Abstract

Mandarin has a special construction widely known as a ‘wh-conditional’, in which both the antecedent clause and the consequent clause are wh-clauses. Wh-conditionals are of interest to linguists because the wh-expressions in a wh-conditional must co-refer. How to make sense of the fusion of a conditional and two wh-clauses, as well as the nature of the co-reference relation, have been long-standing issues. Two competing approaches have been advanced to shed light on wh-conditionals: the indefinite approach (Cheng and Huang in Nat. Lang. Semant. 4(2):121–163, 1996; Chierchia in J. East Asian Linguist. 9: 1–54, 2000; a.o.), which treats wh-expressions as indefinites that exhibit dynamic potentials, and the question-categorial approach (**ang in Interpreting questions with non-exhaustive answers, Ph.D. thesis, 2016; **ang in Linguist. Philos., 2020a; Liu in Varities of alternatives, Ph.D. thesis, 2016; Liu in Varieties of alternatives: Focus particles and wh-expressions in Mandarin, 2017), which treats wh-clauses as questions denoting functions of various types (or categories). Both approaches face nontrivial challenges, but at the same time have unique advantages each. The goal of this paper is to devise an alternative approach that borrows insights from these two approaches but avoids their shortcomings. On the one hand, the proposed analysis treats wh-clauses as questions. On the other hand, it recognizes the dynamic potential of interrogative wh-expressions, i.e., their ability to introduce discourse referents. A wh-conditional is analyzed as quantification over the values of these discourse referents, which creates the impression of co-reference of the wh-expressions involved (via unselective binding). To the extent that the present analysis is on the right track, it extends the application of the dynamic potential of wh-expressions beyond anaphora.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The counterparts of if in Mandarin can occur in wh-conditionals (Lin 1996; Pan and Jiang 2015), as in (i) and (ii). These data further support that wh-conditionals are morphologically built on conditionals.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

However, according to Cheng and Huang (1996), the occurrence of rúgǔo and yàoshì is more restrictive in wh-conditionals than in ordinary conditionals. The distribution of these if-particles is not the main issue of this paper, and hence I will not include these particles in my examples.

-

(i)

Chierchia (1992, 2000) proposes that a conditional lacking an adverbial quantifier or a modal involves a covert always, which quantifies over situations. This paper does not tackle the issue whether a covert always or a covert necessity modal is involved in a conditional. Given that wh-conditionals often express regularities/rules that go beyond the actual world, as pointed out by a reviewer, I simply follow Kratzer (1981) and Cheng and Huang (1996) and assume that a covert necessity modal is involved.

Following Karttunen (1977), Liu and **ang both assume that a wh-expression lexically denotes an existential quantifier. However, the denotation is shifted in some way when they derive a question meaning.

Strictly speaking. the meaning paraphrased in (5) is not a conditional interpretation in the sense of the LKH approach. Crucially, the wh-antecedent clause is not taken to restrict the domain of possible worlds. As a consequence, a potential problem may arise in a wh-conditional with an overt adverb. For example, the wh-conditional in (i) is true in the following case: given ten situations where a person wins, only in two situations does the winner pay (Cheng and Huang 1996). This shows that the quantification given by hěnshǎojiàn ‘seldom’ only cares about situations in which a person wins, rather than all situations.

-

(i)

If the quantificational domain were not restricted, (i) could be true in the following scenario: suppose we have 100 situations in total and only in ten of them is there a person who wins; then the winner pays in all of these ten situations. Intuitively, the scenario falsifies (i). However, this problem is not very serious. The most direct solution is to assume that the information expressed by the wh-antecedent clause can be accommodated into the domain of the adverb (see Dayal’s (1997) discussion on the quantificational variability of ever-free relatives).

-

(i)

In the literature there also exists a ‘correlative/free-relative’ approach to wh-conditionals. In this approach, wh-conditionals are taken to be correlatives or ever-free relatives (Bruening and Tran 2006; Luo and Crain 2011; Huang 2010). Cheng and Huang (1996) and Liu (2016) have pointed out problems with this view, so I will not review it in this paper.

In this paper, a linguistic expression introducing a dref is superscripted with an index, while the anaphor referring to the dref is subscripted with the same index.

In principle, any question semantics can be dynamicized. I have chosen to work with Hamblin semantics just because most studies on the semantics of Mandarin questions (Dong 2009, 2018; He 2011; Li and Law 2016) follow Hamblin semantics. They have argued that the composition mechanism assumed in Hamblin semantics can handle a wider range of phenomena.

It should be noted that degree wh-expressions can only be interpreted as indefinites in the scope of the negation marker méi ‘not’. Other indefinite use licensors, like conditionals, polar questions, and modals, cannot license the indefinite use of these wh-expressions.

In Mandarin, wèishěnme is ambiguous between a ‘why’ reading and a ‘for what’ reading. The latter is not a real wh-adverb and can be analyzed as a preposition phrase. In order to avoid this ambiguity, I use the passive construction in (14). According to Tsai (2008), wèishěnme with the ‘for what’ reading is about the purpose of the agent and hence cannot be used in a passive sentence.

Almost all wh-expressions can be used in wh-conditionals (Cheng and Huang 1996; Liu 2016), but reason zěnme ‘how come’ and sentence-initial wèishěnme ‘ why’ cannot (Huang 2018), as exemplified below.

-

(i)

I suggest that the ungrammaticality of these examples is due to the high syntactic position of the relevant wh-expressions. Tsai (2008) has convincingly argued that zěnme and the sentence initial wèishěnme occupy a position in the left periphery of a sentence. However, the antecedent clause and the consequent clause of a wh-conditional may not have a full left periphery, because neither clause allows topic expressions, as evidenced by (ii).

-

(ii)

Consequently, the wh-clauses embedded in a wh-conditional may not have a syntactic position to locate reason zěnme and sentence-initial wèishěnme.

-

(i)

Both **ang (2016, 2020a) and Liu (2016, 2017) syncategorematically assign meaning postulates to wh-conditionals, rather than categorematically deriving the meaning of wh-conditionals based on that of ordinary conditionals. This kind of treatment does not explain the connection between these two types of conditionals.

The structured meaning approach to questions (von Stechow 1991) as well has been exploited to derive short answers in the literature (Krifka 2001a; Weir 2018). Liu’s (2016) formal analysis is built on a variant of the structured meaning approach. However, the derivation of short answers in the structured meaning approach is not essentially different from that in the categorial approach. In particular, the structured meaning of a question is modeled as a pair containing a set of entities and a function, and this pair also plays an essential role in deriving short answers. As a result, all the challenges to the categorial approach that are presented in the following subsections also apply to the structured meaning approach.

