Abstract

Many of the currently available COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics are not effective against newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 variants. Here, we developed the metallo-enzyme domain of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)—the cellular receptor of SARS-CoV-2—into an IgM-like inhalable molecule (HH-120). HH-120 binds to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike (S) protein with high avidity and confers potent and broad-spectrum neutralization activity against all known SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. HH-120 was developed as an inhaled formulation that achieves appropriate aerodynamic properties for rodent and monkey respiratory system delivery, and we found that early administration of HH-120 by aerosol inhalation significantly reduced viral loads and lung pathology scores in male golden Syrian hamsters infected by the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) and the Delta variant. Our study presents a meaningful advancement in the inhalation delivery of large biologics like HH-120 (molecular weight (MW) ~ 1000 kDa) and demonstrates that HH-120 can serve as an efficacious, safe, and convenient agent against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Finally, given the known role of ACE2 in viral reception, it is conceivable that HH-120 has the potential to be efficacious against additional emergent coronaviruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The vast scale of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the suboptimal protection efficacy for the viral infection after vaccination have provided a fertile ground for the emergence of variants with adaptive advantages, including increased transmissibility and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies targeting SARS-CoV-2’s receptor-binding domain (RBD)1. The currently prevailing Omicron variants harbor more than thirty mutations in the S protein2,3, and are markedly resistant to neutralization by serum from convalescent patients or vaccinated individuals2,3,4. These variants also escape the majority of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies of diverse epitopes2,3,4. Notably, three antibody regimens (Bamlanivimab plus Etesevimab, Casirivimab plus Imdevimab, and Sotrovimab) granted Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) by the FDA for treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in 2021 have now been limited in use for the treatment of infections caused by susceptible SARS-CoV-2 variants (i.e., not for the Omicron variant)5. Two small molecule oral antivirals (Molnupiravir and Paxlovid) granted EUA by the FDA in Dec. 2021 showed clinical benefit in Omicron variant-infected and hospitalized patients not requiring oxygen therapy on admission6. However, each has its own limitations: Molnupiravir has potential host mutagenic risk and can potentially increase SARS-CoV-2 mutation frequencies7,8. Paxlovid (Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir) is contraindicated with drugs for drug-drug interactions owing to Ritonavir’s CYP3A induction effect, limiting its widespread use9. Moreover, a recent study reported that the effect of Paxlovid in patients under 65 is limited10.

Along with the mutation of the virus and the building of the population immunity, the major symptoms of COVID-19 are also evolving, from the severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by the ancestral strains through Delta variant to the more recent mild-to-moderate upper respiratory symptoms caused by the Omicron variant11,12. Nonetheless, the respiratory system remains the major target for the virus. Although SARS-CoV-2 can also infect other organs, this typically only occurs in relatively severe cases or in late-stage COVID-1913. Thus, anti-COVID-19 agents that confer their benefit directly in the upper respiratory tract and lungs, ideally through inhalation, could enable superior clinical efficacy over the systemic delivery route (e.g., intravenous administration) generally used for delivery of monoclonal antibodies or other large biologics, which are transported rather inefficiently to the lungs from circulation (concentration in the lungs is 500–10,000 times lower than that in circulation14).

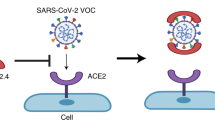

Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is the cellular receptor required for viral entry of SARS-CoV-215,16 and SARS-CoV17,18, as well as all of their known variants and closely related viruses from animals19. ACE2 is a type I transmembrane protein with two extracellular domains, the amino-terminal metallo-enzyme domain and the carboxy-terminal collectrin-like domain (CLD)20,21. The SARS-CoV-2 S protein binds on top of the metallo-enzyme domain (independent of its enzymatic activity)21, after which the virus either undergoes endocytosis (as with Omicron infection)22 or proceeds to direct membrane fusion (with the aid of TMSSP22) in other SARS-CoV-2 infections23. Therefore, unlike neutralizing antibodies, soluble proteins derived from the extracellular domain of human ACE2 (hACE2) can serve as a decoy for preventing the viral binding to the host cell and, notably, are intrinsically resistant to viral mutational escape24.

Recombinant hACE2 proteins—with or without a tag—have been tested for blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection in cell cultures25,26,41. Seeking to maximize the exposure of HH-120 to SARS-CoV-2 viruses to improve its bioavailability, we evaluated whether HH-120 could be administrated via inhalation, which should support direct delivery of HH-120 (with a MW of ~1000 KDa) to the entire respiratory tract from the nose to lung, thus efficiently targeting the SARS-CoV-2 virus locally at the main infection sites. We choose a mesh vibrating nebulizer instrument (Aerogen Solo) that employs a mini pump to produce fine particles with geometric diameter range between 1–5 μm42 (i.e., ideally sized particles for deep lung deposition43). To evaluate the influence of nebulization on the physicochemical properties and neutralization activity of HH-120, HH-120 aerosols produced by the Aerogen Solo instrument were collected and analyzed: HH-120 exhibited the same SEC-HPLC peak profiles before and after nebulization, without notable aggregation or degradation, and the HH-120 main peak maintained at a high percentage level after nebulization (98.78%) as compared to that before nebulization (99.13%) (Supplementary Fig. 3). Moreover, importantly, HH-120 had the same binding avidity (Supplementary Fig. 4) and neutralization activity before and after nebulization (Fig. 4a).

a Pseudotyped virus neutralization analysis of HH-120 before and after nebulization. HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 5 mL of 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution. Data shown are average values of two replicates from distinct samples. b APSD profiles and drug delivery profiles (delivery rate and total drug delivered) after inhalation of HH-120 measured by an NGI and a breathing simulator. Data shown are the ranges of six independent experiments. FPF fine particle fraction, MMAD mass median aerodynamic diameter, GSD geometric standard deviation. c HH-120’s deposition profiling in hamster respiratory tract immediately after the inhalation (n = 2). d Clearance kinetics of inhaled HH-120 in hamster lungs after inhalation at 0, 6, and 24 h after inhalation (n = 2) (left panel). Each curve represents data from one hamster. Body weight-based lung deposited doses, estimated delivered doses and estimated concentration of HH-120 in lung lining fluid (LLF) for the three dose groups are shown in the right panel. * the calculation was based on the estimation of the surface area of mammalian lungs as 1 m2/kg body weight45; ** the delivered dose is about 10-fold of the deposited dose in rodents46, LLF volume for hamsters was estimated as 0.15 mL. e AUC values of 0–5 min (0.0833 h) of inhaled HH-120 in rat lungs after inhalation (n = 6 per group). f Clearance kinetics of inhaled HH-120 in rat nasal cavities, larynxes, tracheas, and lungs after inhalation (n = 6 except n = 4–6 for 48 h timepoint) (left panel), error bars represent the SD. HH-120 amounts deposited in the lungs and estimated concentration of HH-120 in LLF at 0.0833, 6, 12, and 24 h after inhalation are shown in the right panel, LLF volume for rats was estimated as 0.3 mL. g Neutralization activity analysis of HH-120 after inhalation (n = 2/group). Data shown are the mean values (c, e–g). HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 via Aerogen solo nebulizer administered to hamsters using a whole-body inhalation exposure system (c–d) Ancestral D614 strain pseudotyped viruses were used (a, g). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Aerosol droplets ranging from 0.5 to 5 μm in diameter have been reported as the most suitable particle sizes for deposition in small airways and alveoli in humans43. We next characterized HH-120 aerodynamic particle size distribution (APSD) using Next Generation Impactor (NGI), a high-performance cascade impactor. The fine particle fraction (FPF) (≤5 μm) of HH-120 aerosols ranged from 51.97–55.81%, with a mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) of 4.40–4.73 μm and a geometric standard deviation (GSD) of 2.18–2.26 μm (Fig. 4b), values within suitable ranges for lung deposition in both human and rodents43,44. Detailed particle size distribution in different size ranges is presented in Supplementary Table 2. We also used a breathing simulator—an instrument designed to generate and apply an inhalation and/or exhalation profile that mimics a human subject—to assess the drug delivery rate and total drug delivered. In the HH-120 inhalation test, aerosols generated by nebulizing 50 mg HH-120 solution using the Aerogen Solo were delivered at a rate of 0.022–0.034 mg/s, and a total of 17.12–27.48 mg (34.24–54.96%) HH-120 were delivered, indicating that about half of HH-120 aerosols produced by Aerogel Solo could be inhaled by a human.

