Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Individuals who had a low birthweight (LBW) are at an increased risk of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes when exposed to high-fat overfeeding (HFO). We studied genome-wide mRNA expression and DNA methylation in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) after 5 days of HFO and after a control diet in 40 young men, of whom 16 had LBW.

Methods

mRNA expression was analysed using Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays and DNA methylation using Illumina 450K BeadChip arrays.

Results

We found differential DNA methylation at 53 sites in SAT from LBW vs normal birthweight (NBW) men (false discovery rate <5%), including sites in the FADS2 and CPLX1 genes previously associated with type 2 diabetes. When we used reference-free cell mixture adjustments to potentially adjust for cell composition, 4,323 sites had differential methylation in LBW vs NBW men. However, no differences in SAT gene expression levels were identified between LBW and NBW men. In the combined group of all 40 participants, 3,276 genes (16.5%) were differentially expressed in SAT after HFO (false discovery rate <5%) and there was no difference between LBW men and controls. The most strongly upregulated genes were ELOVL6, FADS2 and NNAT; in contrast, INSR, IRS2 and the SLC27A2 fatty acid transporter showed decreased expression after HFO. Interestingly, SLC27A2 expression correlated negatively with diabetes- and obesity-related traits in a replication cohort of 142 individuals. DNA methylation at 652 CpG sites (including in CDK5, IGFBP5 and SLC2A4) was altered in SAT after overfeeding in this and in another cohort.

Conclusions/interpretation

Young men who had a LBW exhibit epigenetic alterations in their adipose tissue that potentially influence insulin resistance and risk of type 2 diabetes. Short-term overfeeding influences gene transcription and, to some extent, DNA methylation in adipose tissue; there was no major difference in this response between LBW and control participants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Overfeeding is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and may cause insulin resistance even before weight gain develops [1, 2]. Studies have consistently shown that individuals who had a low birthweight (LBW) due to a suboptimal fetal environment have higher risk of develo** metabolic diseases including type 2 diabetes [3, 4]. Additionally, young, healthy LBW men develop more severe peripheral insulin resistance when exposed to 5 days of high-fat overfeeding (HFO) compared with men with a normal birthweight (NBW) [1].

Lifestyle-related factors may alter epigenetic and transcriptional patterns [5–12], and thereby affect the risk of metabolic diseases. Indeed, we observed widespread DNA methylation changes in skeletal muscle from healthy young men after 5 days of HFO [7]; in contrast, there were no significant epigenetic changes in matched LBW men after HFO [13]. We also observed extensive DNA methylation changes in subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and skeletal muscle after regular exercise [10, 11]. However, genome-wide DNA methylation plasticity in response to overfeeding in human SAT has not been explored.

Several studies have suggested that insulin resistance is initiated in the adipose tissue and that this may induce insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and liver before the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes [14, 15]. Excess energy intake has unfavourable effects on whole-body insulin sensitivity independent of changes in body weight in both healthy lean [1, 16] and obese diabetic individuals [17]. Additionally, short- and long-term overfeeding may alter adipose tissue histology [18] and gene expression [18–21].

We hypothesised that transcriptional and epigenetic levels in SAT change with short-term HFO, and that the pattern and plasticity of these molecular modifications may be different in SAT from LBW vs NBW individuals, thereby potentially contributing to the metabolic differences seen in LBW individuals. Therefore, we examined the influence of 5 days of HFO on genome-wide mRNA expression and DNA methylation in SAT from 40 healthy young men, of whom 16 had a LBW and 24 were matched NBW controls. To replicate our epigenetic results in another cohort, we analysed DNA methylation in response to 7 weeks of overfeeding in SAT samples from another study.

Methods

Study participants and diets

HFO cohort

This study included 40 healthy young men recruited from the Danish National Birth Registry [22]. Sixteen men had a LBW (≤10th percentile) and 24 were age- and BMI-matched controls who had a NBW (≥50th percentile and ≤90th percentile). These individuals form part of a dietary challenge study which includes 46 individuals; their detailed clinical characteristics have been described [1, 16]. Using a randomised crossover design, each participant received an individualised weight-maintaining 3-day control diet (35% of energy from fat) and a 5-day HFO diet (50% more energy, 60% of energy from fat) prior to clinical examination and SAT biopsy excision [16]. The diets were separated by a washout period of 6–8 weeks. The local ethics committee approved the study [22].

All individuals underwent a 3 h hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp to estimate hepatic and peripheral insulin sensitivities [22] and the HOMA-IR was calculated [23]. Abdominal SAT biopsies were excised under local anaesthesia both during fasting and after insulin stimulation; these were frozen in liquid nitrogen within 30 s.

Twin cohort

A total of 142 elderly monozygotic and dizygotic twins were included for replication of SAT gene expression analysis. Their clinical characterisation and SAT biopsies were performed as part of a larger study [24].

