i.e., Bartneck et al. 2009; Ho and MacDorman 2010) and which proposed conceptual frameworks including robot anthropomorphism as a key variable (i.e., van Doorn et al. 2017; Wirtz et al. 2018). We also contacted authors in the field to request access to unpublished studies. In the meta-analysis, we included studies (1) that examine the relationship between anthropomorphism of service robots with at least one other relevant variable from our meta-analytic framework, (2) that are quantitative rather than qualitative or conceptual, and (3) that report statistical information that can be used as or converted to an effect size. Studies not meeting these criteria were excluded. In total, we collected 3404 usable effect sizes reported by 11,053 customers. This information was extracted from 108 independent samples in 71 studies (Web Appendix A). The meta-analysis includes eight independent samples from three unpublished studies; one dataset was unpublished at the point of analysis and has since been published.

Effect size integration and multivariate analyses

The coded variables and their definitions are displayed in Web Appendix B. We integrated effect sizes (i.e., correlations) using Hunter and Schmidt’s (2004) random-effects meta-analytic approach. Accordingly, we first corrected the effect sizes for measurement error in the dependent and independent variables. We divided the correlations by the square root of the product of the reliabilities of the two constructs involved. Next, we weighted the measurement error-corrected correlations by the sample size to correct for sampling errors and calculated 95% confidence intervals. We also calculated credibility intervals to indicate the distribution of effect sizes (Hunter and Schmidt 2004). We used the χ2 test of homogeneity to examine the effect size distribution (Hunter and Schmidt 2004); a significant result suggests substantial variation. To test for publication bias we used Rosenthal’s (1979) fail-safe N (FSN), which represents the number of studies with null results that would be necessary to lower a significant relationship to a barely significant level (p = .05). According to Rosenthal (1979), results are robust when FSN values are greater than 5 × k + 10, where k equals the number of correlations. We complemented this test with funnel plots showing effect sizes on one axis and sample sizes on the other. An asymmetric funnel plot indicates publication bias. We also reported skewness statistics for effect sizes and the statistical power of our tests. We used moderator analysis and structural equation modeling in our meta-analysis. Web Appendix C gives more information about these multivariate analyses and the coding process of effects sizes and moderators.

Results

Results of effect size integration

We found that service robot anthropomorphism was related to various antecedents, mediators, and outcomes (Table 2). First, six out of nine tested traits/predispositions and sociodemographic variables were related to anthropomorphism (p < .05), with the strongest effects for competence (sample-weighted reliability-adjusted average correlation [rc] = .23), computer anxiety (rc = .20), and NARS (rc = .17). The effects of age (rc = −.12), customer gender (rc = .07), and prior experience (rc = .07) were weaker but still significant. We observed no significant effects for education, income, or need for interaction. We found physical robot features to display a stronger effect (rc = 51) than nonphysical robot features (rc = .35). Among nonphysical features, emotions of the robot had the strongest effect (.69), followed by voice (rc = .33), gesture (rc = .26), and mimicry (rc = .25). The effect of gaze was nonsignificant.

Second, we found that anthropomorphism was related to all robot-related and functional mediators and to some relational mediators. We found significant effects for robot-related mediators, including animacy (rc = .85), intelligence (rc = .54), likability (rc = .53), safety (rc = .31), and social presence (rc = .23). Similarly, we found significant effects for functional mediators: ease of use (rc = .25) and usefulness (rc = .32). Further, we found that anthropomorphism was related to three relational mediators: positive affect (rc = .56), satisfaction (rc = .41), and trust (rc = .19). These results provisionally indicate some mediating effects. We observed no significant effects for negative affect or rapport.

Third, we assessed the influence of anthropomorphism on intention to use the robot in future. We found that anthropomorphism was strongly related to this outcome variable (rc = .35).Footnote 3 Structural equation modeling (SEM) will therefore clarify the importance of indirect effects of anthropomorphism through mediators on this outcome relative to the direct effect.

