Abstract

An ever-increasing demand for novel antimicrobials to treat life-threatening infections caused by the global spread of multidrug-resistant bacterial pathogens stands in stark contrast to the current level of investment in their development, particularly in the fields of natural-product-derived and synthetic small molecules. New agents displaying innovative chemistry and modes of action are desperately needed worldwide to tackle the public health menace posed by antimicrobial resistance. Here, our consortium presents a strategic blueprint to substantially improve our ability to discover and develop new antibiotics. We propose both short-term and long-term solutions to overcome the most urgent limitations in the various sectors of research and funding, aiming to bridge the gap between academic, industrial and political stakeholders, and to unite interdisciplinary expertise in order to efficiently fuel the translational pipeline for the benefit of future generations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This article is conceived as a general roadmap with the central aim of promoting and accelerating translational science in the early stages of novel antibiotic discovery towards lead candidate development. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture, together with inappropriate waste management and environmental transmission, have led to substantially increased antimicrobial resistance (AMR)1,2,3,4,5 and associated bacterial persistence6,7. This is of major public concern, since most areas of modern medicine are inconceivable without access to effective antimicrobial treatment8. It is estimated that at least 700,000 people worldwide die each year as a result of drug-resistant infections, and this could rise to as much as 10 million by 2050 if the problem of AMR is not addressed9,10.

The anticipated death toll caused by drug-resistant infections over the next years and decades may be compared with the global fatality rate of the current SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/), which has already led to multibillion-dollar investments in vaccine development, repurposing existing drugs and antiviral discovery. A perhaps overlooked aspect of concern with the COVID-19 pandemic is the high numbers of secondary infections, often associated with multidrug-resistant bacteria, which are observed especially in hospitalized patients and those with already compromised immune systems11,12. Associated with this problem is the massive use of antibiotics as a COVID-19 (co)treatment worldwide13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, which is predicted to add to the ongoing emergence of AMR25,26,27,28,29. This multiplying effect of COVID-19 on the spread of bacterial resistance will most likely have further negative clinical, economic and societal consequences in the near future30,31.

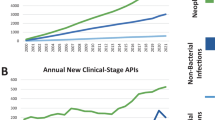

Unfortunately, the dramatic worldwide rise of bacterial pathogens resistant to antibacterial agents32 cannot be counteracted by the current low development pace of therapeutics with new mode(s) of action (MoA(s)). While there are nearly 4,000 immuno-oncology agents in development43,44. In the commercial sector, innovation has, thus, been left to SMEs, which must deal with high attrition associated with the early phases of discovery and optimization39,43,45,46,47,48, and the huge capital risks49,50.

Large funding gaps can be seen in the early stages of hit discovery, as well as during hit and lead optimization, which are associated mainly with academic research and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Indicated figures are representative numbers of typical broad-spectrum antibiotic development programmes leading from several thousands of initial hits to the approval of at least one marketable candidate72,318,319,320,321. *Timings are dependent on a number of factors and can vary greatly. A minimum to maximum range for complete development (discovery to market) is 8–18 years (average 13–14 years). **The cost per molecule/candidate (in million euros, m€) does not include extended costs for attrition (failed programmes) and lost opportunities associated with increased cycle time until reaching the next development phase; such extensions can increase the required budget for the early stages up to 50–100 m€ (refs39,48,322). N (orange diamond), nomination of (pre)clinical candidate(s); PPPs, public–private partnerships; ROI, return on investment.

New economic models for development specifically designed for this area are sorely needed to ensure future advancements51,52,53,54. A recent initiative that supports SMEs in the late-stage development of new antibiotics is the AMR Action Fund, which was launched by more than 20 leading biopharmaceutical companies to push mainly phase II and III trials of advanced candidates55. Unfortunately, the fund does not cater for the early stages of research. In addition, several countries are implementing new pull incentive programmes with different priorities. While the Swedish model aims at securing sustained access to relevant antibiotics that have already been approved56, plans in the UK57,58 as well as in the USA (e.g. PASTEUR59 and DISARM60 acts) strive to stimulate the development of new antibacterial products by using subscription models or delinkage models51. Such initiatives are promising, as they introduce much-needed market entry rewards, but they might fall short on a global scale if they do not include the ‘critical mass’ of the world’s largest economies.

Innovation in the early stages of antibiotic drug discovery can also be driven by the academic sector. However, from the academic perspective, partnering with external funders such as the pharmaceutical industry is, in many cases, only realistic after the nomination of extensively validated preclinical candidates, and often even requires phase I clinical data. Typically, this cannot be achieved by research-driven funding and infrastructure alone. Several global health organizations and public–private partnerships (PPPs), including the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X), Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) and others, started to support, at least partially, the mid-to-late lead optimization through to clinical proof of concept61,62,63, possibly accompanied by stakeholders associated with the Biotech companies in Europe combating AntiMicrobial resistance (BEAM) Alliance or the Replenishing and Enabling the Pipeline for Anti-Infective Resistance (REPAIR) Impact Fund64,65. However, even the growing diversity of such push incentives are, in many cases, insufficient and primarily focused on companies. In addition to these approaches, a strategy is required that helps academic researchers to advance their project portfolio to a level that facilitates early interaction and possibly partnering with pharmaceutical companies in the interest of a successful, cross-sectoral development pipeline66. Hence, creating new incentive models in the field is an essential process that can only be moved forward if the public, academic and industrial sectors join forces39,67,68,69.

In this respect, our position paper provides an overview of the early phases of antibacterial drug discovery, including hit and lead identification, optimization and development to the (pre)clinical stages by summarizing current limitations, relevant approaches and future perspectives, as well as by presenting selected case studies. In terms of a principal guidance for researchers in the field, we suggest possible solutions for a number of obstacles to improve both quality and quantity of antibacterial hits and leads. To strengthen and emphasize these early stages as an absolute necessity for a sustained generation of novel antibiotics, we are recommending a new level of interaction between the various stakeholders and academic disciplines in the area of antibiotic drug research. The strengths and opportunities that small-molecule therapeutics offer can help address antibiotic resistance more successfully during the coming years, in the interests of both patients and investors, provided that the multiplicity of hurdles along the translational path will be overcome (Table 1). Altogether, our aims are in line with the ‘One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance’ introduced by the European Commission70, as well as the WHO programme to fight the rising number of bacterial priority pathogens with steadily growing impact on global public health71.

Synthetic hit compounds

Here, we address the development of profitable strategies to identify and prioritize novel antibacterial hit compounds, with a particular focus on synthetic small molecules. As a foundation, we introduce three main pillars that represent core elements of fruitful hit discovery programmes.

Hit definition, chemical libraries and medicinal chemistry

The concept of ‘hit compound’72 as it is widely accepted today needs to be expanded to address the needs imposed by the threat of antibacterial resistance. In this context, a hit compound is a molecule with reproducible activity, with a defined chemical structure (or set of structures), against one or more bacterial target(s). Although the selectivity and cytotoxicity of initial hits are seen as important characteristics, their improvement should remain tasks for the hit-to-lead optimization phase (see below). The activity of hits against (selected) pathogens must be proven in relevant assays, initially in vitro (for example, using exposed/isolated targets or a whole-cell approach), which can be complemented later in the process by the use of animal models of infection to evaluate pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) properties. In any event, the chemical identity and integrity of a hit must be demonstrated, whereas the actual target and the precise MoA may remain unknown until a later stage. Thus, the initial activity readout for a hit can be on either the molecular or the cellular level (Box 1).

When considering the definition of valuable hits, it is important to look beyond the simple model of a single molecule addressing one particular target. Compounds that hit multiple defined targets (known as polypharmacology73), or a combination therapy, in which the effects of several molecules are combined, can be equally valuable74. Depending on the target(s), hit combinations may act synergistically, preferably with different MoAs, or in an additive fashion. Such combinations can be useful in potentiating the activity of an existing antibiotic, slowing the onset of resistance and restoring the activity of antibiotics that have become inefficient because of resistance.

