Abstract

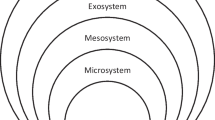

Secondary-tertiary transition issues are explored from the perspective of ways of doing mathematics that are constituted in the implicit aspects of teachers’ action. Theories of culture (Hall, 1959) and ethnomethodology (Garfinkel, 1967) provide us with a basis for describing and explicating the ways of doing mathematics specific to each teaching level, according to the “accounts” provided by the teachers involved in this research project. To borrow from Hall (1959), the “informal” mode of mathematical culture specific to each teaching level plays a key role in attempts to better grasp transition issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Espace Mathématique Francophone (EMF) 2003, 2006, 2009, 2015; PME 2011; PME-NA 2012; CERME 2010

For example, if at the secondary level, letters represent essentially real numbers; at the tertiary level, particularly in the linear algebra course, letters represent various mathematical objects: real numbers, complex numbers, matrices, geometrical vectors, algebraic vectors, polynomial expressions, etc. This makes the formal mathematical language difficult to understand and use for many students (Corriveau & Tanguay, 2007)

Tertiary mathematics teaching has been the subject of several research studies (see the “How we Teach” project reported in Jaworski & Matthews, 2010). Some studies bearing more directly on transition issues have focused more specifically on the perspective of teachers regarding transition (Hong et al., 2009) or that of students regarding their teachers (De Guzman, Hodgson, Robert, & Villani, 1998), but they shed light partially on specific issues linked to transitional issues.

Students had to solve the following system of equations for all values of the constants a and b, with the help of the teacher (in linear algebra)

$$ \begin{array}{l}x+y+z=5\hfill \\ {}x\hbox{--} y+az=3\hfill \\ {}2x+y+z=b\hfill \end{array} $$Cégep is a French acronym for Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (referred to in English as General and Vocational College). In Quebec, the “cégep level” lasts 2 years (grades 12 and 13, students of 17 to 19 years old) in the case of pre-university programs and 3 years in the case of technical/vocational programs. This level is, like the university level, part of the province’s system of higher education. “Cégep” institutions are independent of both secondary institutions (grades 7 to 11) and universities and lead to a degree specific to that level. Teachers receive formal training in a given discipline (e.g., masters in mathematics) and have access to research grants (in mathematics education), but they are not required to do research. So mathematics teachers at the Cégep are not doing mathematics for the purpose of scholarship and publication in mathematics.

Please note that while the general focus of our research concerns the secondary-tertiary transition, for the purposes of clarity, we shall describe those teachers and institutions participating in our study as “postsecondary”—in reference to the specific level of the Quebec higher education system concerned.

These ways of doing mathematics are situated in the context of teaching and therefore include thinking about and planning how to do mathematics with students and how to represent mathematical concept for the purpose of teaching.

Ethnomethodology refers to “ethno-methods” and “-logy”—i.e., the study of the methods used by a particular sociocultural group in its everyday activities for understanding and producing the social order in which its members live.

Ethnomethodology is rooted in this reflexive and interpretative capacity of each social actor, inseparable from action: « Le mode de connaissance pratique c’est cette faculté d’interprétation que tout individu, savant ou ordinaire, possède et met en œuvre dans la routine de ses activités pratiques quotidiennes (…) procédure régie par le sens commun, l’interprétation est posée comme indissociable de l’action et comme également partagée par l’ensemble des acteurs sociaux… » (Coulon 1993, p. 15)

“Territory” is an evocative metaphor serving to convey the idea of a “land” that people organize so as to be able to “live” in it (Raffestin, 1981). This space is continually undergoing organization.

The secondary teachers were Sam, Serge and Scott and the postsecondary (cégep) teachers were Colin, Colette and Corinne.

However, when the topic at hand is limit, f and g are instead the letters used to symbolize the associated functions.

References

Artigue, M. (2004). Le défi de la transition secondaire/supérieur: Que peuvent nous apporter les recherches didactiques et les innovations développées dans ce domaine [The challenge of secondary-postsecondary transition: What can bring research in mathematics education and innovations developed in this field?]. Paper presented at the 1st Canada/France Meeting in the Mathematical Sciences, Toulouse.