Note that

is bound by shěnme, even though it is not in the syntactic scope of the latter. Therefore, this binding relation is a dynamic one. It calls for a dynamic semantics of wh-expressions. I will return to this issue in Sect. 3.

is bound by shěnme, even though it is not in the syntactic scope of the latter. Therefore, this binding relation is a dynamic one. It calls for a dynamic semantics of wh-expressions. I will return to this issue in Sect. 3.Note that the wh-expressions in (33) range over kinds; thus, shěnme cài means ‘what kind of dish’, while shěnme jiǔ means ‘what kind of wine’. See Lin (1999) for a detailed discussion of the domain of shěnme.

See **ang (2020a, fn.34) for a potential solution to this issue.

Although the existing analyses cannot generate correct short answers to conjunctions of wh-clauses, re-formulating the categorial approach with variable-free semantics (Jacobson 1999) may resolve this problem, as pointed out by a reviewer. Briefly speaking, variable-free semantics assumes that a sentence with a free pronoun denotes a function to propositions. For example, Ada ate it denotes λx.eat(x)(a). In this sense, the meaning of a sentence with a pronoun in variable-free semantics may be the same as that of a wh-clause assumed in the categorial approach. In variable-free semantics, composing the meaning of the sentence He bought it and she was happy yields a function λxλyλz.buy(y)(z)∧happy(x). With the same mechanism, the conjunction of wh-clauses Who bought what and who was happy is expected to denote the same function, which indeed characterizes a set of triples. This direction sounds promising, but still raises a potential issue that should be addressed. Specifically, in variable-free semantics, such an analysis may predict that wh-clauses could behave similarly to sentences with pronouns with respect to other aspects of grammar, in particular, binding. That is, a wh-expression could be bound as a pronoun. This is an unwelcome prediction.

In Mandarin, polar questions can also be marked by the sentence-final particle mā. This type of polar question cannot occur in a conditional either. However, the reason might not be semantic but syntactic. The particle mā is usually considered a force operator and occupies the highest functional head of a matrix question. As discussed in footnote 12, the clauses embedded in a conditional may not have a full left periphery. Hence, the particle mā is syntactically prevented from occurring in a conditional.

Alternative questions cannot be embedded in conditionals either, as seen in (i). Alternative questions admit short answers that look similar to the ones to wh-questions. For example, the question Does Ada or Bob lose can be answered by Ada. Given this, it’s surprising that they don’t give rise to conditionals similar to wh-conditionals.

-

(i)

In fact, the analysis of alternative questions is debated. Biezma and Rawlins (2012), Erlewine (2014), and Li and Law (2016) analyze English and Mandarin alternative questions in the same way as wh-questions, but Han and Romero (2004) and Huang and Ray (2010) argue that alternative questions involve clausal coordination and ellipsis. Empirically, there are also dissimilarities between alternative questions and wh-questions. First, there are multiple-wh questions, but not multiple-alternative questions (e.g., Did Ann or Bob eat apples or pears? doesn’t have a pair-list answer like Ann ate apples and Bob pears). Second, universal quantifiers can quantify into wh-questions, leading to pair-list readings, but not into alternative questions. To my knowledge, these phenomena have not received a satisfactory account. They indicate that alternative questions might be different from wh-questions in their structure and meaning. An argument built on alternative questions may not necessarily challenge or support an account for wh-conditionals. Consequently, this paper will not include an account for the unacceptability of (i) and leave it for future research.

-

(i)

In this example, the first wh-clause contains multiple wh-expressions and may lead to a pair-list reading. The pair-list reading is compatible with such a situation: given a set of boys, each lacks a different thing and for each of these things there is a girl who has it. In this reading, the null pronoun is evaluated relative to the dependency consisting of different boy–thing pairs, i.e., for each boy, the null pronoun refers to the thing that he lacks, not a thing that all the boys lack. In Sect. 6.3.1, I will offer a formal analysis for multiple-wh clauses embedded in wh-conditionals. However, modeling reference to dependencies requires extra machinery not related to the main issue of the present paper. I reserve the discussion of this issue for another occasion.

(42) is modified from Liu’s (2016) example (56) (p. 146).

The two ways of determining functional dependencies are close to Barker’s (1995) distinction between lexical possessives and extrinsic possessives. A lexical possessive, like John’s father, has a possession relation encoded in the lexical meaning of the possessee, whereas an extrinsic possessive, like John’s cat, expresses a possession relation determined contextually.

Section 7 will discuss a possibility of generalizing the functional relation to wh-conditionals with co-indexed wh-expressions. Briefly, an ordinary wh-conditional might involve an identity function in the consequent clause. The identity function could help us understand the fact that the co-indexed wh-expressions in a wh-conditional must be morphologically identical.

As 〚⋅〛 maps a linguistic expression to a static meaning, \([\!\![\cdot ]\!\!]_{d}\) maps a linguistic expression to a dynamic meaning.

Hardt (1999) proposes an alternative way to model the distinction between drefs. Info-states are represented as assignments, and a discourse center is treated as a distinguished variable whose value can be reassigned. The analysis proposed in this paper can also be recast in Hardt’s formalism, without any substantial change to its essence. I use lists because the distinction between drefs is visually more explicit.

Independent motivation for the creation of two sublists stems from many crosslinguistic phenomena, including grammatical centering in Kalaallisut, reference to tense in English, and null pronouns and aspect particles in Mandarin (Bittner 2014).

A wh-question can contain a non-wh expression that is prosodically prominent in some situations, like (i). The subject Ann in the final question bears an accent and contrasts with Bob.

-

(i)

I am interested in what Ann and Bob ate. Let’s start with Ann. What did [Ann]

eat?

eat?

In the literature, Ann is called a ‘contrastive topic’, which generates a set of questions not uttered explicitly (Büring 2003; Tomioka 2010; Constant 2014; Krifka 2017). Although it bears an accent, its semantic contribution is not the same as that of focused elements.

-

(i)

In this paper, I leave open the issue whether wh-expressions evoke focus alternatives like other focused expressions. One view is that wh-expressions only give rise to alternatives in the focus meaning dimension (Beck 2006; Kotek 2014; Kotek and Erlewine 2018; Dong 2018; Uegaki 2018). The other view is that wh-expressions inherently denote alternative sets, so that it is not necessary to assume that they evoke focus alternatives (Ishihara 2003; Eckardt 2007; Li and Law 2016). In order to avoid unnecessary complexity, I use the original Hamblin semantics and do not posit another dimensional meaning for wh-expressions.

