Abstract

Background

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric problems among Canadian youth and typically have an onset in childhood or adolescence. They are characterized by high rates of relapse and chronicity, often resulting in substantial impairment across the lifespan. Genetic factors play an important role in the vulnerability toward anxiety disorders. However, genetic contribution to anxiety in youth is not well understood and can change across developmental stages. Large-scale genetic studies of youth are needed with detailed assessments of symptoms of anxiety disorders and their major comorbidities to inform early intervention or preventative strategies and suggest novel targets for therapeutics and personalization of care.

Methods

The Genetic Architecture of Youth Anxiety (GAYA) study is a Pan-Canadian effort of clinical and genetic experts with specific recruitment sites in Calgary, Halifax, Hamilton, Toronto, and Vancouver. Youth aged 10–19 (n = 13,000) will be recruited from both clinical and community settings and will provide saliva samples, complete online questionnaires on demographics, symptoms of mental health concerns, and behavioural inhibition, and complete neurocognitive tasks. A subset of youth will be offered access to a self-managed Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy resource. Analyses will focus on the identification of novel genetic risk loci for anxiety disorders in youth and assess how much of the genetic risk for anxiety disorders is unique or shared across the life span.

Discussion

Results will substantially inform early intervention or preventative strategies and suggest novel targets for therapeutics and personalization of care. Given that the GAYA study will be the biggest genomic study of anxiety disorders in youth in Canada, this project will further foster collaborations nationally and across the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anxiety disorders are currently the most prevalent class of psychiatric disorders worldwide, impacting an estimated 4.1% of 10-19-year-olds [1]. Canadian youth have an estimated six-month prevalence of 11 to 15% [2] with the most frequent diagnoses being separation anxiety disorder, specific phobias, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and agoraphobia. Over the last three decades, a steep increase in the prevalence of anxiety disorders has been observed [3]. Considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [4], this trend is likely to continue [5]. These disorders typically have an early onset in childhood/adolescence resulting in substantial impairment across the lifespan [6,7,8,9].

Anxiety disorders commonly co-occur; multiple correlations have been identified among different anxiety disorders [10], particularly between agoraphobia and social anxiety disorder (r = 0.68), panic disorder (r = 0.64), and specific phobia (r = 0.57), and specific phobia and social anxiety disorder (r = 0.50). High current and lifetime comorbidities are also observed with other psychiatric disorders, especially depression as over 50% of individuals with depressive disorders report a history of an anxiety disorder [11]. Substantial overlap has also been observed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), substance use disorders, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [10].

Both genetic and environmental factors play an important role in the intricate pathogenesis of anxiety disorders; in particular, genetic factors account for the moderate stability of anxiety disorders across the lifespan [12]. Current heritability estimates converge to rates around 35% for GAD and around 50% for social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and agoraphobia [13]. The mode of inheritance is complex, with many genetic variants of small effect interacting with, or adding to other (environmental) risk factors [14, 15]. Importantly, heritability estimates of child and adult anxiety measures differ [16]. Longitudinal twin studies suggest that heritability is high in childhood but decreases over adolescence and into adulthood [12, 17, 18]. The genetic structure of anxiety disorders also seems to change across development. Anxiety subtypes in adults seem to fit a 2-factor model characterized by distress (GAD and depression) and fear (panic disorder and specific phobias) [19], but different structures have been found in youth with different genetic influences on anxiety and depression in childhood, common genetic vulnerability for anxiety and depression emerging in adolescence, and broadening associations in young adulthood [20].

The most well-researched source of genetic variation known to influence the risk of psychiatric disorders are common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Genome-wide association study (GWAS), which enables the search for risk variants across the genome, is ideally suited to study common genetic risk factors for polygenic conditions such as anxiety disorders. GWAS for specific anxiety disorders and traits were historically severely underpowered [13]. To overcome sample size limitations, researchers started analyzing disorder subtypes together. By meta-analyzing the results of 7 GWAS on 5 clinically ascertained anxiety disorder subtypes (n = 17,310), the ANGST Consortium study [21] identified 2 genome-wide significant loci. A GWAS in the UK biobank on composite anxiety phenotypes using self-reported symptoms and diagnoses (n = 83,566) identified 5 genome-wide significant loci [22]. In addition, the largest anxiety GWAS to date was performed in 175,163 European and 24,448 African military veterans using a 2-item dimensional measure of GAD [23]. The study identified 6 significant loci for anxiety in European Americans and one in African Americans. But GWAS studies of anxiety phenotypes in youth have thus far been unsuccessful in identifying any genome-wide significant loci due to reasons such as low power and heterogeneity [24,25,26].

Genetic correlations can guide our understanding of the nature and patterns underlying complex traits and disorders. Large GWAS of anxiety disorders show strong positive genetic correlations with major depressive disorder (MDD) (rG = 0.78) [22, 23]. Accounting for comorbid MDD results in diminished but still significant SNP-based heritability for anxiety symptoms [23], indicating shared but also specific genetic effects of MDD and anxiety. Genetic correlations have additionally been observed between anxiety and other psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, ADHD), sleep, and cardiometabolic traits and risk factors [22, 23]. GWAS of internalizing disorders in youth showed strong genetic correlations (rG > 0.7) with adult anxiety. However, the observed correlations with adult anxiety disorders were partial rather than complete, indicating that from a developmental perspective, childhood/adolescent internalizing symptoms are not genetically identical to adult anxiety or depression [25]. Given these differences, further clarification of specific genetic contributions to youth anxiety is needed.

