Abstract

Aims

The extent and persistence of pre-Columbian human legacies in old-growth Amazonian forests are still controversial, partly because modern societies re-occupied old settlements, challenging the distinction between pre- and post-Columbian legacies. Here, we compared the effects of pre-Columbian vs. recent landscape domestication processes on soils and vegetation in two Amazonian regions.

Methods

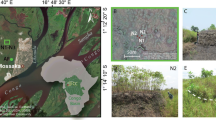

We studied forest landscapes at varying distances from pre-Columbian and current settlements inside protected areas occupied by traditional and indigenous peoples in the lower Tapajós and the upper-middle Madeira river basins. By conducting 69 free-listing interviews, participatory map**s, guided-tours, 27 forest inventories, and soil analysis, we assessed the influences of pre-Columbian and current activities in soils and plant resources surrounding the settlements.

Results

In both regions, we found that pre-Columbian villages were more densely distributed across the landscape than current villages. Soil nutrients (mainly Ca and P) were higher closer to pre-Columbian villages but were generally not related to current villages, suggesting past soil fertilization. Soil charcoal was frequent in all forests, suggesting frequent fire events. The density of domesticated plants used for food increased in phosphorus enriched soils. In contrast, the density of plants used for construction decreased near current villages.

Conclusions

We detected a significant effect of past soil fertilization on food resources over extensive areas, supporting the hypothesis that pre-Columbian landscape domestication left persistent marks on Amazonian landscapes. Our results suggest that a combination of pre-Columbian phosphorus fertilization with past and current management drives plant resource availability in old-growth forests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The extraordinary capacity of human societies to domesticate landscapes has promoted global alterations in natural ecological processes, ecosystems and species distributions (Boivin et al. 2016). Landscape domestication is defined as a continuum of land transformations by humans extending from semi-natural landscapes to cultivated lands and densely settled areas (Clement 1999; Ellis 2015; Clement and Cassino 2018) in which human manipulation of species populations and soil properties resulted in more secure and productive areas (Clement 1999; Erickson 2008). Evidence of landscape domestication has been found in extensive areas that - to the untrained eye - may seem natural (van Gemerden et al. 2003; Dambrine et al. 2007; Ross 2011; Levis et al. 2017). For instance, previous studies have shown that species richness and soil nutrients increase near ancient Roman settlements abandoned for millennia (Dambrine et al. 2007). Similarly, soil phosphorus and calcium are significantly higher in old habitation sites of the First Nations along the British Columbian Coast (Trant et al. 2016). In Mesoamerican forests, a higher abundance of plant species used by Maya people for daily needs persists in densely-settled forest areas even after centuries of human abandonment (Ross 2011). In southern Amazonia, a mosaic of domesticated landscapes was detected in an area of approximately 50,000 km2 in the Upper ** and complemented with the information collected during guided tours. With guided tours we validated the location of most ADE sites. Some sites near the Tapajós were mapped by Schaan et al. (2015). Altitude varies among forest plots in the Madeira River basin (80–110 m) and in the Tapajós River basin (150–200 m), and this variation was detected using SRTM (Shuttle Radar Topography Mission) images available at http://www.dsr.inpe.br/topodata/

Four of six villages - two in the FLONA Tapajós and two in the FLONA Humaitá - are inhabited by traditional societies, and two villages are in the Jiahui Indigenous Land. Traditional societies have existed for at least 100 years; most of them are descendants of migrants who intermarried with local indigenous peoples, but they are not members of an indigenous group. Inhabitants of Jiahui Indigenous Land are members of the Jiahui indigenous group that speak a Tupi-Guarani language (Peggion 2006). Traditional societies and the Jiahui indigenous group regularly practice farming, fishing, hunting, timber and non-timber forest product extraction, and, in the case of the FLONA Tapajós, the villages are also involved in community-based tourism. In this study, we defined current villages as the areas currently inhabited (most were established approximately 120 years ago) and pre-Columbian villages as the sites with ADE, which are likely older than 350 years (de Souza et al. 2019).

