Abstract

This paper compares bank regulation and supervision in Japan and Germany. We consider these countries because they both have bank-dominated financial systems and their banking systems are often lumped together as one model, yet, bank stability differs significantly. We show that Japan and Germany have chosen different approaches to bank regulation and supervision and ask why they made their choices. We argue that bank regulation and supervision were less efficient in Japan than in Germany and that these differences were decisive for bank behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Case studies involve data collections through personal interviews, verbal or written reports, or observations; they are holistic, allow for contextuality, take a longitudinal approach and are particularily well suited in cross-cultural settings (Ghauri 2004). For overviews over the case study approach and different qualitative research methods see Yin (2003), Gerring (2004) and the contributions in Marschan-Piekkari and Welch (2004).

During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Japan first tried to adopt French Criminal and Civil Codes because France, at that time, was viewed as having the most sophisticated legal system. With the adoption of a constitution patterned after the Prussian constitution in 1889, however, German influences gained in importance and, in 1899, Japan adopted a German-style civil Code. For details see Luney (1989). On the relevance of the German state as a constitutional model for Meiji Japan see also Lehmbruch (1997).

In 2006, Germany was ranked 16th, Japan was ranked 17th in the Transparency International Corruption Index. See http://www.transparancy.org. Of course, there are still cultural and religious differences between both countries.

Though Germany belongs to the European Monetary Union (EMU), bank regulation and supervision still resides in the individual countries; see Barth et al. (2006).

Since 1970, there were 117 banking crises in 93 countries and 51 non-systemic runs in 45 countries (Caprio and Klingebiel 2003).

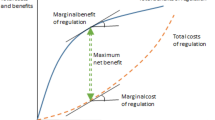

There are other externalities even when no bank run occurs. They arise because of dysfunctional bank-internal capital markets (Dietrich and Vollmer 2006), inefficient cross-subsidization between borrowers (Jakivuolle and Vesala 2007) and implied disincentives for bank-financed firms (Dietrich and Hauck 2007). In addition to these externalities associated with the specifics of the banking business, there are other potential reasons for regulating banks. From political economy view, e.g., there may be political capture, while industrial economics teaches to control market power.

Much of the information presented in the following sections stems from Barth et al. (2006) and from personal interviews with representatives of the respective institutions and from their websites. See http://www.fsa.go.jp; http://www.dic.go.jp; http://www.bundesbank.de and http://www.bafin.de.

For a study that exemplifies the history of Japanese banks using the case of Mitsui Bank see Ogura (2002).

As for BoJ, this measure was legitimated as being part of its LLR function which included not only liquidity support but also risk capital provision (Hatakeda 2007). The new bank (“Tōkyō Kyōdō Bank”) was later reorganized into a “bad bank” or “bridge bank”, the Resolution and Collection Bank (RCB), which was designed as the general assuming bank for failed credit cooperatives. In 1999, RCB was reorganized into the Resolution and Collection Corporation (RCC) which was given the capability to purchase bad loans from banks (Nakaso 2001; Hori 2005).

“Law Regarding Emergency Measures for Financial Stabilization”. According to Hori (2005), the provision of public funds to financial institutions before their failure was heavily critizised by opposition parties in the Japanese Parliament (Diet).

These measures were part of the “big bang” reforms initiated by Prime Minister Hashimoto which started with the elimination of foreign exchange controls and included the revision of the Bank of Japan Law which provided BoJ more formal independence from MoE. See Cargill (2001); Ito and Melvin (2001). The Hashimoto reforms applied some “New Public Management” principles to Japan`s central government, namely policy evaluation for ministries and agencification as a means of decentralization. See Yamamoto (2003).

For details on the establishment of FSA see Hori (2005, pp. 121–126).

The Cabinet Office has been created following the Hashimoto reforms to facilitate inner government policy co-ordination efforts (this information is owed to one referee).

For the following information see the annual reports of DIJC.

In the two years from April 2003 to the end of March 2005, the full amount for current deposits, ordinary deposits, and specified deposits was fully protected.

