Abstract

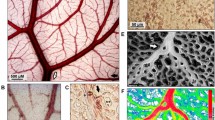

In chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, inflammatory edema drives tissue remodeling favoring anomalous growth of the nasal mucosa, but a proangiogenic contribution of nasal polyp in support of tissue growth is still controversial. The chorioallantoic membrane of chicken embryo model was employed to address the potentiality of nasal tissue fragments to modulate angiogenesis. Fifty-seven fertilized eggs were implanted with polyp or healthy nasal mucosa tissue or were kept as non-implanted controls. The embryos’ size, length, and development stage, and chorioallantoic membrane vasculature morphology were evaluated after 48 h. Quantitative computer vision techniques applied to digital chorioallantoic membrane images automatically calculated the branching index as the ratio between the areas of the convex polygon surrounding the vascular tree and the vessels’ area. Ethics approval and consent to participate: the study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (CAAE number: 80763117.1.0000.5505) and by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of University of São Paulo (nº CEUA 602–2019). Mucosal, but not polyp tissue implants, hampered embryo development and induced underdeveloped chorioallantoic membranes with anastomosed, interrupted, and regressive vessels. Vessels’ areas and branching indexes were higher among the chorioallantoic membranes with polyp implants and controls than among those with healthy mucosa implants. Nasal polyp presents differential angiogenic induction that impacts tissue growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hedman J, Kaprio J, Poussa T et al (1999) Prevalence of asthma, aspirin intolerance, nasal polyposis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a population-based study. Int J Epidemiol 28:717–722

Rinia AB, Kostamo K, Ebbens FA et al (2007) Review article: nasal polyposis: a cellular-based approach to answering questions. Allergy 62:348–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01323.x

Pezato R, Voegels R, Pinto Bezerra T et al (2014) Mechanical dysfunction in the mucosal oedema formation of patients with nasal polyps. Rhinology 52:162–166. https://doi.org/10.4193/Rhin13.066

Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C et al (2020) European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology 58:1–464

Zhu H, Sun N, Wang Y et al (2018) Inflammatory infiltration and tissue remodeling in nasal polyps and adjacent mucosa of unaffected sinus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 11:2707–2713

Pezato R, Balsalobre L, Lima M et al (2013) Convergence of two major pathophysiologic mechanisms in nasal polyposis: immune response to staphylococcus aureus and airway remodeling. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 42:27

Pezato R, Voegels RL, Pignatari S et al (2019) Nasal polyposis: more than a chronic inflammatory disorder—a disease of mechanical dysfunction—the São Paulo position. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676659

Gregório L, Pezato R, Felici RS et al (2017) Fibrotic tissue and middle turbinate exhibit similar mechanical properties. Is fibrosis a solution in nasal polyposis? Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 21:122–125. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1593728

Balsalobre L, Pezato R, Mangussi-Gomes J et al (2019) What is the impact of positive airway pressure in nasal polyposis? An experimental study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 23:147–151

Pezato R, Almeida DCd, Bezerra TF et al (2014) Immunoregulatory effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the nasal polyp microenvironment. Mediat Inflamm 2014:11

Pezato R, Gregorio L, Voegels R et al (2016) Hypotheses about the potential role of mesenchymal stem cell on nasal polyposis: a soft inflamed tissue suffering from mechanical dysfunction. Austin Immunol 1:1004

de Oliveira PWB, Pezato R, Agudelo JSH et al (2017) Nasal polyp-derived mesenchymal stromal cells exhibit lack of immune-associated molecules and high levels of stem/progenitor cells markers. Front Immunol 8:39

Widdicombe JG (1990) Comparison between the vascular beds of upper and lower airways. Eur Respir J Suppl 12:564s–571s

Ribatti D, Nico B, Vacca A et al (2001) Chorioallantoic membrane capillary bed: a useful target for studying angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis in vivo. Anat Rec 264:317–324

Nowak-Sliwinska P, Segura T, Iruela-Arispe ML (2014) The chicken chorioallantoic membrane model in biology, medicine and bioengineering. Angiogenesis 17:779–804

Ribatti D (2010) The chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane in the study of angiogenesis and metastasis: the CAM assay in the study of angiogenesis and metastasis. Springer, Netherlands

Herrmann A, Moss D, Sée V (2016) The chorioallantoic membrane of the chick embryo to assess tumor formation and metastasis. Methods Mol Biol 1464:97–105

