Abstract

Compulsory education in China refers to the mandatory, free, and universal education that all school-age children and teenagers receive, which includes six-year elementary school and three-year junior secondary school (middle school). Nine-year compulsory education in China is of great significance because it is closely associated with the healthy growth of hundreds of millions of children, the development of the country, and the future of the nation. This chapter focuses on the latter stage of compulsory education in China, namely the three-year junior secondary education (middle school), and attempts to present the educational landscape by including both quantitative and qualitative information in seven different sections. This chapter first provides an introduction of compulsory education and junior secondary education in China; then it highlights important education data of China in an international context. The third section proposes representative indicators to reflect the excellence level of junior secondary education for China and the world. The next two sections share best practices in the development of junior secondary education and inspiring stories of educators in this sector. It then reviews the latest literature and research focus on the field of junior secondary education. Lastly, the chapter outlines key policy documents on develo** junior secondary education. In general, Chinese government has been striving to facilitate the well and balanced development of junior secondary education. Significant progress has been made over the years, yet aspects that should be improved and strengthened are also discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Junior secondary education

- Well-rounded education (Suzhi education)

- High-quality and well-development

- Core competencies

1 Introduction

1.1 Compulsory Education in China

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the low literacy rate had been plaguing the country. According to statistics, over 80% of the population in China was illiterate in 1949, with illiteracy rates in rural areas exceeding 95% (Cheng, 2.3 Academic Literacy In PISA 2018, 15-year-old student academic literacy in math, reading and science are measured and recorded. Specifically, “mathematical literacy” in PISA 2018 refers to an individual’s capacity to “formulate, employ, and interpret math in a variety of contexts” (OECD, 2019a). It includes “reasoning mathematically, and using mathematical concepts, procedures, facts, and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena” (ibid). It assists individuals to recognize the role that math plays in the world and to make the well-founded judgements and decisions needed by constructive, engaged, and reflective citizens. Reading literacy in PISA 2018 refers to the ability to “understand and use those written language forms required by society and/or valued by the individual” (ibid). Readers can construct meaning from texts in a variety of forms. They read to learn, to participate in communities of readers in school and everyday life, and for enjoyment. Scientific literacy in PISA 2018 assesses students’ content, procedural and epistemic knowledge, as well as scientific competencies to “explain phenomena scientifically, evaluate and design scientific inquiry, interpret data and evidence scientifically” (ibid). The results for mathematical, reading, and scientific literacy are presented in Figs. 3, 4 and 5 respectively. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Mathematical literacy. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Reading literacy. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Scientific literacy. As seen in figures above, Chinese students consistently rank first among the countries in all of the three subjects. Moreover, it seems that students in Asian countries (i.e., ROK, Japan) perform better than their counterparts in the Western countries (i.e., the U.S., Germany, France, the U.K., the Netherlands). In PISA 2018, students are asked to report the extent to which they agree with the following statements: “When I am failing, I worry about what others think of me”; “When I am failing, I am afraid that I might not have enough talent”; and “When I am failing, this makes me doubt my plans for the future”. These statements are combined to create the index of fear of failure. Positive values in this index mean that the student expresses a greater fear of failure than did the average student across the OECD countries. Negative values in this index mean that the student expresses a lower level of fear of failure than the average student across the OECD countries. The results are presented in Fig. 6. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Fear of failure. As seen in Fig. 6, the fear of failure of Chinese students is at a medium level compared with that of students in other countries. Students from Japan, the U.K., ROK, and the U.S. tend to have higher levels of fear of failure, while students in Germany and the Netherlands tend to have lower levels of fear of failure. The results might occur due to a variety of reasons such as student past success or failure experiences and how school teachers guide students to face failures. Perceived meaning in life reflects student attitudes toward life. In PISA 2018, students are asked to report the extent to which they agree with the following statements: “My life has clear meaning or purpose”; “I have discovered a satisfactory meaning in life”; and “I have a clear sense of what gives meaning to my life”. These statements are combined to form the index of meaning in life. Positive values in the index indicate greater meaning in life than the average student across the OECD countries. Negative values in this index indicate lower meaning in life than the average student across the OECD countries. The results are presented in Fig. 7. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Eudaemonia: Meaning in life. As seen in Fig. 7, the level of Chinese students’ perceived meaning in life is similar with that of students in the U.S., Germany, France, and ROK. However, students in the U.K., Japan and the Netherlands tend to have lower levels of perceived meaning in life. Professional development refers to the various activities (i.e., courses/workshops, education conferences, qualification program, observation visits to other schools, mentoring) that can help develop an individual’s knowledge and skills, as well as other characteristics as a teacher. In TALIS 2018, teachers from different regions or countries are asked to evaluate how effective they perceive the professional development they have participated in. The results are presented in Fig. 8. Source Adapted from OECD (2019c). Notes Germany data are not available Professional development. As seen in Fig. 8, the scores of perceived effective professional development ranges from 9.84 points to 14.05 points across the countries. Teachers in China tend to report a relatively lower level of effective professional development (=11.95 points) compared to those from the U.S., France, ROK, and the Netherlands, while it is higher than those from the U.K. and Japan. TALIS 2018 elicits teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs by asking them to assess their ability to perform well in a range of tasks related to classroom management, instruction, and students’ engagement. The results are presented in Fig. 9. Source Adapted from OECD (2019c). Notes Germany data are not available Teacher self-efficacy. As seen in Fig. 9, the data of teacher self-efficacy are at similar levels across the countries, ranging from 12.62 points to 12.83 points. In particular, teachers from the U.S. tend to have the highest level of self-efficacy, followed by ROK, China, France, the U.K., Japan, and teachers from the Netherlands tend to report the lowest self-efficacy. In TALIS 2018, teachers from different regions or countries are asked to report the extent to which they have experienced stress at work. This may reflect education pressure from the perspective of teachers. The results are presented in Fig. 10. Source Adapted from OECD (2019c). Notes Germany data are not available Teacher workload stress. As seen in Fig. 10, teachers in Shanghai of China report lower levels of workload stress than that of teachers in other countries except for France. Teachers in ROK report the highest level of workload stress, followed by the Netherlands, the U.K. (England), Japan, the U.S., China (Shanghai), and then France. In general, it seems that the workload stress of teachers in the Asian countries (i.e., ROK, Japan) is higher than that of teachers from the Western countries (i.e., France, the U.S.). PISA 2018 measures school resources by asking school principals’ perceptions of potential factors hindering instruction at school (“Is your school’s capacity to provide instruction hindered by any of the following issues?”). An index of shortage of educational staff is derived from the following indicators: “a lack of educational material”, “inadequate or poorly quality educational material”, “a lack of physical infrastructure”, “inadequate or poorly quality physical infrastructure” (OECD, 2019a). Positive values in this index mean that principals view the amount and/or quality of educational material in their schools as an obstacle to providing instruction to a greater extent than the average across the OECD countries. Negative values in this index mean that principals view the amount and/or quality of educational material in their schools as an obstacle to providing instruction to a lesser extent than the average across the OECD countries. The results are presented in Fig. 11. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Shortage of educational materials. As seen in Fig. 11, principals in China report a lower level of shortage of educational materials than the average of OECD countries (<0). Also, the value tends to be lower than that of Japan, ROK, Germany, the U.K., and France, while higher than that of the U.S. and the Netherlands. Similar to shortage of educational material, PISA 2018 also measures shortage of school resources. An index of shortage of educational staff was derived from following four indicators: “a lack of teaching staff”, “inadequate or poorly qualified teaching staff”, “a lack of assisting staff”, and “inadequate or poorly qualified assisting staff” (OECD, 2019a). Positive values in this index mean that principals view the amount and/or quality of the human resources in their schools as an obstacle to providing instruction to a greater extent than the average across the OECD countries. Negative values in this index mean that principals view the amount and/or quality of the human resources in their schools as an obstacle to providing instruction to a lesser extent than the average across the OECD countries. The results are presented in Fig. 12. Source Adapted from OECD (2019a) Shortage of educational staff. As seen in Fig. 12, principals in China report a higher level of shortage of educational staff than the average of OECD countries (<0). Also, the value tends to be lower than that of Japan, while higher than that of the U.S., Germany, France, the U.K., ROK, and the Netherlands.

