Abstract

Background

Diabetes Mellitus is one of the four major non-communicable diseases causing about 4 million deaths in 2017. By 2040, low income countries are projected to experience 92% increase in mortality due to diabetes. Undiagnosed diabetes poses a public health concern with costly public health implications especially in Africa. It is therefore crucial to examine the burden and risk factors for diabetes at national level to inform policy and national programs.

Methods

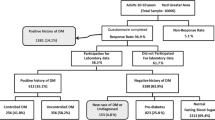

Data from the 2015 Kenya national STEPs survey of adults aged 18–69 years were used. Pre-diabetes was defined as impaired fasting blood glucose level (6.1 mmol/l to < 7 mmol/l) while diabetes was defined as impaired fasting blood glucose level ≥ 7 mmol/l. Descriptive statistics were used to determine the prevalence of pre-diabetes and diabetes and logistic regression was used to identify associated factors.

Results

Complete data for 4069 respondents (51% females), with 46% aged 18–29 and 61% in rural areas were analyzed. The age-standardized prevalence for pre-diabetes and diabetes were 3.1% (95% CI: 2.2, 4.0) and 2.4% (1.8, 3.0) respectively. Only 43.7% were aware of their glycemic condition, one in five of those who had diabetes had received treatment, and only 7% of those diagnosed with diabetes had their blood glucose under control. Primary education ((both incomplete (0.21, 95%CI 0.10–0.47) and complete (0.40, 95%CI 0.23–0.71)) were associated with lower odds of pre-diabetes. Older age (60–69 years, AOR; 5.6, 95%CI 2.1–15.1) and raised blood pressure (2.8, 95% CI 1.5–5.0) were associated diabetes while overweight/obesity among women was associated with diabetes.

Conclusion

The overall diabetes prevalence in Kenya is consistent with what has been reported in other sub-Saharan African countries. Of concern is the higher prevalence of pre-diabetes and undiagnosed diabetes that can progress to complications in the absence of interventions and the low diabetes awareness and control. This is the first nationally representative study to identify important groups at risk of pre-diabetes and diabetes that can be targeted for screening, health promotion and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes Mellitus is one of the four major non-communicable diseases (NCDs) comprising - cardiovascular diseases, cancers and chronic respiratory diseases jointly contributing to 63% of NCD deaths worldwide [1, 2]. From 1980 to 2014 the number of people living with diabetes globally increased from 108 million to 442 million [3, 4]. In 2017, the estimated figure had risen to 425 million people around the world and the majority were in low and middle income countries [5] with direct annual cost on the world estimated at US$825 billion [2]. Mortality from diabetes occurred every 8 seconds in 2017 estimated at 4 million among 20–79 year olds [5]. If the current diabetes trends continue unchanged, both the number of people living with diabetes and the deaths from diabetes are expected to increase. Low income countries are expected to experience the highest increase in diabetes prevalence (92%) followed by lower-middle income countries (57%), upper- middle income countries (46%) and higher income countries (25%) [3, 4, 6].

Undiagnosed cases of diabetes are a public health concern with costly public health implications. Globally, undiagnosed diabetes are common. Worldwide estimates for undiagnosed diabetes was 50% among people 20–79 years; the proportion of undiagnosed diabetes in Africa (69%) is almost double that of high-income countries (37%) [5]. This contributes to the high morbidity and mortality burden, which occurs at a younger age in Africa. Undiagnosed individuals with diabetes are likely to experience complications even before a diagnosis is made [5]. This can have additional cost implications for households [7] and on already overburdened health systems [8], thus a need to increase screening efforts worldwide to prevent the progression to diabetes.

