Abstract

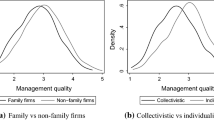

Motivated by a lack of consensus in the current literature, the objective of this paper is to reveal whether family firms are more or less productive than non-family firms. As a first step, this paper links family business research to the theoretical notion that family involvement has an effect on the factors of production from a productivity standpoint. Second, by using a Cobb–Douglas framework, we provide empirical evidence that family labour and capital indeed yield diverse output contributions compared with their non-family counterparts. In particular, family labour output contributions are significantly higher, and family capital output contributions significantly lower. Interestingly, differences in total factor productivity between family and non-family firms disappear when we allow for heterogeneous output contributions of family production inputs. These findings imply that the assumption of homogeneous labour and capital between family and non-family firms is inappropriate when estimating the production function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Burns and Whitehouse (1996) report that 85% of businesses in the European Union and 90% of businesses in the United States are family controlled. It is also generally recognized that family businesses are critical to entrepreneurship and socioeconomic development and industrialization in unstable, low income, or transitional economies.

Handler (1994) describes the issue of succession as the most important issue that all family firms face; Chua et al. (2003) found that succession is the number one concern of family firms; and Ward (1987) goes so far as to define all family firms specifically as those that will be “passed on for the family’s next generation to manage and control”.

Some studies listed in Table 1 have concentrated on the partial productivity of family firms in that they focus on the ratio of output to a single input factor, usually labour; however partial analysis only provides a general indication of total factor productivity, because it fails to consider tradeoffs between other input factors.

One notable exception is Martikainen et al. (2009) who tested whether factor elasticities (namely the coefficient estimates for both labour and capital) are invariant across both family and non-family firms. They found that, for their sample of 159 manufacturing firms, there is no such variance in elasticity, and proceeded to test differences in productivity using fixed factor elasticities for both family and non-family firms.

According to Gómez-Mejía et al.(2007), “the socioemotional wealth of family firms comes in a variety of related forms, including the ability to exercise authority… the perpetuation of family values through the business… the preservation of the family dynasty… the conservation of the family firm's social capital… the fulfilment of family obligations based on blood ties rather than on strict criteria of competence… and the opportunity to be altruistic to family members. Losing this socioemotional wealth implies lost intimacy, reduced status, and failure to meet the family's expectations”.

If both principal and agent have the same interests, there is no conflict of interest and no “agency problem” (Berle and Means 1932; Ross 1973); thus by virtue of their intra-familial altruistic element, family firms should be exempt from agency problems (Becker 1974; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Parsons et al. 1986; Eisenhardt 1989; Daily and Dollinger 1992). However, more recent investigations have looked into other types of agency problem that may be specific to family firms (Morck and Yeung 2003; Chrisman et al. 2004).

In their analysis, Cobb and Douglas (1928) investigate production in manufacturing firms and, as a result, land is excluded as a factor of production.

In the log transformed Cobb–Douglas production function, the value of the constant coefficient is independent of labour and capital. This assumption has been made to ignore the qualitative effects of any force for which there is no quantitative data. The coefficient is thus made a “catch-all” for the effects of such forces (Cobb and Douglas 1928).

An important consideration is the simultaneous equation bias that may arise when specifying management variables in the production function (Hoch 1958). In the case of the added family firm variable, we may find that productivity depends on whether the firm is a family firm and whether the firm is a family firm depends on productivity. For example, whether a firm remains in the control, management, and ownership of the family may be endogenously determined by the performance of the firm. Poorly performing family firms may resort to outside management as a potential remedy and, on the other hand, families may be less inclined to relinquish ownership, management, or control of a highly performing firm (Demsetz and Lehn 1985; Demsetz and Villalonga 2001). If correlations between the error term and independent variables exist, coefficient estimates of Eqs. 1 and 2 may end up being biassed and therefore inconsistent, because it is assumed that independent variables are in fact independent or exogenous.

