Abstract

Objectives

To experimentally examine public perceptions of police canine units.

Methods

As part of the between-subjects paradigm, participants were randomly assigned to view and rate an image of a police officer either with a police dog (i.e., as a police canine unit) or alone on eight dimensions: aggression, approachability, fairness, friendliness, intimidation, professionalism, respectfulness, and trustworthiness.

Results

The analyses reveal that the officer was perceived more negatively when presented with a police dog than when presented alone.

Conclusions

Police dogs play a multifaceted role in policing, including in crime control and public relations. In addition to their many functions, police canine units can also elicit many perceptual effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Police canine units play an arguably salient role in the delivery of police services. Such salience is in part due to the many utilities of police dogs, including in crime control and public relations. Although their range of utilities may be described as a benefit by some, their conflicting functions could also create a potential paradox for public perceptions of these units. The question of how these units are perceived in the context of trait ascriptions remains unanswered. To contribute to this literature, we employ a rigorously controlled between-subjects design to experimentally examine the perceptual effects of police canine units among a sample of adults. Our analyses reveal that an officer is perceived more negatively when presented with a police dog (i.e., as a police canine unit) than when presented alone. Considering the prevalence of police canine units across the policing landscape, our research provides important implications for both scholars and practitioners.

Background

Specialized police units

The advent of police specialty units, one of which are police canine units,Footnote 1 coincided with the movement to professionalize policing. Although police organizations first concentrated on creating specialized units for investigational purposes (Gaub et al., 2021; White, 2007), the bureaucratization of police organizations later led to the development of a range of specialty units designed to address specific crime problems and phenomena (Byfield, 2019; Gaub et al., 2020; Kelling & Moore, 1988). Broadly speaking, police specialty units can now be divided into three categories (Gaub et al., 2020, 2021). First are units which rely on alternative patrol methods, such as bike, marine, or snowmobile patrols. These units typically conduct general patrol duties in defined geographic areas characterized by terrain or other features that make standard vehicle patrol difficult. Second are units which are responsible for specific crime-types that are usually investigations-based (e.g., drug or gang units). Third, and finally, are units which use unique tactics that are otherwise not accessible to general patrol officers, like special weapons and tactics units. Some specialized units can also fall into more than one category, such as search and rescue units, traffic units, and police canine units, the last of which we explore in depth as part of our article.

Police canine units

The use of dogs in policing is deeply embedded in the institution’s history. In the USA, slave patrols routinely used dogs to track runaway slaves, and they have long been used in the context of controlling crowds, particularly racialized groups (e.g., see Byfield, 2019; Spruill, 2016; The Marshall Project, 2021). Despite this history, however, limited scholarly literature has examined police canine units to date.

Of such literature, a small number of studies have evaluated police dogs within the search and rescue context, having focused largely on their health and wellness (Alvarez & Hunt, 2005; Slensky et al., 2004) or deployment tactics (Ferworn et al., 2008; Godfrey-Smith, 2004). Other studies have focused more specifically on hearing loss among canine officers (Malowski & Steiger, 2020) and obedience training among police dogs (Alexander et al., 2011). Related to use-of-force, three studies have focused on police dog bites in large police agencies, finding that the percentage of suspect apprehensions that result in dog bites ranged from 14% (Hickey & Hoffman, 2003) to between 35% and 45% (Campbell et al., 1998) and that “bark and hold” trained dogs bite a greater proportion of suspects than do “bite and hold” trained dogs (Mesloh, 2006). Two studies have also addressed officer perceptions of service dogs. First, Quick and Piza (2021) found that exposure to service dogs significantly increased officers’ perceived organizational support for wellness programs involving police dogs; and, second, Curley et al. (2021) found that first responder participants with more favorable attitudes toward dogs were generally more receptive to the idea of service dogs in the workplace. Finally, Wolf et al. (2010) found that criminal justice knowledge (including in relation to police dogs) impacted university students’ perceptions of police dogs’ effectiveness in crime control on campus.

