Abstract

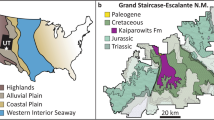

The abundance of dinosaur eggs in Upper Cretaceous strata of Henan Province, China led to the collection and export of countless such fossils. One of these specimens, recently repatriated to China, is a partial clutch of large dinosaur eggs (Macroelongatoolithus) with a closely associated small theropod skeleton. Here we identify the specimen as an embryo and eggs of a new, large caenagnathid oviraptorosaur, Beibeilong sinensis. This specimen is the first known association between skeletal remains and eggs of caenagnathids. Caenagnathids and oviraptorids share similarities in their eggs and clutches, although the eggs of Beibeilong are significantly larger than those of oviraptorids and indicate an adult body size comparable to a gigantic caenagnathid. An abundance of Macroelongatoolithus eggs reported from Asia and North America contrasts with the dearth of giant caenagnathid skeletal remains. Regardless, the large caenagnathid-Macroelongatoolithus association revealed here suggests these dinosaurs were relatively common during the early Late Cretaceous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

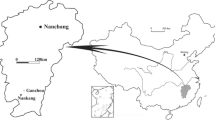

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, thousands of dinosaur eggs were excavated and collected by local farmers from Cretaceous rocks of Henan, China1. During this time, China struggled to control the export of these eggs, many of which were sold overseas in rock and gem shows, stores, and markets by the early 1990s. Some of these exported eggs were prepared in other countries and revealed beautifully preserved embryos2.

Of the numerous specimens exported from China, one of the most significant turned out to be a small skeleton associated with a partial clutch of the largest known type of dinosaur egg (that is, Macroelongatoolithus). The unprepared specimen was imported into the USA in mid-1993 by The Stone Company, which exposed the skeleton and eggs during preparation (Supplementary Fig. 1). The specimen was featured in a cover article for National Geographic Magazine2, and the skeleton became popularly known as ‘Baby Louie’ in recognition of Louis Psihoyos, the photographer for the article.

In 2001, Baby Louie was acquired from the Stone Company by the Indianapolis Children’s Museum where it was put on public exhibit for 12 years. The museum’s intention was to repatriate the specimen to China, but an agreement for its return was not finalized until 2013. In December 2013, twenty years after the specimen was collected, Baby Louie found its final home in its province of origin at the Henan Geological Museum3.

Although Baby Louie was known to have been collected in Henan Province, the exact locality was uncertain when the specimen was imported into the United States. However, it has since been learned that it was collected by Mr Zhang Fengchen in the ** bones, with bones primarily from the right side visible (Fig. 3a,b). The skull is 66 mm long as preserved, and the orbit is large and round. Most of the right premaxilla is missing although two fragments adhere to the anterior margin of the nasal, one of which reveals it has a sculptured external surface. The right maxilla, located anterior to the lacrimal and jugal, lacks teeth and alveoli. It is relatively short and low, and forms the anteroventral margin of a small antorbital fenestra. The maxilla has a pronounced anteroposterior shelf below the antorbital fossa, which is continuous anteriorly with a dorsoposteriorly trending ridge on the external surface of the maxilla (Fig. 3a,b). The two ridges demarcate the antorbital fossa. The maxilla extends a short distance ventromedially from the ridge below the antorbital fossa, but this palatal shelf is broken off anteromedially. The nasals, visible in ventral view, are fused posteriorly between the narial openings; the suture is visible anteriorly, which is similar to the immature individual of the oviraptorid Yulong14. Four aligned nutrient foramina penetrate the outside margin of the right nasal. The right lacrimal is an open crescentic bone that forms the anterior margin of the orbit. A depression on the dorsal edge of the posterior process of the lacrimal is the contact for the frontal, indicating that the frontal overlaps this bone. The antorbital (vertical) process of the lacrimal is concave posteriorly. A lacrimal foramen extends into the bone from this concavity near mid-height. The anterolateral margin of the orbit is a sharply defined ridge as in other oviraptorosaurs. The right jugal has a suborbital process that is long and low, similar to those of most oviraptorosaurs, and tapers anteriorly to contact the maxilla and lacrimal (Fig. 3b). The triangular postorbital process is a short, posterodorsally oriented projection. The frontal is highly domed and both the interfrontal and frontoparietal sutures are visible. The postorbital process of the frontal has a deep, triangular groove on its dorsal surface that broadens ventrolaterally. The incomplete right postorbital is a slender, arcuate bone that extends between the frontal and posterodorsal process of the jugal. The dorsal process of the quadratojugal is tall and slender as in oviraptorosaurs. It expands ventrally, but the jugal process was broken and presumably lost. The right quadrate has a shallow notch that separates the lateral and medial condyles, and the posterior surface is shallowly concave in lateral view. The triradiate right ectopterygoid (Fig. 3a,b), visible in the right orbit, has a well-developed pneumatic ectopterygoid fossa on the dorsal side. Other bones, probably from the palate and braincase, are present in the orbit but are difficult to identify.