The wide credibility intervals of many of these relationships suggest substantial variance in effect sizes. Moreover, the calculated Q-tests for homogeneity were significant in 18 out of 29 cases. For each significant averaged, reliability-corrected effect size, we calculated the FSN. Most FSNs (15 out of 23) exceeded the tolerance levels suggested by Rosenthal (1979), indicating results to be robust to publication bias. The calculated funnel plots were symmetric, further indicating that publication bias is unlikely to have affected our results. The skewness of effect sizes is similar to that of other meta-analyses (Otto et al. 2020). Most power values are larger than .5, suggesting that our tests have sufficient power to detect meaningful effect sizes (Blut et al. 2016).

Results of SEM

We tested our conceptual model using SEM, with the correlation matrix displayed in Web Appendix E as input. The matrix included 16 constructs of the meta-analytic framework, and we observed two high correlations. The first was between usefulness and intention to use; this was unsurprising, since usefulness is the key mediator in TAM, and many empirical studies on technology use have found similar effects (Davis et al. 1989). The second high correlation was between robot anthropomorphism and animacy. Again, this finding was unsurprising because of the aforementioned conceptual overlap of the two robot characteristics (Ho and MacDorman 2010). We addressed the issue of the high correlations by testing several alternative models without these variables. The results remained largely unchanged.Footnote 4 The condition number of the calculated models ranged between 4.98 and 11.42; thus, multicollinearity was not a serious issue. The final results of the model tests are given in Table 3. We tested the mediating effects in three models, one for each set of mediating factors.Footnote 5 Model 1 tests the mediating effects of the robot-related mediators, Model 2 shows the results for the functional mediators, and Model 3 reports the relational mediator results. Bergh et al. (2016, p. 478) explain that using SEM in meta-analysis “allows researchers to draw on accumulated findings to test the explanatory value of a theorized model against one or more competing models, thereby allowing researchers to conduct ‘horse races’ between competing frameworks.” Our models displayed good fit, largely confirming the findings from the descriptive statistics.Footnote 6

Regarding the antecedents of anthropomorphism, Models 1–3 in Table 3 show that customer age (γ = −.11, p < .05) and need for interaction (γ = −.19, p < .05) were negatively related to anthropomorphism, whereas NARS was positively related to anthropomorphism (γ = .21, p < .05). We observed no effects for customer gender, education, income, or anxiety. For the mediators of anthropomorphism, we found more support for robot-related mediators (Model 1) and functional mediators (Model 2) than for relational mediators (Model 3). Anthropomorphism displayed only a weak negative effect on rapport, contrary to expectations, whereas the effect of anthropomorphism on other mediators was stronger and positive. Specifically, anthropomorphism was positively related to robot intelligence (β = .55, p < .05), safety (β = .42, p < .05), and animacy (β = .93, p < .05). Again, the effect on robot animacy was the strongest among the examined mediators (Model 1). We also found that anthropomorphism was positively related to service robot ease of use (β = .39, p < .05) and usefulness (β = .14, p < .05), as shown in Model 2. Finally, we found that anthropomorphism was negatively related to rapport (β = −.08, p < .05), contrary to predictions; however, this effect was small. Among the relational mediators, we observed a strong effect only on satisfaction (β = .44, p < .05). In all three models, we found anthropomorphism to be positively related to intention to use the robot (β values ranging from .12 to .28, p < .05). Thus, when including the direct effects of mediators on this outcome, anthropomorphism had a significant effect, indicating partial mediation. We report the indirect and total effects of Models 1–3 in Web Appendix G.

