Abstract

To what extent are epistemic curiosity and situational interest different indicators for the same underlying psychological mechanism? To answer this question, we conducted two studies. In Study 1, we administered measures of epistemic curiosity and situational interest to 158 students from an all-boys secondary school. The data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis to find out whether a one-factor or a two-factor solution provides the best fit to the data. The findings supported a one-factor solution. A two-factor solution was only satisfactorily supported if one accepted that the two latent constructs were correlated .99. Study 2 was an experiment in which we experimentally manipulated the amount of prior knowledge 148 students had about a particular thermodynamic phenomenon. Epistemic curiosity and situational interest were each measured four times: before a text was studied, before and after a problem was presented, and after a second text was read. The treatment group studied a text explaining the problem after the problem was presented, whereas the control group read it before the problem was presented. The control group, in other words, gained prior knowledge about the problem. In the treatment group, both epistemic curiosity and situational interest significantly increased while being confronted with the problem. This was not the case in the control group. In addition, only in the treatment group scores on both measures significantly decreased after the text explaining the problem was studied. These findings support a knowledge gap account of both situational interest and epistemic curiosity, suggesting an identical underlying psychological mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The relationship between curiosity and interest, two motivational constructs of potential relevance to learning, has become subject of controversy. A recent special issue of Educational Psychology Review (December 2019) contains no less than eight contributions discussing the issue. Opinions vary widely. While some authors argue that there is little to distinguish curiosity and interest (Ainley 2019; Alexander 2019), others emphasize important conceptual and possibly neuroscientific differences between the two (Hidi and Renninger 2019; Murayama et al. 2019; Shin and Kim 2019). One author suggests that curiosity may be a special case of interest (Pekrun 2019). These discussions seem somewhat muddled by the fact that both constructs occur in the literature in at least two different guises: a situationally triggered, variable, manifestation, and a more stable, trait-like one. For curiosity, usually a distinction is made between state and trait epistemic curiosity (e.g., Naylor 1981). For interest, a distinction is assumed between situational and individual interest (Hidi and Renninger 2006; Schiefele 2009). A second problem complicating the discussion is that studies investigating similarities or differences between these constructs in an empirical fashion are presently lacking. The studies reported in this article intend to fill this gap for (state) epistemic curiosity and situational interest.

Both epistemic curiosityFootnote 1 and situational interest tend to be seen as a motivational force that drives learning, and their mobilization is considered an important instructional goal (Alexander 2019; Silvia 2017). On the other hand, they emerged at different times and from rather different research perspectives. Epistemic curiosity was introduced in the 1950s originally to make sense of certain exploratory behaviors of animals in the psychological laboratory (Berlyne 1950, 1954). Situational interest, alternatively, initially under the heading of “text-based interest,” emerged 30 years later in the context of discussions about different types of interest relevant to learning from text (Hidi 1990; Hidi and Baird 1986, 1988; Schraw and Lehman 2001). Then, what do they have in common?

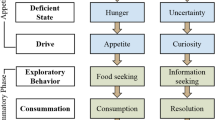

Berlyne (1954) describes epistemic curiosity as a motivational force by which an organism explores its environment seeking for information about it. (Epistēmē is ancient Greek referring to “knowledge,” “science,” or “understanding”) Most researchers in the field agree that this kind of curiosity drives an individual to acquire knowledge about the world. However, differences of opinion persist as to which psychological mechanism underlies epistemic curiosity. Berlyne (1954) initially defined it as a primary—biological—drive, much like hunger or thirst, that is aroused by the situation and can be satisfied by the information gathered. Day (1971) alternatively, favored a cognitive interpretation, assuming that the organism has an intrinsic need to reduce incongruity between his/her existing knowledge of his/her environment and incoming information from that environment. Epistemic curiosity is, in this view, a sense-making process activated whenever a discrepancy emerges between a person’s understanding of the world and how the world appears to him/her in reality, or when certain expectations about that world are violated. Berlyne (1962) and Kagan (1972), finally, describe epistemic curiosity as a process reducing uncertainty. The need to reduce uncertainty regarding reality activates the search for information. More recently, Loewenstein (1994) has proposed a knowledge-gap interpretation of epistemic curiosity. According to Loewenstein, if a person experiences a gap between what (s)he knows and needs to know in order to understand a situation, (s)he experiences a feeling of deprivation. This experience of a deficit drives the learner to search for new knowledge. Epistemic curiosity is thus a cognitively driven motive to close a gap between what is understood and what is not yet understood.

There is some evidence supporting the knowledge-gap account of epistemic curiosity. Loewenstein et al. (1992), for instance, found that epistemic curiosity was largest when participants had partial knowledge of a particular subject, as compared with no knowledge or full knowledge, a finding replicated by Litman et al. (2005). Kang et al. (2009) found that if participants guessed incorrectly in response to trivia questions, curiosity increased. This increased curiosity correlated with increased activity in memory areas in the brain as measured with functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Based on an extensive review of the curiosity literature Grossnickle (2016) defines epistemic curiosity as the desire for knowledge in response to experiencing or seeking out collative variables—stimuli that are novel and complex and are incongruous with expectations. The emergence of epistemic curiosity is accompanied by positive emotions, increased arousal, and exploratory behaviors. Reviewing this literature it becomes clear that Berlyne (1962) uncertainty principle and Loewenstein (1994) knowledge-gap theory as an explanation for the arousal of epistemic curiosity have been influential. Most researchers active in the field tend to refer to their work (e.g., Baranes et al. 2015; Boykin and Harackiewicz 1981; Eren 2009; Halamish et al. 2019; Hardy et al. 2017; Jirout and Klahr 2012; Kang et al. 2009; Korpershoek et al. 2018; Ligneul et al. 2018; Litman 2008; Litman and Spielberger 2003; Lowry and Johnson 1981; Reio Jr et al. 2006).

Whereas epistemic curiosity is described as a predominantly cognitive motivator, situational interest, by contrast, is often construed as an affective response to new information or to a situation not immediately understood (Ainley and Hidi 2014; Ainley et al. 2002; Hulleman et al. 2008; Schiefele 2009). Hidi and Renninger (2006) state that “Situational interest refers to focused attention and the affective reaction that is triggered in the moment by environmental stimuli, which may or may not last over time (p. 113).” Other authors speak of a feeling of enjoyment, accompanied by temporary arousal and increased attention in response to a problem presented to them (Hidi 1990; Schraw and Lehman 2001). We use the word “problem” here as a category name for environmental stimuli (or collative variables) that carry an element of uncertainty or novelty: questions, puzzles, ambiguous statements, brain teasers, counterintuitive events, unfamiliar, or surprising situations. These are “problems” because they require some form of resolution. In addition, it is assumed that the initial triggering of situational interest, and its maintenance, are early stages in the development of a more stable and sustainable individual interest in a particular knowledge domain (Hidi and Renninger 2006). Most situational interest researchers concur with Hidi and Renninger (2006) that situational interest is a transient process characterized by increased arousal, positive affect, and focused attention in response to incongruent information (e.g., Alexander et al. 1995; Chen et al. 2001; Dorfner et al. 2018; Habig et al. 2018; Lin et al. 2013; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. 2010; Magner et al. 2014; Park 2015; Rotgans and Schmidt 2011; Roure et al. 2019b; Schraw 1997; Tapola et al. 2014; Tin 2009a).