Although all archaeological sites mapped in both regions contain ADE sites with ceramics, which indicate sedentary pre-Columbian occupation (Neves et al. 2003), the ancient histories of the regions differ. Archaeological sites of the lower Tapajós River basin are mainly associated with the Tapajó or Santarém pottery, which is affiliated with the Incised and Punctate tradition (Stenborg 2016; Figueiredo 2019), while many sites in the middle-upper Madeira River basin are multi-componential, with the most recent layer containing the Polychrome pottery tradition (Moraes and Neves 2012; Barreto et al. 2016). Before this study, 148 archaeological sites had been recorded in the lower Tapajós River basin, in an area of 10,000 km2, including 13 sites inside the FLONA Tapajós (e.g., Schaan et al. 2015; Stenborg, 2016; Stenborg et al. 2018; Figueiredo 2019). Almost 70% of these archaeological sites are located on the interfluve (away from major Amazonian rivers), 6% are located on hillsides, and only 24% are located along the Tapajós River, secondary rivers and lakes (Stenborg et al. 2018). Despite the abundance of archaeological sites in interfluvial areas, riverside settings have a longer occupation history, likely starting about 4300 cal BP (calibrated years Before Present) (Maezumi et al. 2018a). Pre-Columbian activities intensified around 1250 cal BP and remained until European conquest and subsequent colonization (500 cal BP, Maezumi et al. 2018a). In contrast to the lower Tapajós River region, archaeological sites of the upper-middle Madeira River near Humaitá were poorly described and few sites were mapped before this study. However, the occupation of the upper Madeira River basin is much older than of the lower Tapajós, starting around 12,000 BP (Miller 1992) and intensified around 1000 BP when the Polychrome pottery tradition expanded along the Madeira (Moraes and Neves 2012). The expansion of this tradition has been likely associated with the expansion of Tupi speaking groups (Barreto et al. 2016).

Management practices probably intensified when human populations expanded around a thousand years ago in both river basins (Levis et al. 2018). After European conquest, indigenous populations collapsed and a new wave of human expansion occurred during the rubber boom (in the late nineteenth century), when both the Tapajós and Madeira basins were occupied by their current inhabitants. Management activities that occurred during this period may also have influenced forest structure and composition, since local people mentioned that at that time they used forests more extensively than they do today. In the last century, people have favoured the development of rubber agroforests by actively planting rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) in their manioc fields and managing them in fallows that became agroforests (Schroth et al. 2003).

Ethnoecological and archaeological methods

In each village we conducted the following activities: (1) free listing interviews with 33 key informants in the FLONA Tapajós, 24 in the FLONA Humaitá and 12 in the Jiahui Indigenous Land about which trees and palms are useful for them, their types of uses, and the forest management activities related to these plants; (2) participatory map** and guided tours along 80 km of trails in the Tapajós with the seven most experienced informants and approximately 115 km of trails in the Madeira with the 15 most experienced informants to describe the extension of their activities in the forest and the location of currently unoccupied ADE sites, and to identify the plants they currently manage in the forest; and (3) 27 forest inventory plots randomly placed at different distances from current and pre-Columbian villages. We used snowball sampling techniques to find informants who know and use forest species (Albuquerque et al. 2014), and collected the GPS points of all ADE sites and of useful plants cited in the interviews. In total we interviewed 24 men and 9 women in the Flona Tapajós, whose ages varied from 25 to 83 years; 20 men and 4 women in the Flona Humaitá, whose ages varied from 19 to 68 years; and 10 men and 2 women in the Jiahui Indigenous Land, whose ages varied from 18 to 85 years. For more details about these ethnoecological methods see Cassino et al. (2019).

Based on local knowledge and previous study (Levis et al. 2017), we created four categories of useful plants. Useful plants were defined as species that have been used for any reason in the past or are currently used by local people. First, we classified all useful plants into two categories: 1) useful plants that are not managed; and 2) useful plants that are managed today (see Levis et al. 2018 for more details about the management categories). Within the currently managed plants, we categorized a third group of plants that are more intensively managed, because people occasionally plant them in cultivated landscapes, here called cultivated plants. Because plant domestication is long-term process that is difficult to detect using only local interviews, we used the literature to determine which species have populations with some degree of domestication reported somewhere in Amazonia (Levis et al. 2017) and created a fourth category of useful plants, namely domesticated plants. As we wanted to compare pre-Columbian and post-Columbian impacts on forest resources, our analyses focused on useful and domesticated plants.