A major approach to identify novel hit compounds is by high-throughput screening of chemical libraries. It is important to select the correct set of compounds for each screen, for example, a (large) diverse set, a target-focused set or a fragment library. The make-up of a library should be based on specific characteristics or property space requirements, including chemical, structural and physicochemical aspects (Box 2); these may be tailored to a particular disease area75,76. We believe that carefully designed, and possibly even preselected (‘biased’), chemical libraries, which enable screening of a suitable chemical space against the bacterial target(s) of interest, represent an important first step to start a reliable hit identification campaign towards treatment of a specific bacterial infection. The design, assembly and curation of such libraries are costly processes that require the input of highly skilled practitioners. This frequently falls outside the funding range of most academic groups and, indeed, of many small companies. Models need to be found to grant access to the most useful libraries or compound collections for hit discovery, which should be facilitated at least for non-profit research entities.

Interactions and collaborations between academic researchers and pharmaceutical companies can accelerate hit discovery by, for example, using the high-throughput screening infrastructure of companies to interrogate novel targets. At the same time, pharmaceutical partners might search for close analogues of hits initially identified in academic labs, possibly together with existing biological and chemical property profiles. Such analogue series and accompanying data sets can be extremely valuable in enabling early improvement of antibacterial potency, as well as hit series validation. Pharmaceutical partners might also begin building profiles of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADMET) parameters, thus, accelerating the hit-to-lead transition. Sharing the relevant information will reinforce the efforts of medicinal chemistry and enhance its reliability and robustness. This, in turn, allows programmes to reach Go/No-Go decisions more quickly and can improve the chances of securing external funding or early partnering deals based on the impact of the medical need.

Notably, medicinal chemistry is the key discipline for the subsequent optimization of hits (see case studies in Boxes 1–4). A lack of sufficient funding and expertise to support medicinal chemistry at this early stage is highly detrimental for the entire translational process. Encouragingly, in 2016, a large number of pharmaceutical companies with interests in AMR signed the AMR Industry Declaration77, in which they jointly committed to support antibiotic R&D processes at virtually all stages. This has led to the formation of the AMR Industry Alliance (https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/). Additionally, the implementation of new AMR-specific capital resources, for example, through the REPAIR Impact Fund and the AMR Action Fund, and the direct involvement of PPPs like CARB-X in hit-to-lead campaigns during recent years should lead to intensified collaborations between industry and academia as a near-term goal to drive the chemical optimization of hits and leads forward towards new preclinical candidates.

Those academic groups that have already built the capacity to carry out such optimization efforts, including broad know-how in medicinal chemistry, biological assays and ADMET studies, would still benefit greatly from early partnering with biopharmaceutical companies, particularly as their projects will stand a greater chance of attracting external investment. Both not-for-profit initiatives, like the European Research Infrastructure Consortium for Chemical Biology and early Drug Discovery (EU-OPENSCREEN; https://www.eu-openscreen.eu/), and collaborative PPP models as implemented by the European Lead Factory (ELF)78,79, allowing for open drug discovery programmes based on Europe-wide screening resources (for example, the Joint European Compound Library, JECL), could pave the way for such early cross-sectoral interactions and exchanges for the benefit of all involved partners80.

Nature of the target

We recommend that hit identification against bacteria follows two convergent approaches: (i) identification of molecules active against molecular targets that are vital for all stages of the bacterial life cycle (‘essential targets’), thus, directly promoting clearance of the bacteria from the host/patient, and (ii) searching for molecules that inhibit so-called ‘non-essential targets’53,81,82. The latter can be defined as bacterial structures that are not vital under standard laboratory growth conditions but become critical during processes of host colonization and infection, for example, by regulating virulence development, by evading host immune response or by triggering bacterial defence mechanisms83. Molecules hitting such targets may have weak or even no activity towards bacterial cells under non-infectious (in vitro) screening conditions, but might display highly synergistic or additive effects when tested in relevant in vivo infection models, either alone or in combination with antibacterial agents addressing essential targets. The latter molecules may be found among the current antibacterial arsenal or may be new chemical entities, identified as described above.

Compounds interacting with non-essential targets are usually classified as antibiotic adjuvants, potentiators or resistance breakers84,85. Examples of non-essential target inhibitors are represented by:

-

(i)

Inhibitors of virulence-conferring factors or pathways (also known as anti-virulence compounds or pathoblockers86 that target, for example, quorum sensing mechanisms87, biofilm formation88, bacterial secretion systems89,90, enzymes for tissue penetration91 or intracellular survival92).

-

(ii)

Efflux pump inhibitors93.

- (iii)

-

(iv)

Inhibitors of pathways serving as a mechanism of defence, e.g. glutathione biosynthesis96,97.

- (v)

- (vi)

For some of the mentioned targets, such as efflux pumps, it has been demonstrated that their inhibition can reverse resistance to several antibacterials102. Therefore, an attractive therapeutic combination might be composed of a bactericidal agent and an adjuvant molecule, with the aim of potentiating the antibacterial effect(s) and significantly reducing resistance (either intrinsic or evolved)103. Since the pathoblocker approach is anticipated to be less susceptible towards resistance development and, in addition, to preserve the commensal bacteria of the microbiome86, it represents a non-traditional strategy for a focused disarming of resistant high-priority pathogens, most likely to be deployed as an adjunctive therapy in addition to antibiotic standard treatment81 (Box 3).

Advanced screening and profiling based on standardized assays

There is a fundamental need for assays to identify hit compounds (both synthetic and natural-product-based hits, the latter are addressed below) specifically for the clinically most relevant indications. In addition to using focused libraries that cover desirable chemical diversity and property space, innovative screens are essential to increase the chances for identifying potent hits against most prevalent common infections associated with Gram-positive or Gram-negative pathogens, such as hospital-acquired pneumonia, community-acquired pneumonia, complicated urinary tract infection or complicated intra-abdominal infection104. To establish a reliable foundation for future development, both academia and industry must use state-of-the-art library screening procedures based on generally accepted rules and basic concepts of standardization.

It is important that a range of relevant assays is used to thoroughly select and profile novel hit compounds. These assays should have a high physiological significance, which may be applicable to biomimetic assays105, for example, by using defined culture media such as artificial urine for activity screens with uropathogens106,107, iron-depleted media that simulate bacterial growth conditions during bloodstream or wound infections108,109 or assaying host–bacteria interactions110. Such schemes can further include the screening for new MoA(s), new drug sensitizing modes, non-killing mechanisms (e.g. anti-virulence factors like pathoblockers), compounds acting against biofilms and molecules acting synergistically with existing or new antimicrobials to overcome drug resistance111,112,113,114. Similarly, because hits generated by conventional biochemical assays or screens often fail to become whole-cell active leads, alternative phenotypic assays such as novel target-based whole-cell screening115 are also a promising foundation for the identification of useful hits. Even known chemical libraries (including proprietary compound archives of pharmaceutical companies), which have failed to deliver antibacterial hits by simple growth inhibition measurement, might bear fruit if reassayed following these approaches. The way in which these innovative screens are envisaged could make them a more appropriate strategy to provide novel hits with a potential therapeutic impact compared with the molecular-target-based drug design approach116.

A further aim of the consortium is to design and develop informative assays that can provide information about the desired antibacterial effect, together with further characteristics such as target engagement, bacterial penetration characteristics (for example, kinetics of compound permeation through Gram-negative cell envelope models117,118) and potential cytotoxicity.