Its relationship with the knowledge acquisition process is however more implicit. While most authors assume that situational interest motivates learners to engage with new information in order to learn (Ainley et al. 2002; Rotgans and Schmidt 2011; Schraw and Lehman 2001), others seem to interpret situational interest not so much as a motivational force, but as a positive attitudinal response to particular classroom events. Grossnickle (2016) while discussing the differences between epistemic curiosity and interest, concludes that knowledge is an integral component of the definition of epistemic curiosity, whereas it is not an essential characteristic of interest. Grossnickle states that “… when knowledge does appear in definitions of interest, its role is one of presence, as opposed to definitions of curiosity, which identify curiosity as marked by the absence of knowledge (Grossnickle 2016).”

Despite these differences in emphasis between epistemic curiosity and situational interest, there are also striking similarities. First, most authors from both sides, implicitly or explicitly, acknowledge that their construct is a motivational influence that induces students to learn new information. Second, both sides assume that an environmental stimulus, such as a novel and surprising event, an expectancy violation, and a puzzle, acts as a precipitating event that sets in motion this motivational force. This point of view is, however, not shared by all situational interest researchers (e.g., Ainley et al. 2002; Renninger and Hidi 2015). See also “Discussion.” Third, like epistemic curiosity, situational interest is considered a state rather than a trait, variable over time. And fourth, some situational interest researchers have proposed that like epistemic curiosity, situational interest must decrease when new knowledge is acquired (Alexander 2004; Rotgans and Schmidt 2011, 2014; Schraw and Lehman 2001), suggesting that the new understanding “satisfies” situational interest. In their knowledge deprivation account of situational interest, Rotgans and Schmidt (2011, 2014) have attempted to interpret situational interest in terms of Loewenstein (1994) knowledge-gap theory. They have demonstrated that situational interest is triggered by a precipitating event but decreases when new knowledge is acquired, suggesting that situational interest, like epistemic curiosity, is satiated by new knowledge. Second, when students already have the appropriate knowledge to understand a particular problem, situational interest is not triggered. And third, they have shown that students need to become aware that they have a knowledge deficit if situational interest is to be aroused. Their studies suggest that situational interest, like epistemic curiosity, is closely aligned with the knowledge acquisition process.

The purpose of the studies reported in this article was to find out to what extent epistemic curiosity and situational interest are in fact different names for the same psychological mechanism or that they really do represent different takes on motivation and learning—to study whether they are distant cousins or identical twins. Although several authors use the terms interest and curiosity interchangeably (e.g., Ainley 1987; Boscolo et al. 2011; Connelly 2011; Kashdan 2004), or see interest as one of the causes of curiosity (Litman et al. 2005; Litman and Silvia 2006), to the best of our knowledge no study included measures of both epistemic curiosity and situational interest in an attempt to relate them directly. See also Grossnickle (2016).

In the two studies to be reported below, using a psychometric and an experimental approach, we have tested the hypothesis that epistemic curiosity and situational interest are, in fact, manifestations of the same underlying psychological process. In Study 1, we administered measures of epistemic curiosity and situational interest to students from an all-boys secondary school, soliciting their response to the topic of the “physics of heat.” The data were analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis to find out whether a one-factor solution provides the best fit to the data. This would indicate that the two measures are, in fact, indicators of the same underlying construct. A better fit for a two-factor solution would indicate that they exist as two (possibly correlated) constructs. Study 2 was an experiment in which we manipulated the amount of prior knowledge secondary-school students had about a particular physics-of-heat phenomenon called the Mpemba effect and explored the effect of this manipulation on epistemic curiosity and situational interest respectively.

Study 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Measures of Epistemic Curiosity and Situational Interest

The objective of this study was to conduct a series of confirmatory factor analyses of measures of epistemic curiosity and situational interest to find out if both are indicators of the same underlying latent construct or should be considered two different constructs (possibly correlated to some extent). To that end, we tested four models. The first model assumed that both constructs were entirely independent of each other (i.e., the correlation between the latent factors of situational interest and epistemic curiosity was set to zero). The second model assumed that since both constructs were measured using similar rating-type instruments, a certain amount of common method variance (expressed as a third latent factor partially explaining variation in the other two) would naturally be found between both scales even if the two constructs are referring to different underlying processes. The third model allowed for free estimation of the correlation between both scales (i.e., the correlation between the latent variables of situational interest and epistemic curiosity was freely estimated without restriction). The fourth model consisted of only one latent variable on which both the situational interest and epistemic curiosity items would have to load. If both constructs are measuring the same underlying process, it can be hypothesized that there would be a significant gradual improvement in fit with the data from the first to the fourth model with the one-factor model representing the best fit.

Method

Participants

One-hundred and fifty-eight students from a secondary boys’ school in Parramatta, Australia, participated. Ages ranged from 12 to 13 with mean of 12.67 years (SD = .47).

Materials

Epistemic Curiosity Measure

The epistemic curiosity literature furnishes us with a plethora of questionnaires, each measuring seemingly somewhat different aspects of the construct (e.g., Day 1971; Kashdan et al. 2009; Litman 2008; Litman and Jimerson 2004; Naylor 1981; Vidler and Rawan 1974). See for an overview Grossnickle (2016). In addition, these authors tend to consider epistemic curiosity as a stable—trait-like—characteristic of individual human beings. For instance, Litman and Spielberger's (2003) curiosity questionnaire contains items, such as “Enjoy learning about subjects which are unfamiliar,” “Fascinating to learn new information,” and “Enjoy exploring new ideas,” clearly intended to measure a more stable type of epistemic curiosity. The fluid, variable, and malleable process intended by Berlyne (1954), on the other hand, is often measured by a single item, e.g., “Indicate how curious you are to see the answer to each question” (Boykin and Harackiewicz 1981; Halamish et al. 2019; Kang et al. 2009; Litman et al. 2005).

Therefore, we decided to create a multi-item “state” epistemic curiosity measure based on a content analysis of the epistemic curiosity questionnaires published between 1975 and 2019. See Appendix 1 for the full set of these questionnaires. Table 1 contains the frequencies by which the various epistemic-curiosity-related concepts occur in these questionnaires. Initial rater agreement was 86%. Remaining differences in judgment were resolved by discussion.

The most often occurring concepts—if relevant—were included in the epistemic curiosity measure to be used in the studies described below, ascertaining content validity of the new measure. Table 2 displays the instruction and the items included in the epistemic curiosity measure.

All items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The reliability of the measure was determined by calculating Hancock’s coefficient H. The coefficient H is a construct reliability measure for latent variable systems that represents a relevant alternative to the conventional Cronbach’s alpha. According to Hancock and Mueller (2001), the usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha and related reliability measures is limited to assessing composite scales formed from a construct’s indicators, rather than assessing the reliability of the latent construct itself as reflected by its indicators. The coefficient H is the squared correlation between a latent construct and the optimum linear composite formed by its indicators. Unlike other reliability measures, the coefficient H is never smaller than the best indicator’s reliability. In other words, a factor inferred from multiple indicator variables should never be less reliable than the best single indicator alone. Hancock and Mueller recommended a cut-off value for the coefficient H of .70. The coefficient H for the epistemic curiosity measure was H = .92.

Situational Interest Measure

The literature on situational interest suggests four components covering this construct: enjoyment, interest, focus/concentration, and feeling entertained in response to a triggering event (Ainley and Hidi 2014; Ainley et al. 2002; Hidi 1990; Hidi and Renninger 2006; Schraw and Lehman 2001). See Appendix 2 for the full set of questionnaires used in studies of situational interest between 1988 and 2019. Table 1 contains a content analysis of these questionnaires. To represent these dimensions in a questionnaire, we adapted a measure originally proposed by Rotgans and Schmidt (2011) by focusing on these four characteristics. Table 2 presents the items included in the measure. Students had to respond to these items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The coefficient H for the situational interest measure was H = .84.