The BLS samples were drawn from the ABS Business Register, with 8745 business units being selected for inclusion in the 1994–1995 survey. For the 1995–1996 survey, 4,948 of the original selections for the 1994–1995 survey were selected, and this was supplemented by 572 new business units added to the ABS Business Register during 1995–1996. The sample for the 1996–1997 survey included 4,541 businesses which were previously sampled, and an additional sample of 529 new businesses from the 1995–1996 interrogation of the Business Register, and 551 new businesses from the 1996–1997 interrogation of the Business Register.

The equivalent ratio is simply calculated as average part-time hours per week divided by average full-time hours per week for all non-managerial employees. This information is from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ “Employee Earnings and Hours, Australia” report as of 1998 and from the previously known “Earnings and Hours of Employees, Distribution and Composition, Australia” report.

Of all family firms responding to question 2, 34.91% selected i only; 27.45% selected both i and ii; 11.79% selected i, ii and v; 4.39% selected i and v; 3.18% selected i, ii, iv and v; and 3.18% selected i, ii and iv. On this basis, and out of 64 possible permutations, nearly 95% of all family firms at least selected i, which is understandable, because we would expect small to medium sized family firms to have a more operational classification; however, not excluding these, approximately 37% also selected iv and v, which is associated with the essence-based classification of a family firm.

“Personal and other services” was excluded and used as the benchmark industry.

Notable exceptions are the construction, accommodation, and personal services industries.

For a discussion on the relationship between capital intensity and labour productivity, see Wolff (1991).

Note that the measure of total workers, as the denominator in the part-time ratio, has not been converted to FTE workers and is simply reported as the total number of all employees in any given firm.

Considering that our sub-sample of the BLS is relatively small (i.e. the number of cross-sectional subjects, N = 3364, is greater than the number of time periods, T = 4), the family ownership dummy specified in Eq. 2 is, in fact, constant for each family firm across the entire period under analysis.

An important assumption of the random effects model is that the unobserved random disturbance, u i, is uncorrelated with the individual regressors in Eq. 3. As is the case with many panels, the Hausman test has revealed that the coefficients estimated by the efficient random effects estimator are not the same as those estimated by the consistent fixed effects estimator. In such cases a fixed effect model would be preferred; for reasons already stated, however, and to directly estimate the family firm intercept, we require a random effects approach. To overcome this issue, the Hausman–Taylor random effects procedure, with instruments, can be used to control for endogeneity (Hausman and Taylor 1981).

References

Agrawal, A., & Nagarajan, N. J. (1990). Corporate capital structure, agency costs, and ownership control: The case of all-equity firms. American Finance Association, Journal of Finance, 45(4), 1325–1331.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328.

Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding family ownership and the agency cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 68(2), 263–285.

Aronoff, C. E., & Ward, J. L. (1995). Family-owned businesses: A thing of the past or a model for the future? Family Business Review, 8(2), 121–130.

Arrow, K. J. (1974). The measurement of real value added. New York: Academic Press.

Baltagi, B. H. (2001). Econometric analysis of panel data. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Barth, E., Gulbrandsen, T., & Schønea, P. (2005). Family ownership and productivity: The role of owner-management. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1–2), 107–127.

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1995). What to do (and not to do) with Time-Series Cross-Section Data. The American Political Science Review, 89(3), 634–647.

Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of social interactions. Journal of Political Economy, 82(1), 1063–1093.

Benedict, B. (1968). Family firms and economic development. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 24(1), 1–19.

Berle, A., & Means, G. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World.

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2006). The role of family in family firms. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 73–96.

Bhattacharya, U., & Ravikumar, B. (2001). Capital markets and the evolution of family businesses. The Journal of Business, 74(2), 187–219.

Bosworth, D., & Loundes, J. (2002). The dynamic performance of Australian enterprises. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne (Melbourne Institute Working Paper Series).

Burns, P., & Whitehouse, O. (1996). Family ties. Special report of the 3 i European Enterprise Center.