LIPOGAIN cohort

Seventeen healthy young individuals from another diet intervention study were included for replication of overfeeding-induced DNA methylation changes in SAT [20]. Abdominal SAT biopsies were excised at baseline and after 7 weeks of overfeeding in which muffins high in saturated fatty acids were added to the habitual diet.

Genome-wide mRNA expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted from SAT using miRNeasy MiniKits and purified from small RNA molecules with RNeasy MiniElute Cleanup Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA quality was assessed (RNA integrity number: mean, 8.3; range, 6.8–9.0) using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Basel, Switzerland). The expression of 28,829 transcripts representing 19,880 genes was analysed using GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) following the Affymetrix protocol. Data were background-corrected and quantile-normalised with a robust multiarray average (‘RMA’) approach using dedicated Bioconductor software [25].

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from SAT using QIAamp DNA Micro Kits (Qiagen; HFO cohort) and DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (Qiagen; LIPOGAIN cohort). DNA (500 ng) was bisulphite converted using EZ DNA Methylation Kits (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) and DNA methylation of 485,577 cytosines covering 21,231 genes was analysed with Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip arrays (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) [26] according to the Infinium Protocol (User Guide part #15019519; HFO and LIPOGAIN cohorts). Paired samples (control and overfeeding) were placed on the same chip, and samples from LBW and NBW individuals were evenly distributed (see electronic supplementary material [ESM] Methods).

Technical validation by quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was used to analyse the mRNA expression of five genes in SAT from all men for whom cDNA was available (HFO cohort; see ESM Methods).

Statistical analysis

Overfeeding-induced expression and methylation changes were analysed using paired Wilcoxon tests (i.e. for HFO vs the control diet) based on the randomised crossover design [1, 16]. Similarly, paired Wilcoxon tests were used to analyse overfeeding-induced DNA methylation changes in the LIPOGAIN cohort. Comparisons between birthweight groups were made using two-sample Mann–Whitney tests. To account for multiple testing, we applied Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction; a q value of <0.05 was considered significant. In addition to these tests, methylation data were adjusted for potential differences in cell mixture using the reference-free adjustment method recently developed by Houseman et al [27]. Here, we also adjusted for age, BMI and, for paired comparisons, birthweight. Random-effect linear models (PROC MIXED) in the twin cohort were adjusted for sex, age and, where appropriate, BMI using SAS Enterprise Guide (version 6.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). This model adjusts for twin pair membership (a random-effects term) and zygosity (a fixed-effects term). According to a post hoc power calculation, we had 95% power to detect an absolute DNA methylation difference of 2% (SD 1.5%) in 16 LBW vs 18 NBW participants.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The men who had a LBW were shorter, had higher fasting glucose levels and were more insulin resistant based on HOMA-IR compared with NBW men (ESM Table 1). Peripheral insulin sensitivity and fasting levels of insulin, NEFA and triacylglycerols were not significantly different between the LBW and NBW groups during control diet feeding.

The clinical response of the 40 men to HFO is presented in Table 1. After 5 days of HFO, fasting levels of glucose and insulin were significantly increased, resulting in an elevated HOMA-IR. Hepatic insulin resistance increased and peripheral insulin sensitivity showed a tendency to decrease (p = 0.06). Fasting NEFA, triacylglycerol and VLDL-cholesterol levels were significantly lower and insulin-stimulated NEFA levels were higher after HFO than after the control diet (Table 1).

Impact of birthweight on gene expression and DNA methylation in SAT

After correction for multiple testing (q < 0.05), we found no significant differences in genome-wide SAT expression between LBW and NBW men during the control diet or after HFO. However, we found 13 cytosine–phosphate–guanine (CpG) sites during the control diet and 40 other sites after the HFO that had differential DNA methylation levels in 16 LBW compared with 18 NBW men (q < 0.05; Table 2), including sites in the ACAT1, CPLX1, FADS2, GPRC5B, HCCA2 and IGF2R genes that have previously been associated with type 2 diabetes (ESM Table 2). The known or suspected general function and the potential diabetes-related function of all differentially methylated genes are presented in ESM Table 2. Five of the 13 sites with significant between-group differences under control diet conditions were also differentially methylated after HFO (p < 0.05). Likewise, nine of the 40 sites that were significantly different between birthweight groups during HFO were also differentially methylated during the control diet (Table 2). We investigated the DNA methylation response to HFO separately in LBW and NBW men and found no significant changes in either group.

Changes in SAT expression in response to HFO

Since there were no significant differences in mRNA expression between LBW and NBW men, the impact of 5 days of HFO on SAT gene expression was examined in both groups combined.

Interestingly, expression of 12.9% (3,713) of all analysed transcripts and 16.5% (3,276) of all analysed genes was significantly changed in SAT after the HFO compared with the control diet (q < 0.05; ESM Table 3): of these transcripts, 59% (2,207) were upregulated and 41% (1,506) were downregulated. Genes with the most pronounced increase (including ELOVL6, FADS2, NNAT and DGAT2) and decrease (including SLC27A2 and CIDEA) in transcription are presented in Table 3. A total of 1,469 (40%) of the genes that showed significant differences in expression changed more than 10% (ESM Table 3).