Procedure

The measures were administered after a regular class. Students were given a link to an online presentation software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), which they accessed via their tablet computers. All information and instructions were presented via Qualtrics. Students were informed that the school considers teaching them about the “physics of heat.” Students were asked to respond to a set of items regarding this topic. The two questionnaires were presented to the students in a counterbalanced way.

Analysis

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted for each of the four models mentioned above to examine whether the data fitted the hypothesized factor structure and, if so, which model resulted in the best model fit. To examine the goodness-of-fit for the models, we generated the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), and comparative fit index (CFI) along with the χ2 statistic. Cut-off values of .06 (RMSEA), .09 (SRMR), and .95 (CFI) were used in the analysis (Hu and Bentler 1999). The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS AMOS 21 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY).

Results and Discussion

For an overview of the model fit indices pertaining to all four models see Table 3.

The model fit indices of the four models suggest that the one-factor solution in which all situational interest and epistemic curiosity items load on a single factor, resulted in the best model fit: χ2 (35, N = 158) = 32.65, p = .58, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 (95% CI: .00–.00), SRMR = .03. This model resulted in a statistically significantly better model fit than model 1 (Δχ2 (1, N = 158) = 212.50, p < .001) and model 2 (Δχ2 (1, N = 158) = 16.36, p < .001). The difference chi-square test did not reach significance between model 3 and model 4 (Δχ2 (1, N = 158) = .43, p = .52). Note however, that, in model 3, the correlation between the latent situational interest and latent epistemic curiosity factor was .99.

Study 2: Experimental Manipulation of Epistemic Curiosity and Situational Interest

After having established that epistemic curiosity and situational interest seem to refer to the same underlying latent variable structure, we conducted an experiment to examine whether both constructs “behave” in the same manner in response to experimental manipulations: Are they aroused to the same extent in response to a triggering event? And do they both fail to be aroused when participants already do have appropriate prior knowledge? The fact that both constructs are highly correlated—as demonstrated in Study 1—is typically considered convergent validity evidence. However, according to Borsboom et al. (2004), the “correlation between … test scores and other measures cannot provide any more than circumstantial evidence for validity” (p. 1062). What ought to be tested is not just the correlation between two variables purportedly measuring the same construct, but a theory of “response behavior.” That is, if the constructs are identical, they should change in the same direction and magnitude as a result of a chain of events between the subsequent administrations of the measurements. From this it follows that if a precipitating event is presented, both epistemic curiosity and situational interest must increase because in both cases the arousal is caused by an awareness of a knowledge deficit. Consequently, if there is not a knowledge deficit regarding the stimulus at hand, for instance, if students already have the appropriate prior knowledge, no arousal of epistemic curiosity and situational interest is allowed to occur if the underlying psychological mechanism is considered to be the same.

Epistemic curiosity and situational interest were each measured four times, before a text was studied, before and after the Mpemba problem was presented, and after a second text was read. The treatment group read the text explaining the Mpemba problem after the problem was presented, whereas the control group read it before the problem was presented. For the control group, therefore, the problem would no longer be a triggering event; all knowledge relevant to understand it was already acquired. In summary, the following hypotheses were tested: (1) If epistemic curiosity and situational interest are indicators of the same underlying psychological mechanism, then they should show the same pattern of arousal and decrease. (2) If both are responses to a perceived knowledge gap, then, in the treatment condition, both should increase when the Mpemba problem is presented, and decrease after having studied the explanatory text. (3) If both are responses to a perceived knowledge gap, then, in the control condition, receiving prior knowledge about the Mpemba problem, no such increase and decrease is expected.

Method

Participants

One-hundred and forty-eight students from a secondary boys’ school in Parramatta, Australia, participated. Ages ranged between 14 and 17 years, with a mean age of 14.94 years (SD = .48). The sample sizes were computed based on similar studies demonstrating that mean differences tend to revolve around .35 with a mean standard deviation of .60 (Rotgans and Schmidt 2011, 2014, 2017a). The sample size can then be computed with the formula

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43321/), where s is the standard deviation to be expected and d is the difference between means. C is a constant based on α-level and power of the test. With an α < .05 and power = .80, C = 7.85. From this it follows that n should be at least equal to 48. This suggests that our samples are sufficiently large to find treatment effects if they exist.

Materials

Epistemic Curiosity Measure

The same epistemic curiosity measure as in Study 1 was administered. The coefficient H for the four measurements of epistemic curiosity was: measurement 1 H = .94, measurement 2 H = .94, measurement 3 H = .95, and measurement 4 H = .95, all indicating high reliability.

Situational Interest Measure

The same situational interest measure as in Study 1 was administered. The coefficient H for the four measurements of situational interest was: measurement 1 H = .93, measurement 2 H = .92, measurement 3 H = .94, and measurement 4 H = .90.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: a treatment and a control condition. Students were then given a link to an online presentation software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT), which they accessed via their tablet computers. All information and instructions were presented via Qualtrics. In the experiment, both groups were presented the same problem: the “Mpemba effect.” The Mpemba effect is the counterintuitive observation that warmer water freezes faster than cold water, and participants had to think of, and write down a possible explanation for this phenomenon. In the control condition, participants were, however, prior to the confrontation with the Mpemba problem, provided with a 204-word text on the process of evaporation explaining the effect. In the treatment condition, no such information was given. The students in this condition received a “filler” text of equal word count. This filler text was also related to the physics of heat but was irrelevant for understanding the problem. This design was used to ensure that the experiment was fully counterbalanced: all students received the same information albeit in a different sequence. After presentation of the problem, participants in the control condition received the filler text and the treatment condition received the evaporation text. See Appendix 3 for the materials. Epistemic curiosity and situational interest were measured at four points in time. First, as a baseline measurement at the start of the experiment after students were instructed that the topic that they were about to study was about the physics of heat; second, after reading the first text; third, after presentation and self-explanation of the problem; and fourth, after reading the second text, at the end of the experiment. See Fig. 1 for an overview of the experimental set-up.

Analysis

First, a one-way repeated-measures MANOVA was conducted. Time, expressed as the four consecutive measurements (measurement 1, measurement 2, measurement 3, and measurement 4), and epistemic curiosity vs. situational interest were the within-group factors. The between-group factor was treatment vs. control. Non-significant differences would indicate that epistemic curiosity and situational interest changed in the same ways in response to our experimental manipulations. Second, planned pairwise differences were determined by means of Bonferroni analysis of pairwise comparisons using four separate one-way repeated-measures ANOVAs. If our hypothesis was correct, in the treatment condition measurement 3, taken after the problem, should be significantly higher than the three other measurements. This should apply to both epistemic curiosity and situational interest. No such differences would be expected in the control condition. Finally, a manipulation check was carried out to find out whether the experimental manipulation was successful. To that end, the answers the students gave in response to the requirement to think of a possible explanation for the Mpemba problem were used. This was done by counting the number of times the evaporation explanation was mentioned. If the experimental manipulation was to be successful, the students in the control condition would mention this explanation more often because they received the explanatory text before the Mpemba problem and therefore should experience a knowledge gap to a lesser extent. The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY).

Results and Discussion

The one-way repeated-measures MANOVA showed no effect of time on the combined measure: Wilk’s Λ = .98, F(3, 145) = 1.55, p = .16, η2 = .010, nor was the interaction between time and condition significant: Wilk’s Λ = .99, F(3, 145) = .52, p = .79, η2 = .004. These results indicate that there were no differences between the dependent variables, epistemic curiosity, and situational interest, over time and condition. These findings support our hypothesis that both variables show similar patterns of responses over time. See Table 4 for the descriptive statistics.

