Abstract

Cardiac positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has established themselves firmly as excellent and reliable functional imaging modalities in assessment of the spectrum of coronary artery disease. With the explosion of technology advances and the dream of flow quantification now a reality, the value of PET is now well realized. Cardiac PET has proved itself as precise imaging modality that provides functional imaging of the heart in addition to anatomical imaging. It has established itself as one of the best available techniques for evaluation of myocardial viability. Hybrid PET/computed tomography provides simultaneous integration of coronary anatomy and function with myocardial perfusion and metabolism, thereby improving characterization of the dysfunctional area and chronic coronary artery disease. The availability of quantitative myocardial blood flow evaluation with PET provides additional prognostic information and increases diagnostic accuracy in the management of patients with coronary artery disease. Hybrid imaging seems to hold immense potential in optimizing management of cardiovascular diseases and furthering clinical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Ter-Pogossian MM, Phelps ME, Hoffman EJ, Mullani NA (1975) A positron-emission transaxial tomograph for nuclear imaging (PETT). Radiology 114:89–98

Gaemperli O, Kaufmann PA (2011) PET and PET/CT in cardiovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1228:109–136

Townsend DW (2008) Positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Semin Nucl Med 38:152–166

Robson PM, Dey D, Newby DE et al (2017) MR/PET imaging of the cardiovascular system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 10:1165–1179

Klein C, Nekolla SG, Bengel FM et al (2002) Assessment of myocardial viability with contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with positron emission tomography. Circulation 105:162–167

Schwitter J, DeMarco T, Kneifel S et al (2000) Magnetic resonance-based assessment of global coronary flow and flow reserve and its relation to left ventricular functional parameters: a comparison with positron emission tomography. Circulation 101:2696–2702

Boyd DP (2007) Instrumentation and principles of CT. In: Di Carli MF, Lipton MJ (eds) Cardiac PET and PET/CT Imaging. Springer, New York, pp 19–33

Slart R, Glaudemans A, Gheysens O et al (2021) Procedural recommendations of cardiac PET/CT imaging: standardization in inflammatory-, infective-, infiltrative-, and innervation (4Is)-related cardiovascular diseases: a joint collaboration of the EACVI and the EANM. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48:1016–1039

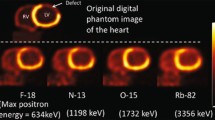

Araujo LI, Lammertsma AA, Rhodes CG et al (1991) Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial blood flow in coronary artery disease with oxygen-15-labeled carbon dioxide inhalation and positron emission tomography. Circulation 83:875–885

Schelbert HR, Phelps ME, Hoffman EJ, Huang SC, Selin CE, Kuhl DE (1979) Regional myocardial perfusion assessed with N-13 labeled ammonia and positron emission computerized axial tomography. Am J Cardiol 43:209–218

Herrero P, Markham J, Shelton ME, Weinheimer CJ, Bergmann SR (1990) Noninvasive quantification of regional myocardial perfusion with rubidium-82 and positron emission tomography. Exploration of a mathematical model Circulation 82:1377–1386

Nekolla SG, Reder S, Saraste A et al (2009) Evaluation of the novel myocardial perfusion positron-emission tomography tracer 18F-BMS-747158-02: comparison to 13N-ammonia and validation with microspheres in a pig model. Circulation 119:2333–2342

Maddahi J, Czernin J, Lazewatsky J et al (2011) Phase I, first-in-human study of BMS747158, a novel 18F-labeled tracer for myocardial perfusion PET: dosimetry, biodistribution, safety, and imaging characteristics after a single injection at rest. J Nucl Med 52:1490–1498

Veltman CE, de Wit-van der Veen BJ, de Roos A, Schuijf JD et al (2013) Myocardial perfusion imaging: the role of SPECT, PET and CMR. In: Marzullo P, Mariani G, eds. From Basic Cardiac Imaging to Image Fusion: Core Competencies Versus Technological Progress. Milan: Springer; 2013:29–49.