Coleman CM (2008) Chicken embryo as a model for regenerative medicine. Birth defects research. Part C Embryo Today 84:245–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrc.20133

Baldavira CM, Gomes LF, Cruz LT et al (2021) In vivo evidence of angiogenesis inhibition by β2-glycoprotein I subfractions in the chorioallantoic membrane of chicken embryos. Braz J MedBiol Res 54:e10291

Pereira Lopes J, Barbosa M, Stella C et al (2010) In vivo anti-angiogenic effects further support the promise of the antineoplasic activity of methyl jasmonate. Braz J Biol 70:443–449

Hamburger V, Hamilton HL (1992) A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. Dev Dyn 195:231–272

Machado C, Nicot ME, Stella CN et al (2013) Digital image processing assessment of the differential in vitro antiangiogenic effects of dimeric and monomeric Beta2-Glycoprotein I. J Cytol Histol 4:1–8

Pereira Lopes JE, Barbosa MR, Stella CN et al (2010) In vivo anti-angiogenic effects further support the promise of the antineoplasic activity of methyl jasmonate. Braz J Biol 70:443–449

Glantz S (2012) Primer of biostatistics. McGraw-Hill, New York

Jones TA, Jones SM, Paggett KC (2006) Emergence of hearing in the chicken embryo. J Neurophysiol 96:128–141

Nowak-Sliwinska P, Alitalo K, Allen E et al (2018) Consensus guidelines for the use and interpretation of angiogenesis assays. Angiogenesis 21:425–532

Ogasawara N, Poposki JA, Klingler AI et al (2020) Role of RANK-L as a potential inducer of ILC2-mediated type 2 inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Mucosal Immunol 13:86–95

Morales M (2008) Alternative methods to the use of animals in scientific research: myth or reality? Cienc Cult 60:33–36

Dos Santos JA, Duailibi MT, Maria DA et al (2018) Chick embryo model for homing and host interactions of tissue engineering-purposed human dental stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 24:882–888

Stern CD (2005) The chick; a great model system becomes even greater. Dev Cell 8:9–17

Yalcin HC, Shekhar A, Rane AA et al (2010) An ex-ovo chicken embryo culture system suitable for imaging and microsurgery applications. J Vis Exp 44:2154

Boucher Y, Baxter LT, Jain RK (1990) Interstitial pressure gradients in tissue-isolated and subcutaneous tumors: implications for therapy. Cancer Res 50:4478–4484

Gilbert S (2006) Developmental biology. Page Publishers, Sunderland, MA

Bolger WE, Butzin CA, Parsons DS (1991) Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT analysis for endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope 101:56–64

Nonaka M, Pawankar R, Saji F et al (1999) Distinct expression of RANTES and GM-CSF by lipopolysaccharide in human nasal fibroblasts but not in other airway fibroblasts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 119:314–321

Comşa Ş, Ceaușu RA, Popescu R et al (2017) The human mesenchymal stem cells and the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane: the key and the lock in revealing vasculogenesis. in vivo 31:1139–1144

Tickle C, Münsterberg A (2001) Vertebrate limb development–the early stages in chick and mouse. Curr Opin Genet Dev 11:476–481

Martin G (2001) Making a vertebrate limb: new players enter from the wings. Bioessays 23:865–868

Özkalaycı F, Gülmez Ö, Uğur-Altun B et al (2018) The role of osteoprotegerin as a cardioprotective versus reactive inflammatory marker: the chicken or the egg paradox. Balkan Med J 35:225–232

Pisati F, Belicchi M, Acerbi F et al (2007) Effect of human skin-derived stem cells on vessel architecture, tumor growth, and tumor invasion in brain tumor animal models. Cancer Res 67:3054–3063

Francki A, Labazzo K, He S et al (2016) Angiogenic properties of human placenta-derived adherent cells and efficacy in hindlimb ischemia. J Vasc Surg 64:746–756e741

Funding

the authors declare that they received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

We confirm that all of the listed authors meet the criteria for authorship and originality and that none of the material in the manuscript is included in another manuscript, have been published previously, or are currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

de Góes, H.A.N., Sarafan, M., do Amaral, J.B. et al. Differential Angiogenic Induction Impacts Nasal Polyp Tissue Growth. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 75 (Suppl 1), 893–900 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-03469-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-023-03469-y