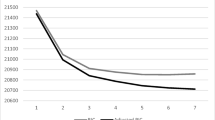

Since, in the present study the pattern of differences between adjacent measurement points, as predicted by the knowledge-gap interpretation of both constructs, is crucial, we conducted four post-hoc comparisons using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, each for one of the conditions and one of the measures. For the treatment condition there was a significant effect of time for both epistemic curiosity and situational interest, respectively: Wilk’s Λ = .84, F(3, 71) = 4.61, p = .005, η2 = .163, and Wilk’s Λ = .88, F(3, 71) = 3.13, p = .031, η2 = .117. Pairwise comparisons indicated that measurement 3, taken after the problem was presented, was significantly higher than all other measurements. This applied to both epistemic curiosity (3 versus 1: p = .008, 3 versus 2: p = .022, and 3 versus 4: p = .009) and situational interest (3 versus 1: p = .02, 3 versus 2: p = .023, and 3 versus 4: p = .045). In the control condition, none of these differences emerged. These data suggest that only among students in the treatment condition, having no prior knowledge of the explanation of the Mpemba problem, epistemic curiosity and situational interest increased, and decreased after the explanatory text was studied, as predicted by the knowledge-deprivation hypothesis. Figure 2 depicts the changes over time for epistemic curiosity and situational interest separately. It shows almost identical patterns for both variables.

In summary, epistemic curiosity and situational interest were equally sensitive to our manipulation of prior knowledge, strengthening our hypothesis that both measures refer to the same psychological mechanism.

The manipulation check showed the experimental manipulation to be successful. After being presented with the Mpemba problem, the students in the control condition mentioned the evaporation explanation significantly more often: Mcontrol = .34 (SD = .56) vs Mtreatment = .15 (SD = .40), F(1,146) = 5.70, p = .018.

General Discussion

The status of curiosity and interest as similar or dissimilar has been, and still is, subject of considerable debate. Dewey’s early work is often referred to as the original source of these concepts as applied to education. Surprisingly, in “How we think” published in 1910, curiosity takes centre stage and interest is only mentioned once (Dewey 1910), whereas in his 1913 book, “Interest and Effort in Education,” the concept of curiosity is entirely absent (Dewey 1913). Litman and Silvia (2006) define interest as a subcategory of curiosity, a point of view shared with Kashdan and Silvia (2009) and Silvia (2006). Alternatively, others see curiosity rather as a subcategory of interest (Boscolo et al. 2011). Again, others use the terms interchangeably (Ainley 1987; Connelly 2011; Silvia 2017) or see them as different but reciprocally related (Arnone et al. 2011). In a recent review, Ainley (2019) suggests that in-the-moment experiences of curiosity and interest both emerge out of exploratory behavior observed in infancy and early childhood.

The studies presented in this article sought to test the hypothesis that epistemic curiosity and situational interest are, in fact, different guises hiding the same psychological mechanism: the need for knowledge emerging in response to the confrontation with a problem. In Study 1, we administered indicators of epistemic curiosity and situational interest to secondary-school students measuring their response to a particular topic to be studied, the physics of heat. Using confirmatory factor analysis, we were able to demonstrate that a one-factor solution including the items of both measures provided the best fit of the data. A two-factor solution only fitted equally well if an almost perfect correlation between the two latent factors was allowed. Study 2 was an experiment in which we measured both epistemic curiosity and situational interest four times over the course of a knowledge acquisition exercise among secondary-school students. In both conditions, the same physics-of-heat problem was presented for which students were asked to find an explanation. The treatment group received a text explaining the problem after they encountered it; the control group received the text before the problem. Only for the treatment group receiving the problem first, epistemic curiosity and situational interest were aroused and decreased after the explanatory text was studied. Since the control group received the explanatory text before the problem, its members did not experience a knowledge gap and therefore did not show arousal and decrease of both variables. These results largely replicate and extend previous studies in which we used problems to arouse situational interest and in which the processing of explanatory texts was shown to decrease situational interest (Rotgans and Schmidt 2011, 2014, 2017b). Over the course of the experiment, epistemic curiosity and situational interest increased and decreased in almost the same way. These findings and those of Study 1 suggest that epistemic curiosity and situational interest, if not different terms for the same psychological mechanism, then at least should be considered identical twins. Both are triggered by an engaging problem, as predicted for epistemic curiosity by Berlyne (1954), and for situational interest by Hidi and Renninger (2006) and others. Both also seem to be satisfied by the opportunity to process knowledge relevant to explaining the phenomena described in the problem as suggested by Loewenstein (1994) for epistemic curiosity and demonstrated by Rotgans and Schmidt (2014) for situational interest. Rotgans and Schmidt (2014) have summarized their knowledge deprivation account of situational interest as follows: “(a) Confronted with a problem not immediately understood, a person engages in an attempt to retrieve knowledge from long-term memory that may help him or her to interpret the problem; (b) If the retrieval fails, the person experiences a gap between what he or she seems to know and what he or she needs to know to understand the problem-at-hand; (c) This awareness of a knowledge deficit leads to increased situational interest for information that may help eliminating the deficit; situational interest is therefore a motivational indicator of the preparedness of the person to engage in processing such information; and (d), the acquisition of new and relevant knowledge satisfies the drive to learn. Hence, situational interest decreases and may even disappear. In (this) proposal, the failed attempt to retrieve relevant knowledge, necessary for understanding the problem, is crucial to the emergence of situational interest (p. 45).”

In our view, and based on the studies presented here, the same psychological mechanism explains how epistemic curiosity works; both concepts refer to the same underlying process.

An obvious objection against our findings may be that situational interest and epistemic curiosity, as operationalized in our studies, do not faithfully represent both constructs as envisioned in the literature. Renninger and Hidi (2016), for instance, suggest that our previous studies of situational interest in fact were studies of epistemic curiosity. We beg to disagree. We believe that our operationalization of situational interest closely matches the definition as proposed by Hidi and Renninger (2006). In addition, as Table 1 indicates, our operationalization matches the most often used concepts in this context. There is hence no reason to believe that our studies were not about situational interest. However, we had to newly construct a (state) epistemic curiosity scale because no such scale exists. It is possible that this operationalization, based on a content analysis of published epistemic curiosity questionnaires, was less successful than hoped for. A colleague reviewing an earlier version of our manuscript suggested that both scales show semantic overlap and that it is therefore no surprise that they correlate highly. If true, this would impede our findings. However, while selecting the items, we took great pains to ensure that the scales did not show more overlap than is suggested by the literature. Inspection of the items demonstrates that the concept of curiosity only appears in the epistemic curiosity scale and interest only in the situational interest scale. Fascination, exploration, and desire appear only in the epistemic curiosity scale, whereas focus, not being distracted, and boredom appear only in the situational interest scale. In line with its definition, knowing more appears prominently (3 times) in the epistemic curiosity scale, while in the situational interest scale there is no explicit reference to a need to know more. The only overlap in terms of the concepts used is fun-enjoyment, obviously because they appear in most definitions. Finally, to check the validity of our findings, we decided to select from each of the measures one item that seems to represent the core of the two constructs: “I think this topic is interesting” and “I am really curious to know more about this topic,” and to redo the analysis of Study 2 based only on these two items. The results were largely similar to those reported above, possibly strengthening the credibility of our findings.

