Abstract

Background

In May 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force issued a grade D recommendation against PSA-based prostate cancer screening. Epidemiologists have concerns that an unintended consequence is a problematic increase in high-risk disease and subsequent prostate cancer-specific mortality.

Materials and methods

To assess the effect of decreased PSA screening on the presentation of high-risk prostate cancer post-radical prostatectomy (RP). Nine high-volume referral centers throughout the United States (n = 19,602) from October 2008 through September 2016 were assessed and absolute number of men presenting with GS ≥ 8, seminal vesicle and lymph node invasion were compared with propensity score matching.

Results

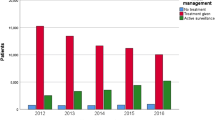

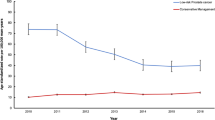

Compared to the 4-year average pre-(Oct. 2008–Sept. 2012) versus post-(Oct. 2012–Sept. 2016) recommendation, a 22.6% reduction in surgical volume and increases in median PSA (5.1–5.8 ng/mL) and mean age (60.8–62.0 years) were observed. The proportion of low-grade GS 3 + 3 cancers decreased significantly (30.2–17.1%) while high-grade GS 8 + cancers increased (8.4–13.5%). There was a 24% increase in absolute numbers of GS 8+ cancers. One-year biochemical recurrence rose from 6.2 to 17.5%. To discern whether increases in high-risk disease were due to referral patterns, propensity score matching was performed. Forest plots of odds ratios adjusted for age and PSA showed significant increases in pathologic stage, grade, and lymph node involvement.

Conclusions

All centers experienced consistent decreases of low-grade disease and absolute increases in intermediate and high-risk cancer. For any given age and PSA, propensity matching demonstrates more aggressive disease in the post-recommendation era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

22 July 2019

In the original publication, part of funding information was missed.

Abbreviations

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- USPSTF:

-

United States Preventive Services Task Force

- GS:

-

Gleason score

- RP:

-

Radical prostatectomy

- SVI:

-

Seminal vesicle invasion

- LNI:

-

Lymph node involvement

- BCR:

-

Biochemical recurrence

- PCSM:

-

Prostate cancer-specific mortality

References

United States Preventive Services Task Force (2008) Screening for prostate cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 149:185–191

Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T et al (2011) Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the US preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med 155:762–771

Lin K, Croswell JM, Koenig H, et al. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer—an evidence updated for the US preventive services task force. Agency for healthcare research and quality. 2011; AHRQ Publication No. 12-05160-EF-1

Catalona WJ, D’Amico AV, Fitzgibbons WF et al (2012) What the US preventive services task force missed in its prostate cancer screening recommendation. Ann Intern Med 157:137–138

Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G et al (2010) Mortality results from Goteborg randomized population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol 11:725–732

Hakama M, Moss SM, Stenman UH, et al. (2017) Design-corrected variation by centre in mortality reduction in the ERSPC randomized prostate cancer screening trial. J Med Screen 24(2):98–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141316652174

Tsodikov A, Gulati R, Heijnsdijk EAM et al (2017) Reconciling the effects of screening on prostate cancer mortality in the ERSPC and PLCO trials. Ann Intern Med 167(7):449–455

Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MK, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guidelines. American Urological Association (AUA). 2013

PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. PDQ prostate cancer screening. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated 11/01/2016

Barocas DA, Mallin K, Graves AJ et al (2016) Effect of the USPSTF grade D recommendation against screening for prostate cancer on incident prostate cancer diagnoses in the United States. J Urol 194:1588–1593

Shoag J, Halpern JA, Lee DJ et al (2016) Decline in prostate cancer screening by primary care physicians: an analysis of trends in the use of digital rectal examination and prostate specific antigen testing. J Urol 196:1–6

Kelly SP, Rosenburg PS, Anderson WF et al (2017) Trends in the incidence of fatal prostate cancer in the United States by race. Eur Urol 71:195–201

Gulati R, Gore JL, Etzioni R (2013) Comparative effectiveness of alternative PSA-based prostate cancer screening strategies. Ann Intern Med 158:145–153

Jemal A, Fedewa SA, Ma J, Siegel R, Lin CC, Brawley O, Ward EM (2015) Prostate cancer incidence and PSA testing patterns in relation to USPSTF screening recommendations. JAMA 314(19):2054–2061. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.14905

