Abstract

Gambling is widely considered a socially acceptable form of recreation. However, for a small minority of individuals, it can become both addictive and problematic with severe adverse consequences. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to provide an overview of prevalence studies published between 2016 and the first quarter of 2022 and an updated estimate of problem gambling in the general adult population. A systematic review and a meta-analysis were carried out using academic databases, Internet, and governmental websites. Following this search and utilizing exclusion criteria, 23 studies on adult gambling prevalence were identified, distinguishing between moderate risk/at risk gambling and problem/pathological gambling. This study found a prevalence of moderate risk/at risk gambling to be 2.43% and of problem/pathological gambling to be 1.29% in the adult population. As difficult as it may be to compare studies due to different methodological procedures, cutoffs, and time frames, the present meta-analysis highlights the variations of prevalence across different countries, giving due consideration to the differences between levels of risk and severity. This work intends to provide a starting point for policymakers and academics to fill the gaps on gambling research—more specifically in some countries where the lack of research in this field is evident—and to study the effectiveness of policies implemented to mitigate gambling harm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Allami, Y., Hodgins, D. C., Young, M., Brunelle, N., Currie, S., Dufour, M., Flores-Pajot, M., & Nadeau, L. (2021). A meta-analysis of problem gambling risk factors in the general adult population. Addiction, 116(11), 2968–2977. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15449

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

Assanangkornchai, S., McNeil, E. B., Tantirangsee, N., Kittirattanapaiboon, P., Thai National Mental Health Survey Team. (2016). Gambling disorders, gambling type preferences, and psychiatric comorbidity among the Thai general population: Results of the 2013 National Mental Health Survey. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.066

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G., & Schwarzer, G. (2019). How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 22, 153–160.

Barbaranelli, C., Vecchione, M., Fida, R., & Podio-Guidugli, S. (2013). Estimating the prevalence of adult problem gambling in Italy with SOGS and PGSI. Journal of Gambling Issues, 28, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2013.28.3

Bijker, R., Booth, N., Merkouris, S. S., Dowling, N. A., & Rodda, S. N. (2022). Global prevalence of help-seeking for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15952

Bilevicius, E., Edgerton, J. D., Sanscartier, M. D., Jiang, D., & Keough, M. T. (2020). Examining gambling activity subtypes over time in a large sample of young adults. Addiction Research and Theory, 28(4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2019.1647177

Brunborg, G. S., Hanss, D., Mentzoni, R. A., Molde, H., & Pallesen, S. (2016). Problem gambling and the five-factor model of personality: A large population-based study: Personality and gambling problems. Addiction, 111(8), 1428–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13388

Butler, N., Quigg, Z., Bates, R., Sayle, M., & Ewart, H. (2018). Isle of man gambling survey 2017: Prevalence, methods, attitudes. Publich Health Institute.

Calado, F., & Griffiths, M. D. (2016). Problem gambling worldwide: An update and systematic review of empirical research (2000–2015). Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 592–613. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.073

Chóliz, M., Marcos, M., & Lázaro-Mateo, J. (2021). The risk of online gambling: A study of gambling disorder prevalence rates in Spain. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19(2), 404–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00067-4

Cochran, W. G. (1950). The comparison of percentages in matched samples. Biometrika, 37(3/4), 256–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/2332378

Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). Wiley.

Colasante, E., Gori, M., Bastiani, L., Siciliano, V., Giordani, P., Grassi, M., & Molinaro, S. (2013). An assessment of the psychometric properties of Italian version of CPGI. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(4), 765–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9331-z

Cosgrave, J. (2022). Gambling ain’t what it used to be: The instrumentalization of gambling and late modern culture. Critical Gambling Studies, 3(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.29173/cgs81

Dowling, N. A., Youssef, G. J., Jackson, A. C., Pennay, D. W., Francis, K. L., Pennay, A., & Lubman, D. I. (2016). National estimates of Australian gambling prevalence: Findings from a dual-frame omnibus survey: Australian dual-frame gambling survey. Addiction, 111(3), 420–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13176

Dowling, N. A., Merkouris, S. S., Greenwood, C. J., Oldenhof, E., Toumbourou, J. W., & Youssef, G. J. (2017). Early risk and protective factors for problem gambling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.008

Dunne, S., Flynn, C., & Sholdis, J. (2017). 2016 Northern Ireland gambling prevalence survey. Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency.

Economou, M., Souliotis, K., Malliori, M., Peppou, L. E., Kontoangelos, K., Lazaratou, H., Anagnostopoulos, D., Golna, C., Dimitriadis, G., Papadimitriou, G., & Papageorgiou, C. (2019). Problem gambling in Greece: Prevalence and risk factors during the financial crisis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(4), 1193–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09843-2

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian problem gambling index: Final report. Ottawa Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Gambling Commission. (2018). Participation in gambling and rates of problem gambling—Scotland 2017. Gambling Commission.