Moderator analysis

Results of subgroup analysis

Table 4 shows the moderator tests for the anthropomorphism–intention to use relationship. Because we only have 30 effect sizes for this relationship, we first conducted subgroup analysis before using regression analysis. As shown, we found significant differences for moderators describing the type of service robot and type of service. Four method moderators were significant. Specifically, we found that anthropomorphism had a weaker effect on intention to use for physical than for nonphysical robots (H1a: rcphysical = .30 vs. rcnonphysical = .38, p < .05) and stronger effects for female than for nonfemale robots (H1b: rcfemale = .52 vs. rcnonfemale = .31, p < .05). Further, the effects were stronger for provision of critical than for noncritical services (H2a: rccritical = .43 vs. rcnoncritical = .30, p < .05). We found weaker effects when comparing possession-processing with nonpossession–processing services (H2b: rcpossession = .17 vs. rcnonpossession = .36, p < .05) and mental stimulus–processing with nonmental stimulus–processing services (H2e: rcmental = .28 vs. rcnonmental = .42, p < .05). However, we found stronger effects for information-processing compared to noninformation–processing services (H2c: rcinformation = .49 vs. rcnoninformation = .30, p < .05). Among the method moderators, we found significant differences for publication outlet, publication status, and marketing journal. The effects were weaker in studies published in journals (rcjournal = .29 vs. rcnonjournal = .43, p < .05) and in published rather than unpublished studies (rcpublished = .31 vs. rcunpublished = .57, p < .05). They were stronger in marketing than in HRI journals (rcmarketing = .39 vs. rcHRI = .32, p < .05). Further, the continuous moderator study year was positively correlated with effect sizes (r = .58, p < .05), suggesting stronger effects in later studies. The other moderators were nonsignificant.Footnote 7

Results of metaregression

We validated these results using a metaregression (Grewal et al. 2018) in which we regressed the effect sizes on the 10 moderators significant in the subgroup analysis (Table 5). We observed stronger effects for female than nonfemale robots (H1b: β = .16, p < .05). We found weaker effects for possession-processing than nonpossession-processing services (H2b: β = −.25, p < .05) and for mental stimulus-processing than nonmental stimulus-processing services (H2e: β = −.10, p < .10). Also, the effects were stronger in later studies because study year was significant (β = .06, p < .05). The direction of these moderating effects was in line with results of the subgroup analysis.Footnote 8 No differences were observed for other moderators. The moderators explained 73% of the variance in effect sizes. In addition, multicollinearity among the moderator variables was low, the largest variance inflation factor (VIF) being 6.910. Figure 2 summarizes the results of the SEM and metaregression.

Overview of key meta-analytic findings on robot anthropomorphism. Notes: The figure shows the results of SEM and metaregression (including significant relationships between anthropomorphism and other constructs only). The estimates refer to different SEM models (Model 1/Model 2/Model 3). All estimates are significant at the .05-level, except mental stimulus-processing services which is significant at the .10-level. The dotted lines suggest further significant relationships (not shown here to ease readability)

Discussion

The present meta-analysis enhances understanding of service robot anthropomorphism. We developed and tested a comprehensive framework of antecedents, outcomes, and context variables relating to the impact of anthropomorphism on intention to use a service robot. By develo** and testing such a comprehensive meta-analytic model, our study clarifies the role of anthropomorphism in customer use intention of robot technology, its underlying mechanisms, and the influence of contextual moderators. The findings provide new insights and raise questions for future research. First, it was initially unclear whether anthropomorphism exerts a positive or negative effect on customer intention to use a robot. This study clarifies that anthropomorphism exerts a strong positive effect (Tables 2 and 3), as anthropomorphism theory suggests (Duffy 2003). It seems that humanlike perceptions are more likely to facilitate human–robot interactions, hel** customers to apply the familiar social rules and expectations of human–human interactions (Zlotowski et al. 2015). This finding emphasizes that robot anthropomorphism is important for service scholars studying customer interaction with this technology. We recommend that scholars employ anthropomorphism theory more often, since it explains customer reactions to service robots better than does uncanny valley theory.