In addition to devising standardized panels of assays according to contemporary technology, develo** the respective standard operating procedures (SOPs) is mandatory to meet the requirements for good research practice, which facilitates the transfer of compounds with potential to become new drugs from academia to non-profit or private organizations for continued development. By using standardized proof-of-concept assays under predefined SOPs, more robust hit series will emerge, increasing their potential for late-stage development and minimizing reproducibility issues. For example, minimum inhibitory concentrations, and possibly also minimum bactericidal concentrations, should always be evaluated in a screening campaign, for example, by using the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (https://eucast.org/) or the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (https://clsi.org/meetings/ast/) guidelines. In addition, selected hits from standard screening panels should be consequently tested against contemporary clinical isolates to demonstrate that they overcome existing resistance mechanisms.

Owing to the high attrition rates from early hit discovery to advanced hits and leads, it is especially important in the field of antibacterials to diversify and generate multiple hit series, and to characterize them thoroughly regarding all features that appear relevant to the intended therapeutic use. This includes explorations to expand scaffold diversity in the context of understanding the target-based chemical and physicochemical requirements, as well as potential liabilities, like ADMET.

A summary of early target hit profiles is essential to nominate the most valuable hit series acting against the pathogen(s) or medical indication(s) of interest. The selection of hit series for lead generation follows the target candidate profile (TCP), which is predefined at the outset of the development programme according to the desired target product profile (TPP) (Fig. 2). Thus, the optimization of hits should generally be driven by TCPs and compound progression criteria that, in turn, are driven by chosen TPPs. If several TPPs have been selected or outlined for a campaign, for example, based on different indications, together with their corresponding TCPs, it has to be decided which TCP should be used as a base to aim at for a given chemical series or possibly natural-product-based hit that emerges from mining of biological sources (see below).

Approaches marked with * can be linked with emerging artificial intelligence (AI)-based technology, for example, for advanced data mining, screening or property predictions, to increase efficiency and outcome. ADMET, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity; CTA, clinical trial application; DRF, dose range finding; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; FoR, frequency of resistance; GLP, good laboratory practice; ICH, International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use; IND, investigational new drug; MedChem, medicinal chemistry; MICs, minimal inhibitory concentrations; MoR, mechanism of resistance; phys-chem, physicochemical properties; PK/PD, pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics; POC, proof of concept; SAR, structure–activity relationship; TPP, target product profile.

It is important to implement physicochemical and in vitro ADMET profiling at the start of hit optimization, to make sure that any PK issues are identified early and can be addressed through the entire chemistry programme. In this respect, a standardized list of essential compound properties is required for successful transfer of hits and early leads into the following discovery and development stages. Depending on the defined TPP, such a dossier on physicochemical and biological properties should comprise a set of minimal criteria for compound progression based on selected, standardized assays or attributes with clear benchmarks for transition to the next stages in the drug discovery pathway and for continued (pre)clinical development according to the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) guidelines (https://www.ich.org/page/ich-guidelines). This will help to ensure developable compounds of clinical relevance are produced, which are also attractive for potential industrial partners. Relevant parameters (depending on the particular stage of transition) may include:

-

Potency/cellular activity (e.g. based on minimum inhibitory concentrations and minimum bactericidal concentrations).

-

Chemical and metabolic stability, solubility, permeability (e.g. based on logP or, for ionizable compounds, logD, or complex membrane partitioning).

-

Distribution, efflux avoidance, selectivity/off-target avoidance (e.g. inhibition assays on receptor panels, hERG etc.).

-

Acid/base properties based on pKa.

-

Cytotoxicity (especially human cell lines).

-

Lack of reactive metabolites.

-

Phototoxicity.

-

Protein binding.

-

In vivo efficacy and human dose prediction.

-

(Oral) bioavailability.

-

Genotoxicity (e.g. based on Ames or mouse micronucleus tests).

-

Drug–drug interactions.

-

PK linearity.

-

Safety (in vivo toxicity).

-

Compound access (e.g. synthetic feasibility and scaling up to gram or kilogram).

-

Achievable degree of purity.

-

Formulation.

Once the hit discovery transitions into the hit-to-lead and lead optimization phases (see below), it is necessary to enlarge the scope of biological studies. These may include bacterial killing kinetics, MoA, frequency of resistance, mechanism of resistance and PK/PD analyses, which will deliver valuable parameters to assess a compound’s in vivo efficacy (assuming sufficient free drug exposure in a relevant animal model with acceptable tolerability). At this level, it is, once again, important to acquire information on a substantial number of structurally related analogues through extensive medicinal chemistry efforts (perhaps in collaboration with PPPs or the pharmaceutical industry, as suggested above) in order to establish clear and reliable dossiers of structure–activity relationship (SAR) and structure–property relationship. These data are essential to consistently improve all the required parameters as a basis for a continuous advancement of lead structures towards the selection of (pre)clinical candidates. Computational methods based on machine learning techniques like profile-quantitative structure–activity relationship (pQSAR) can help to build predictive models regarding activity, selectivity, toxicity, MoA and further parameters for specific compound classes, hence, providing valuable in silico input for more effective hit discovery and lead design119,120.

Natural-product-based hit compounds

Historically, microbial natural products have been the most important source of antibiotic lead compounds; over the last 40 years, about 60% of all new chemical entities in the field of antibacterials were based on or derived from natural products121. Here, to complement the key aspects described above for synthetic hits, we outline the major requirements specific to the identification and prioritization of antibacterial natural product hits. We focus on efficiency and, particularly for the academic sector, achievability in terms of technological and financial demands.

Identification of new chemotypes from natural sources

The known antibiotic activity of natural products has, in general, been identified by phenotypic screening campaigns that determine activity against panels of test organisms in standardized assays. These screens, which constitute the basis for bioactivity-guided isolation of natural products from complex mixtures, efficiently retrieve bioactive compounds when libraries of crude extracts are evaluated. However, their ability to reveal useful novelty is limited by both a high rediscovery rate of already known molecules associated with pre-existing resistance mechanisms, as well as a substantial proportion of hits that show significant cytotoxicity or poor ADMET properties.

We emphasize that there is a general lack of efficient tools and strategies to increase the number of new chemotypes and to reduce the rediscovery rates in antibacterial screening approaches. Even on a global scale, the number of newly discovered chemotypes, especially novel scaffolds acting against Gram-negative bacteria, is consistently low. Several approaches are relevant to improve this situation:

One possibility to enforce the identification of new antibacterial chemistry is to limit screening of already broadly characterized groups of secondary metabolite producers, for example, actinomycetes, and to expand efforts on identifying new types of producers by extensive biodiversity mining. This can be achieved by focusing on the ~99.999% of microbial taxa of the Earth’s microbiome that remain undiscovered122,123, including the as yet underexplored taxa of human and animal microbiomes124,125,126,127. Emerging innovative isolation and cultivation techniques such as diffusion bioreactors (also carried out on the microscale as with the iChip128,129,130), microfluidics131,132,133, elicitors134 and various co-cultivations135,136 will help to access and understand the rare and less-studied groups of microorganisms from diverse habitats137,138,139. Further, molecular (co-)evolution acting to generate novel metabolites for efficient microbial warfare could be exploited140,141, for example, by sampling from environments heavily contaminated with antibiotics (like sewage in Southeast Asia or South America), which are known to contain highly resistant microbes142,143. Complementarily, this can be achieved by laboratory exposure of potent producers to subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations144 or by co-culturing them together with drug-resistant (pathogenic) strains145. Beyond microbial producers, a great variety of plants146,147, macroscopic filamentous fungi (e.g. Basidiomycota)148 and animals149 bear the potential to deliver useful compounds as a base for novel antimicrobials. Altogether, the exploration of untapped biological resources, which represent a major reservoir for future therapeutics, should generally be extended within the academic and industrial sector.