Gambling Commission. (2019). Gambling behaviour in Wales: Findings from the welsh problem gambling survey 2018. NHS Digital.

Grant, J. E., Potenza, M. N., Weinstein, A., & Gorelick, D. A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.491884

Harrison, G. W., Jessen, L. J., Lau, M. I., & Ross, D. (2018). Disordered gambling prevalence: Methodological innovations in a general Danish population survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(1), 225–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9707-1

Hodgins, D. C., & El-Guebaly, N. (2000). Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: A comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction, 95(5), 777–789. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95577713.x

Hunter, J. P., Saratzis, A., Sutton, A. J., Boucher, R. H., Sayers, R. D., & Bown, M. J. (2014). In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(8), 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003

Johansson, A., Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., Odlaug, B. L., & Götestam, K. G. (2009). Risk factors for problematic gambling: A critical literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-008-9088-6

Lesieur, H., & Blume, S. (1987). The South Oaks gambling screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 144, 1184–1188. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184

Massatti, R. R., Starr, S., Frohnapfel-Hasson, S., & Martt, N. (2017). A baseline study of past-year problem gambling prevalence among Ohioans. Journal of Gambling Issues. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2016.34.3

Merkouris, S., Greenwood, C., Manning, V., Oakes, J., Rodda, S., Lubman, D., & Dowling, N. (2020). Enhancing the utility of the problem gambling severity index in clinical settings: Identifying refined categories within the problem gambling category. Addictive Behaviors, 103, 106257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106257

Minutillo, A., Mastrobattista, L., Pichini, S., Pacifici, R., Genetti, B., Vian, P., Andreotti, A., & Mortali, C. (2021). Gambling prevalence in Italy: Main findings on epidemiological study in the Italian population aged 18 and over. Minerva Forensic Medicine. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2784-8922.21.01805-7

Mongan, D., Millar, S. R., Doyle, A., Chakraborty, S., & Galvin, B. (2022). Gambling in the Republic of Ireland results from the 2019–20 National Drug and Alcohol Survey. Health Research Board.

Mori, T., & Goto, R. (2020). Prevalence of problem gambling among Japanese adults. International Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2020.1713852

Neal, P., Del-fabbro, P. H., & O’Neill, M. (2005). Problem gambling and harm towards a national definition. Final report. Gambling Research Australia.

Nelson, S. E., Gebauer, L., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2009). Gambling problem symptom patterns and stability across individual and timeframe. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 523–533. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016053

Park, K. H., & Losch, M. E. (2019). A prevalence of gambling attitudes and behaviors: A 2018 survey of adult Iowans. Iowa Department of Public Health Protecting and Improving the Health of Iowans.

Petry, N. M., & O’Brien, C. P. (2013). Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction, 108(7), 1186–1187. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12162

Raylu, N., & Oei, T. P. S. (2002). Pathological gambling. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(7), 1009–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00101-0

Sagoe, D., Griffiths, M. D., Erevik, E. K., Høyland, T., Leino, T., Lande, I. A., Sigurdsson, M. E., & Pallesen, S. (2021). Internet-based treatment of gambling problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10(3), 546–565. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00062

Schellinck, T., Schrans, T., Schellinck, H., & Bliemel, M. (2015). Instrument development for the focal adult gambling screen (FLAGS-EGM): A measurement of risk and problem gambling associated with electronic gambling machines. Journal of Gambling Issues, 30, 174. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2015.30.8

Shaffer, H. J., Hall, M. N., & Vander Bilt, J. (1999). Estimating the prevalence of disordered gambling behavior in the United States and Canada: A research synthesis. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1369–1376.

Stevens, M. (2017). 2015 Northern territory gambling prevalence and wellbeing survey report. Berlin: Northern Territory Government.

Suurvali, H., Hodgins, D., Toneatto, T., & Cunningham, J. (2008). Treatment seeking among Ontario problem gamblers: Results of a population survey. Psychiatric Services, 59(11), 1343–1346. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.11.1343

Suvarnapathaki, S. (2021). Meta-analysis of prevalence studies using R. International Journal of Scientific Research, 10(8), 74–77. https://doi.org/10.36106/ijsr

Costes, J.-M., Richard, J.-B., Eroukmanoff, V., Le Nézet, O., & Philippon, A. (2020). Les Francais et les jeux d’argent et de hasard Résultats du Baromètre de Santé publique France 2019. Observatoire français des drogues et des toxicomanies.

Gerstein, D., Murphy, S., Toce, M., Volberg, R., Harwood, H., Tucker, A., Christiansen, E., Cummings, W., & Sinclair, S. (1999). Gambling impact and behavior study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission.