Murray (2010) assumes that a wh-question also introduces sets of possible worlds as drefs; these are added to the bottom lists. This assumption is not adopted in my analysis.

Existential Disclosure as defined in Dekker (1993) is couched in Dynamic Montague Grammar (Groenendijk and Stokhof 1990) and exploits cross-sentential binding to retrieve drefs. By contrast, in my definition (54), the subtraction of lists is used to retrieve drefs. In most cases the two procedures give rise to the same result, but the present procedure has an advantage when retrieving values of wh-drefs in a multiple-wh question. A comparison of these two procedures is provided in Appendix B.

Applying

to the existential sentence A girl won results in a dynamic predicate, as in (i). As a result,

to the existential sentence A girl won results in a dynamic predicate, as in (i). As a result,  seems to wipe out the existential operator (this is the reason why this operation is dubbed Existential Disclosure).

seems to wipe out the existential operator (this is the reason why this operation is dubbed Existential Disclosure).-

(i)

-

(i)

The blocking effect is closely related to the Maxim of Manner, which requires that when two linguistic expressions are assertable, the simpler one should be used (Grice 1989; Katzir 2008). However, the blocking effect may not be derived from the Maxim of Manner, violation of which generally does not lead to infelicity. Its status is more similar to the well-known pragmatic constraint ‘Maximize Presupposition!’ (Heim 1991; Sauerland 2008; Schlenker 2012; Lauer 2016; a.o.).

If the present account is on the right track, the adverbial quantifier/modal involved in a conditional should have the potential to quantify over the values of drefs introduced by other expressions, like indefinites. However, two indefinites embedded in a conditional cannot co-refer, as shown in (i).

-

(i)

The unacceptability of (i) indicates that we would have to impose some sort of novelty condition on indefinites, as many dynamic theories assume (Heim 1982; Dekker 1996; a.o.). For example, the two occurrences of the indefinite yí-gè rén ‘a person’ must introduce distinct entities for drefs. Simultaneously, we have to prevent the application of this novelty condition to wh-expressions. In ordinary wh-questions, every occurrence of a wh-expression independently denotes a set of dynamic names. There is no anaphoric dependency between these. By contrast, in wh-conditionals, the values associated with wh-drefs are abstracted over by

and become variables. If the novelty condition does not apply to wh-expressions, these variables can be bound by one operator.

and become variables. If the novelty condition does not apply to wh-expressions, these variables can be bound by one operator.Chierchia (1995, 2000) proposes that it is possible to do away with the novelty condition. The effect of the novelty condition can be derived via a syntactic binding principle instead, according to him. Briefly, Chierchia re-defines syntactic binding as follows: an argument A binds another argument B iff A and B are co-indexed and either (i) A c-commands B or (ii) A is co-indexed with a quantificational adverb that c-commands B. According to Chierchia, the syntactic structure of (i) is analyzed as (ii).

-

(ii)

[Libai invited [a person]1] [ALWAYS1 [Dufu will invite [a person]1]]

In (ii), the first indefinite is co-indexed with the covert ALWAYS that c-commands the second indefinite. As a result, the first indefinite binds the second one. As a referential expression in the sense of syntactic binding, the indefinite cannot be bound. In contrast, Chierchia postulates that wh-expressions are pronominal elements so that they can be bound in conditionals. However, it is not clear why wh-expressions should be pronominal. Unlike pronouns, wh-expressions cannot be anaphoric to other expressions.

-

(i)

**ang (2020a) challenges this observation based on examples like (i). The continuation indicates that the speaker will invite more people than the ones that the addressee would like to meet.

-

(i)

However, there are at least two factors that may weaken this challenge. First, (i) becomes deviant without dàn ‘but’. It is known that but has a counter-expectational use. It indicates that the wh-conditional expresses an expectation that the speaker will invite only the people that the addressee wants to meet. According to previous studies (Winter and Rimon 1994; Toosarvandani 2014; a.o.), the expectation countered by but is a kind of weaker entailment rather than just a pragmatic implicature. Therefore, the fact that dàn is required here means that the wh-conditional does semantically give rise to a certain type of maximality inference. Second, (i) expresses an irrealis mood, i.e., the speaker’s invitation does not happen at the speech time. By contrast, when a wh-conditional expresses a realis mood, the maximality inference cannot be wiped out, as shown in (ii).

-

(ii)

Due to these factors, the acceptability of (i) does not decisively show that wh-conditionals do not carry a maximality inference. The precise nature of this maximality inference will have to await future research.

-

(i)

Li and Law (2016) show that focus intervention effects are not restricted to wh-questions, but also appear in unconditionals, existential-wh constructions, and disjunctive sentences.

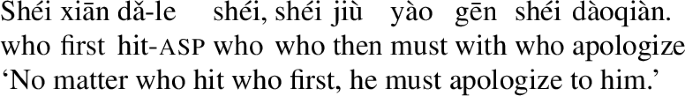

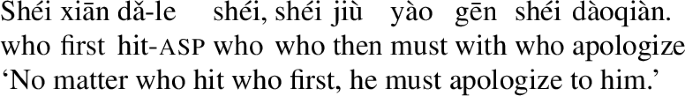

It is observed that multiple-wh questions can also admit single-pair answers, as in (i). Correspondingly, multiple-wh conditionals also have a ‘single-pair’ reading, as in (ii). Its meaning can be represented as: ‘For every accessible world w and two people x and y, if x hits y first in w, then x apologizes to y in w’.

-

(i)

-

A:

Who hit who first?

-

B:

Bob hit Carl first.

-

A:

-

(ii)

Both examples are felicitous when the context involves only two people and one hit the other first. So, the question in (i) is resolved by a single pair of two people, and the multiple-wh conditional in (ii) quantifies over pairs of people. This reading can be derived via the basic composition of question meaning, i.e., \([\!\![\text{who hit who first} ]\!\!]_{d} = [\!\![\text{who} ]\!\!]_{d} \circledast \big ( \big \{ [\!\![\text{hit} ]\!\!]_{d} \big \} \circledast [\!\![\text{who} ]\!\!]_{d} \big ) = \left \{\ \beta \bullet [\!\![\text{hit} ]\!\!]_{d} \bullet \beta '\ \left |\ \beta , \beta ' \in [\!\![\text{who} ]\!\!]_{d} \right . \right \} \).