Second, we clarify the mediating mechanisms between robot anthropomorphism and customer use intention. Following Bergh et al. (2016), we used meta-analysis to carry out a “horse race” and examine the explanatory power of one theoretical model versus competing models (Tables 2 and 3). We found that five major robot characteristics proposed by HRI research represent important robot-related mediators (Bartneck et al. 2009). Specifically, the robot characteristics of animacy, intelligence, likability, safety, and social presence are vital mediators, which elucidates the mechanisms by which anthropomorphism translates into future use intention. Similarly, we found that the two functional mediators proposed by technology acceptance research – usefulness and ease of use – are essential for understanding the operating mechanism of anthropomorphism (Davis et al. 1989). These mediators have received extensive attention in the technology acceptance and service literature, and our study clarifies their importance for service robots; recently developed models, such as the service robot acceptance model (Wirtz et al. 2018), should therefore be extended regarding these mediating effects. We also tested several relational mediators from the relationship marketing literature, but found less support for them (Tables 2 and 3). Although robot anthropomorphism is related to customer satisfaction and positive affect, its relationship with negative affect was nonsignificant and the relationship with rapport was negative. Scholars should therefore rethink the measurement of these mediators in service robot contexts. It may be that more specific relational mediators are required and that researchers need to specify the kinds of negative feelings that anthropomorphism may induce (e.g., tension, worry). Similarly, rapport may be induced by robot anthropomorphism only when interacting with a robot over a longer period, necessitating longitudinal research designs. The model comparison of our meta-analysis provides insights into not only the existence of mediating mechanisms but also their order, direction, and magnitude (Bergh et al. 2016). Unless they consider the mediators identified here, scholars will not fully understand why customers use service robots and may overestimate or underestimate the importance of anthropomorphism.

Third, we assessed the moderators influencing the anthropomorphism–intention to use relationship using meta-regression (Table 5). We considered two sets of contextual moderators and one set of method moderators, and found differences depending on the type of robot employed by the service firm. Anthropomorphism had stronger effects for female than for nonfemale robots. Scholars should extend these findings to assess, for instance, how female customers react to male robots and vice versa. Regarding service type, we observed several factors influencing the importance of anthropomorphism as a predictor of use intention. We found Wirtz and Lovelock’s (2016) service classification useful in this context. Specifically, anthropomorphism is more important for information-processing than for possession-processing and mental stimulus-processing services. We used task–technology fit theory to justify these effects. Scholars are therefore encouraged to apply established concepts in the service literature (e.g., service recovery) to robot research. The moderator results were robust when considering the influence of method moderators such as publication outlet and status, marketing journal, and study year. Regarding the latter moderator, it seems that anthropomorphism gained importance as a predictor of use intention in recent years. While some of the other robot and service type moderators were significant in subgroup analysis (Table 4), they were nonsignificant in meta-regression.

Fourth, we assessed the antecedents of anthropomorphism in order to understand which customers were more likely to anthropomorphize service robots (Table 3). The literature recognizes that customers anthropomorphize all kinds of marketing objects, including brands, products, and services; we contribute to this literature by testing the influence of various customer characteristics on robot anthropomorphism. We found that NARS, need for interaction, and customer age in particular are related to robot anthropomorphism. Some antecedents have only been assessed in descriptive statistics (Table 2); these analyses suggest further effects of customer competence, prior experience, and different physical and nonphysical robot features, such as gesture, mimicry, and voice of the robot. We explain these effects using Epley et al.’s (2007) theory of anthropomorphism, which is useful for analyzing why some customers are more likely than others to anthropomorphize robots.

Managerial implications

This meta-analysis has several implications for marketing managers intending to employ service robots on the front line and adhering to “honest or ethical anthropomorphism” (Leong and Selinger 2019; Thomaz et al. 2020) – the design of robot features to resemble human body/behavior with no intention to deliberately mislead users. First, our findings highlight to managers the potential consequences of employing humanlike versus machinelike robots in service firms. Since we found mainly positive effects associated with anthropomorphized service robots, managers should not worry that an uncanny valley effect will lead customers to decline to use service robots. Anthropomorphism is positively related to important outcomes including ease of use, usefulness, safety perception, and social presence, and it does not lead to the experience of negative affect. However, anthropomorphism is not positively related to rapport, which indicates that service robots may not (yet) develop a personal connection with customers (Wirtz et al. 2018). Therefore, when personal connection is key to a firm’s business model, managers should employ human employees together with service robots. Managers can use the framework of this meta-analysis to comprehensively assess the reactions of various customers to service robots in customer surveys and focus groups.