Bones present from the lower jaw include the dentary, surangular, angular, and articular (Fig. 3a,b). The dentary has a general morphology similar to those of other oviraptorosaurs, particularly those specimens in which the dentaries are unfused7,33,34,35. The two dentaries are not tightly sutured or fused at the symphysis in HGM 41HIII1219, and most of the left dentary is exposed in the region of the chest in lingual view (Fig. 2). The left dentary is relatively short (27 mm along the ventral margin, or 32 mm as restored in Fig. 3c) and deep (18 mm at the anterior margin of the external mandibular fenestra), with proportions that are most similar to Gigantoraptor and Microvenator (Supplementary Note 2). The dentary is thin and plate like, and as expected for oviraptorosaurs it has a sharp edentulous anterodorsal margin. Anteriorly, it curves medially to form a robust, steeply slo** symphysis (Fig. 3c). The symphysial region is downturned in relation to the ventral margin of the dentary. The symphysis has a rugose, anterodorsally inclined contact. The posterior edge of the left dentary is deeply emarginated due to a large external mandibular fenestra. A ridge on the lingual surface extends from midheight of the symphysis to the posterodorsal process, forming a shelf below the cutting edge of the jaw margin anterodorsally (Fig. 3c). A much weaker ridge extends along the ventral margin of the dentary to the posteroventral process, and above this is a shallow Meckelian groove as in other oviraptorosaurs34,36,37. The anterior terminus of the groove is above the ventral ridge as in Microvenator and oviraptorids34 rather than below the symphysis as in most caenagnathids36. Although most of both the posterodorsal and posteroventral processes are missing on the left dentary, the posteroventral process (as seen on the right dentary) probably extended farther posteriorly than the posterodorsal process. The right surangular is complete, although the anterior tip is covered by the right maxilla (Fig. 3b). The lateral surface of the surangular has a posteriorly tapering depression for articulation with the posterodorsal process of the dentary. Like Gigantoraptor8, it appears to lack a surangular spine. The dorsal margin curves posteroventrally from a relatively low coronoid prominence. The articular is not fused with the surangular. It has a pronounced convex crest-like articulation for the quadrate, typical of oviraptorids. The crest is noticeably longer anteroposteriorly than the quadrate condyles. The articular extends posteriorly into a short but pronounced retroarticular process that has a distinct concave posterior facet.

Most regions of the vertebral column are represented by about a dozen vertebrae that are generally incomplete and disarticulated (Fig. 2). An anterior cervical neural arch is visible in dorsal view, has a low neural spine, and an X-shaped dorsal profile like other oviraptorosaurs34. An isolated centrum in the region has parapophysis relatively high on the centrum, which suggests that it represents an anterior cervicodorsal vertebra. The last dorsal centrum is associated with its neural arch in front of the first sacral, and appears to have a large pleurocoel in its side. Although mostly covered by the right ilium, six sacrals are likely present based on the number of neural spines protruding above the dorsal edge of the ilium and on the spacing where spines are not visible.