HH-120 can be effectively deposited in the lungs of hamsters through inhalation

Prior to conducting in vivo efficacy studies, we analyzed the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of aerosolized HH-120 in the respiratory tract of hamsters. Deposition of HH-120 in the respiratory tract was analyzed by measuring HH-120 amount in the ex vivo tissue samples after inhalation. HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution were delivered to hamsters by using a whole-body inhalation exposure system. PK analysis showed that immediately after 50 min of HH-120 inhalation, about 80.22%, 17.33%, and 2.45% of inhaled HH-120 was deposited in the lung, nasal cavity, and trachea of the animals, respectively (Fig. 4c). These results support that the majority of the aerosolized HH-120 was deposited in the lungs after inhalation.

Further testing of the lung PK profile of inhaled HH-120 in three dose groups (5-min, 15-min, and 50-min inhalation of HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution) in hamsters showed that the deposited HH-120 in the lungs was cleared after inhalation, with a half-life of about 6 h across the three dose tested groups (Fig. 4d left panel). The lung delivered doses and deposited doses were estimated. Immediately after 5-min, 15-min, and 50-min inhalation of HH-120 aerosols, total HH-120 depositions per lung were 1.68, 5.18, and 18.46 μg, respectively. According to the estimation of the surface area of mammalian lungs as 1 m2/kg body weight45, and a body weight of about 120 g per hamster, the body weight-based lung deposited doses of HH-120 for the three different inhalation duration groups were calculated as ~0.014, 0.043, and 0.154 mg/kg, respectively. Given that the deposited dose for rodents is about 10% of the delivered dose46, the delivered doses thus can be estimated as ~0.14, 0.43, and 1.54 mg/kg, respectively (Fig. 4d right panel).

According to the estimation of the volume of lung lining fluid (LLF) in the literature for different species (e.g., for humans the LLF volume ranging ~15–70 mL)47,48, and considering species differences in lung surface area and body weight47, the LLF volume for hamsters can be estimated as half of that of rats (0.1–0.3 mL), in a range of ~0.05–0.15 mL. Take the high-end estimation of 0.15 mL into calculation, the HH-120’s LLF concentrations in hamsters for the delivered doses of 0.14, 0.43, and 1.54 mg/kg can be estimated as ~11.20 μg/mL, 34.50 μg/mL and 123.10 μg/mL, respectively (Fig. 4d right panel). Recall the in vitro IC90s for authentic viruses are 120–1176 ng/mL (Fig. 3b), thus even the lowest delivered dose (0.14 mg/kg) in hamsters can provide at least 10-fold higher local HH-120 concentration than the highest IC90.

The PK profile of inhaled HH-120 was further evaluated in SD rats with 29 rats (14–15/sex) in each target delivered dose. HH-120 was given via an inhalation exposure system which was connected to Aerogen Solo nebulizer systems at target delivered dose levels of 5 and 15 mg/kg/dose corresponding to actual delivered doses of 4.127 and 15.000 mg/kg/dose. Blood serum samples, larynx, trachea, and lung tissues of the rats, as well as the nasal lavage fluid (NLF) were collected separately at 0 (<5 min), 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after the completion of a single dose of HH-120 inhalation (n = 6 except n = 4–6 for the 48 h timepoint). HH-120 was undetectable in serum samples using a validated ELISA assay. Consistent with the results obtained from hamsters described above, the HH-120 deposited in the lungs after inhalation was cleared with a half-life of about 8 h and it was cleared faster in other regions of the respiratory tract (Fig. 4e, f). The Cmax of HH-120 in the lung tissues increased in an approximately dose-proportional manner (Fig. 4f left panel). Based on the surface area for mammalian lungs (~1 m2/kg body weight)45, and about 230 g average body weight for the rats used in this study, the body weight-based lung deposited dose of HH-120 at Cmax is ~0.19 mg/kg and 0.69 mg/kg for the target delivered doses of 5 and 15 mg/kg, respectively. Tmax was the first sampling timepoint (5 min) for all the dose group animals.

According to the previously described LLF volume estimation for rats (~0.1–0.3 mL), and take the high-end estimation of 0.3 mL into calculation, the HH-120’s LLF concentrations in rats can be estimated as 50.60 μg/mL and 17.27 μg/mL at 12 h and 24 h post administration (5 mg/kg target delivered dose), respectively; 214.43 μg/mL and 110.47 μg/mL at 12 h and 24 h post administration (15 mg/kg target delivered dose), respectively (Fig. 4f right panel). These results indicate that 5 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg doses in rats can respectively provide ~15-fold and ~94-fold higher local HH-120 concentration at 24 h post inhalation than the highest in vitro IC90 (1176 ng/mL) (Fig. 3b).

To evaluate whether HH-120 deposited in hamsters’ lungs can indeed exert viral neutralizing activity, we collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from hamsters after inhalation and evaluated its neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped viruses (ancestral D614 strain). At different time points after HH-120 inhalation (15 min or 30 min, with HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution), the neutralization activity of BALF collected at 12 h after 15 min or 30 min inhalation remained highly potent, achieving >90% neutralization of viral infection at a fourfold dilution (Fig. 4g). These results are consistent with the prediction based on in vitro IC90 values and PK results in rats and hamsters, further support that aerosolized HH-120 can be effectively deposited and exert neutralizing activity in the lungs of hamsters. Choosing a treatment regime of 15 min inhalation of HH-120 (nebulized from 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution) at a dosing frequency of twice daily (BID, every 12 h) should be suitable for in vivo efficacy studies.

HH-120 inhalation shows potent efficacy in hamsters

In vivo efficacy of HH-120 was evaluated using a SARS-CoV-2 hamster infection model. The golden Syrian hamster is an appropriate animal model for testing the efficacy of vaccines or other anti-viral agents against SARS-CoV-2, as hamster ACE2 has been shown to bind to the S protein and to mediate SARS-CoV-2 entry49. Infection with SARS-CoV-2 in hamsters resembles mild-to-moderate disease of COVID-1950, or severe disease of COVID-19 when challenged with high virus doses51; however, infected hamsters typically recover after two weeks of infection50. Experimentally infected hamsters show significant weight loss and similar histopathological manifestations as human COVID-19 pneumonia50,52, displaying focal diffuse alveolar destruction, consolidation, inflammatory cells infiltration in the lungs; the infected hamster respiratory tract permits robust virus replication, with viral titers known to peak around 3 days after infection52.

For the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) infection model, hamsters were challenged intranasally with 1 × 105 pfu of SARS-CoV-2. HH-120 aerosol inhalation began at 2 h post infection, BID for 3 days (Fig. 5a). As described above, 15 min inhalation of HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution was chosen as the inhalation dose. This dose resulted in a ~0.05 mg/kg lung deposited dose of HH-120 (Fig. 4d). After 3 days of BID treatment with HH-120 at 0.5 mg/kg delivered dose, hamsters were euthanatized, the anti-viral efficacy of HH-120 was evaluated by quantifying viral replication (gRNA and sgRNA) in the lungs using qRT-PCR. HH-120 significantly reduced the viral loads indicated by both gRNA and sgRNA in the lungs of all hamsters by about 3 orders of magnitude as compared to untreated hamsters (Fig. 5b), and sgRNA decreased to below the limit of detection in 4 of 7 hamsters. No significant weight change was observed in the treatment group (Fig. 5b).