Yoshida K, Mullani N, Gould KL (1996) Coronary flow and flow reserve by PET simplified for clinical applications using rubidium-82 or nitrogen-13-ammonia. J Nucl Med 37:1701–1712

Lecomte R (2004) Technology challenges in small animal PET imaging. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A 527:157–165

Yoshinaga K, Klein R, Tamaki N (2010) Generator-produced rubidium-82 positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging-From basic aspects to clinical applications. J Cardiol 55:163–173

Yu M, Guaraldi MT, Mistry M et al (2007) BMS-747158-02: a novel PET myocardial perfusion imaging agent. J Nucl Cardiol 14:789–798

Krivokapich J, Huang SC, Selin CE, Phelps ME (1987) Fluorodeoxyglucose rate constants, lumped constant, and glucose metabolic rate in rabbit heart. Am J Physiol 252:H777-787

Kazakauskaite E, Zaliaduonyte-Peksiene D, Rumbinaite E, Kersulis J, Kulakiene I, Jurkevicius R (2018) Positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and management of coronary artery disease. Medicina (Kaunas) 54:47

Al Badarin FJ, Malhotra S (2019) Diagnosis and prognosis of coronary artery disease with SPECT and PET. Curr Cardiol Rep 21:57

Schindler TH, Zhang XL, Vincenti G, Mhiri L, Lerch R, Schelbert HR (2007) Role of PET in the evaluation and understanding of coronary physiology. J Nucl Cardiol 14:589–603

Camici PG, Crea F (2007) Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 356:830–840

Schindler TH, Facta AD, Prior JO et al (2009) Structural alterations of the coronary arterial wall are associated with myocardial flow heterogeneity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 36:219–229

Shaw LJ, Min JK, Hachamovitch R et al (2010) Cardiovascular imaging research at the crossroads. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 3:316–324

Dorbala S, Vangala D, Sampson U, Limaye A, Kwong R, Di Carli MF (2007) Value of vasodilator left ventricular ejection fraction reserve in evaluating the magnitude of myocardium at risk and the extent of angiographic coronary artery disease: a 82Rb PET/CT study. J Nucl Med 48:349–358

Lertsburapa K, Ahlberg AW, Bateman TM et al (2008) Independent and incremental prognostic value of left ventricular ejection fraction determined by stress gated rubidium 82 PET imaging in patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol 15:745–753

Berman DS, Kang X, Slomka PJ et al (2007) Underestimation of extent of ischemia by gated SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with left main coronary artery disease. J Nucl Cardiol 14:521–528

Gould KL (2009) Coronary flow reserve and pharmacologic stress perfusion imaging: beginnings and evolution. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2:664–669

Tio RA, Dabeshlim A, Siebelink HM et al (2009) Comparison between the prognostic value of left ventricular function and myocardial perfusion reserve in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Nucl Med 50:214–219

Dayanikli F, Grambow D, Muzik O, Mosca L, Rubenfire M, Schwaiger M (1994) Early detection of abnormal coronary flow reserve in asymptomatic men at high risk for coronary artery disease using positron emission tomography. Circulation 90:808–817

Adenaw N, Salerno M (2013) PET/MRI: current state of the art and future potential for cardiovascular applications. J Nucl Cardiol 20:976–989

Valenta I, Quercioli A, Schindler TH (2014) Diagnostic value of PET-measured longitudinal flow gradient for the identification of coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7:387–396

Schneider JF, Thomas HE Jr, Sorlie P, Kreger BE, McNamara PM, Kannel WB (1981) Comparative features of newly acquired left and right bundle branch block in the general population: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol 47:931–940

Vernooy K, Verbeek XA, Peschar M et al (2005) Left bundle branch block induces ventricular remodelling and functional septal hypoperfusion. Eur Heart J 26:91–98