2.4 Fear of Failure

2.5 Eudaemonia: Meaning in Life

2.6 Professional Development

2.7 Teacher Self-efficacy

2.8 Teacher Workload Stress

2.9 Shortage of Educational Materials

2.10 Shortage of Educational Staff

3 Excellence Indicators

3.1 Design

When it comes to education, excellence is on top of the agenda. Yet, the meaning attributed to the notion of excellence differs remarkably among educators, researchers, and policymakers. This section attempts to propose representative indicators that can comprehensively reflect the excellence levels of junior secondary education for China in a global context.

In addition to China, a total of seven developed countries are selected in this section for comparison purposes, i.e., the U.S., the U.K., France, Germany, the Netherlands, Japan, and ROK. The objective of this section is to allow for a global view of the junior secondary education systems, and to help countries review current education conditions and thus develop informed educational policies.

While selecting the excellence indicators, two general principles or rules are followed, that is, the indicators need to be internationally comparable and provide comprehensive coverage. The indicators should make sense for China and for the world. Moreover, specific data associated with the indicators should also be available for most of the countries. Also, the proposed indicators should comprehensively reflect the excellence levels from different perspectives (i.e., education input, education output) and from different stakeholders (i.e., teachers, students).

Following the above two principles or rules, a total of nine excellence indicators are analyzed in this section, including:

-

Total expenditure on junior secondary education per full-time equivalent student

-

Student–teacher ratio

-

Proportion of teachers fully certified by the appropriate authority

-

Student repetition rate

-

Student scientific literacy

-

Student reading literacy

-

Student mathematical literacy

-

Student sense of belonging to school

-

Teacher job satisfaction.

3.2 Definitions and Sources

A total of nine indicators are selected to reflect the excellence level of junior secondary education for China and for the world. Data sources of these excellence indicators are presented in Table 1, and definitions for each of the indicators are also defined below. As seen, OECD has been the primary data source with gaps filled in with other sources (i.e., UNESCO, China Statistical Yearbook).

3.2.1 Total Expenditure on Junior Secondary Education Per Full-Time Equivalent Student

This indicator reflects national education input for junior secondary schools, which is calculated by dividing the government total expenditure on junior secondary education by the corresponding full-time equivalent enrollment. Expenditure in national currency is converted into equivalent U.S. dollars (US$) by dividing the national currency figure by the purchasing power parity (PPP) index for GDP. The PPP conversion factor is used because the market exchange rate is affected by many factors (interest rates, trade policies, expectations of economic growth, etc.) that have little to do with current relative domestic purchasing power in different countries. Data for China are retrieved from China Statistical Yearbook 2020, and for other countries from OECD-sponsored Education at a Glance 2019.

3.2.2 Student–Teacher Ratio

This indicator reflects education input for junior secondary schools, which refers to the ratio of students to teaching staff. Data for both China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored Education at a Glance 2019.

3.2.3 Proportion of Teachers Fully Certified by the Appropriate Authority

This indicator reflects education input for junior secondary schools, which refers to the ratio of teachers who have the required credentials to teach in junior secondary schools. Data for both China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored PISA 2018.

3.2.4 Student Repetition Rate

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of students, which refers to the proportion of students from a cohort enrolled in a given grade at a given school year who study in the same grade in the following school year. Ideally repetition rate should approach 0%. High repetition rate reveals problems in the internal efficiency of the education system and possibly reflect a poor level of instruction. Data for China and for other countries are retrieved from UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (2015).

3.2.5 Student Scientific Literacy

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of students. Data for both China and other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored PISA 2018. In PISA 2018, scientific literacy refers to students’ ability to “explain phenomena scientifically, evaluate and design scientific inquiry, interpret data and evidence scientifically” (OECD, 2019a).

3.2.6 Student Reading Literacy

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of students. Data for China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored PISA 2018. In PISA 2018, reading literacy refers to students’ ability to “understand and use those written language forms required by society and/or valued by the individual” (OECD, 2019a). Readers can construct meaning from texts in a variety of forms. They read to learn, to participate in communities of readers in school and everyday life, and for enjoyment.

3.2.7 Student Mathematical Literacy

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of students. Data for China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored PISA 2018. In PISA 2018, mathematical literacy refers to students’ ability to “formulate, employ and interpret math in a variety of contexts” (OECD, 2019a). It includes “reasoning mathematically and using mathematical concepts, procedures, facts, and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena” (OECD, 2019a). It assists individuals to recognize the role that math plays in the world and to make the well-founded judgements and decisions needed by constructive, engaged, and reflective citizens.

3.2.8 Student Sense of Belonging to School

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of students, which refers to students’ feelings of being accepted and valued by their peers and by others at school. Data for both China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored PISA 2018.

3.2.9 Teachers’ Job Satisfaction

This indicator reflects education output from the perspective of teachers, which refers to teachers’ overall evaluation of being a teacher at a school, such as the sense of fulfilment and gratification that they get from the work. Data for China and for other countries are retrieved from OECD-sponsored TALIS 2018.