Now, as introduced above, some specialty units may be classified into more than one category. One such unit of this nature are police canine units, which can be utilized in many different kinds of situations due to the versatility of police dogs. For example, police dogs are sometimes used as compliance tools and agents of force that search, track, bite, and apprehend people as well as detect narcotics, firearms, and explosives (Campbell et al., 1998; Hickey & Hoffman, 2003; Mesloh, 2006). This “crime fighting” utility appears to associate police dogs closely with their sworn officer counterparts. Consistent with this logic, police agencies often conduct “swearing-in ceremonies” for their police dogs and provide them with badges (e.g., see Walby et al., 2018). Police dogs killed in the line of duty are also included on the Officer Down Memorial Page (ODMP, 2022). On the other hand, police dogs are sometimes used to help foster public relations, such as through school presentations, police calendars, and “name the puppy” contests (Holliday, 2020; RCMP, 2022; Walby et al., 2018). On its face, these two utilities appear to be at odds with one another. Capitalizing on the popularity of dogs as pets may foster public relations, yet could create a potential perceptual paradox when the same police dogs used in public relations settings (e.g., engaging with children at community functions) are also used in more traditional crime-fighting situations (e.g., biting a suspect that results in serious injuries). Indeed, it is plausible—perhaps even probable—that an animal otherwise popular in a domestic context may be perceived negatively when presented in a policing context. Experimentally unpacking this paradox comprises the focus of our work.

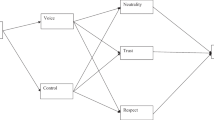

The use of experiments to examine perceptions of police

While literature on police dogs has remained scant, prior research has examined similar perceptual conundrums in a policing context via the use of experimental paradigms. For example, Simpson’s (2017, 2020, 2021) research found that subtle manipulations to police officer appearance (e.g., uniforms, accoutrements, facial expressions) impacted public perceptions of officers. In similar experimental work, Yesberg et al. (2021) observed that British participants perceived officers more negatively when they were armed versus unarmed. And, more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, Sandrin and Simpson (2022) found that an officer’s use of personal protective equipment (PPE) positively impacted participants’ perceptions of procedural justice (for other related experiments involving perceptions of police, see Blaskovits et al. (2022) and Thielgen et al. (2020)). Similar to such research, we thus utilize an experimental design as part of our study to explore the perceptual effects of police canine units.

Data and methods

Participants

We recruited 201 participants via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (hereinafter referred to as “MTurk”) for our research. MTurk is a popular sampling platform that has been used in related research (e.g., Nix et al., 2021; Sandrin & Simpson, 2022; Simpson, 2021) given its ability to provide diverse and representative samples quickly, conveniently, and at low costs (e.g., Casler et al., 2013; Mortensen & Hughes, 2018; Paolacci et al., 2010). All participants recruited for the study were (1) registered on MTurk, (2) residing in Canada or the USA, (3) at least 18 years of age, and (4) able to speak, read, and write English.

Consistent with prior research, we were able to recruit a diverse sample using this platform. As shown in Table 1, participants ranged in age from 18 to 72 (M = 36, SD = 10.63) and self-identified as Asian (11%), Black (5%), White (75%), or other (9%). Most participants identified as being married (57%) and having a Bachelor’s degree (58%). Nearly half of the participants perceived that their income was about average compared to other people living in their region.

Procedure

Upon enrollment in the study, participants were advised that the study sought to investigate attitudes about dogs in the workplace. Participants were further informed that as part of the study, they would rate images of dogs and people in workplace settings. The use of generic terms such as “dogs” and “people” in lieu of specific terms such as “police dogs” and “police officers” was necessary to minimize potential demand characteristics that could have otherwise biased participants’ perceptions of police. Following completion of the task, participants were provided with a debriefing sheet which provided information about the study.

As part of the online perception task, participants rated seven different images of dogs and/or people on eight dependent variables (as described below).Footnote 2 Unbeknownst to participants, we embedded the experimental portion of our study in the first image presented during the task. Here, participants were randomly assigned to rate one of two images: a police officer and police dog (experimental; n = 96) or the same officer but without the police dog (control; n = 105). The experimental image depicted a police officer standing on a grass field in a neutral posture with their hands by their side and the police dog sitting next to them (i.e., as a police canine unit). The officer was wearing a standard-issued patrol uniform, including an operational duty belt, navy blue long-sleeve collared shirt, navy blue pants, and patrol boots. The police dog, which we operationalized as a German Shepherd (given their frequent use in police canine units), was seated next to the officer and outfitted in a K9-issued harness with the word, “POLICE,” on its side. We digitally removed all identifiers of the officer (including their organizational affiliation) for the purposes of our research. The control image was the same as the experimental image, except we digitally removed the police dog using image editing software (i.e., we replaced the void space with grass). No other elements were digitally modified, and thus all else was held constant between the experimental and control image.