Behavioural and cognitive traits, particularly behavioral inhibition (BI), inhibitory control and avoidance, are known to confer risk to later development of anxiety disorders. BI is a strong vulnerability marker of anxiety [27, 28] and is defined as an early childhood temperament characterized by shyness, fear, negative reactions to novelty, and avoidance of unfamiliar contexts or people [29,30,31]. Although BI is the best-known risk factor for anxiety disorders and associated with a 4–6 fold increased risk [32], only an estimated 40% of behaviourally inhibited children will develop anxiety disorders [33]. Research suggests that inhibitory control (the ability to inhibit responses to goal-irrelevant stimuli) plays a moderating role in the trajectory from childhood BI to adulthood anxiety disorders. For example, youth who inhibit their impulses best typically develop anxiety disorders in adulthood [34, 35], thus highlighting the need to assess both BI and inhibitory control in youth. Avoidance of stimuli or situations perceived as dangerous or threatening is a cardinal feature of anxiety disorders. This avoidance is self-reinforcing, sha** further retreat over time [36]. Avoidance is a primary intervention target. At its core, avoidant behavior is fueled by a desire to avoid danger, a feature that makes anxious youth vigilant for threat and prone to exaggerate their interpretations of it. Risk avoidance is well studied in anxious adults [37, 38] and, to a lesser extent, in youth with anxiety [39,40,41]. Among factors that drive avoidant behavior, the aversion to risky behaviours might be of particular relevance in the etiology of anxiety disorders. Measuring inhibitory control and risk tolerance in the context of anxiety could help elucidate cognitive mechanisms underlying youth anxiety.

The first-line treatment option for anxiety disorders in youth is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [42]. CBT involves psychoeducation about anxiety, teaches youth skills for managing fears (e.g., relaxation, cognitive restructuring, problem solving), and helps youth to gradually face their fears while minimizing avoidance (i.e., exposure) [43]. The effectiveness of CBT (face-to-face or online) for youth anxiety has been demonstrated in several randomized control trials indicating large pre- to post- treatment effects and demonstrating superiority over control conditions [44, 45]. Valid second line treatment options are medication monotherapy, i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [46], as well as the combination of CBT and medication [47, 48]. Nonetheless, one in three youth fail to respond to existing treatments [49], and few remain in remission [50]. Many youths also do not seek and/or receive treatment [2]. Given that genetic risk factors can affect the clinical response of patients [51], the emerging field of therapygenetics may be particularly important in predicting treatment outcomes. Unfortunately, to date, samples of youth undergoing CBT for anxiety disorders are difficult to recruit and retain, and these analyses have so far been underpowered [52,53,54].

Methods

Aims

In the current article we outline the design and methods of the GAYA study that aims to better understand the genetic underpinnings of anxiety disorders in Canadian youth. The GAYA study will help close the above-identified gaps in existing research in youth anxiety through a framework of integrated specific aims that will enhance our understanding of the specific genetic contributions to anxiety from childhood through adolescence, and implications for treatment. The specific aims and hypotheses are outlined in Table 1.

Participants

The study will make use of a population-based design enriched for youth with anxiety disorders as this sampling scheme has been shown to result in the highest power per included individual for quantitative and categorical traits with limited risk of biases [55,56,57,58]. The goal is to recruit 13,000 youth aged 10–19 of which 50% are expected to endorse symptoms of anxiety that indicate the presence of an anxiety disorder. This will be achieved by sampling from clinical settings as well as the general population. Youth will be recruited across Canada to the GAYA study with local sites in Calgary, Halifax, Hamilton, and Vancouver. The Toronto site will recruit from existing participants of Spit for Science [110] and lower numbers indicating increased risk avoidance.

As youth with anxiety disorders are likely to be affected by the presence of an unknown examiner [111], and to increase accessibility, we developed the GAYA app for administering the neurocognitive tasks. Co- designed with youth, the GAYA app allows youth participants to complete the tasks remotely in an environment of their choosing. The app can be installed on smartphones and tablets with iOS or Android operating systems. Participating youth will be provided with a download link for the app and their personal login credentials by the study team.

Saliva samples

Saliva sample collection will follow established protocols. Saliva-derived DNA has been shown to perform nearly as well as blood DNA [112, 113] and is routinely used in large-scale genetic studies in youth [60]. Youth will be invited to provide saliva samples at the nearest individual recruitment sites (Calgary, Halifax, Hamilton, or Vancouver) with an OG-600 Oragene saliva DNA sample kit or choose to have an OCR-100 ORAcollect DNA sample kit mailed to their home with a pre-paid return envelope. De-identified research IDs will link data and saliva samples. The linked IDs will be logged in REDCap to document and track the handling of biologic samples. Participants will be instructed on how to provide a sample by a trained research staff member via live video or a pre-recorded video and receive written instructions. Toronto participants will have already provided their saliva samples at the time of participating in Spit for Science using OG-600 Oragene saliva DNA sample kits.

Optional intervention

Intervention procedures

Youth enrolled in GAYA who are ages 13–19, not currently in mental health treatment, and do not endorse psychosis screening questions will be offered the opportunity to participate in a self-managed Internet-based CBT (iCBT) program, Breathe (Being Real, Easing Anxiety: Tools Hel** Electronically) [114], at all recruitment sites. These youth will be linked to the Strongest Families Institute (SFI, http://strongestfamilies.com/), where all referred youth will receive the Breathe program that is part of SFI’s validated eplatform IRIS (Intelligent Research and Intervention Software).

Through weekly self-managed check-ins, during which youth assess and rate their social-emotional functioning over the past week, a detailed monitoring of anxiety symptoms over the course of the Breathe program will be enabled. Youth will also be asked to rate their anxiety symptoms based on the SCARED pre-, post-treatment, and at a 3 months follow-up. Intervention response will be defined as the changes in SCARED scores from pre- to post-treatment for the 3 months follow-up.