-

(i)

In dynamic semantics, the present analysis is close to Bumford’s (2015) account of the pair-list reading in questions with quantifiers (e.g., the availability of pair-list readings in questions like Which dish did everyone order). In Bumford’s account, the dependency established in a pair-list answer to Who ordered which dish is also represented as a list of entities alternating between people and dishes.

de Swart (1991) argues that quantificational adverbs quantify over events or situations. This view is not incompatible with unselective binding. In (102), the situation variable is also bound by the quantificational adverb. Moreover, on the indefinite approach, the wh-expressions in (100) have to be bound by the same quantificational operator. Otherwise, the co-reference of the wh-expressions would not be explained.

One way to repair (102) is to assume that the wh-expressions in (100) introduce variables ranging over a maximal set of people and a maximal set of dishes (cf. Chierchia 2000; Simon Charlow p.c.). In other words, (102) is revised as ‘For most situations s, a maximal set of people X, and a maximal set of dishes Y s.t. X ordered Y, X ate Y’. This solution may work when wh-expressions are number neutral, like who or what. However, in (100), the first wh-expression nǎ-gè rén ‘which person’ can only range over singular entities, because of the singular classifier gè. Moreover, even if the second wh-expression in (100) is changed to a morphologically singular one, as in (i), the sentence has the same meaning, except that it now presupposes that everyone ordered one dish.

-

(i)

Huang (2018) modifies Cheng and Huang’s (1996) analysis and suggests that the variables contributed by wh-expressions be invariably bound by a universal operator in wh-conditionals, instead of the operator offered by a conditional. This modified analysis may avoid the first problem, but it is not clear where the universal operator comes from compositionally. The quantificational force of a conditional is not always universal but varies along with the adverbials/modals included in it.

-

(i)

The value of the choice function

is contextually determined, as Kratzer (1998) proposes when she implements the meaning of specific indefinites.

is contextually determined, as Kratzer (1998) proposes when she implements the meaning of specific indefinites.The same kind of mention-some reading is also available for wh-conditionals with an overt quantificational adverb, as shown in (i). The meaning of this sentence is represented in (ii).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

In (ii), tōngcháng binds both the situation variable s and the entity variable x. Because

′ encodes the choice function, x is just one place that sells wine in s. Quantifying over situation–entity pairs (x,s) is equivalent to quantifying over situations s such that s associates with a certain liquor store x in s, not all liquor stores in s. Therefore, (ii) indicates that in most situations the speaker will go to one liquor store.

′ encodes the choice function, x is just one place that sells wine in s. Quantifying over situation–entity pairs (x,s) is equivalent to quantifying over situations s such that s associates with a certain liquor store x in s, not all liquor stores in s. Therefore, (ii) indicates that in most situations the speaker will go to one liquor store.-

(i)

In my proposal, a wh-expression denotes a set of dynamic GQs, but the set itself is not dynamic. Simon Charlow (p.c.) points out that a problem arises when we need to bind a variable inside the wh-expression as with, for instance, which of his paintings. How many paintings are included in the set denoted by the wh-expression depends on the value of the pronoun. However, the restriction of the alternatives (i.e., \(x \in \textsf {human}_{w_{0}}\) in (118)) is not dynamic, so the value of the pronoun cannot be determined. One solution is to assume that which contributes a set of choice functions, which pick out one member from a set. Then, the denotation of which of his paintings can informally be represented as \(\left \{ f \{ x \mid x \in \text{his paintings} \}\ \left |\ f \in \textsf {CH} \right . \right \}\). The pronoun occurs inside the alternative set. Another solution is to dynamicize the Hamblin semantics with the use of Charlow’s (to appear) dynamic alternative semantics, which makes alternative sets dynamic yet has only minimal impact otherwise.

References

Aloni, Maria, and Robert van Rooy. 2002. The dynamics of questions and focus. In Proceedings of SALT 12, 20–39, ed. Brendan Jackson. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

AnderBois, Scott. 2012. Focus and uninformativity in Yucatek Maya questions. Natural Language Semantics 20: 349–390.

Aoun, Joseph, and Audrey Yen-hui Li. 1993. Wh-elements in situ: Syntax or LF? Linguistic Inquiry 24(2): 199–238.

Barker, Chris. 1995. Possessive descriptions. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14(1): 1–56.

Berman, Stephen. 1991. On the semantics and logical form of wh-clauses. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Biezma, Maria, and Kyle Rawlins. 2012. Responding to alternative and polar questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 35: 361–406.

Bittner, Maria. 2014. Temporality: Universals and variation. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Brasoveanu, Adrian. 2010. Decomposing modal quantification. Journal of Semantics 27: 437–527.

Bruening, Benjamin, and Thuan Tran. 2006. Wh-conditionals in Vietnamese and Chinese: Against unselective binding. In Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 32, eds. Rosyln Burns, Chundra Cathcart, Emily Cibelli, Kyung-Ah Kim, and Elise Stickles, 49–60. Berkeley: University of California Berkeley.

Bumford, Dylan. 2015. Incremental quantification and the dynamics of pair-list phenomena. Semantics & Pragmatics 8: 1–70.

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On d-trees, beans, and b-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 511–545.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2003. Free not to ask: On the semantics of free relatives and wh-words cross-linguistically. Ph.D. thesis, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles.

Chao, Yuen Ren. 1968. A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Charlow, Simon. 2014. On the semantics of exceptional scope. Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

Charlow, Simon. 2017. A modular theory of pronouns and binding. In Proceedings of logic and engineering of natural language semantics 14, Tokyo, Japan.

Charlow, Simon. To appear. Static and dynamic exceptional scope. Journal of Semantics, https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/004650.

Chen, Sherry Yong. 2020. Deriving wh-correlatives in Mandarin Chinese: Wh-movement and (island) identity. In Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 50, eds. Maryam Asatryan, Yixiao Song, and Ayana Whitmal, Vol. 1, 101–110. Amherst: GLSA.

Cheng, Lisa L.-S. and C.-T. James Huang. 1996. Two types of donkey sentences. Natural Language Semantics 4(2): 121–163.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1991. On the typology of wh-questions. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Cheung, Candice Chi-Hang. 2007. Move or not move? A case study of wh-conditionals in Mandarin. In Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 37, eds. Emily Elfner and Martin Walkow. Vol. 1, 153–164. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1992. Anaphora and dynamic binding. Linguistics and Philosophy 15: 111–183.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1993. Questions with quantifiers. Natural Language Semantics 1(2): 181–234.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1995. Dynamics of meaning. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2000. Chinese conditionals and the theory of conditionals. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 9: 1–54.

