Abstract

We test for differences in subjective well-being across four pre-defined generations in Australia born between 1928 and 1994: The Lucky Generation, Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y. We focus on overall life satisfaction and range of domain satisfactions. We find that Baby Boomers are less satisfied with life than thosce born before and after them. We observe similar patterns when considering domains such as finances and housing. However, differences in satisfaction with employment opportunities show the opposite pattern, with Baby Boomers and Generation X’s reporting higher satisfaction as compared to the Lucky Generation and especially those from Generation Y. Family and labour marketcv status have greater effects than cohort of birth on many of the domains studied; however, the cohort effects are significant and non-negligible, particularly concerning satisfaction with life, employment opportunities, and housing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Individuals’ responses to questions about their subjective well-being represent more than just an assessment of the current situation. Apart from aspects related to their personality, socio-demographic characteristics, and other everyday life experiences, the socio-cultural environment and historical moments individuals grew up in are also likely to affect how they rate their well-being. Hence, 60-year-old individuals may report lower subjective well-being than 40-year-old ones because of (a) the effect of ageing, (b) the different moments in time they may have been interviewed, but also (c) because they belong to different birth cohorts.

Ryder (1965) argued that studying cohort differences-and by extension generational differences-enables an understanding of social change. A generation is defined as a distinguishable group of individuals, which shares birth years, place, and significant life events at different developmental stages. These groups develop a unique pattern of behaviour and life perceptions based on these common experiences (Bardo, 2017). In essence, cohort differences constitute a significant source of social difference, which significantly impact individuals’ perceptions towards life (Ryder, 1965; Roger, 1982; Settersten, 2002; Yang, 2008; George, 2010). Thus, the essence of subjective well-being is likely to vary across cohorts.

In this paper, we use Australian longitudinal data to test for subjective well-being differences across generations. To date, few studies have explicitly studied generational differences in subjective well-being. Yang (2008) used US data from the General Social Survey (GSS) for 1972–2004 to study happiness differences over the life course and over time. Yang uses hierarchical age-period-cohort models, and finds that the Baby-Boomer cohort reports lower happiness than other birth cohorts. Similarly, de Ree and Alessie (2011) find that although the detrended cohort profile tends to be highest among the younger and older cohorts, no meaningful pattern could be observed (based on the German Socio-Economic Panel-GSOEP). Bardo et al. (2017) also emphasised the general finding that Baby Boomers tend to report lower well-being than cohorts before and after them and, as Yang (2008), report a similar pattern using GSS data.

This study contributes to the existing literature in at least three ways. First, we use Chauvel’s (2011, 2012) age-period-cohort-detrended (APCD) approach to identify and estimate non-linearities in all available age groups, periods and cohorts, with our primary interest in birth cohort (generation) differences. The longitudinal nature of the Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey allows to detect subjective well-being differences across four theoretically defined generations in Australia (i.e., The Lucky Generation (1928–1945), Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Generation X (1965–1979), and Generation Y (1980–1994)).Footnote 1 We extend Yang’s (2008) approach and focus on distinct cohort patterns but also report on age and time trends.

Second, the frequent interchangeable use of subjective well-being termsFootnote 2 has made it challenging for previous research to fully understand the effects of birth cohorts on particular subjective well-being constructs. Yang (2008) warned about simplifying her cohort effects’ results on happiness to different subjective well-being measures. Thus, we provide further insights by focusing not only on life satisfaction but also on a wide range of domain satisfactions available in the HILDA data, namely satisfaction with employment opportunities, finances, housing, health, leisure, safety, neighbourhood, and local community. Differences in formative life experiences can affect the relative importance of domain satisfactions within and across cohorts (Bardo & Yamashita, 2014). Thus, we expect to observe relative differences in levels of domain satisfaction across generations.

Finally, to understand the relevance of the birth cohort effects relative to other socio-economic characteristics, we further control for gender, education, income, family, health and labour market status, and place of residence. These covariates are all related to overall life satisfaction and its various domains. Yet, the cohort effects are significant and non-negligible, particularly concerning overall life satisfaction, satisfaction with employment opportunities and housing. These findings may have important public policy implications for younger generations especially.

Background

A growing strand of literature examines how subjective well-being varies as individuals age while also adjusting for potential period and cohort effects (see for example, Rodgers, 1982; Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008; de Ree & Alessie, 2011; Fukuda, 2013; Tang, 2014; Bardo, 2017; Bauer et al., 2017; Zhang, 2020). These studies considered cohort differences in subjective well-being as a secondary objective to focusing on age or period but did not systematically analyse cohorts differences within the context of pre-defined and theoretically meaningful generations.

