Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether liver transplantation is associated with an increased incidence of post-transplant head and neck cancer. This comprehensive meta-analysis evaluated the association between liver transplantation and the risk of head and neck cancer using data from all available studies.

Methods

PubMed and Web of Science were systematically searched to identify all relevant publications up to March 2014. Standardized incidence ratio (SIR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of head and neck cancer in liver transplant recipients were calculated. Tests for heterogeneity, sensitivity, and publishing bias were also performed.

Result

Of the 964 identified articles, 10 were deemed eligible. These studies included data on 56,507 patients with a total follow-up of 129,448.9 patient-years. SIR for head and neck cancer was 3.836-fold higher (95% CI 2.754–4.918, P = 0.000) in liver transplant recipients than in the general population. No heterogeneity or publication bias was observed. Sensitivity analysis indicated that omission of any of the studies resulted in an SIR for head and neck cancer between 3.488 (95% CI: 2.379–4.598) and 4.306 (95% CI: 3.020–5.592).

Conclusions

Liver transplant recipients are at higher risk of develo** head and neck cancer than the general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Liver transplantation is regarded as the therapeutic option of choice in patients with acute and chronic liver disease or liver failure [1]. Long-term outcomes can be enhanced when graft rejection is successfully controlled using immunosuppressive regimens [2, 3]. However, long-term immunosuppression can impair immune function [4], increasing the risk of develo** de novo malignancies after organ transplantation [5]. The most common of these new malignancies are lymphomas, followed by skin malignancies, cervical carcinoma, renal cancer, vulvar carcinoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma [6–8].

Despite the rarity of head and neck cancers in the general population [6], approximately half of all post-transplant malignancies have been found in sites in the head and neck [4]. The association of between liver transplantation and the risk of develo** head and neck cancer has been explored in several populations [9]. Large retrospective trials have found that the incidence of head and neck cancer in liver transplantation recipients ranged from 0.1–2% [10, 11], and that these tumors occurred as early as 34 months after liver transplantation [12–16]. Because of differences in study design, sample selection, sample size, and follow-up period, the association between liver transplantation and head and neck cancer remains unclear. This meta-analysis, which included all relevant studies on head and neck cancer and liver transplantation, was therefore performed to clarify whether the total standardized incidence rate (SIR) of head and neck cancer is higher following liver transplantation than in the general population.

Methods

Publication search

A systematic, comprehensive literature search was carried out using the PubMed and Web of Science databases, to identify all articles investigating the risk of head and neck cancer in liver transplant recipients (last search updated on 31 March, 2014). Search keywords, both free text and medical subject headings (MeSH), included ‘liver transplantation’, ‘organ transplantation’, and ‘head and neck cancer’. The search was limited to studies published in English and to those including only human subjects. Abstracts and unpublished reports were not considered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were selected for meta-analysis if: (a) they were population-based cohort studies in liver transplant recipients; (b) SIR with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated in transplant recipients relative to the general population; (c) they included sufficient data on the incidence, SIR or relative risk (RR) of head and neck cancer, or sufficient numbers of patients; (d) and if they assessed patients with head and neck cancer (ICD: C00-14, C30-32), defined as cancer of the lips, oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, nose and ear. Studies were excluded if: (a) they were case-control studies, case series, or case reports; (b) they lacked sufficient data for meta-analysis; (c) they assessed head and neck cancer following transplantation of organs other than the liver; or (d) they assessed cancers other than head and neck cancer following liver transplantation.

Data extraction

The data from all qualified and adaptive publications were independently extracted by two investigators (QL and LY) using the inclusion criteria mentioned above; any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Characteristics extracted from each study included the first author’s family name, year of publication, type of transplant, data source, the country of participants, number of patients, number of liver transplant cases, number of all cancers, length of follow-up time, mean follow-up time (years), patient-years (years), mean age at transplantation (years), median time to development of any type of cancer (months), number of expected cases of head and neck cancer, number of identified cases of head and neck cancer, and the SIRs of commonly known cancers and head and neck cancer.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA software (version 11; STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas). The unadjusted RR, along with the 95% CI, in each study was employed to assess the strength of head and neck cancer risks in liver transplant recipients relative to the general population.