Breathe intervention description

Breathe is a self-mediated 6-module standardized iCBT program that involves: (a) multimedia-based education about anxiety problems and approaches to overcoming anxiety (e.g., reviewing why exposure exercises are important); (b) self-assessment activities to determine level of intervention and safety needs; (c) activities that teach users about anxiety sensitivity and how to develop realistic thinking about anxiety-producing situations; (d) activities for practicing co** and relaxation skills; (e) development of a hierarchy of feared situations and steps for gradual and repeated exposure to feared situations (using imagery/in vivo activities); (f) contingency management (examining the function of anxiety from a reinforcement perspective) and modelling (viewing videos of others confronting feared situations); and (g) skills for maintenance and relapse prevention. Animations, embedded videos, timed prompts, and on-screen pop-ups are used in each module to provide an interactive and multimodal experience. In one of the largest effectiveness trials of iCBT in adolescents conducted to date, that used SFI’s IRIS eplatform, 563 adolescents aged 13–19 were randomly assigned to 6 weeks of Breathe (n = 280) or to visit a static (no elements of interactivity or personalization) website which provided resources for anxiety (n = 283) [115]. In the trial, adolescents who participated in Breathe had a greater improvement in symptoms 3 months after program use (p = 0.04) [115]. Although this Breathe study was complimented by one telephone coach support session to those who wanted the additional support, the current study will only be self-mediated.

Collection of biomaterials, DNA extraction and genoty** process

DNA extraction from saliva is performed at each individual site following best practice and according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Subsequent genoty** will be performed in 3 batches. All individuals will be genotyped (using DNA from the saliva samples) with Illumina’s Global Screening Array v3.0 (GSA). The GSA is a cost-effective genoty** array that is routinely used for population-scale genetic studies around the globe. For genoty** calling Illumina’s GenomeStudio will be used. Spit for Science genoty** will be done locally using the same Illumina array and their genetic data is sent to the Halifax site once the participant has completed the questionnaires and/or app portion of the study.

Quality control (QC) and imputation of GWAS data

The Ricopili pipeline will be used to perform QC of the genetic data within and across ancestral stratified subgroups (based on demographic information) [116]. Ricopili has been extensively used by international consortia for their large-scale GWAS and makes use of well-established analytic software during its processing steps (e.g., PLINK [116]). Analyses will look for any (hidden) relatedness or sample duplicates as part of our QC and flag individuals that are related (pi_hat > 0.2) for downstream analyses. Population substructure will be (re-) examined by principal components (PC) estimation and support vector machines will be run in joined PC analyses with a reference sample of known ancestral background (TopMed) to annotate the sample with population substructure information and compare this information with the demographic information collected during the online assessment. For imputation, a pre-phasing/imputation stepwise approach as implemented in Ricopili [117] will be used with and across population subgroups identified in our sample. This will include the evaluation of a potential increase in power through usage of imputation approaches that use local ancestry to enable inclusion of admixed individuals in the GWAS [118]. ChrX imputation will be conducted separately by sex for subjects passing an additional QC designed for these purposes [119]. For downstream analyses SNPs that have an INFO > 0.8 and a MAF > 0.01 will be considered.

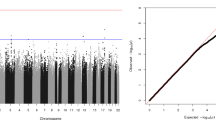

Data analysis strategy

Appropriate covariates (e.g., age, sex, gender, recruitment procedure/site) will be included for analyses in each trait. Where necessary and appropriate analyses will control for current/past treatment history through established protocols. For all GWAS, the impact of population substructure on the genome-wide test statistics using λGC [120] and Linkage Disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) analyses [121] will be evaluated. There are clear sex differences described in the epidemiology of anxiety. Anxiety disorders and symptoms occur more often in women, and the odds of develo** an anxiety disorder is 1.7 times greater for women than men [122]. The analyses will therefore be stratified by sex and gender to explore shared and unique genetic contributions.

Data analysis will be aligned with each of the specific aims. For all results identified in aims 1–4, using MAGMA [123] and LDSC [124] tissue and single cell enrichment analyses will be conducted compiling publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing data from five studies of the human and mouse brain [125,126,127,128]. Similarly, transcriptome-wide association studies will be conducted using FUSION [129] and expression quantitative trait locus data from the PsychENCODE Consortium (1,321 brain samples) [130]. In addition, analyses will include EpiXcan [131], an elastic net-based method, which weighs SNPs based on epigenetic annotation information [132].

Specific aim 1: identify genetic risk factors associated with clinical symptoms and vulnerability markers of youth anxiety

Following best practices in the field, additive model GWAS analyses will be conducted for common SNPs and each quantitative trait. To increase power, multivariate-based approaches will be employed that enable us to address the complex relationship of the anxiety phenotypes (SCARED subscales, BIS/BAS subscales, inhibitory control, and risk avoidance) amongst each other but also in relationship to the genetic data. As such the GW-SEM software package [133, 134] will be used. Genome-wide results from GAYA study samples will be meta-analysed with other available samples [25, 61] using inverse-variance weighting with METAL [135] and accounting for population structure. Sensitivity analyses using structural equation modelling (SEM), via genomic SEM, will help to address potential heterogeneity. Established approaches (LDSC [120] and GCTA [136]) will be used to study liability-scale heritability of clinical symptoms and vulnerability markers of youth anxiety. Partitioned heritability across minor allele frequency bins and functional annotations (e.g., cell-types) using the same software packages and publicly available data (e.g., from the PsychENCODE consortium [137]) will provide further insights into the genetic relationship of different clinical symptoms and vulnerability.

Specific Aim 2: identify genetic factors that are unique to anxiety in different age groups

Multi-trait conditional and joint analysis [138] to adjust GWAS summary statistics from the GWAS in youth for the genetic effects in adult anxiety to identify putative age group-specific SNP associations. It is noteworthy that previous analyses in closely related traits of similar sample size (e.g., ADHD) were able to identify new genome-wide significant hits specific to the traits under analysis [138]. Similarly, summary statistics from youth and adult anxiety GWASs will be analysed with ccGWAS [139], a tool designed to identify loci with different allele frequencies among different trait groups. Using ccGWAS genetic loci will be identified that are specific in their association to the individual age groups.