Research on cohort effects suggests that time-specific macro-level factors reflected in cohort variations play a significant role in influencing individual subjective well-being (George, 2010). Various academic contributions have tried to explain these changes across birth cohorts. According to the post-materialist hypothesis, economic development has brought wealth and financial security, making individuals less economically dependent on family and community and giving them the opportunity for self-realisation (Inglehart & Baker, 2000). This shift in values is associated with smaller increases in well-being among more recent cohorts (Rodgers, 1982). Yet, Easterlin (1987) relates the size of birth cohorts to subjective well-being. Larger cohorts are more likely to face greater competition for education and jobs, which acts as pathways towards higher levels of subjective well-being. In contrast, Ryder’s (1965) proposition highlights that individuals are most sensitive and influenceable during their formative years (e.g., childhood and young adulthood). A difficult childhood may result in lower subjective well-being.

One way to better understand the impact of generational membership on these changes is by separating the population into generations and looking at their different socio-economic experiences. Based on information provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), we categorise Australians born from 1930 to the early 1990s in four different generations: (1) the Lucky Generation (1926–1946) which experienced full employment and prosperity during the post-World War II economic boom; (2) the Baby Boomers generation (1946–1964) which, as in many developed economics, lived through enormous social change (e.g., rising rates of female labour market participation, and marital separation) and was exposed to world events including the Cold War, the Vietnam War, the sexual revolution and peace movements; (3) Generation X (1965–1979), which is seen as a ‘bridge generation’ and is regarded as having fewer opportunities than their Baby Boomer predecessors and feeling closer in age to the next generation members (Generation Y) and so can connect somewhat with their culture, views, and even values; and (4) Generation Y (1980–1994), or Millennials, who grew up in the era of globalization and techological progress.

Data and Variables

Data

We use data from 18 waves of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) survey, covering the period 2001–2018. The HILDA Survey is a household panel study collecting annual information from individuals from the same households since 2001. The HILDA Survey sample was drawn following a complex, probabilistic design, and is largely representative of the population aged 15 and older in Australia (Summerfield et al., 2019). Our sample is reduced to individuals aged between 19 and 78.Footnote 3 We thus use an unbalanced panel of 31,653 individuals from a total of 253,986 person-year observations.Footnote 4

Variables

To measure subjective well-being in the HILDA Survey, respondents are asked to rate their satisfaction on a 0–10-point scale. For example, the overall life satisfaction question asks: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life overall?” Domain satisfactions are rated on the same 11-point scale as life satisfaction. The relevant domains we consider, as available in the data, are satisfaction with employment opportunities, finances, housing, safety, leisure, health, feeling part of the local community, and neighbourhood.

The main independent variables measure age, period and birth cohort. The respondents’ birth cohorts are calculated by subtracting age from the year of the survey. Cohort variables were constructed to be consistent with previous research and with the orthogonal requirements of the age–period–cohort models described in Analytical Method (Chauvel, 2011; Chancel, 2014; Chauvel & Schroder, 2015). We conducted initial sensitivity tests to find the optimal cut-off values for the age–period–cohort variable grou**. Cohorts were cut in 3-year intervals spanning the period 1928 to 1994, to alleviate possible instability linked to measurement range and observation sizes within groups (Luo et al., 2016). Birth cohorts were further grouped into the four different generations (i.e., Lucky generation, Baby Boomers, Generation X and Generation Y). For the sake of consistency, the period variables were also divided into 3-year intervals.

Key individual-level variables that we also control for include the respondent’s sex (female = 1; male = 0), immigrant background (immigrant = 1; Australian born = 0), and education, which is coded as two dummy variables (less than a high school degree (CHS) and college education or more; reference = CHS and Diploma/Cert 3–4). We also adjust for other characteristics expected to be correlated with subjective well-being. Household income is coded as two dummy variables indicating the lowest and highest terciles (reference = middle tercile) in family income (converted to December 2018 prices and adjusted for family size). Marital status categories include married (reference), de facto relationship, separated, divorced, widowed, and never married. For health status we use the SF–36 measure of general health with scores from 0 to 100. We define a person as being in poor health if their SF-36 score is less than or equal to 37, on the basis that approximately 10% of the population are at or below this threshold. Employment status includes employed (reference), unemployed, not in the labour force and full-time student. Number of children is dichotomized as having one or more children (= 1) versus having no children. Religious involvement is measured by frequency of attending religious services, which ranges from never (0) to several times a week (8). Finally, place of residence includes: Major city and Inner regional (reference) and outer regional or remote.