a Schematic illustration of the virus challenge experimental design. In ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) infection study, two groups of hamsters (n = 7/group) were challenged intranasally with 105 pfu viruses. 2 h post viral challenge, one group of hamsters was given a theoretical delivered dose of ~0.5 mg/kg HH-120; the other group with no treatment served as a control group. In Delta variant infection study, three groups of male hamsters (n = 5/group) were infected with 104 pfu of viruses. Two groups (2 h or 6 h post infection) of hamsters were given a theoretical delivered dose of ~2 mg/kg; the other group was given a placebo inhalation at 6 h post infection and served as a control group. b The therapeutic efficacy of inhaled HH-120 in treating hamsters infected with ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) SARS-CoV-2 (n = 7/group). At the end of treatment, hamsters were euthanatized, the lungs were collected, viral gRNA and sgRNA were measured by qRT-PCR. Relative weight change was assessed at the endpoint of the study. Horizontal lines represent mean values. c The therapeutic efficacy of inhaled HH-120 in treating hamsters infected with Delta SARS-CoV-2 (n = 5/group). The body weight was measured BID. Left lung lobes were collected after hamsters were euthanatized, viral gRNA and sgRNA were quantified by qRT-PCR, the TCID50 value was measured in a Vero cell infection experiment. d Pathology evaluation in Delta variant infection study. The right lungs were collected for H&E staining. Representative images of H&E staining are shown (left). Histopathological changes included mononuclear cells infiltration (blank arrow), hemorrhage (red triangle), widened alveolar septum (blue arrow). Pathological score (right) was obtained by evaluation of about 5 microscopic fields in one H&E staining slide. Error bars represent the SEM in panels (b) and (c) (Weight change). Horizontal lines represent median in panels (c) (gRNA, sgRNA, TCID50 viral titers) and (d) (pathological score). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-sided unpaired Student’s t tests (b–d). *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant infection model, we increased the dose of HH-120 inhalation and lowered the challenge dose of the virus because Delta virus infection was more severe than that of ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) in hamster models, lowering the challenge dose can prevent premature death53. hamsters were challenged intranasally with 1 × 104 pfu of the viruses. A fourfold higher delivered dose (~2 mg/kg) of HH-120 than that used in the ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) infection model was used in this experiment. This delivered dose was achieved by inhalation of HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution for 15 min using two nebulizers in parallel. Buffer control aerosols generated in the same conditions were used as the vehicle group. HH-120 inhalation began at 2 h or 6 h post infection, and the treatment duration lasted for 3 days with a BID inhalation of 15 min each time (Fig. 5a). The weight of hamsters was measured BID. After 3 days of treatment, hamsters were euthanatized, the left lung lobes were collected for viral load analysis, viral gRNA and sgRNA were measured by qRT-PCR, and the TCID50 value was measured using Vero cell infection assays; the right lung lobes were collected for pathological analysis.

With HH-120 treatment, the infection-caused weight loss was clearly attenuated (Fig. 5c). Moreover, HH-120 inhalation significantly reduced the viral loads of gRNA and sgRNA in the hamster lungs by a median of about 3 orders of magnitude in both animal groups treated at 2 h or 6 h post viral challenge. The infectious viral titer (TCID50) in the lung lysates of HH-120 treatment group were also reduced by ~3 logs as compared to the vehicle group (Fig. 5c). The histopathological analysis showed that at 3 days post Delta variant infection, hamsters in vehicle group developed pulmonary damage, including hemorrhage, alveolar wall thickening, and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lungs. HH-120 inhalation at both 2 h and 6 h post viral challenge attenuated pulmonary injury, with the pathological scores significantly lower than those of the vehicle group (Fig. 5d). These results demonstrate that HH-120 inhalation can greatly reduce viral loads in the lung and decrease viral infection-induced pathological damage when administered early after viral infection of the animals, warranting its further clinical development.

HH-120 is safe in non-clinical toxicity studies

To evaluate the safety of HH-120 inhalation, we conducted repeat-dose inhalation toxicity studies in SD rats and cynomolgus monkeys following Good Laboratory Practice (GLP). In the SD rat study, HH-120 was given at target delivered dose levels of 5 and 15 mg/kg/dose BID, corresponding to actual delivered doses of 4.884 and 17.178 mg/kg/dose BID. In the monkey study, HH-120 was given at target delivered dose levels of 2.5 and 8 mg/kg/dose BID, corresponding to actual delivered doses of 2.831 and 9.202 mg/kg/dose BID. For both the rat and the monkey studies, HH-120 was given via an inhalation exposure system that was connected to Aerogen Solo nebulizer systems for two consecutive weeks, followed by a 2-week recovery period. Aerosol samples were collected simultaneously during the toxicity studies for aerosol particle size measurements using NGI. The MMAD range was determined to be 2.82–3.13 μm in the rat toxicity study and 3.38–3.60 μm in the monkey toxicity study. These particle size ranges were found to be appropriate for efficient delivery to both rat and monkey respiratory system44,54. All animals were evaluated for toxicological parameters, including clinical signs, vital functions body weight, food consumption, laboratory tests (hematology, coagulation, clinical chemistry parameters, urinalysis, cytokines, T lymphocyte subsets), organ weight, gross anatomy, and histopathology.

HH-120 inhalation was well tolerated in both SD rats (Fig. 6a–d; Supplementary Tables 3–4) and cynomolgus monkeys (Fig. 6e–h; Supplementary Tables 3, 5) in the repeat-dose toxicity studies described above. In particular, HH-120 inhalation showed no adverse effects on body weight (Fig. 6a, e) and respiratory function (tidal volume and respiratory rate) for both rats and monkeys (Fig. 6b–c, f–g) during both the dosing and the recovery phases. No HH-120-realted adverse effects were observed on the percentage of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets (Fig. 6d, h), and serum levels of cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4 in rats and TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6 in monkeys) for rats (only measured at the endpoints of dosing and recovery phases) and for monkeys (both dosing and recovery phases) (Supplementary Table 3).

a–d Body weight (a), respiratory function (b–c), and T lymphocyte subset percentage changes (d) in two-week repeated dose toxicology study in rats. Four groups of SD rats (15/sex/group) were BID given fresh air, HH-120 formulation buffer or HH-120 at target delivered dose levels of 5 or 15 mg/kg/dose for 14 consecutive days followed by a two-week recovery period. 10/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of dosing period (D16) and 5/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of recovery period (D29). Tidal volume and respiratory frequency were detected by a rat WBP pulmonary system (b–c). Blood samples were collected on D16 and D29 from all euthanasia animals, CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets were analyzed by Flow Cytometry (d). e–h Body weight (e), respiratory function (f, g), and T lymphocyte subset changes (h) in two-week repeated dose toxicology study in monkeys. Three groups of cynomolgus monkey (5/sex/group) were BID given fresh air or HH-120 at target delivered dose levels of 2.5 or 8 mg/kg/dose for 14 consecutive days followed by a two-week recovery period. 3/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of dosing period (D15) and 2/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of recovery period (D29). Tidal volume and respiratory frequency were detected by a EMKA Non-invasive physiological signal telemetry system at the indicated timepoints post first dose at the indicated days (f, g). Blood samples were collected on five or six days before dose initiation, on D8, at the end of dosing (D15), and at the end of recovery period (D29), CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets were analyzed by Flow Cytometry (h). Data shown are the mean values (a–h). Error bars represent the SD (a–h). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the rat toxicity study, the histopathological findings were minimal, sporadic, and unrelated to HH-120 (Supplementary Table 4). The no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL) was determined to be 17.178 mg/kg/dose (target delivered dose group of 15 mg/kg/dose) BID, which is ~30-fold higher than its effective delivered dose (~0.5 mg/kg/dose) tested in the hamster model.

In the monkey toxicity study, the major histopathological findings were limited to histological alterations in lungs: slight-to-moderate mononuclear cell infiltration in the perivascular region and interstitium of lungs in animals from both the 2.5 and the 8 mg/kg/dose groups, which was fully recovered by the end of two-week recovery period (Supplementary Table 5). Similar histological alterations in lungs were commonly observed in inhalation safety studies, which likely result from a local cleansing response mediated by immune systems55. Therefore, the observed mononuclear cell infiltration in lungs of animals from HH-120 dose groups was considered as a non-adverse effect, which is related to inhalation of macromolecule drug class rather than HH-120 specific. The NOAEL was determined to be 9.202 mg/kg/dose (target delivered dose group of 8 mg/kg/dose) BID. All these pre-clinical animal studies support a good safety profile for HH-120.

Discussion

The ongoing emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants has caused considerable concerns related to increased breakthrough infections after vaccination and escape from neutralizing antibody therapeutics56; it is therefore critical for public health efforts to continue the development of technologies to prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infections. It bears repeating that all known emerging SARS-CoV-2 viruses use hACE2 as the primary receptor, supporting the particular utility of develo** hACE2-derived molecules as entry blockers that can confer broad-spectrum activities against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 infections24,57. The Omicron variant of SARS- CoV-2 offers an interesting case-in-point: this variant became more transmissible by increasing its affinity to hACE258,59, so an hACE2-mimic recombinant protein that is potent and inherently resistant to viral escape would be assumed as a likely effective agent against the infection. However, a study reported that a bivalent hACE2-Fc fusion protein showed low neutralization activity to ancestral SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped virus with an IC50 of 3.03 μg/mL26, and hACE2-hIgG1 (similarly a bivalent ACE2 with an Fc tag of hIgG1) in our study showed low activity as well in neutralizing authentic SARS-CoV-2 ancestral viruses, with an IC50 of 5.3 μg/mL. These findings together indicate that bivalent hACE2 lacks sufficient potency and therefore may has limited clinical application potential.