Using established protocols (SBayesR [140]/LDpred2 [141]/PRSice2 [142]) genomic risk profile scores (GRPS) will be generated in the GAYA study sample trained on discovery datasets from different age groups (i.e., pairwise between the youth and adult GWAS) to assess the variance explained through genetic liability for anxiety disorders in one age group for the other. Finally, where appropriate, CLiP [143] will be used to study heterogeneity in GRPS for the GAYA study sample.

Specific aim 3: identify genetic factors that are shared and unique between anxiety and its common comorbidities

Via LDSC [120] patterns of genetic correlation, common comorbidities (e.g., MDD, ADHD) with youth anxiety will be analyzed. Genomic SEM will be run including the youth anxiety GWAS along with the newest adult anxiety GWAS [21,22,23] to investigate the multivariate genetic architecture across youth anxiety and its comorbidities. In this multivariate GWAS, it will be possible to identify loci that confer risk to multiple disorders (i.e., that are shared across disorders).Two-sample Mendelian Randomization (MR) analyses will be conducted using the inverse-variance-weighted (IVW) MR method to investigate associations between the genetic liability for youth anxiety and adult-onset mental disorders, while further ensuring the robustness of our IVW estimates through MREgger and the MR robust adjusted profile score approach [144, 145].

Specific aim 4: identify a prediction model of treatment response in youth with anxiety disorders

GWAS data for general susceptibility for major psychiatric illnesses (such as adult and youth anxiety, MDD, ADHD, and others), and antidepressant treatment response [146] will be used to train GRPS in the GAYA study sample. For each of these GRPS the amount of variation explained in the clinical response of youth receiving Breathe will be assessed. It will also be evaluated how much of this variation can be explained by clinical symptoms/vulnerability markers and subsequently whether the combination of these measures (i.e., GRPS plus clinical symptoms/vulnerability markers) can increase our ability to predict clinical response in youth with anxiety disorders. Further, explorative GWAS will be conducted in two datasets: (a) 3,000 youth recruited to receive CBT and (b) around 10,000 individuals (all age groups, including the 3,000 youth) by combining the GAYA study sample with samples available via collaborations [52, 61].

Youth council

A national youth council, including members of established youth councils at study sites, will consult through all phases of the design and management of the study. Meetings will be conducted virtually to allow for geographic diversity and youth council recruitment will prioritize representation of diverse demographics. Youth will advise on several aspects of GAYA, including recruitment strategies (i.e., flyers and posters); contact management and retention tools; study measures and instruments; assessment instrument package; and the assessment package’s length and readability. Additionally, as part of the knowledge translation plan, youth will be included in the interpretation of findings and their presentation through various knowledge translation activities, such as presentations, publications, short videos, infographics, and webinars co-led by youth.

Discussion

While anxiety disorders have become more common in youth over the years and exacerbated by the pandemic, efforts aiming to explore the genetic underpinnings of anxiety disorders are limited. Twin studies strongly suggest that genetic susceptibility plays a role in the development of anxiety disorders and that this role is age-dependent [12, 17, 18] Thus, the GAYA study has the potential to fill an important gap in our current knowledge. Study results will significantly contribute to a better understanding of the developmental trajectory of anxiety disorders and its common comorbidities, increasing knowledge in relation to the high rates of co-occurrence observed across psychiatric disorders [22, 23]. As analyses of youth undergoing CBT for anxiety disorders have been previously underpowered [52,53,54], the GAYA study’s sample size will further inform prediction models of treatment response. Finally, study results are expected to inform early intervention or preventative strategies and suggest novel targets for therapeutics and personalization of care.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- BART:

-

Balloon Analogue Risk Task

- BI:

-

Behavioral inhibition

- BAS:

-

Behvaioural Activation System

- BIS:

-

Behavioural Inhibition System

- Breathe:

-

Being Real, Easing Anxiety: Tools Hel** Electronically

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- CPSS-SR:

-

Child PTSD Symptom Scale self–report

- GAD:

-

Generalized anxiety disorder

- GAYA:

-

Genetic Architecture of Youth Anxiety

- GRPS:

-

Genomic risk profile scores

- GSA:

-

Global Screening Array

- GWAS:

-

Genome wide association study

- iCBT:

-

Internet–based cognitive behavioral therapy

- IRIS:

-

Intelligent Research and Intervention Software

- IUS-12:

-

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale

- IVW:

-

Inverse–variance–weighted

- LDSC:

-

Linkage Disequilibrium score regression

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- MR:

-

Mendelian Randomization

- OCD:

-

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

- OCI-CV:

-

Obsessive–Compulsive Inventory–Child Version Scale

- PC:

-

Principal components

- PTSD:

-

Post–traumatic stress disorder

- QC:

-

Quality control

- SCARED:

-

Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modelling

- SFI:

-

Strongest Families Institute

- SHS:

-

Subjective Happiness Scale

- SMFQ:

-

Short Mood and Feeling Questionnaire

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SOP:

-

Standard operating procedure

- SWAN:

-

The Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and Normal Behaviour Rating Scale

- TOCS:

-

Toronto Obsessive–Compulsive Scale

References

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) data input sources tool. Accessed July 18., 2023. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2019/data-input-sources.

Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Comeau J, Boyle MH. Six-Month Prevalence of Mental disorders and Service contacts among children and youth in Ontario: evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2019;64(4):246–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719830024.

Comeau J, Georgiades K, Duncan L, Wang L, Boyle MH, 2014 Ontario Child Health Study Team. Changes in the prevalence of child and Youth Mental disorders and Perceived need for Professional help between 1983 and 2014: evidence from the Ontario Child Health Study. Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2019;64(4):256–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743719830035.

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482.

Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(4):671–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3.

Ginsburg GS, Becker EM, Keeton CP, et al. Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):310–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4186.

Ginsburg GS, Becker-Haimes EM, Keeton C, et al. Results from the Child/Adolescent anxiety Multimodal Extended Long-Term Study (CAMELS): primary anxiety outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(7):471–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.03.017.