Analytical Method

In general terms, Age–Period–Cohort (APC) models explain outcomes through the combined effect of three components: the individual’s age a (\({\alpha }_{a}\)), birth cohort c (\({\gamma }_{c}\)), and period of measurement (\({\pi }_{p}\)) such that:

Thus, an APC model can detect how an outcome is explained by position in the life cycle (age effect), the date of birth (cohort effect) and the time of measurement (period effect). Although empirical estimations of the three effects have been proposed (Fienberg & Mason, 1979; Mason et al., 1973), an ‘identification problem’ besets all APC models (Glenn, 2005; Mason & Wolfinger, 2001): because age = period – cohort, each variable is a combination of the other two. Because of this collinearity, no statistical model can solve this inherent indetermination (Holford, 1991; Luo, 2013).

In our analysis, we rely on the APC-detrended (APCD) model developed by Chauvel (2011, 2012).Footnote 5 The APCD model recognizes that linear trends in APC models cannot be robustly attributed to age, period and cohort. Therefore, it identifies cohort effects by assuming a set of constraints where the age, period, and cohort parameters have a zero-sum and zero-slope shape, and where the first and last cohort are excluded (Chauvel, 2011, 2012). These constraints absorb the linear age, period, and cohort trends, which allow the model to estimate the detrended age, period, and cohort effects. Thus, the “detrended” approach focuses on how the effects of age, period and cohort fluctuate around a linear trend. The APCD method shows how different cohorts (averaged over the available lifespan of the cohort) diverge from the linear trend.Footnote 6

We investigate whether individuals born in different years (birth cohort) report significantly lower or higher levels of subjective well-being, suggesting differences in the influence of early life conditions and formative experiences. Hence, we consider the dependent variable [yiapc], observed in all years, for individual i of age a in period p and belonging to cohort c = p – a. The latter equation indexes the vectors of coefficients \({\alpha }_{a}\), \({\gamma }_{c}\) and \({\pi }_{p}\). Including constraints, the model is written as:

where \({\alpha }_{a}, {\pi }_{p}, {\gamma }_{c}\) are, respectively, age, period, and cohort effect vectors, which reflect the non-linear effect of age, period, and cohort. These have two main constraints: each vector sums up to zero and has a zero slope. This implies that these vectors are null when the age, period, or cohort effects are linear. The terms \({\alpha }_{0}rescale\left(a\right)\) and \({\gamma }_{0}rescale\left(c\right)\) absorb the linear trends. The rescaling is a transformation that standardizes the coefficients \({\alpha }_{a}\) and \({\gamma }_{c}\) by transforming age from the initial code \({a}_{min}\) to \({a}_{max}\) to the interval -1 to + 1. Finally, as the first and last cohorts appear just once in the model (the oldest age group of the first period and the youngest of the last), their coefficients are unstable; we obtain better estimates by excluding them.

The model also includes several socio-economic covariates (\({x}_{j}\)) as described in the previous section. The main explanatory variable of interest is the detrended cohort effect \({\gamma }_{c}\) where estimates that are statistically different from zero are independent cohort effects. We estimate the models both with and without covariates (full results are provided in Tables 2 and 3 in the Appendix).Footnote 7 A comparison of the results between these two models indicates the degree to which cohort effects are the consequence of changes in population characteristics or not.

Two important limitations of the APCD model are worth highlighting (Vera-Toscano & Meroni, 2021b). First, the APCD model estimates cohort effects. Thus, results are more informative for cohorts we repeatedly observe in the data, as these estimates can be understood as lifetime effects. In contrast, the model provides estimates for part of their lifetime for more recent cohorts (and the oldest cohorts), who are observed fewer times in the data. If we believe that more recent/older cohorts will not progress linearly, then the APCD results may be less informative. Second, APCD models imply the existence of cohort effects but do not indicate to what extent these differences are stable, increase, or decrease over the life cycle of a given cohort. Accordingly, we complement the APCD analysis with two graphs: (1) a ‘synthetic cohort’ diagram and (2) a ‘cohort diagram’. The ‘synthetic cohort’ graph shows the development of the relevant variables for different birth cohorts over the years, hel** to examine the degree of change in opinion over these cohorts’ lives. Alternatively, ‘cohort diagrams’ compare different cohorts at the same age. These diagrams identify differences between birth cohorts for each age category studied.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 reports summary statistics on the responses to life satisfaction and the satisfaction domains by age group, year of observation, and birth cohort. In addition, the first column provides the share of individuals represented in each age, year and cohort group. Results show that birth cohorts related to the Lucky Generation are smallest (comprising 12% of our sample), whereas in our sample the cohorts relating to the Baby Boomer generation and Generation X are the largest (31% and 35.1% respectively).

