Abstract

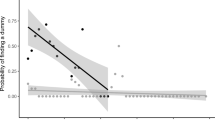

When considering the impact of wind turbines on the mortality of birds and bats, it is important to know the length of time that a carcass will be detectable. Thousands of small animals (such as many passerine birds with high mortality rates) die every day, but dead animals are rarely found by casual observers in the field. What is the fate of small carcasses in European ecosystems? During this project, we placed 120 defrosted day-old chicks (Gallus gallus f. domestica) as a model for a small carcass in a variety of habitats in southwestern Germany between the end of May and the beginning of December 2014. Using automatic trail cameras, we recorded the scavengers which visited the carrion or were feeding on it. Overall, two-thirds of the carcasses were removed under these conditions within a 5-day period. During the summer months, 20 % of the chicks were buried by burying beetles (Nicrophorus sp.), and 40 % were removed by nine mammal and three bird species. The most important vertebrate scavengers were the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), the Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo), the European Magpie (Pica pica) and the Domestic Cat (Felis catus). Among the scavenged chicks, 38.8 % vanished during the first 24 h of exposure. The median persistence time was 2.79 days. Persistence times were not dependent on habitat type, but carrion persisted longer on average in autumn than in summer. Knowledge of the factors influencing carcass persistence is important for estimating mortality in songbirds or bats in the context of wind turbines.

Zusammenfassung

Wer entsorgt tote Kleinvögel? Die Rolle von Totengräbern, Vögeln und Säugetieren in Südwestdeutschland Wenn man die Gefährdung von Vögeln und Fledermäusen durch Windkraftanlagen ermitteln möchte, muss man wissen, wie lange tote Tiere auffindbar bleiben. Im Projekt wurden von Ende Mai bis Anfang Dezember 2014 insgesamt 120 aufgetaute Eintagsküken in verschiedenen Lebensräumen in Südwestdeutschland mit Hilfe von automatischen Wildkameras überwacht. Insgesamt wurden zwei Drittel der ausgelegten Kadaver innerhalb von fünf Tagen entfernt. 20 % wurden von Totengräbern (Nicrophorus sp.) vergraben, wobei der Anteil im Jahresverlauf abnahm. 40 % der Küken wurden von insgesamt neun Säugetier- und drei Vogelarten gefressen. Unter den Wirbeltieren waren Rotfuchs (Vulpes vulpes), Mäusebussard (Buteo buteo), Elster (Pica pica) und Hauskatze (Felis catus) die wichtigsten Aasfresser. Über 38 % der ausgelegten toten Küken verschwand innerhalb der ersten 24 h. Der Median der Persistenzzeit betrug 2,79 d. Es konnte kein Zusammenhang zwischen Habitattypen und Persistenzzeiten festgestellt werden; die Küken blieben jedoch im Herbst im Durchschnitt länger liegen als im Sommer. Die Umgebungstemperatur kann in diesem Zusammenhang als wichtiger Faktor angesehen werden. Diese Erkenntnisse sind ein erster Schritt, um die Gefährdung von Singvögeln oder Fledermäusen an Windkraftanlagen besser einschätzen zu können.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Balcomb R (1986) Songbird carcasses disappear rapidly from agricultural fields. Auk 103:817–820

Braack LEO (1987) Community dynamics of carrion-attendant arthropods in tropical African woodland. Oecologia 72:402–409. doi:10.1007/BF00377571

DeVault TL, Brisbin I Jr, Lehr Rhodes Jr, Olin E (2004) Factors influencing the acquisition of rodent carrion by vertebrate scavengers and decomposers. Can J Zool 82:502–509. doi:10.1139/Z04-022

DeVault TL, Rhodes OE (2002) Identification of vertebrate scavengers of small mammal carcasses in a forested landscape. Acta Theriol 47:185–192. doi:10.1007/BF03192458

DeVault TL, Rhodes Jr, Olin E, Shivik JA (2003) Scavenging by vertebrates: behavioral, ecological, and evolutionary perspectives on an important energy transfer pathway in terrestrial ecosystems. Oikos 102:225–234. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12378.x