“Law concerning Emergency Measures for the Reconstruction of the Functions of the Financial System”; the law allowed a replacement of the management and a cleaning-up of the balance sheet. The first case was the failure of Long-term Credit Bank of Japan, which was nationalized in October 1998.

The threat to be expelled from BoJ’s current account services became very effective since the beginning of the Quantitative Easing Policy in March 2001. According to Baba et al. (2005, p. 16), all financial institutions in Japan became heavily dependent on BoJ’s open market operations because the uncollateralized interbank market has almost collapsed due to low interest rates that did not even cover trading costs. In the meantime, however, the interbank market has recovered.

The Bundesamt was the regulatory authority only for the banking industry; in addition, there were separate regulatory agencies for insurances and security firms.

Members of schemes safeguarding the viability of institutions, i.e., cooperative banks and savings banks, are exempted from compulsory membership in a statutory compensation scheme (Deutsche Bundesbank 2000a).

Though beeing a separate agency, FSA seems to be independet from governmental directives; see the cases reported in The Japan Times Online (2001); Mulgan (2002) or Negishi (2003). While prior to the reforms MOF was the sole decision making authority, under the new regulatory framework, the “decline in the influence of the Ministry of Finance is offset by an increase in the influence of politicians”, Cargill (2001, p. 159).

Commercial banks sometimes complain high costs and demand that BaFin’s operational costs are borne by the Government, these demands were rejected by the Minister of Finance; see Handelsblatt (2006). The International Monetary Fund (2003b) on the other hand notes concerns that the interests of supervised institutions receive too much weight on the Board (10 out of 21 members are from supervised institutions).

The existing division of labor between BaFin and Bundesbank is currently a matter of a political debate, especially between the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Economic Affairs. While the former wants to strengthen BaFin’s position, the latter prefers a stronger role of Deutsche Bundesbank in supervision; a stronger role of Bundesbank is also demanded by the Council of Economic Advisers (see SVR 2007).

As reported by Beck (2002), problems with SMH-Bank were discovered in the 1980s by the BdB; these problems, however, remained undetected by supervisory offices.

See Gilbert (1992) for a comparison between both methods; whether P&A is less costly than liquidation depends on the premium paid by the assuming bank.

In the case of the recent failure of ‘Privatbank Reithinger’, BaFin in September 2006 declared that this bank was not able anymore to pay out depositors; they were informed and paid out by the deposit insurance scheme of the BdB. For details see the webpage of BdB: http://www.bankenverband.de/channel/101832/art/1836/index.html.

Only the cooperative banking sector maintains such a private resolution company called “Bankaktiengesellschaft Hamm”, which resulted from a failure of a cooperative bank in 1984. In 2003, there was some public discussion to establish a public “bad bank” in Germany but this plan was rejected (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2003). Instead, commercial banks increasingly use credit derivatives to hedge risk, especially credit default swaps (see Deutsche Bundesbank 2004a, b).

Most of these studies use the option-pricing model (Merton 1977) that considers deposit insurance as a put option on the bank’ assets.

A regulatory forbearance parameter of ρ = 0.97 (ρ = 1.00) assumes that the book value of a bank’s assets can fall to 97% (100%) of the bank’s debt before the bank is closed by regulators.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2002). Reversal of fortune. Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1231–1294.

Acharya, S., & Dreyfus, J.-F. (1989). Optimal bank reorganization policies and the pricing of federal deposit insurance. Journal of Finance, 44, 1313–1333.

Allen, F. (1990). The market for information and the origin of financial intermediation. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 1, 3–30.

Allen, F., & Gale, D. (2000). Financial contagion. Journal of Political Economy, 108, 1–33.

Allen, L., & Saunders, A. (1993). Forbearance and valuation of deposit insurance as a callable put. Journal of Banking and Finance, 17, 629–643.

Amaya, T. (2008). Saikin no kinyuu kensa no ugoki (Movements of recent financing examinations). Kinyuu journalu (Financial Journal; in Japanese), 6, 45–48.

Aoki, M., Patrick, H., & Sheard, P. (1994). The Japanese main bank system: An introductory overview. In M. Aoki & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system. Its relevance for develo** and transforming economies (pp. 1–50). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Avery, R. B., Belton, T. M., & Goldberg, M. A. (1988). Market discipline in regulating bank risk: New evidence from capital markets. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 20, 597–610.