Pre-diabetes, defined as glycemic levels that are higher than normal, but lower than diabetes thresholds (fasting glucose > 6·0 mmol/L and < 7·0 mmol/L) is considered an important risk factor for diabetes and its associated complications such as nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, and increased risk of macrovascular disease [4, 9,10,11]. Thus, understanding pre-diabetes is important for future diabetes projections. Some national studies in the US and China estimate adult pre-diabetes prevalence of 36.2% and 50.1%, respectively [12, 13]. One study projects that by 2030, 470 million people will have pre-diabetes globally [14]. Studies have suggested that progression to diabetes is occurring among those diagnosed with pre-diabetes. Tabak et al. suggested that the risk of people with pre-diabetes develo** diabetes is 5–10% per year [15]. Larson et al. in a study among postmenopausal women showed that 25% of subjects with impaired fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) test progressed to type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in 5 years [16]. However, there is also evidence indicating that managing pre-diabetes with lifestyle modifications such as physical activity [17] and healthy diets [18, 24] but lower than estimates (4%) by Christensen et al. in 2009 [20] and WHO in 2016 [35]. The possible differences in Christensen’s estimate and the current study is that the current study was a nationally representative sample while the Christensen’s sample was from a few selected ethnic grou**s in Kenya. Similarly, the WHO estimate is also based on multiple data sources and several assumptions are used to model the population estimate. Therefore, the results of the current study are more robust owing to nationally representative sample and a more reliable method of data collection. The diabetes prevalence (3.4%) in the urban population was slightly lower than the estimate (4.8–5.3%) reported in the slums of Nairobi [21, 22]. As the largest city, it is likely that Nairobi may be experiencing a faster epidemiological transition than other urban communities in Kenya.

Kenya’s diabetes prevalence of 2.4% is much higher than that of the neighboring country, Uganda with a prevalence of 1.4% from the recent STEPs survey [36]. The pre-diabetes prevalence of the current study was 3.1%. Malawi and Ghana reported diabetes cut off points that include the current study’s pre-diabetic sample and found a prevalence similar to the combined diabetes and pre-diabetes prevalence in the current study [37, 38]. Similar to studies conducted in Uganda [36] and South Africa [39] this study reported significantly higher diabetes prevalence in urban areas. This can be attributed to a faster epidemiological transition in urban areas associated with urbanization [40].

As observed in many settings [6, 41,42,43], pre-diabetes prevalence is higher than diabetes prevalence in our study. Available literature shows that persons with diabetes pass through a pre-diabetic phase during which if no prevention measures are instituted, they become diabetic [44, 45]. Pre-diabetes is a known risk factor for type 2 diabetes [46,47,48]. It is therefore critical to identify groups at risk of pre-diabetes for lifestyle changes to prevent progression to diabetes. In our study we identified two groups; both men and women with no formal education and women with high total cholesterol levels to be at risk of pre-diabetes. Any form of formal education was associated with lower odds of pre-diabetes as shown by studies in Sweden, China and other European countries [49,50,51]. Education improves access to relevant prevention messages and comprehension of such information thus influences health behaviors [52].

Diabetes on the other hand was associated with older age, raised blood pressure, and obesity among women as established in literature on metabolic syndrome [53]. The strong associations between advancing age and diabetes [20, 36], obesity and diabetes are well established [22]. A study by Wong-McClure found higher BMI and low education to be significantly associated with diabetes which is consistent with what the current study found [54].

The most worrying finding is the low level of awareness of diabetes among adults in Kenya with less than half the participants diagnosed with diabetes reporting that they were aware of their status. However, this is comparable to awareness levels found in most SSA countries suggesting poor access to screening services in these countries [23, 36, 55, 56]. While Kenya’s awareness level of 43.7% is low, it is lower than Uganda’s awareness level of 51.1% [36] but higher than Tanzania’s awareness level of 35.6% [57]. We found higher levels of awareness among urban residents, those from wealthier households but these were statistically insignificant. The high level of unawareness is worrying because of the impending diabetes complications that can be prevented if timely diagnosis is available for prompt management.