Comorovski, Ileana. 1996. Interrogative phrases and the syntax-semantics interface. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Constant, Noah. 2014. Contrastive topic: Meanings and realizations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Cremers, Alexandre. 2018. Plurality effects in an exhaustification-based theory of embedded questions. Natural Language Semantics 26: 193–251.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1996. Locality in wh-quantification: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1997. Free relatives and ever: Identity and free choice readings. In Proceedings of SALT 7, ed. Aaron Lawson, 99–116. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Dekker, Paul. 1993. Existential disclosure. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(6): 561–588.

Dekker, Paul. 1994. Predicate logic with anaphora. In Proceedings of SALT 9, eds. Mandy Harvey and Lynn Santelmann, 79–95. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Dekker, Paul. 1996. The values of variables in dynamic semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 19(3): 211–257.

Dong, Hongyuan. 2009. Issues in the semantics of Mandarin questions. Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University.

Dong, Hongyuan. 2018. Semantics of Chinese questions: An interface approach. London: Routledge.

Dotlačil, Jakub, and Floris Roelofsen. 2018. Dynamic inquisitive semantics: Anaphora and questions. In Sinn und Bedeutung 23, eds. M. Teresa Espinal, Elena Castroviejo, Manuel Leonetti, Louise McNally, and Cristina Real-Puigdollers, 365–382. Bellaterra: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Dotlačil, Jakub, and Floris Roelofsen. 2020. A dynamic semantics of single-wh and multiple-wh questions. In Proceedings of SALT 30, eds. Joseph Rhyne, Kaelyn Lamp, Nicole Dreier, and Chloe Kwon, 376–395. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Eckardt, Regine. 2007. Inherent focus on wh-phrases. In Proceedings of Sinn and Bedeutung 11, eds. Louise McNally and Estella Puig-Waldmueller, 209–228. University of Konstanz.

Engdahl, Elisabet. 1986. Constituent questions. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Erlewine, Michael Y. 2014. Alternative questions through focus alternatives in Mandarin Chinese. In Proceedings of the Chicago Linguistic Society 48, eds. Andrea Beltrama, Tasos Chatzikonstantinou, Jackson L. Lee, Mike Pham, and Diane Rak, 221–234. Chicago: CLS.

Farkas, Donka, and Kim Bruce. 2010. On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics 27: 81–118.

Fox, Danny. 2012. Lectures on the semantics of questions. Unpublished lecture notes, MIT.

Fox, Danny. 2013. Mention-some readings of questions. MIT seminar notes.

George, Benjamin. 2011. Question embedding and the semantics of answers. Ph.D. thesis, University of California at Los Angeles.

Ginzburg, Jonathan, and Ivan Sag. 2000. Interrogative investigations. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Grice, Paul. 1989. Logic and conversation. In Studies in the way of words, 22–40. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1984. Studies on the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1989. Type-shifting rules and the semantics of interrogatives. In Properties, types and meaning, eds. Gennaro Chierchia, Barbara H. Partee, and Raymond Turner. Vol. 2, 21–68. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1990. Dynamic Montague grammar. In Papers from the 2nd symposium on logic and language, eds. L. Kálmán and L. Polós, 3–48. Budapest, Hungary.

Guerzoni, Elena. 2007. Weak exhaustivity and whether: A pragmatic approach. In Proceedings of semantics and linguistic theory 17, eds. T. Friedman and M. Gibson, 112–129. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Hagstrom, Paul. 1998. Decomposing questions. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Haida, Andreas. 2007. The indefiniteness and focusing of wh-words. Ph.D. thesis, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Hamblin, Charles. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10(1): 41–53.

Han, Chung-hye, and Maribel Romero. 2004. The syntax of whether/Q...or questions: Ellipsis combined with movement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22(3): 527–564.

Hardt, Daniel. 1999. Dynamic interpretation of verb phrase ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 22(2): 185–219.

Hausser, Roland, and Dietmar Zaefferer. 1979. Questions and answers in a context-dependent Montague grammar. In Formal semantics and pragmatics for natural languages, eds. F. Guenthner and S. J. Schmidt, 339–358. Dordrecht: Reidel.

He, Chuansheng. 2011. Expansion and closure: Towards a theory of wh-construals in Chinese. Ph.D. thesis, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Heim, Irene. 1991. Artikel und Definitheit. In Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 487–535. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Henderson, Robert. 2014. Dependent indefinites and their post-suppositions. Semantics & Pragmatics 7: 1–58.

Hendriks, Hermans. 1993. Studied flexibility: Categories and types in syntax and semantics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam.

Hua, Dongfan. 2000. On wh-quantification. Ph.D. thesis, City University of Hong Kong.

Huang, C.-T. James. 2018. Analyticity and wh-conditionals as unselective binding par excellence. Presented at the International Symposium Frontiers in Linguistics, Bei**g, Oct. 2018.

Huang, and Rui-heng Ray. 2010. Disjunction, coordination, and question: a comparative study. Ph.D. thesis, National Taiwan Normal University.

Huang, Yahui. 2010. On the form and meaning of Chinese bare conditionals: Not just whatever. Ph.D. thesis, University of Texas at Austin.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2003. Intonation and interface conditions. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Jacobson, Pauline. 1995. On the quantificational force of English free relatives. In Quantification in natural languages, eds. Barbara Partee, Emmon Bach, and Angelika Kratzer, 451–486. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Jacobson, Pauline. 1999. Towards a variable-free semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy 22(2): 117–184.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2016. The short answer: Implications for direct compositionality (and vice versa). Language 92: 331–375.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1976. Discourse referents. In Syntax and semantics, ed. James D. McCawley. Vol. 7, 363–385. San Diego: Academic Press.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1(1): 3–44.

Katzir, Roni. 2008. Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30: 669–690.

Kotek, Hadas. 2014. Composing questions. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Kotek, Hadas. 2017. Intervention effects arise from scope-taking across alternatives. In Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 47, eds. Andrew Lamont and Katerina Tetzloff. Vol. 2, 457–466. Amherst: GSLA.

Kotek, Hadas, and Michael Y. Erlewine. 2018. Covert pied-pi** in English multiple wh-questions. Linguistic Inquiry 49: 781–812.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1981. The national category of modality. In Words, worlds and context, eds. H. Eikmeyer and H. Rieser, 109–158. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1989. An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguistics and Philosophy 12(5): 607–653.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Focus. In Handbook of contemporary semantic theory, eds. T. Vennemann and Arnim von Stechow. Malden: Blackwell.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1998. Scope or pseudoscope? Are there wide-scope indefinites? In Events and grammar, ed. Susan Rothstein, 163–196. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2002. Facts: Particulars or information units? Linguistics and Philosophy 25(5): 655–670.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Proceedings of the Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed. Yukio Otsu. Vol. 3, 1–25. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001a. For a structured meaning account of questions and answers. In Audiatur vox sapientiae: A festschrift for Arnim von Stechow, eds. Caroline Féry and Wolfgang Sternefeld, 287–319. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001b. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9(1): 1–40.