In the present study, we used an IgM-like design that enabled the gain of potency in neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 through increased avidity. Indeed, HH-120 confers about a hundred-fold higher neutralization activity than the Fc-tagged bivalent hACE2 (ACE2-hIgG1), which is comparable to EUA-issued monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants prior to Omicron60,61. HH-120 is superior to most reported monoclonal antibodies in neutralizing the Omicron variant3 (with single-digit ng/mL IC50 values) in pseudotyped virus neutralization assays, although no side-by-side comparison has yet been conducted. Considering the broad-spectrum activity of HH-120 and its superior potency, it holds promising potential to be translated in humans as an effective agent for both prophylactics and early treatment of COVID-19.

A drug candidate named APN01, a soluble recombinant form of rhACE2, is currently under evaluation as a treatment (via infusion injection) for COVID-19. An earlier completed phase 2 trial (NCT04335136) with intravenously administered APN01 showed ambiguous efficacy in disease control for the treatment of hospitalized cases of COVID-19. A clinical trial for inhaled APN01 (NCT05065645) to assess safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics was launched in Oct. 2021. Although the efficacy of APN01 against SARS-COV-2 remains to be tested, these clinical trials provide favorable safety evidence for use of ACE2-derived agents. ACE2 can catalyze the hydrolysis of angiotensin II into angiotensin and functions as a regulator in renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)62. Angiotensin II levels decreased rapidly following infusion of APN01, whereas angiotensin-(1–7) and angiotensin-(1–5) levels increased and remained elevated for 48 h in a phase 2 trial of APN01 (NCT01597635)63. Distinct from APN01, the enzymatic activity of hACE2 is deactivated in HH-120, eliminating the possibility of interfering with RAAS by the exogenous hACE2. Although a study indicates catalytic activity of ACE2 may slightly contribute to therapeutic efficacy for SARS-CoV-2 infection64, some ACE2 decoys are also designed to remove the catalytic activity for safety considerations24,30. Moreover, HH-120 does not contain the collectrin-like domain of hACE2, which mediates homodimerization of hACE221. This simplifies protein engineering and purification of HH-120 and reduces the risk posed by soluble hACE2-mediated infection enhancement of SARS-CoV-265.

Drug delivery through inhalation can be used for local and/or systemic action, depending on the ability of the aerosolized drug to cross the air-blood barrier. It is known that the diffusion of large therapeutics between the bloodstream and alveoli is limited, because the respiratory tract epithelium constitutes a barrier to the transport of large macromolecules (that do not diffuse passively through tight junctions)14,66. Given HH-120’s MW of nearly 1000 kDa, it was unsurprising when we observed no systemic drug exposure in rats or monkeys in our repeat-dose inhalation studies. Our detailed local PK profiling work in hamsters and rats and a comprehensive in vitro IC90 determination for various authentic viruses also help to provide basis for making extrapolations and predictions for dose selection and dosing frequency in future human studies. Beyond showing improved bioavailability of the drug and deceased potential for systemic side effects, our local delivery of aerosolized HH-120 to the respiratory tract in the COVID-19 context illustrates an attractive alternative administration route that is likely relevant to many future therapeutics.

In the present study, we demonstrated the local delivery of HH-120 by inhalation significantly reduced viral loads in the lung and decreased viral infection-induced pathological damage when administered early at 2 h or 6 h post-infection, supporting further clinical development of HH-120 for early treatment to prevent disease progression in humans. Nonetheless, the full therapeutic potential of HH-120 inhalation remains to be explored, testing at later timepoints post-infection (e.g. 12, 24 or 48 h) in animal models will help addressing whether HH-120 inhalation can be used for treating COVID-19 at a relatively late infection stage.

Since early 2022, the Omicron variant with high transmissibility and immune evasion ability has replaced Delta as the dominant variant. As the Omicron variant usually leads to upper respiratory system infection, it would be important to recalibrate the potential clinical benefit of the HH-120 inhalation in the Omicron era. Instead of reduction of hospitalizations or death from COVID-19, early use of HH-120 is likely more suitable for improving acute upper respiratory symptoms and post exposure prophylaxis through direct delivery to the upper respiratory tract (e.g. by nasal spray of the inhalable HH-120). Testing HH-120 being administered as soon as contracting or having had high-risk exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection has been prioritized in clinical trials, a phase 2 (NCT05713318) clinical trial for early treatment and a phase 3 clinical trial (NCT05787418) for post-exposure prophylaxis are currently ongoing.

Methods

Protein expression

hACE2-hIgG1 was constructed by fusing the extracellular domain of human ACE2 (amino acid 19–615) (UniProt Q9BYF1) to the human IgG1 hinge and Fc (UniProt P01857). H374N and H378N mutations were introduced to inactivate the Zinc metallo-enzyme activity17. HH-120 was constructed by fusing hACE2-hIgG1 with an IgM tailpiece (PTLYNVSLVMSDTAGTCY)33. hACE2-hACE2-hIgG1 was constructed by tandemly fusing two hACE2 proteins to the N terminus of hIgG1. hACE2-hIgG1-hACE2 was constructed by fusing hACE2 to the N terminus and the C terminus of hIgG1. AbCR3022-hACE2 and Ab1-hACE2 were constructed by fusing hACE2 to the C terminus of CR3022 and Ab1. AbCR3022 is a monoclonal antibody with cross-binding activity to both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV67. Ab1 is a SARS-CoV-2 neutralization antibody developed in our lab. The coding sequences of the proteins were cloned into a pCAGGS vector or a pKS001 vector, and the proteins were produced in 293F cells (ThermoFisher)68 or CHO-K1Q cells (QuaCell) by either transient transfection or establishing stable cell lines. Cell cultures were harvested at a cell density of 1–2×107/mL for next purification steps.

SARS-CoV-2 RBD binding affinity and avidity analyses

SPR (BIAcore T200) and Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) (Fortebio Octet RED384) technologies were applied to measure the binding affinity and avidity of HH-120 and its bivalent form (hACE2-hIgG1) to SARS-CoV-2 RBD (amino acids 316-512 of the S protien in the SARS-CoV-2 D614 strain) or S trimer proteins of the Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron variants (Sino Biological).

For affinity testing, the hACE2-hIgG1 or HH-120 was captured on the surface of a CM5 biosensor chip (Cytiva) coupled with an anti-human Fc antibody (Cytiva), twofold serially diluted SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins or S trimer proteins of Alpha, Beta, Delta, Omicron variants (from 200 to 6.25 nM) in HBS-ET buffer were flowed through the chip at a speed of 30 μL/min, the binding constant (Ka), dissociation constant (Kd), and equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) were calculated using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model (BIA Evaluation software). For avidity testing, 20 μg/mL SARS-CoV-2 RBD proteins bearing His-avi tag were captured on the surface of a streptavidin biosensor (Sartorius, Octet), 2-fold serially diluted hACE2-hIgG1 (52.6–1.65 nM) or HH-120 (263.2–8.22 nM) were bound to the surface of the RBD-captured sensor for 180 s, and then dissociated for 300 s. A 1:1 binding model (Fortebio data Analysis 11.1-kinetics software) was used to calculate binding constants (Ka, Kd, and KD).

Single-particle negative-stain EM

For negative-stain EM, purified HH-120 (3 μL of 0.12 mg/mL) was applied to a glow-discharged carbon coated copper grid for 45 s and was then blotted off with filter paper. The grid was washed using washing buffer (25 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 100 mmol/L Arg-HCl, pH7.5), and then immediately stained using 2% uranyl acetate solution. Data were acquired on a Talos L120C electron microscope operated at 120 kV equipped with an FEI Ceta 4 K detector. Images were collected at a pixel size of 3.122. Data processing including micrograph screening, particle picking, particle selection. 2D reconstruction were performed using CryoSparc v3.3. Patch CTF estimation was used to check the defocus (−1 to −3 μm) and max resolution of all micrographs. Several rounds of 2D classifications were performed to remove poor-quality particles and about 25,343 high-quality particles were picked for final HH-120 2D model construction.

ADCC and ADCP reporter assays

Jurkat/NFAT-luc2p/FcγRIIa, Jurkat/NFAT-luc2p/ FcγRIIIa cell lines, CHO cells stably expressing SARS-CoV-2 S protein (CHO-S) established in-house were employed as effector cells and target cells, respectively. CHO-S cells (15,000 cells/well) were seeded in a white, flat bottom, opaque 96-well plate and cultured for 16–20 h at 37 °C, followed by brief incubation with serially diluted HH-120. The effector cells were then added at an effector-to-target cell ratio (E:T) of 6:1. Luciferase activities were measured using a Bright-GloTM Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a Centro LB 960 Microplate Luminometer (Berthold).