After genome mining of novel microbial isolates or metagenome-driven discovery of novel natural products150,151,152,153, selected biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that potentially produce unknown secondary metabolites should be systematically expressed in specialized heterologous host strains154,155,156. This helps to facilitate a straightforward detection and isolation of the new compounds, particularly if their BGCs are ‘silent’ (i.e. not expressed under known conditions) in the native host. Such heterologous hosts or chassis strains can be based on microbial species that commonly produce a large variety of natural products, but have been made devoid of their own secondary metabolite BGCs and/or have been further optimized to efficiently express BGCs originating from ‘non-common’ sources (for example, rare actinomycetes or fungi)154,157,158. However, only a limited set of such specialized host strains is available so far, and a much more diverse array of microbial chassis needs to be developed to fit the demands of a growing arsenal of BGCs that potentially produce novel chemistry. BGC expression is often most successful in strains closely related to the native producer, and, thus, it is important to develop methods for standardized heterologous expression in selected host strains with desirable properties that have not yet been domesticated for the use as regular chassis159.

Chemical space can also be enlarged by using emerging synthetic biology approaches for medium-to-high-throughput genome editing and pathway engineering. These approaches, which are primarily based on CRISPR/Cas9 (refs160,161) and diverse recombination, assembly and integrase systems162,163,164, can be followed up with advanced analytics and screening of the potentially modified natural products, which may be produced in only trace quantities. This technology involves the extensive use of information on genome sequences, enzyme activities and compound structures collected by publications, databases and web tools (such as MIBiG165, antiSMASH166 and PRISM167) over the past few decades. In many cases, the modularity of the BGC composition, which is found in gene clusters, for example, coding for polyketide synthases or non-ribosomal peptide synthetases, can be used to implement a bioinformatics-supported plug-and-play diversification strategy enabling the exchange and recombination of core units, as well as modifying enzymes168,169,170,171. A concomitant refactoring of BGCs, especially from rare microbial sources, often allows high-level heterologous production of the antibiotic compounds in suitable hosts172,173,174,175. However, these methods are still in their infancy and require wider testing with different classes of antimicrobials to define general principles of feasibility and scalability, which, furthermore, necessitates an improved understanding of the complex biosynthetic machineries and their modular evolution.

Advances in analytical chemistry techniques, for example, in mass-spectrometry-based metabolomics and its enhancement by molecular networking and the application of machine learning, support the process of dereplication176 during (secondary) metabolome mining177,178,179,180,181. Known compounds produced in reasonably high yields can be rapidly identified via their high-resolution masses, tandem mass spectrometry fragmentation patterns or structural data in secondary metabolite databases138,182,183,184,185,186,187. However, the remaining bottleneck is to highlight and annotate novel antibiotic compounds, particularly those with low production titres, as early as possible in the discovery process (i.e. from crude extracts if possible, without the need for small-scale fractionation and enrichment). This objective can be supported by innovative extraction methods prior to bioactivity-guided isolation of novel compounds188.

In addition, revisiting known potent antibiotics, previously neglected as a result of unacceptable or non-addressable properties such cytotoxicity or lack of stability, can be a valuable strategy to provide novel leads and candidates. The reassessment of such scaffolds can be based on a variety of efforts, including the improvement of production and purification189, reconsideration of application and effective dose for natural derivatives190, or advantageous scaffold modification by biosynthetic engineering and semi-synthetic approaches191,192 (Box 4).

Further opportunities remain to improve the discovery and development of agents for combination therapy as indicated above, i.e. compounds that act synergistically against multidrug-resistant and/or high-priority pathogens193,194. The discrimination of specific synergistic activities from non-specific antibiotic activities remains a challenge during the discovery process.

Improving bacterial target access, enhancing potency and broadening the antimicrobial spectrum of known and novel antibiotic scaffolds can be achieved by using drug-conjugate strategies, for example, linking of pathogen-specific antibodies195,196, siderophore moieties197,198 or positively charged peptides199,200 to the antibiotic core scaffold. Though these approaches have been proven effective in a number of cases, some of them may also have unintended effects, such as a spontaneously increasing frequency of resistance, which can be problematic, for example, in the case of the Trojan Horse approach201.

Overall, a variety of innovative and complementary technologies is required to improve access to novel natural product scaffolds. Computational methods can provide powerful assistance at different levels in many of the areas indicated above, as recent efforts show202,203. In this context, artificial intelligence might play a game-changing role in the future. The general power of neural networks for detecting new antimicrobial candidates has already been demonstrated202. By using a computational model that screens hundreds of millions of chemical compounds in a few days, potential antibiotics even with new MoA(s) could be proposed rapidly. Given the recent advances in artificial intelligence, these and other models will likely add to the future identification of new candidate drugs.

Interestingly, when looking at compound properties, it appears that there is often more flexibility in the selection of ‘successful’ natural product scaffolds compared with synthetics, for example, regarding Lipinski’s rule of five204,205,206, which natural products frequently ‘disobey’ (such as cyclosporine or macrolides like azithromycin). Thus, antimicrobial drug discovery in ‘beyond rule of five’ chemical space is an opportunity when using natural compound collections or when assembling libraries of de novo designed compounds207,208,209, though the general need for optimizing key pharmacological properties of such hits remains beyond question.

Another major challenge for natural products can be the generation of structurally diverse analogues (particularly if they are not accessible through biosynthesis). Many scaffold positions can be difficult to access by means of semi-synthesis and, thus, broad derivatization of natural-product-based hit and lead compounds is often much more labour-intensive, and establishing synthetic access to these scaffolds with a focus on the ability to systematically diversify their chemical space can require large amounts of resources210. Nevertheless, the modification of natural scaffolds with substituents that are often easier to incorporate by (semi-)synthetic or chemoenzymatic approaches, such as halogens that allow the modulation of solubility, permeability, selectivity, target affinity etc.211,212, proves that multiple opportunities arise when combining synthetic and biological chemistry.

Required access to biological and chemical material and data

Many scientists frequently experience difficulty in accessing and sharing research material from third parties, including microbial strains, cultivation extracts, pure compounds, genome or gene cluster sequences and further background data (of published or even unpublished results). For example, an interesting BGC is identified in publicly accessible databases, but the strain is not specified or not available from the indicated source. Similarly, access to industrial antibiotic overproducers can be impossible, even when a company no longer has a commercial interest in the resulting molecule. This phenomenon has several origins, including legal restraints (for example, imposed by the Nagoya Protocol213) or intellectual property (IP) claims on strains, compounds, biologics or (re)profiling data of already known structures.

In the public interest, standardized procedures are necessary to facilitate access to research materials and to solve IP conflicts, at least within the field of academia, in which it is common practice to share research materials with colleagues by negotiating appropriate cooperation agreements.

Further, the access to in-house compound libraries of pharmaceutical companies (at least subsets of them and especially those that are not intended for antibiotic-related screening) could be very valuable for academic partners who are eager to identify novel antibacterial hits, which could lead to joint drug development programmes. Enabling access to materials can also be extended to strain collections, including clinical isolates representing the diversity of pathogens associated with a certain clinical indication, and advanced compound information based on pre-existing characterization and profiling campaigns. An increased availability of these resources will be of great benefit to the antimicrobial research community worldwide.

Furthermore, comprehensive databases and data-sharing platforms can provide another valuable resource for present and future antibiotic R&D projects and, hence, should be implemented and maintained with care214. There is a growing body of recently initiated and publicly available web-based tools and archives that support accumulation and exchange of data regarding antibacterial compounds in different stages of discovery or therapeutic development, known or predicted antibiotic targets and the diversity of antimicrobial resistance determinants (Box 5). Further connection and integration of such databases is desirable to optimize the output for a specific search request. In addition, initiatives comparable with the European Commission’s manifesto to maximize the public accessibility of research results in the fight against COVID-19 (ref.215) are also highly recommended to support AMR-related scientific research at all levels, including facilitated access to online resources.