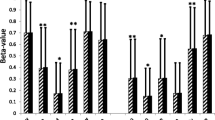

We used Webgestalt (http://bioinfo.vanderbilt.edu/webgestalt) to test whether functionally related genes were systematically altered with HFO. Significantly upregulated transcripts could be mapped to 40 Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways that predominantly related to metabolism and energy metabolism (Fig. 1a, ESM Table 4). Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS; Fig. 1b–f), citrate cycle and pyruvate metabolism were the most significant KEGG pathways among transcripts that were upregulated by HFO. Moreover, many genes involved in the fatty acid metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids pathways were upregulated by HFO (Fig. 2a–c).

Gene sets and OXPHOS genes with significantly increased mRNA expression in SAT after 5 days of HFO in all men (n = 40). (a) Twelve of the most significantly enriched KEGG pathways representing the genes with increased expression after HFO. Black bars, observed number of genes; white bars, expected number of genes; number in parenthesis, total number of genes in each pathway. q < 0.05 vs the expected number of genes (after Benjamini–Hochberg FDR correction). (b–f) Genes in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway that are significantly upregulated with HFO (black bars) compared with the control diet (white bars). (b–f) Genes in OXPHOS complexes are shown separately: (b) I, (c) II, (d) III, (e) IV and (f) V. † q < 0.05 (after FDR correction) vs the control diet. AU, arbitrary unit; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; TCA, tricarboxylic acid

Metabolically important genes with differential mRNA expression in SAT with 5 days of HFO (black bars) compared with the control diet (white bars) (n = 40). (a–c) Significantly upregulated genes in the (a) fatty acid metabolism, (b) glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and (c) biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids KEGG pathways. (d–f) Selected genes in the (d) insulin signalling KEGG pathway and (e) adipokines and (f) adipogenesis-specific transcription factors that were significantly up- or downregulated after 5 days of HFO. † q < 0.05 (after FDR correction) vs the control diet

TGF-beta signalling was the only significantly enriched KEGG pathway among transcripts that were downregulated by HFO (ESM Table 5). Notably, genes in the insulin signalling pathway were either upregulated (27 genes) or downregulated (16 genes; ESM Tables 3 and 4): downregulated genes included INSR and IRS2; and upregulated genes included AKT1, AKT2, IRS1 and SLC2A4 (also known as GLUT4; Fig. 2d). A literature search was done to investigate whether genes of potential importance in adipose tissue were differentially expressed with HFO. We found that several adipose-derived hormones (adipokines) [14] and adipogenesis-induced transcription factors [28] were up- or downregulated by HFO (Fig. 2e, f). Moreover, two white adipose tissue markers (HOXC8, HOXC9) that are downregulated in human brown adipose tissue [29] were upregulated by HFO (ESM Table 3).

Comparison with mRNA data from other overfeeding studies

We found a large overlap in the transcriptional response to overfeeding in SAT between our HFO study and two previous short-term (7–14 days) overfeeding studies (ESM Table 6) [18, 19].

Technical validation of gene expression microarray data

There were significant correlations between microarray and qPCR expression data for all tested genes (CIDEA, ELOVL6, FADS2, GYS2 and SLC27A2) and significant changes in HFO-induced mRNA expression (up- or downregulation) identified with the microarray were confirmed by qPCR (ESM Table 7).

Replication of SLC27A2 expression in SAT

SLC27A2 encodes FATP-2 which functions as both a fatty acid transporter and an acyl-CoA synthetase that drives fatty acid uptake by trap** activated fatty acids (acyl-CoA esters) inside the cell [30]. We used qPCR to analyse SLC27A2 expression in SAT obtained during fasting and after hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamps to gain insight into in vivo regulation of this gene. SLC27A2 expression was lower in SAT biopsies obtained after the HFO compared with the control diet under both fasting and insulin-stimulated conditions (Fig. 3a–c). Moreover, hyperinsulinaemia reduced SLC27A2 expression during the control diet but not during HFO (ESM Fig. 1a, b).

Overfeeding-induced mRNA expression and DNA methylation changes in genes important for metabolism and insulin resistance, and the impact of LBW on DNA methylation in SAT. (a–c) Impact of 5 days of HFO on SLC27A2 mRNA expression in SAT. (a) Fold changes in SLC27A2 mRNA expression for each of the 40 men (Affymetrix arrays). (b, c) Fold changes in SLC27A2 mRNA expression as measured by qPCR for (b) 14 fasting men and (c) 10 hyperinsulinaemic men. ***p < 0.001 vs the control diet. (d–g) Selected genes previously linked to adipose tissue metabolism and/or differentiation that showed differential DNA methylation (HFO and LIPOGAIN cohorts) and mRNA expression (HFO cohort) levels after overfeeding (black bars) compared with the control diet (white bars). *p < 0.05 and † q < 0.05 (FDR correction) vs the control diet. (h) CpG sites with the largest differences (of >10% during both control diet and HFO) in SAT methylation between NBW (white bars) and LBW (grey bars) men after reference-free cell mixture adjustment. † q < 0.05 (FDR correction) vs NBW. Ins stim, insulin stimulated