Ferro MA, Gorter JW, Boyle MH. Trajectories of depressive symptoms during the transition to young adulthood: the role of chronic illness. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:594–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.12.014.

Curry J, Silva S, Rohde P, et al. Recovery and recurrence following treatment for adolescent major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(3):263–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.150.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617.

Hirschfeld RMA. The comorbidity of major depression and anxiety disorders: Recognition and Management in Primary Care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(6):244–54. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v03n0609.

Hannigan LJ, Walaker N, Waszczuk MA, McAdams TA, Eley TC. Aetiological influences on stability and change in emotional and behavioural problems across development: a systematic review. Psychopathol Rev. 2017;4(1):52–108. https://doi.org/10.5127/pr.038315.

Meier SM, Deckert J. Genetics of anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(3):16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1002-7.

Solmi M, Dragioti E, Arango C, et al. Risk and protective factors for mental disorders with onset in childhood/adolescence: an umbrella review of published meta-analyses of observational longitudinal studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;120:565–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.09.002.

Costa E, Silva JA, Steffen RE. Urban environment and psychiatric disorders: a review of the neuroscience and biology. Metabolism. 2019;100S:153940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2019.07.004.

Polderman TJC, Benyamin B, de Leeuw CA, et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(7):702–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3285.

Nivard MG, Dolan CV, Kendler KS, et al. Stability in symptoms of anxiety and depression as a function of genotype and environment: a longitudinal twin study from ages 3 to 63 years. Psychol Med. 2015;45(5):1039–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171400213X.

Waszczuk MA, Zavos HMS, Gregory AM, Eley TC. The stability and change of etiological influences on depression, anxiety symptoms and their co-occurrence across adolescence and young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2016;46(1):161–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001634.

Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: a quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(4):522–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522.

Waszczuk MA, Zavos HMS, Gregory AM, Eley TC. The phenotypic and genetic structure of depression and anxiety disorder symptoms in childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(8):905–16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.655.

Otowa T, Hek K, Lee M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21(10):1391–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.197.

Purves KL, Coleman JRI, Meier SM, et al. A major role for common genetic variation in anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(12):3292–303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0559-1.

Levey DF, Gelernter J, Polimanti R, et al. Reproducible Genetic Risk Loci for anxiety: results from ∼200,000 participants in the million veteran program. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(3):223–32. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030256.

Benke KS, Nivard MG, Velders FP, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of preschool internalizing problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(6):667–676e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.028.

Jami ES, Hammerschlag AR, Ip HF, et al. Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Childhood and adolescent internalizing symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(7):934–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.11.035.

Trzaskowski M, Eley TC, Davis OSP, et al. First genome-wide association study on anxiety-related behaviours in childhood. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e58676. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058676.

Fox NA, Zeytinoglu S, Valadez EA, Buzzell GA, Morales S, Henderson HA. Annual Research Review: developmental pathways linking early behavioral inhibition to later anxiety. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;64(4):537–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13702.

Sandstrom A, Uher R, Pavlova B. Prospective Association between childhood behavioral inhibition and anxiety: a Meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2020;48(1):57–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00588-5.

Fox NA, Buzzell GA, Morales S, Valadez EA, Wilson M, Henderson HA. Understanding the emergence of social anxiety in children with behavioral inhibition. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(7):681–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.10.004.

Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:235–62. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532.

Kagan J, Snidman N, Zentner M, Peterson E. Infant temperament and anxious symptoms in school age children. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(2):209–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579499002023.

Klein DN, Finsaas MC. The Stony Brook temperament study: early antecedents and pathways to Emotional disorders. Child Dev Perspect. 2017;11(4):257–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12242.

Henderson HA, Pine DS, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and developmental risk: a Dual-Processing Perspective. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):207–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2014.189.

Cardinale EM, Subar AR, Brotman MA, Leibenluft E, Kircanski K, Pine DS. Inhibitory control and emotion dysregulation: a framework for research on anxiety. Dev Psychopathol. 2019;31(3):859–69. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000300.

Tang A, Crawford H, Morales S, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Fox NA. Infant behavioral inhibition predicts personality and social outcomes three decades later. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(18):9800–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1917376117.

LeDoux JE, Moscarello J, Sears R, Campese V. The birth, death and resurrection of avoidance: a reconceptualization of a troubled paradigm. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(1):24–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.166.

Mueller EM, Nguyen J, Ray WJ, Borkovec TD. Future-oriented decision-making in generalized anxiety disorder is evident across different versions of the Iowa Gambling Task. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2010;41(2):165–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.12.002.

Giorgetta C, Grecucci A, Zuanon S, et al. Reduced risk-taking behavior as a trait feature of anxiety. Emot Wash DC. 2012;12(6):1373–83. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029119.

Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(1):3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3.

Pailing AN, Reniers RLEP. Depressive and socially anxious symptoms, psychosocial maturity, and risk perception: associations with risk-taking behaviour. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202423. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202423.

Rosen D, Patel N, Pavletic N, Grillon C, Pine DS, Ernst M. Age and Social Context modulate the effect of anxiety on risk-taking in Pediatric samples. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(6):1161–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0098-4.

Creswell C, Waite P, Cooper PJ. Assessment and management of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(7):674–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-303768.

Kendall PC, Peterman JS. CBT for adolescents with anxiety: mature yet still develo**. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):519–30. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14081061.

Zhou X, Zhang Y, Furukawa TA, et al. Different types and acceptability of psychotherapies for Acute anxiety disorders in Children and adolescents: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(1):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3070.

McGrath PJ, Lingley-Pottie P, Thurston C, et al. Telephone-based mental health interventions for child disruptive behavior or anxiety disorders: randomized trials and overall analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(11):1162–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2011.07.013.

Locher C, Koechlin H, Zion SR, et al. Efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and Placebo for Common Psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(10):1011–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2432.

Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804633.

Wang Z, Whiteside SPH, Sim L, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for childhood anxiety disorders: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):1049–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.3036.