How can our findings be reconciled with the literature that stresses differences between the constructs? Renninger and Hidi (2016), for instance, hypothesize that in the case of curiosity, knowledge acquisition results in a resolution and reduced motivation; in the case of interest increased knowledge is likely to lead to further seeking and increased motivation. In addition, curiosity is a relatively short-term psychological state as it lasts until the information gap is closed or a conflict is resolved. The psychological state of interest, on the other hand, has no such limitations and often continues as interest develops. According to Markey and Loewenstein (2014) curiosity only results from a desire to close an information gap with regard to a specific issue, whereas interest involves engagement in order to learn more about a subject generally. We believe that when these authors speak about interest, they are referring to individual interest, indeed a more stable and enduring process that engages a student with a subject over longer stretches of time and, while doing so, may lead to further learning. However, situational interest has been shown repeatedly to be a short-lived phenomenon in response to a specific environmental stimulus and satiated by knowledge (Alexander 2004). See Rotgans and Schmidt (2017a, 2018) for additional discussion of the relationship and differences between situational and individual interest.

A tempting thought and reasonable hypothesis flowing from our findings is that interest and curiosity, defined as individual interest and “trait” epistemic curiosity, may also be different words for the same psychological process. Our guess however is that this may not be the case. Individual interest as we understand it is an enduring commitment and repeated engagement with a particular subject over time, whereas trait epistemic curiosity shows itself in an ever-changing inquisitiveness after the events in the world as they unfold, much like openness to experience, one of the Big Five personality traits (Litman et al. 2005).

Why is it important to study possible similarities among constructs emerging from different research traditions such as those that were the subject of this article? The first answer is unity of knowledge. If measures deriving from previously separate domains point at the same underlying mechanism (in our case the knowledge-deprivation account), it strengthens both of them. The biologist E.O. Wilson (1999) calls the attempt to unite knowledge from different domains “consilience” and sees it as a necessary step for science to progress. See also Alexander (2019) for an attempt at consilience in the interest/curiosity controversy. The second answer is that researchers from both domains may learn from each other’s methods. For instance, epistemic curiosity researchers sometimes use behavioral or neuroscientific measures (Jirout and Klahr 2012; Kang et al. 2009; Lowry and Johnson 1981; van Schijndel et al. 2018) approaches virtually unknown in the situational interest domain (Hidi and Renninger 2019). A third answer is that such attempt may help reduce the plethora of questionnaires in use in the field. As Appendices 1 and 2 suggest, there is a need to develop further “consilience” among measuring instruments as well.

Where to go from here? Clearly, our findings are preliminary and need further confirmation. One possibility is this: The knowledge-deprivation theory, outlined above, predicts that only if students become aware of a knowledge gap, situational interest is aroused. If epistemic curiosity and situational interest are similar, the same must apply to epistemic curiosity: increase only if the person is aware that he or she has a gap in his or her knowledge. Since students have the possibility to process the same information at different levels of depth (Craik and Lockhart 1972), including the possibility to process information superficially, awareness of a knowledge deficit will not always emerge, and therefore, epistemic curiosity will not always increase.

A second prediction is that participants need at least some prior knowledge in order to make sense of a problem. If the problem is not understood at all, students cannot see that they are missing something. Loewenstein et al. (1992) reports that epistemic curiosity was largest when participants had partial knowledge of a particular subject, as compared with no knowledge or full knowledge. See also Litman et al. (2005). In an unpublished experiment, we presented Singapore primary school pupils with a history problem delineating how it was possible that Hitler, despite never reaching a parliamentary majority, nevertheless became Germany’s “Kanzler” in 1933. Most of the students had never heard of Hitler, nor did they know that a Kanzler is German for prime minister. Hence, situational interest was not aroused. If epistemic curiosity is identical to situational interest, then epistemic curiosity will also not be aroused under such circumstances. These predictions should be subject of further studies aimed at clarifying the relationship between epistemic curiosity and situational interest.

A final issue of concern is the possibility that situational interest may not only be aroused in response to the experience of a knowledge gap. It is possible that contexts other than the confrontation with a triggering event such as a problem also trigger situational interest (Ainley et al. 2002; Renninger and Hidi 2015). If research would show that there are situations in which situational interest is aroused without the accompanying deprivation response, such research would certainly broaden the concept of situational interest beyond the boundaries sketched here and in previous studies.

References

Ainley, M. (1987). The factor structure of curiosity measures: breadth and depth of interest curiosity styles. Australian Journal of Psychology, 39(1), 53–59.

Ainley, M. (2019). Curiosity and interest: emergence and divergence. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 789–806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09495-z.

Ainley, M., & Hidi, S. (Eds.). (2014). Interest and enjoyment. Routledge.

Ainley, M., Hidi, S., & Berndorff, D. (2002). Interest, learning, and the psychological processes that mediate their relationship. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(3), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.94.3.545.

Alexander, P. A. (2004). A model of domain learning: reinterpreting expertise as a multidimensional, multistage process. In D. Y. Dai & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Motivation, emotion, and cognition: integrative perspectives on intellectual functioning and development (pp. 273–298). Routledge.

Alexander, P. A. (2019). Seeking common ground: surveying the theoretical and empirical landscapes for curiosity and interest. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 897–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09508-x.

Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Jetton, T. L. (1994a). The role of subject-matter knowledge and interest in the processing of linear and nonlinear texts. Review of Educational Research, 64(2), 201–252. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543064002201.

Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Schulze, S. K. (1994b). The influence of topic knowledge, domain knowledge, and interest on the comprehension of scientific exposition. Learning and Individual Differences, 6(4), 379–397.

Alexander, P. A., Kulikowich, J. M., & Jetton, T. L. (1995). Interrelationship of knowledge, interest, and recall: assessing a model of domain learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(4), 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.4.559.

Arnone, M. P., Small, R. V., Chauncey, S. A., & McKenna, H. P. (2011). Curiosity, interest and engagement in technology-pervasive learning environments: a new research agenda. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59(2), 181–198.

Baranes, A., Oudeyer, P. Y., & Gottlieb, J. (2015). Eye movements reveal epistemic curiosity in human observers. Vision Research, 117, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2015.10.009.

Berlyne, D. E. (1950). Novelty and curiosity as determinants of exploratory behaviour. British Journal of Psychology. General Section, 41(1–2), 68–80.

Berlyne, D. E. (1954). A theory of human curiosity. British Journal of Psychology, 45(3), 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1954.tb01243.x.

Berlyne, D. E. (1962). Uncertainty and epistemic curiosity. British Journal of Psychology, 53(1), 27–34.

Bhandari, S., Hallowell, M. R., & Correll, J. (2019). Making construction safety training interesting: a field-based quasi-experiment to test the relationship between emotional arousal and situational interest among adult learners. Safety Science, 117, 58–70.

Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2004). The concept of validity. Psychological Review, 111(4), 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.111.4.1061.

Boscolo, P., Ariasi, N., Del Favero, L., & Ballarin, C. (2011). Interest in expository text: How does it flow from reading to writing? Learning and Instruction, 21(3), 467–480.

Boykin, A. W., & Harackiewicz, J. (1981). Epistemic curiosity and incidental recognition in relation to degree of uncertainty—some general trends and intersubject differences. British Journal of Psychology, 72(FEB), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1981.tb02162.x.

Chen, A., & Darst, P. W. (2002). Individual and situational interest: the role of gender and skill. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 27(2), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.2001.1093.

Chen, A., Darst, P. W., & Pangrazi, R. P. (2001). An examination of situational interest and its sources [Article]. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 383–400. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709901158578, 3.

Chen, Y.-C., Pan, Y.-T., Hong, Z.-R., Weng, X.-F., & Lin, H.-S. (2019). Exploring the pedagogical features of integrating essential competencies of scientific inquiry in classroom teaching. Research in Science & Technological Education, Published online first, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02635143.2019.1601075.

Connelly, D. A. (2011). Applying Silvia’s model of interest to academic text: is there a third appraisal? Learning and Individual Differences, 21(5), 624–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2011.04.007.