Baba, N., Nishioka, S., Oda, N., Shirakawa, M., Ueda, K., Ugai, H., et al. (2005). Japan’s deflation, problems in the financial system and monetary policy. BIS Working paper No 188, Basel, November.

Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behaviour. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 797–817.

Barth, J. R., Caprio, G., Jr., & Levine, R. (2004a). Bank regulation and supervision: What works best? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 13, 205–248.

Barth, J. R., Caprio, G., Jr., & Levine, R. (2006). Rethinking bank regulation. Till angels govern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barth, J. R., Koepp, R., Zhou, Z., et al. (2004). Banking reform in China: Catalyzing the nation’s financial future. Santa Monica: mimeo.

Baums, T. (1994). The German banking system and its impact on corporate finance and governance. In M. Aoki & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system. Its relevance for develo** and transforming economies (pp. 409–449). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beck, T. (2002). Deposit insurance as a private club: Is Germany a model? The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 42, 701–719.

Beck, T., & Levine, R. (2003). Legal institutions and financial development. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 3136, Washington.

Beck, T., Levine, R., & Loayza, N. (2000). Finance and the sources of growth. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 261–300.

Bencivenga, V. T., & Smith, B. D. (1991). Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 195–209.

Bhattacharya, S., Boot, A. W. A., & Thakor, A. V. (1998). The economics of bank regulation. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 30, 745–770.

Bhattacharya, S., & Thakor, A. V. (1993). Contemporary banking theory. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 3, 2–50.

Blum, J. (2007). Why ‘Basel II’ may need a leverage ratio restriction. Zurich, mimeo: Swiss National Bank.

Born, K. E. (1967). Die deutsche Bankenkrise 1931. Finanzen und Politik (The German banking crisis 1931. Finance and politics). München: Piper.

Bryant, R. (1980). A model of reserves, bank runs and deposit insurance. Journal of Banking and Finance, 4, 335–344.

Bundesminister der Finanzen. (2007). Eckpunkte zur Reorganisation der Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht, Pressemitteilung vom 22.05.2007. Berlin http://www.bundesfinanz-ministerium.de/cln_05/nn_1928/DE/Geld__und__Kredit/Kapitalmarktpolitik/002a,templateId=raw,property=publicationFile.pdf. Accessed 04.08.2008.

Busch, A. (2001). Kee** the state at arm’s length: Banking supervision and deposit insurance in Germany, 1974–1984. In M. Bovens, P. ‘t Hart, & B. G. Peters (Eds.), Success and failure in public governance: A comparative analysis. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Busch, A. (2004). Institutionen, Diskurse und ‘policy change’. Bankenregulierung in Großbritannien und der Bundesrepublik (Institutions, discourses and ‘policy change’. Bank regulation in Great Britain and the Federal Republic). Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 34, 127–150.

Calomiris, C. W., & Kahn, C. M. (1991). The role of demandable debt in structuring optimal banking arrangements. American Economic Review, 81, 497–513.

Caprio, G., & Klingebiel, D. (2003). Episodes of systemic and borderline financial crises. mimeo: World Bank.

Cargill, T. (2001). Central banking, financial, and regulatory change in Japan. In M. Blomström, B. Gagnes, & S. La Croix (Eds.), Japan`s new economy: Continuity and change in the twenty-first century (pp. 145–161). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chan, Y.-S., Greenbaum, S. J., & Thakor, A. V. (1992). Is fairly priced deposit insurance possible? The Journal of Finance, 47, 227–245.

Chari, V. V., & Jagannathan, R. (1988). Banking panics, information, and rational expectations equilibrium. The Journal of Finance, 43, 749–761.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Detragiache, E. (2002). Does deposit insurance increase banking system stability? An empirical investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49, 1373–1406.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Huizinga, H. (1999). Market discipline and financial safety net design. World Bank. Policy Research Paper No. 2183.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Sobaci, T. (2001). Deposit insurance around the world. World Bank Economic Review, 15, 481–490.

