Abstract

We present an empirical model aimed at testing the relative income hypothesis and the effect of deprivation relative to mean income on subjective well-being. The main concern is to deal with subjective panel data in an ordered response model where error homoskedasticity is not assumed. A heteroskedastic pooled panel ordered probit model with unobserved individual-specific effects is applied to micro-data available in the British Household Panel Survey for 1996–2007. In this framework, absolute income impacts negatively on both completely satisfied and dissatisfied individuals, while relative income affects positively the most satisfied ones. Such an effect is asymmetric, impacting more severely on the relatively poor in the reference group. We argue that our results buttress the validity of the relative income hypothesis as an explanation of the happiness paradox.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The heteroskedastic ordered probit is also known as heterogeneous choice/ location-scale ordinal probit. We coined the term heteroskedastic pooled panel ordered probit for synthesizing the features of the model we use: an ordered probit, pooled, but still allowing more robustness than cross-sectional analyses (panel), and controlling for potential heteroskedasticity (heteroskedastic).

The deprivation measure consists of a multiplicative term which includes a dummy and relative income. The dummy takes on the unity when personal income is below the reference one.

Life satisfaction is thought of as being a good proxy for welfare, a more general concept the researchers actually focus on. Also, life satisfaction is presumed to be ordinally comparable between individuals. Loosely speaking, we can recognize if any two individuals are better off, worse off or equally well off in terms of welfare. This implies that happiness is a concept perceived much the same way. Being life satisfaction a monotonic transformation of welfare, we are able to discern happier individuals from less happy ones.

Lastly, a cardinal comparability of life satisfaction (preferences) between individuals is assumed to be possible. This means assuming that the difference between any two consecutive scores in the satisfaction scale is the same regardless of the rank. Such a hypothesis is not very widespread for its perversity to the standard microeconomic theory. Indeed, a controversy on happiness (or utility) cardinal measurability exists in this literature. In these regards, Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004) produce evidence that the assumption of cardinality of life satisfaction scores has a negligible impact on empirical results. Indeed, we argue that such an assumption is closely related to the econometric method used for the empirical analysis, and that when ordinal discrete models are used, cardinality is not a major concern.

Henceforth in this subsection we disregard subscripts for expositional neatness; the specification refers to individual n at period t.

In fixed effects models, the number of parameters increases with the number of individuals, because we estimate them as unknown parameters. When n becomes large, but T is finite, the maximum likelihood estimator is inconsistent.

The number of waves an individual is surveyed may change due to several reasons, such as death, immigration and attrition or because new individuals become part of the household.

We drop all the non-full interviews. From Wave 7 (1997) there is oversampling of low income people for comparability with the European Community Household Panel. Moreover, many more observations have been sampled for Scotland and Wales. In order to maintain comparability with previous waves and random sampling, we keep only observations belonging to the original sample.

Socrates was the first philosopher using this term; Aristoteles and Plato contributed to develop the concept in relationship with the moral and political disciplines.

Source UK National Statistics (http://www.statistics.gov.uk/hub/index.html).

A person whose income is 20,000 GBP, and confronts herself with a reference income of 30,000 GBP, experiences the same relative deprivation of an individual having 90,000 GBP per year and a comparison income of 100,000 GBP.

For instance, men and women have different sensibility and ambitions, as it is well-known.

Percentage computed from the sum of densities relative to responses between 5 and 7.

Marginal partial effects computed as in (3).

Marginal partial effects computed for HPPOP as in (4).

References

Alesina, A., Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2004). Inequality and happiness: Are europeans and americans different. Journal of Public Economics, 88(910), 2009–2042.

Alvarez, R., & Brehm, J. (1997). Are Americans ambivalent towards racial policies. American Journal of Political Science, 41, 345–374.

Alvarez, R., & Brehm J. (1998). Speaking in two voices: American equivocation about the internal revenue service. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 418–452.

Alvarez, R., & Brehm, J. (2002). Hard choices, easy answers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

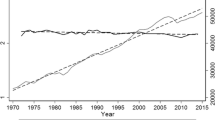

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2001). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. TheWarwick Economics Research Paper Series (TWERPS) 616, University of Warwick, Department of Economics.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald A. (2004a). Money, sex and happiness: An empirical study. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106(3), 393–415.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (2004b). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Boes, S., Staub, K., & Winkelmann, R. (2010). Relative status and satisfaction. Economics Letters, 109, 168–170.

Boes, S., & Winkelmann, R. (2006). Ordered response models. Advances in Statistical Analysis, 90(1), 167–181.

Busch, M., & Reinhardt, R. (1999). Industrial location and protection: The political and economic geography of U.S. nontariff barriers. American Journal of Political Science, 43, 1028–1050.

Clark, A., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(1), 95–144.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659.

Dietz, R. D. (2002). The estimation of neighborhood effects in the social sciences: An interdisciplinary approach. Social Science Research, 31, 539–575.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 21(1), 94–122.

Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, savings and the theory of consumer behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dynan, K., & Ravina, E. (2007). Increasing income inequality, external habits and self-reported happiness. American Economic Review, 97(2), 226–231.

Easterlin R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramowitz. New York and London: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 27, 35–48.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Economic Journal 101, 465–484.

Easterlin, R. A. (2003). Explaining happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100, 11176–11183.

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A. (2005). Income and well-being: An empirical analysis of the comparison income effect. Journal of Public Economics, 89(5–6), 997–1019.

Ferrer-i Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Firebaugh, G., & Tach, L. (2000). Income and happiness in the United States. Technical report, Harvard University.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (1999). Measuring preferences by subjective well-being. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE), 155(4), 755–778.