Craik, F. I. M., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684.

Day, H. I. (1971). The measurement of specific curiosity. In H. I. Day, D. E. Berlyne, & D. E. Hunt (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation: a new direction in education. Hold, Rinehart, & Winston.

Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. DC Heath.

Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. Houghton Mifflin.

Dorfner, T., Förtsch, C., & Neuhaus, B. J. (2018). Effects of three basic dimensions of instructional quality on students’ situational interest in sixth-grade biology instruction. Learning and Instruction, 56, 42–53.

Dousay, T. A. (2016). Effects of redundancy and modality on the situational interest of adult learners in multimedia learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 64(6), 1251–1271.

Durik, A. M., Shechter, O. G., Noh, M., Rozek, C. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2015). What if I can’t? Success expectancies moderate the effects of utility value information on situational interest and performance. Motivation and Emotion, 39(1), 104–118.

Eren, A. (2009). Examining the relationship between epistemic curiosity and achievement goals. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 9(36), 129–144.

Eren, A., & Coskun, H. (2016). Students’ level of boredom, boredom co** strategies, epistemic curiosity, and graded performance. Journal of Educational Research, 109(6), 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.999364.

Grossnickle, E. M. (2016). Disentangling curiosity: dimensionality, definitions, and distinctions from interest in educational contexts. Educational Psychology Review, 28(1), 23–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-014-9294-y.

Grund, A., Schäfer, N., Sohlau, S., Uhlich, J., & Schmid, S. (2019). Mindfulness and situational interest. Educational Psychology, 39(3), 353–369.

Habig, S., Blankenburg, J., van Vorst, H., Fechner, S., Parchmann, I., & Sumfleth, E. (2018). Context characteristics and their effects on students’ situational interest in chemistry. International Journal of Science Education, 40(10), 1154–1175.

Halamish, V., Madmon, I., & Moed, A. (2019). Motivation to learn the long-term mnemonic benefit of curiosity in intentional learning. Experimental Psychology, 66(5), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000455.

Hancock, G. R., & Mueller, R. O. (2001). Rethinking construct reliability within latent systems. In R. Cudeck, S. Du Toit, & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: present and future—a festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog (pp. 195–121). Scientific Software International..

Hardy, J. H., Ness, A. M., & Mecca, J. (2017). Outside the box: epistemic curiosity as a predictor of creative problem solving and creative performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.004.

Hassan, M. M., Bashir, S., & Mussel, P. (2015). Personality, learning, and the mediating role of epistemic curiosity: a case of continuing education in medical physicians. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.07.018.

Hidi, S. (1990). Interest and its contribution as a mental resource for learning. Review of Educational Research, 60(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170506.

Hidi, S., & Baird, W. (1986). Interestingness—a neglected variable in discourse processing. Cognitive Science, 10(2), 179–194.

Hidi, S., & Baird, W. (1988). Strategies for increasing text-based interest and students’ recall of expository texts. Reading research quarterly, 465-483.

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006, Spr). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4.

Hidi, S. E., & Renninger, K. A. (2019). Interest development and its relation to curiosity: needed neuroscientific research. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 833–852. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09491-3.

Hidi, S., Berndorff, D., & Ainley, M. (2002). Children’s argument writing, interest and self-efficacy: an intervention study. Learning and Instruction, 12(4), 429–446.

Hong, J.-C., Chang, C.-H., Tsai, C.-R., & Tai, K.-H. (2019). How situational interest affects individual interest in a STEAM competition. International Journal of Science Education, 41(12), 1667–1681.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hulleman, C. S., Durik, A. M., Schweigert, S. B., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2008). Task values, achievement goals, and interest: an integrative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 398–416.

Jirout, J., & Klahr, D. (2012). Children’s scientific curiosity: in search of an operational definition of an elusive concept. Developmental Review, 32(2), 125–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2012.04.002.

Kagan, J. (1972). Motives and development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 22(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032356.

Kang, M. J., Hsu, M., Krajbich, I. M., Loewenstein, G., McClure, S. M., Wang, J. T. Y., & Camerer, C. F. (2009). The wick in the candle of learning: epistemic curiosity activates reward circuitry and enhances memory. Psychological Science, 20(8), 963–973. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02402.x.

Kashdan, T. B. (2004). Curiosity. In C. Peterson & M. E. P. Seligman (Eds.), Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification (pp. 125–141). Oxford University Press.

Kashdan, T. B., & Silvia, P. J. (2009). Curiosity and interest: the benefits of thriving on novelty and challenge. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 367–374). Oxford University Press.

Kashdan, T. B., Gallagher, M. W., Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Breen, W. E., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. F. (2009). The curiosity and exploration inventory-II: development, factor structure, and psychometrics. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 987–998.

Knogler, M., Harackiewicz, J. M., Gegenfurtner, A., & Lewalter, D. (2015). How situational is situational interest? Investigating the longitudinal structure of situational interest. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 43, 39–50.

Koo, D. M., & Choi, Y. Y. (2010). Knowledge search and people with high epistemic curiosity. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2009.08.013.

Korpershoek, H., Hesseling, A., Venema, F., Verduyn, N., & Talens, R. (2018). Map** out curiosity: a validation study of the epistemic curiosity scale in the Dutch educational context. Pedagogische Studiën, 95(1), 19–33.

Lamnina, M., & Chase, C. C. (2019). Develo** a thirst for knowledge: How uncertainty in the classroom influences curiosity, affect, learning, and transfer. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59, 101785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101785.

Lauriola, M., Litman, J. A., Mussel, P., De Santis, R., Crowson, H. M., & Hoffman, R. R. (2015). Epistemic curiosity and self-regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.017.

Lentillon-Kaestner, V., & Roure, C. (2019). Coeducational and single-sex physical education: students’ situational interest in learning tasks centred on technical skills. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(3), 287–300.

Ligneul, R., Mermillod, M., & Morisseau, T. (2018). From relief to surprise: dual control of epistemic curiosity in the human brain. Neuroimage, 181, 490–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.038.

Lin, H.-S., Hong, Z., & Chen, Y.-C. (2013). Exploring the development of college students’ situational interest in learning science. International Journal of Science Education, 35(13), 2152–2173.

Lin, H. C.-S., Yu, S.-J., Sun, J. C.-Y., & Jong, M. S. Y. (2019). Engaging university students in a library guide through wearable spherical video-based virtual reality: effects on situational interest and cognitive load. Interactive Learning Environments, Online first 1-16.

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Durik, A. M., Conley, A. M., Barron, K. E., Tauer, J. M., Karabenick, S. A., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2010). Measuring situational interest in academic domains. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 647–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409355699.

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Patall, E. A., & Messersmith, E. E. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of situational interest. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(4), 591–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02080.x.

Litman, J. A. (2008). Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1585–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.014.

Litman, J. A., & Jimerson, T. L. (2004). The measurement of curiosity as a feeling of deprivation. Journal of Personality Assessment, 82(2), 147–157.

Litman, J. A., & Mussel, P. (2013). Validity of the interest- and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity model in Germany. Journal of Individual Differences, 34(2), 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000100.

Litman, J. A., & Silvia, P. J. (2006). The latent structure of trait curiosity: evidence for interest and deprivation curiosity dimensions. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86(3), 318–328.

Litman, J. A., & Spielberger, C. D. (2003). Measuring epistemic curiosity and its diversive and specific components. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa8001_16.

Litman, J. A., Hutchins, T. L., & Russon, R. K. (2005). Epistemic curiosity, feeling-of-knowing, and exploratory behaviour. Cognition & Emotion, 19(4), 559–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930441000427.