3.3 Findings

3.3.1 Raw Data Results

The raw means of the nine excellence indicators for the eight countries are presented in Table 2.

As seen in Table 2, the total expenditure on junior secondary education per full-time equivalent student ranges from US$3,942 to US$14,249 across the eight countries. Obviously, the total expenditure per student in China is much lower than that of developed countries. Student–teacher ratio ranges from 12.59 to 16.18 across the eight countries. China has the lowest student–teacher ratio compared with the developed countries. The lower student-to-teacher ratio may indicate more opportunities for one-on-one time with students so that their learning challenges can be identified early, and effective measures can be implemented quickly. Lower student-to-teacher ratio may also lead to better relationships between teachers and students, and lower behavior problems and disruptions. Teachers of smaller classrooms spend less time on discipline and classroom management. This leaves more time for building a meaningful relationship with each student, as well as actual teaching. The proportion of teachers certified by the appropriate authority ranges from 74.80 to 96.20% across the countries. In particular, China has the highest proportion of teachers certified by the appropriate authority. Student repetition rate for all the eight countries remains at a relatively low level (<5%). As for scientific, mathematical, and reading literacy, students from the Asian countries (i.e., Japan, ROK, China) tend to have better achievements than their western counterparts (i.e., the U.S., the U.K., Germany, France, the Netherlands). In particular, China ranks the top among all the selected countries. Students’ sense of belonging to school ranges from −0.24 to 0.28 across the countries. The mean score of China is −0.19 (<0), which is lower than the average score of the OECD countries. The level of teachers’ job satisfaction ranges from 81.80 points to 93.90 points across the countries. The job satisfaction of teachers in China remains at a relatively high level (index score was 90.50), as compared to those from other countries. In fact, job satisfaction plays an essential role in the overall commitment and productivity of the school organization. The more satisfied teachers are with their jobs, the better their participation and commitment to the school would be.

3.4 Transformed Data Results

As seen above, the unit and scale of the nine excellence indicators are different, and thus it may be hard to make international comparison among the countries as a whole. In order to facilitate comparison, the raw data have been transformed in this section using the following method: the country with the highest mean value in a specific variable would be assigned a score of 100, and the score allotted to other countries would be based on the raw score ratio between the specific country and the country with the highest value. For example, China was assigned a transformed score of 100 on mathematical literacy because its raw score was the highest (with a raw score of 591 points). The raw score of the U.S. was 478 points. The ratio between China and the U.S. was 1: 0.8088, and thus the transformed score for the U.S. was 80.88. The above data transformation method has been applied for eight out of the nine indicators in this section except for student repetition rate. The repetition rate for all of the eight countries is at a relatively low level (<5), thus all the countries were given a score of 100 on this indicator. The transformed data results are presented in Table 3.

3.5 Discussion

China has shown both strengths and weaknesses in junior secondary education when compared with developed countries. From the perspective of education input, the total expenditure on junior secondary education per equivalent full-time student in China is much lower than that of the other countries. This result seems to be reasonable because China is still a develo** country. However, China has the highest proportion of teachers fully certified by the appropriate authority, and student–teacher ratio was the lowest among the selected countries. This seems to reflect that China has put great emphasis on the qualification and professionalization of teachers to ensure education quality. From the perspective of education output, the repetition rate in China is low, and Chinese students tend to excel in scientific, mathematical, and reading literacy compared with other countries. However, some of student social-emotional development (i.e., sense of belonging to school) may still need to be improved. Moreover, teachers’ job satisfaction is at a relatively high level.

4 Best Practices

4.1 Promoting Well-Rounded Education (Suzhi Education) Through Assessment Reform

Assessment reform plays an important role in promoting a country’s education quality. In China, one of the most important assessments for junior secondary school students is the high school entrance examination, which is commonly held at the end of June each year by local education authorities. This entrance examination is very important because it determines whether students can enter a senior high school or not. Although most students pass the examination, they must gain high scores in order to be admitted into select high schools and thus receive better education. However, when students fail the examination, students can choose to attend a technical secondary school or vocational school to receive career training, and work as technicians in companies or factories afterwards.

In fact, policymakers, educators, and the public have been discussing reforming the high school entrance examination for a long time. One major concern with the exam is the outcomes-focused nature of the exam that may put students under tremendous pressure from a young age and may overshadow the goal of well-rounded education. To respond to the concern, Chinese government and educational institutions have attempted to deepen reforms of education assessment, proposing different initiatives to transitioning from traditional summative assessment to formative assessment with the purpose of promoting students’ holistic development.

For instance, Shanghai of China has proposed and adopted some alternative formative assessments in junior secondary schools. Two primary initiatives are school-based curriculum and Green Academic Evaluation System (Reyes & Tan, 2019).Footnote 1 Specifically, schools in Shanghai are given the autonomy to design and launch a series of courses, programs, and activities that meet the diverse needs and interests of students. Together with the new courses, programs, and activities under the school-based curriculum are alternative and formative assessment modes. Students are evaluated based on their daily performance of real-life tasks through experiments, oral presentations, poster displays, and research projects (Shen, 2007; Tan, 2013). Of special mention among the new alternative formative assessment method is the Integrated Quality Appraisal, which is aimed at well-rounded education. This appraisal is intended to evaluate students based on the following aspects: development of moral characters, cultivation of traditional Chinese culture, school courses taken and obtained academic results, innovative spirit and practical ability, physical and mental health and interests and talents (Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, 2014). To ensure reliability and validity, schools are required to objectively record students’ growth process and comprehensively reflect their well-rounded development (ibid). Unlike outcome-based exams, the Integrated Quality Appraisal is formative as it accumulates the daily and all-round growth and achievement of students throughout their learning years. Teachers are expected to track student learning and developmental progress through the Growth Record Booklet by taking note of student moral quality, citizenship quality, learning ability, social interaction and cooperation, and participation in sports, health, and aesthetics (Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, 2006). This appraisal enables students to identify and understand their own strengths and the areas of improvement under the guidance of teachers (Tan, 2013).

Another initiative taken by Shanghai in China to reform education assessment is the Green Academic Evaluation System. This system aims to change the prevailing exam-oriented mindset in Shanghai by focusing not only on student academic performance but also on their physical and mental health as well as moral conduct (Reyes & Tan, 2019). The Green Indices (1.0) included a total of 10 indicators, which were first carried out in 2011 for a total sample size of 63,640 students at the fourth and nineth grades, as well as 9,445 teachers and 804 principals across Shanghai (ibid). Later, the indicators were revised in 2018 (Green Indices 2.0), and the revised 10 indicators are as follows:

-

Student academic performance index, such as the degree of students meeting the academic standard, student higher-order thinking skills and art literacy

-

Student physical and mental health index

-

Student moral conduct and social behavior index, such as prosocial behavior, national identity, international perspectives

-

Student learning motivation index, such as learning self-confidence

-

Student school identity index, such as teacher-student relationship, peer relationship, and sense of school belonging

-

Student schoolwork burden and academic pressure index

-

Teachers’ curriculum leadership index, such as teacher teaching theory, teaching methods and assessment capability

-

Principals’ curriculum leadership index, such as curriculum plan, curriculum execution and curriculum assessment capability

-

Education equity index

-

Improvement index.

