Abstract

In this paper, we study to what extent a movie’s box-office receipts are affected by the temporal distribution of rival films. We propose a reduced-form empirical model to measure and test competition effects among films released close to each other in a standard regression framework. Such an analysis is appealing in terms of its policy implication and may provide guidance to distributors to decide on their releasing dates of their firms. We estimate this model using information on the films released in five countries: the USA, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Spain. The geographical dimension of our data set permits us to control for unobserved heterogeneity among films released using panel data techniques, which allows us to evaluate the individual and specific effects of each film. Thus we deal with one of the most relevant features of the movie market, namely the presence of highly differentiated products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

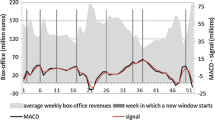

Einav (2007) found that the underlying seasonality of box-office revenues is amplified by the seasonality in the number and quality of available movies. However, as the underlying demand accounts for about two-thirds of the observed seasonal variation in total sales, we will try to control for this underlying seasonality in our empirical application.

For instance, a good performance during the first weekend might create a positive word-of-mouth effect, capturing the attention of the public, media and exhibitors (De Vany 2004).

We can observe some price discrimination, but this is in terms of days, seasons or consumer groups, not among movies. The exception is the case of 3-D movies, but these can be considered as a different commodity.

However, Basuroy et al. (2006) have found that ongoing films’ competition for screens has a positive effect on weekly box-office receipts and screen coverage.

For more details, see the theoretical model developed in Gutiérrez-Navratil et al. (2011).

Due to data limitations, the market share in France has been computed using total attendance instead of total box-office revenues.

We focus our analysis on the most potentially harmful rival films, those released during the period from 3 weeks before to 3 weeks after movie i’s release.

We just used three categories since we had to harmonize rating scales that differ across countries. The general audience group includes films suitable for all age groups and for children over 6 years (G and PG rating). The restricted audience group includes films more suitable for ages over 17 years (R rating) and the teenager audiences group includes films suitable for teenagers (PG-13).

We use an F test to test whether the film-specific constant terms (α i ) are all equal. We obtain a value of 5.23, which far exceeds any critical value of an F(2810, 9030). Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the individual effects model.

The value for the F(16, 2810) statistic is 115.64, above any critical value, so we strongly reject the null hypothesis that the individual effects and explanatory variables are uncorrelated.

References

Ainslie, A., Dreze, X., & Zufryden, F. (2005). Modeling movie life cycles and market share. Marketing Science, 24(3), 508–517. doi:10.1287/mksc.1040.0106.

Basuroy, S., Desai, K. K., & Talukdar, D. (2006). An empirical investigation of signaling in the motion picture industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(2), 287–295. doi:10.1509/jmkr.43.2.287.

Calantone, R. J., Yeniyurt, S., Townsend, J. D., & Schmidt, J. B. (2010). The effects of competition in short product life-cycle markets: The case of motion pictures. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(3), 349–361. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00721.x.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics using Stata. Texas: Stata Press.

Chisholm, D., & Norman, G. (2012). Spatial competition and market share: An application to motion pictures. Journal of Cultural Economics, 36(3), 207–225.

Corts, K. S. (2001). The strategic effects of vertical market structure: Common agency and divisionalization in the US motion picture industry. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 10(4), 509–528. doi:10.1162/105864001753356088.

Davis, P. (2006). Spatial competition in retail markets: Movie theaters. The Rand Journal of Economics, 37(4), 964–982.

De Vany, A. S. (2004). Hollywood economics: How extreme uncertainty shapes the film industry contemporary political economy series. Routledge: Taylor & Francis.

Einav, L. (2007). Seasonality in the U.S. motion picture industry. The Rand Journal of Economics, 38(1), 127–145.

Elberse, A., & Eliashberg, J. (2003). Demand and supply dynamics for sequentially released products in international markets: The case of motion pictures. Marketing Science, 22(3), 329–354. doi:10.1287/mksc.22.3.329.17740.