Inside the FLONA Tapajós, the extension of the pre-Columbian villages (ADE) in most of the sites was measured with the assistance of a member of the community and handheld GPS. In addition, in two ADE sites, shovel test pits supervised by an archaeologist (coauthor CGF) were excavated in two transects to delimit their extension. Handheld GPS and Google Earth images were also used to map the area occupied by current houses and homegardens in the villages we worked with (Maguarí and Jamaraquá). In the Madeira basin, we could not measure the size of the ADE sites because of logistical limitations.

We also calculated the density of pre-Columbian and current villages that occur in the study area in both basins and the distance from these villages to major rivers, perennial rivers and streams. We used all rivers of the HydroSHEDS dataset to define streams and “upcell” values greater than 15,000 to define perennial rivers of approximately 10 m width, following the study of McMichael et al. (2014). We estimated study area in both basins based on the extension of the local people’s activities in the forest described during participatory map** and guided-tours: 12,400 ha in the Flona Tapajós; 15,800 ha in the Flona Humaitá; 25,600 ha in the Jiahui Land.

Forest inventories

We randomly sampled forest plots of 0.5 ha (50 × 100 m) at different distances from pre-Columbian (0–4.1 km) and current villages (0.9–15.4 km). Plots were restricted to old-growth forest on terra-firme terrain located on plateaus in both basins (Fig. 1b-c). We did not sample forests located more than 4 km from pre-Columbian sites, because the mean distance we found between pairs of sites in the Madeira study area is 5 km and in the Tapajós study area is 2 km. To sample the plots at different distances from pre-Columbian villages, we created buffers around the ADE sites, differing in size (0–1, 1–2, 2–4 km), based on land use zones described in a previous study (Heckenberger et al. 2008). We used these buffer classes to randomly sample one location for our inventory plot per pre-Columbian village per buffer zone. We selected a location for the plot where the buffers did not overlap more than 50% with a neighbouring buffer class. Distances and buffers were established based on the information of ADE sites gathered from participatory map** and with GPS during guided tours, and were mapped with QGIS 2.18.25 software.

During the plot inventories, trees and palms with diameters at breast height (dbh) ≥ 1 cm were sampled in sub-plots of 0.01 ha, trees and palms with dbh ≥ 10 cm were sampled in sub-plots of 0.25 ha, and trees and palms with dbh ≥ 30 cm were sampled in the full 0.5 ha plot. We counted and measured the diameter of all living trees and palms present in the plot, but we only identified and collected botanical vouchers for useful species with vernacular names listed in the interviews. Botanical identification was based on the Species List of the Flora do Brazil available at http://www.floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br. The vouchers were deposited at the INPA Herbarium, the UFOPA Herbarium, and the EAFM Herbarium. For the analysis, we used the vernacular names given by informants because these are the units that people actually use and manage. Some vernacular names refer to single botanical species, but others refer to a group of botanical species that share similar traits, and which often belong to the same botanical genus or family (Berlin 1992).

Soil data

To detect human effects on forest soils and to identify fire events, we used a post-hole digger to collect soils and pieces of charcoal in three locations along the central plot line from 0 to 40 cm depth. Sample points cover a gradient from dark soils and dark-brown soils to yellow-brown soils. Pieces of charcoal visible to the naked eye were quantified every 10 cm of the 0 to 40 cm samples done in each of the three locations per plot; frequency of charcoal was calculated by the presence/absence of these pieces in each point at each depth, so 100% frequency is charcoal presence at all 12 points/depths per plot. We also measured the frequency of soil charcoal below 20 cm and above 20 cm and found that the frequencies of charcoal in these two soil layers were highly correlated (Spearman’s rank correlation = 0.71, p < 0.001). Due to lack of funding we could not date the charcoal found in our samples, but as suggested in the literature we assumed that charcoal above 20 cm is more likely to be associated with modern fires and below this layer is more likely to be associated with pre-Columbian fires (McMichael et al. 2012). ADE sites in the Flona Tapajós were dated between 3362 and 3160 cal BP to 666–622 and 612–559 cal BP (Figueiredo 2019), and 530–450 cal BP (Maezumi et al. 2018a). Also, ADE sites across Amazonia are likely older than 350 years BP according to the literature review of de Souza et al. (2019).