Prediction of antimicrobial structure and function from genome sequence data

Driven by breakthroughs in sequencing technologies and genome mining, the identification of BGCs encoding the biosynthesis of natural products has matured to complement the chemistry-driven and bioactivity-driven screening processes for natural product hits. Computational methods are established and continuously improved to identify novel biosynthetic pathways in (meta)genomic sequence data150,151. Recently, third-generation genome sequencing techniques such as PacBio and Oxford Nanopore have been developed that provide high-quality full genome data even for complex microorganisms like filamentous fungi at reasonable cost, which is an ideal prerequisite for large-scale genome mining approaches216.

However, linking the obtained sequence information to possible structural or functional features of the encoded molecules remains a great challenge. Prediction of chemical structures directly from genome data would help to distinguish known from potentially novel scaffolds during a very early stage of dereplication; the training of machine learning algorithms with sufficient quantity of genome data from microbial producers could ultimately lead to fairly accurate predictions of chemical structures linked to specific BGCs and possibly even their biological activities167.

A successful strategy to decipher antibacterial targets of new natural products, without the need to isolate them, is a directed search for known resistance factors in the genomes of antibiotic-producing microbes217,218. These producers may code for resistant variants of the molecular target(s) that interact with the intrinsic antibiotic(s) without damaging the host or conserved class-specific transporters that release the compound(s) into the environment. This approach recently led to the discovery of novel antibiotic scaffolds219. However, most BGCs do not contain apparent or specific drug-resistance genes that could straightforwardly indicate a compound’s function. In the majority of cases, very limited predictions based on genomic data concerning function and potential target(s) of a natural product are currently possible, although advanced automated tools for target-directed genome mining are available220. Thus, there is a high demand for innovative methods to predict the molecular function or target of a natural compound based on genomic data. Such data would be extremely valuable in order to prioritize BGCs for experimental characterization. In the future, artificial intelligence approaches, based on either classical machine learning methods (extracting new knowledge from preprocessed data sets) or on deep learning (drawing conclusions from raw data such as representative examples, often by using multilayer neural networks), may deliver such predictions with increasing accuracy221. However, existing algorithms need to be improved, and new ones have to be developed to specifically address the question of how to assign target-based functions to natural products with confidence during the early stages of discovery and prioritization. These approaches also require a huge amount of validated training data222.

Advancing hits to (pre)clinical status

Regardless of whether antibacterial hits emerge from rationally designed synthetic molecules or from the pool of natural products, the subsequent hit-to-lead and lead-to-candidate optimization phases are very similar for compounds irrespective of origin (‘Y model’, see Fig. 2). We now discuss the most critical obstacles and requirements for delivering those advanced leads that may eventually become the next generation of (pre)clinical candidates.

Drug–target interaction studies as a base for hit development

For hits arising from phenotypic assays, cellular MoA(s) or specific molecular target(s) may not be known at the hit-to-lead stage, and, sometimes, the precise MoA is elucidated years after the approval of a drug, as in the case of daptomycin223. However, detailed insight into the mechanism(s) by which compounds exert their pharmacological activity is highly desirable for further rational optimization of chemical scaffolds, particularly when structurally enabled approaches can be used, for a convincing presentation of preclinical candidate dossiers and for regulatory requirements. Since universally applicable methods for characterizing the MoA(s) of antibiotics do not exist, a full suite of expertise in genetics, genomics, microbiology, chemical biology and biophysics is required. Identification of the molecular target can be achieved by targeted screens of indicator or mutant strains, whole-genome sequencing upon focused resistance development224,225, pattern recognition techniques based on transcriptomics226, imaging227,228, metabolomics229, macromolecular synthesis230,231 or mutant fitness profiles232,233, which can be coupled with machine learning approaches for directed predictions225,233, or chemoproteomics234,235. The latter is specifically useful in the case of non-essential target inhibitors like pathoblockers, since these may not generate resistant mutants (at least under standard laboratory conditions). Additional techniques for MoA studies may include crystallography, a diverse set of spectroscopic and calorimetric analyses236,237,238,239,240, as well as the use of functionalized derivatives (‘tool compounds’)241,242, which can support both target identification and validation and may provide in-depth information of drug–target interactions to drive the rational hit-to-lead optimization process forward. Alternatively, identification of drug–target (or ligand–protein) interactions formed under native (unbiased) conditions by using specialized proteomic approaches is becoming increasingly successful243,244,245,246. Current bioinformatic tools can also combine genome-mining approaches with the prediction of potentially innovative MoA(s) based on the presence of resistant target genes in BGCs encoding novel antibiotics220. These and other examples illustrate how a diverse set of emerging learning methods is steadily enhancing the predictability of drug–target interactions247,248.

In addition to the specific molecular target(s), it is important to understand the impact of the antibiotic compound on the general physiology of the bacterial cell. This includes the sequence of events leading to bacterial death, the time point when killing occurs (based on either individual bacterial cells or their population/colonization level) and the conditions that might enhance or preclude it. Such characterizations may require the application or development of a range of secondary assays. For compounds acting on intracellular bacterial targets (i.e. targets located in the cytoplasm), the processes of compound influx and prevention of efflux (especially so for Gram-negative bacteria as a result of their complex cell envelope and presence of numerous multidrug efflux pumps) are both critical optimization parameters to ensure sufficient target engagement249,250,251,252,253. These factors can be addressed by suitable compound design, which generally remains rather empirical and challenging254,255,256,257. Other possibilities to address this key area would be to use these compounds in combination with outer membrane permeabilizing agents258,259 or efflux inhibitors93,260. Alternative approaches targeting extracellular virulence factors, for example, extracellular lectins required for attachment and biofilm formation or secreted proteolytic enzymes, do not suffer from a possible lack of bacterial uptake261. Often, antibiotics, and particularly natural products, have more than one target and disturb bacterial physiology in several different pathways, a phenomenon referred to as polypharmacology73,44,121. Regrettably, fermentation-independent supply, for example, through the total synthesis of complex natural compounds, can only be achieved for a low percentage of novel hits and leads and requires a tremendous amount of additional capacity and resources279,280,281,282.

Thus, suitable funding instruments are needed to cover the essential processes of natural compound scale-up and supply based on biotechnological methods, including large-scale fermentation and efficient downstream processing283,284,285, towards obtaining high-quality source material for semi-synthesis and further studies. In addition, a robust method for large-scale production and downstream processing of the candidate molecule is a prerequisite for process transfer to good manufacturing practice (GMP) production before entering (pre)clinical stages. Generally, further scientific and technological development is required to make the provision of compound material from various sources a more routine and affordable task, particularly in the non-industrial research environment.

Requirements for in vivo studies and project transfer

The primary assays in most discovery programmes usually address biochemical, biophysical and/or microbiological functionality of newly generated compounds. In order to convert a molecule with in vitro activity into a drug, sufficient exposure at the infection site in vivo must be achieved. To analyse this, a full suite of ADMET assays is required286,287, followed by pharmacokinetics experiments in animals (usually starting with rodent models)288,289, which can be combined with physiologically based PK modelling and in silico ADMET prediction290,314,315,316.

