Abstract

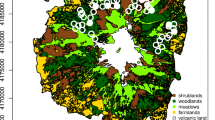

Endangered species recovery requires knowledge of species abundance, distribution, habitat preferences, and threats. Endangered beach mouse populations (Peromyscus polionotus subspp.) occur on barrier islands in Florida and Alabama. Camera traps may supplement current methods and strengthen inferences of animal activity. Between November 2020-February 2022, we conducted 140 camera surveys across 86 track tubes on Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida. We used generalized linear models to explore the relationships between beach mouse detections and environmental factors. We detected beach mice on 6,397 occasions across all tubes. Detections ranged from 0 to 147 observations/survey. Our top model suggested that beach mouse detection was related to cover type with positive associations with grassland and dune compared to scrub. Detections further varied depending on islands, were negatively associated with predator detections, and increased in winter months. Our results suggest that cameras can supplement inference about vegetation associations at broader scales to complement monthly track tube surveys since detection counts are more informative than presence/absence data alone. Given that all tubes exhibited at least one observation, the camera trap network may provide a less frequent and more robust survey method relative to monthly track tube surveys. Adopting such a multifaceted approach may reduce effort and strengthen inference to inform recovery objectives and adaptive management range-wide for all listed beach mouse subspecies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data and R scripts are stored with study authors and available upon request as .csv and .txt files. Given that sites are located on restricted lands operated by the Department of Defense and involve endangered species, original camera trap images are stored on external hard drives and can be available to qualified researchers upon reasonable requests.

References

Barton BT, Roth JD (2007) Raccoon removal on sea turtle nesting beaches. J Wildl Manag 71(4):1234–1237

Bengsen A, Butler J, Masters P (2011) Estimating and indexing feral cat population abundances using camera traps. Wildl Res 38(8):732–739

Blair WF (1951) Population structure, social behavior and environmental relations in a natural population of the beach mouse (Peromyscus polionotus leucocephalus). Contributions from the Laboratory of Vertebrate Biology. Univ Mich 48:1–47

Burger W (2020) Easily overlooked: Modeling Coastal Dune Habitat Occupancy of Threatened and Endangered Beach Mice (Peromyscus Polionotus Spp.) using high-resolution aerial imagery and elevation models of the Northern Gulf of Mexico. Mississippi State University

Cove MV, Simons TR, Gardner B, Maurer AS, O’Connell AF (2017) Evaluating nest supplementation as a management strategy in the recovery of the endangered rodents of the Florida Keys. Restor Ecol 25(2):253–260

Cove MV, Dietz SL, Anderson CT, Jenkins AM, Hooker KR, Kaeser MJ (2024) Endangered beach mouse resistance to a Category 5 hurricane is mediated by elevation and dune habitat. Integrative Conservation

Daly M, Wilson MI and S. F. Faux (1978). Seasonally variable effects of conspecific odors upon capture of deermice (Peromyscus maniculatus Gambelii). Behav Biology 23: 254–259

deRivera CE (2003) Causes of a male-biased operational sex ratio in the fiddler crab Uca crenulata. J Ethol 21:137–144

Evansen M, Carter A, Malcom J (2021) A monitoring policy framework for the United States Endangered species Act. Environ Res Lett 16(3):031001

Fedriani JM, Fuller TK, Sauvajot RM (2001) Does availability of anthropogenic food enhance densities of omnivorous mammals? An example with coyotes in southern California. Ecography 24(3):325–331

Gore JA, Schaefer TL (1993) Distribution and conservation of the Santa Rosa beach mouse. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (Vol. 47, pp. 378–385)

Greene DU, Gore JA, Austin JD (2017) Reintroduction of captive-born beach mice: the importance of demographic and genetic monitoring. J Mammal 98(2):513–522

Holler NR (1992) Choctawhatchee beach mouse. Rare and endangered biota of Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL, pp 76–86

Humphrey SR, Barbour DB (1981) Status and habitat of 3 subspecies of Peromyscus polionotus in Florida. J Mammal 62:840–844