Carlson, S. (1909). A study on the pure theory of production. New York: Kelley & Millman, Inc.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Litz, R. A. (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and non-family firms: conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 335–354.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 23(4), 19–39.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (2003). Succession and nonsuccession concerns of family firms and agency relationship with nonfamily managers. Family Business Review, 16(2), 89–107.

Claessens, S., et al. (2002). Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2741–2771.

Cobb, C. W., & Douglas, P. H. (1928). A theory of production. The American Economic Review, 18(1), 139–165.

Daily, C. M., & Dollinger, M. J. (1992). An empirical examination of ownership structure in family and professionally managed firms. Family Business Review, 5(2), 117–136.

De Paola, M., & Scoppa, V. (2009). The role of family ties in the labour market. An interpretation based on efficiency wage theory. Review of Labour Economics and Industrial Relations, 15(4), 603–624.

DeAngelo, H., & DeAngelo, L. (2000). Controlling stockholders and the disciplinary role of corporate payout policy: a study of the Times Mirror Company. Journal of Financial Economics, 56(2), 153–207. doi:10.1016/S0304405X(00)000398.

Demsetz, H. (1983). The structure of ownership and the theory of the firm. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 375–390.

Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. (1985). The structure of corporate ownership: causes and consequences. The Journal of Political Economy, 93(6), 1155–1177.

Demsetz, H., & Villalonga, B. (2001). Ownership structure and corporate performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 7(3), 209–233. doi:10.1016/S0929-1199(01)00020-7.

Dreux, D. R. I. V. (1990). Financing family business: Alternatives to selling out or going public. Family Business Review, 3(3), 225–243.

Dyer, W. G. (1988). Culture and continuity in family firms. Family Business Review, 1(1), 37–50.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325.

Fiegener, M. K., Brown, B. M., Prince, R. A., & Marie File, K. (1996). Passing on strategic vision: Favored modes of successor preparation by CEOs of family and nonfamily firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 34(1), 15–26.

Gallo, M. A., & Vilaseca, A. (1996). Finance in family business. Family Business Review, 9(4), 387–401.

Goffee, R., & Scase, R. (1985). Proprietorial control in family firms: some functions of ‘quasi-organic’ management systems. Journal of Management Studies, 22(1), 53–68.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Takács Haynes, K., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J. L., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137.

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25.

Handler, W. C. (1994). Succession in family business: A review of the research. Family Business Review, 7(2), 133–157.

Harris, D., Martinez, J. I., & Ward, J. L. (1994). Is strategy different for the family-owned business? Family Business Review, 7(2), 159–174.

Hausman, J. A., & Taylor, W. E. (1981). Panel data and unobservable individual effects. Econometrica, 49(6), 1377–1398.

Hawke, A. (2000). The business longitudinal survey. The Australian Economic Review, 33(1), 94–99.

Hoch, I. (1958). Simultaneous equation bias in the context of the Cobb–Douglas production function. Econometrica, 26(4), 566–578.

Hoopes, D. G., & Miller, D. (2006). Ownership preferences, competitive heterogeneity, and family-controlled businesses. Family Business Review, 19(2), 89–101.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Lee, J. (2006). Family firm performance: Further evidence. Family Business Review, 19(2), 103–114.

Litz, R. A. (1995). The family business: Toward definitional clarity. Family Business Review, 8(2), 71–81.

Kirchhoff, B. A. & Kirchhoff, J. J. (1987). Family contributions to productivity and profitability in small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 25(4): 25–31.

Martikainen, M., Nikkinen, J., & Vähämaa, S. (2009). Production functions and productivity of family firms: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 49(2), 295–307.

McConaughy, D. L., Walker, M. C., Henderson, G. V., & Mishra, C. S. (1998). Founding family controlled firms: Efficiency and value. Review of Financial Economics, 7(1): 1–19.