4.2 Promoting High-Quality and Well-Balanced Education Through Teacher Rotation Program

The imbalanced development of education between urban and rural areas has been perplexing China for a long time. To bridge the current imbalance in education resources between urban and rural schools, MOE along with seven other ministries and governmental departments in China released new guidelines (MOE et al., 2022) in April of 2022, in which more experienced and talented teachers and principals are encouraged to teach students at rural schools. According to the new document, teachers seeking promotion are required to teach at rural or less-developed schools for more than a year, and those who have more than three years of teaching experience at such schools will be preferred in becoming principals. The purpose of the policy is to bring high-quality education resources to more schools in the city. Districts with poor teaching resources can receive better support via methods such as dual-teacher classes during the program. The new policy provides incentives for qualified educators to move, such as higher pay and rotation participation being taken into account when promotion is considered.

Bei**g is among the first batches of cities in China to enact this guideline. More specifically, primary and junior secondary school teachers in Bei**g’s public school system who have worked at the same school for more than six years will be asked to shift to a new school in another district and share their knowledge and experiences with new colleagues and students. Educators who are more than five years away from retirement and have worked at the same school for over six years are qualified for the program. Teachers who have already changed schools identified that the program presents both challenges and opportunities. Li Bao**, an English language teacher at Bei**g Huiwen Middle School in Dongcheng district, said “Students from different schools show different characteristics”(Du, 2021). Li transferred to a school in Chaoyang district in September of 2021. “In the process of handling the changes, my abilities in teaching and communication have improved”, she said (ibid). Lin Ming, the director of Hongshan Branch of Bei**g Huiwen Middle School, said that making the participation of the rotation program part of promotion assessments provided a platform for young and middle-aged teachers to develop. Yuan ** him cover basic living expenses. With the great help of Zhang, the student resumed school, and successfully graduated from the middle school after three years of hard work. Another example is that Zhang became a father in 2001. Unfortunately, due to brain hypoxia, his son needed special care in an incubator in the hospital. During that time, Zhang needed to travel almost every day between different counties or towns to get medicine for his son. However, the family emergency did not prevent him from working hard at the school. He persisted to teach math for the nineth grade students, and never asked for leave or even delayed lessons. Moreover, he made use of after-class time to help students improve without asking for any compensation. At the end of the semester, the academic excellence rate of his class ranked in the top third in the county, and the overall performance of the students was even better than those from the middle schools in the town.

Zhang has also been a keynote speaker at many forums on educational ethics and pedagogy, actively sharing effective teaching practices for schools in rural areas. For example, he suggested to keep a notebook to write down all the wrong answers students give in mathematical exams and exercises which turned out to be effective in improving student math performance. This method has now received wide recognition from experts in the field of education and has now been promoted in the entire school. Moreover, he also explored and proposed a new teaching mode specifically suitable for rural students, and gradually formulated his own teaching style. These valuable experiences have been summarized and published in the book Practice – Seeking Teachers’ Professional Happiness and Excellent Teacher Growth Cases and Class Documentation.

5.2 Feng Enhong: Brave Education Innovator

Feng Enhong is the founder and principal of Shanghai Jian** High School (** High School, such as math Olympic competition, driving, weaving, photographing, computer multimedia technology, calligraphy, sculpture, and chess. In addition, various extracurricular activities have also been organized to develop students’ interests. For example, one of the grandest school activities is the Art Festival. At the festival, students can make full use of creativity and initiative to design interesting activities, such as hot-air balloon, culinary experiences, as well as music and dance performances.

As for the idea of “Standard plus Choice”, it means that there should be clear and detailed regulations or rules to manage the school, which cover the responsibilities of the principal even to school sanitary work. Meanwhile, the school should provide diversified choices such as in course selection and in many other areas. For example, Shanghai Jian** High School has set up many school-based courses in addition to the national required courses, and various student clubs have been organized to enrich student school life. The successful experience of Shanghai Jian** High School has subsequently been propagated to the whole country, and relevant school management material has been translated to English and produced international impacts as a result. In 2003, a television drama called “It is Rich in Golden Apple” has been broadcasted in China, which has taken Feng as a prototype and depicts the story of education reform in China.

6 Latest Research

In this section, latest research in the field of junior secondary education is summarized. The purpose of this section is to present the current research focuses of Chinese junior secondary education.

6.1 An Overview of Research on Junior Secondary Education in China

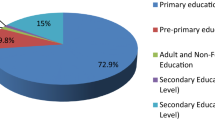

Using “junior secondary education” as the keyword, the latest 10-year Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) journal papers (2012–2022) are searched in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) website. The distribution of the most studied topics related to junior secondary education is presented in Fig. 13.

As seen in Fig. 13, the most studied topic related to junior secondary education is compulsory education (with 102 CSSCI journal papers from 2012 to 2022), followed by topics featured by evidence-based research (with 61 journal papers), primary and middle schools (with 42 journal papers), math learning (with 37 journal papers), comparative study (with 36 journal papers), junior secondary education students (with 29 journal papers), core competencies (with 27 journal papers), teachers in primary and middle schools (with 21 journal papers), English language learning (with 18 journal papers), physics learning (with 16 journal papers), Chinese language arts learning (with 13 journal papers), balanced development (with 13 journal papers), migrant students (with 12 journal papers), education equity (with 12 journal papers) and math textbooks (with 10 journal papers).

From the distribution of the topics, evidence-based research is receiving increasing attention in the field of Chinese language arts education over the past decade. In addition, these topics can roughly be summarized into three broad categories: school subject teaching and learning (i.e., math learning, English language learning, physics learning, and Chinese language arts learning); balanced development of junior secondary education (i.e., education equity, migrant children); and student core competencies. Additional information about each of these categories/areas is provided below.

6.2 Research on School Subject Teaching and Learning

One of the most studied topics around junior secondary education of China is school subject teaching and learning, which deals with topics related to exploring general rules and efficient ways for educators to impart subject-related knowledge for students to better understand subject matter and foster core competencies, as well as for designing and analyzing textbooks and curriculum standards (i.e., Zhang & Hu, 2022; Gu & Zhang, 2021; Wang, 2020).

