Abstract

Objective

To identify CT features and establish a nomogram, compared with a machine learning-based model for distinguishing gastrointestinal heterotopic pancreas (HP) from gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).

Materials and methods

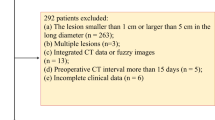

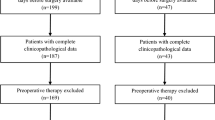

This retrospective study included 148 patients with pathologically confirmed HP (n = 48) and GIST (n = 100) in the stomach or small intestine that were less than 3 cm in size. Clinical information and CT characteristics were collected. A nomogram on account of lasso regression and multivariate logistic regression, and a RandomForest (RF) model based on significant variables in univariate analyses were established. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, mean area under the curve (AUC), calibration curve and decision curve analysis (DCA) were carried out to evaluate and compare the diagnostic ability of models.

Results

The nomogram identified five CT features as independent predictors of HP diagnosis: age, location, LD/SD ratio, duct-like structure, and HU lesion/pancreas A. Five features were included in RF model and ranked according to their relevance to the differential diagnosis: LD/SD ratio, HU lesion/pancreas A, location, peritumoral hypodensity line and age. The nomogram and RF model yielded AUC of 0.951 (95% CI: 0.842–0.993) and 0.894 (95% CI: 0.766–0.966), respectively. The DeLong test found no statistically significant difference in diagnostic performance (p > 0.05), but DCA revealed that the nomogram surpassed the RF model in clinical usefulness.

Conclusion

Two diagnostic prediction models based on a nomogram as well as RF method were reliable and easy-to-use for distinguishing between HP and GIST, which might also assist treatment planning.

Keypoints:

A nomogram and RandomForest model based on CT images were established for differentiating gastrointestinal heterotopic pancreas from small (≤ 3 cm) GIST.

Age, location, LD/SD ratio, HU lesion/pancreas A and duct-like structure (or peritumoral hypodensity line) were identified as independent predictors of gastrointestinal HP in the models.

Two models both had excellent discriminative performance, despite the nomogram may result in a larger net benefit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heterotopic pancreas (HP), also known as “ectopic pancreas”, is defined as pancreatic tissue lacking anatomic or vascular continuity with the main body of the gland [1, 2]. Although HPs can be up to 5.0 cm in size, almost 80% lesions are smaller than 3 cm [3,4,5,6]. They were often incidentally found on the upper gastrointestinal system, specifically the stomach, duodenum, and proximal jejunum in around 0.5–13.7% of corpses or 0.2–0.9% of abdominal surgeries [3, 4, 7]. In fact, the true prevalence of HP is difficult to assess as most patients are asymptomatic [8]. Invasive operations for a confirmative diagnosis as well as surgery are generally not recommended [9, 10]. But some larger lesions, or lesions in specific locations (e.g., duodenum papilla), could cause complications similar to those of the normal pancreas such as pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts and even malignancy, or symptoms such as abdominal pain, bleeding and obstruction [1, 8, 11]. Additionally, malignant transformation of HP is extremely rare, and there are only sporadic case reports available in the literature [1, 12, 13].

Since HP more often manifests as a gastrointestinal submucosal lesion, it might be empirically misdiagnosed as gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (GIST), the true and most common submucosal tumor [14, 15]. Unlike HP, the biological behavior of GIST is complex and demonstrates varying malignant potential, including recurrences and metastasis [16,17,18]. Surgery for GISTs was more focused on the risk class rather than just the size or location of the entities [18, 19], and patients often choose regular follow-up visits or surgeries.

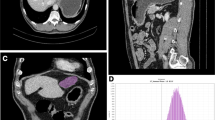

In terms of radiologic appearance, gastrointestinal HP and GIST have many overlap** features, and smaller lesions are harder to identify [2, 20]. Computed tomography (CT), as a non-invasive and common imaging examination method, has been emphasized for preoperative diagnosis of HP lesions and differentiation it from GIST [2, 4, 9, 11, 20,21,22,23]. Furthermore, the application of artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in radiological imaging has been progressively investigated so far [24,25,20] removed the complete cystic HPs, in fact there were also 2 cases of cystic GIST in our study, and no statistical differences was found in image type between the two lesions finally. Other CT features, including ill-defined border, microlobulated appearance [30], presence of low intralesional attenuation and enhancement pattern [22, 30], were also associated with lobular architecture or dilated residual duct of HP [2, 4, 6], and were deduced by prior studies to be distinctive signs of HP. Yet they had not statistically significant difference or were just relevant predictors in our series. Due to HP likely extending to the muscularis propria or the entire wall of gastrointestinal tract [31, 35], we propose “peritumoral hypodensity line” to describe the relationship between the lesion and the peripheral gastrointestinal wall, which could reveal lesions as clear submucosal lesions or represented fat space between the extraluminal lesion and serosal layer (Fig. 2D). It was included in the RF model finally.