For the above reasons, we recommend that an international group of experienced AMR lobbyists should be formed that, together, can campaign for funding of early antibacterial drug discovery research along the principles set out in this article. Such a group should include national, regional and global scientific and industry associations that have practice in interacting with relevant stakeholders connected with national parliaments, EC, G7, G20 and further decision-making entities317. The Global AMR R&D Hub (https://globalamrhub.org/) could be a crystallization point to pioneer such developments, which can be supported by various consortia, including the authors of this article: The International Research Alliance for Antibiotic Discovery and Development (IRAADD; https://www.iraadd.eu/), which we have recently established with the support of the JPIAMR Virtual Research Institute (JPIAMR-VRI; https://www.jpiamr.eu/jpiamr-vri/), identifies itself as a part of the mission that is addressed by the current roadmap. The IRAADD aims to improve the situation of novel antibiotic discovery and development by bringing together experts for early drug research from the academic and industrial sectors, who can provide knowledge and advice for diverse projects in the field. A recent example of our activities is the support of the JPIAMR-VRI to create a new online resource (the JPIAMR-VRI Digital Platform ‘DISQOVER’; https://www.jpiamr.eu/activities/jpiamr-vri/digital-platform/), serving as a comprehensive and interlinked database for AMR-related research at multiple levels. Although the IRAADD currently has only a short-term funding perspective, it is one of our main goals to help define and implement interdisciplinary innovative antibiotic development programmes based on sustainable research funding, in order to refill the translational pipeline with new drug candidates in the foreseeable future. In this respect, and as a possible long-term vision, the creation of internationally operating antibiotic research hubs, which may emerge from already existing pre-stage platforms such as the IRAADD, can be a major step forward to engage as many members as possible from academia, industry and public health organizations in antimicrobial R&D collaborations, and to create a strong and path-breaking position that cannot be overlooked. Only a responsible connection of thought leaders and dedicated experts from all relevant sectors of society, joining together now and for the future, will allow suitable rapid responses to globally emerging pathogens. Therefore, taking corrective and preventive action now through concerted and innovative approaches in the field of novel antibiotic drug discovery and development is the essential path forward to be prepared for future pandemics caused by multi-to-pan drug-resistant (so-called superbug) bacteria, which is an aim that deserves our undivided attention.

References

Ventola, C. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm. Ther. 40, 277–283 (2015). A comprehensive summary of the emergence of antibiotic resistance and the associated clinical and economic burden.

Byrne, M. K. et al. The drivers of antibiotic use and misuse: the development and investigation of a theory driven community measure. BMC Public. Health 19, 1425 (2019).

Nadimpalli, M. L. et al. Urban informal settlements as hotspots of antimicrobial resistance and the need to curb environmental transmission. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 787–795 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO report on surveillance of antibiotic consumption 2016–2018 early implementation (WHO, 2018) https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/rational_use/oms-amr-amc-report-2016-2018/en/

Schrader, S. M., Vaubourgeix, J. & Nathan, C. Biology of antimicrobial resistance and approaches to combat it. Sci. Trans. Med. 12, eaaz6992 (2020).

Conlon, B. P. et al. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16051 (2016).

Harms, A., Maisonneuve, E. & Gerdes, K. Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354, aaf4268 (2016).

Blaskovich, M. A. T. Antibiotics special issue: challenges and opportunities in antibiotic discovery and development. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1286–1288 (2020). An excellent special issue combining viewpoints, perspectives, reviews and original research to provide a snapshot of the current state of antibiotic discovery and development.

O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (2016). Ground-breaking report and action plan to tackle present and future threats imposed by drug-resistant infections on a global scale.

AMR Industry Alliance. 2020 progress report (AMR Industry Alliance, 2020) https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/AMR-2020-Progress-Report.pdf

Zhou, P. et al. Bacterial and fungal infections in COVID-19 patients: A matter of concern. Infect. Control Hospital Epidemiol. 41, 1124–1125 (2020).

Chen, X. et al. The microbial coinfection in COVID-19. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 104, 7777–7785 (2020).

Zhou, F. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1054–1062 (2020).

Nori, P. et al. Emerging co-pathogens: New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase producing Enterobacterales infections in New York City COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56, 106179 (2020).

Getahun, H., Smith, I., Trivedi, K., Paulin, S. & Balkhy, H. H. Tackling antimicrobial resistance in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bull. World Health Organ. 98, 442–442A (2020).

Oldenburg, C. E. & Doan, T. Azithromycin for severe COVID-19. Lancet 396, 936–937 (2020).

Yates, P. A. et al. Doxycycline treatment of high-risk COVID-19-positive patients with comorbid pulmonary disease. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 14, 1753466620951053 (2020).

Sodhi, M. & Etminan, M. Therapeutic potential for tetracyclines in the treatment of COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 40, 487–488 (2020).

Baron, S. A., Devaux, C., Colson, P., Raoult, D. & Rolain, J.-M. Teicoplanin: an alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55, 105944 (2020).

Contou, D. et al. Bacterial and viral co-infections in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia admitted to a French ICU. Ann. Intensive Care 10, 119 (2020).

Sharifipour, E. et al. Evaluation of bacterial co-infections of the respiratory tract in COVID-19 patients admitted to ICU. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 646 (2020).

Langford, B. J. et al. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: a living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 1622–1629 (2020).

Rawson, T. M. et al. Bacterial and fungal co-infection in individuals with coronavirus: A rapid review to support COVID-19 antimicrobial prescribing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 2459–2468 (2020).

Vaughn, V. M. et al. Empiric antibacterial therapy and community-onset bacterial co-infection in patients hospitalized with COVID-19: a multi-hospital cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, e533–e541 (2020).

Hsu, J. How covid-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ 369, m1983 (2020).

Rawson, T. M., Ming, D., Ahmad, R., Moore, L. S. P. & Holmes, A. H. Antimicrobial use, drug-resistant infections and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 409–410 (2020).

Bengoechea, J. A. & Bamford, C. G. SARS-CoV-2, bacterial co-infections, and AMR: the deadly trio in COVID-19? EMBO Mol. Med. 12, e12560 (2020).

Huttner, B. D., Catho, G., Pano-Pardo, J. R., Pulcini, C. & Schouten, J. COVID-19: don’t neglect antimicrobial stewardship principles! Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 808–810 (2020).

Buehrle, D. J. et al. Antibiotic consumption and stewardship at a hospital outside of an early coronavirus disease 2019 epicenter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e01011–e01020 (2020).

Nieuwlaat, R. et al. COVID-19 and antimicrobial resistance: parallel and interacting health emergencies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, 1657–1659 (2020).

Bassetti, M. & Giacobbe, D. R. A look at the clinical, economic, and societal impact of antimicrobial resistance in 2020. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 21, 2067–2071 (2020).

Magiorakos, A.-P. et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 268–281 (2012). This article presents the standardized international terminology to describe acquired resistance profiles in bacterial priority pathogens.

**n Yu, J., Hubbard-Lucey, V. M. & Tang, J. Immuno-oncology drug development goes global. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 899–900 (2019).

The Pew Charitable Trusts. Tracking the global pipeline of antibiotics in development, April 2020 (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2020) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2020/04/tracking-the-global-pipeline-of-antibiotics-in-development

Beyer, P. & Paulin, S. The antibacterial research and development pipeline needs urgent solutions. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1289–1291 (2020).

World Health Organization (WHO). 2019 Antibacterial agents in clinical development: an analysis of the antibacterial clinical development pipeline. (WHO, 2019) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330420/9789240000193-eng.pdf

The Pew Charitable Trusts. A scientific roadmap for antibiotic discovery. (The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016) https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2016/05/a-scientific-roadmap-for-antibiotic-discovery

OECD Publishing. Stemming the superbug tide: Just a few dollars more. (OECD, 2018) https://www.oecd.org/health/stemming-the-superbug-tide-9789264307599-en.htm

Årdal, C. et al. DRIVE-AB report: revitalizing the antibiotic pipeline: Stimulating innovation while driving sustainable use and global access. (DRIVE AB, 2018) http://drive-ab.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CHHJ5467-Drive-AB-Main-Report-180319-WEB.pdf

Kim, W., Prosen, K. R., Lepore, C. J. & Coukell, A. On the road to discovering urgently needed antibiotics: so close yet so far away. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1292–1294 (2020).

Theuretzbacher, U., Outterson, K., Engel, A. & Karlén, A. The global preclinical antibacterial pipeline. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 275–285 (2020). This review summarizes the most recent antibacterial discovery and preclinical development projects in academia and industry on a global scale.

O’Neill, J. Securing new drugs for future generations: the pipeline of antibiotics. (The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2015) https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/SECURING%20NEW%20DRUGS%20FOR%20FUTURE%20GENERATIONS%20FINAL%20WEB_0.pdf

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W. & Wilkinson, B. Antibiotics: past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 51, 72–80 (2019).