For instance, Lin et al. (2021) conducted an experimental study to explore the effect of mind map** on junior secondary school students’ Chinese language arts learning and creative thinking. Results indicate that four-month mind map (i.e., diagrams to help visualize thoughts and communicate them to others) training could significantly improve student Chinese language arts learning interest and creative thinking skills. Wu and Zhang (2019) examined the effect of math writing (i.e., writing down the understanding of math concepts, and recording the problem-solving processes) on math performance among Chinese minority middle school students. Results suggest that math writing could significantly improve student math performance, as well as their math learning motivation. Wang (2020) found that collectivism in textbooks has undergone dramatic changes since the reform and opening-up in China by analyzing the protagonists in Chinese language arts textbooks, and there exists a complex relationship between collectivism and the individualization of the society. To fully optimize textbooks, education should pay more attention to the value of collectivism in resolving inherent dilemma of individualized society and reconstruct collectivism in textbooks.

6.3 Research on Balanced Development of Junior Secondary Education

Recent years have witnessed an increasing number of journal papers focusing on the balanced development of junior secondary education, including such topics as comparing educational resources between rural and urban areas, as well as employing technology to narrow down the gap between different areas.

For instance, Liu (2021) identified some potential issues or problems of student evaluation of comprehensive practical activities in primary and junior secondary schools. They suggested that educators should pay more attention to selective evaluation rather than promoting evaluation, to unified evaluation rather than individualized evaluation, to teacher evaluation rather than diversified evaluation, to quantitative evaluation rather than qualitative evaluation, to routine work rather than normal evaluation. Feng et al. (2022) proposed the idea of assessing student comprehensive skills using big data analytical techniques. Specifically, they suggested that the comprehensive quality assessment should evaluate student from diverse aspects such as physical health, mental health, moral characteristics, scientific literacy and humanity literacy. In order to achieve accurate assessment, educators should collect relevant data from teachers, peers, parents and students themselves, and establish individual development profile for each student. This profile would record student learning progress and growth, and help teachers design and implement more adaptive and individualized instruction.

7 National Policies

In this section, some basic and recent national policies about junior secondary education in China are introduced, with the purpose of providing detailed information about junior secondary education in China from the policy perspective. It is worth noting that these policies are stated and organized into themes in this section, in order to promote a better understanding of the policies.

7.1 Policy Development on Junior Secondary Education in China

One major goal of junior secondary education is to nurture children so that they will become adults with well-rounded abilities, not just people who can achieve high test scores. In order to promote holistic development, Chinese government has issued a series of relevant guidelines or policies over the past 30 years. These policies are primarily focused on two important aspects: fostering student core competencies that help them be better prepared for the future world; and relieving student academic burden to make room for their well-rounded development. Below some basic education policies around these two aspects are summarized.

7.1.1 Fostering Student Core Competencies

In 1999, the Third National Education Work Conference themed “Deepen Educational Reform, Promote Well-Rounded Development” was held in Bei**g. At the same year, Decisions on Deepening Educational Reform and Promoting Well-Rounded Education was issued (The State Council, 1999), stipulating the goal and the essence of China’s well-rounded education, as well as the specific measures that could be taken to guarantee the implementation of the policy, which marked the beginning of China’s well-rounded education.

In 2006, the Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China was amended, in which well-rounded education was first highlighted at the country’s level (National People’s Congress, 2006). According to the law, the national policy on education shall be implemented and well-rounded education shall be carried out in compulsory education to improve the quality of education and enable children and adolescents to achieve well-rounded development—morally, intellectually, and physically—so as to lay the foundation for cultivating well-educated and self-disciplined builders of socialism with high ideals and moral integrity. In addition, the educational and teaching work shall be in line with the education rules and the characteristics of the physical and mental development of students, be geared to all students, impart knowledge and enlighten people, integrate moral education, intellectual education, physical education and aesthetic education in the educational and teaching activities. Moreover, it should focus on the cultivation of the students’ independent thinking skills, creativity, and practical skills so as to promote the well-rounded development of students.

In 2010, the Outline of the National Plan for Medium- and Long-term Education Reform and Development (2010–2020) (The State Council, 2010) was issued, further stipulating that education shall promote student well-rounded development. The Outline specified that moral education, intellectual education, physical education, and aesthetic education shall be stepped up and improved in an all-round way. It is imperative to give equal footings to cultural learning and moral edification, to theoretical study and social practice, and to well-rounded education and individual characteristics. Great importance should be attached to physical health. Students’ physical education courses and time for extracurricular activities must be guaranteed and the quality of physical education must be improved. In the meantime, fine education in mental health shall be provided to improve students’ mental and physical health. Education in aesthetics shall be intensified to instill a cultured aesthetical taste and enhance their cultural attainment. Labor education should be strengthened to cultivate their love for work and the working people.

In 2016, MOE put forward the concept of student core competencies. At the same year, the Core Competencies and Values for Chinese Students’ Development (People’s Daily, 2019) was released, which was an iconic event in the well-rounded education field. Policies attach more importance to students’ comprehensive competencies instead of test scores, and MOE proposed that tests of students’ aesthetic abilities will be added to the senior high school exams in 2022.

In June of 2019, the Guidelines on Deepening the Reform of Education and Teaching and Comprehensively Improving the Quality of Compulsory Education was issued. The Guidelines aim to develop an education system that foster citizens with an all-round moral, intellectual, physical, and aesthetic grounding, in addition to a hard-working spirit, according to the document. The key points of the Guidelines include:

-

According to the Guidelines, compulsory education should emphasize the effectiveness of moral education with emphasis on cultivating ideals and faith, core socialist values, China’s excellent traditional culture, ecological civilization, and mental health.

-

The Guidelines stresses elevating intellectual grounding level to develop the cognitive ability and the sense of innovation of the students.

-

The Guidelines also calls for strengthening physical education, enhancing aesthetic training with more art curriculums and activities, and encouraging students to participate in more physical work to boost their hard-working spirit (The State Council, 2019).

7.2 Relieving Students’ Academic Burden

Compared to other countries, the academic pressure of Chinese students is relatively intense. According to statistics, the market share for private tutoring in China exceeded eighty million in 2020, and over 13.70 million elementary and middle school students attended private tutoring activities (Sina, 2020). In order to reduce student academic workload, the government released the Guidelines on Further Easing the Burdens of Excessive Homework and Off-Campus Tutoring for Students Undergoing Compulsory Education (the “Double Reduction” policy) on July 24, 2021 (The State Council, 2021). The Guidelines took immediate effect on the day of its release.