Regarding life satisfaction, individuals report lowest life satisfaction when they are 40–42 years old, after which it starts to increase and reaches the maximum reported level at 70–72 years old (Table 1, Panel A). For domain satisfactions we find that satisfaction with finances, housing, neighbourhood and local community tend to increase as individuals age. The opposite trend is observed, as expected, for satisfaction with employment opportunities and health. Satisfaction with leisure time is stable across different ages, and for safety satisfaction we observe high levels except for those aged 37–48 years old.

Regarding changes across time (Panel B), whereas life satisfaction seemed to decrease between 2004–2009 to rise again in recent years, satisfaction with finances, housing, leisure, safety and neighbourhood displayed an increasing trend. We observe a decrease in health satisfaction in recent years. Surprisingly, satisfaction with employment opportunities was highest in 2007–2009 (during the GFC), after which it declined and began rising again in 2016–2018. No clear pattern is observed for satisfaction with the local community across time.

Results in panel C show that life satisfaction is lowest for individuals born between 1964–1969, sligthly increasing for younger cohorts. Younger cohorts report higher values of satisfaction with employment opportunities, health, and safety, whereas they report lower values than their older counterparts in satisfaction with finances, housing, neighbourhood and local community.

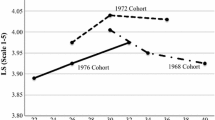

To gain further insights into how birth cohorts’ subjective well-being evolves across time and to compare them to each other, we construct ‘synthetic cohort’ and ‘cohort diagrams’ for life satisfaction. In Fig. 1, we present changes in overall life satisfaction for different birth cohorts over observation periods. Given that we use 3-year intervals and there are up to 20 cohorts, to better identify trends not all cohorts included in the analysis are shown in Fig. 1. The oldest cohorts born between 1928–1930 or 1937–1939 report the highest levels of overall life satisfaction in each survey year. Those born between 1964–1966 have the lowest life satisfaction, whereas the younger cohorts on average report higher life satisfaction over time. Figure 1 therefore suggests that the middle birth cohorts, especially comprising the Baby Boomer generation, report the lowest levels of life satisfaction.

Figure 2 displays differences life satisfaction across different birth cohorts given certain ages. Overall, for those aged 70 or older, there is only a slight decline in life satisfaction over time. Such declines become more noticeable across cohorts for those aged between 52 and 64 (from age groups 52–54 to 64–66). In contrast, for those aged 49 (age group 49–51) life satisfaction remains roughly flat whereas for younger persons we observe an increase in life satisfaction as they age.

Figure 1 showed overall life satisfaction differences across birth cohorts given certain periods without controlling for their age, whereas Fig. 2 showed cohort differences in life satisfaction given certain ages without controlling for the periods of observation.Footnote 8 In the next sub-section, we report the results from estimating differences in overall life satisfaction across birth cohorts after controlling for both age and period effects, as well as selected control variables.

APCD Models: Overall Life Satisfaction

We begin with a general analysis of the APCD results. This analysis shows relative changes in overall life satisfaction concerning the linear trend, revealing which age, period or birth cohort categories report significantly higher or lower life satisfaction compared to other groups.

We first estimate a model of life satisfaction for person i of a (age), c (cohort) and p (period) without controls, after which we introduce control variables in a second model. Figure 3 shows the results. The period effects in the model without controls (top left) show the relative effects of economic fluctuations. Recalling that period coefficients are in 3-year intervals, there is a positive peak for the period 2001–2003, a negative one for 2007–2009 and another positive peak in the most recent 2016–2018 period. A similar pattern is observed in the model with control variables (top right), in which the nonlinear slope maintains the same overall shape.

APCD results for overall life satisfaction. Statistical years were coded as representative 3-year periods for methodological reasons (see Analytical Method). Because the focus of this paper is on birth cohort differences, periods are also presented in 3-year intervals. The model with controls is adjusted for sex, immigrant status, education, income, marital status, health status, work status, number of children, religious involvement and place of residence. The vertical axis shows the APCD coefficient, and the horizontal axis shows the range of each APC component. Dotted lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals. The four sections divided by the red vertical reference lines in the bottom right Figure broadly denote the four different generations. Starting from the left, the first cohort group is the Lucky Generation, followed by the Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y

The age effects show a U-shaped relationship between life satisfaction and age, where the middle-aged are the least satisfied with life and the youngest and oldest age groups are the most satisfied (middle left and middle right). However, results appear more consistent with a cubic relationship between age and life satisfaction, with life satisfaction decreasing again at old age; typically, after 70. This cubic relationship between life satisfaction and age is consistent with what de Ree and Alessie (2011) reported. Introducing control variables intensifies the age effects, though the shape of the figure is very similar as the deviation relative to the linear trend persists. Thus, the composition of the different age groups in terms of these socio-economic and demographic characteristics is not the source of the observed bumps in life satisfaction.