Our results also show that diabetes treatment levels are low. Only 21.3% of the patients with diabetes reported that they were on treatment while only 41% among those who were aware of their diagnosis were on treatment. The low levels of awareness of having diabetes is likely to contribute to low levels of treatment. The high treatment costs associated with diabetes care is also likely to contribute to the low treatment levels among those who are aware of their condition. A recent Lancet commission report on diabetes in SSA concluded that costs associated with diabetes treatment are high for patients in many countries since they mainly (> 50%) pay out-of-pocket [58]. The household expenditure and utilization survey in Kenya revealed only one in every five people seek and access health care and this was mainly due to the prohibitive treatment costs [59]. Women had a higher uptake of diabetes treatment than men as cited in a recent survey that revealed more frequent healthcare visits among women than men [59]. In addition to the frequent healthcare visits the higher treatment levels in women may be due to the higher awareness levels among women as well.

Glycemic control is important in prevention of complications and premature death. A study in the referral Kenyatta National Hospital showed a high case fatality in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis due to uncontrolled levels of glycaemia [60]. Our results show that glycemic control was only achieved by 7% of patients with diabetes and by 33% among those on treatment. These low control levels could be a result of the many factors including inaccessibility to tests and medications, low adherence to treatment regimens by the patients as well as drug stock outs increasing the number of patients missing prescribed medications. A meta-summary of diabetes in SSA found that inaccessibility to and the high cost of diabetes treatment was associated with poor glycemic control [23]. Similar to treatment levels, none of the patients with diabetes in the poorest households achieved glycemic control and this is also likely due to not accessing treatment. Diabetes control was significantly high among women and this could be due to the higher proportion of women being on treatment.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the use of a large national sample that has provided a complete national picture of diabetes situation in Kenya. The cross-sectional nature of this study precludes any causal association. The reliance of self-reported physical activity, dietary data and social behaviors may lead to incorrect estimates. Another potential limitation in a population based study such as this is the uncertainty of achieving a fasting state by the clients which could easily lead to an over-estimate of diabetes prevalence. However, during data collection, fasting blood samples were collected 1 day after the interview at a central hub to allow participants follow fasting advice given on the day of interview.

Conclusions

This study provides the first national estimate for pre-diabetes and diabetes in Kenya and adds to the body of knowledge on diabetes and pre-diabetes in the country. The study results suggest a slightly higher prevalence for pre-diabetes than diabetes prevalence with a high proportion of patients with undiagnosed diabetes. This study thus provides an opportunity to inform interventions aimed at preventing the progression from pre-diabetes to diabetes and to its complications. In 2013 the WHO’s Global Action Plan 2013–2020 for NCDs called for a halt in the rise of diabetes and a 25% relative reduction in risk of premature mortality due to diabetes by 2020 [61]. It is time to heed the call to action on diabetes made a decade ago by African researchers [23]. Towards this, there is need in Kenya to support increased efforts towards promotion and prevention of diabetes among those at risk including; those older than 30 years, and those with raised blood pressure. Guidelines should be provided to healthcare workers to screen for these risk factors among these populations and sensitize them on appropriate care. Additionally, access to treatment among diabetic adults in Kenya should be prioritized in order to prevent the development of complications and premature deaths associated with uncontrolled diabetes.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- IFG:

-

Impaired Fasting Glucose

- IGT:

-

Impaired Glucose Tolerance

- KEMRI:

-

Kenya Medical Research Institute

- KNBS:

-

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

- NASSEP:

-

National Sample Surveys and Evaluation Programme

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

References

World Health Organization, Regional High level Consultation; Tehran, 2010. Background Paper : Noncommunicable diseases in low-and middle income countries. 2010.

Forouzanfar MH, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724.

Collaboration, N.R.F. Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4· 4 million participants. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1513–30.

World Health Organization. Global report on diabetes: World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016.

International Diabetes Federation, IDF Diabetes Atlas Eight edition 2017. 2017.

Whiting DR, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(3):311–21.

Kankeu HT, et al. The financial burden from non-communicable diseases in low-and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2013;11(1):31.

World Health Organization, World Health Report, 2010: health systems financing the path to universal coverage. 2010.

Huang Y, et al. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. bmj. 2016;355:i5953.