Heterogeneity among studies, defined as differences in study outcomes, were assessed using a chi-squared-based Q-statistics test. The models of analysis for the pooled RRs were based on the P value. A P value for the Q-statistic greater than 0.05 indicated a lack of heterogeneity among studies, allowing the use of a fixed-effects model (the Mantel–Haenszel method). Otherwise, a random-effects model (the DerSimonian and Laird method) was applied. I 2 was defined as the proportion of total variation resulting from heterogeneity among studies, as opposed to random error or chance, with I 2< 25%, 25–75% and >75% representing low, moderate and high degrees of inconsistency, respectively [17, 18].

One-way sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the effects of individual study data on the pooled RR. Each included study was removed from the pool and the remaining studies re-analyzed to estimate the stability of the results. Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to analyze publication bias. Funnel plot asymmetry was assessed using Egger’s linear regression method on the natural logarithm scale of the RR. A symmetric plot suggested publication bias, with a P value <0.05 indicating significant publication bias.

Results

Characteristics of the eligible studies assessed by meta-analysis

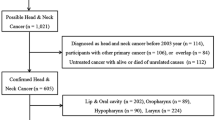

The initial search identified 964 related articles. Application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in the retrieval of 10 eligible publications. These 10 articles, which included 13,853 liver transplants in 56,507 patients, evaluated whether the total SIR for head and neck cancer was higher in liver transplant recipients than in the general population [19–29]. An outline of the literature search and selection process is shown in Figure 1, and the key characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1. These eligible studies were based on patients in several countries, including Finland, Italy, the UK, the Netherlands, Spain, Canada, Sweden and Japan.

Table 2 shows a summary of the interrelated studies with their demographic details. Of the 545 liver transplant recipients who developed cancers and hematological malignancies, 78 developed head and neck cancer, as compared with 10 expected cases. Mean age at transplantation was 48.83 years (range: 43.00–56.05 years) and median time to develop any type of cancer was 50.1 months (range: 38.4–61.0 months), with a mean follow-up time of 7.3 years (range: 5.1–16.0 years) and a total of 129,448.9 patient-years.

Evidence synthesis

Calculation of the overall SIR of the 10 articles in our meta-analysis showed that the risk of head and neck cancer was significantly higher in liver transplant recipients than in the general population (SIR = 3.836, 95% CI: 2.754 – 4.918; P = 0.000; Table 3). Three of these studies calculated SIRs for cancers at different sites in the head and neck, including the pharynx, oral cavity and lip [27]; oral cavity and lip [23]; and larynx, pharynx, oral cavity, lip, nose and middle ear [21]. Figure 2 shows forest plots for individual and overall RR measures. There was no heterogeneity (I 2 = 26.2%, Pheterogeneity =0.203) in the pooled analysis.

Table 4 shows that the risks of cancers other than head and neck cancer, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), Hodgkin lymphoma, non-melanoma, kidney, lung, esophagus and Kaposi’s sarcoma were also significantly increased in liver transplant recipients.

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis assessed the influence of an individual study on the pooled RR by omitting one study and re-analyzing the results. In assessing the association of liver transplantation with the risk of head and neck cancer risk, we found that no individual study altered the overall significance of the RRs, suggesting the stability and reliability of the overall results (Figure 3). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the omission of any one study resulted in SIRs between 3.488 (95% CI: 2.379–4.598) and 4.306 (95% CI: 3.020–5.592; Table 5).

Publication bias

Potential publication bias of the literature was assessed using Funnel plots and Begg’s and Egger’s tests. Funnel plot asymmetry was not observed. Publication bias was not evident (t = -1.72, P = 0.124) (Figure 4).

Discussion

Liver transplant recipients may have increased risk for develo** de novo cancers [30], with most of these cancers appearing about 6 years after transplantation [3]. Tumors such as NHL and Kaposi’s sarcoma, which are rare in the general population, are encountered more frequently in transplant recipients. Head and neck cancer, which accounts for <4% of malignancies in the general population, accounts for about 15% of malignancies in transplant recipients [4, 31]. This meta-analysis was performed to clarify the relationship between head and neck cancer and liver transplantation, finding that transplant recipients were at significantly greater risk of head and neck cancer than the general population (SIR = 3.836, 95% CI 2.754–4.918, P = 0.000). Thus, these results provide further evidence that organ transplant recipients may be at increased risk of head and neck cancer compared with the general population.