Bednarz, N. (2009). Analysis of a Collaborative Research Project: A researcher and a teacher confronted to teaching mathematics to students presenting difficulties. Mediterranean Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 8(1), 1–24.

Bednarz, N. (2013). Recherche collaborative et pratique enseignante: Regarder ensemble autrement [Collaborative research and teachers practice: Looking together differently]. Paris: l’Harmattan.

Bosch, M., & Chevallard, Y. (1999). La sensibilité de l’activité mathématique aux ostensifs: objet d’étude et problématique [The sensitivity of mathematical activity to ostensives: Object of study and problematics]. Recherches en Didactique des Mathématiques, 19(1), 77–123.

Bosch, M., Fonseca, C., & Gascon, J. (2004). Incompletud de las organizaciones matematicas locales en las instituciones escolares [Incompleteness of local mathematical organizations in school institutions]. Recherches en Didactique des Mathematiques, 24(2–3), 205–250.

Chellougui, F. (2004). L’utilisation des quantificateurs universel et existentiel en première année universitaire entre l’explicite et l’implicite [The use of universal and existential quantifiers in first university year: Between the explicit and the implicit]. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 and Université de Tunis.

Cicourel, A. V. (1974). Interpretive procedures and normative rules in the negotiation of status and role. In Cognitive sociology: Language and meaning in social interaction (pp. 11–41). New York: The Free Press.

Corriveau, C. (2007). Arrimage secondaire-collégial: démonstration et formalisme [Articulation between secondary and postsecondary levels: Demonstration and formalism]. (mémoire de maîtrise en didactique des mathématiques non publié). Université du Québec à Montréal.

Corriveau, C. (2009). Démonstration et formalisme en algèbre linéaire [Demonstration and formalism in linear algebra]. In A. Kuzniak & M. Sokhna (Eds.), Actes du colloque Espace Mathématique Francophone. Enseignement des mathématiques et développement: enjeux de société et de formation (pp. 950–959). Dakar: Université Cheikh Anta Diop.

Corriveau, C., & Tanguay, D. (2007). Formalisme accru du secondaire au collégial: les cours d’Algèbre linéaire comme indicateurs [Increased formalism from secondary to postsecondary level: Linear algebra courses as indicators]. Bulletin de l’Association Mathématique du Québec (AMQ), XLVII(1), 6–25.

Coulon, A. (1987). L’ethnométhodologie [Ethnomethodology] Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Coulon, A. (1993). Ethnométhodologie et éducation [Ethnomethodology and education]. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Davidson Wasser, J., & Bresler, L. (1996). Working in the interpretive zone: Conceptualizing collaboration in qualitative research teams. Educational Researcher, 25(5), 5–15.

De Guzman, M., Hodgson, B.R., Robert, A., Villani, V. (1998). Difficulties in the passage from secondary to tertiary education. In Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians (pp. 747-762). Berlin: Documenta mathematica, extra volume ICM.

De Vleeschouwer, M., & Gueudet, G. (2011). Secondary-tertiary transition and evolution of didactic contract: The example of duality in linear algebra. In M. Pytlak, T. Rowland, & E. Swoboda (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 7 (pp. 2113–2122). Rzesvow: University of Rzesvow.

Desgagné, S. (2007). Le défi de coproduction de savoir en recherche collaborative. Autour d’une démarche de reconstruction et d’analyse de récits de pratique enseignante [The challenge of coproduction of knowledge in collaborative research: Around a reconstruction and analysis of teachers practice narratives]. In M. Anadon (Ed.), La recherche participative. Multiples regards (pp. 89–121). Québec City: Presses de l’université du Québec.

Desgagné, S., Bednarz, N., Couture, C., Poirier, L., & Lebuis, P. (2001). L’approche collaborative de recherche en éducation: un rapport nouveau à établir entre recherche et formation [Collaborative approach of research: A new relation to establish between research and professional development]. Revue des Sciences de l’Education, XXVII(1), 33–64.