After rating either the experimental or control image (depending upon condition), all participants then rated the same set of distractor images. These images included (1) a person and non-police dog,Footnote 3 (2) a medical doctor and non-police dog, (3) an elderly person and non-police dog, (4) a person alone, (5) a non-police dog alone, and (6) a police dogFootnote 4 alone. The order of the distractor images was randomized across participants in order to control for potential order effects.

Dependent variables

Participants used 5-point Likert scales (ranging from “strongly disagree” [− 2] to “strongly agree” [2]) to rate their level of agreement about the person and/or dog in each image on eight dependent variables: (1) aggression, (2) approachability, (3) fairness, (4) friendliness, (5) intimidation, (6) professionalism, (7) respectfulness, and (8) trustworthiness. We adopted these dependent variables predominately from paradigms used in related research involving public perceptions of police (e.g., Blaskovits et al., 2022; Simpson, 2017, 2020, 2021; Thielgen et al., 2020; Yesberg et al., 2021), with some modifications to accommodate for the nuance of our experimental manipulation, including its focus on police dogs.

Results and discussion

We begin our analyses by employing a series of independent samples t-tests to assess differences in participants’ perceptions of the officer when presented with a police dog (experimental) versus alone (control). As shown in Table 2, our analyses revealed a number of significant findings. First, the officer and police dog duo tended to elicit a negative interpersonal effect: participants perceived the duo to be significantly less approachable (t(183) = 4.147, difference = 0.629, p < 0.001) and friendly (t(179) = 3.212, difference = 0.429, p < 0.01) when compared to the officer alone. Second, the officer and police dog duo also tended to elicit a threatening effect: participants perceived the duo to be significantly more aggressive (t(199) = -3.239, difference = 0.510, p < 0.01) and intimidating (t(199) = -2.217, difference = 0.340, p < 0.05) when compared to the officer alone.

These results suggest that the dependent variables most tangible in the context of our experimental manipulation were most strongly affected by such manipulation. Consistent with this logic, the traits reflected in the dependent variables that did not vary significantly between groups appear to be further removed from the manipulation and thus likely harder for participants to render perceptual judgment. For example, it may have been easier for participants to derive judgments about aggression (which was found to differ significantly between groups) in the context of the manipulation than to derive judgments about professionalism (which was not found to differ significantly between groups). Nevertheless, the findings from our analyses suggest that the officer was perceived more negatively when presented with a police dog than when presented alone.

Even in light of these observed differences, though, it is still possible that confounding factors may have affected our findings. In order to test for possible confounders, we thus employed a series of ancillary analyses to examine whether our groups varied in their perceptions of the same distractor images. As part of these assessments, we compared the two groups in search of differences in ratings of the police dog alone (Distractor Image 6) as well as the collapsed means of the remaining distractor images (Distractor Images 1–5) for each of the eight dependent variables. The two sets of independent samples t-tests revealed only one significant finding: participants assigned to the control group perceived the police dog alone to be significantly more respectful (t(185) = 2.259, difference = 0.299, p < 0.05) than participants assigned to the experimental group. The general lack of significant findings stemming from these ancillary analyses therefore provide further evidence to support our claim that it was the difference between the experimental and control image that affected participants’ perceptions as opposed to other more extraneous factors.

Implications

These findings exhibit important implications for scholars and practitioners. By employing a rigorously controlled experimental paradigm, we were able to test questions of a perceptual nature in the context of police canine units. Given that the officer and police dog duo were perceived more negatively than the same officer alone, it appears that the police dog may be driving negative perceptions of the former. This conclusion is further corroborated by the results of our ancillary analyses, which helped to rule out many extraneous explanations. In drawing inferences from the findings, a key consideration may involve police dogs’ multifaceted roles as both agents of force and public relations tools (Campbell et al., 1998; Hickey & Hoffman, 2003; Mesloh, 2006; RCMP, 2022; Walby et al., 2018). Although the manipulation in our experimental paradigm depicted the police dog in a neutral position, participants may have internalized the more tactical and crime-fighting elements of police dogs when paired with officers, which may then have impacted their perceptions. And, indeed, the specific dependent variables that differed significantly between groups appear to be consistent with such logic.