Hayat SA, Dwivedi G, Jacobsen A, Lim TK, Kinsey C, Senior R (2008) Effects of left bundle-branch block on cardiac structure, function, perfusion, and perfusion reserve: implications for myocardial contrast echocardiography versus radionuclide perfusion imaging for the detection of coronary artery disease. Circulation 117:1832–1841

Hoefflinghaus T, Husmann L, Valenta I et al (2008) Role of attenuation correction to discriminate defects caused by left bundle branch block versus coronary stenosis in single photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging. Clin Nucl Med 33:748–751

Vaduganathan P, He ZX, Raghavan C, Mahmarian JJ, Verani MS (1996) Detection of left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis in patients with left bundle branch block: exercise, adenosine or dobutamine imaging? J Am Coll Cardiol 28:543–550

Falcao A, Chalela W, Giorgi MC et al (2015) Myocardial blood flow assessment with 82rubidium-PET imaging in patients with left bundle branch block. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 70:726–732

Ghotbi AA, Kjaer A, Hasbak P (2014) Review: comparison of PET rubidium-82 with conventional SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 34:163–170

Cremer P, Brunken R, Menon V, Cerqueira M, Jaber W (2015) Septal perfusion abnormalities are common in regadenoson spect myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) but Not PET MPI in patients with left bundle branch block (LBBB) [abstract]. J Am Coll Cardiol 65:A1148

Vidula MK, Wiener P, Selvaraj S et al (2021) Diagnostic accuracy of SPECT and PET myocardial perfusion imaging in patients with left bundle branch block or ventricular-paced rhythm. J Nucl Cardiol 28:981–988

Arasaratnam P, Ayoub C, Klein R, DeKemp R, Beanlands RS, Chow BJW (2014) Positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging for diagnosis and risk stratification in obese patients. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 8:9304

Machac J (2005) Cardiac positron emission tomography imaging. Semin Nucl Med 35:17–36

Ghanem MA, Kazim NA, Elgazzar AH (2011) Impact of obesity on nuclear medicine imaging. J Nucl Med Technol 39:40–50

Mc Ardle BA, Dowsley TF, deKemp RA, Wells GA, Beanlands RS (2012) Does rubidium-82 PET have superior accuracy to SPECT perfusion imaging for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary disease?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1828–1837

Freedman N, Schechter D, Klein M, Marciano R, Rozenman Y, Chisin R (2000) SPECT attenuation artifacts in normal and overweight persons: insights from a retrospective comparison of Rb-82 positron emission tomography and TI-201 SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. Clin Nucl Med 25:1019–1023

Bateman TM, Heller GV, McGhie AI et al (2006) Diagnostic accuracy of rest/stress ECG-gated Rb-82 myocardial perfusion PET: comparison with ECG-gated Tc-99m sestamibi SPECT. J Nucl Cardiol 13:24–33

Klodas E, Miller TD, Christian TF, Hodge DO, Gibbons RJ (2003) Prognostic significance of ischemic electrocardiographic changes during vasodilator stress testing in patients with normal SPECT images. J Nucl Cardiol 10:4–8

Chow BJ, Dorbala S, Di Carli MF et al (2014) Prognostic value of PET myocardial perfusion imaging in obese patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 7:278–287

Beanlands RS, Nichol G, Huszti E et al (2007) F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging-assisted management of patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction and suspected coronary disease: a randomized, controlled trial (PARR-2). J Am Coll Cardiol 50:2002–2012

Cleland JG, Calvert M, Freemantle N et al (2011) The Heart Failure Revascularisation Trial (HEART). Eur J Heart Fail 13:227–233

Bonow RO, Maurer G, Lee KL et al (2011) Myocardial viability and survival in ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med 364:1617–1625

Shah BN, Khattar RS, Senior R (2013) The hibernating myocardium: current concepts, diagnostic dilemmas, and clinical challenges in the post-STICH era. Eur Heart J 34:1323–1336

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD et al (2016) 2016 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 69:1167