Deposit Insurance Company of Japan. (2006). Annual report 2005. April 2005–March 2006, Tokyo.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (1992). Deposit protection schemes in the Federal Republic of Germany. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, July, 28–45.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2000a). Deposit protection and investor compensation in Germany. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, July, 29–45.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2000b). The Deutsche Bundesbank`s involvement in banking supervision. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, September, 31–43.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2003). Stress testing the German banking system. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, December, 53–61.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2004a). Credit risk transfer instrument: Their use by German banks and aspects of financial stability. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, April, 27–45.

Deutsche Bundesbank. (2004b). Credit default swaps—functions, importance and information content. Monthly Report of the Deutsche Bundesbank, December, 43–56.

Deutsche Bundesbank-Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht. (2002). Gemeinsame Presseerklärung der Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht und der Deutschen Bundesbank (Joint press release by the Federal Financial Supervisory Authority and the Deutsche Bundesbank). Frankfurt/Main, Bonn, 4 November 2002.

Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. (2006). Evaluierungsuntersuchungen zur Bewertung der Aufsicht der Kreditwirtschaft und Erstellung eines Erfahrungsberichts (Erfahrungsbericht Bankenaufsicht) (Experience report banking supervision). Berlin. http://www.diw.de/deutsch/produkte/publikationen/diwkompakt/docs/diwkompakt_2006-024.pdf. Accessed 04.08.2008.

Dewatripont, M., & Tirole, J. (1993a). The prudential regulation of banks. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dewatripont, M., & Tirole, J. (1993b). Efficient governance structure: Implication for banking regulation. In C. Mayer & X. Vives (Eds.), Capital markets and financial intermediation (pp. 12–35). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Diamond, D. W. (1984). Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Review of Economic Studies, 51, 393–414.

Diamond, D. W., & Dybvig, P. H. (1983). Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy, 91, 401–419.

Diamond, D. W., & Rajan, R. G. (2000). A theory of bank capital. Journal of Political Economy, 55, 2431–2465.

Diamond, D. W., & Rajan, R. G. (2001). Liquidity risk, liquidity creation and financial fragility: A theory of banking. Journal of Political Economy, 109(2), 287–327.

Diamond, D. W., & Rajan, R. G. (2005). Liquidity shortages and banking crisis. The Journal of Finance, 60, 615–647.

Dietrich, D., & Hauck, A. (2007). Bank lending, bank capital regulation and efficiency of corporate foreign investment. IWH Discussion Paper No. 4/2007, Halle/Saale.

Dietrich, D., & Vollmer, U. (2006). Banks’ internationalization strategies: The role of bank capital regulation. IWH Discussion Paper No. 18/2006, Halle/Saale.

Dionne, G. (2003). The foundations of banks’ risk regulation: A review of the literature. CIRPÉE Working Paper 03-46, Centre interuniversitaire sur le risque, les politiques économiques et l’emploi, Montreal.

Edwards, J., & Fischer, K. (1994). Banks, finance and investment in Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fecht, F. (2004). On the stability of different financial systems. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2(6), 969–1014.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. (2003). Idee einer Auffanggesellschaft für Kredite stößt auf Ablehnung (Idea of a bad bank refused). No. 47, 25.02.2003, 20.

Freixas, X., Giannini, C., Hoggarth, G., & Soussa, F. (2000). Lender of last resort: What have we learned since Bagehot? Journal of Financial Services Research, 18, 63–84.

Freixas, X., & Rochet, J. C. (1997). Microeconomics of banking. Cambridge, London: MIT Press.

Fries, S., Mason, R., & Perraudin, W. (1993). Evaluating deposit insurance for Japanese banks. Journal of the Japanese and International Economy, 7, 356–386.

Fukuda, S., & Koibuchi, S. (2006). Furyou saiken to furyou houki: mein banku no hashirusugiru futan (Bad loans and write-offs: Overrunning burden of the Main bank) (in Japanese). (Keizai kenkyuu) The Economic Review (in Japanese), 57(2), 110–120.

Garcia, G. (1999). Deposit insurance: A survey of actual and best practices. IMF Working Paper No. 99|54.

Gennotte, G., & Pyle, D. (1991). Capital controls and bank risk. Journal of Banking and Finance, 15, 805–824.