Few elements of the pectoral girdle and forelimbs are identifiable (Fig. 2). The right scapula is strap-like and covered anteriorly by vertebrae of the presacral region, and a short fragment of the left scapula lies adjacent to it. In the same region, one curved piece may represent a furculum attached to an acromion fragment of the scapula. Two limb shafts largely covered by other bones may belong to the humeri. A complete ulna (L=29 mm) and partial radius are associated with another egg (#4) in the specimen, which may belong to the skeleton or to another perinate (Supplementary Note 1). The olecranon process of this ulna is poorly developed as in other embryonic oviraptorids38.

All bones of the pelvic girdle are represented (Fig. 3d). The right ilium is complete and 66 mm long. The preacetabular ala is about 1.5 times longer than the postacetabular blade. This proportion is similar to those of Chirostenotes, Microvenator, Nankangia, Nomingia and Rinchenia, whereas most oviraptorid dinosaurs have ilia with preacetabular and postacetabular lengths that are subequal. In lateral view, the ilium has a straight to gently convex dorsal margin, and the postacetabular process is squared off (Fig. 3d). The preacetabular process curves anteroventrally from the pubic peduncle, and is deep relative to the postacetabular process. The acetabulum forms a broad gentle arch, but there is no evidence of a supra-acetabular shelf. The right pubis is in contact with the pubic peduncle of the ilium (Fig. 3d), and inclines ventroposteriorly. The proximal part of the shaft extends along the anterior margin of the right femur. Most of the shaft is covered by the femur, and emerges distally for a short distance behind the distal half of the femur where it is broken. The left pubis lies directly under the right one, and extends most of length of the femur before it becomes covered. The left pubis exposes the pubic apron on the medial surface of the distal quarter. The pubes were not coossified at the pubic apron, representing another juvenile trait. The right ischium is displaced from the peduncle, and the rod-like shaft projects posteroventrally from the acetabulum. The proximal end of the ischium is underneath the ilium whereas the distal end is missing. A small portion of the obturator process is visible, but the ischium has rotated so it seems to be dorsal to the shaft (Fig. 3d).

The hindlimbs are represented by several elements (Fig. 2), although most bones of the foot are missing. The left femur projects anteriorly from beneath the ilium (Fig. 3d), and ribs cover the distal end. The right femur is exposed in lateral view and is articulated with the acetabulum and tibia/fibula. The ends of the right femur are incomplete. The proximal end extends into the acetabulum but appears to have been largely destroyed by an insect boring, whereas the distal end would have been capped by a cartilaginous extension of the bone. As preserved, the right femur is 66.8 mm long. However, the distance between the top of the acetabulum and the head of the tibia is 75 mm, which is probably a closer approximation of the actual length of the femur. The femur is robust and slightly bowed (Fig. 2). Like Gigantoraptor but unlike other oviraptorosaurs39, there is no evidence of a ridge extending along the shaft between the anterior trochanter and the distal medial condyle. The distal end has a shallow posterior depression that separates the lateral and medial ‘condyles’, both of which are abruptly truncated in a flat surface that is not subdivided distally (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The right tibia is missing its distal portion. The cnemial crest does not project far from the shaft as in other embryonic oviraptorosaurs33,38 (Supplementary Fig. 3b), and lacks the distinct boss that is present on the distal end of the crest in Citipati, Gigantoraptor and Nomingia39. The lateral (fibular) condyle is low and poorly defined, but continues distally in a distinct ridge that is connected with the fibular crest (Supplementary Fig. 3b). The fibular crest is low as in Gigantoraptor8, but has parallel, proximolaterally extending ridges for the attachment of ligaments. The shaft of the tibia is robust. The fibula had slid a short distance up the tibia, and is missing its distal half. Approximately 22 mm from the proximal end is a shallow depression that bounds a more distal moundlike, anterolaterally projecting iliofibularis tubercle (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Six disarticulated pedal phalanges in the region of the right knee probably represent II-1, III-2, both right and left IV-2, IV-3 and IV-4.