Gisle, L., & Drieskens, S. (2019). Pratique des jeux de hasard et d’argent. Bruxelles, Belgique: Sciensano. Numéro de rapport: D/2019/14.440/69. HIS 2018.

Meyer, G., Hayer, T., & Griffiths, M. (Eds.). (2009). Problem gambling in Europe: Challenges, prevention, and interventions. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09486-1

NHS Digital. (2019). Health Survey for England 2018—Supplementary analysis on gambling.

Nower, L., Volberg, R., & Caler, K. R. (2017). The prevalence of online and land‐based gambling in New Jersey. Report to the New Jersey Division of Gaming Enforcement.

RStudio Team. (2022). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC. http://www.rstudio.com/

Salonen, A., Hagfors, H., Lind, K., & Jukka, K. (2020). Gambling and problem gambling—Finnish Gambling 2019. Statistical Report THL.

Tracy, J. K., Maranda, L., & Scheele, C. (2018). Statewide gambling prevalence in Maryland: 2017. https://doi.org/10.11575/PRISM/36127

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends [Technical Report]. Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. https://opus.uleth.ca/handle/10133/3068

Woods, A., Sproston, K., Brook, K., Delfabbro, P., & O’Neil, M. (2019). Gambling prevalence in South Australia (2018): Final report (South Australia) [Report]. Department of Human Services (SA). https://apo.org.au/node/237946

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Although this article is the result of a common reflection among the authors, Introduction and Discussion are attributable to FL, Methods and Conclusion are attributable to MEG, Results are attributable to EG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

No ethical approval was needed because data from previous published studies in which informed consent was obtained by primary investigators were retrieved and analyzed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

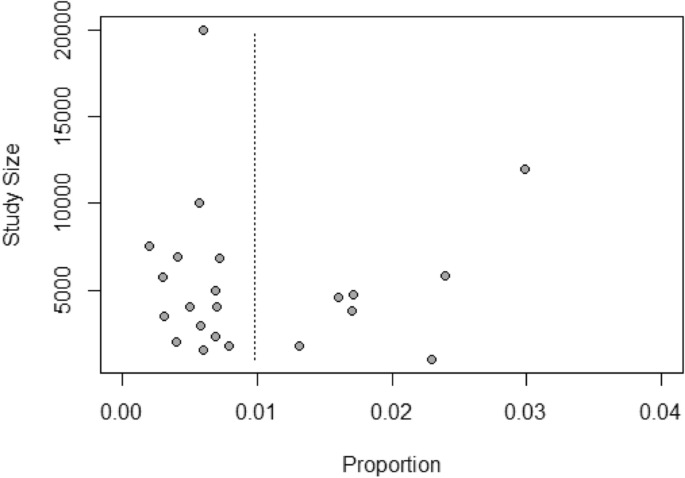

Appendix 1

Funnel Plots

To assess publication bias, funnel plots were created for the prevalence estimates. As Hunter et al. (2014) recommended for meta-analyses of proportions, sample size (study size) was employed as measure of accuracy on the y-axis.

Funnel plots suggest a certain asymmetry, mainly due to the consistent heterogeneity characterizing the studies, both for cultural, socio-economic issues related to each national/territorial reality, and for reasons related to the different types of sampling, different methods of administration and screening instruments used (Figs. 6, 7 and 8).

Funnel plot—estimates of problem/pathological gambling without the Mori and Goto study (Japan, 2020)

Appendix 2

Meta-regression and Subgroup Analyses

A series of subgroup analyses using a random effects model were performed to investigate possible factors explaining the variability in meta-analytic estimates. First, a meta-regression was conducted to test the overall effect of the following moderators on the mean effect size:

-

I.

origin (European vs. non-European)

-

II.

screening instrument (PGSI/CPGI vs other instruments

-

III.

interview method (telephone interview—CATI or other types; online survey; face-to-face survey—CAPI or other types).

The results of this technique are reported in the table below.