Gerring, J. (2004). What is a case study and what is it good for? American Political Science Review, 98(2), 341–354.

Ghauri, P. (2004). Designing and conducting case studies in international business research. In R. Marschan-Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business (pp. 109–124). Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Gilbert, R. A. (1992). The effects of legislating prompt corrective action on the bank insurance fund. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Quarterly Review, 74(4), 3–22.

Guinnane, T. (2002). Delegated monitors, large and small: Germany’s banking system, 1800–1914. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), 73–124.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2003). People’s opium? Religion and economic attitudes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 225–282.

Hall, P. E., & Soskice, D. (2001). An introduction into varieties of capitalism. In P. E. Hall & D. Soskice (Eds.), Varieties of capitalism. The institutional foundations of comparative advantage (pp. 1–68). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hakenes, H. (2004). Banks as delegated risk managers. Journal of Banking & Finance, 28, 2399–2426.

Handelsblatt. (2006). Staat zahlt nicht für die BaFin (State does not pay for BaFin). No. 146, 26.07.2006, 21.

Hart, O. D., & Jaffee, D. M. (1974). On the application of portfolio theory to depository financial intermediaries. Review of Economic Studies, 41, 129–147.

Hatakeda, T. (2007). Waga kuni no ginkou bumon ni okeru ryuudousei juyou nit suite- kyouwa bun kaiki bunseki ni yoru kenshou (Bank’s demand for liquidity in Japan. Co-integration regression analysis). Kokumin-Keizai Zasshi (Journal of Economics & Business Administration, in Japanese), 196(3), 43–55.

Hori, H. (2005). The changing Japanese political system: The Liberal Democratic Party and the Ministry of Finance. London, New York: Routledge.

Hovakimian, A., Kane, E., & Laeven, L. (2002). How country and safety-net characteristics affect bank risk-shifting. mimeo: World Bank/Boston College.

International Monetary Fund. (2003a). Japan: Financial system stability assessment and supplementary information. IMF Country Report No. 03/287, Washington.

International Monetary Fund. (2003b). Germany: Financial system stability assessment, including reports on the observance of standards and codes on the following topics: Banking supervision, securities regulation, insurance regulation, monetary and fiscal policy transparency, payment systems, and securities settlement. IMF Country Report No. 03/343, Washington.

Ito, T., & Melvin, M. (2001). Japan’s big bang and the transformation of financial markets. In M. Blomström, B. Gagnes, & S. La Croix (Eds.), Japan’s new economy: Continuity and change in the twenty-first century (pp. 162–174). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jacklin, C., & Bhattacharya, S. (1988). Distinguishing panics and information-based runs: Welfare and policy implications. Journal of Political Economy, 96, 568–592.

Jakivuolle, E., & Vesala, T. (2007). Portfolio effects and efficiency of lending under Basel II. Bank of Finland Research Discussion Paper No. 13/2007, Helsinki.

Kahane, Y. (1977). Capital adequacy and regulation of financial intermediaries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 1, 207–218.

Kahn, C., & Santos, J. A. C. (2005). Allocating bank regulatory powers: Lender of last resort. European Economic Review, 49, 2107–2136.

Kahn, C., & Santos, J. A. C. (2006). Who should act as a lender of last resort? An incomplete contracts model: A comment. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 38(4), 1111–1118.

Kanatas, G. (1986). Deposit insurance and the discount window: Pricing under asymmetric information. The Journal of Finance, 42(2), 437–450.

Kawai, M. (2005). Reform of the Japanese banking system. International Economics and Economic Policy, 2, 307–335.

Kim, D., & Santomero, A. M. (1988). Risk in banking and capital regulation. The Journal of Finance, 43, 1219–1233.

Koehn, M., & Santomero, A. M. (1980). Regulation of bank capital and portfolio risk. The Journal of Finance, 35, 1235–1244.

Krümmel, H.-J. (1980). German universal banking scrutinized. Journal of Banking and Finance, 4, 33–55.

Kudrna, Z. (2007). Banking reform in China. Driven by international standards and Chines specifics. MPRA Paper No. 7320, Munich mimeo.