World Health Organization. International Diabetes Federation: Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. 2006: Google Scholar; 2006.

Maritz, FJ. Insulin resistance and vascular disease. Journal of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa, 2004;9(2): p. 54–61.

Bullard KM, et al. Secular changes in U.S. Prediabetes prevalence defined by hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose: National Health and nutrition examination surveys, 1999-2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2286–93.

Ning G, Zhao W, Wang W. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. 2010 China noncommunicable disease surveillance group. JAMA. 2013;310:948–59.

Ligthart S, et al. Lifetime risk of develo** impaired glucose metabolism and eventual progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2016;4(1):44–51.

Tabák AG, et al. Prediabetes: a high-risk state for diabetes development. Lancet. 2012;379(9833):2279–90.

Larsson H, et al. Prediction of diabetes using ADA or WHO criteria in post-menopausal women: a 10-year follow-up study. Diabetologia. 2000;43(10):1224–8.

Gillies CL, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):299.

Muraki I, et al. Fruit consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective longitudinal cohort studies. BMJ. 2013;347.

** B, et al. Intake of fruit juice and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93471.

Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of glucose intolerance and associated risk factors in rural and urban populations of different ethnic groups in Kenya. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84(3):303–10.

Ayah R, et al. A population-based survey of prevalence of diabetes and correlates in an urban slum community in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):371.

Oti SO, et al. The magnitude of diabetes and its association with obesity in the slums of Nairobi, Kenya: results from a cross-sectional survey. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013;18(12):1520–30.

Azevedo M, Alla S. Diabetes in sub-saharan Africa: Kenya, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia. Int J Diabetes Dev Cries. 2008;28(4):101.

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Diabetes Atlas 7th Edition, 2015. 2016.

Riley L, et al. The World Health Organization STEPwise approach to noncommunicable disease risk-factor surveillance: methods, challenges, and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2015;106(1):74–8.

MOH KNBS & WHO. Kenya STEPwise Survey for Non-communicable diseases risk factors 2015 report. Nairobi; 2015. http://aphrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Steps-Report-NCD-2015.pdf.

National Cholesterol Education Program. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25): p. 3143–421.

Alderman M, et al. 1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Blood Press. 1999;8:9–43.

World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000.

World Health Organization, Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva, 8–11 December 2008. 2011.

World Health Organization, Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). Geneva. http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/steps/GPAQ%20Instrument%20and%20Analysis%20Guide%20v2.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and Public Health. Accessed 23 Apr 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.htm.

Drug and Alcohol Rehab in Thailand. What is Harmful Drinking Drug and Alcohol Rehab in Thailand. 2018; Accessed 25 Apr 2018. Available from: http://alcoholrehab.com/alcoholism/what-is-harmful-drinking/.

The DHS Program - Demographic and Health Surveys, Wealth Index Construction. 2017.

World Health Organization. Diabetes country profile; Kenya. 2016; Accessed 15 Jan 2018. Available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/country-profiles/ken_en.pdf.

Bahendeka S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes mellitus in Uganda: a population-based national survey. Tropical Med Int Health. 2016;21(3):405–16.

Msyamboza KP, Mvula CJ, Kathyola D. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes mellitus in Malawi: population-based national NCD STEPS survey. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14(1):41.

Nelson F, Nyarko KM, Binka FN. Prevalence of risk factors for non-communicable diseases for new patients reporting to Korle-Bu teaching hospital. Ghana Medical Journal. 2015;49(1):12–8.

Stokes A, et al. Prevalence and unmet need for diabetes care across the care continuum in a national sample of south African adults: evidence from the SANHANES-1, 2011-2012. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0184264.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Human Development Network, and The World Bank. The Global Burden of Disease: Generating Evidence, Guiding Policy — Sub-Saharan Africa Regional Edition. Seattle: IHME; 2013.

Agwanda A, Khasakhala A, Kimani M. Assessment of family planning services in Kenya: Evidence from the 2004 Kenya Service Provision Assessment Survey: Kenya Working Papers; Nairobi: 2009.