Frey, B., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. Economic Journal, 110(466), 918–938.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J., & Shields, M. (2004a). Investigating the patterns and determinants of life satisfaction in Germany following reunification. Journal of Human Resources 39(3), 649–674.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J., & Shields, M. (2004b). Money does matter! Evidence from increasing real income and life satisfaction in East Germany following reunification. American Economic Review, 94(3), 730–740.

Gabel, M. (1998). Economic integration and mass politics: Market liberalization and public attitudes in the European Union. American Journal of Political Science, 42, 936–953.

Graham, C. (2008). The economics of happiness. Houndmills, England: Macmillan. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.

Gravelle, H., & Sutton R. (2009). Income, relative income, and self-reported health in Britain 1979–2000. Health Economics, 18, 125–145.

Hagerty, M., & Veenhoven R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited—Growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64(1), 1–27.

Headey, B., Muffels, R., & Wooden, M. (2008). Money does not buy happiness: Or does it? A reassessment based on the combined effects of wealth, income and consumption. Social Indicators Research, 87(1), 65–82.

Hsiao, C. (1986). Analysis of panel data. Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press. Econometric Society Monograph.

Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (2003). Well-Being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Keele, L., & Park, D. (2006). Ambivalent about ambivalence: A re-examination of heteroskedastic probit models. Technical report.

Krutz, G. (2005). Issues and institutions: Winnowing in the US congress. American Journal of Political Science, 49, 436–447.

Lee, T. (2002). Mobilizing public opinion: Black insurgency and racial attitudes in the civil rights era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lelkes, O. (2006). Knowing what is good for you: Empirical analysis of personal preferences and the “ objective good” . The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(2), 285–307.

Luttmer, E. (2005). Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 963–1002.

Maddala, G. (1983). Limited dependent and qualitative variables in econometrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McBride, M. (1978). Relative-income effects on subjective well-being in the cross-section. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 45, 251–278.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica, 46, 69–85.

Oswald, A. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. Economic Journal, 107, 1815–1831.

Sacks, D., Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2010). Subjective well-being, income, economic development and growth. NBER Working Papers 16441, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

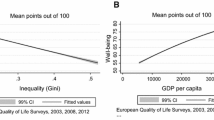

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 39(1), 1–102.

Williams, R. (2010). Fitting heterogeneous choice models with oglm. Stata Journal, 10(4), 540–567.

Williams, R. (2011). Oglm: Stata module to estimate ordinal generalized linear models. SSC STATA Modules.

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mette Ejrnæs, Lars Peter Østerdal, Marcos Vera Hernandez, Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell, and Emiliano Santoro for their invaluable discussions. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Dataset Features and Statistical Package

Appendix: Dataset Features and Statistical Package

Quoting the official BHPS web site “The British Household Panel Survey” began in 1991 and is a multi-purpose study whose unique value resides in the fact that:

-

it follows the same representative sample of individuals—the panel—over a period of years;

-

it is household-based, interviewing every adult member of sampled households;

-

it contains sufficient cases for meaningful analysis of certain groups such as the elderly or lone parent families.

The wave 1 panel consists of some 5,500 households and 10,300 individuals drawn from 250 areas of Great Britain” . From Wave7 (1997), there is oversampling of low income people for comparability with ECPH. “ Moreover, many more observations have been sampled for Scotland and Wales. Additional samples of 1,500 households in each of Scotland and Wales were added to the main sample in Wave9 (1999), and in 2001 a sample of 2,000 households was added in Northern Ireland, making the panel suitable for UK-wide research”.

Data in each wave are organized in different macro-groups: INDSAMP includes all sampled individuals (either respondents or not), INDALL is an individual level record for all members of the household, corresponding to the household grid, INDRESP includes responding individuals only. The same applies to household-specific data, collected into HHSSAMP, HHSAMP and HHRESP. Hence, when extracting the individual interview outcome (IVFIO) from INDSAMP/HHSAMP, we are taking more observations than those that we have in INDRESP/HHRESP. They are dropped when drop** according to IVFIO (we drop all the observations where the interview outcome was not 1, i.e. all the non-full interviews). Also, in order to maintain comparability with previous waves and random sampling, we keep only observations belonging to the original sample (MEMORIG=1 for INDRESP and HHORIG=1 for HHRESP), disregarding the data added from 1997, 1999 and 2001 mentioned before.

Here follows a list of BHPS codes for the raw variables used in our analysis, in alphabetical order:

Raw Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|

age | Age from birth | Biographic | Continuos |

fihhyl | Annual household labor income | Derived | Continuous |

fihhynl | Annual household non-labor income | Derived | Continuous |

hgemp | In paid employment—household grid | Self-reported | Binary |

hllte | Health no indrance daily activities | Self-reported | Binary |

hlstat | Health over last 12 months | Self-reported | 1–5 ordered |

lfsato | Satisfaction with life overall | Self-reported | 1–7 ordered |

mastat | Marital status | Biographic | 5 different stati |

nchild | Number of own children in household | Biographic | Continuous |

race | Ethnicity | Biographic | 5 different races |

region | Region / metropolitan area | Biographic | 18 UK sub-regions |

sex | Gender | Biographic | |

By means of STATA, the PPOP model has been estimated using the standard command oprobit . For the HPPOP model, instead, we have made use of a STATA module by Williams (2010, 2011), known as oglm .

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Distante, R. Subjective Well-Being, Income and Relative Concerns in the UK. Soc Indic Res 113, 81–105 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0083-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0083-z