Only soil samples from 0 to 30 cm depth were dried and analysed in the Plant and Soil Thematic Laboratory at INPA for chemical and physical properties. Total phosphorus was determined by acid digestion using concentrated sulphuric acid (Quesada et al. 2010) and available phosphorus was determined by Mehlich I Teixeira et al. (2017). Exchangeable Ca, Mg, K, Na and Al were determined by the silver thiourea method (Pleysier and Juo 1980). Organic carbon was determined by Walkley and Black (1934), and pH was analysed in water at 1: 2.5 ml. The percentage of sand, silt and clay was also calculated following (Teixeira et al. 2017).

Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in the R platform (3.5.1, R Development Core Team 2018). To evaluate if pre-Columbian and current villages were equally distributed along major rivers, perennial rivers and streams, we measured the minimum linear distances between villages and from villages to all river types using the “NNJoin” tool of QGIS version 2.18.25. As proxies for the intensity of human activities in forest plots, we measured the walking distance from forest plots to the current villages (in kilometers - km) and the linear distance from forest plots to pre-Columbian villages (km), because we don’t know where pre-Columbian pathways were located.

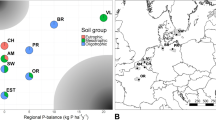

We explored the variability of soil chemical and physical variables across forest plots using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on a correlation matrix. Soil variables with skewed distributions (total P, available P, Ca, Mg) were log-transformed (log10 + 1). We included only the percentage of clay and sand in the PCA, because texture variables sum to 100%, which means they are complementary. The PCA was used to evaluate the spatial distribution of soil properties and help identify the soil variables that are most associated with the variation in soil fertility.

To understand how pre-Columbian and current human activities have influenced forest soils, forest structure and forest resources we used structural equation modelling (SEM). SEM is based on multiple regression equations, and can be used to test indirect and direct effects and investigate causality between variables (Grace et al. 2010). To do so, we defined a priori SEM models including the direct and indirect effects of human activities and edaphic factors on forest structure and forest resource variables (Fig. S1), and the models were adjusted if necessary (Grace et al. 2010). Correlations among factors are considered and reported when significant correlations are detected. Because we defined models a priori in SEM, the models are considered to be statistically accepted when they cannot be rejected (p > 0.05), meaning that the proposed relationships accurately describe the data. We ran separate models to understand how forest structure variables (stand basal area, density of canopy stems and density of sub-canopy stems) and forest resource variables (relative basal area and relative density of useful and domesticated plants used for food and construction) are related to the four fixed predictor variables: distance from plots to pre-Columbian villages, distance from plots to current villages, soil phosphorus, and soil charcoal (0–40 cm) (Fig. S1). The sum of all stems with dbh ≥ 1 cm was calculated to define the density of sub-canopy stems in 1 ha and the sum of all stems with dbh ≥ 10 cm was calculated to define the density of canopy stems in 1 ha. The stand basal area (BA) is the sum of the basal area of all stems with dbh ≥ 10 cm in 1 ha because sub-canopy stems make a small contribution to BA. Basin (Tapajós and Madeira) was incorporated as a random factor in all models; because samples within the same region share similar characteristics as they share similar environments and we wanted to account for the spatial aggregation of our data within basins.

Structural equation models were created using mixed-linear models, which were evaluated using the “lme” function of the “nlme” package (Pinheiro et al. 2018) and performed using the “psem” function of the piecewise SEM package (Lefcheck 2016). The PCA analysis was run using the “prcomp” function and visualized using the “autoplot” function of the “ggfortify” package (Tang et al. 2016). Conditional plots were used to visualize the mixed-effect models using the “visreg” package (Breheny and Burchett 2017).