“Double Reduction” in the Guidelines refers to a reduction in the total amount and time of commitment required by school homework and a reduction in the burden of off-campus or after-school training programs. Based on the Guidelines, the “Double Reduction” policy is intended to improve the overall quality of school education, reduce excessive study burdens, and protect the health of students, relieve the burdens and anxiety of parents, reduce social inequity, further regulate and standardize off-campus training (including both online and off-line training), and strictly implement the Compulsory Education Law, the Protection of Minors Law and other laws and regulations governing the education industry.

While the Guidelines set out various goals and requirements for in-school education, particular emphasis is placed on regulating after-school private tutoring activities. Some key points in the document include (Ross et al., 2021):

-

New subject-based off-campus and after-school training institutions targeting compulsory education students will not be approved by local authorities.

-

All existing subject-based off-campus training institutions will be required to convert to or register as “non-profit organizations”.

-

All online subject-based training institutions will be required to obtain approval from the local government.

-

For non-subject-based training institutions (i.e., sports, art, music programs), local governments should clarify the corresponding departments in-charge, formulate standards by subject area, and implement a strict review and approval regime.

-

All subject-based training institutions are prohibited from conducting Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) or otherwise raising funds from capital markets.

-

Public companies are prohibited from investing in any subject-based training institutions through stock market financial transactions or acquisitions of assets from such institutions in the form of equity or cash.

-

Foreign capital is prohibited from engaging in mergers or acquisitions, trustee arrangements, franchising, or using “Variable Interest Entity” (VIE) structures to control or participate in subject-based training institutions.

-

Content review—a filing and supervision system will be established to control and monitor training materials and training content.

-

Excessive training and early education are prohibited. Non-subject-based training institutions are prohibited from engaging in subject-based training or providing overseas education courses.

-

Off-campus training institutions are prohibited from using national holidays, weekends or winter or summer breaks to organize subject-based training programs.

-

Training institutions are prohibited from enticing teachers away from public schools through improper means. Advertisements for training institutions are banned on mainstream media platforms.

-

Financing activities and capital injections into training institutions will be further regulated.

-

Some more developed cities such as Bei**g, Shanghai and Guangzhou will launch pilot programs to re-examine existing “subject-based” training institutions; offer in-school extracurricular programs by using school resources or inviting off-campus training institutions through a government-led selection process; and strengthen the regulation of training fees/charges.

The “Double Reduction” policy will bring a fundamental change to the landscape of China’s compulsory education, which aims to address the most prominent problems in compulsory education, that is, the excessive academic burden on primary and middle school students, and the off campus tutoring that overloads parents financially and mentally, and seriously hedged the outcomes of education reform. MOE and local education authorities in different localities are in the process of formulating detailed rules to implement the “Double Reduction” policy.

In addition to the “Double Reduction” policy, Chinese government has also issued a set of additional guidelines to ease student excessive workload. For example, on August 30, 2021, MOE issued a notice criticizing the high frequency and difficulty of exams and emphasis placed on test results, which harms the body and minds of students (MOE, 2021d). The amount of testing and homework has since been reduced in primary and middle schools, while measures have been taken to prevent test scores from being published and ranked. After-school services in public schools are being extended to support working parents, non-curriculum training sectors such as in the arts and sports are expanding, and new commitments to increase teachers’ salaries in public schools have been made.

Moreover, Chinese lawmakers have adopted a new law on family education promotion at a session of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee on October 23 of 2021. The Family Education Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China (National People’s Congress, 2021) stipulates that parents or other guardian of the minors shall be responsible for family education, while the state, schools and society provide guidance, support, and services for family education. In response to the country’s drive to relieve academic workload of young students, the law requires local governments at or above the country level to take effective measures to reduce the burden of excessive homework and off-campus tutoring in compulsory education. The law bans parents from placing an excessive academic burden on their children, stating guardians of the minors should appropriately organize children’s time for study, rest, recreation, and physical exercise. Parents are also required to play their part in preventing their children from being addicted to the internet. Pinning high hopes on their children, many Chinese parents would bend over backward to help their kids succeed. They are willing to fork out RMB200 (about US$31) or more for a 45 min tutoring class to help children score high in tests(**nhua, 2021b). Weighed down by workload, Chinese students are facing increasing incidence of myopia, more sleep deprivation and poor fitness that worry many.

7.3 Current Policy Highlights

Like many other countries, China has been grappling with providing equal educational resources to all students in recent years. Due to the long-standing urban–rural divide, schools in rural areas of China have significantly lagged their urban counterparts in many aspects, such as in school conditions, teaching workforce, and student academic performance. The Chinese central government has thus enacted a series of national and regional policies to deal with the urban–rural disparities. The policy on teacher rotation program is a recent example of such policy endeavors.

The teacher rotation program was initially proposed and implemented in large business corporates with the purpose of encouraging employers to step out of their comfort zones and to acquire new knowledge and skills from others. In the field of education, the rotation program was first introduced for teachers by Chinese government in 1996 as a way to promote the balanced development of compulsory education, and it was officially written in the amended Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China in 2006. Later, many different counties or districts in China began to pilot the teacher rotation program. For example, the total number of teachers participated in the rotation program in Wuhan province has reached 150,000 in 2020 since its first implementation in 2015 (Sina, 2021).

In August of 2014, MOE, together with other ministries jointly issued The Guidelines on Promoting Teacher Rotation in Compulsory Education Schools(Zhao, 2014). According to the Guidelines, no less than 10% of teachers in urban and high-quality schools should be rotated to teach in rural and poor schools each year. To prevent schools from sending less qualified teachers to rural schools, the policy requires at least 20% of the rotated teachers to be high-quality teachers. The policy also requires principals and deputy principals to be rotated to a different school after two terms of service in the same school. Teachers from rural schools and poor schools will have the opportunity to fill the vacated positions in urban schools and better-quality schools.

In fact, there are very few details about how the teacher rotation program should be executed in the national policy documents, leaving the autonomy to local governments at various levels. As seen from the current local government policies, the duration of the rotation program is typically two to three years for teachers and one term (typically three to six years) of service for principals. Teachers and school leaders would return to their original school afterwards. In some cases, teachers may be transferred to another school. The rotation is among schools within the same administrative district or county. There are a variety of enticements and requirements to encourage participation, such as cash bonuses, priority and or prerequisite for promotion, and housing privileges.

In response to the teacher rotation policy, the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission issued the Guidelines of Strengthening the Construction of Teachers’ Personnel Management System in January of 2021, in which the teacher rotation program has been added to the agenda. In August of 2021, the Bei**g Municipal Education Committee also declared to promote the teacher rotation program on a large scale and released the detailed implementation specifications.