Lewis, K. The science of antibiotic discovery. Cell 181, 29–45 (2020). Outstanding overview of past achievements as well as current perspectives and challenges in the field of antibiotic discovery.

Coates, A. R. M., Halls, G. & Hu, Y. Novel classes of antibiotics or more of the same? Br. J. Pharmacol. 163, 184–194 (2011).

Hughes, D. & Karlén, A. Discovery and preclinical development of new antibiotics. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 119, 162–169 (2014).

Jackson, N., Czaplewski, L. & Piddock, L. J. V. Discovery and development of new antibacterial drugs: learning from experience? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1452–1459 (2018).

Payne, D. J., Gwynn, M. N., Holmes, D. J. & Pompliano, D. L. Drugs for bad bugs: confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 29–40 (2007).

BEAM Alliance. Supporting financial investments on R&D to de-risk antimicrobial development. (BEAM Alliance, 2019) https://beam-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/the-beam-push-memo.pdf

Shlaes, D. M. Antibacterial drugs: the last frontier. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1313–1314 (2020).

Rex, J. H. & Outterson, K. Antibiotic reimbursement in a model delinked from sales: a benchmark-based worldwide approach. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 500–505 (2016). This article describes how delinkage models should be built to ensure the development of antibiotics with the greatest possible innovative potential.

Outterson, K. A shot in the arm for new antibiotics. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 1110–1112 (2019).

Rex, J. H., Fernandez Lynch, H., Cohen, I. G., Darrow, J. J. & Outterson, K. Designing development programs for non-traditional antibacterial agents. Nat. Commun. 10, 3416 (2019). This article discusses strategies focusing on how non-traditional antibacterial products can best be developed.

Årdal, C. et al. Antibiotic development - economic, regulatory and societal challenges. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 267–274 (2020).

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) New AMR Action Fund steps in to save collapsing antibiotic pipeline with pharmaceutical industry investment of US$1 billion. (IFPMA, 2020) https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/new-amr-action-fund-steps-in-to-save-collapsing-antibiotic-pipeline/

The Public Health Agency of Sweden. Availability of antibiotics: Reporting of Government Commission. (The Public Health Agency of Sweden, 2017) https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/contentassets/ab79066a80c7477ca5611ccfb211828e/availability-antibiotics-01229-2017-1.pdf

Mullard, A. UK outlines its antibiotic pull incentive plan. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 298–299 (2020).

Mahase, E. UK launches subscription style model for antibiotics to encourage new development. BMJ 369, m2468 (2020).

Bennet, S. M. & Young, S. T. The Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Up Surging Resistance Act of 2020. (The PASTEUR Act. Michael Bennet, U.S. Senator for Colorado); https://www.bennet.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/b/5/b5032465-bf79-4dca-beba-50fb9b0f4aee/C1FD8B8C4143F1332DC6A5E5EC09C83B.bon20468.pdf (2020).

Davis, D. K. Develo** an Innovative Strategy for Antimicrobial Resistant Microorganisms Act of 2019. DISARM Act of 2019. (Congress.gov, 2019) https://www.congress.gov/116/bills/hr4100/BILLS-116hr4100ih.pdf (2019).

Balasegaram, M. & Piddock, L. J. V. The Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP) not-for-profit model of antibiotic development. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1295–1298 (2020).

Alm, R. A. & Gallant, K. Innovation in antimicrobial resistance: the CARB-X perspective. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1317–1322 (2020).

Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) AMR Accelerator Programme. Collaboration for prevention and treatment of multi-drug resistant bacterial infections (COMBINE, 2019). https://amr-accelerator.eu/project/combine/

BEAM Alliance. BEAM Alliance and global partners call for urgent action on new reimbursement models for life-saving antibiotics. (BEAM Alliance, 2020) https://beam-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/post-amr-conference-paper.pdf

Engel, A. Fostering antibiotic development through impact funding. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1311–1312 (2020).

Zuegg, J., Hansford, K. A., Elliott, A. G., Cooper, M. A. & Blaskovich, M. A. T. How to stimulate and facilitate early stage antibiotic discovery. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1302–1304 (2020).

van Hengel, A. J. & Marin, L. Research, innovation, and policy: an alliance combating antimicrobial resistance. Trends Microbiol. 27, 287–289 (2019).

Simpkin, V. L., Renwick, M. J., Kelly, R. & Mossialos, E. Incentivising innovation in antibiotic drug discovery and development: progress, challenges and next steps. J. Antibiot. 70, 1087–1096 (2017).

BEAM Alliance. Incentivising a sustainable response to the threat of AMR. (BEAM Alliance, 2019) https://beam-alliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/the-beam-pull-memo.pdf

European Commission. A European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance. (AMR). (European Commission, 2017) https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/antimicrobial_resistance/docs/amr_2017_action-plan.pdf

World Health Organization (WHO). Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. (WHO, 2015) https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/

Hughes, J. P., Rees, S., Kalindjian, S. B. & Philpott, K. L. Principles of early drug discovery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 1239–1249 (2011).

Reddy, A. S. & Zhang, S. Polypharmacology: drug discovery for the future. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 6, 41–47 (2013). This review outlines the latest progress and challenges in polypharmacology studies.

Tyers, M. & Wright, G. D. Drug combinations: a strategy to extend the life of antibiotics in the 21st century. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 141–155 (2019).

O’Shea, R. & Moser, H. E. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 51, 2871–2878 (2008).

Reck, F., Jansen, J. M. & Moser, H. E. Challenges of antibacterial drug discovery. Arkivoc 2019, 227–244 (2020). This study highlights challenges in the discovery of antibiotics, with a focus on physicochemical parameters and preferred property space.

AMR Industry Alliance. Declaration by the pharmaceutical, biotechnology and diagnostics industries on combating antimicrobial resistance. (AMR Industry Alliance, 2016) https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/AMR-Industry-Declaration.pdf

Karawajczyk, A., Orrling, K. M., Vlieger, J. S. B., de, Rijnders, T. & Tzalis, D. The European lead factory: a blueprint for public-private partnerships in early drug discovery. Front. Med. 3, 75 (2016).

Morgentin, R. et al. Translation of innovative chemistry into screening libraries: an exemplar partnership from the European Lead Factory. Drug Discov. Today 23, 1578–1583 (2018).

Besnard, J., Jones, P. S., Hopkins, A. L. & Pannifer, A. D. The Joint European Compound Library: boosting precompetitive research. Drug Discov. Today 20, 181–186 (2015).

Theuretzbacher, U. & Piddock, L. J. V. Non-traditional antibacterial therapeutic options and challenges. Cell Host Microbe 26, 61–72 (2019). Comprehensive overview of non-traditional approaches in antibacterial therapy.

Fleitas Martínez, O., Cardoso, M. H., Ribeiro, S. M. & Franco, O. L. Recent advances in anti-virulence therapeutic strategies with a focus on dismantling bacterial membrane microdomains, toxin neutralization, quorum-sensing interference and biofilm inhibition. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9, 74 (2019).

Kumar, A., Ellermann, M. & Sperandio, V. Taming the beast: Interplay between gut small molecules and enteric pathogens. Infect. Immun. 87, e00131-19 (2019).

Laws, M., Shaaban, A. & Rahman, K. M. Antibiotic resistance breakers: current approaches and future directions. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 43, 490–516 (2019).

Annunziato, G. Strategies to overcome antimicrobial resistance (AMR) making use of non-essential target inhibitors: a review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 5844 (2019).

Calvert, M. B., Jumde, V. R. & Titz, A. Pathoblockers or antivirulence drugs as a new option for the treatment of bacterial infections. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 14, 2607–2617 (2018).

Schütz, C. & Empting, M. Targeting the Pseudomonas quinolone signal quorum sensing system for the discovery of novel anti-infective pathoblockers. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 14, 2627–2645 (2018).