To obtain further insight into the biological role of SLC27A2, we analysed expression of this gene in SAT biopsies from 142 elderly monozygotic and dizygotic twins with a broad range of BMIs (17–39 kg/m2) and different glucose tolerance statuses (ESM Table 8). SLC27A2 expression did not differ between sexes (p = 0.87) or between diabetic and non-diabetic individuals (p = 0.38; ESM Fig. 2a, b). However, SLC27A2 mRNA expression correlated negatively with several diabetes- and obesity-related traits (i.e. fasting glucose, fasting insulin, insulin resistance, BMI, WHR and triacylglycerol levels; ESM Table 9). We subsequently measured Spearman’s correlation coefficients between SLC27A2 expression and clinical characteristics in the HFO cohort. In this analysis, SLC27A2 expression also correlated negatively with obesity- and diabetes-related traits such as BMI, HOMA-IR and plasma leptin levels during both diets (ESM Fig. 3a–d, ESM Table 9).

Changes in SAT DNA methylation in response to HFO

To investigate the effect of 5 days of HFO on the SAT epigenome, DNA methylation at 461,368 cytosines was analysed in SAT from 18 NBW and 16 LBW men after each diet. In all, methylation was significantly changed at 21,881 sites with HFO (p < 0.05; ESM Table 10). However, no individual methylation site had a q value of <0.05 after FDR correction.

We then merged data on genes with significant alterations in both mRNA expression (3,276 genes) and DNA methylation (p < 0.05). Here, the methylation level at 3,102 sites covering 1,648 genes changed with HFO (p < 0.05; ESM Table 11). Interestingly, the most significantly enriched gene sets among genes with both altered methylation and mRNA expression after HFO were mapped to the oxidative phosphorylation (34 genes) and insulin signalling (36 genes) KEGG pathways (ESM Table 12).

Epigenetic modifications can regulate gene expression [31]; therefore, we measured Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r values) between mRNA and DNA methylation levels for genes that changed both their mRNA expression (q < 0.05) and DNA methylation status (p < 0.05) in SAT with HFO. Although negative or positive correlations with a p value of <0.05 were identified for 213 CpG methylation–mRNA expression combinations, none had a q value of <0.05 after FDR correction (ESM Table 13).

Replication of DNA methylation changes

To biologically replicate our DNA methylation findings from the HFO cohort in another cohort, we analysed genome-wide DNA methylation in SAT samples from 17 young individuals from the LIPOGAIN study in whom 7 weeks of overfeeding caused increased weight, BMI and HDL levels (ESM Table 14). We found 541 sites with increased and 111 sites with decreased methylation after overfeeding that were common to both cohorts (p < 0.05; ESM Table 15). Of the genes with DNA methylation changes in both cohorts, 112 were also differentially expressed (q < 0.05). These included CDK5, CIDEA, IGFBP5 and SLC2A4, which were previously linked to adipose tissue metabolism and/or differentiation (Fig. 3d–g, ESM Table 16).

Impact of HFO on enzymes regulating DNA methylation

To further dissect the mechanism controlling how overfeeding may alter DNA methylation in SAT, we investigated the expression of genes encoding proteins that are important for regulating DNA methylation. DNMT1 and genes encoding enzymes and modifiers involved in one-carbon metabolism and the generation of methyl donors were among the genes with altered expression after HFO (ESM Table 17).

Impact of birthweight and HFO on DNA methylation in SAT after reference-free cell mixture adjustment

Adipose tissue contains several different cell types, including adipocytes, fibroblasts, stem cells and immune cells. Therefore, differences in the cellular composition may affect the overall DNA methylation pattern in adipose tissue. Using data on genome-wide DNA methylation patterns measured in purified cell types, one may perform cell mixture adjustments when studying DNA methylation in tissues and/or mixed cell populations. However, no such data currently exist for purified cells from adipose tissue. Instead, we used a reference-free cell mixture adjustment method recently developed by Houseman et al [27] to potentially adjust our methylation data for differences in cell mixture. Using this method, methylation at 27,999 sites during control diet and 31,866 sites during HFO was found to significantly differ in SAT from LBW vs NBW men (q < 0.05; ESM Table 18), including all 53 CpG sites that showed significant differences before cell admixture adjustment (Table 2). Of these, 4,323 sites annotated to 2,448 genes differed significantly between LBW and NBW men under both control diet and HFO conditions (q < 0.05; ESM Table 19). These included 13 out of the 14 CpG sites that had methylation differences during both diets before adjustment, including CPLX1 and FADS2 (Table 2). The largest identified differences in SAT methylation between LBW and NBW men are presented in Fig. 3h. Moreover, we performed a pathway analysis on the 2,448 unique genes and found significant enrichment of genes in, for example, the protein digestion and absorption, endocytosis and calcium signalling pathways (ESM Table 20).