Krifka, Manfred. 2017. Focus and contrastive topics in question and answer acts. Ms., Humboldt University.

Lauer, Sven. 2016. On the status of ‘Maximize Presupposition’. In Proceedings of SALT 26, eds. Mary Moroney, Carol Rose Little, Jacob Collard, and Dan Burgdorf, 980–1001. Ithaca: CLC Publications.

Lewis, David. 1975. Adverbs of quantification. In Formal semantics of natural language, ed. E. L. Keenan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Li, Audrey Yen-Hui. 1992. Indefinite wh in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 1(2): 12–155.

Li, Haoze. 2020. A dynamic semantics for wh-questions. Ph.D. thesis, New York University.

Li, Haoze, and Jess H.-K. Law. 2016. Alternatives in different dimensions: A case study of focus intervention. Linguistics and Philosophy 39: 201–245.

Lin, Jo-Wang. 1996. Polarity licensing and wh-phrase quantification in Chinese. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Lin, Jo-Wang. 1998. On existential polarity wh-phrases in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 7(3): 219–255.

Lin, Jo-Wang. 1999. Double quantification and the meaning of shenme ‘what’ in Chinese bare conditionals. Linguistics and Philosophy 22(6): 573–593.

Link, Godehard. 1983. The logical analysis of plurals and mass terms: A lattice-theoretical approach. In Meaning, use and interpretation of language, eds. R. Bäuerle, C. Schwarze, and Arnim von Stechow, 302–323. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Liu, Mingming. 2016. Varities of alternatives. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University.

Liu, Mingming. 2017. Varieties of alternatives: Focus particles and wh-expressions in Mandarin. Berlin and Bei**g: Springer and Peking University.

Luo, Qiongpeng, and Stephen Crain. 2011. Do Chinese wh-conditionals have relatives in other languages? Language and Linguistics 12: 753–798.

Murray, Sarah. 2010. Evidentiality and the structure of speech acts. Ph.D. thesis, Rutgers University.

Murray, Sarah. 2014. Varieties of update. Semantics & Pragmatics 7: 1–53.

Muskens, Reinhard. 1996. Combining Montague semantics and discourse representation. Linguistics and Philosophy 19(2): 143–186.

Nicolae, Andreea. 2013. Any questions? Polarity as a window into the structure of questions. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University.

Pan, Haihua, and Yan Jiang. 2015. The bound variable hierarchy and donkey anaphora in Mandarin Chinese. International Journal of Chinese Linguistics 2: 159–192.

Roelofsen, Floris, and Donka Farkas. 2015. Polarity particle responses as a window onto the interpretation of questions and assertions. Language 91: 359–414.

Roelofsen, Floris, Michele Herbstritt, and Maria Aloni. 2019. The *whether puzzle. In Questions in discourse, eds. Klaus von Heusinger, Malte Zimmerman, and Edgar Onea, 172–197. Leiden: Brill.

Romero, Maribel. 2015. Surprise-predicates, strong exhaustivity and alternative questions. In Proceedings of SALT 25, 225–245. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1(1): 117–121.

van Rooy, Robert. 1998. Modal subordination in questions. In Proceedings of Twendial’98, eds. J. Hulstijn and A. Nijholt, 237–248. University of Twente.

Sauerland, Uli. 2008. Implicated presuppositions. In The discourse potential of underspecified structures, ed. Anita Steube, 581–600. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2012. Maximize Presupposition! and Gricean reasoning. Natural Language Semantics 20: 391–429.

Sharvit, Yael, and Jungmin Kang. 2016. Fragment functional answers. In Proceedings of SALT 26, eds. Mary Moroney, Carol-Rose Little, Jacob Collard, and Dan Burgdorf 1099–1118. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Shi, Dingxu. 1994. The nature of Chinese emphatic sentences. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3(1): 81–100.

Shimoyama, Junko. 2006. Indeterminate phrase quantification in Japanese. Natural Language Semantics 139–173(14): 2.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1991. Focusing and backgrounding operators. In Discourse particles: Descriptive and theoretical investigations on the logical, syntactic, and pragmatic properties of discourse particles in German, ed. Werner Abraham, 37–84. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

von Stechow, Arnim, and Thomas Ede Zimmermann. 1984. Term answers and contextual change. Linguistics 22: 3–40.

de Swart, Henriëtte. 1991. Adverbs of quantification. New York: Garland.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2007. Pragmatics of LF intervention effects: Japanese and Korean WH-interrogatives. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 1570–1590.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2010. A scope theory of contrastive topics. Iberia 2(1): 113–130.

Toosarvandani, Maziar. 2014. Contrast and the structure of discourse. Semantics & Pragmatics 7: 1–57.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 2013. An analysis of prosodic f-effects in interrogatives: Prosody, syntax and semantics. Lingua 124: 131–175.

Tsai, Wei-Tien Dylan. 1994. On economizing the theory of A-bar dependencies. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Tsai, Wei-Tien Dylan. 1999. On lexical courtesy. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 8(1): 39–73.

Tsai, Wei-Tien Dylan. 2008. Left periphery and how-why alternations. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 17(2): 83–115.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2018. A unified semantics for the Japanese Q-particle ka in indefinites, questions and disjunctions. Glossa 3: 1–45.

Wang, **n. 2016. The logical-grammatical features of the ‘Shenme... Shenme’ sentence and its deduction. Luojixue Yanjiu [Studies in Logic] 9: 63–80.

Weir, Andrew. 2018. Cointensional questions, fragment answers, and structured meanings. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 21, eds. Robert Truswell, Chris Cummins, Caroline Heycock, Brian Rabern, and Hannah Rohde, 1289–1306. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Willis, Paul M. 2008. The role of topic-hood in multiple-wh question semantics. In Proceedings of the 27th West Coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. Kevin Ryan, 87–95. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Winter, Yoad, and Mori Rimon. 1994. Contrast and implication in natural language. Journal of Semantics 11: 365–406.

**ang, Yimei. 2016. Interpreting questions with non-exhaustive answers. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University.

**ang, Yimei. 2020a. A hybrid categorial approach to question composition. Linguistics and Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09294-8.

**ang, Yimei. 2020b. Quantifying-into wh-dependencies: Composing multi-wh-questions and questions with quantifiers. Ms, Rutgers University.

Yang, Yang. 2018. The two sides of wh-indeterminates in Mandarin: A prosodic and processing account. Ph.D. thesis, Leiden University.