While police dogs may be perceived by some to serve in merely an ancillary capacity within the policing nexus (consistent with their speciality unit classification), police dogs have and continue to generate considerable public attention, including in their interactions with the public.Footnote 5 Given that public interactions with police dogs can involve a host of possible situations (ranging from friendly encounters [low salience] to severe dog bites [high salience]), the best practices of police dogs in the context of their utilities warrants attention. If police agencies are justifying their use of police dogs in certain contexts solely on their alleged perceptual benefits (as may be the case with respect to public relations), then the findings from the present research should cause concern. Even though we could not account for context, the police dog and officer duo (at least during an unceremonious observation as mirrored in our paradigm) elicited many negative perceptual effects. While police dogs are still “dogs” that are otherwise popular as human pets, they may be less effective in fostering public relations than sometimes argued by practitioners and used in practice (e.g., Holliday, 2020; Walby et al., 2018).

With that being said, the perceptual effects that police canine units elicit may only be as relevant to police practitioners as the situation in which they are utilized. For example, if police dogs are utilized in the context of crime control, the importance of dealing with the incident at hand likely supersedes the police’s concern about the general perceptions they may elicit. Conversely, when police dogs are utilized for the sole intent of fostering public relations, perceptions become much more important. Evidently, the diversity of police dogs’ many functions is complicated to untangle, and research must continue to assess phenomena related to police dogs as it emerges in order to further the development of an evidence base for policy and practice.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, the present research still exhibits several limitations. First, our laboratory-style framework was unable to provide context regarding participants’ perceptions, including why some dependent variables exhibited significant differences whereas others did not. Relatedly, although we employed random assignment to conditions to control for variation at the group level, we recognize that some demographic variation may still exist. In this vein, future research should employ qualitative methods to gain greater breadth and depth of understanding regarding public perceptions of police canine units.

Second, although the present research contributes to the limited literature on police canine units, there are still many questions that require investigation. For example, while our paradigm depicted an officer and police dog in a neutral stance, showcasing police canine units in different capacities may elicit different perceptions (e.g., when actively searching for persons of interest as opposed to locating explosives as opposed to posing for photographs). It also remains unclear how police dogs are perceived in the grand scheme of animals in the workplace (e.g., relative to comfort and therapy dogs used in other workplace settings, such as courtrooms). Researchers working within this domain should continue to explore questions related to police dogs as well as the role of animals within the criminal justice system/workplace more broadly.

Conclusion

Police canine units continue to play a prominent role in policing as a result of their involvement in crime control and public relations. As part of our research, we sought to experimentally test the effects of these units on public perceptions of police. Our findings revealed that police dogs can elicit negative perceptual effects when presented alongside an officer as part of a police canine unit. In an era where policing continues to be examined scrupulously, police agencies must ensure that they carefully consider their use of police dogs in light of the research regarding their functions and effects.

Notes

These units are sometimes described stylistically as “K9 units” or otherwise referred to as “police dog units.”

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board at the university where the experiment was conducted.

Aside from the final distractor image of the police dog alone, we deliberately featured dog breeds not generally associated with the police in our distractor images, such as Golden Retrievers.

Note that the police dog featured in this distractor image (also a German Shepherd) is different from the police dog featured in the experimental image.

As one example, the recent stabbing death of a police dog resulted in an outpour of tributes, including from the Commanding Officer of the police in the jurisdiction where the incident took place (Taylor, 2021).

References

Alexander, M. B., Friend, T., & Haug, L. (2011). Obedience training effects on search dog performance. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 132(3–4), 152–159.

Alvarez, J., & Hunt, M. (2005). Risk and resilience in canine search and rescue handlers after 9/11. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 497–505.

Blaskovits, B., Bennell, C., Baldwin, S., Ewanation, L., Brown, A., & Korva, N. (2022). The thin blue line between cop and soldier: Examining public perceptions of the militarized appearance of police. Police Practice and Research, 23(2), 212–235.

Byfield, N. P. (2019). Race science and surveillance: Police as the new race scientists. Social Identities, 25(1), 91–106.

Campbell, A., Berk, R. A., & Fyfe, J. J. (1998). The deployment of violence: The Los Angeles Police Department’s use of dogs. Evaluation Review, 22(4), 535–561.

Casler, K., Bickel, L., & Hackett, E. (2013). Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2156–2160.

Curley, T., Campbell, M. A., Doyle, J. N., & Freeze, S. M. (2021). First responders’ perceptions of the presence of support canines in the workplace. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09477-4

Ferworn, A., Ostrom, D., Barnum, K., Dallaire, M., Harkness, D., & Dolderman, M. (2008). Canine remote deployment system for urban search and rescue. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 5(1), 1–8.