Second, our meta-analysis helps managers to establish the service contexts in which it is most important to employ humanlike versus machinelike robots. Managers should employ humanlike robots for critical services including ticket selling and shop** advice in retailing; for uncritical services, robot anthropomorphism is less important. Similarly, humanlike robots should be employed for information-processing services such as banking and financial services; anthropomorphism is less important for encouraging customers to use robots for possession-processing or mental stimulus-processing services. Managers in the latter industries therefore have less need to invest in humanlike service robots and monitoring customer–robot interaction.

Third, our results will guide managers on which humanlike robots to choose when offering services to customers. We suggest that service firms employ female gendered rather than male gendered service robots (e.g., robots with a female look, name, and voice). However, managers can choose any robot size, level of cuteness, and even zoonotic body form, since no differences were observed for these robot types.

Fourth, managers can use these findings to identify which target customers are most receptive to the employment of humanlike robots. They should pay particular attention to customer traits and predispositions, including customer anxiety, negative attitude toward robots, and competence in using technology, and we recommend that they complement these criteria with sociodemographic variables such as customer age and gender. However, education, income, and need for interaction are less important for segmenting and targeting potential customers of robot services. Managers can also use our findings to assess whether their own customer base is ready for robot services. Finally, the results reveal which robots are most likely to be anthropomorphized by customers depending on different physical and nonphysical robot features (e.g., gesture, mimicry).

Future research agenda

While our discussion section provides insights on concepts that have already been explored in the context of anthropomorphism (“what we already know”), this section will focus on themes that have been neglected by extant literature (“what we do not know, but should know”). Table 6 presents exciting avenues for future research derived from the findings of our study and the lack of studies in current body of literature.

Consider novel and untested outcomes

We find support for the idea that anthropomorphism positively impacts intention to use the robot. As this research field is still develo**, there are many interesting avenues for research that have not been fully explored. In particular, we could not explore relationships between anthropomorphism and outcome variables including willingness to pay for a service or purchase behavior, since such data is lacking. Thus, we urge future research to explore other outcomes of anthropomorphism beyond use intention that are relevant in a marketing context. For example, perceptions of a service robot may spill over to the firm or brand that employs the robot. Research has just begun to explore how service robots’ perceptions impact perceptions such as brand trust and brand experience (Blut et al. 2018; Chan and Tung 2019). Research shows that if other humans are unavailable, and customers feel isolated, they will be more accepting of brands as sources of affiliation (Mazodier et al. 2018). Future studies should explore the role of brands in services delivered by robots, including the service robot–brand fit or alignment. Moreover, it would be interesting to assess nontraditional outcomes from transformative research such as customer literacy, loneliness, and learning as well as outcomes that may not be intended by managers, but are hampering customers’ well-being (Schneider et al. 2019). Thomaz et al. (2020) proposed that technology with humanlike features has the potential to nudge customers toward greater self-disclosure. It also can lead to a decrease in self-control, for example in consuming unhealthy products (Hur et al. 2015). Future studies should explore these and other “dark-side” effects, such as the impact of anthropomorphism on customer vulnerability and self-image. In addition, firms may use robots rather than employees for services such as complaint management. Beyond that, future research should address the following questions: Will service robots prevail in future as substitutes of human service providers, or will they augment a personally delivered service? Will customers use nonhuman service delivery across whole sectors, such as health care? How will this change customer expectations toward service quality?