Ling LF, Marwick TH, Flores DR et al (2013) Identification of therapeutic benefit from revascularization in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: inducible ischemia versus hibernating myocardium. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6:363–372

Barnes E, Dutka DP, Khan M, Camici PG, Hall RJ (2002) Effect of repeated episodes of reversible myocardial ischemia on myocardial blood flow and function in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282:H1603-1608

Wijns W, Vatner SF, Camici PG (1998) Hibernating myocardium. N Engl J Med 339:173–181

Namdar M, Rager O, Priamo J et al (2018) Prognostic value of revascularising viable myocardium in elderly patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction: a PET/CT study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 34:1673–1678

Quail MA, Sinusas AJ (2017) PET-CMR in heart failure - synergistic or redundant imaging? Heart Fail Rev 22:477–489

Gewirtz H (2011) Cardiac PET: a versatile, quantitative measurement tool for heart failure management. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 4:292–302

Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Gistri R, Lorenzoni R, Chiriatti G, Camici PG (2003) Coronary microvascular dysfunction and prognosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 349:1027–1035

Beanlands RS, deKemp R, Scheffel A et al (1997) Can nitrogen-13 ammonia kinetic modeling define myocardial viability independent of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose? J Am Coll Cardiol 29:537–543

Abraham A, Nichol G, Williams KA et al (2010) 18F-FDG PET imaging of myocardial viability in an experienced center with access to 18F-FDG and integration with clinical management teams: the Ottawa-FIVE substudy of the PARR 2 trial. J Nucl Med 51:567–574

Thackeray JT, Bengel FM (2013) Assessment of cardiac autonomic neuronal function using PET imaging. J Nucl Cardiol 20:150–165

Fallavollita JA, Heavey BM, Luisi AJ Jr et al (2014) Regional myocardial sympathetic denervation predicts the risk of sudden cardiac arrest in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:141–149

Schatka I, Bengel FM (2014) Advanced imaging of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med 55:99–106

Terasaki F, Azuma A, Anzai T et al (2019) JCS 2016 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis - digest version. Circ J 83:2329–2388

Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F et al (2014) HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm 11:1305–1323

Kim SJ, Pak K, Kim K (2020) Diagnostic performance of F-18 FDG PET for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis; a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol 27:2103–2115

Sperry BW, Tamarappoo BK, Oldan JD et al (2018) Prognostic impact of extent, severity, and heterogeneity of abnormalities on 18F-FDG PET scans for suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11:336–345

Flores RJ, Flaherty KR, ** Z, Bokhari S (2020) The prognostic value of quantitating and localizing F-18 FDG uptake in cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol 27:2003–2010

Schwartz RG, Malhotra S (2020) Optimizing cardiac sarcoid imaging with FDG PET: lessons from studies of physiologic regulation of myocardial fuel substrate utilization. J Nucl Cardiol 27:490–493

Slart R, Glaudemans A, Lancellotti P et al (2018) A joint procedural position statement on imaging in cardiac sarcoidosis: from the Cardiovascular and Inflammation & Infection Committees of the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. J Nucl Cardiol 25:298–319

Gormsen LC, Haraldsen A, Kramer S, Dias AH, Kim WY, Borghammer P (2016) A dual tracer 68Ga-DOTANOC PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT pilot study for detection of cardiac sarcoidosis. EJNMMI Res 6:52

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ et al (2015) ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015;36:3075–3128.