mixed-effect meta-regression—problem/pathological gambling | |

Estimate | |

intrcpt | − 3.8957 |

metadefPG$OriginNon-European | − 0.3362 |

metadefPG$MeasurePGSI | − 1.2402 |

metadefPG$MethodOnline survey | 0.7018 |

metadefPG$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 0.4512 |

Standard error | |

intrcpt | 0.5276 |

metadefPG$OriginNon-European | 0.5017 |

metadefPG$MeasurePGSI | 0.5400 |

metadefPG$MethodOnline survey | 0.4996 |

metadefPG$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 0.5028 |

p value | |

intrcpt | < 0.0001 |

metadefPG$OriginNon-European | 0.5028 |

metadefPG$MeasurePGSI | 0.0216 |

metadefPG$MethodOnline survey | 0.1601 |

metadefPG$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 0.3696 |

mixed-effect meta-regression—at-risk/moderate risk gambling | |

Estimate | |

intrcpt | − 3.8019 |

metadefRISK$OriginNon-European | − 0.5275 |

metadefRISK$MeasurePGSI | − 0.7642 |

metadefRISK$MethodOnline survey | 0.9893 |

metadefRISK$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 1.1865 |

Standard error | |

intrcpt | 0.7892 |

metadefRISK$OriginNon-European | 0.5609 |

metadefRISK$MeasurePGSI | 0.7267 |

metadefRISK$MethodOnline survey | 0.5317 |

metadefRISK$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 0.5292 |

p value | |

intrcpt | < 0.0001 |

metadefRISK$OriginNon-European | 0.3470 |

metadefRISK$MeasurePGSI | 0.2930 |

metadefRISK$MethodOnline survey | 0.0628 |

metadefRISK$MethodTelephone interview (CATI or other types) | 0.0250 |

Regarding problem/pathological gambling, the meta-regression did not yield a significant association for the Origin (p = 0.5028) and for the Method (p = 0.1601; 0.3696). Concerning moderate risk/at-risk gambling, meta-regression showed no significant association for Origin (p = 0.3470) and Measure (p = 0.2930).

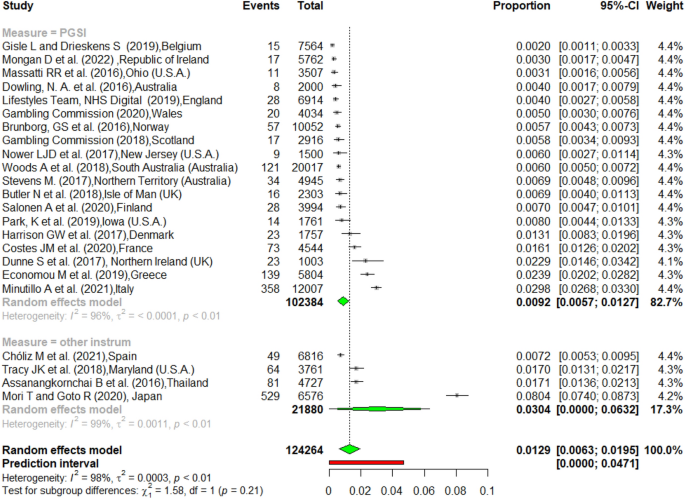

Below are the analyses for the categories that have yielded a significant association according to the meta-regression: the subgroup analysis by screening instrument for problem/pathological gambling (Fig. 9) and the subgroup analysis by interview method for moderate risk/at-risk gambling (Fig. 10).

The subgroup analysis by screening instrument provides strong evidence of variation. The pooled estimate derived from the PGSI (0.92%; 95% CI 0.57; 1.27) turns out to be significantly lower compared to that of studies employing other screening tools (DSM-IV, SOGS, NODS) (3.04%; 95% CI 0.00; 6.32). This difference can be mainly due to the very high estimate obtained in the study conducted in Japan. There were high levels of between-study heterogeneity in each of these subgroups (I2 Measure = PGSI: 96.1% and I2 Measure = other instruments: 99.3%).

The subgroup analysis by interview method involves three subgroups: telephone interview (CATI or other types), online survey and face-to-face survey (CAPI or other types). Substantial variations are observed depending on the interview method. In particular, the pooled prevalence of the studies involving face-to-face interview is of a considerably lower magnitude (1.53%; 95% CI 0.40–2.66) compared with the other two interview modes. Studies using online surveys have a value almost twice as high (3.20%; 95% CI 1.45–4.95) compared to face-to-face interviews, while studies using telephone interviews have a high estimate in a middle position between the two modes (2.78%, 95% CI 1.90–3.67). High levels of heterogeneity between studies were also found in each of these subgroups (I2 Method = Telephone interview 96.6%; I2 Method = Online survey: 97.8%; I2 Method = Face-to-face survey: 98.5%).

Below are the analyses for subgroups whose effect was not significant according to the meta-regression (Figs. 11,12 and 13).

First, when looking at the world region dichotomy (e.g. European/Non-European prevalence study variable), a higher pooled estimate of the non-European countries (1.64%, 95% CI 0.06; 3.23) is noted compared to the lower result of the European studies (1.06%, 95% CI 0.60; 1.52) (Fig. 11).

There is also statistically significant variation on the interview modes. Specifically, the pooled estimate of the studies that used online survey as the method of collection stands out (2.65, 95% CI 0.00; 6.17) (Fig. 12).

There was no evidence of systematic variation in the prevalence estimates by origin. An analysis for the moderator method was not performed because in the case of moderate risk and at risk gambling estimates, only two studies employing instruments other than PGSI are available.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gabellini, E., Lucchini, F. & Gattoni, M.E. Prevalence of Problem Gambling: A Meta-analysis of Recent Empirical Research (2016–2022). J Gambl Stud 39, 1027–1057 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10180-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-022-10180-0