Gaub, J. E., Todak, N., & White, M. D. (2020). One size doesn’t fit all: The deployment of police body-worn cameras to specialty units. International Criminal Justice Review, 30(2), 136–155.

Gaub, J. E., Todak, N., & White, M. D. (2021). The distribution of police use of force across patrol and specialty units: A case study in BWC impact. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17(4), 545–561.

Godfrey-Smith, D. (2004). Effective use of dogs in search management. Search & Rescue Dogs of Tasmania. https://webarchive.libraries.tas.gov.au/20120308024931/http://www.tco.asn.au/uploaded/48/686-686-171119_08effectiveuseofdogsinsea.pdf

Hickey, E. R., & Hoffman, P. B. (2003). To bite or not to bite: Canine apprehensions in a large, suburban police department. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31(2), 147–154.

Holliday, I. (2020). VPD releases 2021 police dog calendar. CTV News. https://bc.ctvnews.ca/vpd-releases-2021-police-dog-calendar-1.5158745

Kelling, G. L., & Moore, M. H. (1988). The evolving strategy of policing. US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice. https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/evolving-strategy-policing.

Malowski, K. S., & Steiger, J. (2020). Hearing loss in police K9 handlers and non-K9 handlers. International Journal of Audiology, 59(2), 109–116.

Mesloh, C. (2006). Barks or bites? The impact of training on police canine force outcomes. Police Practice and Research, 7(4), 323–335.

Mortensen, K., & Hughes, T. L. (2018). Comparing Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform to conventional data collection methods in the health and medical research literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(4), 533–538.

Nix, J., Ivanov, S., & Pickett, J. T. (2021). What does the public want police to do during pandemics? A national experiment. Criminology & Public Policy, 20(3), 545–571.

Officer Down Memorial Page (ODMP). (2022). Fallen K9s. https://www.odmp.org/k9

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgement and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419.

Quick, K. M., & Piza, E. L. (2021). Police officers’ best friend?: An exploratory analysis of the effect of service dogs on perceived organizational support in policing. The Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258x211044711

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). (2022). “Name the puppy” 2022. https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/news/2022/name-the-puppy

Sandrin, R., & Simpson, R. (2022). Public assessments of police during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of procedural justice and personal protective equipment. Policing: An International Journal, 45(1), 154–168.

Simpson, R. (2017). The Police Officer Perception Project (POPP): An experimental evaluation of factors that impact perceptions of the police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(3), 393–415.

Simpson, R. (2021). When police smile: A two sample test of the effects of facial expressions on perceptions of police. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(2), 170–182.

Simpson, R. (2020). Officer appearance and perceptions of police: Accoutrements as signals of intent. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(1), 243–257.

Slensky, K. A., Drobatz, K. J., Downend, A. B., & Otto, C. M. (2004). Deployment morbidity among search-and-rescue dogs used after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 225(6), 868–873.

Spruill, L. H. (2016). Slave patrols, “packs of Negro dogs” and policing Black communities. Phylon, 53(1), 42–66.

Taylor, A. (2021). Memorial for Campbell River police dog killed in line of duty grows. Castlegar News. https://www.castlegarnews.com/community/memorial-for-campbell-river-police-dog-killed-in-line-of-duty-grows/

The Marshall Project. (2021). Mauled: When police dogs are weapons. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/10/15/mauled-when-police-dogs-are-weapons

Thielgen, M. M., Schade, S., & Rohr, J. (2020). How criminal offenders perceive police officers’ appearance: Effects of uniforms and tattoos on inmates’ attitudes. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 20(3), 214–240.

Walby, K., Luscombe, A., & Lippert, R. K. (2018). Going to the dogs? Police, donations, and K9s. Policing: An International Journal, 41(6), 798–812.

White, M. D. (2007). Current issues and controversies in policing. Allyn & Bacon.

Wolf, R., Mesloh, C., & Henych, M. (2010). Fighting campus crime: Perceptions of police canines at a metropolitan university. Critical Issues in Justice and Politics, 3(1), 1–18.

Yesberg, J. A., Bradford, B., & Dawson, P. (2021). An experimental study of responses to armed police in Great Britain. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17(1), 1–13.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sandrin, R., Simpson, R. & Gaub, J.E. An experimental examination of the perceptual paradox surrounding police canine units. J Exp Criminol 19, 1021–1031 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09516-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-022-09516-y