Sommer, R. et al. Glycomimetic, orally bioavailable LecB inhibitors block biofilm formation of pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2537–2545 (2018). Example of synthetic pathoblockers acting against biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Boudaher, E. & Shaffer, C. L. Inhibiting bacterial secretion systems in the fight against antibiotic resistance. MedChemComm 10, 682–692 (2019).

Duncan, M. C., Linington, R. G. & Auerbuch, V. Chemical inhibitors of the type three secretion system: disarming bacterial pathogens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5433–5441 (2012).

Schönauer, E. et al. Discovery of a potent inhibitor class with high selectivity toward clostridial collagenases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12696–12703 (2017).

Paolino, M. et al. Development of potent inhibitors of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence factor Zmp1 and evaluation of their effect on mycobacterial survival inside macrophages. ChemMedChem 13, 422–430 (2018).

Marshall, R. L. et al. New multidrug efflux inhibitors for Gram-negative bacteria. mBio 11, e01340-20 (2020).

Bush, K. & Bradford, P. A. Interplay between β-lactamases and new β-lactamase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 295–306 (2019).

Tooke, C. L. et al. β-Lactamases and β-lactamase inhibitors in the 21st century. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3472–3500 (2019).

Smirnova, G. V. & Oktyabrsky, O. N. Glutathione in bacteria. Biochemistry 70, 1199–1211 (2005).

Chen, N. H. et al. A glutathione-dependent detoxification system is required for formaldehyde resistance and optimal survival of Neisseria meningitidis in biofilms. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 18, 743–755 (2013).

Lu, P. et al. The anti-mycobacterial activity of the cytochrome bcc inhibitor Q203 can be enhanced by small-molecule inhibition of cytochrome bd. Sci. Rep. 8, 2625 (2018).

Iqbal, I. K., Bajeli, S., Akela, A. K. & Kumar, A. Bioenergetics of Mycobacterium: an emerging landscape for drug discovery. Pathogens 7, 24 (2018).

Fol, M., Włodarczyk, M. & Druszczyn´ska, M. Host epigenetics in intracellular pathogen infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4573 (2020).

Ghosh, D., Veeraraghavan, B., Elangovan, R. & Vivekanandan, P. Antibiotic resistance and epigenetics: more to it than meets the eye. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e02225-19 (2020).

Venter, H. Reversing resistance to counter antimicrobial resistance in the World Health Organisation’s critical priority of most dangerous pathogens. Biosci. Rep. 39, BSR20180474 (2019).

Rezzoagli, C., Archetti, M., Mignot, I., Baumgartner, M. & Kümmerli, R. Combining antibiotics with antivirulence compounds can have synergistic effects and reverse selection for antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000805 (2020).

Strich, J. R. et al. Needs assessment for novel Gram-negative antibiotics in US hospitals: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 1172–1181 (2020).

Lakemeyer, M., Zhao, W., Mandl, F. A., Hammann, P. & Sieber, S. A. Thinking outside the box — novel antibacterials to tackle the resistance crisis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14440–14475 (2018). Extensive and interdisciplinary overview of methods for mining novel antibiotics and strategies to unravel their modes of action.

Hennessen, F. et al. Amidochelocardin overcomes resistance mechanisms exerted on tetracyclines and natural chelocardin. Antibiotics 9, 619 (2020).

Sarigul, N., Korkmaz, F. & Kurultak, I∙. A new artificial urine protocol to better imitate human urine. Sci. Rep. 9, 20159 (2019).

Ganz, T. & Nemeth, E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 500–510 (2015).

Martins, A. C., Almeida, J. I., Lima, I. S., Kapitão, A. S. & Gozzelino, R. Iron metabolism and the inflammatory response. IUBMB Life 69, 442–450 (2017).

Krismer, B., Weidenmaier, C., Zipperer, A. & Peschel, A. The commensal lifestyle of Staphylococcus aureus and its interactions with the nasal microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 675–687 (2017).

Ayaz, M. et al. Synergistic interactions of phytochemicals with antimicrobial agents: Potential strategy to counteract drug resistance. Chem. Biol. Interact. 308, 294–303 (2019).

Mahomoodally, M. F. & Sadeer, N. B. Antibiotic potentiation of natural products: A promising target to fight pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Drug Targets 22, 555–572 (2020).

Parkinson, E. I. et al. Deoxynybomycins inhibit mutant DNA gyrase and rescue mice infected with fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria. Nat. Commun. 6, 6947 (2015).

King, A. M. et al. Aspergillomarasmine A overcomes metallo-β-lactamase antibiotic resistance. Nature 510, 503–506 (2014).

Park, S. W. et al. Target-based identification of whole-cell active inhibitors of biotin biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 22, 76–86 (2015).

Verma, S. & Prabhakar, Y. S. Target based drug design - a reality in virtual sphere. Curr. Med. Chem. 22, 1603–1630 (2015).

Graef, F. et al. In vitro model of the Gram-negative bacterial cell envelope for investigation of anti-infective permeation kinetics. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 1188–1196 (2018).

Richter, R. et al. A hydrogel-based in vitro assay for the fast prediction of antibiotic accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria. Mater. Today Bio 8, 100084 (2020).

Martin, E. J. et al. All-Assay-Max2 pQSAR: activity predictions as accurate as four-concentration IC50s for 8558 Novartis assays. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59, 4450–4459 (2019).

Durrant, J. D. & Amaro, R. E. Machine-learning techniques applied to antibacterial drug discovery. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 85, 14–21 (2015).

Newman, D. J. & Cragg, G. M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 83, 770–803 (2020). Fundamental review addressing the role of natural products in drug discovery during the past 40 years.

Locey, K. J. & Lennon, J. T. Scaling laws predict global microbial diversity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5970–5975 (2016).

Thompson, L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017).

Mousa, W. K., Athar, B., Merwin, N. J. & Magarvey, N. A. Antibiotics and specialized metabolites from the human microbiota. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 1302–1331 (2017).

Zipperer, A. et al. Human commensals producing a novel antibiotic impair pathogen colonization. Nature 535, 511–516 (2016). Research article describing the discovery of the novel antibiotic lugdunin produced by commensals of the human nasal microbiome.

Imai, Y. et al. A new antibiotic selectively kills Gram-negative pathogens. Nature 576, 459–464 (2019). This study describes the discovery of the new antibiotic darobactin that is active against Gram-negative pathogens.

Adnani, N., Rajski, S. R. & Bugni, T. S. Symbiosis-inspired approaches to antibiotic discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 784–814 (2017).

Lodhi, A. F., Zhang, Y., Adil, M. & Deng, Y. Antibiotic discovery: combining isolation chip (iChip) technology and co-culture technique. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 7333–7341 (2018).

Kealey, C., Creaven, C. A., Murphy, C. D. & Brady, C. B. New approaches to antibiotic discovery. Biotechnol. Lett. 39, 805–817 (2017).

Ling, L. L. et al. A new antibiotic kills pathogens without detectable resistance. Nature 517, 455–459 (2015). An intriguing example of discovering a new antibiotic (teixobactin) from uncultured bacteria by using innovative cultivation techniques (iChip).

Ma, L. et al. Gene-targeted microfluidic cultivation validated by isolation of a gut bacterium listed in Human Microbiome Project’s Most Wanted taxa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9768–9773 (2014).

Mahler, L. et al. Highly parallelized microfluidic droplet cultivation and prioritization on antibiotic producers from complex natural microbial communities. eLife 10, e64774 (2021).

Jiang, C.-Y. et al. High-throughput single-cell cultivation on microfluidic streak plates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 2210–2218 (2016).

Seyedsayamdost, M. R. High-throughput platform for the discovery of elicitors of silent bacterial gene clusters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 7266–7271 (2014).

Pishchany, G. et al. Amycomicin is a potent and specific antibiotic discovered with a targeted interaction screen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10124–10129 (2018).