Maturity and growth

The size, posture, and other features of the skeleton indicate the animal was immature (likely embryonic) at the time of death even though it is not preserved within the confines of an egg. The large orbit, domed frontals, lack of fused skull bones, ill-defined or undeveloped processes of long bones, unfused neural arches and highly vascularized bone texture of the skeleton are typical of embryonic or immature individuals33,38,40. The chin of Beibeilong is tucked down towards the chest in a posture reminiscent of in ovo dinosaur33, crocodile41,42 and bird43 embryos (Fig. 2). The curled skeleton is only 23 cm long (as measured from the top of the skull to the base of the tail) and would readily fit inside an egg over 40 cm long, probably occupying no more than two-thirds of the egg volume (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 4). Given that the skeleton is not preserved within an egg and that its orientation is inconsistent with that of the eggs, it is likely that the embryo was forcefully extruded or removed from one of the underlying eggs to its current position.

Generalizations relevant to growth in large caenagnathids can be made by comparing the Beibeilong embryo to the adult specimen of Gigantoraptor. In Beibeilong, the dentaries are not fused at the mandibular symphysis (like in the small, juvenile caenagnathid Microvenator) whereas they are completely fused in Gigantoraptor and in other adult caenagnathids, indicating that fusion of the dentaries probably occurred post-hatching. Similarities in various proportions of the dentary between Beibeilong and Gigantoraptor suggest that the overall shape of the mandible remained relatively consistent in large caenagnathids during growth (Supplementary Note 2).The mandible-to-femur length ratio is high (∼0.87) in Beibeilong but low in Gigantoraptor (0.45)8, reflecting a considerable difference in relative skull size between the two taxa. However, a large difference in such ratios between individuals of drastically different ontogenetic stages within a species is also not unexpected through ontogeny44.

Phylogenetic analysis

A phylogenetic analysis was conducted in order to determine the position of Beibeilong sinensis gen. et sp. nov. within Oviraptorosauria using the character matrix of Funston and Currie45. On the basis of 37 taxa (incl. Herrerasaurus, Velociraptor and Archaeopteryx as outgroups) and 250 characters (Supplementary Table 4), 608 most parsimonious trees were recovered where a strict consensus tree (Fig. 6) supports the monophyly of several clades within Oviraptorosauria, including Caudipterygidae, Caenagnathoidea, Oviraptoridae and Caenagnathidae as in recent analyses45,46. Beibeilong sinensis is nested within Caenagnathidae, and is more derived than Microvenator celer but is basal to Gigantoraptor erlianensis. Its phylogenetic position is consistent regardless of whether or not the characters we consider as ontogenetically variable (that is, characters 82, 84, 162, 165, 166, 184, 185, 187, 222, 224 and 248) are coded for Beibeilong sinensis. Exclusion of such characters (that is, coded with a ‘?’) reveals three autapomorphies for the new species: subantorbital portion of the maxilla is inset medially (character 10, state 1), posterior end of the postacetabular process is truncated or broadly rounded (character 141, state 0), and accessory trochanter of the femur is weakly developed (character 204, state 0). Coding these characters recovers two additional autapomorphies for Beibeilong that are likely due to immaturity of the individual, including: anterodorsal margin of dentary straight in lateral view (character 84, state 0), and frontals strongly arched, projecting well above orbit in lateral view to contribute to nasal-frontal crest (character 162, state 1). The stability of the phylogenetic position of Beibeilong regardless of whether or not ontogenetically-variable characters are coded suggests that Beibeilong is more basal than Gigantoraptor and not an embryonic individual of this taxon.

Discussion

The Baby Louie specimen has been key to determination of the taxonomic affinity of the largest known dinosaur egg and nest type (Macroelongatoolithus) since shortly after its illegal export from China over two decades ago (Supplementary Note 3). Its description and taxonomic identification herein reveals the first known occurrence of eggs and embryonic remains of a caenagnathid oviraptorosaur. As the egg layers of Macroelongatoolithus, caenagnathids produced the largest known eggs (reported to have reached 61 cm in lengthNomenclatural act This published work and the nomenclatural act it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the proposed online registration system for the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). The ZooBank LSID (Life Science Identifier) can be resolved and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix ‘ http://zoobank.org/’. The LSID for this publication is: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:00CBBC39-41BC-4900-83AE-C38B5A25F970. The authors confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and its Supplementary Information files.Data availability

Additional information

How to cite this article: Pu, H. et al. Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China. Nat. Commun. 8, 14952 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14952 (2017).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Zhou, S. Q., Cui, B. J., Guo, Y. F., Qian, X. H. & **, H. X. Approaching the World of Dinosaur Eggs China University of Geosciences Press (2010).