Strawn JR, Levine A. Treatment response biomarkers in anxiety disorders: from neuroimaging to Neuronally-Derived Extracellular vesicles and Beyond. Biomark Neuropsychiatry. 2020;3:100024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bionps.2020.100024.

Rosenbaum J. New directions in anxiety disorder treatment. Gen Psychiatry. 2019;32(6):e100166. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2019-100166.

Deckert J, Erhardt A. Predicting treatment outcome for anxiety disorders with or without comorbid depression using clinical, imaging and (epi)genetic data. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000468.

Rayner C, Coleman JRI, Purves KL, et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of prognostic outcomes following cognitive behavioural therapy in individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):150. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0481-y.

Coleman JRI, Lester KJ, Keers R, et al. Genome-wide association study of response to cognitive-behavioural therapy in children with anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2016;209(3):236–43. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.168229.

Keers R, Coleman JRI, Lester KJ, et al. A genome-wide test of the Differential susceptibility hypothesis reveals a genetic predictor of Differential response to psychological treatments for child anxiety disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(3):146–58. https://doi.org/10.1159/000444023.

Pedersen CB, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Pedersen MG, et al. The iPSYCH2012 case–cohort sample: new directions for unravelling genetic and environmental architectures of severe mental disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.196.

Li Y, Levran O, Kim J, Zhang T, Chen X, Suo C. Extreme sampling design in genetic association map** of quantitative trait loci using balanced and unbalanced case-control samples. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15504. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51790-w.

Yang J, Wray NR, Visscher PM. Comparing apples and oranges: equating the power of case-control and quantitative trait association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34(3):254–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.20456.

Peyrot WJ, Boomsma DI, Penninx BWJH, Wray NR. Disease and Polygenic Architecture: avoid Trio Design and appropriately account for unscreened control subjects for Common Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98(2):382–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.12.017.

Burton CL, Lemire M, **ao B, et al. Genome-wide association study of pediatric obsessive-compulsive traits: shared genetic risk between traits and disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):91. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01121-9.

Crosbie J, Arnold P, Paterson A, et al. Response inhibition and ADHD traits: correlates and heritability in a community sample. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(3):497–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9693-9.

Davies MR, Kalsi G, Armour C, et al. The genetic links to anxiety and depression (GLAD) study: online recruitment into the largest recontactable study of depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2019;123:103503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103503.

Baiden P, Tadeo SK, Peters KE. The association between excessive screen-time behaviors and insufficient sleep among adolescents: findings from the 2017 youth risk behavior surveillance system. Psychiatry Res. 2019;281:112586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112586.

Abi-Jaoude E, Naylor KT, Pignatiello A. Smartphones, social media use and youth mental health. CMAJ. 2020;192(6):E136–41. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190434.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inf. 2019;95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

Birmaher B, Brent DA, Chiappetta L, Bridge J, Monga S, Baugher M. Psychometric properties of the screen for child anxiety related Emotional disorders (SCARED): a replication study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(10):1230–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199910000-00011.

Boyd RC, Ginsburg GS, Lambert SF, Cooley MR, Campbell KDM. Screen for child anxiety related Emotional disorders (SCARED): psychometric properties in an African-American parochial high school sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(10):1188–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200310000-00009.

Gonzalez A, Weersing VR, Warnick E, Scahill L, Woolston J. Cross-ethnic measurement equivalence of the SCARED in an outpatient sample of African American and non-hispanic white youths and parents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 53. 2012;41(3):361–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.654462.

Desousa DA, Salum GA, Isolan LR, Manfro GG. Sensitivity and specificity of the screen for child anxiety related Emotional disorders (SCARED): a community-based study. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2013;44(3):391–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0333-y.

Costello EJ, Angold A. Scales to assess child and adolescent depression: checklists, screens, and nets. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(6):726–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198811000-00011.

Brahm P, Cortázar A, Fillol MP, Mingo MV, Vielma C, Aránguiz MC. Maternal sensitivity and mental health: does an early childhood intervention programme have an impact? Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):226–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmv071.

Thapar A, McGuffin P. Validity of the shortened Mood and feelings Questionnaire in a community sample of children and adolescents: a preliminary research note. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81(2):259–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00073-0.

Turner N, Joinson C, Peters TJ, Wiles N, Lewis G. Validity of the short Mood and feelings Questionnaire in late adolescence. Psychol Assess. 2014;26(3):752–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036572.

Sharp C, Goodyer IM, Croudace TJ. The short Mood and feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ): a unidimensional item response theory and categorical data factor analysis of self-report ratings from a community sample of 7-through 11-year-old children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2006;34(3):379–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-006-9027-x.

Fernández-Martínez I, Morales A, Méndez FX, Espada JP, Orgilés M. Spanish adaptation and Psychometric properties of the parent version of the short Mood and feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ-P) in a non-clinical sample of Young School-aged children. Span J Psychol. 2020;23:e45. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.47.

Lerthattasilp T, Tapanadechopone P, Butrdeewong P. Validity and reliability of the Thai Version of the short Mood and feelings Questionnaire. East Asian Arch Psychiatry off J Hong Kong Coll Psychiatr Dong Ya **g Shen Ke Xue Zhi **anggang **g Shen Ke Yi Xue Yuan Qi Kan. 2020;30(2):48–51. https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1875.

Gillihan SJ, Aderka IM, Conklin PH, Capaldi S, Foa EB. The child PTSD Symptom Scale: Psychometric properties in female adolescent sexual assault survivors. Psychol Assess. 2013;25(1):23–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029553.

Foa EB, Asnaani A, Zang Y, Capaldi S, Yeh R. Psychometrics of the child PTSD Symptom Scale for DSM-5 for trauma-exposed children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 53. 2018;47(1):38–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1350962.