Litman, J. A., Crowson, H. M., & Kolinski, K. (2010). Validity of the interest- and deprivation-type epistemic curiosity distinction in non-students. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(5), 531–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.05.021.

Loewenstein, G. (1994). The psychology of curiosity—a review and reinterpretation. Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.75.

Loewenstein, G., Adler, D., Behrens, D., & Gillis, J. (1992). Why Pandora opened the box: curiosity as a desire for missing information. Carnegie Mellon University.

Lowry, N., & Johnson, D. W. (1981). Effects of controversy on epistemic curiosity, achievement, and attitudes. Journal of Social Psychology, 115(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1981.9711985.

Magner, U. I., Schwonke, R., Aleven, V., Popescu, O., & Renkl, A. (2014). Triggering situational interest by decorative illustrations both fosters and hinders learning in computer-based learning environments. Learning and Instruction, 29, 141–152.

Markey, A., & Loewenstein, G. (2014). Curiosity. In P. A. Alexander, R. Pekrun, & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education. Routledge.

Mitchell, M. (1993). Situational interest: its multifaceted structure in the secondary mathematics classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(3), 424–436.

Murayama, K., FitzGibbon, L., & Sakaki, M. (2019). Process account of curiosity and interest: a reward-learning perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 875–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09499-9.

Naylor, F. D. (1981). A state-trait curiosity inventory. Australian Psychologist, 16(2), 172–183.

O’Keefe, P. A., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2014). The role of interest in optimizing performance and self-regulation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.02.004.

Palmer, D. H. (2009). Student interest generated during an inquiry skills lesson. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 46(2), 147–165.

Park, S. (2015). The effects of social cue principles on cognitive load, situational interest, motivation, and achievement in pedagogical agent multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 18(4).

Pekrun, R. (2019). The murky distinction between curiosity and interest: state of the art and future prospects. Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 905–914. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09512-1.

Piotrowski, J. T., Litman, J. A., & Valkenburg, P. (2014, Sep-Oct). Measuring epistemic curiosity in young children. Infant and Child Development, 23(5), 542–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1847.

Reio Jr., T. G., Petrosko, J. M., Wiswell, A. K., & Thongsukmag, J. (2006). The measurement and conceptualization of curiosity. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 167(2), 117–135.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2015). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. Taylor & Francis Group: Routledge.

Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2016). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. Routledge.

Ribeiro, L. M., Mamede, S., Moura, A. S., de Brito, E. M., de Faria, R. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2018). Effect of reflection on medical students’ situational interest: an experimental study. Medical Education, 52(5), 488–496.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2011). Situational interest and academic achievement in the active-learning classroom. Learning and Instruction, 21(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.11.001.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2014). Situational interest and learning: thirst for knowledge. Learning and Instruction, 32, 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.01.002.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2017a). Interest development: arousing situational interest affects the growth trajectory of individual interest. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.02.003.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2017b). The role of interest in learning: knowledge acquisition at the intersection of situational and individual interest. In P. O’Keefe & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), The science of interest (pp. 69–93). Springer.

Rotgans, J. I., & Schmidt, H. G. (2018). How individual interest influences situational interest and how both are related to knowledge acquisition: a micro-analytical investigation. Journal of Educational Research, 111(5), 530–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2017.1310710.

Roure, C., Pasco, D., & Kermarrec, G. (2016). Validation de l’échelle française mesurant l’intérêt en situation, en éducation physique. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 48(2), 112–120.

Roure, C., Kermarrec, G., & Pasco, D. (2019a). Effects of situational interest dimensions on students’ learning strategies in physical education. European Physical Education Review, 25(2), 327–340.

Roure, C., Lentillon-Kaestner, V., Méard, J., & Pasco, D. (2019b). Universality and uniqueness of students’ situational interest in physical education: acomparative study. Psychologica Belgica, 59(1), 1–15.

Ruiz-Alfonso, Z., & Leon, J. (2019). Teaching quality: relationships between passion, deep strategy to learn, and epistemic curiosity. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(2), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1562944.

Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 197–222). Routledge.

Schraw, G. (1997). Situational interest in literary text. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(4), 436–456.

Schraw, G., & Lehman, S. (2001). Situational interest: a review of the literature and directions for future research. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009004801455.

Schroeder, M. P. (2013). The relationship between prior knowledge and situational interest when reading text. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(4), 1417–1433.

Shin, D. D., & Kim, S.-i. (2019). Homo curious: curious or interested? Educational Psychology Review, 31(4), 853–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09497-x.

Silvia, P. J. (2006). Exploring the psychology of interest. Oxford University Press.

Silvia, P. J. (2017). Curiosity. In P. A. O’Keefe & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), The science of interest (pp. 97–107). Springer Publishing.

Sun, J. C. Y., & Rueda, R. (2012). Situational interest, computer self-efficacy and self-regulation: their impact on student engagement in distance education. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(2), 191–204.

Tapola, A., Veermans, M., & Niemivirta, M. (2013). Predictors and outcomes of situational interest during a science learning task. Instructional Science, 41(6), 1047–1064.

Tapola, A., Jaakkola, T., & Niemivirta, M. (2014). The influence of achievement goal orientations and task concreteness on situational interest. The Journal of Experimental Education, 82(4), 455–479.

Tin, T. B. (2008). Exploring the nature of the relation between interest and comprehension. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(5), 525–536.

Tin, T. B. (2009a). Emergence and maintenance of student teachers ‘interest’ within the context of two-hour lectures: an actual genetic perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(1), 109–133.

Tin, T. B. (2009b). Features of the most interesting and the least interesting postgraduate second language acquisition lectures offered by three lecturers. Language and Education, 23(2), 117–135.

van Schijndel, T. J. P., Jansen, B. R. J., & Raijmakers, M. E. J. (2018). Do individual differences in children’s curiosity relate to their inquiry-based learning? International Journal of Science Education, 40(9), 996–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1460772.

Vidler, D. C., & Rawan, H. R. (1974). Construct validation of a scale of academic curiosity. Psychological Reports, 35(1), 263–266.

Wilson, E. O. (1999). In A. Alfred (Ed.), Consilience: the unity of knowledge. Knopf.

Wu, P. H., Kuo, C. Y., Wu, H. K., Jen, T. H., & Hsu, Y. S. (2018). Learning benefits of secondary school students’ inquiry-related curiosity: a cross-grade comparison of the relationships among learning experiences, curiosity, engagement, and inquiry abilities. Science Education, 102(5), 917–950. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21456.

Yu, S. J., Sun, J. C. Y., & Chen, O. T. C. (2019). Effect of AR-based online wearable guides on university students’ situational interest and learning performance. Universal Access in the Information Society, 18(2), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-017-0591-3.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Adam Hendry, vice-principal Parramatta High School, Australia, for support in the administration of the questionnaires.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Measures of Epistemic Curiosity 1975–2019

This appendix displays the various measures of epistemic curiosity in use in curiosity research. Potentially appropriate articles were found in a Web of Science search of articles published between 1975 and 2019. Criteria for inclusion were (1) whether the “epistemic curiosity” was found in either title or abstract and (2) whether a measure of epistemic curiosity was reported in full detail. Initially, 144 articles were retrieved. Of these, 31 reported in sufficient detail one or more measures of epistemic curiosity.