Finally, after reference-free cell mixture adjustment, SAT methylation at 1,009 sites annotated to 824 genes was significantly different under HFO vs control diet conditions (q < 0.05; ESM Table 21). These include 937 of the sites presented in ESM Table 10, including sites in CIDEA, KLF14 and PRDM16.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that LBW individuals display multiple DNA methylation alterations in SAT in early adulthood. We also demonstrate that 5 days of a high-fat high-energy diet changes the expression of more than 3,000 genes in SAT from young men with or without a LBW. These changes may contribute to development of the insulin resistance seen in these men. In contrast to the transcriptome, only modest DNA methylation changes were observed in SAT in response to overfeeding.

A LBW affects key metabolic functions in multiple tissues, thereby increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes [4, 32]. This might partly be due to an adverse intrauterine environment that causes epigenetic alterations during fetal development. Interestingly, we found significant differences in DNA methylation at 53 sites in SAT from LBW vs NBW men either during control diet or HFO. Of these, 14 sites were significantly changed during both diets, including sites in FADS2 that has been genetically linked to type 2 diabetes [33] and in CPLX1 which has been associated with glucose-stimulated insulin release [34]. Moreover, sites in HCCA2 and IGF2R (which have also been genetically associated with type 2 diabetes) and in ACAT1 and GPRC5B (for which adipose tissue expression has been associated with insulin resistance and diabetes; see ESM Table 2) were differentially methylated in LBW men. Although the DNA methylation differences observed between LBW and NBW individuals may appear small, ageing might induce bigger differences that may, by influencing mRNA expression, become functionally significant and thus represent key defects involved in the development of type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, when reference-free cell mixture adjustments were performed according to Houseman et al [27], many more epigenetic alterations were identified under both dietary conditions in LBW vs NBW men. Importantly, these include the majority of the sites that differed between groups during both diets when methylation data were analysed without reference-free cell admixture adjustment. These included sites in CPLX1 and FADS2, as well as sites annotated to genes involved in, for example, protein digestion and absorption, endocytosis, and calcium signalling pathways. Nevertheless, it remains to be tested whether the adipose tissue cell composition differs between the LBW and NBW groups. In addition, the Houseman method uses mathematical modelling to adjust in silico for cell composition and other ‘unknown’ variables that might affect the data. To our knowledge, no other studies have applied this reference-free method in adipose tissue or investigated whether it generates consistent results in this tissue.

The altered transcriptional activity of SAT after 5 days of HFO included upregulation of numerous genes involved in energy metabolism. Previous short-term overfeeding studies mainly found SAT transcriptional changes in genes involved in lipid [18, 19] and carbohydrate metabolism [19]. Despite the excess lipid content of the HFO diet compared with the control diet [16], we found that genes upregulated by HFO were enriched in many (10 out of 15) of the KEGG pathways related to carbohydrate metabolism, but only to a few (4 out of 17) of the KEGG pathways related to lipid metabolism (www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html). Interestingly, several genes involved in de novo lipogenesis (e.g. ACLY, ACACA, FASN, FADS1, FADS2 and SCD) were upregulated in SAT in both this and a previous overfeeding study [21]. An induction of adipose tissue lipogenesis (rather than hepatic lipogenesis) could mirror an increased efficiency of lipid storage during HFO, as reflected by the reduced fasting plasma NEFA and triacylglycerol levels observed in the young men after HFO. Moreover, the finding that genes involved in glycogen synthesis (GYS1 and GYS2) were among those most strongly upregulated by HFO is consistent with the suggestion that adipose glycogen turnover may help coordinate glucose and lipid metabolism in adipose tissue [35].

Six of the 12 most strongly upregulated transcripts are key genes in lipid and glycogen metabolism: ACLY, DGAT2, ELOVL6, FADS2, GYS2 and SCD. Interestingly, we recently found that ELOVL6, FADS1, FADS2 and GYS2 are among the most strongly downregulated genes in SAT from monozygotic twins discordant for type 2 diabetes [9]. In addition, the gene sets that were most significantly upregulated by HFO in this study (oxidative phosphorylation, citrate cycle and pyruvate metabolism) were significantly downregulated in SAT from diabetic twins [9]. A disturbed adipocyte metabolism has been suggested to shift lipid storage into alternative tissues, such as skeletal muscle, the liver and the pancreas, resulting in insulin resistance [36]. Our data suggest that low mRNA levels or an inability to upregulate these genes during HFO may predispose individuals to type 2 diabetes.