Mayega RW, et al. Diabetes and pre-diabetes among persons aged 35 to 60 years in eastern Uganda: prevalence and associated factors. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72554.

Meme N, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes among hypertensive patients attending Kiambu district hospital, Kenya: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22:286.

Lindström J, et al. The Finnish diabetes prevention study (DPS): lifestyle intervention and 3-year results on diet and physical activity. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3230–6.

Ambady R, Chamukuttan S. Early diagnosis and prevention of diabetes in develo** countries. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2008;9(3):193.

Chen K-T, et al. Impaired fasting glucose and risk of diabetes in Taiwan: follow-up over 3 years. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;60(3):177–82.

Coronado-Malagón M, et al. Progression toward type-2 diabetes mellitus among Mexican pre-diabetics. Assessment of a cohort. Gac Med Mex. 2009;145(4):269–72.

Meigs JB, et al. The natural history of progression from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes in the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. Diabetes. 2003;52(6):1475–84.

Agardh EE, et al. Burden of type 2 diabetes attributed to lower educational levels in Sweden. Popul Health Metrics. 2011;9(1):60.

Shang X, et al. Educational level, obesity and incidence of diabetes among Chinese adult men and women aged 18–59 years old: an 11-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66479.

Sacerdote C, et al. Lower educational level is a predictor of incident type 2 diabetes in European countries: the EPIC-InterAct study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(4):1162–73.

Scuteri A, et al. Education eclipses ethnicity in predicting the development of the metabolic syndrome in different ethnic groups in midlife: the study of Women’s health across the nation (SWAN). Diabet Med. 2008;25(12):1390–9.

Samson SL, Garber AJ. Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2014;43(1):1–23.

Wong-McClure R, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in Costa Rica: Costa Rican National Cardiovascular Risk Factors Survey, 2010. J Diabetes. 2016;8(5):686–92.

Hall V, et al. Diabetes in sub Saharan Africa 1999-2011: epidemiology and public health implications. A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:564.

Mbanya JCN, et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2254–66.

Stanifer JW, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and complications of diabetes in the Kilimanjaro region: a population-based study from Tanzania. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0164428.

Atun R, et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: from clinical care to health policy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(8):622–67.

Ministry of Health. 2013 Kenya Household Health Expenditure and Utilisation Survey. Nairobi; 2014.

Mbugua P, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis: clinical presentation and precipitating factors at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 2005;82(12 Suppl): p. S191–6.

World Health Organization, Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013–2020. 2013.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the individuals and organizations that provided technical support for the design and implementation of the main survey. The CORE funding for the main survey was provided by World Bank, WHO, AstraZeneca and MOH/CDC. Authors are also grateful to the data collection and analysis team led by the Ministry of Health, WHO and Kenya National Bureau of statistics, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD).

Funding

Analysis time and publication costs were funded by the International Development Research Center (IDRC) (grant # 107209–001).

Availability of data and materials

Study materials and de-identified data that support the findings in this study are available by contacting Gladwell Gathecha at the Ministry of Health Kenya at gladwellgathecha@gmail.com

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Public Health Volume 18 Supplement 3, 2018: Special issue from national survey on NCD risk factors in Kenya. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-18-supplement-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFM & MM conceived the study. SFM wrote the analysis plan. SFM & MM conducted the literature review and wrote the first draft manuscript. MKM did the analysis. GA contributed to the literature review. MKM, JK, AH, ZN, SO, GA, and CK reviewed the draft manuscript, provided input, critical comments. SFM finalized the manuscript which was subsequently approved by all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study approval was obtained from Kenya Medical Research Institute’s Ethics Review Committee (SSC No. 2607). Verbal informed consent was sought before enrollment in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, S.F., Mwangi, M., Mutua, M.K. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with pre-diabetes and diabetes mellitus in Kenya: results from a national survey. BMC Public Health 18 (Suppl 3), 1215 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6053-x

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6053-x