Currie, P. J. The great dinosaur egg hunt. Nat. Geogr. Mag. 189, 96–111 (1996).

Pu, H. Y. Legend of Baby Dinosaur: the Return Home of Baby Louie. ISBN 978-7-5357-8169-7, 132 (Pecking Natural Science Organization Production, Zhengzhou, China, 2014).

Norell, M. A. et al. A theropod dinosaur embryo and the affinities of the Flaming Cliffs Dinosaur eggs. Science 266, 779–782 (1994).

Osmólska, H., Currie, P. J. & Barsbold, R. in The Dinosauria 2nd ed. eds Weishampel D. B., Dodson P., Osmólska. H. 165–183University of California Press (2004).

Xu, X., Cheng, Y. N., Wang, X. L. & Chang, C. H. An unusual oviraptorosaurian dinosaur from China. Nature 419, 291–293 (2002).

Ji, Q., Currie, P. J., Norrell, M. A. & Ji, S. A. Two feathered dinosaurs from northeastern China. Nature 393, 753–761 (1998).

Xu, X., Tan, Q. W., Wang, J. M., Zhao, X. J. & Tan, L. A gigantic bird-like dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of China. Nature 447, 844–847 (2007).

Dong, Z. M. & Currie, P. J. On the discovery of an oviraptorid skeleton on a nest of eggs at Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia, People’s Republic of China. Can. J. Earth Sci. 33, 631–636 (1996).

Xu, X. et al. A new oviraptorid from the upper Cretaceous of Nei Mongol, China, and its stratigraphic implications. Vertebr. PalAsia 51, 85–101 (2013).

He, T., Zhou, Z. H. & Wang, X. L. A new genus and species of caudipterid dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China. Vert. PalAsia 46, 178–189 (2008).

Longrich, N. R., Currie, P. J. & Dong, Z. M. A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia. Palaeontology 53, 945–960 (2010).

Lü, J. C. et al. A preliminary report on the new dinosaurian fauna from the Cretaceous of the Ruyang Basin, Henan Province of central China. J. Paleontol. Society Korea 25, 43–56 (2009).

Lü, J. C. et al. Chicken-sized oviraptorid dinosaurs from central China and their ontogenetic implications. Naturwissenschaften 100, 165–175 (2013).

Lü, J. C. A new oviraptorosaurid (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of southern China. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 22, 871–875 (2002).

Lü, J. C. Oviraptorid Dinosaurs from Southern China 208Geological Publishing House (2005).

Lü, J. C. & Zhang, B. K. A new oviraptorid (Theropod: Oviraptorosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Nanxiong Basin, Guangdong Provinces of southern China. Acta Palaeontol. Sinica 44, 412–422 (2005).

Sato, T., Cheng, Y. N., Wu, X. C., Zelenitsky, D. K. & Hsiao, Y. F. A pair of shelled eggs inside a female dinosaur. Science 308, 375 (2005).

Xu, X. & Han, F. L. A new oviraptorid dinosaur (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of China. Vertebr. PalAsia 48, 11–18 (2010).

Wang, S., Sun, C., Sullivan, C. & Xu, X. A new oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of southern China. Zootaxa 3640, 242–257 (2013).

Wei, X. F., Pu, H. Y., Xu, L., Liu, D. & Lü, J. C. A new oviraptorid dinosaur (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Jiangxi Province, southern China. Acta Geologica Sinica 87, 899–904 (2013).

Lü, J. C., Yi, L. P., Zhong, H. & Wei, X. F. A new oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of Southern China and its paleoecological implications. PLoS ONE 8, e80557 (2013).

Lü, J. C. et al. A new oviraptorid dinosaur (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of southern China and its paleobiogeographical implications. Sci. Rep. 5, 11490 (2015).

Lü, J. C., Chen, R. J., Brusatte, S. L., Zhu, Y. X. & Shen, C. Z. (2016) A Late Cretaceous diversification of Asian oviraptorid dinosaurs: evidence from a new species preserved in an unusual posture. Sci. Rep. 6, 35780 (2016).