Changes in the expression of several genes involved in insulin-signalling occurred in response to HFO: for example, INSR, IRS2 and PIK3CB were downregulated; and AKT1, AKT2, IRS1 and SLC2A4 (encoding GLUT4) were upregulated. To our knowledge, the opposing effects of HFO-induced regulation on IRS1 and IRS2 (which encode important docking proteins) in SAT has not been previously observed.

Interestingly, expression of the most strongly downregulated gene, SLC27A2, showed inverse correlations with diabetes and obesity-related traits including insulin resistance and BMI. This indicates that transcriptional regulation of SLC27A2 may be important in HFO-induced pathogenesis of insulin resistance and obesity. The encoded protein, very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (VLACS; also known as FATP-2) preferentially mediates the transport and conversion of long-chain and very-long-chain n-3 fatty acids into the corresponding n-3 acyl-CoAs, which are trafficked into pools destined for phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylinositol incorporation [30, 37]. In line with our data, previous studies show SLC27A2 downregulation in human SAT after 56 days of overfeeding [18] and after in vitro exposure to adipocytokines such as TNF-α and leptin [38]. A link between inflammation, SLC27A2 regulation and insulin resistance has been proposed [38]. This is supported by another study in which SLC27A2 expression was lower in SAT from insulin-resistant vs insulin-sensitive women [39]. Interestingly, we found both upregulation (AGT, RBP4, TNF) and downregulation (CFD, IL6, NAMPT) of genes encoding adipokines and cytokines, which may contribute to HFO-induced insulin resistance. Furthermore, based on data from this and previous studies [30, 37], we speculate that diet-induced downregulation of SLC27A2 may influence insulin resistance through reduced channelling of specific lipids (e.g. n-3 fatty acids) toward phosphatidylinositol synthesis, which could subsequently reduce phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signalling and other insulin-signalling events downstream of AKT [40]. As SLC27A2 expression was reduced by hyperinsulinaemia, the SLC27A2 downregulation observed during HFO may be partly caused by increased insulin levels.

Some of the significant changes in gene expression in response to HFO were modest, and one may question whether such changes are of biological importance. However, small changes in the expression of numerous genes involved in key metabolic pathways may indeed have biological effects [41, 42]. Importantly, we technically validated our microarray data on all five analysed genes using qPCR. Additionally, the overlap in SAT gene expression data between our study and previous short-term overfeeding studies further supports the biological significance of our data [18, 19]. Nevertheless, small changes in gene expression should be interpreted cautiously. In addition, changes in cell type composition could be responsible for some of the changes in HFO-induced gene expression. However, when we investigated 24 cell-type-specific markers for adipocytes, pre-adipocytes, brown adipocytes, macrophages, cytokines and inflammation [12], only LEP, TNF (cytokines) and CIDEA (brown adipocyte marker) were differentially expressed after HFO. These data suggest that 5 days HFO does not alter the cellular composition of SAT.

Although 5 days of HFO altered the expression of more than 3,000 genes in SAT, the associated epigenetic changes were less extensive. We previously found HFO-induced DNA methylation changes in PPARGC1A (in both SAT and skeletal muscle) [5, 6] and extensive genome-wide DNA methylation changes in skeletal muscle from NBW but not LBW men [7, 13]. Thus, our data show that epigenetic changes in SAT are less pronounced than in skeletal muscle [7] in response to 5 days of HFO. However, our overfeeding-induced methylation changes were replicated at more than 600 sites in SAT from a different cohort [20]. Most of these sites showed increased methylation levels during overfeeding, consistent with increased expression of the DNMT1 methyltransferase with HFO. The expression of several genes with altered DNA methylation in both overfeeding cohorts also changed with HFO including CDK5 and SLC2A4, whose protein activity and gene expression in adipose tissue were previously associated with insulin resistance [43, 44]. Finally, the results generated after reference-free cell mixture adjustment support the hypothesis that epigenetic changes take place in response to overfeeding.

It should be noted that we previously identified extensive epigenetic alterations in human adipose tissue from other cohorts of a similar size to the one included in this study [9, 11]. These studies together with our post hoc power calculation suggest an appropriate statistical power in the present study. Importantly, however, the stringent correction for multiple testing of our genome-wide data together with the modest epigenetic changes may have increased the risk of false negatives. Moreover, because the 450K BeadChip only covers ∼2% of genomic CpG sites, we cannot exclude the possibility that methylation changes occur at other genomic sites. Finally, a longer diet intervention may be required to induce more pronounced epigenetic changes in human SAT.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that young healthy men with a LBW exhibit multiple DNA methylation alterations in adipose tissue which may contribute to their increased risk of type 2 diabetes. However, SAT gene expression was similar in LBW and NBW men. We also demonstrated that 5 days of HFO causes extensive gene expression and modest epigenetic changes in SAT, with no differences in the responses of LBW and NBW men. Overall, this study adds to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms in adipose tissue that are likely to contribute to the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in people with and without LBW when exposed to overfeeding.