Duct-like structure was found to be a significant CT feature with secondary importance in the nomogram, which was referred to a central umbilication located at the mucosa of the lesion, corresponding to the rudimentary duct of the HP as seen in histologic specimens [30, 34]. T2-weighted MR images and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic (MRCP) (Fig. 3B) images are best for confirming a dilated duct in HP, which is also referred to as the “ectopic duct” sign [4, 8, 11]. This sign was not included in the RF model. We infer that this sign, while unique to the ectopic pancreas, was relatively difficult to be observed. Only 7 of 48 HPs were detected this CT morphologic feature in this study, with 2 located in the lower part of stomach, 3 in the duodenum, and 2 in the jejunum or ileum, respectively. We inferred from this that the sign was easier to discern in the small intestine, similar to some previous reports [5, 30]. In addition, the trend in the age distribution of HP and GIST is consistent with most of the studies we’ve seen.

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design may have introduced inherent selection bias, although our patients were enrolled from two institutions. Second, due to the long period of follow-up, different CT machines and protocols were used, which might influence the quantitative analysis. Third, due to the use of lesions LD less than 3 cm in the inclusion criterion, we excluded a great proportion of GISTs. Fourth, the size of our study population was small, especially for HP, and thus the stability of the model may be affected and the false-positive rates may increase.

Conclusion

In brief, two convenient and efficient models based on CT signs was established using nomogram and machine learning method, and could be valuable for discriminating gastrointestinal HP from GIST in clinical practice. Both models have excellent diagnostic prediction performance, although prospective studies with larger sample sizes will be required to confirm these results.

Data Availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HP:

-

heterotopic pancreas

- GIST:

-

gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- HU:

-

Hounsfield unit

- LD:

-

long diameter

- SD:

-

short diameter

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- ROC:

-

the receiver operating characteristic curve

- AUC:

-

the area under the curve

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis

References

Cho JS, Shin KS, Kwon ST, Kim JW, Song CJ, Noh SM, et al. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: ct findings. Radiology. 2000;217:139–44.

Kim JY, Lee JM, Kim KW, Park HS, Choi JY, Kim SH, et al. Ectopic pancreas: ct findings with emphasis on differentiation from small gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Radiology. 2009;252:92–100.

Mortelé KJ, Rocha TC, Streeter JL, Taylor AJ. Multimodality imaging of pancreatic and biliary congenital anomalies. Radiographics: A Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America Inc. 2006;26:715–31.

Rezvani M, Menias C, Sandrasegaran K, Olpin JD, Elsayes KM, Shaaban AM. Heterotopic pancreas: histopathologic features, imaging findings, and complications. Radiographics: A Review Publication of the Radiological Society of North America Inc. 2017;37:484–99.

Park SH, Han JK, Choi BI, Kim M, Kim YI, Yeon KM, et al. Heterotopic pancreas of the stomach: ct findings correlated with pathologic findings in six patients. Abdom Imaging. 2000;25:119–23.

Wei R, Wang QB, Chen QH, Liu JS, Zhang B. Upper gastrointestinal tract heterotopic pancreas: findings from ct and endoscopic imaging with histopathologic correlation. Clin Imaging. 2011;35:353–9.

Christodoulidis G, Zacharoulis D, Barbanis S, Katsogridakis E, Hatzitheofilou K. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6098–100.

Kung JW, Brown A, Kruskal JB, Goldsmith JD, Pedrosa I. Heterotopic pancreas: typical and atypical imaging findings. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:403–7.

Lin YM, Chiu NC, Li AF, Liu CA, Chou YH, Chiou YY. Unusual gastric tumors and tumor-like lesions: Radiological with pathological correlation and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2493–504.

Filip R, Walczak E, Huk J, Radzki RP, Bieńko M. Heterotopic pancreatic tissue in the gastric cardia: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16779–81.

Yang CW, Che F, Liu XJ, Yin Y, Zhang B, Song B. Insight into gastrointestinal heterotopic pancreas: imaging evaluation and differential diagnosis. Insights into Imaging. 2021;12:144.

Ura H, Denno R, Hirata K, Saeki A, Hirata K, Natori H. Carcinoma arising from ectopic pancreas in the stomach: endosonographic detection of malignant change. J Clin Ultrasound: JCU. 1998;26:265–8.

Ulrych J, Fryba V, Skalova H, Krska Z, Krechler T, Zogala D. Premalignant and malignant lesions of the heterotopic pancreas in the esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Liver Diseases: JGLD. 2015;24:235–9.

Nishida T, Blay JY, Hirota S, Kitagawa Y, Kang YK. The standard diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on guidelines. Gastric cancer: Official Journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2016;19:3–14.