Zimmermann, Thomas Ede. 1985. Remarks on Groenendijk and Stokhof’s theory of indirect questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 8: 431–448.

Acknowledgement

This paper is based on Chapter 3 of my dissertation (Li 2020). I am very grateful to my committee: Anna Szabolcsi, Simon Charlow, Philippe Schlenker, Chris Barker, and Adrian Brasoveanu. It also benefited from helpful feedback from many people: Lucas Champollion, Lisa Cheng, Jim Huang, Jess Law, Mingming Liu, Floris Roelofsen, Yimei **ang, two anonymous reviewers of Natural Language Semantics, the editors Angelika Kratzer and Irene Heim, and the copy-editor Christine Bartels. I also thank the audiences at a NYU Semantics Group Talk, MACSIM-8 (NYU), SALT-29 (UCLA), and TEAL-12 (University of Macau). I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant NO.: 18ZDA291).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

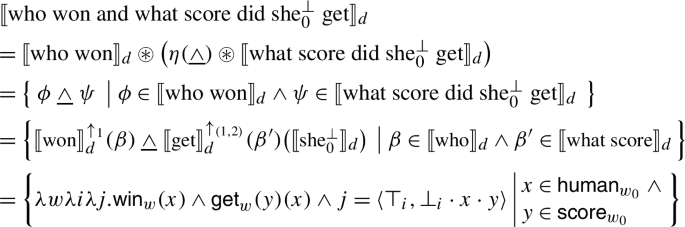

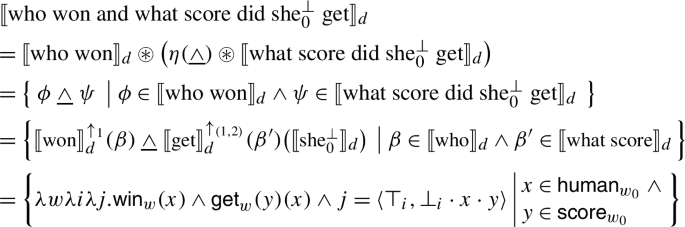

Appendix A: Formal analysis

The formal analysis given below demonstrates how the dynamic Hamblin semantics is compositionally built. Roughly speaking, I extend basic dynamic composition to an alternative-friendly dynamic composition in the same way in which Hamblin (1973), Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002), and Shimoyama (2006) upgrade basic compositional semantics to a compositional alternative semantics.

1.1 A.1 Types

Basic types Our basic types include individuals (type e), truth values (t ::= {0,1}), possible worlds (type s), and lists (type σ). Constructed types take one of the following forms, where a and b are any two types:

-

a→b, the type of a function from a-type elements to b-type elements;

-

{a}, the type of a set containing objects of type a;

-

a × b, the type of the pair consisting of an a-type element and a b-type element.

Type abbreviations For readability, I define the following type abbreviations:

-

, for dynamic propositions (a dynamic proposition is an intensional context change potential);

, for dynamic propositions (a dynamic proposition is an intensional context change potential); -

, for dynamic individuals or dynamic generalized quantifiers that have base type e, take scope over dynamic propositions of type

, for dynamic individuals or dynamic generalized quantifiers that have base type e, take scope over dynamic propositions of type  , and return dynamic propositions of type

, and return dynamic propositions of type  .

.

1.2 A.2 The basic dynamic fragment

Predicates

Nominals

A few notes:

-

An info-state consists of two lists. Which list is extended by a dref introducer depends on whether the dref introducer bears the primary focus or not.

-

Pronouns are double indexed: the superscript ⊥/⊤ determines which list in an info-state i is processed and the subscript determines which entity is picked out from that list. For instance, given an input info-state i, \([\!\![\text{she}_{0}^{\bot} ]\!\!]_{d}\) picks out the individual in the last position of the bottom list. Specifically, for every list l, \((l)_{n} :=\) the member stored in the |l| − 1 − n-th position of l. For example, given that l = [a0,b1,c2], \(l_{0}\) is c.

Sentential operator

Scope (Hendriks 1993)

-

(109)

-

(110)

Surface scope \(\big ( [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d}^{\uparrow _{1}} \big )^{\uparrow _{2}} = [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d}^{\uparrow _{(1, 2)}} = \lambda \beta \lambda \beta '. \beta ' (\lambda y. \beta (\lambda x. [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d} (x) (y) )) \)

-

(111)

Inverse scope \(\big ( [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d}^{\uparrow _{2}} \big )^{\uparrow _{1}} = [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d}^{\uparrow _{(2, 1)}} = \lambda \beta \lambda \beta '. \beta (\lambda x. \beta ' (\lambda y. [\!\![\text{saw} ]\!\!]_{d} (x) (y) )) \)

Derivation (basic case)

-

(112)

1.3 A.3 Composition of question meaning

Wh -expressions

Alternative-friendly composition

Derivation (basic case)Footnote 48

-

(113)

Derivation (conjoining wh-questions and cross-sentential anaphora to wh-expressions)

-

(114)

-

(115)

Discussion The essence of the composition proposed here is along the line of Hamblin (1973), Kratzer and Shimoyama (2002), and Shimoyama (2006). The original version of Hamblin semantics composes static meanings, which are trivially transformed into set denotations. Two alternative sets are composed via the pointwise functional application. In dynamic Hamblin semantics, any dynamic meaning can be mapped to the corresponding set denotation via the function η, and the pointwise functional application is embodied by the function ⊛. The present proposal illustrates an ‘in-situ’ approach to composition, i.e., wh-expressions do not take scope (cf. Karttunen 1977). Correspondingly, I use Hendriks’s proposal of scope taking, which does not require Quantifier Raising, to combine dynamic meanings. As a result, the two modes of composition are easily integrated with each other.Footnote 49

Appendix B: Comparison with Dekker’s (1993) Existential Disclosure

Existential Disclosure defined by Dekker (1993), written as

(the superscript d is short for ‘Dekker’), is based on the mechanism of dynamic binding. A concrete example is given in (121).

(the superscript d is short for ‘Dekker’), is based on the mechanism of dynamic binding. A concrete example is given in (121).

-

(116)

takes the meaning of A boy won and conjoins it with a dynamic proposition expressing an equation. \((\bot _{i})_{1-1}\) (= \((\bot _{i})_{0}\)) refers to the index 1 borne by the indefinite and picks up the dref introduced by that indefinite. y is a free variable. Then, we obtain a dynamic predicate by abstracting over y.

takes the meaning of A boy won and conjoins it with a dynamic proposition expressing an equation. \((\bot _{i})_{1-1}\) (= \((\bot _{i})_{0}\)) refers to the index 1 borne by the indefinite and picks up the dref introduced by that indefinite. y is a free variable. Then, we obtain a dynamic predicate by abstracting over y.