Marsh, O. C. Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part V. Am. J. Sci. 21, 417–423 (1881).

Barsbold, R. On a new Late Cretaceous family of small theropods (Oviraptoridae fam. n.) of Mongolia. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 226, 685–688 (in Russian) (1976).

Sternberg, R. M. A toothless bird from the Cretaceous of Alberta. J. Paleontol. 14, 81–85 (1940).

Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Henan Province. Regional Geology of Henan Province 1–772Geological Publishing House (1989).

Liang, X., Wen, S., Yan, D., Zhou, S. & Shichong, W. Dinosaur eggs and dinosaur egg-bearing deposits (Upper Cretaceous) of Henan Province, China: occurrences, palaeoenvironments, taphonomy and preservation. Prog. Nat. Sci. 19, 1587–1601 (2009).

Clark, J. M., Norell, M. A. & Chiappe, L. M. An oviraptorid skeleton from the Late Cretaceous of Ukhaa Tolgod, Mongolia, preserved in an avian-like brooding position over an oviraptorid nest. Am. Mus. Novit. 3265, 1–36 (1999).

Li, Y., Yin, Z. & Liu, Y. The discovery of a new genus of dinosaur egg from **xia, Henan, China. J. Wuhan Inst. Chem. Technol. 17, 38–41 (1995).

Wang, D. & Zhou, S. The discovery of new typical dinosaur egg fossils from **xia Basin. Henan Geol. 13, 262–267 (in Chinese with English abstract) (1995).

Norell, M. A., Clark, J. M. & Chiappe, L. M. An embryonic oviraptorid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit. 3315, 1–17 (2001).

Makovicky, P. J. & Sues, H. D. Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of the theropod dinosaur Microvenator celer from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. Am. Mus. Novit. 3240, 1–27 (1998).

Wang, S., Zhang, S., Sullivan, C. & Xu, X. Elongatoolithid eggs containing oviraptorid (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria) embryos from the Upper Cretaceous of southern China. BMC Evol. Biol. 16, 67 (2016).

Currie, P. J., Godfrey, S. J. & Nessov, L. New caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) specimens from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. Can. J. Earth Sci. 30, 2255–2272 (1993).

Funston, G. F. & Currie, P. J. A previously undescribed caenagnathid mandible from the late Campanian of Alberta, and insights into the diet of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria). Can. J. Earth Sci. 51, 156–165 (2014).

Weishampel, D. B. et al. New oviraptorid embryos from Bugin-Tsav, Nemegt Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Mongolia, with insights into their habitat and growth. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 1110–1119 (2008).

Balanoff, A. M. & Norell, M. A. Osteology of Khaan mckennai (Oviraptorosauria: Theropoda). Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 372, 1–77 (2012).

Horner, J. R. & Currie, P. J. in Dinosaur Eggs and Babies eds Carpenter K., Hirsch K. F., Horner J. R. 312–336Cambridge University Press (1994).

Ferguson, M. W. in Biology of the Reptilia eds Gans C., Billet F. S., Manderson P. F. A. 14, 329–491Wiley and Sons (1985).

Kundrát, M., Cruikshank, A. R. I., Manning, T. W. & Nudds, J. Embryos of therizinosauroid theropods from the Upper Cretaceous of China: diagnosis and analysis of ossification patterns. Acta Zool. 89, 231–251 (2008).

Bellairs, R. & Osmond, M. Atlas of Chick Development 3rd edn Academic Press (2014).

Reisz, R. R. et al. Embryos of an early Jurassic prosauropod dinosaur and their evolutionary significance. Science 309, 761–764 (2005).

Funston, G. F. & Currie, P. J. A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 36, e1160910 (2016).

Lamanna, M. C., Sues, H. D., Schachner, E. R. & Lyson, T. R. A new large-bodied oviraptorosaurian theropod dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America. PLoS ONE 9, e92022 (2014).

Huh, M. et al. First record of a complete giant theropod egg clutch from Upper Cretaceous deposits, South Korea. Hist. Biol. 26, 218–228 (2014).