Akahoshi K, Oya M, Koga T, Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:2806–17.

Tran T, Davila JA, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an analysis of 1,458 cases from 1992 to 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:162–8.

D’Ambrosio L, Palesandro E, Boccone P, Tolomeo F, Miano S, Galizia D, et al. Impact of a risk-based follow-up in patients affected by gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Eur J cancer (Oxford England: 1990). 2017;78:122–32.

Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimäki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:265–74.

von Mehren M, Kane JM, Riedel RF, Sicklick JK, Pollack SM, Agulnik M, et al. Nccn guidelines® insights: gastrointestinal stromal tumors, version 2.2022. J Natl Compr Cancer Network: JNCCN. 2022;20:1204–14.

Li LM, Feng LY, Chen XH, Liang P, Li J, Gao JB. Gastric heterotopic pancreas and stromal tumors smaller than 3 cm in diameter: clinical and computed tomography findings. Cancer Imaging: The Official Publication of the International Cancer Imaging Society. 2018;18:26.

Liu C, Yang F, Zhang W, Ao W, An Y, Zhang C, et al. Ct differentiation of gastric ectopic pancreas from gastric stromal tumor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:52.

Kim DH, Kim JH, Han S, Kang HJ, Kim SH. Differentiation between small (< 4.5 cm) true subepithelial tumors and ectopic pancreas in the small bowel on computed tomography enterography. Eur Radiol. 2022;32:1760–9.

Yang CW, Liu XJ, Wei Y, Wan S, Ye Z, Yao S, et al. Use of computed tomography for distinguishing heterotopic pancreas from gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Abdom Radiol (New York). 2021;46:168–78.

Jiang Y, Zhang Z, Yuan Q, Wang W, Wang H, Li T, et al. Predicting peritoneal recurrence and disease-free survival from ct images in gastric cancer with multitask deep learning: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4:e340–50.

Hirai K, Kuwahara T, Furukawa K, Kakushima N, Furune S, Yamamoto H, et al. Artificial intelligence-based diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions on endoscopic ultrasonography images. Gastric cancer: Official Journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2022;25:382–91.

Jiang Y, Liang X, Han Z, Wang W, ** S, Li T, et al. Radiographical assessment of tumour stroma and treatment outcomes using deep learning: a retrospective, multicohort study. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3:e371–82.

Brancatelli G, Federle MP, Grazioli L, Blachar A, Peterson MS, Thaete L. Focal nodular hyperplasia: ct findings with emphasis on multiphasic helical ct in 78 patients. Radiology. 2001;219:61–8.

Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd english edition. Gastric cancer: official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. 2011;14:101–112.

Kilman WJ, Berk RN. The spectrum of radiographic features of aberrant pancreatic rests involving the stomach. Radiology. 1977;123:291–6.

Kim DW, Kim JH, Park SH, Lee JS, Hong SM, Kim M, et al. Heterotopic pancreas of the jejunum: Associations between ct and pathology features. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:38–45.

Zhang Y, Sun X, Gold JS, Sun Q, Lv Y, Li Q, et al. Heterotopic pancreas: a clinicopathological study of 184 cases from a single high-volume medical center in china. Hum Pathol. 2016;55:135–42.

Mack T, Lowry D, Carbone P, Barbick B, Kindelan J, Marks R. Multimodality imaging evaluation of an uncommon entity: esophageal heterotopic pancreas. Case Rep Radiol. 2014;2014:614347.

Borghei P, Sokhandon F, Shirkhoda A, Morgan DE. Anomalies, anatomic variants, and sources of diagnostic pitfalls in pancreatic imaging. Radiology. 2013;266:28–36.

Jang KM, Kim SH, Park HJ, Lim S, Kang TW, Lee SJ, et al. Ectopic pancreas in upper gastrointestinal tract: mri findings with emphasis on differentiation from submucosal tumor. Acta Radiol (Stockholm Sweden: 1987). 2013;54:1107–16.

Polkowski M, Butruk E. Submucosal lesions. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin. 2005;15:33–54.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NF, collected and processed data, and drafted the manuscript; HYC, collected data, participated in its design and manuscript editing; XJW, YFL, and JPZ helped in the analysis of image features; QMZ, XBW, and JNY guided the data analysis data processing; JXX and RSY, conceived of the study and contributed to the supervision of the whole process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine because of the retrospective nature of the study. Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analysis used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient agreed to treatment by written consent. The study is approved by the institutional review board of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, N., Chen, HY., Wang, XJ. et al. A CT-based nomogram established for differentiating gastrointestinal heterotopic pancreas from gastrointestinal stromal tumor: compared with a machine-learning model. BMC Med Imaging 23, 131 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-023-01094-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-023-01094-3