Kays R, Arbogast BS, Baker-Whatton M, Beirne C, Boone HM, Bowler M, Burneo SF, Cove MV, Ding P, Espinosa S, Sousa Gonçalves AL, Hansen CP, Jansen PA, Kolowski JM, Knowles TW, Moreira Lima MG, Millspaugh J, McShea WJ, Pacifici K, Parsons AW, Pease BS, Rovero F, Santiago BN, Santos F, Schuttler SG, Sheil D, Si X, Snider M, Spironello WR (2020) An empirical evaluation of camera trap study design: how many, how long, and when? Methods Ecol Evol 11(6):700–713

Lenth R (2022) emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means_. R package version 1.8.0, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Loggins RE, Gore JA, Brown LL, Slaby LA, Leone EH (2010) A modified track tube for detecting beach mice. J Wildl Manag 74(5):1154–1159

Mabee TJ (1998) A weather-resistant tracking tube for small mammals. Wildl Soc Bull 26:571–574

MacKenzie DI, Nichols JD, Hines JE, Knutson MG, Franklin AB (2003) Estimating site occupancy, colonization, and local extinction when a species is detected imperfectly. Ecology 84(8):2200–2207

McShea WJ, Forrester T, Costello R, He Z, Z., and, Kays R (2016) Volunteer-run cameras as distributed sensors for macrosystem mammal research. Landscape Ecol 31(1):55–66

Moyers JE (1996) Food habits of the Gulf Coast subspecies of beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus spp.). M.S. thesis, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama

Oli MK, Holler NR, Wooten MC (2001) Viability analysis of endangered Gulf Coast beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus) populations. Biol Conserv 97(1):107–118

Pries AJ, Branch LC, Miller DL (2009) Impact of hurricanes on habitat occupancy and spatial distribution of beach mice. J Mammal 90(4):841–850

Robley A, Gormley A, Woodford L, Lindeman M, Whitehead B, Albert R, Bowd M, Smith A (2010) Evaluation of camera trap sampling designs used to determine change in occupancy rate and abundance of feral cats. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research in partnership with Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts

Schwartz MW (2008) The performance of the endangered species act. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 39:279–299

Sollmann R, Mohamed A, Samejima H, Wilting A (2013) Risky business or simple solution - relative abundance indices from camera-trap**. Biol Conserv 159:405–412

Swilling WR, Wooten MC, Holler NR, Lynn WJ (1998) Population dynamics of Alabama beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus ammobates) following Hurricane Opal. Am Midl Nat 140(2):287–298

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2006) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Designation of critical habitat for the Perdido Key Beach Mouse, Choctawhatchee Beach mouse, and St. Andrew Beach Mouse; Final Rule. Fed Reg: 71:60238–60370

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (2010) St. Andrew Beach Mouse Recovery Plan (Peromyscus polionotus peninsularis). Atlanta, Georgia. 95 pp

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (1987) Recovery plan for the Choctawhatchee, Perdido Key, and Alabama Beach Mouse. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Atlanta, Georgia. 45 pp

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (1985) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; determination of endangered status and critical habitat for three beach mice; final rule. Fed Reg 50:23872–23889

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (1989) Endangered status for the Anastasia Island beach mouse and threatened status for the southeastern beach mouse; final rule. Fed Reg 54:20598–20602

United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) (1998) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; determination of endangered status for the St. Andrew beach mouse; final rule. Fed Reg 63:70053–70062

Wilkinson EB, Branch LC, Miller DL, Gore JA (2012) Use of track tubes to detect changes in abundance of beach mice. J Mammal 93(3):791–798

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff that monitored these populations of beach mice and maintained the tracking tube grid over the many years of this study. Thanks to Ashley Warren with U.S. National Park Service for assistance with field sampling.

Funding

This research and publication were funded by a cooperative agreement between the Florida Natural Areas Inventory and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K. Hooker: Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Writing-original & review. M. Cove: Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Data curation, Writing-original & review. E. C. Watersmith: Data curation, Methodology, Writing- review. A. Jenkins: Data collection, Conceptualization, Methodology, I. Hodges: Data collection, Methodology, D. Seay: Data collection, Methodology, M. Kaeser: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing- review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by: Karol Zub.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hooker, K.R., Cove, M.V., Watersmith, E.C. et al. Camera traps strengthen inference about endangered beach mouse activity. Mamm Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-024-00752-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-024-00752-3