Zanno, L. & Makovicky, P. J. No evidence for directional evolution of body mass in herbivorous theropod dinosaurs. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 280, 84–89 (2013).

Campione, N. E., Evans, D. C., Brown, & Carrano, M. T. Body mass estimation in non-avian bipeds using a theoretical conversion to quadruped stylopodial proportions. Methods. Ecol. Evol. 5, 913–923 (2014).

Henderson, D. & Zelenitsky, D. K. Egg and body mass scaling in non-avian theropods. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 33, 74A (2006).

Wang, Q. Z., Zhao, Z. K., Wang, X. L., Jiang, Y. G. & Zhang, S. K. A new oogenus of macroelongatoolithid eggs from the Upper Cretaceous Chichengshan Formation of the Tiantai Basin, Zhejiang Province and a revision of the macroelogatoolithids. Acta Palaeontol. Sinica 49, 73–86 (2010).

Tsuihiji, T., Watabe, M., Barsbold, R. & Tsogtbaatar, K. A gigantic caenagnathid oviraptorosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of the Gobi Desert, Mongolia. Cretaceous Res. 56, 60–65 (2015).

**, X., Azuma, Y., Jackson, F. D. & Varricchio, D. J. Giant dinosaur eggs from the Tiantai Basin, Zhejiang Province, China. Can. J. Earth Sci. 44, 81–88 (2007).

Fang, X., Wang, Y. & Jiang, Y. On the Late Cretaceous fossil eggs of Tiantai, Zhejiang. Geol. Rev. 46, 105–111 (2000).

Watabe, M. & Suzuki, S. First discovery of dinosaur eggs and nests from Bayn Shire (Upper Cretaceous) in eastern Gobi, Mongolia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 17, 84A (1997).

Zelenitsky, D. K., Carpenter, K. & Currie, P. J. First record of elongatoolithid theropod eggshell from North America: the Asian oogenus Macroelongatoolithus from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 20, 130–138 (2000).

Simon, D. J. Giant dinosaur (theropod) eggs of the oogenus Macroelongatoolithus (Elongatoolithidae) from southeastern Idaho: taxonomic, paleobiogeographic, and reproductive implications. Unpublished MSc thesis, 110 (Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, USA, (2014).

Hirsch, K. F. & Quinn, B. Eggs and eggshell fragments from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 10, 491–511 (1990).

Goloboff, P., Farris, J. & Nixon, K. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774–786 Program and documentation available from www.zmuc.dk/public/phylogeny (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank Charlie Magovern for all the work he invested in the preparation of the specimen, and Charlie and Flo Magovern for their hospitality. Jeff Paget and Dallas Evans (Indianapolis Children’s Museum) assisted with the study of the specimen when it was in Indianapolis, but more importantly facilitated its return to China. Mr Zhang **ngliao, the former director of Henan Geological Museum, and Professor Dong Zhiming of the IVPP who helped in the return of the specimen to China are also gratefully acknowledged. And finally, our thanks go to Louis Psihoyos, who is the namesake of Baby Louie, for his involvement in the project and his creative talents. J.L. was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 41672019; 41272022), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (Grant No.: JB1504) and China Geological Survey (Grant No:DD20160201). D.K.Z. and P.J.C. were funded by NSERC Discovery Grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., P.J.C and D.K.Z designed the project. J.L., H.P., L.X., S.J., L. X, H.C., T.L., and C.S. organized the curation and preparation of the specimen. P.J.C., J.L., D.K.Z, E.K., and K.C. performed the research, with J.L., D.K.Z., and P.J.C. performing the phylogenetic analysis. D.K.Z., J.L., P.J.C, and M.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and provided input on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Notes and Supplementary References (PDF 986 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Pu, H., Zelenitsky, D., Lü, J. et al. Perinate and eggs of a giant caenagnathid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of central China. Nat Commun 8, 14952 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14952

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14952

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

An Intermediate Incubation Period and Primitive Brooding in a Theropod Dinosaur

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

Reevaluation of the Dentary Structures of Caenagnathid Oviraptorosaurs (Dinosauria, Theropoda)

Scientific Reports (2018)