Abstract

The massively accelerated biodiversity loss rate in the Anthropocene calls for an efficient and effective way to identify the spatial and temporal dynamics of endangered species. To this end, we developed a useful identification framework based on a case study of locally endangered Sousa chinensis by combining both LEK (local ecological knowledge) evaluation and regional boat-based survey methods. Our study investigated the basic ecological information of Sousa chinensis in the estuaries of eastern Guangdong that had previously been neglected, which could guide the future study and conservation. Based on the statistical testing of reported spatial and temporal dolphins sighting data from fishermen and the ecological monitoring analyses, including sighting rate, site fidelity and residence time estimations, some of the current Sousa chinensis units are likely to be geographically isolated and critically endangered, which calls for much greater conservation efforts. Given the accelerated population extinction rate and increasing budgetary constraints, our survey pattern can be applied in a timely and economically acceptable manner to the spatial and temporal assessment of other threatened coastal delphinids, particularly when population distributions are on a large scale and traditional sampling methods are difficult to implement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human activities have profoundly affected marine ecosystem via direct and indirect means1,2,3,4. Habitat loss, fragmentation and spatial heterogeneity are increasingly common in the sea, resulting in the division of large, continuous habitats into small and isolated habitat patches, in which ecological processes are altered, contributing significantly (resulting in 37% of reported marine taxa extinctions) to the decline, isolation and loss of wild populations4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Population isolation and fragmentation diminish the connectivity among habitat patches, leading to cascading geographical isolation, the restriction of gene flow and ultimately population extinction11,12,13,14,15. In this context, marine mammals, which can serve as indicators or sentinels of ecosystem health16,17,18,19, are more sensitive to environment stressors than other species and are more likely to undergo population decline and local extinction2,3. Predictive models of extinction risk indicate that approximately 37% of all marine mammals are now at risk of extinction20. Habitat loss and fragmentation are the main (become an increasingly dominant threat over the next 150 years) threats3,4,20. The extinction process leaves different spatial signatures on species’ distribution patterns21,22. It is for the conservation of marine mammals to decipher the evolutionary trend of spatial isolation before extinction occurs because the knowledge of the spatial and temporal patterns of the indicator and umbrella species will allow wildlife and natural resource managers to make better spatial management plans18,19,23,24. Given that coastal dolphins, which are restricted inshore and are seriously affected by escalating anthropogenic activities20,25,26, are the most threatened marine mammal species, we aimed to use a case study of a coastal dolphin species to establish an effective framework to determine temporal and large-scale spatial patterns.

Humpback dolphins (genus Sousa) are small cetaceans that are widely distributed in the eastern Atlantic, Indian and western Pacific Oceans (Fig. 1a)27,28,29,30. As shallow coastal waters inhabitants, they also come into particularly frequent contact with human activity and are influenced by habitat changes31. One paramount issue for conservation is to evaluate the evolutionary divergence and isolation, which helps to identify conservation units. Recent studies have provided a robust and clear picture of the divergence patterns showing that at least four species in genus Sousa, which might be driven by environmental breakdowns, are now on separated evolutionary tracks27,28. Therefore, from the perspective of species-level conservation, a “divide and conquer” strategy is recommended28. However, these four species may share a similar fate as that of other coastal and riverine dolphin species: being exposed to levels of human impact that may threaten local populations26,32. Given population extinctions are a more sensitive indicator of the loss of biological capital than species extinctions33,34, we argue that spatial pattern investigation and regional threat assessment at the conspecific population level are of great necessity.

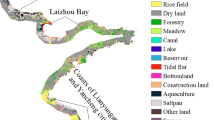

Survey maps.

(a) The global distribution ranges of humpback dolphin (genus Sousa), shown as shaded regions along the coasts; (b) Eastern Guangdong coastline (from XM to PRE) showing the distribution of fishermen interview locations (FI), the color bar and the times under the map, which were derived from the interview data, indicate the possible IPHBD subpopulation temporal changes (the time when the distribution gap occurred); (c) Shantou waters, showing the boat-based survey area (grids area). Inset map underneath is a map of Guangdong and Fujian showing the location of the study area (boxed action). We created the maps with the program ArcMap of ArcGIS [10.2.2] (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis). Map (a) was developed from previously reported global population distribution data of the humpback dolphin27,28,29,30.

The Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins (IPHBD) in China are known as Chinese white dolphins (Sousa chinensis). Historically distributed from the mouth of the Yangtze River to the Vietnam border to the north (Fig. 1a)35, the population decreased as the habitat dwindled and now only five habitation locales are reported31. Previous study indicated that ** to Gangkou town in Fig. 1b) and the proportion of IPHBD sightings of the informants.

Reported sighting proportion tests (RSP tests)

Of the 232 informants, 181 reported that they had seen IPHBDs one or more times. When asked about their perceptions of changes in IPHBD sightings, 95.4% of the informants who responded this question (n = 177) considered that the IPHBD sighting rate in the present was lower than that in the past. The chi-square tests indicated that the proportions of IPHBD sightings by the local fishing communities were differently distributed across the surveyed locations (χ2 = 58.13, df = 11, p < 0.001). Only 31% of the informants in Shenquan Town and 44% informants in Gangkou Town had ever seen IPHBDs (Fig. 2b). After removing some of the responders who encountered IPHBDs in other places (e.g., Hainan, PRE, **, three sites in Nanao of Shantou, three locations in Honghai Bay-Shanwei, Magong and Houmen). The results of the sighting data indicated congruence and no evidence of a significant difference was found (p = 0.374, 0.588 and 0.282).