The results with respect to cohort effects show that cohorts born between 1958 and 1969 report the lowest levels of life satisfaction, whereas older and younger generations are more satisfied with life. The strongest negative effects are for the birth cohorts of 1958–1960 (-0.164 points on the 0–10 scale) and 1967–1969 (-0.163 points). The largest positive effects are for birth cohorts of 1928–1930 (+ 0.159 points) and 1994–1996 (+ 0.19 points). Starting at the 1946 cohort, older cohorts cross over from a positive to a negative trend, and the increase back to a positive life satisfaction score is observed from the 1985 birth cohort onwards. Controlling for socio-economic and demographic characteristics hardly changes the pattern of cohort effects. This suggests that the birth cohort non-linearities in overall life satisfaction do not derive from individual characteristics (even in terms of health, work status, or family composition) but from other sources, such as unobserved cohort specific contexts.

To better illustrate the regression results, the bottom right graph in Fig. 3 plots the cohort effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals, including red vertical lines, which help distinguish the four generations identified in Australian society according to individuals’ birth cohorts. Consistent with Yang (2008) and Bardo et al. (2017), Australia’s Baby Boomer generation is less satisfied with life than the generations before and after them (see Conclusions for further discussion). This also seems to be partly true for early Generation X’s; Baby Boomers and (early) Generation X’s are less satisfied with life than the generations before and after them relative to what would have been a linear trend.

Overall, the APCD results confirm that generational differences are significant when explaining life satisfaction. Yet, to better understand the relevance of cohort effects in relation to other control variables, we compare them in Fig. 4. Thus, for overall life satisfaction, individuals born in the 1994–1996 cohort are 0.345 points apart from those born in 1958–1960. This effect is stronger than being female (+ 0.101), being an immigrant (-0.094), and even by level of education and family income, among others. However, the effect of having poor health is almost 2.5 times as strong (and similar results apply to being separated). In Australia, however, being part of the least satisfied birth cohort, compared with the most satisfied one, diminishes life satisfaction more than being an immigrant, having an University degree, being in the lowest family income tercile or not in the labour force, but not quite as much as being separated, divorced, single or unemployed. In summary, birth cohort effects are stronger than many of the control variables included in the analysis, which confirm the importance of understanding cohort differences in overall life satisfaction.

APCD Models: Domain Satisfactions

As with life satisfaction, we repeated the same exercise for each satisfaction domain assuming the same set of control variables for each of them. Figure 5 presents the cohort effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals, which shows the deviations of each domain satisfaction from the linear trend across the four generations. The vertical reference lines conform to the same generations as in Fig. 3.

Generational differences in satisfaction domains. The four sections divided by the vertical reference lines denote the four different generations. Starting from the left, the first cohort group is the Lucky generation, followed by the Baby Boomer generation, Generation X, and Generation Y. Addtionals controls included

In general, the patterns for most domains are relatively consistent with the pattern observed for overall life satisfaction. Cohorts belonging to the Baby Boomer generation and Generation X are, in general, below the long-run trend of satisfaction with finances, housing, and leisure. Individuals born between 1958–1963 (and to a lesser extent 1955–1957) are the furthest below the long-run trend. Early Baby Boomers (cohort born between 1946–1954) are above the long-run trend of satisfaction with safety, local community, and neighbourhood. However, late Baby Boomers and those from Generation X are below the long-run trend of these satisfaction domains. No clear pattern is found for these two generations regarding satisfaction with health. Interestingly, in contrast to the other domains, satisfaction with employment opportunities displays an inverse U-shape pattern. Cohorts belonging to the Baby Boomer generation are well above the long-run trend and this situation is held by most of the cohorts belonging to Generation X, though their (positive) deviation is smaller but still significant. Cohorts born after 1975 are below the long-run trend and this deviation increases among the younger cohorts observed (Generations X and Y).

These results contradict to some extent those found in the USA (Slack & Jenson, 2008) where greater underemployment and more labour force competition may be at the core of less happy Americans. After World War II, Australia experienced significant economic prosperity and critical policy improvements that helped Baby Boomers. However, the generations following them face changing social and economic circumstances that are challenging Australia’s relatively stable economic prosperity (Daley et al., 2014; Kendig, 2017). Millennials face greater job instability and greater competition-driven in part by rising female labour force participation-for jobs as compared to previous generations. According to Harrington et al. (2015), millennials have high expectations regarding issues such as work-life balance and career advancement, and also value job security (Dries et al., 2008).