The exact mechanism associated with the increased incidence of de novo head and neck cancer in liver transplantation recipients is unknown. Long-term administration of immunosuppressive agents may be responsible, as reported for other malignancies [4, 32, 33]. These immunosuppressive agents may depress immune surveillance and permit tumor development [29, 34]. Indeed, immunosuppression resulting from genetic defects, AIDS or drugs, has been associated with a higher risk of malignancy than in an immunocompetent population [35]. Anti-rejection reagents, such as azathioprine, CyA and tacrolimus, may favor the establishment of a de novo malignancy by initiating and/or potentiating DNA damage [36]. Alternatively, these agents may induce phenotypic changes in cells including nontransformed cells, increasing membrane ruffling, cell locomotion, and extracellular matrix-independent growth mediated by transforming-growth-factor [37]. Tacrolimus, which is a more potent immunosuppressive agent than CyA, showed a dose-dependent relationship with de novo malignancy [38]. Alcohol intake, which has been associated with tumor development in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis and after liver transplantation, may also be responsible [22]. Alcoholic liver cirrhosis is a common chronic liver disease and an indication for liver transplantation [39]. The incidence of de novo malignancies was found to be significantly higher in patients who underwent liver transplantation for alcoholic than for non-alcoholic cirrhosis [40]. Alcohol consumption is also an established risk factor for head and neck cancers [41]. Interestingly, oropharyngeal carcinoma was observed only in patients who underwent liver transplantation for alcoholic liver cirrhosis [42]. However, the articles included in our meta-analysis did not include data on alcohol consumption in liver transplant recipients, preventing a determination of whether liver transplantation was independently associated with a higher risk of head and neck cancer. Previous studies have also demonstrated the significance of persisting pre-transplantation tobacco abuse on post-transplantation outcomes [43]. In contrast, quitting smoking after liver transplantation might protect against tumor growth owing to the association between tobacco abuse on neoplasia [22]. Disease-free survival was worse in liver transplant patients with head and neck cancer and a history of smoking (active or prior smokers) than in nonsmokers [44]. The association between tobacco abuse and poor health outcomes suggests the need for liver transplant candidates to quit smoking. Interventional and screening programs can help reduce transplant-related tumorigenesis in liver transplant recipients. Several other risk factors are associated with malignancy in liver transplant recipients, including adverse psychosocial factors, poor treatment modality, and premalignant disease [30, 44, 45]. A systematic review has com-prehensively analyzed these risk factors [30].

This study had several limitations: 1) Most of the studies were from western countries, with only one involving patients from an Asian country (Japan). Despite an exhaustive literature search and the absence of publication bias, as shown by the funnel plot and Egger’s test, some non-English publications and unpublished data related to our study may have been omitted, especially those reporting negative findings that could potentially influence the results. It was not possible to evaluate the effect of ethnicity (genetic background) on the association between head and neck cancer and liver transplantation. 2) The liver transplant recipients were not all screened for head and neck cancer before transplantation. Therefore, we could not exclude the possibility that some of these cancers may have been present prior to transplantation. 3) Because our screened studies had patients of different backgrounds, and their methods and sample size varied, some data were missing. Two indices, mean age at diagnosis of malignancy and mean time to develop head and neck cancer, were not measured in the included studies. 4) Detailed information on the type and dosage of immunosuppressive drugs was not available for further subgroup analysis. Low-dose cyclosporine was associated with a lower rate of malignancy than high-dose cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients [46]. Moreover, tacrolimus is more potent than cyclosporine. Different agents may exert different effect on the development of cancers. 5) Transplant recipients may be followed up more regularly here than the general population. However, these findings are not available. Despite these limitations, our study did not show significant heterogeneity or publication bias, indicating that these results were reliable.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis showed that liver transplant recipients were at a higher risk of develo** head and neck cancer than the general population. Liver transplant recipients should therefore be screened intensively for head and neck cancer, which may enhance early diagnosis and treatment, as well as patient outcomes.

References

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: liver transplantation--June 20-23, 1983. Hepatology. 1984, 4 (1 Suppl): 107S-110S.

Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Fraumeni JF, Kasiske BL, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Wolfe RA, Goodrich NP, Bayakly AR, Clarke CA, Copeland G, Finch JL, Fleissner ML, Goodman MT, Kahn A, Koch L, Lynch CF, Madeleine MM, Pawlish K, Rao C, Williams MA, Castenson D, Curry M, Parsons R, Fant G, Lin M: Spectrum of cancer risk among US solid organ transplant recipients. JAMA. 2011, 306 (17): 1891-1901. 10.1001/jama.2011.1592.

Karamchandani D, Arias-Amaya R, Donaldson N, Gilbert J, Schulte KM: Thyroid cancer and renal transplantation: a meta-analysis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010, 17 (1): 159-167. 10.1677/ERC-09-0191.

Rabinovics N, Mizrachi A, Hadar T, Ad-El D, Feinmesser R, Guttman D, Shpitzer T, Bachar G: Cancer of the head and neck region in solid organ transplant recipients. Head Neck. 2014, 36 (2): 181-186. 10.1002/hed.23283.

Grulich AE, Van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM: Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007, 370 (9581): 59-67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61050-2.

Sint Nicolaas J, De Jonge V, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Van Leerdam ME, Veldhuyzen-van Zanten SJ: Risk of colorectal carcinoma in post-liver transplant patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2010, 10 (4): 868-876. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03049.x.

Gourin CG, Terris DJ: Head and neck cancer in transplant recipients. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004, 12 (2): 122-126. 10.1097/00020840-200404000-00012.

Fung JJ, Jain A, Kwak EJ, Kusne S, Dvorchik I, Eghtesad B: De novo malignancies after liver transplantation: a major cause of late death. Liver Transpl. 2001, 7 (11 Suppl 1): S109-S118.

Ramsay HM, Reece SM, Fryer AA, Smith AG, Harden PN: Seven-year prospective study of nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence in U.K. renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007, 84 (3): 437-439. 10.1097/01.tp.0000269707.06060.dc.

Jimenez C, Lumbreras C, Paseiro G, Loinaz C, Romano DR, Andres A, Aguado JM, Morales JM, Del Palacio A, Garcia I, Moreno E: Treatment of mucor infection after liver or pancreas-kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002, 34 (1): 82-83. 10.1016/S0041-1345(01)02676-8.

Frezza EE, Fung JJ, Van Thiel DH: Non-lymphoid cancer after liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997, 44 (16): 1172-1181.

Tallon Aguilar L, Barrera Pulido L, Bernal Bellido C, Pareja Ciuro F, Suarez Artacho G, Alamo Martinez JM, Garcia Gonzalez I, Gomez Bravo MA, Bernardos Rodriguez A: Causes and predisposing factors of de novo tumors in our series of liver transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2009, 41 (6): 2453-2454. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.05.012.

Saigal S, Norris S, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton N, O’Grady J: Evidence of differential risk for posttransplantation malignancy based on pretransplantation cause in patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002, 8 (5): 482-487. 10.1053/jlts.2002.32977.

Sanchez EQ, Marubashi S, Jung G, Levy MF, Goldstein RM, Molmenti EP, Fasola CG, Gonwa TA, Jennings LW, Brooks BK, Klintmalm GB: De novo tumors after liver transplantation: a single-institution experience. Liver Transpl. 2002, 8 (3): 285-291. 10.1053/jlts.2002.29350.

Duvoux C, Delacroix I, Richardet JP, Roudot-Thoraval F, Metreau JM, Fagniez PL, Dhumeaux D, Cherqui D: Increased incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis. Transplantation. 1999, 67 (3): 418-421. 10.1097/00007890-199902150-00014.

Jain AB, Yee LD, Nalesnik MA, Youk A, Marsh G, Reyes J, Zak M, Rakela J, Irish W, Fung JJ: Comparative incidence of de novo nonlymphoid malignancies after liver transplantation under tacrolimus using surveillance epidemiologic end result data. Transplantation. 1998, 66 (9): 1193-1200. 10.1097/00007890-199811150-00014.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003, 327 (7414): 557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002, 21 (11): 1539-1558. 10.1002/sim.1186.