Temporal distribution of IPHBD last-sighting dates (a) and reported IPHBD group size (b) across the 12 surveyed locations (1–12 are locations from Rao** to Gangkou Town in Fig. 1b; here, 13 represents the locations where the informants saw IPHBDs outside of the study region, such as Hainan, PRE et al.).

Latest sighting and group size tests (LS and GS tests)

The data sets indicated that the distribution of latest IPHBD sighting times also varied across the surveyed locations (Fig. 3a). Rao**, Shantou (Nanao and Haojiang on the map) and Honghai Bay (Shanwei, Magong and Houmen on the map) reported IPHBD sightings in 2013 (Fig. 3). The mean group size of reported IPHBDs in these three locations were 2.8, 3.73 and 1, respectively. In contrast, Shenquan, Zhelang and Gangkou Town had lower sighting proportions and earlier latest-sighting-dates, as well as a smaller IPHBD group size (Fig. 3). The variance analysis showed the significant geographic difference of the latest sighting records (df = 11, F = 9.292, p < 0.001). In the further multiple comparisons by the Scheffe test, the adjacent locations, such as **ghai and Shenquan (p = 0.013), Jiazi and Wukan (p = 0.034) and Houmen and Gangkou Town (p = 0.005), presented significant variations, indicating different temporal change patterns of IPHBD units among the surveyed locations, whereas there were no significant differences found among Rao** and Shantou (p = 0.998) or Shanwei, Magong and Houmen (P = 0.999, 1.0, 0.984). When we tested the distribution and medians of the latest 10-year group size of IPHBD using Kruskal-Wallis test, the results also showed significant spatial differences (p < 0.001). These results indicated that the IPHBD distribution gaps likely occurred in Gangkou Town, Jiazi, Shenquan and **ghai in the 1970 s, 1990 s, 1970 s and 2000 s, respectively (Fig. 3). The spatial and temporal distribution patterns are presented on the map (Fig. 1).

Seasonal preference tests (SP tests)

Although there were different seasonal ratios in each surveyed location (Fig. 4), no evidence of apparent spatial variation was found in the reported IPHBD seasonal investigation by chi-square test (χ2 = 33.184, df = 48, p = 0.949). When we investigated the seasonal bias of all surveyed locations using variance analysis, significant differences were found across the five responses of seasonal questions (df = 4, F = 16.308, p < 0.001). In the post-hoc tests using the Siak method, the fifth answer (most of the year or no seasonal correlation) was significantly more common than other answers (p ≤ 0.001). In contrast, the proportion of reports in the winter season lagged far behind the other seasons (p < 0.05) and no significant variation was found between spring and autumn (p = 1.00). We attributed the lower proportion of winter preference to lower fishermen survey efforts in the winter due to circumstances such as bad weather conditions49.

Vessel-based survey

Photo identification (PI)

Between 2012 and 2014, 69 line-transect vessel surveys were conducted in Shantou waters. A total of 51 schools of IPHBDs were sighted, from which only 19 IPHBDs were catalogued (excluding one calf). The identified animals included 18 adults and 1 spotted juvenile, with the exception of one calf. All of the individuals were photographed on more than four occasions, with two individuals photographed as many as 11 times (Fig. 5a). Overall, the rate of discovery (the cumulative number of identified individuals) reached a plateau before the end of the study period, suggesting that the vast majority of animals in the study area had been captured (Fig. 5b).

Site fidelity (SF)

There were some variations in the sighting rate (mean 0.239 ± SE 0.017) of the 19 marked individuals, excluding calves, upon evaluation using the total photo-identification survey data (Fig. 6a). However, all of these individuals were sighted in more than 10% of surveys with photographs taken (minimum 14%), indicating moderate and high sighting rates. All of the individuals were sighted in more than two seasons (median = 0.5, 5 seasons) and one individual was sighted in 8 of the 10 surveyed seasons (Fig. 6b). Although seasonal sighting rates varied, no significant difference was found using the chi-square method (χ2 = 16.72, df = 18, p = 0.54). Additionally, yearly sighting rates (mean 0.86 ± SE 0.053, sightings per year) indicated that many of the IPHBDs identified were seen in more than two calendar years and no significant variations were found from the overall statistical data (χ2 = 23.85, df = 18, p = 0.16).

Residence time (RT)

Of the four pairs of models applied to the data using SOCPROG50, the “closed population” model curve matched the data best (AIC = 3119.4748, Table 1), although the accuracy of this model’s fit differed little from the emigration/mortality model (ΔAIC = 1.8634) and the emigration/reimmigration model (ΔAIC = 2.316) in comparison to the emigration + reimmigration + mortality model (ΔAIC = 21.7776) (Table 1). All models produced the same graphic display (straight line, Fig. 7a). Estimates of the mean population size and residence times from the closed model indicate that approximately 19 (18.9774 ± SE 0.48358; 95% CI = 18.0826, 19.9128) Chinese white dolphins were ordinarily resident in Shantou waters. The LIR (lagged identification rate) slightly fluctuated in short time lags, with relatively higher standard errors compared to the actual estimates (Fig. 7a), likely indicating that individuals exhibited a variable resighting pattern. However, the LIR remained stable over time, suggesting no influx or outflux. Further, the maximum intervals between the resightings of each IPHBD individual (mean 22.42 ± SE 1.66 month) indicated the long time spent in the study area (Fig. 7b).

Computation of lagged identification rates (dots) for IPHBDs in Shantou waters using SOCPROG50, with vertical lines indicating jackknifed error bars (a) and maximum intervals of individual resighting (b).