Pelletier-Galarneau M, Abikhzer G, Harel F, Dilsizian V (2020) Detection of native and prosthetic valve endocarditis: incremental attributes of functional FDG PET/CT over morphologic imaging. Curr Cardiol Rep 22:93

Bruun NE, Habib G, Thuny F, Sogaard P (2014) Cardiac imaging in infectious endocarditis. Eur Heart J 35:624–632

Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Ajmal S et al (2019) Meta-analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Nucl Cardiol 26:922–935

Gomes A, Glaudemans A, Touw DJ et al (2017) Diagnostic value of imaging in infective endocarditis: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 17:e1–e14

Philip M, Tessonnier L, Mancini J et al (2019) 333018F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography computed tomography (PET/CT) for the diagnosis of prosthetic valve infective endocarditis (PVIE): a prospective multicenter study [abstract]. Eur Heart J 2019;40:ehz745.0082.

de Camargo RA, Sommer Bitencourt M, Meneghetti JC et al (2020) The role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the diagnosis of left-sided endocarditis: native vs prosthetic valves endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 70:583–594

Mahmood M, Abu SO (2020) The role of 18-F FDG PET/CT in imaging of endocarditis and cardiac device infections. Semin Nucl Med 50:319–330

Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA et al (2020) European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace 22:515–549

Vilacosta I, Sarria C, San Roman JA et al (1994) Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography for diagnosis of infected transvenous permanent pacemakers. Circulation 89:2684–2687

Rubini G, Ferrari C, Carretta D et al (2020) Usefulness of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with cardiac implantable electronic device suspected of late infection. J Clin Med 9:2246

Sarrazin JF, Philippon F, Tessier M et al (2012) Usefulness of fluorine-18 positron emission tomography/computed tomography for identification of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. J Am Coll Cardiol 59:1616–1625

Graziosi M, Nanni C, Lorenzini M et al (2014) Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of infective endocarditis in patients with an implanted cardiac device: a prospective study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 41:1617–1623

Ploux S, Riviere A, Amraoui S et al (2011) Positron emission tomography in patients with suspected pacing system infections may play a critical role in difficult cases. Heart Rhythm 8:1478–1481

Mahmood M, Kendi AT, Farid S et al (2019) Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol 26:958–970

Diemberger I, Bonfiglioli R, Martignani C et al (2019) Contribution of PET imaging to mortality risk stratification in candidates to lead extraction for pacemaker or defibrillator infection: a prospective single center study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46:194–205

Kim J, Feller ED, Chen W, Liang Y, Dilsizian V (2019) FDG PET/CT for early detection and localization of left ventricular assist device infection: impact on patient management and outcome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 12:722–729

de Vaugelade C, Mesguich C, Nubret K et al (2019) Infections in patients using ventricular-assist devices: comparison of the diagnostic performance of 18F-FDG PET/CT scan and leucocyte-labeled scintigraphy. J Nucl Cardiol 26:42–55

Okeie K, Shimizu M, Yoshio H et al (2000) Left ventricular systolic dysfunction during exercise and dobutamine stress in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:856–863

Aoyama R, Takano H, Kobayashi Y et al (2017) Evaluation of myocardial glucose metabolism in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. PLoS ONE 12:e0188479

Tzolos E, Andrews JP, Dweck MR (2020) Aortic valve stenosis-multimodality assessment with PET/CT and PET/MRI. Br J Radiol 93:20190688

Gupta K, Dixit P, Ananthasubramaniam K (2021) Cardiac PET in aortic stenosis: potential role in risk refinement? J Nucl Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-021-02714-7

Zhou W, Bajaj N, Gupta A et al (2021) Coronary microvascular dysfunction, left ventricular remodeling, and clinical outcomes in aortic stenosis. J Nucl Cardiol 28:579–588

Dulgheru R, Pibarot P, Sengupta PP et al (2016) Multimodality imaging strategies for the assessment of aortic stenosis: viewpoint of the Heart Valve Clinic International Database (HAVEC) Group. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 9:e004352

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amit Bansal, Karthikeyan Ananthasubramaniam: conceptualization; methodology; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; visualization; investigation. Karthikeyan Ananthasubramaniam: supervision; Amit Bansal, Karthikeyan Ananthasubramaniam, Stephanie Stebens: writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bansal, A., Ananthasubramaniam, K. Cardiovascular positron emission tomography: established and emerging role in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail Rev 28, 387–405 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-022-10270-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-022-10270-6