Ginsburgh, V., & Weyers, S. (1999). On the perceived quality of movies. Journal of Cultural Economics, 23(4), 269–283. doi:10.1023/a:1007596132711.

Gutiérrez-Navratil, F., Fernández-Blanco, V., Orea, L., & Prieto-Rodriguez, J. (2011). How do your rivals’ releasing dates affect your box office? ACEI Working Paper Series. AWP-4-2011, the Association for Cultural Economics International.

Hadida, A. L. (2009). Motion picture performance: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(3), 297–335. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00240.x.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Houston, M. B., & Walsh, G. (2006). The differing roles of success drivers across sequential channels: An application to the motion picture industry. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 559–575. doi:10.1177/0092070306286935.

Jedidi, K., Krider, R., & Weinberg, C. (1998). Clustering at the movies. Marketing Letters, 9(4), 393–405. doi:10.1023/a:1008097702571.

Kanzler, M. (2011). The European Cinema Markets 2010 in Figures. European Audiovisual Observatory. Presentation in the framework of the 17th edition of the Sarajevo Film Festival. http://www.obs.coe.int/online_publication/expert/europeancinemamarkets2010.pdf.en.

Krider, R. E., Li, T., Liu, Y., & Weinberg, C. B. (2005). The lead-lag puzzle of demand and distribution: A graphical method applied to movies. Marketing Science, 24(4), 635–645. doi:10.1287/mksc.1050.0149.

Krider, R. E., & Weinberg, C. B. (1998). Competitive dynamics and the introduction of new products: The motion picture timing game. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(1), 1–15.

Lang, D. M., Switzer, D. M., & Swartz, B. J. (2011). DVD sales and the R-rating puzzle. Journal of Cultural Economics, 35(4), 267–286.

McKenzie, J. (2010). How do theatrical box office revenues affect DVD retail sales? Australian empirical evidence. Journal of Cultural Economics, 34(3), 159–179.

McKenzie, J. (2012). The economics of movies: A literature survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(1), 42–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6419.2010.00626.x.

Moul, C. C., & Shugan, S. M. (2005). Theatrical release and the launching of motion pictures. In C. C. Moul (Ed.), A concise handbook of movie industry economics (pp. 80–137). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neelamegham, R. & Chintagunta, P. (1999). A Bayesian model to forecast new product performance in domestic and international markets. Marketing Science, 18(2), 115–136.

Orbach, B. Y., & Einav, L. (2007). Uniform prices for differentiated goods: The case of the movie-theater industry. International Review of Law and Economics, 27(2), 129–153. doi:10.1016/j.irle.2007.06.002.

Radas, S., & Shugan, S. M. (1998). Seasonal marketing and timing new product introductions. Journal of Marketing Research, 35(3), 296–315.

Ravid, S. A. (1999). Information, blockbusters, and stars: A study of the film industry. Journal of Business, 72(4), 463–492.

Sochay, S. (1994). Predicting the performance of motion pictures. Journal of Media Economics, 7(4), 1–20.

Sunada, M. (2012). Competition among movie theaters: An empirical investigation of the Toho–Subaru antitrust case. Journal of Cultural Economics, 36(3), 179–206.

Verbeek, M. (2008). A guide to modern econometrics (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Vogel, H. L. (2007). Entertainment industry economics. A guide for financial analysis (7th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded with support from: the Department of Education, Universities and Research of the Basque Government; the European Commission (EU Culture Programme project #2012-0298/001); the Government of Spain (projects #ECO2011-27896, #ECO2010-17590 and #ECO2010-17240). It reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gutierrez-Navratil, F., Fernandez-Blanco, V., Orea, L. et al. How do your rivals’ releasing dates affect your box office?. J Cult Econ 38, 71–84 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9188-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-012-9188-0

Keywords

- Temporal competition

- Movie exhibition

- Film industry

- Panel data

- Unobserved heterogeneity

- Differentiated products