La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. The Journal of Finance, 52, 1131–1150.

La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113–1155.

Laeven, L. (2002a). Bank risk and deposit insurance. World Bank Economic Review, 16, 109–137.

Laeven, L. (2002b). Pricing of deposit insurance. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2871, Washington.

Laeven, L. (2002b). International evidence on the cost of deposit insurance. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 42, 721–732.

Lehmbruch, G. (1997). From state of authority ro network state: The German state in developmental perspective. In M. Marumatsu & F. Naschold (Eds.), State and administration in Japan and Germany. A comparative perspective on continuity and change (pp. 39–62). Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Leland, H. E., & Pyle, D. H. (1977). Informational asymmetries, financial structure, and financial intermediation. The Journal of Finance, 32, 371–387.

Luney, P. R., Jr. (1989). Traditions and foreign influences: Systems of law in China and Japan. Law and Contemporary Problems, 52(2), 129–150.

Marschan-Piekkari, R., & Welch, C. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Muramatsu, M., & Naschold, F. (Eds.). (1997). State and administration in Japan and Germany. A comparative perspective on continuity and change. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter.

Merton, R. C. (1977). An analytic derivation of the cost of deposit insurance and loan guarantees. Journal of Banking and Finance, 1, 512–520.

Miyao, R. (2008). Nihon ginkou shinseidou no wadai (Issues of the new Japanese banking system). Economy, Society and Policy, 434, 24–27 (in Japanese).

Morgan, G. (2005). Introduction. In G. Morgan, R. Whitley, & E. Moen (Eds.), Changing capitalisms? Internationalization, institutional change, and systems of exconomic organization (pp. 1–18). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mulgan, A. G. (2002). Japan`s failed revolution: Koizumi and the politics of economic reform. The Australian National University: Asia Pacific Press.

Nagahata, T., & Sekine, T. (2002). The effects of monetary policy on firm investment after the collapse of the asset price bubble: An investigation using Japanese micro data. Bank of Japan Working Paper Series, No. 02-3, Tokyo.

Nakaso, H. (2001). The financial crisis in Japan during the 1990s: How the Bank of Japan responded and the lessons learnt. BIS Papers No 6, Basel, October.

Negishi, M. (2003). Government intervenes to rescue Ashikaga bank. Koizumi treads delicate line over 1 trillion yen failure. The Japan Times Online, Sunday, November 30, 2003, http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20031130a1.html.

Noguchi, Y. (1994). The ‘bubble’ and economic policies in the 1980s. Journal of Japanese Studies, 20(2), 291–329.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ogura, S. (2002). Banking, the state and industrial promotion in develo** Japan. Houndmills, Basingstoke, New York: Palgrave.

Pagano, M. (1993). Financial markets and growth: An overview. European Economic Review, 37, 613–622.

Park, S. (1995). Market discipline by depositors: Evidence from reduced form equations. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 35, 497–514.

Patrick, H. (1994). The relevance of Japanese finance and its main bank system. In M. Aoki & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system. Its relevance for develo** and transforming economies (pp. 353–408). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Paul, S., Stein, S., & Uhde, A. (2007). Measuring the quality of banking supervision in Germany. mimeo: Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Pennacchi, G. (1987). Alternative forms of deposit insurance: Pricing and bank incentive issues. Journal of Banking and Finance, 11, 291–312.

Porter, M. E., Takeuchi, H., & Sakakibara, M. (2000). Can Japan compete? Houndmills. Basingstoke: MacMillan.

Pyle, D. (1971). On the theory of financial intermediation. The Journal of Finance, 26(3), 737–747.

Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (2003). Saving capitalism from the capitalists: Unleashing the power of financial markets to create wealth and spread opportunity. New York: Crown Business.

Repullo, R. (2000). Who should act as a lender of last resort? An incomplete contracts model. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 32, 580–605.

Rochet, J.-C. (1992). Capital requirements and the behaviour of commercial banks. European Economic Review, 43, 981–990.

SVR-Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. (2007). Jahresgutachten: 2007/08: Das Erreichte nicht verspielen (Annual report 2007/2008). Wiesbaden.