Pseudovirus neutralization assay

Plasmids encoding S proteins of Pangolin-CoV, SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 D614, G614, G614 variants bearing single-site mutations (L18F, A222V, V367F, K417N, N439K, L452R, Y453F, S477N, S477I, T478A, T478I, E484K, F486L, N501Y, A520S, P1263L), Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Epsilon (B.1.427/429), Gamma (P.1), Kappa (B.1.617.1), Delta (B.1.617.2), and Omicron (B.1.1.529, BA.1.1, BA.2, BA2.12.1, BA.4 or BA.5, BA.2.75, BA.2.76, BF.7, XBB, BQ.1.1) variants were constructed respectively. SARS-CoV-2 pseudotyped viruses were produced using a lentivirus system69 (prepared in house) or a VSV system70 (Vazyme #DD1201). For lentivirus system based pseudotyped virus preparation, 293 T cells were co-transfected with S protein expression plasmid, a lentiviral packaging plasmid, and a plasmid harboring a firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter gene (1:3:4). Viral supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection. Viral titers were measured as luciferase activity (using relative light units; Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System).

Neutralization assays were performed using the 293T-ACE2 stable cell line. Pseudotyped viruses were incubated with serially diluted HH-120 at room temperature for 30 min. The mixtures were then added to 96-well plates that had been seeded with 1.0 × 105 (lentivirus system) or 8.0 × 104 (VSV system) 293T-ACE2 cells/well one day prior to infection. After a 24 h incubation, the cells were washed and further incubated for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured on a Centro LB 960 Microplate Luminometer (Berthold) or an EnVision 2105 Multimode Plate Reader (PerkinElmer) using a Bright-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). The percentages of infectivity were calculated as the ratio of luciferase readout in the presence of HH-120 normalized to the luciferase readout of PBS controls. The IC50 values were determined using 4-parameter logistic regression (GraphPad Prism). Cells without viral infection were used as blank controls.

Authentic live virus neutralization assay

Neutralization assays were performed under biosafety level-3 (BSL-3) conditions. Neutralization activity of HH-120 or hACE2-hIgG1 against SARS-CoV-2 prototype strain (EPI_ISL_402119) was analyzed using Vero cells as host cells, and the assay was performed as described previously71 at the National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC. Briefly, Vero cells were seeded in a 96-well plate with 2.0 × 104 cells/well and incubated at 37 °C one day prior to virus infection. Viruses at titer of 200 TCID50 were mixed with serial diluted HH-120 or hACE2-hIgG1 respectively, incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, added the mixture to Vero cells. After 48 h incubation, Cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed, and 100 μL of the culture supernatant was harvested for qRT-PCR analysis. TCID50 of the virus in the sample was calculated according to the CT value of the sample and a standard curve. The neutralization potency was calculated as follows: Inhibition % = (TCID50 without drug—TCID50 with drug)/ TCID50 without drug ×100%. The ancestral strain (GISAID accession: EPI_ISL_402119) was isolated from a SARS-CoV-2 infected patient by China CDC.

HH-120’s neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27), Alpha, Beta, Delta, Omicron (XBB.1.16) variants was analyzed using Vero cells as host cells, and the assay was performed as described previously72 at National Kunming High-level Biosafety Primate Research Center, Yunnan. Briefly, Vero host cells (4.0 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C one day prior to virus infection. Then, the Vero cells were pre-treated with different doses of HH-120 for 1 h, and the virus (multiplicity of infection (MOI) = 0.05) was subsequently added to allow infection for 1 h. At 48 h post infection, CPEs were observed and viral yield in the cell supernatant was then quantified by qRT-PCR. The ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) was from Guangdong CDC, China.

HH-120’s neutralization activity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) was analyzed using HK-2 cells as host cells, and the assay was performed as described previously73 at the Carol Yu Centre for Infection of the University of Hong Kong. Briefly, HH-120 was serially diluted in 5-fold starting from 10 μg/mL. Duplicates of each sample were mixed with 100 TCID50 of Omicron variant (B.1.1.529) for 1 h, and the HH-120 virus mixture was then added to HK-2 cells. After incubation for 3 days, CPE was examined. For all the authentic virus neutralization assays, the IC50 values were determined using 4-parameter logistic regression. Cells without viral infection were used as blank controls.

SARS-CoV-2 S protein mediated syncytia formation assay

293T cells co-transfected with plasmids expressing the SARS-CoV-2 S protein and pEGFP-N1 were termed “S cells”, while 293T cells co-transfected with plasmids expressing hACE2-C9 and pmCherry-C1 were termed “ACE2 cells”. 24 h after transfection, both the S cells and ACE2 cells were digested with EDTA and washed once with DMEM complete medium. The S cells were then pre-incubated with the HH-120 or hACE2-hIgG1 at 37 °C for 30 min before being co-cultured with the ACE2 cells at a cell ratio of 1:1. After another 3 h or 20 h of co-culture, S-ACE2 interaction-mediated syncytia formation (assessed as the mergers of green and red cells) was imaged under a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti, NIKON). 293T cells transfected with the EGFP plasmid alone co-culturing with ACE2 cells were used as a mock control. DMEM completed medium without drug were used as a negative control (blank).

Aerodynamic assessment of HH-120 nebulized using a mesh vibrating nebulizer

APSD profiles were measured by an NGI (Model 170, COPLEY) in accordance with the instructions. Briefly, an NGI was connected to a flow meter and a vacuum source generating a 15 L/min inlet flow rate. The NGI inlet nozzle was connected to an Aerogen Solo nebulizer through an adaptor. The cut-off diameters for the stage 1 to stage 7 of NGI at volumetric flow rate of 15 L/min were 14.1, 8.61, 5.39, 3.30, 2.08, 1.36, and 0.98 μm, respectively. HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution for 8 min. The average nebulized volume was about 2 mL in 6 independent experiments. HH-120 deposited on the nebulizer, mouthpiece adaptor (MA), induction port (IP), and 7 stages of NGI was washed off by HH-120 formulation buffer. Collected HH-120 was quantified by SEC-HPLC. FPF%, MMAD, GSD were determined using Copley Inhaler Testing Data Analysis Software (CITDAS). Drug delivery rate and total drug delivered were measured by breathing simulator (BRS1100, COPLEY) in accordance with the instructions. Briefly, breathing simulator was set at the adult pattern with tidal volume of 500 mL, breath frequency of 15 times/min, sinusoidal waveform, Inhalation/Exhalation (I:E) Ratio of 1:1. An Aerogen Solo nebulizer was connected to a breathing simulator through an adaptor. HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 5 mL of 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution. HH-120 deposited on the filter membrane (COPLEY) which reflects total drug delivered was washed off by blank solvent and quantified by SEC-HPLC. The delivery rate was calculated as total drug delivered divided by nebulization time.

Respiratory tract deposition assay in hamsters via aerosol inhalation

The animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Bei**g. Male or female (6–8 w of age), specific-pathogen-free golden Syrian hamsters (Hebei Invivo Biotech Co. Ltd.) were used. HH-120 inhalation was delivered to hamsters using a small animal whole-body inhalation exposure system customized by Yuyan Instruments Inc., which is comprised an air pump, a mass flowmeter, and an exposure box. The exposure box, which can accommodate at least 8 hamsters, can be interfaced with the adapter of a Aerogen Solo nebulizer. HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution using the Aerogen Solo nebulizer. For hamster respiratory tract deposition profile characterization, immediately after 50 min of HH-120 inhalation, two hamsters per group were euthanized, NLF was collected through entire nasal cavity lavage with 0.9% saline, and the trachea, bronchus, and lung tissues were harvested and digested in RIPA lysis buffer. For testing of the lung PK profile of inhaled HH-120, three groups of hamsters (n = 6/group) were given a single dose (5-min, 15-min, or 50-min) inhalation of HH-120 aerosols. At different time points (0, 6 and 24 h) after the end of inhalation, two hamsters of each group at each time point were euthanized and lungs were collected. For neutralization activity analysis of BALF, two groups of hamsters (n = 4/group) were given a single dose (15-min or 30-min) inhalation of HH-120 aerosols. Immediately (0 h) and 12 h after inhalation, two hamsters of each group at each time point were euthanized and BALF was collected from the euthanized hamsters. Serially diluted BALF samples were then analyzed for neutralization activities against pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 viruses (D614). The amount of HH-120 in serum, lavage, and lysate were determined using RBD capture ELISA with a standard HH-120 sample.