Authors | Items |

Eren (2009), Hassan et al. (2015), Litman (2008), Litman et al. (2005), Litman and Mussel (2013), Litman and Spielberger (2003), and Ruiz-Alfonso and Leon (2019) | (10 items) “Enjoy learning about subjects which are unfamiliar” “Fascinating to learn new information” “Enjoy exploring new ideas” “Learn something new/like to find out more” “Enjoy discussing abstract concepts” “See a complicated piece of machinery/ask someone how it works” “New kind of arithmetic problem/enjoy imagining solutions” “Incomplete puzzle/try and imagine the final solution” “Interested in discovering how things work” “Riddle/interested in trying to solve it” 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = almost always) |

Eren and Coskun (2016), Hardy et al. (2017), Koo and Choi (2010), Korpershoek et al. (2018), Lauriola et al. (2015), Litman (2008), Litman et al. (2010), Litman and Mussel (2013), and Piotrowski et al. (2014) | (10 items) I-Type scale “Enjoy exploring new ideas” “Find it fascinating to learn new information” “Enjoy learning about subjects that are unfamiliar to me” “Enjoy discussing abstract concepts” “Learn something new, like to find out more about it” D-type scale “Hours on a problem because I cannot rest without answer” “Brood for a long time to solve problem” “Conceptual problems keep me awake thinking” “Frustrated if I cannot figure out problem, so I work harder“ “Work like a fiend at problems that I feel must be solved” 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = almost always) |

Lamnina and Chase (2019), Naylor (1981), and Reio Jr. et al. (2006) | (Melbourne State Curiosity Inventory 20 items) (Naylor 1981) “I want to know more” “I feel curious about what is happening” “I am feeling puzzled” “I want things to make sense” “I am intrigued by what is happening” “I want to probe deeply into things” “I am speculating about what is happening” “My curiosity is aroused” “I feel interested in things” “I feel inquisitive” “I feel like asking questions about what is happening” “Things feel incomplete” “I feel like seeking things out” “I feel like searching for answers” “I feel absorbed in what I am doing” “I want to explore possibilities” “My interest has been captured” “I feel involved in what I am doing” “I want more information” “I want to enquire further” 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = moderately so, 4 = very much so) |

Kang et al. (2009) | (Single item) “Rate your level of curiosity on a scale from 1-7” |

Baranes et al. (2015) | (Single item) “Rate your level of curiosity on a scale from 1-5” |

Boykin and Harackiewicz (1981) | (Single item) “Indicate on a 13-point scale how interested you are in learning the correct answer to a question” |

Halamish et al. (2019) | (Single item) “Rate your level of curiosity of an answer to a question on a scale from 1-10” |

Ligneul et al. (2018) | (Single item) “Rate your level of curiosity of an answer to a question on a scale from 1-100” |

Lowry and Johnson (1981) | The authors employed two behavioral measures: (1) frequency of use of a special information station containing books, pictures, and filmstrips and (2) frequency of attendance of an optional film screening. |

The authors employed a behavioral measure: How long did children engage with the exploration of fish looking out of a window of a submarine? | |

Wu et al. (2018) | Activities undertaken in a laboratory were self-reported on a researcher-constructed 7-item scale. |

Appendix 2. Measures of Situational Interest 1988–2019

This appendix displays the various measures of situational interest in use in interest research. Potentially appropriate articles were found in a Web of Science search of articles published between 1988 and 2019. Criteria for inclusion were (1) whether the “situational interest” was found in either title or topic and (2) whether a measure of situational interest was reported in full detail. Initially, 398 articles were retrieved. Of these, 41 reported in sufficient detail one or more measures of epistemic curiosity.

Authors | Items |

Alexander et al. (1994a), Alexander et al. (1995), and Alexander et al. (1994b) | (Single item) “How interested are you …” 10-point Likert scale (1 = least interesting to 10 = most interesting). |

Chen and Darst (2002), Chen et al. (2001), Lin et al. (2019), Sun and Rueda (2012), and Yu et al. (2019) | (20 items) “I want to discover all the tricks in this activity” “I like to find out more about how to do it” “I want to analyse it to have a grasp on it” “I like to inquire into details of how to do it” “This activity is exciting” “It is an enjoyable activity to me” “This activity is appealing to me” “This activity inspires me to participate” “This is an exceptional activity” “I was concentrated” “I was focused” “I was very attentive all the time” “My attention was high” “This activity is complicated” “This is a complex activity” “It is hard for me to do this activity” “This activity is a demanding task” “This activity is new to me” “This is a new-fashioned activity for me to do” “This activity is fresh” 5-point Likert scale, (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). |

(Single item) “How much were you interested?” 4-point Likert scale (4 = highly interested, 3 = moderately interested, 2 = slightly interested, 1 = not interested). | |

Bhandari et al. (2019, Dousay (2016), Grund et al. (2019), Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. (2010), Linnenbrink-Garcia et al. (2013), and O’Keefe and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014) | (16 items) “I think the field of psychology is very interesting” “Psychology fascinates me” “I’m excited about psychology” “I think what we are learning in this course is important” “I think what we are studying in Introductory Psychology is useful for me to know” “I think the field of psychology is an important discipline” “To be honest, I just do not find psychology interesting” “I find the content of this course personally meaningful” “I think this class is interesting” “I see how I can apply what we are learning in Introductory Psychology to real life” “This class has been a waste of my time” “I do not like the lectures very much” “The lectures in this class aren’t very interesting” “I enjoy coming to lecture” “The lectures in this class really seem to drag on forever” “I like my instructor” “I am enjoying this psychology class very much” 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

(Example items) “When you think of the previous module’s sessions, to what extent did the sessions capture your attention?” “When you think of the previous module’s sessions, to what extent were the sessions exciting for you?” “When you think of the previous module’s sessions, to what extent did you find that the topics in the sessions matter to you?” “When you think of the previous module’s sessions, to what extent did you want to find out more about the topics in the sessions?” 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = very much). | |

Hong et al. (2019), Ribeiro et al. (2018), and Rotgans and Schmidt (2011, 2014, 2018) | (Five items) “I enjoy working on this topic” “I want to know more about this topic” “I think this topic is interesting” “I am fully focused on this topic; I am not distracted by other things” “Presently, I feel bored” 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all, 2 = not true for me, 3 = neutral, 4 = true for me, 5 = very true for me). |

Lentillon-Kaestner and Roure (2019); Roure et al. (2019a); Roure et al. (2019b); and Roure et al. (2016) | (Example items) “What we did today was new to me” “What we did was enjoyable” “I wanted to analyse and have a better grasp of what we were learning today” “What we were learning demanded a high level of attention” “What we were learning was hard to learn” 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). |

Dorfner et al. (2018) | (Single item) “The topic of today’s biology lessons was …” 4-point Likert scale (1 = very uninteresting, 2 = uninteresting, 3 = interesting, 4 = very interesting). |

Habig et al. (2018) | (8 items) “How interested you are in working on the following questions during chemistry lessons?” “Conducting experiments to analyse drinking water by following a given instruction” “Analysing drinking water more closely” “Drawing the design of an experiment regarding drinking water” “Telling other students something about the origins of our drinking water” “Organising a small investigation of water” “Selecting and organising information regarding our drinking water” “Talking about our drinking water with other students” 4-point Likert scale (1 = I am not interested at all, 2 = I am rather not interested, 3 = I am rather interested, 4 = I am very interested). |

Park (2015) | (Example items) “I felt active at the moment while I was studying” “I was completely caught up in what I was studying” “When learning from the material, I was concentrated” “I found something interesting at the beginning of this instructional material that got my attention” 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). |

Durik et al. (2015) | (3 items) “The left-to-right technique is interesting” “Using this multiplication technique is fun” “The learning program was enjoyable” 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). |

Magner et al. (2014) | (3 items) “I find the line drawing {with illustration} entertaining” “I find the line drawing {with illustration} important” 9-point Likert scale (1 = I totally disagree to 9 = I totally agree). |

(Single item) “Working on these tasks seems to be …” 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all interesting to 7 = very interesting). | |