To complete our analysis, we further provide some results that compare cohort effects with other significant control variables for each domain satisfaction (see Fig. 6). For employment opportunities, members of the most satisfied 1949–1951 cohort are 0.6 points apart from the least satisfied 1982–1984 cohort. This is comparable with being in poor health (-0.768). However, it is larger than any of the coefficients of gender, immigrant background, level of educational attainment, family income, marital status, regional residence or importance of religion. As expected, it is much smaller than the labour market status effect, particularly being unemployed (-2.393 points).

For satisfaction with finances, the largest difference is found between members of the least satisfied 1967–1969 cohort and the most satisfied 1988–1990 (0.315 points). However, this difference is smaller than any coefficients of the additional covariates used (except of the presence of children, regional residence and religious importance). For housing satisfaction, the largest difference between cohorts is 0.37 points (between those born 1934–1936 and 1958–1960). This is larger than any of the coefficients of additional variables used except for dummies controlling for being separated or divorced. Finally, regarding satisfaction with local community, neighbourhood and safety, the effects of coefficients of marital status, poor health status, labour force status and regional residence are always larger than the larger significant distance observed between two given birth cohorts.

Summary

Results indicate that each generation has distinctively contributed to understanding overall life satisfaction and the different domains observed. More specifically, the cohorts belonging to the Baby Boomers generation and Generation X seem to (negatively) deviate more from the linear trend (particularly late Baby Boomers and early Generation X cohorts) in life satisfaction, but also satisfaction with finances, housing and leisure. In contrast, this very same group positively deviates from the long-run trend in satisfaction with employment opportunities. These birth cohort effects are stronger than some of the control variables included in the analysis. However, family and labour market status have greater effects than cohort of birth on many of the domains studied. Having said that, the cohort effects are significant and non-negligible, particularly in relation to overall life satisfaction, and to a lesser extent also for satisfaction with employment opportunities and housing, which confirm the importance of understanding cohort differences in subjective well-being. Because our results are similar with or without covariates, we conclude that the effects found are not due to these different compositional effects but to the intrinsic specificity and life experiences of birth cohorts.

Conclusions

This paper is a first attempt at disentangling cohort, age, and period effects in life satisfaction and a number of domain satisfactions. Using Australian longitudinal data, we investigate generational differences in overall life satisfaction and eight domain satisfactions. We further compare birth cohort effects to those of other socio-economic characteristics related to subjective well-being. We define four distinct generations, namely the Lucky Generation, Baby Boomers, Generation X, and Generation Y. The results suggest significant differences in subjective well-being across the generations. Consistent with studies on other world regions (e.g. Bardo, 2017; Bardo et al., 2017; Fukuda, 2013; Yang, 2008; Ye & Shu, 2022; Shu & Ye, forthcoming), we find that Baby Boomers are significantly less satisfied with life relative to the generations before and after them. The relatively large number of children born each year for Baby Boomers as compared to earlier and later cohorts may, to a great extent, explain these results. Larger cohort sizes increase the competition to enter schools and the labour market and generate more tensions to accomplish expected economic success and fulfilling family life. Members of bigger cohorts are also more likely to face greater competition related to the labour force, housing, and marriage. They are also more exposed to intense sibling competition, higher income inequality, and fewer education opportunities (Easterlin, 1987). As our results are similar with or without covariates, the unique experiences of these cohorts during childhood and early adulthood can have a lasting impact on their sense of subjective well-being. Given the range of challenges experienced by Baby Boomers, a general inherent cynisicm among individuals in this generation (Yang, 2008; Ye & Shu, 2022) offers at least part of the explanation for why they report lower subjective well-being than other generations.

Younger generations (Generation X but, in particular, Generation Y) are more satisfied with life. Note that Generation Y is growing up in a world significantly different from their Baby Boomer parents: massive migration and cultural pluralism, precarious labour market conditions, widespread consumerism, social media, increased anxiety, greater individualism and increased instability in families. However, the Australian economy was booming at the beginning of the 1980s but went into economic recession in early 1990s to experience a record period of economic growth shortly after. Yet, Australian society, particularly of the 1990s was more affluent and able to accommodate these younger generations offering some good quality of life.

We observe broadly similar patterns when considering other domains such as finances and housing. Interestingly, generational differences in satisfaction with employment opportunities have the opposite pattern, with Baby Boomers and Generation X’s reporting higher satisfaction with employment opportunities as compared to the Lucky Generation and especially those from Generation Y. This pattern can in part be ascribed to greater job instability and increased job competition experienced by Generation Y individuals. When Generation X and Y entered the workforce, unemployment levels were high (ABS, 2006). For example, in 1991, 15% of Generation X and Y men of working age (15–24 years) were unemployed. In contrast, Baby Boomers started entering the workforce in the late 1960s when unemployment levels were very low. By 1971, only 2% of working-age Baby Boomer men (then aged 15–24 years) were unemployed, with similar results for women. Lower levels of unemployment experienced by Lucky Generation women partly reflect their lower levels of female labour force participation compared to younger generations (ABS, 2006).