PK evaluation of inhaled HH-120 in SD rats

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of JOINN Laboratories, China. Male or female, specific-pathogen-free SD rat (6–8 w of age) (Zhejiang Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.) were used. HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution and were given via an inhalation exposure system connected to four Aerogen Solo nebulizer systems. The delivered dose was calculated using the formula: Delivered dose (mg/kg) = RMV × Ec × T/BW74. RMV (L/min) = Respiratory Minute Volume = 0.608 × BW (kg)0.852; Ec (mg/L air) = Concentration delivered to the animals; T (min) = Duration of exposure; BW (kg) = Body weight. Before dosing, the target delivered dose was calculated using the above formula with Ec = Estimated delivery concentration deduced from previous tests for measuring aerosolized HH-120 convention by filter sampling method; after dosing, the actual delivered dose was calculated using the same formula with Ec = actual concentration directly measured by filter sampling during the PK study. A total of 58 SD rats were randomly assigned to two groups (14–15/sex/group) and given HH-120 at target-delivered doses of 5 or 15 mg/kg/dose. At 0 (<5 min), 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after completion of a single dose of HH-120 inhalation (n = 3/sex except n = 2–3/sex for 48 h timepoint), rats were euthanized and blood serum samples, nasal lavage fluid (NLF), and larynx, trachea, and lung tissues of the rats were collected separately. The amount of HH-120 in serum, lavage, and tissues lysates were measured using RBD capture ELISA.

RBD capture ELISA

2 μg/mL biotin-labeled COVID-19 RBDs were captured on a 96-well plate that was pre-coated with 2 μg/mL streptavidin. Purified HH-120 or diluted samples (NLF, BALF, or tissue lysate supernatants) were added to the plate; HRP-labeled goat anti-hFc secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher, Pierce) was used as the detection antibody. The optical density (OD) was measured at OD450—OD630 (BioTek).

SEC-HPLC

Purified HH-120, hACE2-hIgG1, or HH-120 washed off in the aerosol assessment assays were analyzed via SEC-HPLC using a TSKgel G4000SWxl analytical column (Tosoh) with an Agilent 1260 HPLC system. 100 μg of HH-120 or hACE2-hIgG1 (in 50 mM PB, 300 mM NaCl at pH 6.7 ± 0.1 buffer) was injected to the system at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min.

SEC-MALS

The system consisted of an Agilent 1200 HPLC system, a DAWN MALS detector (Wyatt Technology), an Optilab differential Refractive Index (dRI) detector (Wyatt Technology), and a TSKgel G4000SWxl analytical column (Tosoh). PBS was used as the running buffer with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. Data acquisition was performed using Astra software (Wyatt Technology).

SV-AUC

SV-AUC experiments were carried out using a 12-mm charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces (Beckman, 392778) and a four-hole An60 Ti rotor at 30,000 rpm (Optima AUC analytical-ultracentrifuge, Beckman Coulter) with absorbance detection at 280 nm at 20 °C. The data were analyzed with SEDFIT software to obtain sedimentation coefficient distribution C (S)75.

Hamster efficacy study of HH-120 inhalation

The animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science and were performed in the animal biosafety level 3/4 (ABSL-3/4) facility of the National Kunming High-level Biosafety Primate Research Center, Yunnan, China. Male (6–8 w of age), specific-pathogen-free golden Syrian hamsters (Hebei Invivo Biotech Co. Ltd.) were used. All hamsters were provided access to standard pelleted feed and water ad libitum for 1 week of acclimatization after arrival. Prior to being moved into the ABSL facility for experimental challenge, hamsters were housed individually in isolated ventilation cages.

For the SARS-CoV-2 ancestral strain (GDPCC-nCoV27) infection model, hamsters were infected with 105 pfu of the viruses intranasally and subsequently exposed for 15 min of HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 5 mg/mL HH-120 solution using the Aerogen Solo nebulizer at 2 h post-infection. Animals were assigned to two groups: control group with no aerosol inhalation treatment (n = 7), and 15 min exposure to HH-120 aerosols BID (n = 7), for a total of 6 exposures.

For the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant infection model, hamsters were challenged intranasally with 104 pfu of the viruses and subsequently exposed for 15 min of HH-120 formulation buffer (placebo control) or HH-120 aerosols generated by nebulizing 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution using two Aerogen Solo nebulizers in parallel at 2 h or 6 h post-infection (n = 5) for a total of 6 exposures.

Baseline body weights were measured for all hamsters before viral challenges and monitored BID after HH-120 inhalation. The hamsters were monitored BID for signs of COVID-19 disease (ruffled fur, hunched posture, labored breathing, anorexia, lethargy) post-challenge with SARS-CoV-2. At necropsy, the left lung lobes were collected for viral load quantification. In the Delta variant infection experiment, at the endpoint, the right lung lobes were collected for H&E staining.

Histopathological examination using H&E staining method was performed as described previously76. Briefly, the histopathological changes of lung, such as inflammation, structure change and hemorrhage, were graded according to the following scoring system. Score 0 indicates clear structure of alveolar without inflammatory infiltration. Score 1 indicates mild inflammation, slightly widened alveolar septum and sparse mononuclear cells (monocytes and lymphocyte) infiltration. Score 2 indicates severe inflammation, thickening of alveolar wall and increased inflammatory infiltration of interstitial monocytes. Score 3–4 indicates alveolar septum widened significantly, increased infiltration of inflammatory cells. Score 5 indicates extensive exudation and widened septum, smaller alveolar cavity, septal bleeding, and infiltration of alveolar cells. Score >5 indicates a large number of cells infiltrated into the alveolar cavity; the alveolar cavity disappeared; the septum fused, and a transparent membrane was formed on the alveolar wall. Five fields of each section were randomly chosen for evaluation of histopathological changes according to the scoring system above. Histopathological changes of the lung from every hamster were graded based on thickening or consolidation of pulmonary septum, bleeding of pulmonary septum, infiltration of inflammatory cells, vascular thrombosis and distribution area of dust cells. The total score of each index is the final score of histopathological changes for each hamster.

qRT-PCR (Bio-Rad, CFX384) was used to measure viral gRNA and sgRNA (the latter of which is indicative of virus replication) in lung tissues. Data are normalized by tissue weight and are reported as copies of RNA determined by comparing the cycle threshold (CT) values from the unknown samples to CT values from a positive-sense SARS-CoV-2 RNA standard curve77. The primers and probe sequences used for gRNA were derived from the N gene (forward, 5′-GGGGAACTTCTCCTGCTAGAAT-3′; reverse, 5′-CAGACATTTTGCTCTCAAGCTG-3′; probe, 5′-FAM-TTGCTGCTGCTTGACAGATT-TAMRA-3′), according to the sequences recommended by the WHO and the China CDC. SARS-CoV-2 E gene subgenomic mRNA (sgRNA), indicative of virus replication, was assessed by qRT-PCR as previously described78, using the following primers and probe sequences (forward, 5′-CGATCTCTTGTAGATCTGTTCTC-3′; reverse, 5′-ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA-3′; probe, 5′-FAM-ACACTAGCCATCCTTACTGCGCTTCG-BHQ-3′). TCID50 was measured using Vero cell infection experiment.

Toxicology studies in SD rats and monkeys

All toxicology studies followed GLP and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of JOINN Laboratories, China. Male and female (6–8 w of age), specific-pathogen-free SD rat (Zhejiang Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.), as well as male and female (2.9–3.7 years of age) cynomolgus monkeys (Guangxi Weimei Bio-Tech CO., Ltd.) were used. For both the rat and the monkey studies, HH-120 aerosols were generated by nebulizing 10 mg/mL HH-120 solution and were given via an inhalation exposure system connected to four Aerogen Solo nebulizer systems. The target-delivered doses and the actual delivered doses were calculated using the same method as for the rat PK study. The first dosing day was defined as Day 1.

Two-week repeated dose toxicology study in SD rats: A total of 120 SD rats (60/sex) were randomly assigned to four groups (15/sex/group), and given fresh air, HH-120 formulation buffer, or HH-120 BID at target delivered dose levels of 5 or 15 mg/kg/dose (corresponding to actual delivered doses of 4.884 or 17.178 mg/kg/dose) for 14 consecutive days followed by a two-week recovery period. 10/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of dosing period (D16) and 5/sex/group rats were euthanatized at the end of recovery period (D29). Toxicological parameters evaluated included clinical observations, ophthalmology, respiratory functions, body weight, food consumption, laboratory tests (hematology, coagulation, clinical chemistry, urinalysis, cytokines, T lymphocyte subsets), organ weight, gross anatomy, and histopathology. Respiratory functions (tidal volume and respiratory frequency) were monitored with a EMKA whole body plethysmography (WBP) pulmonary system (EMKA TECHNOLOGIES Inc.) before dose initiation (D-1), within 2 h after the first dose on D2, D7, D13, and D28 (the recovery period). Data were analyzed by a IOX software (Version 2.9.4.31). Blood samples were collected on D16 and D29 from all euthanasia animals, CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets were analyzed by Flow Cytometry (BD LSRFortessa) (Supplementary Fig. 5a); TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 levels in serum were measured using Cytometric Bead Array (CBA) kits by Flow Cytometry (BD LSRFortessa).