Løkkegaard SS, Elmose M, Elklit A. Validation of the diagnostic infant and Preschool Assessment in a Danish, trauma-exposed sample of young children. Scand J Child Adolesc Psychiatry Psychol. 2019;7:39–51. https://doi.org/10.21307/sjcapp-2019-007.

Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67(2):319–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319.

Yu R, Branje SJT, Keijsers L, Meeus WHJ. Psychometric characteristics of Carver and White’s BIS/BAS scales in Dutch adolescents and their mothers. J Pers Assess. 2011;93(5):500–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2011.595745.

Campbell-Sills L, Liverant GI, Brown TA. Psychometric evaluation of the behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation scales in a large sample of outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(3):244–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.244.

Che Q, Yang P, Gao H, Liu M, Zhang J, Cai T. Application of the Chinese Version of the BIS/BAS Scales in Participants With a Substance Use Disorder: An Analysis of Psychometric Properties and Comparison With Community Residents. Front Psychol. 2020;11. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00912.

Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46(2):137–55. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041.

Mohd khatib N azza. Selecting appropriate happiness measures and malleability: a review. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci. 2017;7. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i11/3547.

Carleton RN, Norton MAPJ, Asmundson GJG. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(1):105–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014.

Park LS, Burton CL, Dupuis A, et al. The Toronto Obsessive-compulsive scale: psychometrics of a Dimensional measure of obsessive-compulsive traits. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):310–318e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.008.

Lambe LJ, Burton CL, Anagnostou E, et al. Clinical validation of the parent-report Toronto obsessive–compulsive scale (TOCS): a pediatric open‐source rating scale. JCPP Adv. 2021;1(4):e12056. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12056.

Abramovitch A, Abramowitz JS, McKay D, et al. An ultra-brief screening scale for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: the OCI-CV-5. J Affect Disord. 2022;312:208–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.009.

Burton CL, Wright L, Shan J, et al. SWAN scale for ADHD trait-based genetic research: a validity and polygenic risk study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(9):988–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13032.

Lai KYC, Leung PWL, Luk ESL, Wong ASY, Law LSC, Ho KKY. Validation of the Chinese strengths and weaknesses of ADHD-symptoms and normal-behaviors questionnaire in Hong Kong. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(3):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711430711.

Swanson JM, Schuck S, Porter MM, et al. Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: history of the SNAP and the SWAN Rating scales. Int J Educ Psychol Assess. 2012;10(1):51–70.

Lakes KD, Swanson JM, Riggs M. The reliability and validity of the English and Spanish strengths and weaknesses of ADHD and normal behavior rating scales in a preschool sample: continuum measures of hyperactivity and inattention. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(6):510–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711413550.

Arnett AB, Pennington BF, Friend A, et al. The SWAN captures variance at the negative and positive ends of the ADHD symptom dimension. J Atten Disord. 2013;17(2):152–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054711427399.

Eriksen CW. The flankers task and response competition: a useful tool for investigating a variety of cognitive problems. Vis Cogn. 1995;2(2–3):101–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13506289508401726.

Taylor RL, Cooper SR, Jackson JJ, Barch DM. Assessment of Neighborhood Poverty, cognitive function, and Prefrontal and hippocampal volumes in children. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2023774. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23774.

Ambrosi S, Śmigasiewicz K, Burle B, Blaye A. The dynamics of interference control across childhood and adolescence: distribution analyses in three conflict tasks and ten age groups. Dev Psychol. 2020;56(12):2262–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001122.

Erb CD, Touron DR, Marcovitch S. Tracking the dynamics of global and competitive inhibition in early and late adulthood: evidence from the flanker task. Psychol Aging. 2020;35(5):729–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000435.

Smith AR, White LK, Leibenluft E, et al. The heterogeneity of anxious phenotypes: neural responses to errors in treatment-seeking anxious and behaviorally inhibited youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(6):759–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.05.014.

Meyer A, Nelson B, Perlman G, Klein DN, Kotov R. A neural biomarker, the error-related negativity, predicts the first onset of generalized anxiety disorder in a large sample of adolescent females. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(11):1162–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12922.

Speed BC, Jackson F, Nelson BD, Infantolino ZP, Hajcak G. Unpredictability increases the error-related negativity in children and adolescents. Brain Cogn. 2017;119:25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2017.09.006.

McDermott JM, Pérez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Variations of the flanker paradigm: assessing selective attention in young children. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(1):62–70. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03192844.

Lejuez CW, Aklin W, Daughters S, Zvolensky M, Kahler C, Gwadz M. Reliability and validity of the youth version of the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART-Y) in the assessment of risk-taking behavior among inner-city adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol off J Soc Clin Child Adolesc Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 53. 2007;36(1):106–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410709336573.

Schonberg T, Fox CR, Poldrack RA. Mind the gap: bridging economic and naturalistic risk-taking with cognitive neuroscience. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(1):11–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.10.002.

Peris TS, Galván A. Brain and behavior correlates of risk taking in Pediatric anxiety disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89(7):707–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.11.003.

Bell MD, Imal AE, Pittman B, ** G, Wexler BE. The development of adaptive risk taking and the role of executive functions in a large sample of school-age boys and girls. Trends Neurosci Educ. 2019;17:100120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2019.100120.

Tieskens JM, Buil JM, Koot S, Krabbendam L, van Lier PAC. Elementary school children’s associations of antisocial behaviour with risk-taking across 7–11 years. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(10):1052–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12943.

Koscielniak M, Rydzewska K, Sedek G. Effects of Age and Initial Risk Perception on Balloon Analog Risk Task: The Mediating Role of Processing Speed and Need for Cognitive Closure. Front Psychol. 2016;7. Accessed July 27, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00659.

Braams BR, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, Peper JS, Crone EA. Longitudinal changes in adolescent Risk-Taking: a comprehensive study of neural responses to rewards, Pubertal Development, and risk-taking behavior. J Neurosci. 2015;35(18):7226–38. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4764-14.2015.