Santos, J. A. C. (2001). Bank capital regulation in contemporary banking theory: A review of the literature. Financial Markets, Institutions, Instruments, 10(2), 41–84.

Saunders, A., & Wilson, B. (1996). Contagious bank runs: Evidence from the 1929–1933 period. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 5(4), 409–423.

Schmitter, P. C., & Streeck, W. (1985). Community, market, state and associations? The prospective contribution of interest governance to social order. In P. C. Schmitter & W. Streeck (Eds.), Private interest government: Beyond market and state. London: Sage Publications.

Sleet, C., & Smith, B. D. (2000). Deposit insurance and lender of last resort functions. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 32(3), 518–575.

Stulz, R., & Williamson, R. (2003). Culture, openness, and finance. Journal of Financial Economics, 70, 313–349.

Suzuki, Y. (1980). Money and banking in contemporary Japan. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Suzuki, Y. (1987). The Japanese financial system. Oxford: Claredon Press.

The Japan Times Online. (2001). Coalition unveils market-boosting plan. Saturday, February 10, 2001, http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/nn20010210a3.html.

Tilly, R. H. (1986). German banking, 1850–1914: Development assistance for the strong. Journal of European Economic History, 15, 113–152.

Tilly, R. H. (1991). An overview of the role of the large German banks up to 1914. In Y. Cassis (Ed.), Finance and financiers in European history, 1880–1960 (pp. 94–112). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ueda, K. (1994). Institutional and regulatory frameworks for the main bank system. In M. Aoki & H. Patrick (Eds.), The Japanese main bank system. Its relevance for develo** and transforming economies (pp. 89–108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ueda, K. (2000). Causes of Japan’s banking problems in the 1990s. In T. Hoshi & H. T. Patrick (Eds.), Crisis and change in Japanese Financial System. Boston: Springer.

van Rixtel, A. (2002). Informality and monetary policy in Japan: The political economy of bank performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

VanHoose, D. D. (2006). Bank behavior under capital regulation: What does the academic literature tell us? NFI Working Paper No. 2006-WP-04, Indiana State University, Terre Haute.

Vitols, S. (2001). The origins of bank-based and market-based financial systems: Germany, Japan, and the United States. In K. Yamamura & W. Streeck (Eds.), The origins of nonliberal capitalism. Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press.

Vitols, S. (2003). From banks to markets: The political economy of liberalization of the German and Japanese financial systems. In K. Yamamura & W. Streeck (Eds.), The end of diversity? Prospects for German and Japanese Capitalism (pp. 24–260). Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press.

Watanabe, W. (2008). 1990 nendai ni ginko wo tsujita shikin no nagare ha dou henka shitaka? (How did the financing of Japanese banks changed in the 1990’s?). Financial Review, 88, 39–56 (in Japanese).

Whitley, R. D. (1999). Divergent capitalisms: The social structuring and change of business systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Woo, D. (1999). In search of ‘capital crunch’. Supply factors behind the credit slowdown in Japan. IMF Working paper WP/99/3, Washington.

Yamamoto, H. (2003). New public management—Japan’s practice. Institute for International Policy Studies Policy paper 293E, mimeo.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research. Design and methods (3rd ed.). London, New Dehli: Sage.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank two anonymous referees for helpful comments (without implicating them). Also, we are indebted to Hiroshi Nakaso (Bank of Japan, Tokyo), Yutaka Nishigaki and Nobusuke Tamaki (both Deposit Insurance Corporation of Japan, Tokyo), and Akihiko Watanabe (Bank of Japan, Osaka Branch). Research assistance by Monika Bucher and proofreading by David Beckstead is also acknowledged. Of course, the usual disclaimer applies. Parts of this research were done while Vollmer was on leave at Kobe University. He wants to thank Kobe University for its hospitality and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bebenroth, R., Dietrich, D. & Vollmer, U. Bank regulation and supervision in bank-dominated financial systems: a comparison between Japan and Germany. Eur J Law Econ 27, 177–209 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-008-9084-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10657-008-9084-4

Keywords

- Japan and Germany

- Bank regulation and supervision

- Deposit insurance

- Lender of last resort

- Forbearance

- Varieties of capitalism