Abbreviations

- CpG:

-

Cytosine–phosphate–guanine

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- HFO:

-

High-fat overfeeding

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LBW:

-

Low birthweight

- NBW:

-

Normal birthweight

- OXPHOS:

-

Oxidative phosphorylation

- qPCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- SAT:

-

Subcutaneous adipose tissue

References

Brons C, Jacobsen S, Hiscock N et al (2012) Effects of high-fat overfeeding on mitochondrial function, glucose and fat metabolism, and adipokine levels in low-birth-weight subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302:E43–E51

Cornier MA, Bergman BC, Bessesen DH (2006) The effects of short-term overfeeding on insulin action in lean and reduced-obese individuals. Metabolism 55:1207–1214

Li Y, Ley SH, Tobias DK et al (2015) Birth weight and later life adherence to unhealthy lifestyles in predicting type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ 351:h3672

Whincup PH, Kaye SJ, Owen CG et al (2008) Birth weight and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA 300:2886–2897

Brons C, Jacobsen S, Nilsson E et al (2010) Deoxyribonucleic acid methylation and gene expression of PPARGC1A in human muscle is influenced by high-fat overfeeding in a birth-weight-dependent manner. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3048–3056

Gillberg L, Jacobsen SC, Ronn T, Brons C, Vaag A (2014) PPARGC1A DNA methylation in subcutaneous adipose tissue in low birth weight subjects—impact of 5 days of high-fat overfeeding. Metabolism 63:263–271

Jacobsen SC, Brons C, Bork-Jensen J et al (2012) Effects of short-term high-fat overfeeding on genome-wide DNA methylation in the skeletal muscle of healthy young men. Diabetologia 55:3341–3349

Kirchner H, Osler ME, Krook A, Zierath JR (2013) Epigenetic flexibility in metabolic regulation: disease cause and prevention? Trends Cell Biol 23:203–209

Nilsson E, Jansson PA, Perfilyev A et al (2014) Altered DNA methylation and differential expression of genes influencing metabolism and inflammation in adipose tissue from subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 63:2962–2976

Nitert MD, Dayeh T, Volkov P et al (2012) Impact of an exercise intervention on DNA methylation in skeletal muscle from first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 61:3322–3332

Ronn T, Volkov P, Davegardh C et al (2013) A six months exercise intervention influences the genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in human adipose tissue. PLoS Genet 9:e1003572

Ronn T, Volkov P, Gillberg L et al (2015) Impact of age, BMI and HbA1c levels on the genome-wide DNA methylation and mRNA expression patterns in human adipose tissue and identification of epigenetic biomarkers in blood. Hum Mol Genet 24:3792–3813

Jacobsen SC, Gillberg L, Bork-Jensen J et al (2014) Young men with low birthweight exhibit decreased plasticity of genome-wide muscle DNA methylation by high-fat overfeeding. Diabetologia 57:1154–1158

Ouchi N, Parker JL, Lugus JJ, Walsh K (2011) Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol 11:85–97

Smith U (2002) Impaired (‘diabetic’) insulin signaling and action occur in fat cells long before glucose intolerance—is insulin resistance initiated in the adipose tissue? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26:897–904

Brons C, Jensen CB, Storgaard H et al (2009) Impact of short-term high-fat feeding on glucose and insulin metabolism in young healthy men. J Physiol 587:2387–2397

Kelley DE, Wing R, Buonocore C, Sturis J, Polonsky K, Fitzsimmons M (1993) Relative effects of calorie restriction and weight loss in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 77:1287–1293

Alligier M, Meugnier E, Debard C et al (2012) Subcutaneous adipose tissue remodeling during the initial phase of weight gain induced by overfeeding in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E183–E192

Shea J, French CR, Bishop J et al (2009) Changes in the transcriptome of abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue in response to short-term overfeeding in lean and obese men. Am J Clin Nutr 89:407–415

Rosqvist F, Iggman D, Kullberg J et al (2014) Overfeeding polyunsaturated and saturated fat causes distinct effects on liver and visceral fat accumulation in humans. Diabetes 63:2356–2368

Franck N, Gummesson A, Jernas M et al (2011) Identification of adipocyte genes regulated by caloric intake. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E413–E418

Brons C, Jensen CB, Storgaard H et al (2008) Mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle is normal and unrelated to insulin action in young men born with low birth weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3885–3892

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Poulsen P, Grunnet LG, Pilgaard K et al (2009) Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in elderly twins. Diabetes 58:1350–1355

Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F et al (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249–264

Bibikova M, Barnes B, Tsan C et al (2011) High density DNA methylation array with single CpG site resolution. Genomics 98:288–295

Houseman EA, Molitor J, Marsit CJ (2014) Reference-free cell mixture adjustments in analysis of DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics 30:1431–1439

Leff T, Granneman JH (2010) Adipose tissue in health and disease. Wiley-VCH Verlag, Weinheim

Jespersen NZ, Larsen TJ, Peijs L et al (2013) A classical brown adipose tissue mRNA signature partly overlaps with brite in the supraclavicular region of adult humans. Cell Metab 17:798–805