Two-week repeated dose toxicology study in monkeys: A total of 30 cynomolgus monkeys (15/sex) were randomly assigned to three groups (5/sex/group) and given fresh air or HH-120 BID at target delivered dose levels of 2.5 or 8 mg/kg/dose (corresponding to actual delivered doses of 2.831 or 9.202 mg/kg/dose) for 14 consecutive days followed by a 2-week recovery period. At the end of dosing period (D15), 3/sex/group monkeys were euthanatized, and remaining monkeys (2/sex/group) were euthanatized at the end of recovery period (D29). Toxicological parameters evaluated included clinical observations, ophthalmology, ECG waveforms, blood pressure, body temperature, respiratory functions, oxygen saturation, body weight, food consumption, laboratory tests (hematology, coagulation, clinical chemistry, urinalysis, cytokines, C3 and C4, T lymphocyte subsets), organ weight, gross anatomy, and histopathology. Respiratory functions (tidal volume and respiratory frequency) were monitored with a EMKA non-invasive physiological signal telemetry system before dose initiation (D-5), 10 min before the first dose on D8 and immediately (<10 min), 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h post the first dose on D8, D13 and at the recovery period (D27). Data were analyzed by IOX software (Version 2.10.8.6). Blood samples were collected on five or six days before dose initiation, on D8, at the end of the dosing (D15), at the end of the recovery period (D29), CD3+, CD3+CD4+, CD3+CD8+ T lymphocyte subsets were analyzed by Flow Cytometry (BD FACSCalibur) (Supplementary Figure 5b); TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-6 levels in serum were measured using CBA kits by Flow Cytometry (BD FACSCalibur).

At the end of dosing period and recovery period, animals were humanly euthanized followed by complete necropsy. Tissues, including adrenal glands, aorta, bone with bone marrow from femur and sternum, brain, nasal cavity (turbinate, nasopharynx and nasal associated lymphoid tissue), epididymides, esophagus, eyes with optic nerves, heart, kidneys, lacrimal glands, large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum), larynx, liver, lung with bronchi, lymph nodes (bronchial, mandibular, mesenteric, inguinal), mammary gland, sciatic nerve, ovaries with oviducts, peyer’s Patch, pancreas, prostate, pituitary, salivary glands (parotid, mandibular, sublingual), seminal vesicles, skeletal muscle (biceps femoris), skin (close to mammary), small intestines (duodenum, jejunum, ileum), spinal cord (cervical, thoracic, lumbar), spleen, stomach, testes, thymus, thyroid glands with parathyroids, tongue, trachea, urinary bladder, uterus with cervix, and vagina tissues in both rats and monkeys; harderian glands in rats; gallbladder in monkeys were collected. Collected tissues were processed with routine histological methods: embedded in paraffin, sectioned, mounted on slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Slides from fresh air group and 15 mg/kg HH-120 group in the rat study and all tissue slides in monkey studies were examined microscopically by a certified pathologist and peer reviewed by a JSTP (Japanese Society of Toxicologic Pathology) board certified pathologist. Findings were described and categorized by the study pathologist using standardized nomenclature79,80. A five-step grading system of minimal, slight, moderate, marked, or severe was used to rank the severity of microscopic lesions for comparison among groups as appropriate (Supplementary Table 6).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9 and the statistic tests are described in the figure legends.

Data availability

All data are included in the article and supplementary materials. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Harvey, W. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 409–424 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608, 603–608 (2022).

Cao, Y. et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron infection. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04980-y (2022).

Liu, L. et al. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04388-0 (2021).

Takashita, E. et al. Efficacy of antiviral agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA.2. N. Engl. J. Med. 386, 1475–1477 (2022).

Wong, C. K. H. et al. Real-world effectiveness of early molnupiravir or nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 without supplemental oxygen requirement on admission during Hong Kong’s omicron BA.2 wave: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00507-2 (2022).

Waters, M. D., Warren, S., Hughes, C., Lewis, P. & Zhang, F. Human genetic risk of treatment with antiviral nucleoside analog drugs that induce lethal mutagenesis: The special case of molnupiravir. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 63, 37–63 (2022).

Gordon, C. J., Tchesnokov, E. P., Schinazi, R. F. & Gotte, M. Molnupiravir promotes SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis via the RNA template. J. Biol. Chem. 297, 100770 (2021).

Ledford, H. COVID antiviral pills: what scientists still want to know. Nature 599, 358–359 (2021).

Arbel, R. et al. Nirmatrelvir use and severe Covid-19 outcomes during the Omicron surge. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 790–798 (2022).

Menni, C. et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet 399, 1618–1624 (2022).

Sigal, A., Milo, R. & Jassat, W. Estimating disease severity of Omicron and Delta SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 267–269 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. New understanding of the damage of SARS-CoV-2 infection outside the respiratory system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 127, 110195 (2020).

Respaud, R., Vecellio, L., Diot, P. & Heuze-Vourc’h, N. Nebulization as a delivery method for mAbs in respiratory diseases. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 12, 1027–1039 (2015).

Zhou, P. et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579, 270–273 (2020).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280.e278 (2020).

Li, W. et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 426, 450–454 (2003).

Li, F., Li, W., Farzan, M. & Harrison, S. C. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 309, 1864–1868 (2005).

Temmam, S. et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells. Nature 604, 330–336 (2022).

Tipnis, S. R. et al. A human homolog of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Cloning and functional expression as a captopril-insensitive carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33238–33243 (2000).

Yan, R. et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367, 1444–1448 (2020).

Meng, B. et al. Altered TMPRSS2 usage by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron impacts infectivity and fusogenicity. Nature 603, 706–714 (2022).

Scudellari, M. How the coronavirus infects cells—and why Delta is so dangerous. Nature 595, 640–644 (2021).

Ferrari, M. et al. Characterization of a novel ACE2-based therapeutic with enhanced rather than reduced activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants. J. Virol. 95, e0068521 (2021).

Monteil, V. et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infections in engineered human tissues using clinical-grade soluble human ACE2. Cell 181, 905–913.e907 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. hACE2 Fc-neutralization antibody cocktail provides synergistic protection against SARS-CoV-2 and its spike RBD variants. Cell Discov. 7, 54 (2021).

**ao, T. et al. A trimeric human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as an anti-SARS-CoV-2 agent. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 28, 202–209 (2021).

Glasgow, A. et al. Engineered ACE2 receptor traps potently neutralize SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 28046–28055 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Potent prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy of recombinant human ACE2-Fc against SARS-CoV-2 infection in vivo. Cell Discov. 7, 65 (2021).

Lei, C. et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus by recombinant ACE2-Ig. Nat. Commun. 11, 2070 (2020).

Chan, K. K. et al. Engineering human ACE2 to optimize binding to the spike protein of SARS coronavirus 2. Science 369, 1261–1265 (2020).

Hassler, L. et al. A novel soluble ACE2 protein provides lung and kidney protection in mice susceptible to lethal SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 33, 1293–1307 (2022).

Smith, R. I., Coloma, M. J. & Morrison, S. L. Addition of a mu-tailpiece to IgG results in polymeric antibodies with enhanced effector functions including complement-mediated cytolysis by IgG4. J. Immunol. 154, 2226–2236 (1995).

Mekhaiel, D. N. et al. Polymeric human Fc-fusion proteins with modified effector functions. Sci. Rep. 1, 124 (2011).

Bussani, R. et al. Persistence of viral RNA, pneumocyte syncytia and thrombosis are hallmarks of advanced COVID-19 pathology. EBioMedicine 61, 103104 (2020).

Mlcochova, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature 599, 114–119 (2021).

Ullah, I. et al. Live imaging of SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice reveals that neutralizing antibodies require Fc function for optimal efficacy. Immunity 54, 2143–2158.e2115 (2021).

Ogando, N. S. et al. SARS-coronavirus-2 replication in Vero E6 cells: replication kinetics, rapid adaptation and cytopathology. J. Gen. Virol. 101, 925–940 (2020).