This study focuses on nonlinear generational effects on overall life satisfaction and several satisfaction domains. Results show that while subjective well-being change does not occur uniformly across these dimensions, its effect remains significant for most of the analysis, highlighting the importance of shared experiences unique to each generation over time in understanding differences in subjective well-being.

Availability of Data

This paper uses unit record data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The HILDA Project was initiated and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS) and is managed by the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research (Melbourne Institute). The findings and views reported in this paper, however, are those of the author and should not be attributed to either DSS or the Melbourne Institute. All data are available to download for users who register with Australian Data Archive. More information can be found at: https://dataverse.ada.edu.au/dataverse/hilda.

Notes

To the best of our knowledge, the APCD approach has not yet been used to examine generational differences in subjective well-being though it has produced reliable estimates in studies on political participation (Chauvel & Smits, 2015), earnings (Chauvel & Schröder, 2014; Kim & Cheung, 2015; Karonen & Niemela, 2020), suicide research (Chauvel et al., 2016), attitudes towards marriage (Yoonjoo Lee, 2019), occupational mismatch (Vera-Toscano & Meroni, 2021a), and family values and religious beliefs (Vera-Toscano & Meroni, 2021b).

It is important to highlight that older individuals represent those who survived up until a given age. Their responses may therefore not be entirely representative of the original overall population born in that year. This caveat may be problematic for the APC model if the probability of surviving up to age t was somehow correlated with the answers to overall satisfaction and their domains.

Also see Vera-Toscano and Meroni (2021b), who investigated generational differences in religious beliefs and family values in Australia, and use a similar underlying dataset and analytical approach.

See Vera-Toscano and Meroni (2021b) for a detailed discussion of the advantages of the APDC approach over alternative approaches.

For more information on the APCD model, see http://www.louischauvel.org/apcdmethodo.pdf.

All APCD models are estimated using the apcd add-on package in Stata.

Similar figures for each of the domain satisfactions are available upon request.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2006). From generation to generation. Available: [Accessed: 9 February 2022] https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/FCB1A3CF0893DAE4CA25754C0013D844/%24File/20700_generation.pdf

Bardo, A. R. (2017). A life course model for a domains-of-life approach to happiness: Evidence from the United States. Advances in Life Course Research, 33, 11–22.

Bardo, A. R., & Yamashita, T. (2014). Validity of domain satisfaction across cohorts in the US. Social Indicators Research, 117, 367–385.

Bardo, A. R., Lynch, S. M., & Land, K. C. (2017). The importance of the Baby Boom cohort and the Great Recession in understanding age, period, and cohort patterns in happiness. Social Psychology and Personality Science, 8(3), 341–350.

Bauer, J. M., Levin, V., Boudet, A. M. M., Nie, P., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2017). Subjective well-being across the lifespan in Europe and Central Asia. Population Ageing, 10, 125–158.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science and Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749.

Chancel, L. (2014). Are younger generations higher carbon emitters than their elders?: Inequalities, generations and CO2 emissions in France and in the USA. Ecological Economics, 100, 195–207.

Chauvel, L. (2011). Age-Period-Cohort with hysteresis APC-H model/A method. (Available at: http://www.louischauvel.org/apchmethodoc.pdf).

Chauvel, L. (2012). APCD: Stata module for estimating age-period-cohort effects with detrended coefficients. Statistical Software Components S457440, Boston College Department of Economics.

Chauvel, L., & Schröder, M. (2014). Generational inequalities and welfare regimes. Social Forces, 92(4), 1259–1283.

Chauvel, L., & Schröder, M. (2015). The impact of cohort membership on disposable incomes in West Germany, France, and the United States. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 298–311.

Chauvel, L., & Smits, F. (2015). The endless baby boomer generation: Cohort differences in participation in political discussions in nine European countries in the period 1976–2008. European Societies, 17(2), 242–278.

Chauvel, L., Leist, A. K. & Ponomarenko, V. (2016). Testing persistence of cohort effects in the epidemiology of suicide: an age-period-cohort hysteresis model. PLoS ONE, 11(7), e0158538.

Daley, J., Wood, D., Weidmann, B., Harrison, C. (2014). The wealth of generations. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/820-wealth-of-generations3.pdf (last accessed 9 February 2022).

de Ree, J., & Alessie, R. (2011). Life satisfaction and age: Dealing with underidentification in age-period-cohort models. Social Science & Medicine, 73, 177–182.

Dries, N., Pepermans, P. & De Kerpel, E. (2008). Exploring four generations’ beliefs about career. Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 23 Iss 8 pp. 907–928.

