Abstract

Background

Federal rules mandate that hospitals publish payer-specific negotiated prices for all services. Little is known about variation in payer-negotiated prices for surgical oncology services or their relationship to clinical outcomes. We assessed variation in payer-negotiated prices associated with surgical care for common cancers at National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated cancer centers and determined the effect of increasing payer-negotiated prices on the odds of morbidity and mortality.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional analysis of 63 NCI-designated cancer center websites was employed to assess variation in payer-negotiated prices. A retrospective cohort study of 15,013 Medicare beneficiaries undergoing surgery for colon, pancreas, or lung cancers at an NCI-designated cancer center between 2014 and 2018 was conducted to determine the relationship between payer-negotiated prices and clinical outcomes. The primary outcome was the effect of median payer-negotiated price on odds of a composite outcome of 30 days mortality and serious postoperative complications for each cancer cohort.

Results

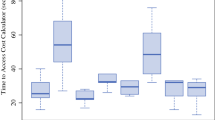

Within-center prices differed by up to 48.8-fold, and between-center prices differed by up to 675-fold after accounting for geographic variation in costs of providing care. Among the 15,013 patients discharged from 20 different NCI-designated cancer centers, the effect of normalized median payer-negotiated price on the composite outcome was clinically negligible, but statistically significantly positive for colon [aOR 1.0094 (95% CI 1.0051–1.0138)], lung [aOR 1.0145 (1.0083–1.0206)], and pancreas [aOR 1.0080 (1.0040–1.0120)] cancer cohorts.

Conclusions

Payer-negotiated prices are statistically significantly but not clinically meaningfully related to morbidity and mortality for the surgical treatment of common cancers. Higher payer-negotiated prices are likely due to factors other than clinical quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Poisal JA, Sisko AM, Cuckler GA, et al. National health expenditure projections, 2021–30: growth to moderate as COVID-19 impacts wane: study examines national health expenditure projections, 2021–30 and the impact of declining federal supplemental spending related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):474–86. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00113.

Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G, Levitt L. How much more than Medicare do private insurers pay? A review of the literature. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/. Accessed 16 July 2022

Sinaiko AD. What is the value of market-wide health care price transparency? JAMA. 2019;322(15):1449. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.11578.

Reinhardt UE. The disruptive innovation of price transparency in health care. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1927. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281854.

Glied S. Price transparency—promise and peril. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0316.

Medicare and Medicaid Programs. CY 2020 hospital outpatient PPS policy changes and payment rates and ambulatory surgical center payment system policy changes and payment rates. Fed Regist. 2019;84(229):65524–606.

**ao R, Ross JS, Gross CP, et al. Hospital-administered cancer therapy prices for patients with private health insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(6):603. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.1022.

**ao R, Rathi VK, Gross CP, Ross JS, Sethi RKV. Payer-negotiated prices in the diagnosis and management of thyroid cancer in 2021. JAMA. 2021;326(2):184. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.8535.

Wu SS, Rathi VK, Ross JS, Sethi RKV, **ao R. Payer-negotiated prices for telemedicine services. J Gen Intern Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07398-4.

Burkhart RJ, Hecht CJ, Acuña AJ, Kamath AF. Less than one-third of hospitals provide compliant price transparency information for total joint arthroplasty procedures. Clin Orthop. 2022;480(12):2316–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000002288.

Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1143–52. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263.

Farooq A, Merath K, Hyer JM, et al. Financial toxicity risk among adult patients undergoing cancer surgery in the United States: an analysis of the national inpatient sample. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(3):397–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25605.

Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and failure to rescue with high-risk surgery. Med Care. 2011;49(12):1076–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182329b97.

Childers CP, Guorgui J, Siddiqui S, Donahue T. Compliance of national cancer institute–designated cancer centers with January 2021 price transparency requirements. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(10):959. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3125.

Wang AA, **ao R, Sethi RKV, Rathi VK, Scangas GA. Private payer–negotiated prices for outpatient otolaryngologic surgery. Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211049330.