Dietz C, von Helversen O, Nill D (2009) Bats of Britain and Europe and Northwest Africa. A & C Black Publishers Ltd, London

Drewitt AL, Langston RH (2006) Assessing the impacts of wind farms on birds. Ibis 148:29–42. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00516.x

Hiraldo F, Blanco JC, Bustamante J (1991) Unspecialized exploitation of small carcasses by birds. Bird Study 38:200–207. doi:10.1080/00063659109477089

Janzen DH (1977) Why fruits rot, seeds mold, and meat spoils. Am Nat 111:691–713. doi:10.1086/283200

Jobin A, Molinari P, Breitenmoser U (2000) Prey spectrum, prey preference and consumption rates of Eurasian lynx in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Acta Theriol 45:243–252

Kostecke RM, Linz GM, Bleier WJ (2001) Survival of avian carcasses and photographic evidence of predators and scavengers. J Field Ornithol 72:439–447. doi:10.1648/0273-8570-72.3.439

Kuvlesky WP, Brennan LA, Morrison ML, Boydston KK, Ballard BM, Bryant FC (2007) Wind energy development and wildlife conservation: challenges and opportunities. J Wildl Manag 71:2487–2498. doi:10.2193/2007-248

Linz G, Davis JE Jr, Engeman RM, Otis DL, Avery ML (1991) Estimating survival of bird carcasses in cattail marshes. Wildl Soc Bull 19:195–199

Müller JK, Eggert AK (1987) Effects of carrion-independent pheromone emission by male burying beetles (Silphidae: Necrophorus). Ethology 76:297–304. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1987.tb00690.x

Niethammer G, Glutz von Blotzheim, Urs N, Bauer KM, Bezzel E (1979–1997) Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft; AULA, Wiesbaden

Prosser P, Nattrass C, Prosser C (2008) Rate of removal of bird carcasses in arable farmland by predators and scavengers. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 71:601–608. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.10.013

Pucek Z, Jędrzejewski W, Jędrzejewska B, Pucek M (1993) Rodent population dynamics in a primeval deciduous forest (Bialowieża National Park) in relation to weather, seed crop, and predation. Acta Theriol 38:199–232

Pukowski E (1933) Ökologische Untersuchungen an Necrophorus f. Z Morphol Okol Tiere 27:518–586. doi:10.1007/BF00403155

R Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing

Santos SM, Carvalho F, Mira A (2011) How long do the dead survive on the road? Carcass persistence probability and implications for road-kill monitoring surveys. PLoS One 6:e25383

Scott MP (1990) Brood guarding and the evolution of male parental care in burying beetles. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 26:31–39. doi:10.1007/BF00174022

Scott MP (1998) The ecology and behavior of burying beetles. Annu Rev Entomol 43:595–618. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.595

Selva N, Jędrzejewska B, Jędrzejewski W, Wajrak A (2005) Factors affecting carcass use by a guild of scavengers in European temperate woodland. Can J Zool 83:1590–1601. doi:10.1139/z05-158

Tobin ME, Dolbeer RA (1990) Disappearance and recoverability of song bird carcasses in fruit orchards. J Field Ornithol 61:237–242

Young A, Stillman R, Smith MJ, Korstjens AH (2014) An experimental study of vertebrate scavenging behavior in a Northwest European woodland context. J Forensic Sci 59:1333–1342. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.1246

Acknowledgments

We thank the community of Helmstadt-Bargen, the game tenants W. Zota, H. Edler and H. Gerstlauer, and the Angler Club Helmstadt-Bargen for permission to set up the cameras. We are also grateful to the Heidelberg Zoo for the opportunity to order a large quantity of day-old chicks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by T. Gottschalk.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Henrich, M., Tietze, D.T. & Wink, M. Scavenging of small bird carrion in southwestern Germany by beetles, birds and mammals. J Ornithol 158, 287–295 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1363-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1363-1