Halpern JA, Shoag JE, Mittal S, Oromendia C et al (2016) Prognostic significance of digital rectal examination and prostate specific antigen in the prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening arm. J Urol 197(2):363–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.092

Halpern JA, Shoag JE, Artis AS et al (2017) National trends in prostate biopsy and RP volumes following the US preventive services task force guidelines against prostate-specific antigen screening. JAMA Surg 152(2):192–198. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2016.3987

Eapen RS et al (2017) Impact of the United States Preventive Services Task Force ‘D’ recommendation on prostate cancer screening and staging. Curr Opin Urol 27(3):205–209

Kelly SP, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF, Andreotti G et al (2016) Trends in the incidence of fatal prostate cancer in the United States by race. Eur Urol 71(2):195–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.011

Herget KA, Patel DP, Hanson HA, Sweeney C, Lowrance WT (2016) Recent decline in prostate cancer incidence in the United States, by age, stage, and Gleason score. Cancer Med 5(1):136–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.549

Gulati R, Wever EM, Tsodikov A et al (2011) What if I don’t treat my PSA-detected prostate cancer? Answers from three natural history models. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 20(5):740–750. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0718

Stampfer MJ, Janh JL, Gann PH (2014) Further evidence that prostate-specific antigen screening reduces prostate cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(3):dju026. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju026

Mano R, Eastham J, Yossepowitch O (2016) The very-high-risk prostate cancer: a contemporary update. Prostate Cancer Prostat Dis 19:340–348

Carlsson S, Vickers AJ, Roobol M (2012) Prostate cancer screening: facts, statistics, and interpretation in response to the US preventive services task force review. J Clin Urol 30:2581–2584

Novara G, Ficarra V, Mocellin S et al (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting oncologic outcome after robot-assisted RP. Eur Urol 62:382–404

Hong YM, Hu JC, Paciorek AT et al (2010) Impact of RP positive surgical margins on fear of cancer recurrence: results from CaPSURE. Urol Oncol 28:268–273

Williams SB, Gu X, Lipsitz SR et al (2011) Utilization and expense of adjuvant cancer therapies following RP. Cancer 117:4846–4854

Lowrance WT, Eastham JA, Yee DS et al (2012) Costs of medical care after open or minimally invasive prostate cancer surgery: a population-based analysis. Cancer 118:3079–3086

Liss MA, Lusch A, Morales B (2012) Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: 5-year oncological and biochemical outcomes. J Urol 188(6):2205–2210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.009

Pound CR, Partin AW, Eisenburg MA et al (1999) Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following RP. JAMA 281:1591–1597

Freedland SJ, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA (2005) Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after RP. JAMA 294:433–439

Kwon YS, H YS, Modi PK, et al. (2015) Oncologic outcomes in men with metastasis to the prostatic anterior fat pad lymph node: a multi-institution international study. BMC Urol 15:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-015-0070-1

Tanimoto R, Fashola Y, Scotland KB, et al. (2017) Risk factors for biochemical recurrence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: a single surgeon experience. BMC Urol 35(4):149.e1–149.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2016.10.015

Gulati R, Cheng HH, Lange PH, et al. (2017) Screening men at increased risk for prostate cancer diagnosis: model estimates of benefits and harms. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 26(2):222–227. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0434

Cheng L, Zinke H, Blute ML et al (2011) Risk of prostate carcinoma death in patients with lymph node metastasis. Cancer 91:66–73

Hu JC, Williams SB, Carter SC, et al. (2015) Population-based assessment of prostate specific antigen testing for prostate cancer in the elderly. Urol Oncol 33(2):69.e29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.06.003

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Urology research coordinators, fellows, and students who have contributed to data collection and collation: Erica Huang, Anthony Warner, Omesh Ranasinghe, Bonita Powell, Kellie McWilliams, Mary Achim, Pascal Mouracade (MD), Tadzia Harvey, Brian Shinder (MD). In support of Dr. Edward and Arthur Lui (MD) and in memory of their parents Mr. and Mrs. L.H.M Lui.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahlering, T., Huynh, L.M., Kaler, K.S. et al. Unintended consequences of decreased PSA-based prostate cancer screening. World J Urol 37, 489–496 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2407-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2407-3