8 Summary

This chapter provides an overview of the junior secondary education (middle school) of China. Over the past decades, Chinese government has issued a series of national and/or regional policies to meet current and anticipated future needs and challenges as the world is becoming more globalized and diverse, and great achievements have been made in improving the quality of the junior secondary education, particularly in eliminating illiterates, decreasing drop-out rates, and strengthening education equity. Moreover, a number of good education practices and inspiring stories emerged, which have become the most valuable assets in the development of China’s education cause.

From an international comparison perspective, results from international large-scale assessment indicate that Chinese students tend to excel in academic literacy (i.e., math, reading, science), and the qualification of teachers in junior secondary schools are also at a satisfactory level. However, the academic burden (i.e., total learning time per week) of Chinese junior secondary school students are still heavy, and there is still room to promote the development of student noncognitive skills.

However, it should be noted that the results in this chapter, particularly for the Highlighting Data section and the Excellence Indicators section, are primarily based on data retrieved from the international large-scale assessments such as PISA 2018 and TALIS 2018. The students/teachers in each country are only stratified samples selected from the whole country. Hence, the results’ generalizability is limited to certain extent. Moreover, some data (i.e., fear of failure, teacher self-efficacy) may suffer from self-report bias.

Notes

- 1.

Assessment reforms in high-performing education systems: Shanghai and Singapore.

References

Cheng, M. Y. (2010). **nzhongguo saomang yundong (The new China literacy campaign). Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.xhgmw.com/m/view.php?aid=8391

Chu, Z. H. (2019). The importance of compulsory education. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/global/2019-07/22/content_37493987.htm

Ding, Y. S. (2022). “Shuangjian” zhengce luodi 99% xiaoxue chuzhong tigong kehou fuwu (99 % of elementary and middle schools have provided after-school services since the implementation of the “Double Reduction” policy). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://guoqing.china.com.cn/2022-01/12/content_77984361.htm

Du, J. (2021). Bei**g’s teacher rotation policy aims to improve equity. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202108/26/WS6126cdefa310efa1bd66b254.html

Duan, X., Liu, C., & Qian, L. (2020). The effect of parents working outside on left-behind children’s basic education. World Economic Papers, 03, 107–120.

Feng, L., Wang, W., & Bian, C. Z. (2022). Jiyu rengong zhineng yu dashuju de xuesheng xiaoben zonghe suzhi **jia xinshengtai (The new era of student school-based comprehensive quality assessment based on artificial intelligence and big data). Zhongguo Dianhua Jiaoyu (China Educational Technology), 08, 118–121.

Gu, J. L., & Zhang, F. (2021). Chuzhong shuxue jiaokeshu zhong “jihe zhiguan” de sheji leixing ji yuanze (The design of “geometric intuition” in junior secondary school math textbooks: Types and principles). Shuxue Jiaoyu Xuebao (Journal of Math Education), 30(06), 59–63+91.

Lin, H., Wang, J., & Hu, Q. (2021). Chuzhong yuwen siwei daotu jiaoxue youshi de shizheng yanjiu (An empirical study of the advantages of mind map** in Chinese teaching). Jiaoyu Xueshu Yuekan (Education Research Monthly), 07, 92–97.

Liu, M. C., & Li, G. (2021). Zhongxiaoxue zonghe shijian huodong de xuesheng **jia: Wenti jianshi, yuanyin fenxi yu gai** celue (Student evaluation of comprehensive practical activities in primary and secondary schools: Problem inspection, cause analysis and improvement strategies). Zhongguo Kaoshi (Journal of China Examinations), (12), 46–55+74.

Liu, Y. Q. (2014). **nxi jishu dui yiwu jiaoyu quyu junheng fazhan yingxiang de yanjiu (Research on the impact of information technology on the balanced development of compulsory education in area of China). Zhongguo Dianhua Jiaoyu (China Educational Technology), 04, 37–43.

Ma, R. (2022). China launches integrated platforms for online education. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://www.classcentral.com/report/china-integrated-platforms/

Ma, Y. (2021). A cross-cultural study of student self-efficacy profiles and the associated predictors and outcomes using a multigroup latent profile analysis. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 71, 101071.

Ministry of Education. (2021a). Guanyu kaizhan xianyu yiwu jiaoyu youzhi junheng chuangjian gongzuo de tongzhi (Notice on promoting quality and balanced development of compulsory education at county level). Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3321/202112/t20211201_583812.html

Ministry of Education. (2021b). Educational statistics yearbook of China 2020. China Statistics Press.

Ministry of Education. (2021c) Shancheng xiangcun li wusi fengxian de “xiaogezi” jiaoshi (The devoted teacher in the rural village). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_zt/moe_357/2021/2021_zt18/jjsyr/202109/t20210906_559849.html

Ministry of Education. (2021d). Guanyu jiaqiang yiwu jiaoyu xuexiao kaoshi guanli de tongzhi (Notice on strengthening the management of examination in compulsory education schools). Retrieved September 9, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A06/s3321/202108/t20210830_555640.html

Ministry of Education. (2022). Yiwu jiaoyu laodong kecheng biaozhun (Course standard of labor education of compulsory education). Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A26/s8001/202204/W020220420582367012450.pdf

Ministry of Education, et al. (2022). Jiaoyubu deng babumen guanyu yinfa xinshidai jichu jiaoyu qiangshi jihua de tongzhi (Notice of Ministry of Education and seven governmental organizations on printing and distributing the plans on strengthening teaching forces for basic education). Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A10/s7034/202204/t20220413_616644.html

National Bureau of Statistics. (2021). China statistical yearbook 2020. China Statistics Press.

National People’s Congress. (1986). Zhonghua renmin gongheguo yiwu jiaoyu fa (Compulsory education law of the People’s Republic of China). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.anyonedy.com/edu/zheng_ce_gs_gui/jiao_yu_fa_lv/200603/t20060303_165119.shtml

National People’s Congress. (2006). Zhonghua renmin gongheguo yiwu jiaoyu fa (Compulsory education law of the People’s Republic of China). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2006-06/30/content_2602188.htm

National People’s Congress. (2021). Zhonghua renmin gongheguo jiating jiaoyu cu** fa (Family education promotion law of the People’s Republic of China). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_zcfg/zcfg_qtxgfl/202110/t20211025_574749.html

OECD. (2019a). PISA 2018 results (volume I): What students know and can do. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2019b). Education at a glance: Education finance indicators, OECD education statistics (database). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_FIN_RATIO&lang=en

OECD. (2019c). TALIS 2018 (database). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://www.oecd.org/education/talis/talis-2018-data.htm

People’s Daily. (2019). Zhongguo xuesheng hexin fazhan suyang (Core competencies and values for Chinese students’ development). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://edu.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0914/c1053-28714231.html

Reyes, V., & Tan, C. (2019). Assessment reforms in high-performing education systems: Shanghai and Singapore. In Khine, M.S. (ed.) International trends in educational assessment (pp. 25–39). Leiden: Brill/Sense.