Ettorre GM, Piselli P, Galatioto L, Rendina M, Nudo F, Sforza D, Miglioresi L, Fantola G, Cimaglia C, Vennarecci G, Vizzini GB, Di Leo A, Rossi M, Tisone G, Zamboni F, Santoro R, Agresta A, Puro V, Serraino D: De novo malignancies following liver transplantation: results from a multicentric study in central and southern Italy, 1990-2008. Transplant Proc. 2013, 45 (7): 2729-2732. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.07.050.

Kaneko J, Sugawara Y, Tamura S, Aoki T, Sakamoto Y, Hasegawa K, Yamashiki N, Kokudo N: De novo malignancies after adult-to-adult living-donor liver transplantation with a malignancy surveillance program: comparison with a Japanese population-based study. Transplantation. 2013, 95 (9): 1142-1147. 10.1097/TP.0b013e318288ca83.

Krynitz B, Edgren G, Lindelof B, Baecklund E, Brattstrom C, Wilczek H, Smedby KE: Risk of skin cancer and other malignancies in kidney, liver, heart and lung transplant recipients 1970 to 2008–a Swedish population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2013, 132 (6): 1429-1438. 10.1002/ijc.27765.

Herrero JI, Pardo F, D’Avola D, Alegre F, Rotellar F, Inarrairaegui M, Marti P, Sangro B, Quiroga J: Risk factors of lung, head and neck, esophageal, and kidney and urinary tract carcinomas after liver transplantation: the effect of smoking withdrawal. Liver Transpl. 2011, 17 (4): 402-408. 10.1002/lt.22247.

Collett D, Mumford L, Banner NR, Neuberger J, Watson C: Comparison of the incidence of malignancy in recipients of different types of organ: a UK Registry audit. Am J Transplant. 2010, 10 (8): 1889-1896. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03181.x.

Herrero JI, Alegre F, Quiroga J, Pardo F, Inarrairaegui M, Sangro B, Rotellar F, Montiel C, Prieto J: Usefulness of a program of neoplasia surveillance in liver transplantation. A preliminary report. Clin Transplant. 2009, 23 (4): 532-536. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00927.x.

Baccarani U, Piselli P, Serraino D, Adani GL, Lorenzin D, Gambato M, Buda A, Zanus G, Vitale A, De Paoli A, Cimaglia C, Bresadola V, Toniutto P, Risaliti A, Cillo U, Bresadola F, Burra P: Comparison of de novo tumours after liver transplantation with incidence rates from Italian cancer registries. Dig Liver Dis. 2010, 42 (1): 55-60. 10.1016/j.dld.2009.04.017.

Jiang Y, Villeneuve PJ, Fenton SS, Schaubel DE, Lilly L, Mao Y: Liver transplantation and subsequent risk of cancer: findings from a Canadian cohort study. Liver Transpl. 2008, 14 (11): 1588-1597. 10.1002/lt.21554.

Aberg F, Pukkala E, Hockerstedt K, Sankila R, Isoniemi H: Risk of malignant neoplasms after liver transplantation: a population-based study. Liver Transpl. 2008, 14 (10): 1428-1436. 10.1002/lt.21475.

Serraino D, Piselli P, Busnach G, Burra P, Citterio F, Arbustini E, Baccarani U, De Juli E, Pozzetto U, Bellelli S, Polesel J, Pradier C, Dal Maso L, Angeletti C, Carrieri MP, Rezza G, Franceschi S, Immunosuppression and Cancer Study Group: Risk of cancer following immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients and in HIV-positive individuals in southern Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2007, 43 (14): 2117-2123. 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.015.

Haagsma EB, Hagens VE, Schaapveld M, van den Berg AP, De Vries EG, Klompmaker IJ, Slooff MJ, Jansen PL: Increased cancer risk after liver transplantation: a population-based study. J Hepatol. 2001, 34 (1): 84-91. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)00077-5.

Chak E, Saab S: Risk factors and incidence of de novo malignancy in liver transplant recipients: a systematic review. Liver Int. 2010, 30 (9): 1247-1258. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02303.x.

Winkelhorst JT, Brokelman WJ, Tiggeler RG, Wobbes T: Incidence and clinical course of de-novo malignancies in renal allograft recipients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2001, 27 (4): 409-413. 10.1053/ejso.2001.1119.

