Abstract

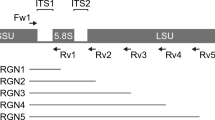

Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing have provided scientists with vastly enhanced tools to diagnose unknown tree diseases. One of these techniques is referred to as metabarcoding, which uses phylogenetically informative reference genes to taxonomically classify short DNA sequences amplified from environmental samples. Using metabarcoding, we are able to compare the microbiota of symptomatic and asymptomatic (including presumably naïve) samples and identify microbe(s) that are only present in symptomatic samples and could therefore be responsible for the undiagnosed disease. Metabarcoding involves two main steps: library preparation and bioinformatic processing. For library preparation, the appropriate reference gene for the organism of interest (i.e., bacteria, phytoplasma, fungi, or other eukaryotes, such as nematodes) is amplified from the DNA extracted from the environmental samples using PCR and prepared for sequencing. The bioinformatic processing includes four major steps: (1) quality check and cleanup on raw reads; (2) classification of the sequences into taxonomically informative groups (ASVs or OTUs); (3) taxonomy assignments based on the reference database; and (4) differential abundance and diversity analyses to identify microbes that are significantly associated with just symptomatic samples and that point toward the putative causal agent of the disease.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abdelfattah A, Malacrinò A, Wisniewski M et al (2018) Metabarcoding: a powerful tool to investigate microbial communities and shape future plant protection strategies. Biol Control 120:1–10

Roman-Reyna V, Dupas E, Cesbron S et al (2021) Metagenomic sequencing for rapid identification of Xylella fastidiosa from leaf samples. bioRxiv 6:e0059121

Deiner K, Bik HM, Elvira M et al (2017) Environmental DNA metabarcoding: transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Mol Ecol 26(21):5872–5895

O’Brien HE, Parrent JL, Jackson JA et al (2005) Fungal community analysis by large-scale sequencing of environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 71(9):5544–5550

Janda JM, Abbott SL (2007) 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: pluses, perils, and pitfalls. J Clin Microbiol 45(9):2761

Hadziavdic K, Lekang K, Lanzen A et al (2014) Characterization of the 18S rRNA gene for designing universal eukaryote specific primers. PLoS One 9(2):e87624

Prewitt ML, Diehl SV, Mcelroy TC et al (2008) Comparison of general fungal and basidiomycete-specific ITS primers for identification of wood decay fungi. For Prod J 58(4):66–71

Ewing CJ, Slot J, Benitez Ponce M-S et al (2021) The foliar microbiome suggests fungal and bacterial agents may be involved in the beech leaf disease pathosystem. Phytobiomes J. (in press)

Creer S, Deiner K, Frey S et al (2016) The ecologist’s field guide to sequence-based identification of biodiversity. Methods Ecol Evol 7(9):1008–1018

Nilsson RH, Anslan S, Bahram M et al (2019) Mycobiome diversity: high-throughput sequencing and identification of fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol 17(2):95–109

Pollock J, Glendinning L, Wisedchanwet T et al (2018) The madness of microbiome: attempting to find consensus “best practice” for 16S microbiome studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 84(7):e02627

Zinger L, Bonin A, Alsos IG et al (2019) DNA metabarcoding—need for robust experimental designs to draw sound ecological conclusions. Mol Ecol 28(8):1857–1862

Horton MW, Bodenhausen N, Beilsmith K et al (2015) Genome-wide association study of Arabidopsis thaliana’s leaf microbial community. Nat Commun 5:5320

Gundersen DE, Lee I-M (1996) Ultrasensitive detection of phytoplasmas by nested-PCR assays using two universal primer pairs. Phytopathol Mediterr 35(3):144–151

Gibb KS, Padovan AC, Mogen BD (1995) Studies on sweet potato little-leaf phytoplasma detected in sweet potato and other plant species growing in northern Australia. Phytopathology 85(2):169–174

Usyk M, Zolnik CP, Patel H et al (2017) Novel ITS1 fungal primers for characterization of the mycobiome. mSphere 2(6):e00488

Sapkota R, Nicolaisen M (2015) High-throughput sequencing of nematode communities from total soil DNA extractions. BioMed Cent Ecol 15:3

Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR et al (2019) Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol 37:852–857

R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S (2013) phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8(4):e61217

Paradis E, Schliep K (2018) Ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35:526–528

de Mendiburu F (2020) agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R package version 1.3-3

Foster Z, Sharpton T, Grünwald N (2017) Metacoder: an R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PLoS Comput Biol 13(2):1–15

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderation estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550

Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR et al (2010) Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26:1463–1464

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M et al (2020) vegan: Community ecology package. R package version 2.5-7

Lenth R (2021) emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.5.5-1

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B et al (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48

Beckers B, Op BM, De TS et al (2016) Performance of 16s rDNA primer pairs in the study of rhizosphere and endosphere bacterial microbiomes in metabarcoding studies. Front Microbiol 7:650

White TJ, Bruns T, Lee SB et al (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing for fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (eds) PCR protocols: a guide to methods and amplifications. Academic Press, Inc, San Diego, pp 315–322

Ramakodi MP (2021) Effect of amplicon sequencing depth in environmental microbiome research. Curr Microbiol 78(3):1026–1033

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Afaq M. Mohamed Niyas and Caterina Villari from University of Georgia for providing the modified 16S phytoplasma PCR protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature

About this protocol

Cite this protocol

Fearer, C.J., Malacrinò, A., Rosa, C., Bonello, P. (2022). Phytobiome Metabarcoding: A Tool to Help Identify Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Causal Agents of Undiagnosed Tree Diseases. In: Luchi, N. (eds) Plant Pathology. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 2536. Humana, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2517-0_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2517-0_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Humana, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-0716-2516-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-0716-2517-0

eBook Packages: Springer Protocols