In fact,  can also be exploited to retrieve drefs introduced by wh-expressions. The definition of the

can also be exploited to retrieve drefs introduced by wh-expressions. The definition of the  operator is revised as in (122).

operator is revised as in (122).

-

(117)

′ retrieves drefs introduced by wh-expressions by referring to the indices of the wh-expressions. Suppose that there are n wh-expressions in the question. Each of them introduces a dref, which is added to the bottom list. Given the extended bottom list, the numbers in the set \(\{\ n - n' \mid n' \in \{1, ..., n\}\ \}\) indicate the positions on the list that store the relevant drefs. For concreteness, when a multiple-wh question has a single-pair reading (see Dayal 1996), each dynamic proposition in the set it denotes is associated with multiple drefs introduced by wh-expressions, as shown in (123).

′ retrieves drefs introduced by wh-expressions by referring to the indices of the wh-expressions. Suppose that there are n wh-expressions in the question. Each of them introduces a dref, which is added to the bottom list. Given the extended bottom list, the numbers in the set \(\{\ n - n' \mid n' \in \{1, ..., n\}\ \}\) indicate the positions on the list that store the relevant drefs. For concreteness, when a multiple-wh question has a single-pair reading (see Dayal 1996), each dynamic proposition in the set it denotes is associated with multiple drefs introduced by wh-expressions, as shown in (123).

-

(118)

\([\!\![\text{[which person]$_{1}$ ordered what$_{2}$} ]\!\!]_{d}\)

\(= \left \{\ \lambda w \lambda i \lambda j. \textsf {order}_{w} (y)(x) \wedge j = \langle \top _{i},\ \bot _{i} \cdot x \cdot y \rangle \ \left |\ \textsf {hmn}_{w_{0}} (x) \wedge \textsf {thg}_{w_{0}} (y)\ \right . \right \}\)

For each dynamic proposition in the set, the input bottom list is extended by adding two drefs x and y. That is, both wh-expressions introduce one dref in each dynamic proposition. In this case,  ′ can target the drefs x and y by referring to the number of the wh-expressions. Specifically, since we have two wh-expressions, \((\bot \cdot x \cdot y)_{2 - 2} = y\) and \((\bot \cdot x \cdot y)_{2 -1} = x\).

′ can target the drefs x and y by referring to the number of the wh-expressions. Specifically, since we have two wh-expressions, \((\bot \cdot x \cdot y)_{2 - 2} = y\) and \((\bot \cdot x \cdot y)_{2 -1} = x\).

However,  ′ is challenged when a multiple-wh question has a pair-list reading. In this case, each dynamic proposition in the question set has more newly added drefs than the number of wh-expressions. Recall the pair-list reading of which person ordered what in Sect. 6.3, repeated below.

′ is challenged when a multiple-wh question has a pair-list reading. In this case, each dynamic proposition in the question set has more newly added drefs than the number of wh-expressions. Recall the pair-list reading of which person ordered what in Sect. 6.3, repeated below.

-

(119)

In this example, the wh-question contains two wh-expressions, but each dynamic proposition in the resulting set involves four novel drefs. In the present analysis of the pair-list reading, how many drefs are introduced by wh-expressions depends on the size of the alternative set denoted by the subject wh-expression. In (124), this set contains two members, a and e, which are both correlated with a dref introduced by what. Therefore, the input bottom list is extended by adding two pairs consisting of a person and a dish. As a consequence,  ′ cannot target all the drefs introduced in (124) by simply referring to the two wh-expressions. In order to handle this problem, we have to assume a more complicated reference system. I leave this issue open for future study.

′ cannot target all the drefs introduced in (124) by simply referring to the two wh-expressions. In order to handle this problem, we have to assume a more complicated reference system. I leave this issue open for future study.

By contrast,  , defined in Sect. 4.3, is built on

, defined in Sect. 4.3, is built on  , which uses subtraction of lists to generate a list that contains only novel drefs. This derivational process does not refer to the drefs introduced by wh-expressions and hence does not run into the same problem as

, which uses subtraction of lists to generate a list that contains only novel drefs. This derivational process does not refer to the drefs introduced by wh-expressions and hence does not run into the same problem as  .

.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H. Mandarin wh-conditionals: A dynamic question approach. Nat Lang Semantics 29, 401–451 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-021-09180-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-021-09180-4

is bound by shěnme, even though it is not in the syntactic scope of the latter. Therefore, this binding relation is a dynamic one. It calls for a dynamic semantics of wh-expressions. I will return to this issue in Sect.

is bound by shěnme, even though it is not in the syntactic scope of the latter. Therefore, this binding relation is a dynamic one. It calls for a dynamic semantics of wh-expressions. I will return to this issue in Sect.

eat?

eat? to the existential sentence A girl won results in a dynamic predicate, as in (i). As a result,

to the existential sentence A girl won results in a dynamic predicate, as in (i). As a result,  seems to wipe out the existential operator (this is the reason why this operation is dubbed Existential Disclosure).

seems to wipe out the existential operator (this is the reason why this operation is dubbed Existential Disclosure).

and become variables. If the novelty condition does not apply to wh-expressions, these variables can be bound by one operator.

and become variables. If the novelty condition does not apply to wh-expressions, these variables can be bound by one operator.

to the wh-clauses.

to the wh-clauses.

is contextually determined, as Kratzer (

is contextually determined, as Kratzer (

′ encodes the choice function, x is just one place that sells wine in s. Quantifying over situation–entity pairs (x,s) is equivalent to quantifying over situations s such that s associates with a certain liquor store x in s, not all liquor stores in s. Therefore, (ii) indicates that in most situations the speaker will go to one liquor store.

′ encodes the choice function, x is just one place that sells wine in s. Quantifying over situation–entity pairs (x,s) is equivalent to quantifying over situations s such that s associates with a certain liquor store x in s, not all liquor stores in s. Therefore, (ii) indicates that in most situations the speaker will go to one liquor store. , for dynamic propositions (a dynamic proposition is an intensional context change potential);

, for dynamic propositions (a dynamic proposition is an intensional context change potential); , for dynamic individuals or dynamic generalized quantifiers that have base type e, take scope over dynamic propositions of type

, for dynamic individuals or dynamic generalized quantifiers that have base type e, take scope over dynamic propositions of type  , and return dynamic propositions of type

, and return dynamic propositions of type  .

.