Ross, L., Zhou, K., & Hale, W. (2021). China releases the “Double Reduction” policy in education sector. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/china-releases-double-reduction-policy-1019987/

Shanghai Municipal Education Commission. (2006). Shanghaishi jiaoyu weiyuanhui guanyu yinfa shanghaishi zhongxiaoxuesheng zonghe suzhi **jia fang’an (shixing) de tongzhi (Notice of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission on Shanghai’s elementary and secondary school students’ comprehensive appraisal plan). Retrieved August 4, 2022 from https://www.xiexiebang.com/a13/201905159/86ec35aff30ff0cf.html

Shanghai Municipal Education Commission. (2014). Shanghaishi shenhua gaodeng xuexiao kaoshi zhaosheng zonghe gaige shishi fang’an (Implementation plan to deepen the comprehensive reform for college entrance exam in Shanghai). Retrieved August 4, 2022 from https://xuewen.cnki.net/CJFD-SHJZ201428006.html

Shen, X. (2007). Shanghai educaion. Singpore: Thomson Learning

Sina. (2020). Kewai fudao shichang guimo da 8,000 yi yuan (The market share for private tutoring reached RMB800 billion). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://finance.sina.com.cn/chan**g/cyxw/2020-08-31/doc-iivhvpwy3987932.shtml

Sina. (2021). Wuhan: “Shuangjian” zhengce bei**gxia jiaoshi lungang zhidu jiang fahui gengda zuoyong (The teacher rotation program will make more influences under the “Double Reduction” policy). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://k.sina.com.cn/article_1784473157_6a5ce64502002adb7.html

Sohu. (2020). Feng Enhong: Haoke wufei jiu zhejiyang–sange weidu, sange yaosu, liangzhong tu**g (Feng Enhong: Three dimensions, three elements, and two approaches for a good class). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from https://www.sohu.com/a/559404191_121124212

Tan, C. (2013). Learning from Shanghai: Lessons on achieving educational success. Springer.

The State Council. (1999). Guanyu shenhua jiaoyu gaige quanmian tui** suzhi jiaoyu de jueding (Decisions on deepening educational reform and promoting well-rounded education). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.scio.gov.cn/wszt/wz/Document/930635/930635.htm

The State Council. (2010). Guojia zhongchangqi jiaoyu gaige he fazhan guihua gangyao (2010–2020 nian) (Outline of the national plan for medium- and long-term education reform and development [2010–2020]). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A01/s7048/201007/t20100729_171904.html

The State Council. (2019). Guanyu shenhua jiaoyu jiaoxue gaige quanmian tigao yiwu jiaoyu zhiliang de yijian (Guidelines on deepening the reform of education and teaching and comprehensively improving the quality of compulsory education). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2019-07/08/content_5407361.htm

The State Council. (2021). Guanyu **yibu jianqing yiwu jiaoyu jieduan xuesheng zuoye fudan he xiaowai peixun fudan de yijian (Guidelines on further easing the burdens of excessive homework and off-campus tutoring for students undergoing compulsory education). Retrieved July 24, 2022 from http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-07/24/content_5627132.htm

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2015). UNESCO institute for statistics database. Retrieved from July 28, 2022 from http://data.uis.unesco.org

Wang, M. (2020). Getihua shiyu xia jiaokeshu zhong jitizhuyiguan de bianqian fenxi: Yi chuzhong yuwen kewen zhujue renwu weili (Analysis of the changes of collectivism in textbooks from the perspective of individualization: Taking the protagonist in Chinese texts of junior secondary school as an example). Quanqiu Jiaoyu Zhanwang (Global Education), 49(07), 92–105.

Wu, H., & Zhang, K. (2019). An experimental study on the integration of mathematical writing into the math teaching of junior secondary school. Journal of Mathematics Education, 05, 51–58.

**aozhangwang. (2013). Zhuanfang Feng Enhong xiaozhang (Interview with Principle Feng Enhong). Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://www.xiaozhang.com.cn/fangtan/interview/10.html

**nhua. (2021a). China to promote quality, balanced compulsory education in county-level areas. Retrieved July 27, 2022 from https://english.www.gov.cn/statecouncil/ministries/202112/01/content_WS61a77365c6d0df57f98e5deb.html

**nhua. (2021b). China adopts new law on family education promotion. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/media_highlights/202110/t20211025_574765.html

Zhai, B., Liu, H. R., Li, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2012) Renlei jiaoyu shi shang de qiji: Laizi zhongguo puji jiunian yiwu jiaoyu he saochu qingzhuangnian wenmang de baogao (Miracle in the history of education: Report on China’s popularizing nine-year compulsory education and eliminating illiteracy among young and middle-aged people). Retrieved July 27, 2022 from http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xwfb/s5147/201209/t20120910_142013.html

Zhang, G. L. (2015). Jieshixue shijiaoxia wailai wugong renyuan suiqian zinv de xuexiao jiaoyu ronghe: Wenti yu duice (The equalization of migrant children’s school education based on the perspective of Hermeneutics: Problems and countermeasures). Jiaoyu Fazhan Yanjiu (Educational Development Research), 10, 53–38.

Zhang, H. R., Sheng, Y.Q., & Luo, M. (2019). Woguo yiwu jiaoyu junheng fazhan sishi nian: Huimou yu fansi–jiyu shuju fenxi de shijiao (Forty years of the balanced development of compulsory education in China: Retrospection and reflection–from the perspective of data analysis). **’nan Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) (Journal of Southwest University [Social Sciences Edition]), (01), 72–80+194.

Zhang, W. Z., & Hu, Z. H. (2022). Zhongmei chuzhong shuxue jiaokeshu chatu zhiliang de bijiao (A comparison of illustration quality of junior secondary school math textbooks in China and the United States). Shuxue Jiaoyu Xuebao (Journal of Math Education), 31(1), 64–69+84.

Zhao, Y. (2014). Teacher rotation: China’s new national campaign for equity. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://zhaolearning.com/2014/09/05/teacher-rotation-china’s-new-national-campaign-for-equity/

Zou, S. (2022). Students gain from digital learning. Retrieved July 28, 2022 from http://en.qstheory.cn/2022-04/07/c_736355.htm

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ma, Y. (2024). Secondary Education (Middle School) in China. In: Niancai, L., Zhuolin, F., Qi, W. (eds) Education in China and the World. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5861-0_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-5861-0_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-99-5860-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-99-5861-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)