Di Benedetto F, Di Sandro S, De Ruvo N, Berretta M, Masetti M, Montalti R, Ballarin R, Cocchi S, Potenza L, Luppi M, Gerunda GE: Kaposi’s sarcoma after liver transplantation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008, 134 (6): 653-658. 10.1007/s00432-007-0329-3.

Dhillon MS, Rai JK, Gunson BK, Olliff S, Olliff J: Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in liver transplantation. Br J Radiol. 2007, 80 (953): 337-346. 10.1259/bjr/63272556.

Sheil AG: Cancer in organ transplant recipients: part of an induced immune deficiency syndrome. Br Med J. 1984, 288 (6418): 659-661. 10.1136/bmj.288.6418.659.

Penn I: Why do immunosuppressed patients develop cancer?. Crit Rev Oncog. 1989, 1 (1): 27-52.

Dalton A, Curtis D, Harrington CI: Synergistic effects of azathioprine and ultraviolet light detected by sister chromatid exchange analysis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1990, 45 (1): 93-99. 10.1016/0165-4608(90)90072-I.

Hojo M, Morimoto T, Maluccio M, Asano T, Morimoto K, Lagman M, Shimbo T, Suthanthiran M: Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature. 1999, 397 (6719): 530-534. 10.1038/17401.

Benlloch S, Berenguer M, Prieto M, Moreno R, San Juan F, Rayon M, Mir J, Segura A, Berenguer J: De novo internal neoplasms after liver transplantation: increased risk and aggressive behavior in recent years?. Am J Transplant. 2004, 4 (4): 596-604. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00380.x.

Jain A, DiMartini A, Kashyap R, Youk A, Rohal S, Fung J: Long-term follow-up after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease under tacrolimus. Transplantation. 2000, 70 (9): 1335-1342. 10.1097/00007890-200011150-00012.

Jimenez C, Rodriguez D, Marques E, Loinaz C, Alonso O, Hernandez-Vallejo G, Marin L, Rodriguez F, Garcia I, Moreno E: De novo tumors after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002, 34 (1): 297-298. 10.1016/S0041-1345(01)02770-1.

La Vecchia C, Zhang ZF, Altieri A: Alcohol and laryngeal cancer: an update. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008, 17 (2): 116-124. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b6fd40.

Vallejo GH, Romero CJ, De Vicente JC: Incidence and risk factors for cancer after liver transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005, 56 (1): 87-99. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.12.011.

DiMartini A, Javed L, Russell S, Dew MA, Fitzgerald MG, Jain A, Fung J: Tobacco use following liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: an underestimated problem. Liver Transpl. 2005, 11 (6): 679-683. 10.1002/lt.20385.

Nelissen C, Lambrecht M, Nevens F, Van Raemdonck D, Vanhaecke J, Kuypers D, Pirenne J, Nuyts S: Noncutaneous head and neck cancer in solid organ transplant patients: single center experience. Oral Oncol. 2014, 50 (4): 263-268. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.016.

Harper RG, Wager J, Chacko RC: Psychosocial factors in noncompliance during liver transplant selection. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010, 17 (1): 71-76. 10.1007/s10880-009-9181-8.

Dantal J, Hourmant M, Cantarovich D, Giral M, Blancho G, Dreno B, Soulillou JP: Effect of long-term immunosuppression in kidney-graft recipients on cancer incidence: randomised comparison of two cyclosporin regimens. Lancet. 1998, 351 (9103): 623-628. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08496-1.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/14/776/prepub

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81172694, No.81473013 and No.81270537), the Outstanding Youth Fund of Jiangsu Province (SBK2014010296), the Research Project of the Chinese Ministry of Education (213015A), the Qinglan Project of Jiangsu Province (JX2161015124), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions. The funders had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or the decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

QL, LY: literature search and data extraction; QL, LY, CX: statistics analysis; AG, ZYJ: study design and data interpretation; QL, LY, CX, AG, PZ, ZYJ: manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Qian Liu, Lifeng Yan, Cheng Xu contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Yan, L., Xu, C. et al. Increased incidence of head and neck cancer in liver transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 14, 776 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-776

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-776