Easterlin, R. A. (1987). Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal Welfare (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Fienberg, S. E., & Mason, W. M. (1979). Identification and estimation of age-period-cohort models in the analysis of discrete archival data. In K. F. Schuessler (Ed.), Sociological Methodology (pp. 1–67). Josey-Bass.

Fukuda, K. (2013). A happiness study using age-period-cohort framework. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 135–153.

George, L. K. (2010). Still happy after all these years: Research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(3), 331–339.

Glenn, N. D. (2005). Cohort Analysis. Sage.

Harrington, B., van Deusen, F., Fraone, J. S. & Morelock, J. (2015). How millennials navigate their careers: young adult views on work, life and success. Available at: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A72887 (last accessed 9 February 2022).

Holdford, T. R. (1991). Understanding the effects of age, period, and cohort on incidence and mortality rates. Annual Review of Public Health, 12(1), 425–457.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernisation, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51.

Karonen, E., & Niemelä, M. (2020). Life course perspective on economic shocks and income inequality through age-period-cohort analysis: Evidence from Finland. Review of Income and Wealth, 66(2), 287–310.

Kendig, H. (2017). Australian developments in ageing: Issues and history. In K. O’Loughlin, C. Browning, & H. Kendig (Eds.), Ageing in Australia: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 13–27). Springer.

Kim, E. H. W., & Cheung, A. K. L. (2015). Women’s attitudes toward family formation and life stage transitions: A longitudinal study in Korea. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(5), 1074–1090.

Lee, Y. (2019). Cohort differences in changing attitudes toward marriage in South Korea, 1998–2014: An age period-cohort-detrended model. Asian Population Studies, 15(3), 266–281.

Luo, L. (2013). Assessing validity and application scope of the intrinsic estimator approach to the age-period-cohort problem. Demography, 50, 1945–1967.

Luo, L., Hodges, J. S., Winship, C., & Powers, D. (2016). The Sensitivity of the Intrinsic Estimator to Coding Schemes: Comment on Yang, Schulhofer-Wohl, Fu, and Land. American Journal of Sociology, 122, 930–961.

Mason, K. O., Mason, W. M., Winsborough, H. H., & Kenneth, W. P. (1973). Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. American Sociological Review, 38, 242–258.

Mason, W. M. & Wolfinger, N. H. (2001). Cohort analysis. UCLA: California Center for Population Research. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8wc8v8cv.

Rodgers, W. (1982). Trends in reported happiness within demographically defined subgroups, 1957–78. Social Forces, 60(3), 826–842.

Ryder, N. B. (1965). The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. American Sociological Review, 30(6), 843–861.

Settersten, R. A. (2002). Socialization and the life course: New frontiers in theory and research. Advances in Life Course Research, 7, 13–40.

Shu, X., & Ye, Y. Forthcoming. Cohort size, historical times and life chances: The misfortune of children of China’s cultural revolution, in Y. Li and Y. Bian (Eds.), Handbook of Sociology of China. Imperial College Press.

Slack, T., & Jenson, L. (2008). Birth and fortune revisited: A cohort analysis of underemployment, 1974–2004. Population Research and Policy Review, 27(6), 729–749.

Summerfield, M., Bright, S., Hahn, M., La, N., Macalalad, N., Watson, N., Wilkins, R., & Wooden, M. (2019). HILDA User Manual – Release 18. Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne.

Tang, Z. (2014). They are richer but are they happier? Subjective well-being of Chinese Citizens across the reform era. Social Indicators Research, 117, 145–164.

Vera-Toscano, E., & Meroni, E. C. (2021a). An age-period-cohort approach to the incidence and evolution of overeducation and skills mismatch. Social Indicators Research, 153, 711–740.

Vera-Toscano, E., & Meroni, E. C. (2021b). An age-period-cohort approach to disentangling generational differences in family values and religious beliefs: Understanding the modern Australian family today. Demographic Research, 45, 653–692.

Yang, Y. (2008). Social inequalities in happiness in the United States, 1972 to 2004: An age-period-cohort analysis. American Sociological Review, 73, 204–226.

Ye, Y., & Shu, X. (2022). Lonely in a crowd: Cohort size and happiness in the United Kingdom. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00495-x

Zhang, T. H., Hu, J., & Zhang, X. (2020). Disparities in subjective wellbeing: Political status, urban-rural divide, and cohort dynamics in China. Chinese Sociological Review, 52(1), 56–83.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. This research was partly supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

The research complies with the required ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All authors provided consent for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Botha, F., Vera-Toscano, E. Generational Differences in Subjective Well-Being in Australia. Applied Research Quality Life 17, 2903–2932 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10047-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-022-10047-x