Test theoretically meaningful mediators

We identified robot characteristics, functional characteristics, and some relational characteristics as important mediators in our model, as suggested in the marketing and HRI literature. We limited our analysis to mediators reported in extant studies. Scholars should build on this by carefully selecting and testing other meaningful mediators, such as different types of negative affect (e.g., tension, worry, and anger) and commitment (e.g., affective and calculative). In addition, it would be interesting to assess serial mediation in robot acceptance models (e.g., functional mediators impacting relational mediators), since these models were too complex for our SEM. These studies should also consider nonlinear effects of mediators on intention to use, although the nonlinear effect in our study was nonsignificant. Perhaps models considering novel mediators would display the expected nonlinear effects.

Broaden the scope of antecedents and test their interactions

We found robot design features and some customer characteristics to impact the extent to which customers anthropomorphize service robots. We could not differentiate between physical robot features (e.g., head, eyes, arms, legs), nor could we test interactions between these and other design features and customer characteristics. Future studies should also use Epley et al.’s (2007) theory of anthropomorphism, as per our study, and assess the antecedents of elicited agent knowledge, effectance motivation, and sociality motivation proposed in this theory. Studies should assess whether these antecedents equally impact the robot’s anthropomorphism in terms of its appearance, movement, and speech. Further, some antecedents may be contextually relevant only. Customers may react to robots differently when they are accompanied by someone else versus being alone with the robot. Since customers have limited experience with robots, it is likely that the importance of predictors will change over time (Venkatesh et al. 2012).

Consider novel moderators and more complex moderating effects

We tested a number of moderators related to the robot type and service context; however, several of these moderators were nonsignificant. Future studies should test novel moderators measured at the individual customer level (e.g., proactive vs. reactive robot interaction; preference for personal space), or at the study level (e.g., national culture and emerging markets). In meta-analyses it is often difficult to assess customer-level moderators such as the need for interaction, tendency to anthropomorphize objects, and type of interaction (e.g., duration of interaction). Future research should test more complex moderating effects at the individual level (e.g., how female customers react to male robots and vice versa). At the study level, the international business literature proposes various frameworks to assess cross-national differences that may impact the effects of anthropomorphism (Swoboda et al. 2016). Most studies have been conducted in only a few countries, with a focus on the US. Scholars should thus consider additional country differences using primary data. Similarly, scholars could test other service classifications based on TTF theory, since this theory has proven useful.

Consider alternate drivers of service robot use in different service contexts

We examined the same antecedents for all service types in our model and found some significant effects; however, it may be that certain unique determinants of anthropomorphism only matter in some contexts. Future studies should therefore develop unique models for different service contexts (e.g., hedonic, emotional, and temporal services). For example, variables related to intrinsic motivation, such as control, curiosity, enjoyment, immersion, and temporal dissociation, have been shown to serve as antecedents to usefulness perceptions and behavioral intentions of hedonic information technology (Agarwal and Karahanna 2000; Lowry et al. 2012). These variables could also explain service robot usage in hedonic contexts, such as robots in waiting areas to entertain waiting customers. To further understanding, future research should consider differences in the perceptions of human–robot interaction at different stages of the customer journey and explore how encounters at different stages impact customer behavior (Hoyer et al. 2020; Hollebeek et al. 2019). When interactions with service robots are longer and more intensive, studies should explore how customers experience robots through their senses, how this impacts their perception of the robot as product vs. a living entity, and how it affects “robot quality” perceptions. Also, it would be interesting to explore which emotions arise if customers have more intensive and more frequent interactions with the same robot. Perhaps, they will perceive a sense of ownership. Addressing this aspect and exploring the context of service robot ownership and possession could also be a fruitful research avenue.

Use different research designs

Future research should use more diverse research designs. Many studies considered here were conducted in lab settings or via surveys and few measured actual customer behavior. Studies should use longitudinal designs and assess whether anthropomorphism impacts use intention differently at different stages of technology use (i.e., assimilation, diffusion, routinization). Scholars should sample customers from underresearched contexts (e.g., educational robots) to study contextual differences. We also recommend the use of more qualitative methods to identify new factors impacting anthropomorphism.

We hope scholars will find this research agenda inspiring, and that more scholars engage in studying this exciting and important field.