Melton EM, Cerny RL, Watkins PA, DiRusso CC, Black PN (2011) Human fatty acid transport protein 2a/very long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (FATP2a/Acsvl1) has a preference in mediating the channeling of exogenous n-3 fatty acids into phosphatidylinositol. J Biol Chem 286:30670–30679

Jones PA (2012) Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 13:484–492

Pilgaard K, Faerch K, Carstensen B et al (2010) Low birthweight and premature birth are both associated with type 2 diabetes in a random sample of middle-aged Danes. Diabetologia 53:2526–2530

Yao M, Li J, **e T et al (2015) Polymorphisms of rs174616 in the FADS1-FADS2 gene cluster is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in northern Han Chinese people. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 109:206–212

Abderrahmani A, Niederhauser G, Plaisance V et al (2004) Complexin I regulates glucose-induced secretion in pancreatic beta-cells. J Cell Sci 117:2239–2247

Markan KR, Jurczak MJ, Allison MB et al (2010) Enhanced glycogen metabolism in adipose tissue decreases triglycerideride mobilization. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299:E117–E125

Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A (2010) Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome—an allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801:338–349

Melton EM, Cerny RL, DiRusso CC, Black PN (2013) Overexpression of human fatty acid transport protein 2/very long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (FATP2/Acsvl1) reveals distinct patterns of trafficking of exogenous fatty acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 440:743–748

Lappas M (2014) Effect of pre-existing maternal obesity, gestational diabetes and adipokines on the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism in adipose tissue. Metabolism 63:250–262

Soronen J, Laurila PP, Naukkarinen J et al (2012) Adipose tissue gene expression analysis reveals changes in inflammatory, mitochondrial respiratory and lipid metabolic pathways in obese insulin-resistant subjects. BMC Med Genomics 5:9

Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR (2006) Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 7:85–96

Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF et al (2003) PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 34:267–273

Olsson AH, Yang BT, Hall E et al (2011) Decreased expression of genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation in human pancreatic islets from patients with type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol 165:589–595

Choi JH, Banks AS, Estall JL et al (2010) Anti-diabetic drugs inhibit obesity-linked phosphorylation of PPARgamma by Cdk5. Nature 466:451–456

Kouidhi S, Berrhouma R, Rouissi K et al (2013) Human subcutaneous adipose tissue Glut 4 mRNA expression in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol 50:227–232

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Modest and L. S. Koch from the Steno Diabetes Center, Gentofte, Denmark, for excellent assistance in the laboratory, the Swegene Centre for Integrative Biology at Lund University, Sweden, for analysing gene expression and DNA methylation, and the young men for their participation in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Region Skåne, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, a European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/Lilly Research Fellowship, the Söderberg Foundation, The Swedish Diabetes Foundation, the Påhlsson Foundation, EXODIAB, a Linné grant (no. B31 5631/2006), The Danish Strategic Research Council, The Danish Council for Independent Research, the Rigshospitalet, the University of Copenhagen, the Steno Diabetes Center and the Danish Diabetes Academy.

Duality of interest statement

AV, CB and LGG are shareholders in Novo Nordisk A/S and AV is the recipient of honoraria for talks from Novo Nordisk A/S. All other authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Contribution statement

CB, AV and CL designed the study; LG, CB and MT conducted the research; FR, DI, ID and UR designed the study and/or collected data from the LIPOGAIN study; LG, AP, MT, LGG, PV, TR and EN analysed the data; and LG wrote the paper and is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Methods

(PDF 86 kb)

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 87 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

(PDF 135 kb)

ESM Fig. 3

(PDF 153 kb)

ESM Table 1

(PDF 80 kb)

ESM Table 2

(XLSX 18 kb)

ESM Table 3

(XLSX 319 kb)

ESM Table 4

(PDF 55 kb)

ESM Table 5

(PDF 20 kb)

ESM Table 6

(PDF 79 kb)

ESM Table 7

(PDF 189 kb)

ESM Table 8

(PDF 92 kb)

ESM Table 9

(PDF 108 kb)

ESM Table 10

(XLSX 1.64 mb)

ESM Table 11

(XLSX 418 kb)

ESM Table 12

(PDF 39 kb)

ESM Table 13

(XLSX 32 kb)

ESM Table 14

(PDF 77 kb)

ESM Table 15

(XLSX 99 kb)

ESM Table 16

(XLSX 38 kb)

ESM Table 17

(PDF 19 kb)

ESM Table 18

(XLSX 5.86 mb)

ESM Table 19

(XLSX 874 kb)

ESM Table 20

(PDF 27 kb)

ESM Table 21

(XLSX 138 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gillberg, L., Perfilyev, A., Brøns, C. et al. Adipose tissue transcriptomics and epigenomics in low birthweight men and controls: role of high-fat overfeeding. Diabetologia 59, 799–812 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3852-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3852-9