Wang AA, Rathi VK, **ao R, et al. Private payer-negotiated prices for FDA-approved biologic treatments for allergic diseases. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022;12(5):798–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22922.

Office of Inspector General. Medicare hospital prospective payment system: how DRG rates are calculated and updated. Office of inspector general 2001. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-00-00200.pdf. Accessed 16 July 2022

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. FY 2021 IPPS final rule home page. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/acute-inpatient-pps/fy-2021-ipps-final-rule-home-page. Accessed 16 July 2022

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. How to use the MPFS look-up tool. 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/How_to_MPFS_Booklet_ICN901344.pdf. Accessed 16 July 2022

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. PFS relative value files. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/PFS-Relative-Value-Files. Accessed 16 July 2022

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clinical laboratory fee schedule files. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files. Accessed 16 July 2022

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004.

Henderson M, Mouslim M. Assessing compliance with hospital price transparency over time. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(9):2218–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-08020-3.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. How to get the most out of hospital price transparency. 2021. https://www.cms.gov/hospital-price-transparency/consumers. Accessed 16 July 2022

Cooper Z, Doyle J, Graves J, Gruber J. Do higher-priced hospitals deliver higher-quality care? Natl Bur Econ Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3386/w29809.

Hussey PS, Wertheimer S, Mehrotra A. The association between health care quality and cost: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):27. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00006.

Jamalabadi S, Winter V, Schreyögg J. A systematic review of the association between hospital cost/price and the quality of care. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(5):625–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00577-6.

Gani F, Ejaz A, Makary MA, Pawlik TM. Hospital markup and operation outcomes in the United States. Surgery. 2016;160(1):169–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.03.014.

Bai G, Anderson GF. Market power: price variation among commercial insurers for hospital services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(10):1615–22. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0567.

Cooper Z, Craig SV, Gaynor M, Van Reenen J. The price ain’t right? hospital prices and health spending on the privately insured*. Q J Econ. 2019;134(1):51–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjy020.

Roberts ET, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Market share matters: evidence of insurer and provider bargaining over prices. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0479.

Sinaiko AD, Joynt KE, Rosenthal MB. Association between viewing health care price information and choice of health care facility. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1868. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6622.

Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, et al. Offering a price transparency tool did not reduce overall spending among California public employees and retirees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1401–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1636.

Desai S, Hatfield LA, Hicks AL, Chernew ME, Mehrotra A. Association between availability of a price transparency tool and outpatient spending. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1874. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.4288.

Brown ZY. Equilibrium effects of health care price information. Rev Econ Stat. 2019;101(4):699–712. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00765.

Mehta R, Merath K, Farooq A, et al. U.S. news and world report hospital ranking and surgical outcomes among patients undergoing surgery for cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(8):1327–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25751.

DeLancey JO, Softcheck J, Chung JW, Barnard C, Dahlke AR, Bilimoria KY. Associations between hospital characteristics, measure reporting, and the centers for medicare & medicaid services overall hospital quality star ratings. JAMA. 2017;317(19):2015. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3148.

Silber JH, Satopää VA, Mukherjee N, et al. Improving medicare’s hospital compare mortality model. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(S2):1229–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12478.

Austin JM, Jha AK, Romano PS, et al. National hospital ratings systems share few common scores and may generate confusion instead of clarity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):423–30. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0201.

Cutler D, Dafny L. Designing transparency systems for medical care prices. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(10):894–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1100540.

Jiang JX, Polsky D, Littlejohn J, Wang Y, Zare H, Bai G. Factors associated with compliance to the hospital price transparency final rule: a national landscape study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07237-y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to report.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sankaran, R., O’Connor, J., Nuliyalu, U. et al. Payer-Negotiated Price Variation and Relationship to Surgical Outcomes for the Most Common Cancers at NCI-Designated Cancer Centers. Ann Surg Oncol 31, 4339–4348 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-15150-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-024-15150-x