Lejuez CW, Read JP, Kahler CW, et al. Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). J Exp Psychol Appl. 2002;8(2):75–84. https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-898x.8.2.75.

Slattery MJ, Grieve AJ, Ames ME, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Neurocognitive function and state cognitive stress appraisal predict cortisol reactivity to an acute psychosocial stressor in adolescents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(8):1318–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.11.017.

Rylander-Rudqvist T, Håkansson N, Tybring G, Wolk A. Quality and quantity of saliva DNA obtained from the self-administrated oragene method–a pilot study on the cohort of Swedish men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2006;15(9):1742–5. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0706.

Looi ML, Zakaria H, Osman J, Jamal R. Quantity and quality assessment of DNA extracted from saliva and blood. Clin Lab. 2012;58(3–4):307–12.

O’Connor K, Bagnell A, McGrath P, et al. An internet-based cognitive behavioral program for adolescents with anxiety: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(7):e13356. https://doi.org/10.2196/13356.

O’Connor KA, Bagnell A, Rosychuk RJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral program on anxiety symptoms in a community-based sample of adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2022;92:102637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102637.

Lam M, Awasthi S, Watson HJ, et al. RICOPILI: Rapid Imputation for COnsortias PIpeLIne. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2020;36(3):930–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz633.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a Tool Set for whole-genome Association and Population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–75.

Atkinson EG, Maihofer AX, Kanai M, et al. Tractor uses local ancestry to enable the inclusion of admixed individuals in GWAS and to boost power. Nat Genet. 2021;53(2):195–204. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-020-00766-y.

Gao F, Chang D, Biddanda A, et al. XWAS: a Software Toolset for Genetic Data Analysis and Association Studies of the X chromosome. J Hered. 2015;106(5):666–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esv059.

Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55(4):997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x.

Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, et al. LD score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):291–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3211.

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006.

de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS Data. PLOS Comput Biol. 2015;11(4):e1004219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219.

Finucane HK, Bulik-Sullivan B, Gusev A, et al. Partitioning heritability by functional annotation using genome-wide association summary statistics. Nat Genet. 2015;47(11):1228–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3404.

Skene NG, Bryois J, Bakken TE, et al. Genetic identification of brain cell types underlying schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2018;50(6):825–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0129-5.

Zeisel A, Hochgerner H, Lönnerberg P, et al. Molecular Architecture of the mouse nervous system. Cell. 2018;174(4):999–1014e22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.021.

Saunders A, Macosko EZ, Wysoker A, et al. Molecular diversity and specializations among the cells of the adult mouse brain. Cell. 2018;174(4):1015–1030e16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.028.

Habib N, Avraham-Davidi I, Basu A, et al. Massively parallel single-nucleus RNA-seq with DroNc-seq. Nat Methods. 2017;14(10):955–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4407.

Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48(3):245–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3506.

Gandal MJ, Zhang P, Hadjimichael E, et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018;362(6420):eaat8127. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8127.

Zhang W, Voloudakis G, Rajagopal VM, et al. Integrative transcriptome imputation reveals tissue-specific and shared biological mechanisms mediating susceptibility to complex traits. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3834. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11874-7.

Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518(7539):317–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14248.

Verhulst B, Maes HH, Neale MC. GW-SEM: A Statistical Package to Conduct genome-wide structural equation modeling. Behav Genet. 2017;47(3):345–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-017-9842-6.

Pritikin JN, Neale MC, Prom-Wormley EC, Clark SL, Verhulst B, Multivariate GWAS. Behav Genet. 2021;51(3):343–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-021-10043-1.

Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2010;26(17):2190–1. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340.

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011.

Wang D, Liu S, Warrell J, et al. Comprehensive functional genomic resource and integrative model for the human brain. Science. 2018;362(6420):eaat8464. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8464.

Byrne EM, Zhu Z, Qi T, et al. Conditional GWAS analysis to identify disorder-specific SNPs for psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(6):2070–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0705-9.

Peyrot WJ, Price AL. Identifying loci with different allele frequencies among cases of eight psychiatric disorders using CC-GWAS. Nat Genet. 2021;53(4):445–54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00787-1.

Lloyd-Jones LR, Zeng J, Sidorenko J, et al. Improved polygenic prediction by bayesian multiple regression on summary statistics. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5086. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12653-0.

Privé F, Arbel J, Vilhjálmsson BJ. LDpred2: better, faster, stronger. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(22–23):5424–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1029.

Choi SW, O’Reilly PF. PRSice-2: polygenic risk score software for biobank-scale data. GigaScience. 2019;8(7):giz082. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giz082.

Yuan J, **ng H, Lamy AL, Consortium TSWG, of the T, Pe’er I. Leveraging correlations between variants in polygenic risk scores to detect heterogeneity in GWAS cohorts. PLOS Genet. 2020;16(9):e1009015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1009015.

Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. Loos R, ed. eLife. 2018;7:e34408. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.34408.

Verbanck M, Chen CY, Neale B, Do R. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50(5):693–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7.

Pain O, Hodgson K, Trubetskoy V, et al. Identifying the common genetic basis of antidepressant response. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2021;2(2):115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.07.008.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant number CIHR: PJT-180339.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC, MM, NS, PA, SES, and SM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work as Primary Investigators. LM, MM, and SM prepared the manuscript. All authors drafted the work and substantially revised it and all authors gave approval of the submitted version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol has been approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (#REB22-1687), the Dalhousie University Research Ethics Board (#2022–6098), the Hospital for Sick Children Research Ethics Board (#1000062807), the University of British Columbia Children and Women’s Research Ethics Board (#H22-02253) and the Hamilton Health Sciences & St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton, Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#15292). Recruitment began at the first site in May 2023 and will continue at all sites until 2027. All participants will provide written informed consent, or assent with parental consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

McAusland, L., Burton, C.L., Bagnell, A. et al. The genetic architecture of youth anxiety: a study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 24, 159 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05583-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05583-9