Drouhard, J.-P. (2006). Prolégomènes “épistémographiques” à l’étude des transitions dans l’enseignement des mathématiques [« Epistemographiques » Prolegomena to the study of transitions in mathematics education]. In N. Bednarz & C. Mary (Eds.), Actes du 3e colloque international Espace Mathématique Francophone (CD-ROM). Sherbrooke: Éditions du CRP.

Durand-Guerrier, V. (2003). Synthèse du Thème 5. Transitions institutionnelles [Synthesis of theme 5. Institutional transitions]. In H. Smida (Ed.), Actes du 2e colloque international Espace Mathématique Francophone (CD-Rom). Tozeur: Commission Tunisienne pour l’Enseignement des Mathématiques et Association Tunisienne des Sciences Mathématiques.

Garfinkel, H. (1963). A conception of and experiments with “trust” as a condition of concerted stable actions. In O. J. Harvey (Ed.), The production of reality: Essays and readings on social interaction (pp. 381–392). New York: Ronald Press.

Garfinkel, H. (2007). Recherche en ethnométhodologie [Studies in ethnomethodology]. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France].

Garfinkel, H., & Sacks, H. (1970). On formal structures of practical actions: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Educational Division.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

Gueudet, G. (2008). Investigating the secondary-tertiary transition. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 67, 237–254.

Gyöngyösi, E., Solovej, J.-P., & Winsløw, C. (2011). Using CAS based work to ease the transition from calculus to real analysis. In M. Pytlak, T. Rowland, & E. Swoboda (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 7 (pp. 2002–2011). Poland: Rzesvow.

Hall, E. T. (1984). Le Langage silencieux. Paris: Seuil. [The silent language]

Hong, Y., et al. (2009). A comparison of teacher and lecturer perspectives on the transition from secondary to tertiary mathematics education. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 40(7), 877–889.

Jaworski, B., & Matthews, J. (2010). How we teach mathematics: Discourses on/in university teaching. In M. Pytlak, T. Rowland, & E. Swoboda (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 7 (pp. 2113–2122). Poland: Rzesvow.

Najar, R. (2011). Notions ensemblistes et besoins d’apprentissage dans la transition secondaire-supérieur [Set concepts and learning needs in the secondary-postsecondary transition]. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics, and Technology Education, 11(2), 107–128.

Praslon, F. (2000). Continuités et ruptures dans la transition Terminale S / DEUG Sciences en analyse: Le cas de la notion de dérivée et son environnement [Continuities and discontinuities in the transition between the last year of secondary school- Terminale S- and the first year of university-DEUG science- in analysis: The case of the derivative concept and its environment]. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Université Paris 7, Paris, France.

Raffestin, C. (1981). Québec comme métaphore [Quebec as a metaphor]. Cahiers de Géographie du Québec, 25(64), 61–70.

Sawadogo, T. (2014). Transition secondaire-supérieur: cause d’échec en mathématiques dans les filières scientifiques de l’Université de Ouagadougou [Secondary-postsecondary transition: Cause of failure in mathematics in the scientific program of the university of Ouagadougou]. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Université de Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

Stadler, E. (2011). The same but different: Novice university students solve a textbook exercise. In M. Pytlak, T. Rowland, & E. Swoboda (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 7. Poland: Rzesvow.

Vandebrouck, F. (2011a). Perspectives et domaines de travail pour l’étude des fonctions [Perspectives and work spaces for the study of functions]. Annales de Didactique et de Sciences Cognitives, 16, 149–185.

Vandebrouck, F. (2011b). Students’ conceptions of functions at the transition between secondary school and university. In Pytlak, M., Rowland, T. and Swoboda, E. (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 7, Rzesvow, Poland.

Weber, K., & Alcock, L. (2004). Semantic and syntactic proof productions. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 56, 209–234.

Winsløw, C. (2007). Les problèmes de transition dans l’enseignement de l’analyse et la complémentarité des approches diverses de la didactique [Transition issues in the teaching of analysis and the complementarity of different approaches in « didactique »]. Annales de Didactique et de Sciences Cognitives, 12, 195–215.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10649-017-9766-3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corriveau, C., Bednarz, N. The secondary-tertiary transition viewed as a change in mathematical cultures: an exploration concerning symbolism and its use. Educ Stud Math 95, 1–19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-016-9738-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-016-9738-z