McMahon, R. G. P., & Stanger, A. M. J. (1995). Understanding the small enterprise financial objective function. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 19(4), 21–39.

Mendershausen, H. (1938). On the significance of professor Douglas’ production function. Econometrica, 6(2), 143–153.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., Lester, R. H., & Cannella, A. A., Jr. (2007). Are family firms really superior performers? Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), 829–858.

Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2003). Agency problems in large family business groups. Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 27(4), 367–382.

Morck, R., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1988). Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 293–315.

Morck, R. K., Stangeland, D. A., & Yeung, B. (2000). Inherited wealth, corporate control and economic growth: The Canadian disease?. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moskowitz, M., & Levering, R. (1993). The ten best companies to work for in America. Business and Society Review, 85(1), 26–38.

Mundlak, Y. (1961). Empirical production function free of management bias. Journal of Farm Economics, 43(1), 44–56.

Nelly, R., & Rodríguez, T. (2008). Strategic planning and organizational integrity in family firms: Drivers for successful postintegration outcomes in M&A procedures. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Ouchi, W. G. (1980). Markets, bureaucracies, and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1), 129–141.

Palia, D., & Lichtenberg, F. (1999). Managerial ownership and firm performance: A re-examination using productivity measurement. Journal of Corporate Finance, 5(4), 323–339.

Parsons, D. O., Orley, C. A., & Richard, L. (1986). Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 2). Columbus: Elsevier.

Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. New York: Wiley.

Ramsey, J. B. (1969). Tests for specification errors in classical linear least-squares regression analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 31(2), 350–371.

Robinson, J. (1953). The production function and the theory of capital. The Review of Economic Studies, 21(2), 81–106.

Rosenblatt, P. C. (1985). The family in business. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ross, S. A. (1973). The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. American Economic Review, 63(2), 134–139.

Rutherford, M., Oswald, S., & Raymond, J. (2005). Commitment to employees: does it help or hinder small business performance? Small Business Economics, 24(2), 97–111.

Sato, K. (1976). The meaning and measurement of the real value added index. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 58(4), 434–442.

Sciascia, S., & Mazzola, P. (2008). Family involvement in ownership and management: Exploring nonlinear effects on performance. Family Business Review, 21(4), 331–345.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

Stavrou, E. T. (1999). Succession in family businesses: exploring the effects of demographic factors on offspring intentions to join and take over the business. Journal of Small Business Management, 37(3), 47–61.

Stulz, R. (1988). Managerial control of voting rights: Financing policies and the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 25–54.

Tagiuri, R., & Davis, J. (1996). Bivalent attributes of the family firm. Family Business Review, 9(2), 199–208.

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385–417.

Wall, R. A. (1998). An empirical investigation of the production function of the family firm. Journal of Small Business Management, 36(2), 24–32.

Ward, J. L. (1987). Kee** the family business healthy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ward, J. L. (1988). The special role of strategic planning for family businesses. Family Business Review, 1(2), 105–117.

Williamson, O. E. (1996). Transaction cost economics and the Carnegie connection. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 31(2), 149–155.

Wolff, E. N. (1991). Capital formation and productivity convergence over the long term. The American Economic Review, 81(3), 565–579.

Zahra, S. A. (2005). Entrepreneurial risk taking in family firms. Family Business Review, 18(1), 23–40.

Zellner, A., Kmenta, J., & Dreze, J. (1966). Specification and estimation of Cobb–Douglas production function models. Econometrica, 34(4), 784–795.

Zellweger, T. (2007). Time horizon, costs of equity capital, and generic investment strategies of firms. Family Business Review, 20(1), 1–15.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Grand Valley State University’s Family Owned Business Institute for their generous funding of this study. Further acknowledgements are extended to Dr. Gulasekaran for his econometric expertise and Dr. Khalid and Dr. Craig for their support in develo** this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barbera, F., Moores, K. Firm ownership and productivity: a study of family and non-family SMEs. Small Bus Econ 40, 953–976 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9405-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9405-9