Piepenbrink, M. S. et al. Therapeutic activity of an inhaled potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing human monoclonal antibody in hamsters. Cell Rep. Med. 2, 100218 (2021).

Ku, Z. et al. Nasal delivery of an IgM offers broad protection from SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nature 595, 718–723 (2021).

McSweeney, M. D. et al. Stable nebulization and muco-trap** properties of regdanvimab/IN-006 support its development as a potent, dose-saving inhaled therapy for COVID-19. Bioeng. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/btm2.10391 (2022).

Gerde, P., Nowenwik, M., Sjoberg, C. O. & Selg, E. Adapting the aerogen mesh nebulizer for dried aerosol exposures using the preciseinhale platform. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 33, 116–126 (2020).

Fernandez Tena, A. & Casan Clara, P. Deposition of inhaled particles in the lungs. Arch. Bronconeumol. 48, 240–246 (2012).

Kuehl, P. J. et al. Regional particle size dependent deposition of inhaled aerosols in rats and mice. Inhal. Toxicol. 24, 27–35 (2012).

Lenfant, C. Discovery of endogenous lung surfactant and overview of its metabolism and actions. in Lung Surfactants: Basic Science and Clinical Applications, (ed Notter R.) 119–149 (Marcel Dekker. Inc., New York, NY), (2000).

Phillips, J. E. Inhaled efficacious dose translation from rodent to human: a retrospective analysis of clinical standards for respiratory diseases. Pharm. Ther. 178, 141–147 (2017).

Frohlich, E., Mercuri, A., Wu, S. & Salar-Behzadi, S. Measurements of deposition, lung surface area and lung fluid for simulation of inhaled compounds. Front. Pharm. 7, 181 (2016).

Fronius, M., Clauss, W. G. & Althaus, M. Why do we have to move fluid to be able to breathe? Front. Physiol. 3, 146 (2012).

Luan, J., Lu, Y., **, X. & Zhang, L. Spike protein recognition of mammalian ACE2 predicts the host range and an optimized ACE2 for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 526, 165–169 (2020).

Sia, S. F. et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature 583, 834–838 (2020).

Tostanoski, L. H. et al. Ad26 vaccine protects against SARS-CoV-2 severe clinical disease in hamsters. Nat. Med. 26, 1694–1700 (2020).

Osterrieder, N. et al. Age-dependent progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection in syrian hamsters. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v12070779 (2020).

Lieber, C. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 VOC type and biological sex affect molnupiravir efficacy in severe COVID-19 dwarf hamster model. Nat. Commun. 13, 4416 (2022).

MacLoughlin, R. J. et al. Optimization and dose estimation of aerosol delivery to non-human primates. J. Aerosol Med. Pulm. Drug Deliv. 29, 281–287 (2016).

Nikula, K. J. et al. STP position paper: interpreting the significance of increased alveolar macrophages in rodents following inhalation of pharmaceutical materials. Toxicol. Pathol. 42, 472–486 (2014).

Iketani, S. et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 604, 553–556 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Receptor and viral determinants of SARS-coronavirus adaptation to human ACE2. EMBO J. 24, 1634–1643 (2005).

Mannar, D. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein-ACE2 complex. Science 375, 760–764 (2022).

Hoffmann, M., Zhang, L. & Pohlmann, S. Omicron: Master of immune evasion maintains robust ACE2 binding. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7, 118 (2022).

Hansen, J. et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science 369, 1010–1014 (2020).

Jones, B. E. et al. The neutralizing antibody, LY-CoV555, protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates. Sci. Transl. Med. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abf1906 (2021).

Donoghue, M. et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ. Res. 87, E1–E9 (2000).

Khan, A. et al. A pilot clinical trial of recombinant human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care 21, 234 (2017).

Zhang, L. et al. An ACE2 decoy can be administered by inhalation and potently targets omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. EMBO Mol. Med. 14, e16109 (2022).

Yeung, M. L. et al. Soluble ACE2-mediated cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 via interaction with proteins related to the renin-angiotensin system. Cell 184, 2212–2228.e2212 (2021).

DeFrancesco, L. COVID-19 antibodies on trial. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1242–1252 (2020).

Yuan, M. et al. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science 368, 630–633 (2020).

Li, D. et al. A potent human neutralizing antibody Fc-dependently reduces established HBV infections. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.26738 (2017).

Crawford, K. H. D. et al. Protocol and reagents for pseudoty** lentiviral particles with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for neutralization Assays. Viruses https://doi.org/10.3390/v12050513 (2020).

Nie, J. et al. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody by a pseudotyped virus-based assay. Nat. Protoc. 15, 3699–3715 (2020).

Yang, R. et al. Development and effectiveness of pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 system as determined by neutralizing efficiency and entry inhibition test in vitro. Biosaf. Health 2, 226–231 (2020).

Wang, G. et al. Dalbavancin binds ACE2 to block its interaction with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in animal models. Cell Res. 31, 17–24 (2021).

Lu, L. et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant by sera from BNT162b2 or Coronavac vaccine recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab1041 (2021).

Alexander, D. J. et al. Association of Inhalation Toxicologists (AIT) working party recommendation for standard delivered dose calculation and expression in non-clinical aerosol inhalation toxicology studies with pharmaceuticals. Inhal. Toxicol. 20, 1179–1189 (2008).

Gabrielson, J. P. et al. Precision of protein aggregation measurements by sedimentation velocity analytical ultracentrifugation in biopharmaceutical applications. Anal. Biochem. 396, 231–241 (2010).

Xu, K. et al. Protective prototype-Beta and Delta-Omicron chimeric RBD-dimer vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 185, 2265–2278.e2214 (2022).

Lu, S. et al. Comparison of nonhuman primates identified the suitable model for COVID-19. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5, 157 (2020).

Wolfel, R. et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 581, 465–469 (2020).

Schafer, K. A. et al. Use of severity grades to characterize histopathologic changes. Toxicol. Pathol. 46, 256–265 (2018).

Shackelford, C., Long, G., Wolf, J., Okerberg, C. & Herbert, R. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of nonneoplastic lesions in toxicology studies. Toxicol. Pathol. 30, 93–96 (2002).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China grant 2020YFA0707401 and Bei**g Municipal Science and Technology Commission fund Z201100005420016 to W.L.; and the following funds to K.Y.Y.: the Health and Medical Research Fund 20190742, COVID1903010—Project 12, and 21200622; the Food and Health Bureau, the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (China), the Collaborative Research Fund (C7142-20G) and the Theme-Based Research Scheme (T11-709/21-N); the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (China), and the National Key Research and Development Program (2021YFC0866100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.C., J.S., and W.L. Methodology: J.Liu, F.M., Y.Q., R.Sa, Y.L., R.S., R.J., H.C., and M.F. Investigation: aerosol inhalation test and aerodynamic characterization were performed or supervised by J.L. and F.M; HH-120 molecular design, cloning and expression: J.C. C.L., J.L., Y.Q.; ADCC, ADCP, and fusion assays were performed by Y.Y. and Y.Q.; pseudotyped virus neutralizing assays were performed by Y.Q., L.F., and Y.Sun; HH-120 binding assays were performed by X.Liu, F.Y., X.T. C.L., and R.Sa; negative-stain EM was performed by G.Y.; authentic virus neutralization experiments were performed by M.L.Y., K.Y.Y., B.H., W.T., S.L. and X.P.; efficacy studies in hamsters were performed by S.L. and X.P.; toxicity studies were supervised by F.M., G.L., and P.C.; PK profiling experiments were performed by J.L., R.Sa, R.P., X.Li, and F.M.; CHO stable cell line, cell culture and protein purification processes were developed by P.H., D.H., Z.L., Y.D., H.L., Y.C., Y.Sheng, and Y.Z.; Resources: Y.L., R.S., R.J., H.C., and M.F.; Supervision: J.S. and W.L. Writing and editing: J.Liu, F.M., Y.Q., J.S., and W.L.; Review: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J.Liu, F.M., J.C., Y.Q., C.L., G.Y., G.L., Y.Y., P.H., D.H., Z.L., Y.D., Y.S., H.L., F.Y., P.C., R.S., R.P., X.L., J.Luo, Y.C., Y.Z., Y.L., J.S., and W.L. are employee and/or stakeholders of Huahui Health Ltd. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Joseph F Standing and the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Mao, F., Chen, J. et al. An IgM-like inhalable ACE2 fusion protein broadly neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Commun 14, 5191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40933-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40933-3

- Springer Nature Limited